Abstract

Blue Carbon Ecosystems (BCEs) help mitigate and adapt to climate change but their integration into policy, such as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), remains underdeveloped. Most BCE conservation requires community engagement, hence community-scale projects must be nested within the implementation of NDCs without compromising livelihoods or social justice. Thirty-three experts, drawn from academia, project development and policy, each developed ten key questions for consideration on how to achieve this. These questions were distilled into ten themes, ranked in order of importance, giving three broad categories of people, policy & finance, and science & technology. Critical considerations for success include the need for genuine participation by communities, inclusive project governance, integration of local work into national policies and practices, sustaining livelihoods and income (for example through the voluntary carbon market and/or national Payment for Ecosystem Services and other types of financial compensation schemes) and simplification of carbon accounting and verification methodologies to lower barriers to entry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The UNFCCC Paris Agreement commits signatories to ‘pursue efforts’ to limit the increase in global average temperature to 1.5 °C. Achieving this requires a rapid decarbonisation of the global economy. However, decarbonisation alone will not be sufficient; IPCC scenarios for limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 °C also require the removal of increasing amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere (IPCC 2013). This will rely in part on nature-based solutions (NbS) to conserve and expand natural carbon sinks, delivering climate change mitigation benefits along with co-benefits to society and biodiversity (IUCN 2020). Due to their efficiency in the capture and storage of carbon (relative to terrestrial ecosystems), mangroves, seagrass and tidal marshes—the so-called Blue Carbon Ecosystems (BCEs)—are amongst the most important habitats for climate change mitigation and adaptation (Macreadie et al. 2019). Hence, protection and restoration of BCEs are increasingly recognised as important forms of NbS for achieving climate policy initiatives at local and global scales (Seddon et al. 2020, 2021). Protection and restoration of BCEs offer potentially high returns on investment; Stuchey et al. (2020) report that mangrove conservation and restoration alone could deliver US$0.2 trillion over a 30-year period, delivering a high benefit–cost ratio of 3:1. One hundred and fifty-one countries around the world contain at least one BCE and 71 contain all three (Blue Carbon Initiative 2019), hence there are compelling arguments and multiple opportunities for nations to incorporate BCEs into climate policy.

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) represent the primary mechanism for meeting the global ambitions of the Paris Agreement. Here, countries commit to nationally appropriate actions to mitigate against and adapt to climate change (Article 4.2 Paris Agreement; UNFCCC 2020). NDCs operate on a ratcheting five-year cycle, with each round of public submissions advancing in ambition relative to the previous round (Article 4.3 Paris Agreement). Hence, in theory, the NDC process offers a flexible and transparent mechanism to accelerate progress towards global climate change goals by allowing countries to focus on sensible national priorities, permitting leading nations to set stretching targets and exposing missed commitments and inadequate goals to public scrutiny.

In the first NDC submissions of 2015, 59 countries included coastal ecosystems in their adaptation responses whilst 28 included them as part of mitigation strategies (Herr and Landis 2016). The NDC Partnership (a global coalition of governments and institutions supporting the implementation of NDCs) had received 60 requests from 17 countries for support for NDC implementation plans related to ‘oceans and coasts’, ahead of the second round of submissions in 2020/21 (NDC Partnership 2019). Of these, 13 countries had already included coastal ecosystems in their previous NDC submissions; however, explicit mention of and concrete targets for BCEs remains limited (NDC Partnership 2019). There is therefore considerable scope for the inclusion, enhancement and conceptualisation of BCEs into many more NDCs, including those in which they are already mentioned. Due to delays caused by the Covid-19 pandemic it is possible that some of these opportunities could be realised in this second round of NDC submissions but will certainly be available during the next phase of 2025.

General guidance on developing NDCs includes the importance of community consultation (e.g. Fransen et al. 2017; NDC Partnership 2020). Some NbS projects, including those involving mangroves, have been criticised for failing to respect the rights and agency of local people and for enforcing ‘fortress conservation’ models of protection (e.g. Beymer-Farris and Bassett 2012). Working in partnership with communities is important for many reasons, but three stand out as especially significant for BCEs. First, environmental justice requires that those most affected by climate change and most vulnerable to its impacts (both short and long-term) are central to responses to mitigate and adapt to those changes. Second, BCEs are typically contiguous with human communities who are heavily dependent upon them, hence are usually best understood as socio-ecological (rather than only biological) systems. Third, the knowledge that local communities have, for example about past distributions and diversity, may be vital for effective conservation and restoration activities. Changes in governance regimes associated with BCEs can disproportionately affect the most vulnerable people for good or ill (Fortnam et al. 2021), and management models that are not consented to and supported by local people are likely to fail and to increase development inequalities (Nunan et al. 2021).

To be just and successful, the NDC consultation process must involve the local communities themselves in the planning and implementation stages. Several opportunities and interventions are possible to allow NDCs to do this (Fig. 1). For example, community participation may feature during implementation of projects, specifically with capacity building, the enhanced transparency framework (which reports on individual efforts of countries) and NDC submissions, which are due every five years. Without community involvement in these areas, it is likely that information for submissions would not be complete.

Blue NbS and the NDC ratchet mechanism with potential points in the NDC cycle for community engagement (adapted from UNFCCC Secretariat in Von Unger et al. 2020)

Here, we identify some of the key issues and challenges that are facing communities, policy makers, managers and other stakeholders when considering how best to use the opportunity presented by NDCs to achieve effective and socially just BCE protection and restoration.

