Introduction

The relative clause (RC) construction has been studied extensively in psycholinguistic research as it involves not only structural complexity but also word order variation. One central issue related to RC acquisition is whether young children perform better with subject-gap RCs (i.e., the RCs with a gap in the embedded subject position, abbreviated as SRCs hereafter) or with object-gap RCs (i.e., the RCs with a gap in the embedded object position, abbreviated as ORCs hereafter), and how the asymmetrical pattern should be explained. For languages with head-initial RCs like English in which the head noun precedes the RC like (1), the findings from previous research are fairly consistent. English-speaking adults are found to process SRCs like (1a) faster and more accurately than ORCs like (1b) (e.g., Traxler, Morris, & Seely, Reference Traxler, Morris and Seely2002; Gibson, Desmet, Grodner, Watson, & Ko, Reference Gibson, Desmet, Grodner, Watson and Ko2005; Grodner & Gibson, Reference Grodner, Gibson and Watson2005). Similarly, young English-speaking children are found to acquire earlier and perform better with SRCs in (1a) than with ORCs in (1b), and such a pattern is uniform across different methodologies, including corpus analyses on naturalistic speech (e.g., Diessel & Tomasello, Reference Diessel and Tomasello2000), imitation tasks (e.g., Diessel & Tomasello, Reference Diessel and Tomasello2005), as well as production and comprehension tasks (e.g., Kidd & Bavin, Reference Kidd and Bavin2002; Zukowski, Reference Zukowski2009).

Unlike the consistency observed in the studies on English head-initial RCs, the findings on Mandarin head-final RCs are quite conflicting. Mandarin has the so-called head-final RCs in which the head noun follows the restrictive clause, as illustrated in (2), and such head-final configuration has been utilized as a test case to evaluate various accounts proposed to explain the subject-object asymmetry found in English head-initial RCs.

However, to date, the issue of whether Mandarin-speaking children perform better with SRCs or ORCs remains unresolved. While most experimental studies show a clear advantage of SRCs over ORCs in Mandarin-speaking children’s comprehension and production performance (e.g., Hsu, Hermon, & Zukowski, Reference Hsu, Hermon and Zukowski2009; Tsoi, Yang, Chan, & Kidd, Reference Tsoi, Yang, Chan and Kidd2019), a recent corpus study by Chen and Shirai (Reference Chen and Shirai2015) found the opposite pattern and argued for an object-gap primacy in Mandarin-speaking children’s acquisition of RCs. This study aims to better understand why ORCs are dominant in Mandarin-speaking children’s early speech. We examined the RC utterances produced by ten children and their caregivers from a certified corpus, and classified the utterances into genuine restrictive-RCs and pseudo-RCs based on their syntactic and pragmatic properties. Overall, restrictive-RCs and pseudo-RCs are found to exhibit distinct distributional patterns, suggesting that the development of these two types of RCs is influenced by different factors.

RC acquisition in Mandarin

Much research has been done to examine how Mandarin-speaking children perform SRCs vs. ORCs (as shown in (2)). Table 1 presents a summary of the previous studies that directly focused on comparing young children’s acquisition of SRCs and ORCs in Mandarin.1

Table 1. A summary of previous studies on SRC/ORC acquisition in Mandarin

Note: The two studies by Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Gavarrò and Guasti2016) listed in the table were taken directly from Hu (Reference Hu2014)’s dissertation.

Among the six comprehension studies, four showed a clear SRC advantage (Cheng, Reference Cheng1995; Lee, Reference Lee and Lee1992; Hu, Gavarró, Vernice, & Guasti, Reference Hu, Gavarró, Vernice and Guasti2016; Tsoi et al, Reference Tsoi, Yang, Chan and Kidd2019). Chang (Reference Chang1984) and He, Wu, & Li (Reference He, Xu and Ji2017) did not find an SRC advantage, but a careful review of these two studies suggests that their results were probably confounded either by the test materials or by the task. Chang (Reference Chang1984) mistakenly used passive SRCs as the test materials for the ORC condition, and this could be a possible explanation as to why the study did not find a clear difference between the SRC and ORC conditions. In the He et al. (Reference He, Xu and Ji2017) study, a picture-selection task was used in which the child participants were asked to choose the matching picture instead of the matching head referent. As pointed out by Arnon (Reference Arnon, Brugos, Clark-Cotton and Ha2005) and Adani (Reference Adani2011), selecting pictures alone can be problematic because it is possible for children to choose the correct picture but misinterpret the target sentence. Hu (Reference Hu2014) also demonstrated that using a picture-selection task to test Mandarin RCs is especially inappropriate due to its head-final property.

