Abstract

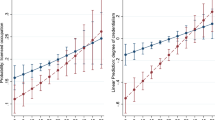

This paper estimates conditional demand models to examine the impact of immigration and different measures of offshoring on the labour demand and demand elasticities of native workers in four different types of occupational groups: managers/professionals, clerical workers, craft (skilled) workers and manual workers. The analysis is conducted for the period 2008–2017 for four economies Austria, Belgium, France and Spain. Our results point to important and occupation-specific direct and indirect effects: both offshoring – particularly services offshoring – and immigration have negative direct employment effects on all occupations, but native clerks and manual workers are affected the most, and native managers/professionals the least. Our results also identify an important elasticity-channel of immigration and offshoring and show that some groups of native workers can also gain from globalisation through an improvement in their wage-bargaining position. Overall, our results indicate a deterioration in the bargaining power of native manual workers arising from both immigration and offshoring and an improvement in the bargaining position of native craft workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

02 June 2022

The layout has been corrected in the original version.

Notes

The interaction term in general can be interpreted as how a percentage increase in the migrant share (of offshoring) affects employment of natives at a given wage rate. Centring refers to setting the variables always in relation to the average values (of wage rates, of migrant shares, of offshoring).

In this rather broad group managers represent the minority, only accounting for between 30% and 40%, on average.

See, for example, Landesmann et al., (2015) for an overview.

All variables stem from either Eurostat or OECD. A variety of labour market programmes were tried, all of them designed to impact labour supply.

This paper was published in a somewhat modified form as Wright (2014).

EU-LFS statistics provides information on country of birth at a relatively aggregate level; however, the advantage of LFS statistics was that we could compile the composition of migrants at the industry level and occupational level.

The population growth figures of migrants and the overall population were obtained from Eurostat population statistics, complemented with data from national sources and the OECD International Migration Database.

The construction of this variable used access to three data bases: WIOD release 2016, plus the upcoming WIOD release available to the authors regarding imported intermediate inputs (at the industry level) and output growth, while hours worked was taken from EU-LFS statistics.

NTMs were taken from a special wiiw database (see wiiw NTM Data) and AVEs from Adarov & Ghodsi (2021).

We did not include Luxembourg, whose migration numbers and patterns are too different from the other ‘old’ EU member states.

A more extensive descriptive analysis is available from the accompanying working paper (Landesmann & Leitner, 2020).

See Table S1 in the online annex for the underlying industry classification.

Results for 2-year and 4-year differences are available in Tables S2 and S3 in the online annex. Following one referee’s suggestion, we also tested for the interrelationship between effects from immigration and the extent to which industries are open to trade in intermediates. We ran estimates with triple interaction terms between wages, our offshoring measures and the migration shares. With regard to industry differentiation, our estimates hardly gave any significant results. Given the lack of statistically significant results, we do not report the results in this paper.

Results for 2-year and 4-year differences are available in Tables S6 and S7 in the online annex. Following one referee’s suggestion, we also tested for the interrelationship between effects from immigration and the extent to which industries are open to trade in intermediates. We ran estimates with triple interaction terms between wages, our offshoring measures and the migration shares. With regard to industry differentiation, our estimates hardly gave any significant results. Given the lack of statistically significant results, we do not report the result tables in this paper.

Specifically, we included interactions between three variables, namely wages, our measure(s) of offshoring and the ‘South’ dummy to capture differences with respect to offshoring and between wages, the migrant share (total and by occupational category) and the ‘South’ dummy to capture differences with respect to migration.

Results for all remaining estimations (i.e. when the total offshoring measure is used or when total offshoring is further differentiated in terms of narrow and broad offshoring) are available from the authors upon request.

Results for the remaining specifications are not reported here but are available from the authors upon request.

6. References

Adarov, A., & Ghodsi, M. (2021). Heterogeneous Effects of Non-tariff Measures on Cross-border Investments: Bilateral Firm-level Analysis. The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw) Working Paper No. 210

Altonji, J. G., & Card, D. (1991). The Effects of Immigration on the Labor Market Outcomes of Less-Skilled Natives. In J. M. Abowd, & R. B. Freeman (Eds.), Immigration, Trade and Labor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Baldwin, R. (2020). The Globotics Upheaval: Globalisation, Robotics and the Future of Work. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Bargain, O.,and, & Peichl, A. (2016). Own-wage labour supply elasticity: Variation across time and estimation methods. IZA Journal of Labour Economics, 5(10), 1–31

Bruno, G. S. F., Falzoni, A. M., & Helg, R. (2004). Measuring the effect of globalization on labour demand elasticity: An empirical application to OECD countries. Working Paper No. 153, CESPRI, Universita Commerciale Luigi Bocconi, Milan

Bruno, G. S. F., Falzoni, A. M., & Helg, R. (2005). Estimating a dynamic labour demand equation using small, unbalanced panels: An application to Italian manufacturing sectors. Milan: Universita Commerciale Luigi Bocconi