Horizon scan methodology

Horizon scans identify gaps, threats and opportunities which have not been addressed in detail before, with the aim of outlining future priorities in the field (Sutherland and Woodroof 2009; Sutherland et al. 2013; Cook et al. 2014). Through existing networks and a literature search, we identified and contacted 50 experts in the field of blue carbon. Of these, 33 responded, drawn from a wide geographic distribution and range of backgrounds, including academia, conservation, government agencies and project development (including project officers based on site at two ongoing BCE projects). (Fig. 2a and b). We acknowledge that private stakeholders were not included (there was no response from contacting these stakeholders), and results are weighted towards those in research/academia.

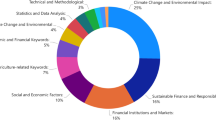

Stakeholders were asked the following: “What are your top ten fundamental questions for the incorporation of carbon (in particular blue carbon) into NDCs at a community-level?”. We received a total of 197 questions (some stakeholders grouped and worked together on question development and some submitted fewer than ten questions), which were sorted qualitatively into main themes by three team members using an iterative approach (following the progressive refinement of qualitative themes as described by Williams and Moser 2019). Each question was categorised independently by one individual into self-defined themes. These categorisations were then sense-checked with the other two team members, with questions moved between themes if required following discussion. Theme titles were then confirmed following discussion, with a final list of ten themes and 111 questions emerging. The initial questions, using verbatim submitted language, were then shared again with all stakeholders using survey software (Survey Hero- available from surveyhero.com), grouped within the emergent themes; stakeholders were asked to rank these questions in importance for the successful incorporation of BCEs into NDCs with full engagement of local communities. The top ranked question under each theme then formed the overarching research question reported here. Stakeholders were then allocated themes according to their specific areas of expertise, with the remit of endorsing, editing or re-writing preliminary draft text written by the core team. Stakeholders were provided a list of all questions for each theme. For a list of all questions see Appendix S1.

Results

The ten emergent themes fell into the three broad areas of (1) people, (2) policy and finance and (3) science and technology (Fig. 3).

People

Theme 1: Environmental and social sustainability

How do we safeguard the sustainability of local livelihoods when implementing and operating BC projects?

To ensure long-term support from communities for the conservation of BCEs, livelihoods must be sustained, and alternative income generation (AIG) created, where unsustainable use of BCEs threaten their conservation e.g. excessive logging of mangroves for firewood and timber (e.g. Badola et al 2012). Using carbon credits for blue carbon offsetting has been successful in supporting community development projects such as Vanga Blue Forest in Kenya (ACES 2021). Here, the opportunity costs of forest protection (foregoing mostly illegal and small-scale cutting) are outweighed by carbon income, with the individuals most affected (such as cutters) compensated through new opportunities (for example to act as forest scouts). Co-management rights to the forest under national legislation and strong collaboration between the community, the government, NGOs and research institutions have been key to the sustainability of this project; successful BCE projects will typically need good multi-stakeholder collaboration (Fig. 4).

Stakeholders in blue carbon activities, with communities at the heart of the process. Adapted from Vanderklift et al. (2019)

Using Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES—for example the sale of carbon credits) is one approach to help with long-term project funding and to compensate for conservation impacts on livelihoods (Van Hecken et al. 2015; Shapiro-Garza et al. 2020). Demand is growing; trading on the voluntary market increased by 6% between 2018 and 2019, with particularly strong demand for credits related to NbS, which saw a 30% increase in price (Forest Trends’ Ecosystem Marketplace 2020). Interventions that improve gender equity and biodiversity conservation together with mitigation actions are becoming more attractive than projects with a single purpose (Herr et al. 2015) and new forms of crediting that recognise these broader aims, such as Sustainable Development Goal credits, are emerging (Verra 2020). However, all such funding, dependent as it is on global relationships between polluters (or ‘funders’), local stewards and ecosystems, must be regarded as inherently uncertain; it is incumbent, therefore, on project teams to look for ways in which funding can help establish or reinforce less fragile sources of livelihoods and also secure alternative long-term financial sustainability mechanisms.

Theme 2: Participation and collaboration

How do we promote greater participation of local communities in blue carbon projects, when their most pressing needs are related to immediate livelihoods and infrastructure?

Local perceptions of project legitimacy, derived at least in part from participation, are widely acknowledged to be critical to sustained success in community-based conservation, particularly in PES (Wunder et al. 2018; Wells et al 2020). Frameworks for just and sustainable community engagement with BCE projects are emerging (e.g. The Commonwealth Blue Charter 2021) and include the Code of Conduct for Blue Carbon (Bennett et al. 2017; Blue Carbon Code of Conduct), developed by 96 stakeholder institutions and individuals. This represents an explicit acknowledgement of the importance of community rights and participation and shows a unity of purpose amongst the Blue Carbon community in learning from mistakes made in terrestrial ecosystems. Whilst arguments for community participation are just as strong in terrestrial as in BCE projects, the latter differ in emerging later and hence benefiting from other’s experience. Hence, the intention is clear, but achieving it requires patience, skill and funding.

Multiple approaches can be used to create socially inclusive and participatory governance; of special relevance to BCEs is the creation of networks of locally managed marine areas (LMMAs), or responsible fishing areas, involving local people in community monitoring and compliance. These can provide protection for the long-term storage of Blue Carbon and buy-in from local communities (Vierros 2017; Moraes 2019). Local education campaigns may also be particularly important for BCEs since their benefits (particularly those associated with ‘hidden’ habitats such as subtidal seagrass) may be less obvious to people than those from terrestrial forests. Whilst direct financial or livelihood benefits are likely to be an important predictor of the long-term success of BCE community projects, evidence from terrestrial PES shows that non-financial incentives, including a sense of community pride and ownership, can also be highly influential (Pascual et al 2014). However, participation of the most marginalised people in governance processes is likely to need explicit recognition and financial support, as part of a procedural justice approach (Theme 3).