Recently, Yang, Chan, Chang, & Kidd (Reference Yang, Chan, Chang and Kidd2020) used a visual-world eye-tracking paradigm to test 4-year-old Mandarin-speaking children’s online processing of SRCs and ORCs. They found a clear subject-gap advantage for DE-RCs (i.e., the head noun of the RC was a bare noun, like [mama mai de] wanju), but not for DCL-RCs (i.e., the head noun of the RC was preceded by a demonstrative-classifier combination, like [mama mai de] na-ge wanju). The difference found between DE-RCs and DCL-RCs is interesting, but this pattern requires further verification because other studies using DCL-RCs as test materials did elicit a clear subject-gap advantage (e.g., Lee, Reference Lee and Lee1992). The previous studies that focused on production performance all reported a clear SRC advantage (Cheng, Reference Cheng1995; Hsu et al. Reference Hsu, Hermon and Zukowski2009; Hu, Gavarró, & Guasti, Reference Hu, Gavarró, Vernice and Guasti2016). Lastly, Hsu’s (Reference Hsu2014) sentence imitation study suggests that the subject-object asymmetry in RC performance is correlated with age such that the SRC advantage becomes more and more evident as children grow from three to five.

While a clear SRC advantage was found in most of the experimental studies and different accounts have been proposed to explain the asymmetry,2 a clear ORC preference was reported by Chen and Shirai (Reference Chen and Shirai2015). In order to uncover the characteristics and the development of RCs in child Mandarin, Chen and Shirai (Reference Chen and Shirai2015) examined the spontaneous speech data of four Mandarin-speaking children (age 0;11 to 3;5) and their caregivers from the Fang corpus collected in China (Min, Reference Min1994). Chen and Shirai extracted and coded all noun-modifying phrases headed by the RC marker DE, and classified them based on (a) the syntactic role of the head noun in the main clause and (b) the syntactic role of the relativized noun inside the RC. They found that the majority of the RCs that the children produced modified an isolated NP rather than a subject NP or an object NP of a matrix clause, as shown in (3a). Importantly, they found that both the children and the caregivers produced overwhelmingly more ORCs like (3c) than SRCs like (3b) in their conversations (Child speech: ORCs vs. SRCs: 61.5% vs. 18.6%; Caregiver speech: ORCs vs. SRCs: 58.6% vs. 17.6%).

Chen and Shirai further showed that at the earliest stage of language development (age range 1;4~2;0), the most frequent type of RC was the combination of an isolated NP and a ORC as in (3a), which has a word order similar to the simple SVO sentence in Mandarin like (3d). They thus attributed the predominance of ORCs in early child Mandarin to two factors: first, the similarity of the word order between ORCs and simple SVO sentences (3a vs. 3d) in Mandarin, and second, a reflection of the distributional pattern from the caregivers’ input (Chen & Shirai, Reference Chen and Shirai2015, pp. 412~413). Based on this, they argued for a usage-based approach (e.g., Diessel, Reference Diessel2007; Diessel & Tomasello, Reference Diessel and Tomasello2000) to account for the development of RCs in child Mandarin and suggested that young children start out with the simplest syntactic structure from the input to acquire the grammar of RCs.