Card, D. (2001). Immigrant Inflows, Native Outflows, and the Local Market Impacts of Higher Immigration. Journal of Labor Economics, 19(1), 22–64

Cattaneo, C., Fiori, C. V., & Peri, G. (2015). What happens to the careers of European workers when immigrants ‘take their jobs’? Journal of Human Resources, 50(3), 655–693

Costinot, A., & Vogel, J. (2010). Matching and inequality in the world economy. Journal of Political Economy, 118(4), 747–786

Dustmann, C., Schönberg, U., & Stuhler, J. (2016). The impact of immigration: Why do studies reach such different results? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(4), 31–56

Evers, M., de Mooij, R., & van Vuuren, D. (2008). The wage elasticity of labour supply: A synthesis of empirical estimates. De Economist, 156(1), 25–43

Fajnzylber, P., & Maloney, W. (2005). Labor Demand and Trade Reform in Latin America. Journal of International Economics, 66(2), 423–446

Feenstra, R. C., & Hanson, G. H. (1999). The impact of outsourcing and high-technology capital on wages: Estimates for the United States, 1979–1990. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114, 907–941

Foster-McGregor, N., Poeschl, J., & Stehrer, R. (2016). Offshoring and the elasticity of labour demand. Open Economy Review, 27, 515–540

Grossman, G. M., & Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2008). Trading tasks: A simple theory of offshoring. American Economic Review, 98(5), 1978–1997

Hamermesh, D. (1993). Labour Demand. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Hijzen, A., & Swaim, P. (2010). Offshoring, labour market institutions and the elasticity of labour demand. European Economic Review, 54, 1016–1034

Hoekman, B., & Shepherd, B. (2021). Services Trade Policies and Economic Integration: New Evidence for Developing Countries. World Trade Review, 20, 115–134

Jensen, B., & Kletzer, L. G. (2005). Tradable services: Understanding the scope and impact of services offshoring. Brookings Trade Forum, Brookings Institution Press

Krishna, P., Mitra, D., & Chinoy, S. (2001). Trade liberalization and labor demand elasticities: Evidence from Turkey. Journal of International Economics, 55, 391–409

Landesmann, M., Leitner, S., & Jestl, S. (2015). Migrants and natives in EU labour markets: Mobility and job-skill mismatch patterns. wiiw Research Report No. 403, Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), Vienna

Landesmann, M., & Leitner, S. M. (2018). Immigration and offshoring: Two forces of ‘globalisation’ and their impact on labour markets in Western Europe: 2005–2014. wiiw Working Paper No. 156, Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), Vienna

Landesmann, M., & Leitner, S. M. (2020). Immigration and offshoring: Two forces of Globalisation and their impact on Employment and the Bargaining Power of Occupational Groups. wiiw Working Paper No. 174, Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), Vienna

Longhi, S., Nijkamp, P., & Poot, J. (2010). Joint impacts of immigration on wages and employment: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Geographical Systems, 12(4), 355–387

Monte, F., Redding, S. J., & Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2018). Commuting, migration and local employment elasticities. American Economic Review, 108(12), 3855–3890

Ottaviano, G., & Peri, G. (2012). Rethinking the effects of immigration on wages. Journal of the European Association, 10(1), 152-197

Ottaviano, G., Peri, G., & Wright, G. W. (2013). Immigration, offshoring, and American jobs. American Economic Review, 103, 1925–1959

Ottaviano, G. I. P., Peri, G., & Wright, G. W. (2016). Immigration, trade and productivity in services: Evidence from UK firms. CEP Discussion Paper 1353, London School of Economics, London

Pisani, N., & Ricart, J. E. (2016). Offshoring of Services: A Review of the Literature and Organizing Framework. Management International Review, 56, 385–424

Rodrik, D. (1997). Has Globalization Gone Too Far?. Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics

Ruist, J. (2013). Immigrant-native wage gaps in time series: Complementarities or composition effects? Economics Letters, 119, 154–156

Senses, M. (2010). The effects of offshoring on the elasticity of labor demand. Journal of International Economics, 81, 89–98

Sharpe, J., & Bollinger, C. R. (2020). Who competes with whom? Using occupation characteristics to estimate the impact of immigration on native wages. Labour Economics, 66, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2020.101902

Slaughter, M. J. (2001). International trade and labour-demand elasticities. Journal of International Economics, 54, 27–56

Wright, G. C. (2010). Revisiting the employment impact of offshoring. Davis: Job Market Paper, University of California

Wright, G. C. (2014). Revisiting the employment impact of offshoring. European Economic Review, 66, 63–83

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Landesmann, M., Leitner, S.M. Immigration and Offshoring: two forces of globalisation and their impact on employment and the bargaining power of occupational groups. Rev World Econ 159, 361–397 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-022-00470-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-022-00470-5