Theme 3: Governance of local projects

How can we distribute benefits from blue carbon projects within communities in a manner that benefits the most vulnerable and marginalised members and avoids elite capture?

In general, BCE projects that are perceived to have local legitimacy and that build on and respect de facto governance models are more likely to succeed (Nunan et al. 2021). However, this on its own does not ensure such projects will enhance equity; for example, existing inequalities may be perpetuated and upheld if they are rooted in cultural norms, resulting in elite capture of benefits by those with the most resources and power (Staddon et al. 2015). Implementation of the NDCs should go beyond recognition of local agency to include explicit social justice aims; for example, the NDC Partnership has created a strategy which aims to integrate gender equality into national plans (NDC Partnership 2019). Hence, an explicit commitment to procedural justice, defined as the concept of fair social processes and procedures in decision-making (Tyler and Lind 2002), is needed to help achieve these broader aims of inclusion. Wood et al. (2018) propose a useful six-step approach to manage power in Community-Based Climate Change Development projects (CB-CCD), which involves explicit attempts to avoid domination by one or more powerful groups and ways to ensure the vulnerable are empowered and can voice grievances (Table 1).

Procedural justice considerations may be especially relevant to BCEs. These environments often experience contested or absent tenure and overlapping jurisdictions between sectors such as forestry and fisheries. Around half of the small-scale fishers that rely on them are women, and fishing communities are often marginalised and poor, with seasonal flows of migrant workers and conflict between small and large scale sectors (FAO 2018). These factors will increase the chances of disadvantaging already marginalised groups during stakeholder conversations if procedural justice questions are not made explicit.

Theme 4: Land rights and tenure

What tenure and land rights do we need to ensure local communities have ownership of blue carbon ecosystems?

Inadequate or insecure tenure and property rights are recognised as a longstanding barrier to community-based natural resource management (USAID 2006; Lockie 2013), especially for blue carbon programmes (Hejnowicz et al. 2015; Beeston et al. 2020; Bryan et al. 2020). The allocation of tenure or property rights is often complicated on the coast, where ecosystems are typically common pool resources governed under different and overlapping sectors (Vanderklift et al. 2019). For example, responsibility for mangrove management is frequently shared across government ministries, often with conflicting mandates (e.g. Friess et al. 2016; Banjade et al. 2017). This complicated picture is likely to worsen as boundaries begin to shift landward through sea level rise (Sefrioui 2017). Furthermore, traditional customary (de facto) rights frequently coexist with formal de jure rights, particularly in Africa and the Pacific. Collectively, this results in a complex patchwork of property right regimes (e.g. public, private, common and open access), and institutional and legal mandates (USAID 2006; Olander and Ebeling 2011; Chimhowu 2019).

Some countries are now working towards including mangroves in forest definitions to be incorporated in NDC submissions. This may help resolve tenureship conflicts. An example comes from Tahiry Honko in Madagascar, in which conservation of 1200 ha of mangrove is supported by linking mangrove protection with the national REDD + strategy and selling carbon credits on the voluntary market (Rakotomahazo et al. 2019). In other cases, ownership rights to resources (such as the trees or the carbon they contain) rather than to land can be a route through tenureship barriers. A clear right to carbon is a requirement of accreditation in the voluntary carbon market (Bell-James 2016); many countries now have legislation that can, in principle, permit community tenureship of blue carbon (for example, the Tanzanian Forest Act (2002) and the Kenya Forest Act (2005)).

Formalising rights, however, does not guarantee fair outcomes for local communities. Experience with REDD + has shown that changes in carbon rights can lead to land grabbing and the exclusion of traditional landowners (Bryan et al. 2020). Hence, processes of formalisation should be founded on principles of deliberation, community partnership and co-production, and should avoid entrenching historical inequalities and setting-up new ones, whilst recognising customary (and historical) rights to resources (Rotich et al. 2016).

Theme 5: Communication and dissemination

How do we scale up local efforts and make it easier for communities to conserve and enhance blue carbon?

Local BCE projects may not make substantial contributions at the national scale. Scaling such projects and developing programmatic rather than project-based interventions will often be needed to make substantial contributions to mitigation and adaptation goals. Barriers to achieving this include policy, financial and technical challenges (Macreadie et al. 2019).

For instance, it has been recently highlighted that Small Island Developing States (SIDS) require greater multilateral collaboration to speed up national BCE assessments (Delgado-Gallego et al. 2020). Similarly, whilst Kenya’s NDC now has an explicit commitment to ‘conduct blue carbon readiness assessment for full integration of blue carbon/ocean carbon into NDCs’ (Tobiko et al. 2020), 70% of the estimated budget needed to achieve this must come from international sources. A tension exists between the importance, emphasised in themes 1–3, of careful, inclusive, and site-specific work with communities and the imperatives of enhancing impact at national and international levels. Resolving this requires proper investment in community engagement across thousands of sites, combined with more streamlined incorporation of these site-specific initiatives into national and international frameworks; traditional agricultural extension and outreach services, provided for decades in many countries, give multiple examples of how local changes can bring national results (FAO). Another example of direct relevance comes from the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, which has operated since 2008 to help build national capacity for REDD + and has strong representation of indigenous people and civil society in its governance. Combining the science of NbS with collective action by bodies supporting initiatives such as the Global Mangrove Alliance, the Blue Carbon Initiative, the Nature4Climate and the Bonn Challenge can help to scale up local efforts for the inclusion of BCEs into upcoming NDCs, which increase in ambition with each submission (UNFCCC 2018).