The corpus findings of Chen and Shirai (Reference Chen and Shirai2015) provide an insightful perspective into the issue of RC acquisition in Mandarin. However, several relevant issues arise. First, an obvious inconsistency was observed between the experimental findings and the corpus findings on the acquisition of Mandarin head-final RCs: the experimental results show a dominant SRC advantage (e.g., Hu, et al., Reference Hu, Gavarrò and Guasti2016; Tsoi, et al., Reference Tsoi, Yang, Chan and Kidd2019) whereas the corpus data suggests an ORC advantage (Chen & Shirai, Reference Chen and Shirai2015). This is unlike the consistent pattern found in English between the experimental findings (e.g., Diessel & Tomasello, Reference Diessel and Tomasello2005; Kidd & Bavin, Reference Kidd and Bavin2002) and the corpus data (Diessel & Tomasello, Reference Diessel and Tomasello2000). It should be noted that we do not assume that corpus findings and experimental findings must conform to each other as these two involve different contexts and processes: the former derives from children’s usage of RCs in natural contexts whereas the latter is generated from testing children’s linguistic knowledge of RCs in well-controlled settings. It is possible that certain pragmatic factors involved in the conversational context but not in the experimental setting could prompt young children to use more ORC sequences, and this is what the current study intends to find out.

Second, we also observe a clear divergence between Mandarin-speaking caregivers’ speech data and the findings from previous corpus studies on adult Mandarin. In Chen and Shirai (Reference Chen and Shirai2015) study, Mandarin-speaking caregivers were found to produce many more ORCs than SRCs when talking to their children (ORCs vs. SRCs: 58.6% vs. 17.6%). Yet, previous corpus studies consistently show that Mandarin adults use SRCs far more often than ORCs under various contexts, as summarized in Table 2. The sharp contrast in the use of RCs between Mandarin caregivers’ speech data and Mandarin adults’ other corpora data led us to speculate whether there may be something peculiar about child-adult conversation that promotes Mandarin-speaking caregivers to use more ORCs than SRCs.

Table 2. Summary of the previous corpus studies on adults’ use of RCs in Mandarin

Lastly, Chen and Shirai (Reference Chen and Shirai2015) did not specify the restricted nature of the early RC sequences in the conversational context. Chen and Shirai (Reference Chen and Shirai2015) highlighted the role of frequency (i.e., input distribution) as the key factor in the acquisition of RCs. However, the use of RCs in the conversational context is likely to be related to some kind of pragmatic factor and this may result in certain distributional properties (e.g., Fox & Thompson, Reference Fox and Thompson1990). Thus, it is important to further examine the syntactic property and the pragmatic nature of the RCs used in spontaneous child Mandarin, and the findings can offer some insights into the discrepancies discussed above.

Restrictive-RCs vs. Pseudo-RCs

To examine the specific properties of RCs produced in natural adult-child conversations, we begin by looking at the discourse functions of RCs under different contexts. First, the RCs used in the experimental tasks or identified in various adult corpora (as shown in Table 1-2) are considered to be restrictive-RCs that serve to modify a head noun, as in (4). The head noun, the woman, is discourse-old information as it has been introduced in the prior discourse (i.e., There are two women.). The RC, that wears a red hat, provides additional presupposed knowledge known to both the speaker and the hearer to differentiate the head referent out of a set of identical objects in the context (i.e., two women). Restrictive-RCs have a restricting function and are therefore most felicitous when the given context contains two or more than two identical objects.

In spontaneous speech, some constructions look superficially similar to restrictive-RCs, but they actually function as nonrestrictive predicates. For example, in (5a), the copula, is, establishes a referent (Mom) in a focal position for the predication expressed by the clause, that wears a red hat, and the clause is nonrestrictive. Sentences like (5) are known as cleft sentences, which typically put a particular constituent into focus and are often accompanied by a special intonation. Following Weinert and Miller (Reference Weinert and Miller1996), there are variations of cleft constructions in the deictic terms (it/that/what), but all involve a copular be verb, as shown in (5). We call the clause following the focused constituent in (5a) and the clauses introduced by the wh-word in (5b-5d) together as cleft clauses. Specifically, the cleft clause in (5a) looks identical to the restrictive RC in (4) on the surface. Most formal linguistic analyses treat cleft structures much the same way as RC structures because they all involve syntactic movement to the left periphery (See a brief review in Thornton, Kiguchi, & D’Onofrio, Reference Thornton, Kiguchi and D’Onofrio2018).

Another type of clause which looks superficially similar to restrictive-RCs but also functions as a nonrestrictive predicate is the so-called presentational relative clause (abbreviated as presentational-RCs) like (6). According to Lambrecht (Reference Lambrecht1988), the presentational-RC construction involves a copula be verb and a predicate nominal. In this construction, a referent is established in a focal position being predicated by a presentational-RC. The propositional content of presentational-RCs like (6) is not pragmatically presupposed but is used to assert new information related to the head referent, and so the information structure of presentational-RCs differs from that of restrictive-RCs (Lambrecht, Reference Lambrecht1988; Fox & Thompson Reference Fox and Thompson1990). Because presentational-RCs are propositionally simpler and are found to appear fairly frequently in child English, they have been argued to be related to the development of restrictive-RCs (Diessel & Tomasello, Reference Diessel and Tomasello2000).

Considered together, cleft clauses like (5a) and presentational-RCs like (6) share similar syntactic and pragmatic functions. Syntactically, they are both predicate nominals that co-occur with a copular verb, and pragmatically, they both involve some kind of focus effect to direct the listener’s attention to particular entities (Weinert & Miller, Reference Weinert and Miller1996; Diessel & Tomasello, Reference Diessel and Tomasello2000). Due to these characteristics, seeming RCs like (5-6) have been categorized as pseudo-relatives (abbreviated as pseudo-RCs) in order to differentiate them from genuine restrictive-RCs like (4) (Labelle, Reference Labelle1990). Interestingly, pseudo-RCs are found to occur fairly frequently in both adult speech (Duffield & Mickaelis, Reference Duffield and Michaelis2011) and child speech (Labelle, Reference Labelle1990). The surface similarity between pseudo-RCs and restrictive-RCs led us to suspect that perhaps a large portion of the RCs observed in Mandarin-speaking children’s and caregivers’ speech are not genuine restrictive-RCs, but instead, are pseudo-RCs that involve a focus effect in the conversational context.

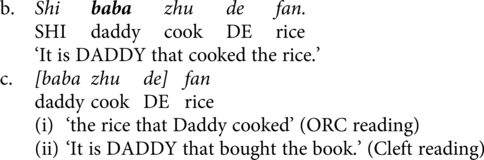

In Mandarin, the cleft construction, also called the shi…de construction, is marked by the presence of two elements, the copula shi and the morpheme de. The constituent to the right of copula (SHI) receives a focus reading, as in (7a). Subject-focus cleft sentences like (7a) have a variant like (7b), in which de is inserted between the verb and its object, creating a subject-focus V-de-O cleft. The use of subject-focus S-V-de-O clefts is related to dialectal differences and is constrained by factors such as past-time event, indefiniteness tendency, common collocations, and structural simplicity (See more discussion on this alternative in Hole, Reference Hole2011, Lee, Reference Lee2005a; Long, Reference Long2013, Paul & Whitman, Reference Paul and Whitman2008). In addition, as shown in (7c), the copular shi of the cleft sentences is often dropped in colloquial Mandarin (Cheng Reference Cheng2008; Hsieh, Reference Hsieh1998; Lee, Reference Lee2005b). Thus, a surface sequence like (7c) has two possible readings (i-ii). It is usually treated as an ORC when appearing in isolation but it could actually be a cleft sentence with a subject-focus reading in certain contexts, as exemplified in (8). In (8), Speaker B produced an utterance like (7c) as a response to the question proposed by Speaker A asking about the agent of cooking, and the subject baba ‘Daddy’ was under focus in that context. In (8), the copular SHI is placed inside a parenthesis to indicate its optionality.