Policy and finance

Theme 6: Policy interactions

To what extent can blue carbon projects help meet NDCs for each nation?

If a country’s previous NDC has not referenced blue carbon, integration of blue carbon into the NDC should begin by checking any current relevant policies, followed by an assessment of the mitigation/adaptation potential of these nd how they can be promoted (Durham 2020). Box 1 provides an example of how Kenya has been supported in blue carbon inclusion for their NDCs.

Science and technology

Theme 9: Ecosystem-based management

What are the knowledge gaps that hinder the inclusion of all blue carbon ecosystems in NDCs?

Data on the extent and dynamics of BCEs are often lacking, with large variations between nations in the quality of information. In recent years, significant progress has been made to increase knowledge on the carbon storage and sequestration potential of mangroves; seagrass and tidal marsh carbon storage and sequestration are less well understood, and this contributes in part to their current absence from carbon trading (Hejnowicz et al. 2015; Shilland et al. 2021).

There are nine BCE projects currently registered with the VCM (under Plan Vivo—two Kenyan and one Malagasy; under VCS—in China, Myanmar, Senegal, India and Indonesia; under Gold Standard—in India). All are based on mangrove conservation and restoration, with no examples of saltmarsh or seagrass meadow carbon trading projects. This limited uptake of carbon financing as a mechanism for blue carbon management is due, in part, to data gaps that hinder carbon calculations and present a barrier to certification (Wylie et al 2016; Shilland et al 2021). Similar problems apply to inclusion of BCEs within NDCs with many governments unaware or uncertain about the extent of their Blue Carbon resources and the options available to restore or protect them. This can be solved through strengthening of national blue carbon monitoring initiatives, without considerable increase in funding requirements, by linking them to national forest monitoring and REDD + MRV actions.

Of the three BCEs, seagrass meadows are both the most extensive and the most poorly understood. Scientific uncertainties limiting policy progress include i) the provenance of allochthonous carbon (produced outside of the seagrass ecosystem) and whether this can be claimed as carbon benefits by projects focussed on seagrass; ii) rates of carbon loss from seagrass sediment following damage or destruction, or rates of carbon accumulation following restoration or protection; and iii) the relevance of calcification in seagrass ecosystems, and of accumulation of inorganic carbon particularly carbonates, in calculating net carbon fluxes (see UNEP 2020a for an expansion of these scientific challenges). In addition, the total area and recent trends in coverage of both seagrass and salt marsh remain poorly known in many countries and regions. Whilst new developments in remote sensing are rapidly improving understanding of total coverage (see e.g. Mcowen et al. 2017), the other uncertainties will probably remain obstacles for policy at least in the near future. If salt marsh and seagrass are to be routinely incorporated into the next round of NDCs their roles in adaptation, as well as their contributions to other ecosystem services, need to be recognised; a narrow focus on carbon may continue to exclude them. Conservative assumptions on sequestration along with flexibility in crediting (for example by recognising additional outcomes such as contributions to SDGs) should allow inclusion of seagrass and saltmarsh into both VCM standards and NDC processes (Shilland et al. 2021).

Theme 10: Technology and methods

How do we simplify carbon accounting and validation methodologies so that they can be employed or contributed to by communities?

The IPCC Wetland Supplement (IPCC 2013) reports methodologies for mangrove, saltmarsh and seagrass management using three tiers. Tier 1 provides default emission factors for all relevant management activities, which can be used if nationally relevant emission factors are unavailable. Adopting Tier 1 emission factors provides the simplest route for community engagement with NDCs. For mangrove and saltmarsh management activities, including restoration, this requires monitoring changes in cover (area) and above-ground biomass and subsequently applying a number of default allometric equations. Determining large-scale changes in biomass of mangroves requires access to satellite or UAV (‘unmanned aerial vehicle’ or drone) imagery (e.g. Sanderman et al. 2018; Navarro et al. 2020), or can be done using field measurements on a smaller scale (Kauffman and Donato 2012). Provided training and support are available, such approaches are well suited to community engagement (Danielsen et al. 2011). Simplified methodologies not only streamlines monitoring, making it more coft-effective, but improves the accessibility of community engagement with the project, increasing equity and perceived legitimacy (Wells et al. 2017). Where there is the institutional support to identify relevant sites, provide training and ensure data analysis and reporting, activities for reversing mangrove forest removal and degradation or facilitating restoration provide a good opportunity for community engagement and one in which technical challenges are not the main barrier.

Only methodologies for the management activities of extraction and restoration are available for seagrass meadows (IPCC 2013). Seagrass restoration can be achieved by active replanting or reseeding, with the former practice being more expensive and requiring skilled direction. The major threat to seagrass meadows is from eutrophication and/or increased turbidity (Orth et al. 2006), often driven by changes in river catchments or coastal developments. As yet, not enough data are available to provide a methodology to account for the effect of these offsite activities. There has been an acceleration of research on BCE since the development of the 2013 IPCC Wetland Supplement and there is scope for new methodologies to be developed for other management activities that impact on seagrass meadows (Oreska et al. 2020).

Community engagement with Blue Carbon projects distinct from NDCs (such as validated VCM projects) present similar technical challenges, some of which are discussed in themes 8 and 9. As noted there, an explicit focus on benefits in addition to carbon may open up flexibility in the accreditation of projects under VCM standards. Standards that currently support BCE projects include the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) and Plan Vivo. The former has approved a specified methodology, VM0033 (Verra 2019), which includes methods to assess abatement with restoration of mangroves, saltmarsh and seagrass meadows (Needleman et al. 2018). This methodology is generally at least as technically demanding—and in some cases much more demanding—than IPCC reporting requirements. Plan Vivo has incorporated mangrove projects using a case-by-case approach with Tier 1 assumptions permitted when deemed appropriate by their Technical Advisory Committee.