Furthermore, head nouns are allowed to be omitted in Mandarin, and Mandarin-speaking children are found to produce headless DE-marked NPs fairly early (Packard, Reference Packard1988). The omission of the head noun occurs often in conversations because the head referent can be easily recovered from the prior discourse context (Cheng, Cheung, & Huang, Reference Cheng, Cheung and Huang2011). Thus, for a surface sequence like (9) where the head noun is omitted, there is likely to be ambiguity between two readings: the headless ORC reading (i) and the cleft clause reading (ii). The cleft reading of (9-ii) is a typical response to questions like (10a), which highlights the agent of cooking. To answer the question in (10a) in colloquial speech, people tend to drop the copular shi and omit the topicalized deictic pronoun zhe ‘this’ which refers to the object, as shown in (10b), resulting in a sequence like (9) that has the cleft reading (ii).

In addition to the cleft clauses, it is also observed that Mandarin speakers, both adults and children, use a lot of presentational-RCs like (11) to introduce new referents into the discourse. In these examples, the copular verb, SHI, is coupled with the deictic pronoun zhe ‘this’ or na ‘that’ to refer to something in the immediate context, and the presentational-RCs are a part of the nominal predicate, asserting new information to highlight what is special about the head noun.

To sum up here, it is clear that genuine restrictive-RCs and pseudo-RCs differ in both syntactic properties and pragmatic functions. Syntactically, restrictive-RCs involve two main propositions and serve to modify a head noun, whereas pseudo-RCs involve the copular be verb and serves as nonrestrictive predicates. Pragmatically, restrictive-RCs are about presupposed knowledge known to both the speaker and the hearer and are used to identify the head referent out of a set of similar referents, whereas pseudo-RCs assert new information and tend to involve some kind of focus effect to direct the listener’s attention to particular entities in the discourse context. Importantly, as suggested above, without considering the discourse context, utterances like (7c), (9), and (11) can easily be misanalysed as restrictive-RCs when they are in fact focus-related pseudo-RCs. Given that utterances involving focus effect appear very often in natural speech (Labelle, Reference Labelle1990; Lambrecht, Reference Lambrecht1988), we wonder if most of the RC utterances found in Mandarin child-caregiver conversations are not genuine restrictive-RCs like (2), but, instead, are pseudo-RCs that involve a focus effect in the conversational context. Specifically, we hypothesize that the pragmatic factor for using pseudo-RCs extensively is the underlying cause for the object-gap primacy observed in Mandarin child-caregiver conversation.

The Current Study

The goal of the present study is twofold. The first is to verify whether the object-gap primacy found in Chen and Shirai (Reference Chen and Shirai2015) can be replicated in a different corpus of child Mandarin. Based on this, our second goal is to carefully examine whether the object-gap primacy is related to the use of pseudo-RCs for focus effect during child-caregiver conversation. To this end, we analyzed the speech data from the Taiwan Corpus of Child Mandarin (TCCM) and incorporated the conversational context into our analyses to see how the two different types of RCs (restrictive-RCs vs. pseudo-RCs) are distributed in child speech.

Methodology

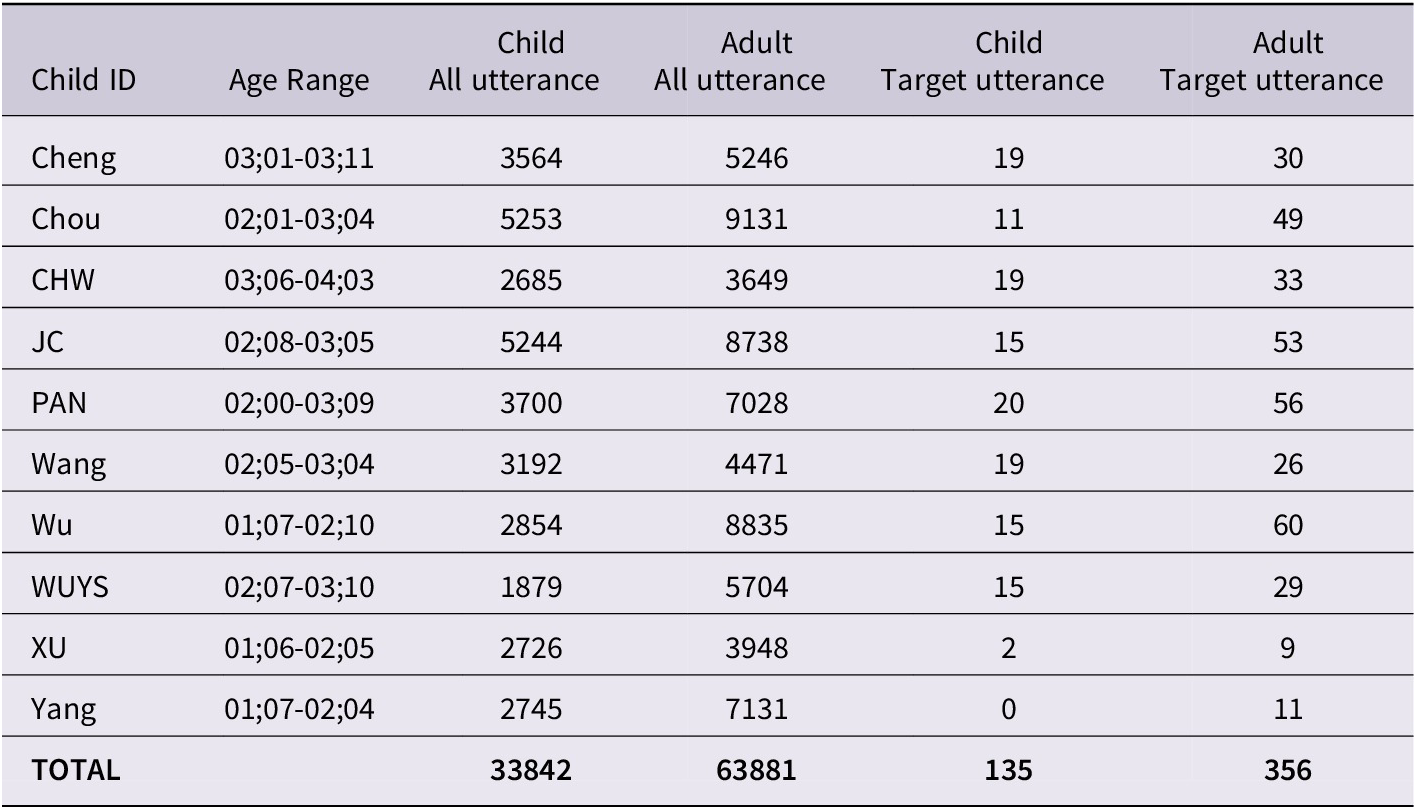

TCCM is the first public database that contains spontaneous speech data of child Mandarin in Taiwan (Cheung, Chang, Ko, & Tsay, Reference Cheung, Chang, Ko and Tsay2011), which is now a part of the TalkBank collection. It contains the speech data of ten children (age ranging from 1;6~4;3) collected from their spontaneous conversations with their caregivers (Cheung, Reference Cheung1998). In this database, the total number of child utterances and adult utterances was 33842 and 63881 respectively. Several steps were taken to filter the data. First, we extracted all the utterances that contained DE, and this gave us 1682 utterances for the child group and 4456 utterances for the caregiver group. Next, to focus our analyses on SRCs and ORCs, among the DE-marked utterances, we extracted the utterances that contained a gap in the subject position and in the object position. This gave us a total of 135 target utterances in the child group and a total of 356 target utterances in the caregiver group for further analysis. Table 3 provides detailed information of the ten paired (child-adult) participants of this study, including their age range, the numbers of total utterances, and the number of target utterances. As shown in Table 3, as Yang did not produce any target RC utterances, he/she was removed from the analysis.