Whether the accounting of carbon benefits involves smaller local projects or is a combination of national and local scales, it is likely to remain a complex process involving multiple stakeholders and institutions. Some of this complexity may derive from the scientific processes needed for measuring carbon, but also from the needs to identify sites, demonstrate additionality and establish robust reporting. New risk measuring tools such as CORVI (Climate and Ocean Risk Vulnerability Index) and the IUCN Restoration Opportunities Assessment Methodology ROAM (IUCN 2021) may aid in the prioritisation and rapid assessment of coastal landscapes for blue carbon conservation. Whilst the development of new models, sensors, remote sensing techniques and computation tools to track blue carbon abatement may help streamline site identification and monitoring (Sani et al 2018; Navarro et al 2020), these approaches will require specialist skills and training.

In conclusion, barriers to community engagement arising from the technical and scientific challenges of carbon accounting may be lowered in some areas, through increased flexibility, robust models and consideration of broader outcomes in VCM routes to accreditation. However, the complexity inherent in the broader process remains a barrier for communities in many nations. Communities will continue to need supportive partnerships with government, NGOs and other sectors to be fully engaged.

Synthesis and ways forward

Robust science shows that BCEs have exceptional value, not only for carbon but for a wide range of services. Inspirational projects demonstrate how coastal ecosystems can be conserved and restored for the benefits of nature and people. Growing international momentum promises ways of accelerating the conservation and restoration of BCEs, using climate change policy and other drivers. Realising this promise will require a collective effort to address the questions articulated here; we suggest three broad responses are needed, falling into our categories of people, science and technology and policy and funding. Paying proper attention to matters of inclusion and justice requires genuine commitment to understanding local contexts and to developing trust (Dencer-Brown et al. 2021). Project developers (and the standards and frameworks that support them) need to focus on this, even if it means sacrificing some scientific precision or accountability to markets. Hence, where the science is robust enough to justify Tier 1 approaches, combined with simple conservative assumptions (as is the case in many mangrove systems), a lack of precision should not be used to hinder accreditation of projects or rejection of BCEs from national policy. Research attention needs to be focussed on those areas—such as extent and trends of seagrass and saltmarsh and drivers of total carbon stocks in these habitats—which remain genuine barriers to conservative inclusion of some BCEs into local projects and national plans. On policy and funding, national approaches should invest in community support and retain the flexibility necessary to incorporate existing local projects with a range of funding from private, public and multilateral sources. BCEs are locally unique, resilient, adaptable and defy simple categorisations; our approaches to conserve them should be the same.

References

Association for Coastal Ecosystem Services. 2021. Mikoko Pamoja Project. https://www.aces-org.co.uk/mikoko-pamoja-project/. Accessed 12 May 2021

Badola, R., S. Barthwal, and S.A. Hussain. 2012. Attitudes of local communities towards conservation of mangrove forests: A case study from the east coast of India. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 96: 188–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2011.11.016.

Banjade, M.R., N. Liswanti, T. Herawati, and E. Mwangi. 2017. Governing mangroves: Unique challenges for managing Indonesia’s coastal forests. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR; Washington, DC: USAID Tenure and Global Climate Change Program (Report)

Barnaud, C., and A. Van Paassen. 2013. Equity, power games, and legitimacy: Dilemmas of participatory natural resource management. Ecology and Society 18: 21. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05459-180221.

Beeston, M., L. Cuyvers, and J. Vermilye. 2020. Blue carbon: Mind the gap. Gallifrey Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland (Report)

Bell-James, J. 2016. Developing a framework for ‘blue carbon’ in Australia: Legal and policy considerations. UNSW Law Journal 39: 1583–1611.

Bennett, N.J., L. The, Y. Ota, P. Christie, A. Ayers, J.C. Day, P. Franks, D. Gill, et al. 2017. An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation. Marine Policy 81: 411–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.03.035.

Beymer-Farris, B.A., and T.J. Bassett. 2012. The REDD menace: Resurgent protectionism in Tanzania’s mangrove forests. Global Environmental Change 22: 332–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.11.006.

Blue Carbon Initiative. 2019. Guidelines for Blue Carbon and Nationally Determined Contributions. https://www.thebluecarboninitiative.org/policy-guidance. Accessed 5 May 2020

Bryan, T., J. Virdin, T. Vegh, C.Y. Kot, J. Cleary, and P. Halpin. 2020. Blue carbon conservation in West Africa: A first assessment of feasibility. Journal of Coastal Conservation. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-019-00722-x.

Chimhowu, A. 2019. The ‘new’ African customary land tenure. Characteristics, features and policy implications of a new paradigm. Land Use Policy 81: 897–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.04.014.

Cohen, R., J. Kaino, J.A. Okello, J.O. Bosire, J.G. Kairo, M. Huxham, and M. Mencuccini. 2013. Propagating uncertainty to estimates of above-ground biomass for Kenyan mangroves: A scaling procedure from tree to landscape level. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 968–982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2013.09.047.

Cook, C.N., S. Inayatullah, M.A. Burgman, W.J. Sutherland, and B.A. Wintle. 2014. Strategic foresight: How planning for the unpredictable can improve environmental decision-making. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 29: 531–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.07.005.

Danielsen, F., M. Skutsch, N.D. Burgess, P.M. Jensen, H. Andrianandrasana, B. Karky, R. Lewis, J.C. Lovett, et al. 2011. At the heart of REDD+: A role for local people in monitoring forests? Conservation Letters 4: 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2010.00159.x.