Table 3. Bibliographic information of the ten children

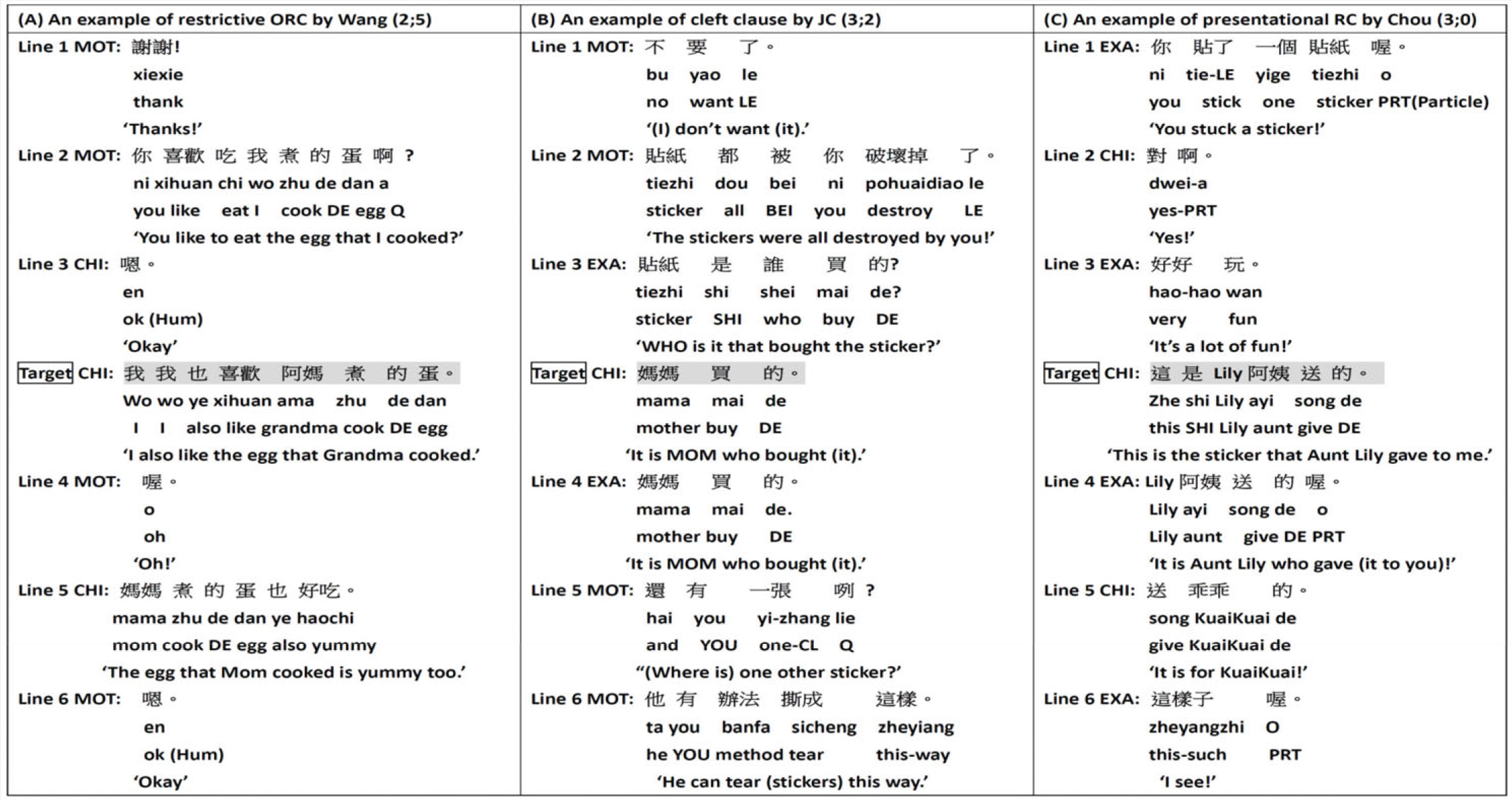

We coded the extracted target utterances in three aspects: gap position (SRC/ORC), clause type (Restrictive-RC/Pseudo-RC), and headedness (Headed/Headless). The target utterances with a [ __ V (N) de] (Head N) surface pattern were coded as SRCs (i.e., a gap in the subject position of transitive/intransitive verbs), and the target utterances with a [ N V __ de] (Head N) surface pattern were coded as ORCs (i.e., a gap in the object position). Both headed and headless sequences were included, as indicated by the parentheses. Next, we coded these target utterances as Restrictive-RC or Pseudo-RC based on their specific syntactic and pragmatic properties. To do this, we needed to check the context where the target utterance occurred. Thus, for each target utterance, we extracted three lines (Line 1 to Line 3) preceding and three lines (Line 4 to Line 6) following the target utterance (highlighted in gray) and incorporated them into our analysis. See Table 4 for examples of one restrictive-RC (A) and two pseudo-RCs (B-C) from our data.