Delgado-Gallego, J, O. Manglani, and C. Sayers. 2020. Cornell university global climate change science and policy course project with Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University and Conservation International December 15. https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/blogs.cornell.edu/dist/1/7755/files/2020/12/AOSIS_CI-Policy-Report-Blue-Carbon_Final.pdf. Accessed 03 May 2021

Dencer-Brown, A.M., R.M. Jarvis, A.C. Alfaro, and S. Milne. 2021. Coastal complexity and mangrove management: An innovative mixed methods research design to address a creeping problem. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/15586898211014422.

Durham, C., T. Thomas and M. Unger. 2020. Inspired by Nature-based Solutions in Nationally Determined Contributions: Synthesis and recommendations for enhancing climate ambition and action by 2020. Gland, Switzerland. Oxford, UK: IUCN and University of Oxford

FAO.org 2018. http://www.fao.org/3/i8347en/I8347EN.pdf. Accessed 3 March 2021

Foresthints. 2021. Indonesian ministry cancels self-declared carbon projects to avoid illegalities. https://foresthints.news/indonesian-ministry-cancels-self-declared-carbon-projects-to-avoid-illegalities/. Accessed 10 September 2021

Forest Trends’ Ecosystem Marketplace, Voluntary Carbon and the Post-Pandemic Recovery. State of Voluntary Carbon Markets Report, Special Climate Week NYC. 2020. Installment. Washington DC: Forest Trends Association, 21 September 2020. https://www.forest-trends.org/publications/state-of-voluntary-carbon-markets-2020-voluntary-carbon-and-the-post-pandemic-recovery/. Accessed 5 May 2021

Fortnam, M., M. Atkins, K. Brown, T. Chaigneau, A. Frouws, K. Gwaro, M. Huxham, J. Kairo, et al. 2021. Multiple impact pathways of the 2015–2016 El Niño in coastal Kenya. Ambio 50: 174–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-020-01321-z.

Fransen, T., E. Northrop, K. Mogelgaard, K. Levin. 2017. Enhancing NDCs by 2020: Achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement. https://files.wri.org/s3fs-public/enhancing-ndcs_0.pdf. Accessed 8 May 2021

Friess, D.A., B.S. Thompson, B. Brown, A.A. Amir, C. Cameron, H.J. Koldewey, S.D. Sasmito, and F. Sidik. 2016. Policy challenges and approaches for the conservation of mangrove forests in Southeast Asia. Conservation Biology 30: 933–949. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12784.

Gress, S.K., M. Huxham, J.G. Kairo, L.M. Mugi, and R. Briers. 2017. Evaluating, predicting and mapping belowground carbon stores in Kenyan mangroves. Global Change Biology 23: 224–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13438.

Harcourt, W., R.A. Briers, and M. Huxham. 2018. The thin(ning) green line? Investigating Changes in Kenya’s Seagrass Coverage. Biology Letters. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2018.0227.

Hejnowicz, A.P., H. Kennedy, M.A. Rudd, and M.R. Huxham. 2015. Harnessing the climate mitigation, conservation, and poverty alleviation potential of seagrasses: prospects for developing blue carbon initiatives and payment for ecosystem service programmes. Frontiers in Marine Science. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2015.00032.

Herr, D., T. Agardy, D. Benzaken, F. Hicks, J. Howard, E. Landis, A. Soles and T. Vegh. 2015. Coastal “blue” carbon. A revised guide to supporting coastal wetland programs and projects using climate finance and other financial mechanisms. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. https://nicholasinstitute.duke.edu/content/coastal-blue-carbon-revised-guide-supporting-coastal-wetland-programs-and-projects-using. Accessed 10 June 2020

Herr, D. and E. Landis. 2016. Coastal blue carbon ecosystems. Opportunities for Nationally Determined Contributions. Policy Brief. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN and Washington, DC: TNC. https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/Rep-2016-026-En.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2020

Hickey, S., and G. Mohan. 2005. Relocating participation within a radical politics of development. Development and Change 36: 237–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-155X.2005.00410.x.

Huff, A. 2021. Frictitious commodities: Virtuality, virtue and value in the carbon economy of repair. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486211015056.

IPCC. 2013. Supplement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories: Wetlands, ed. T. Hiraishi, T. Krug, K. Tanabe, N. Srivastava, J. Baasansuren, M. Fukuda, and T.G. Troxler. IPCC, Switzerland. https://www.ipcc.ch/publication/2013-supplement-to-the-2006-ipcc-guidelines-for-national-greenhouse-gas-inventories-wetlands/. Accessed 5 August 2020

IUCN.org. 2021. Restoration opportunities assessment methodology. https://www.iucn.org/theme/forests/our-work/forest-landscape-restoration/restoration-opportunities-assessment-methodology-roam. Accessed 14 May 2021

IUCN. 2020. Nature-based solutions. https://www.iucn.org/theme/climate-change/resources/key-publications/strengthening-nature-based-solutions-national-climate-commitments. Accessed 5 May 2021

Kauffman, J.B., and D.C. Donato. 2012. Protocols for the measurement, monitoring and reporting of structure, biomass and carbon stocks in mangrove forests. Working Paper 86. CIFOR, Bogor, Indonesia. https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/WPapers/WP86CIFOR.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2021

Kirui, K.B., J.G. Kairo, J. Bosire, K.M. Viergever, S. Rudra, M. Huxham, and R.A. Briers. 2013. Mapping of mangrove forest land cover change along the Kenya coastline using Landsat imagery. Ocean and Coastal Management 83: 19–24.

Lockie, S. 2013. Market instruments, ecosystem services, and property rights: Assumptions and conditions for sustained social and ecological benefits. Land Use Policy 31: 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.08.010.

Macreadie, P.I., A. Anton, J.A. Raven, N. Beaumont, R.M. Connolly, D.A. Friess, J.J. Kelleway, H. Kennedy, et al. 2019. The future of blue carbon science. Nature Communications 10: 3998. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11693-w.

Mcowen, C., L. Weatherdon, J. Bochove, E. Sullivan, S. Blyth, C. Zockler, D. Stanwell-Smith, N. Kingston, C. Martin, M. Spalding, and S. Fletcher. 2017. A global map of saltmarshes. Biodiversity Data Journal 5: e11764. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.5.e11764.

Moraes, O. 2019. Blue carbon in area-based coastal and marine management schemes – a review. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 15: 193–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2019.1608672.

Navarro, A., M. Young, B. Allan, P. Carnell, P. Macreadie, and D. Ierodiaconou. 2020. The application of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) to estimate above-ground biomass of mangrove ecosystems. Remote Sensing of Environment 242: 111747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2020.111747.

NDC Partnership. 2019. https://ndcpartnership.org/news/understanding-blue-carbon-requests-ndc-partnership. Accessed 19 May 2020

NDC Partnership. 2020. Partnership in Action 2020. https://ndcpartnership.org/partnership-action-pia-2020-report. Accessed 25 May 2020

Nunan, F., M. Menton, C.L. McDermott, M. Huxham, and K. Schreckenberg. 2021. How does governance mediate links between ecosystem services and poverty alleviation? Results from a systematic mapping and thematic synthesis of literature. World Development. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105595.

Olander, J., & Ebeling, J. 2011. Building forest carbon projects: Step-by-step overview and guide. In Building forest carbon projects, ed. Johannes Ebeling and Jacob Olander. Forest Trends, Washington, DC. https://www.forest-trends.org/wp-content/uploads/imported/building-forest-carbon-projects_step-by-step_final_7-8-11-pdf.pdf. Accessed 30 July 2020

Oreska, M.P., K.J. McGlathery, L.R. Aoki, A.C. Berger, P. Berg, and L. Mullins. 2020. The greenhouse gas offset potential from seagrass restoration. Scientific Reports 10: 1–15.

Orth, R.J., J.B.T. Carruthers, W.C. Dennison, C.M. Duarte, J.W. Fourqurean, K.L. Heck, A. Randall Hughes, et al. 2006. A global crisis for seagrass ecosystems. BioScience 56: 987–996. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[987:AGCFSE]2.0.CO;2.

Pascual, U., J. Phelps, E. Garmendia, K. Brown, E. Corbera, A. Martin, E. Gomez-Baggethun, and R. Muradian. 2014. Social equity matters in payments for ecosystem services. BioScience 64: 1027–1036. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biu146.

Rakotomahazo, C., L.A. Ravaoarinorotsihoarana, D. Randrianandrasaziky, L. Glass, C. Gough, G.G.B. Todinanahary, and C.J. Gardner. 2019. Participatory planning of a community-based payments for ecosystem services initiative in Madagascar’s mangroves. Ocean & Coastal Management 175: 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.03.014.

Rotich, B., E. Mwangi, and S. Lawry. 2016. Where land meets the sea: A global review of the governance and tenure dimensions of coastal mangrove forests. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR; Washington, DC: USAID Tenure and Global Climate Change Program. https://www.cifor.org/knowledge/publication/6377. Accessed 5 Feb 2021

Sanderman, J., T. Hengl, G. Fiske, K. Solvik, M.F. Adame, L. Benson, J.J. Bukoski, P. Carnell, et al. 2018. A global map of mangrove forest soil carbon at 30 m spatial resolution. Environmental Research Letters 13: 055002.

Sani, D.A., M. Hashim, and M.S. Hossain. 2018. Recent advancement on estimation of blue carbon biomass using satellite-based approach. International Journal of Remote Sensing 40: 7679–7715. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2019.1601289.

Seddon, N., A. Chausson, P. Berry, C.A.J. Girardin, A. Smith, and B. Turner. 2020. Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of Biology. 375: 20190120. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0120.

Seddon, N., A. Smith, P. Smith, I. Key, A. Chausson, C. Girardin, J. House, S. Srivastava, and B. Turner. 2021. Getting the message right on nature-based solutions to climate change. Global Change Biology 27: 1518–1546. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15513.

Sefrioui, S. 2017. Adapting to sea level rise: A law of the sea perspective. In The future of the law of the sea, ed. Andreone G. Cham: Springer, pp. 3–22. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-319-51274-7_1.pdf. Accessed 10 October 2020

Shapiro-Garza, E., P. McElwee, G. Van Hecken, and E. Corbera. 2020. Beyond market logics: Payments for ecosystem services as alternative development practices in the global south. Development and Change 51: 3–25.

Shilland, R., G. Grimsditch, M. Ahmed, S. Banderia, H. Kennedy, M. Potouroglou, and M. Huxham. 2021. A question of standards: Adapting carbon and other PES markets to work for community seagrass conservation. Marine Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104574.

Staddon, S., A. Nightingale, and S. Shrestha. 2015. Exploring participation in ecological monitoring in Nepal's community forests. Environmental Conservation 42: 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1017/S037689291500003X.

Stuchtey, M., A. Vincent, A. Merkl, and M. Bucher. 2020. Ocean solutions that benefit people, nature and the economy. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. https://www.oceanpanel.org/ocean-action/files/ocean-report-short-summary-eng.pdf. Accessed 5 June 2021

Sutherland, W.J., and H.J. Woodroof. 2009. The need for environmental horizon scanning. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 24: 523–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.04.008.

Sutherland, W.J., R.P. Freckleton, H. Charles, J. Godfray, S.R. Beissinger, T. Benton, D.D. Cameron, Y. Carmel, et al. 2013. Identification of 100 fundamental ecological questions. Journal of Ecology 101: 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12025.

The Commonwealth Blue Charter. 2021. Community-led Mangrove conservation in Gazi Bay, Kenya: Lessons from Early Blue Carbon Projects (on-going). https://bluecharter.thecommonwealth.org/community-led-mangrove-restoration-and-conservation-in-gazi-bay-kenya-lessons-from-early-blue-carbon-projects-on-going/. Accessed 8 July 2021

Tobiko, K., A.R. Omamo, P.K Kariuki, and U. Yattani. 2020. Submission of Kenya’s updated nationally determined contribution. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/ndcstaging/PublishedDocuments/Kenya%20First/Kenya%27s%20First%20%20NDC%20(updated%20version).pdf. Accessed 13 June 2021

Tyler, T.R., and E. Allan Lind. 2002. Procedural Justice. In Handbook of Justice Research in Law, ed. J. Sanders and V.L. Hamilton. Boston, MA: Springer.

UNFCCC. 2018. Joint submission to the Talanoa Dialogue. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/78_TNC-CI-IUCN-NWF-FT-BV-CCR-WCS_Talanoa%20Dialogue%20Input%202018.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2020

UNFCCC, 2020. NDC Contributions. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs. Accessed 8 Dec 2020

United Nations Environment Programme. 2020a. Out of the blue: The value of seagrasses to the environment and to people. UNEP, Nairobi, Kenya. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/out-blue-value-seagrasses-environment-and-people. Accessed 5 Feb 2021

United Nations Environment Programme. 2020b. Opportunities and Challenges for Community-Based Seagrass Conservation. UNEP, Nairobi, Kenya. https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/33638/OCCSC.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 6 Feb 2021

USAID. 2006. The role of property rights in natural resource management, good governance and empowerment of the rural poor. United States Agency for International Development: Burlington, Vermont, USA. https://www.land-links.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/USAID_Land_Tenure_Property_Rights_and_NRM_Report.pdf. Accessed 10 June 2021

Vanderklift, M.A., R. Marcos- Martinez, J.R.A. Butler, M. Coleman, A. Lawrence, H. Prislan, A.D. Steven, and L. and Thomas, S. 2019. Constraints and opportunities for market-based and protection of blue carbon ecosystems. Marine Policy 107: 103429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.02.001.

Van Hecken, G., J. Bastiaensen, and C. Windey. 2015. Towards a power-sensitive and socially-informed analysis of payments for ecosystem services (PES): Addressing the gaps in the current debate. Ecological Economics 120: 117–125.

Verra. 2019. Verified Standard Draft. https://verra.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/VCS_Standard_v4.0_DRAFT_11APR2019.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2021

Verra, 2020. Sustainable development verified impact standard. https://verra.org/project/sd-vista/. Accessed 2 June 2021

Vierros, M. 2017. Communities and blue carbon: The role of traditional management systems in providing benefits for carbon storage, biodiversity conservation and livelihoods. Climatic Change 140: 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0920-3.

Von Unger, M., H. Dorothée, S. Thilanka, and S. Castillo. 2020. Blue NbS in NDCs. A booklet for successful implementation (GIZ 2020). https://www.icriforum.org/wpcontent/uploads/2020/12/NbS_in_NDCs._A_Booklet_for_Successful_Implementation.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2021

Wells, G., J.A. Fisher, I. Porras, S. Staddon, and C. Ryan. 2017. Rethinking monitoring in smallholder carbon payments for ecosystem service schemes: Devolve monitoring, understand accuracy and identify co-benefits. Ecological Economics 139: 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.04.012.

Wells, G., C. Ryan, J. Fisher, and E. Corbera. 2020. In defence of simplified PES designs. Nature Sustainability 3: 426–427. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0544-3.

Williams, M., and T. Moser. 2019. The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. International Management Review 15: 45.

Wood, B.T., A.J. Dougill, C.H. Quinn, and L.C. Stringer. 2016. Exploring power and procedural justice within climate compatible development project design: Whose priorities are being considered? The Journal of Environment & Development 25: 363–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496516664179.

Wood, B.T., A.J. Dougill, L.C. Stringer, and C.H. Quinn. 2018. Implementing climate-compatible development in the context of power: Lessons for encouraging procedural justice through community-based projects. Resources 7: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources7020036.

Wunder, S., R. Brouwer, S. Engel, D. Ezzine-de-Blas, R. Muradian, U. Pascual, and R. Pinto. 2018. From principles to practice in paying for nature’s services. Nature Sustainability 1: 145–150.

Wylie, L., A.E. Sutton-Grier, and A. Moore. 2016. Keys to successful blue carbon projects: Lessons learned from global case studies. Marine Policy 65: 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.12.020.

Zeng, Y., D.A. Friess, T.V. Sarira, K. Siman, and L.P. Koh. 2021. Global potential and limits of mangrove blue carbon for climate change mitigation. Current Biology 31: 1737–1743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.01.070.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the UK Natural Environment Research Council (grant number NE/S014128/1) and the Canadian International Development Research Centre (Grant Number 109238-001) in funding the Local Roots and Global Branches project of which this paper is part of. We would also like to acknowledge Martin Kaonga from Flora and Fauna International in contributing to the first stage of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dencer-Brown, A.M., Shilland, R., Friess, D. et al. Integrating blue: How do we make nationally determined contributions work for both blue carbon and local coastal communities?. Ambio 51, 1978–1993 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-022-01723-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-022-01723-1