Table 4. Examples of the three RC types from the corpus

Note: Glossary: LE = aspect marker; BEI = passive marker; YOU = existential marker; CL = classifier; Q = question particle.

Example (A) is a dialogue between a mother (MOT) and a child (CHI), and the target sentence (ama zhu de dan ‘the egg that grandma cooked’) produced by the child is an example of a restrictive-RC. The head noun dan ‘egg’ is the object NP of the matrix clause. Crucially, the target utterance that contains a typical restrictive-RCs involves two lexical verbs, one for the main clause (xihuan ‘like’ in this case) and one for the RC (zhu ‘cook’ in this case).

Example (B) involves three participants in the conversation: the mother (MOT), the examiner (EXA), and the child (CHI), and this is an example of a cleft clause. The target utterance, mama mai de ‘mother buy DE’, was produced by the child. Without considering the context, the target utterance is easily taken as a headless ORC that modifies some entity like (something) that the mother bought. However, when the context is taken into consideration, the utterance is actually not a restrictive-ORC, but is a cleft clause that places a special focus on mama ‘mother’ to answer the question ‘WHO is it that bought the sticker?’ in the preceding context (Line 3). In other words, this target utterance occurred in an emphatic context which asked about the agent of the buying action. Thus, it is a subject-focus V-de-O cleft with an omitted head noun. Crucially, the target utterance involves only one main proposition based on the lexical verb (mai ‘buy’), and is related by a copular shi, which is omitted here.

Example (C) is a dialogue between the examiner and the child participant, and it is an example of a presentational-RC. The target utterance (Zhi shi Lily ayi song de) is not a restrictive-ORC like Example (A), because only ONE sticker was introduced in the prior context by the examiner (Line 1). Based on the context, it was clear that the child was emphasizing the person (Aunt Lily) who gave the sticker to him. This is supported by Line 4, in which the examiner repeated the name of the agent (Aunt Lily) again. Thus, the target utterance was a presentational-RC with an omitted head noun, and it introduced new information about the referent (i.e., WHO provided the sticker) with some kind of focus effect. Crucially, like Example (B), the target utterance in (C) acted as a nonrestrictive predicate nominal of the copular SHI, and involves only one main proposition based on the lexical verb (song ‘give’).

Analyzing the context of the target utterances like those in Table 4 is critical to our study, because we want to see how many of the SRCs/ORCs are pseudo-RCs correlated with an emphatic reading and how many of them are genuine restrictive-RCs. The target utterances were coded either as a restrictive-RC or as a pseudo-RC based on the preceding/following context. To avoid subjective interpretation of the context, an objective criterion in determining whether the target sequence is a pseudo-RC is to see whether it is associated with the copular SHI, serving as a part of nonrestrictive predicate nominal (as Example B/C in Table 4)). It should be noted here that the use of SHI is often omitted in colloquial speech, like the target utterance in (B), so incorporating the preceding context (Line 1-3) into our analyses becomes necessary. If the target sequence contains two main propositions and does not involve copular SHI, like Example (A), it is coded as a restrictive-RC. Lastly, to see whether the omission of the head noun may be correlated with different types of RCs, the target utterances were further coded as Headed (when the head noun is present) and Headless (when the head noun is absent). To ensure the quality of the coding, three native Mandarin speakers were given clear instructions to code the data independently. Most of the data were coded the same (over 90%), and the three coders later discussed and reached agreement on the coding of all data.

Results and Discussion

Quantitative Results

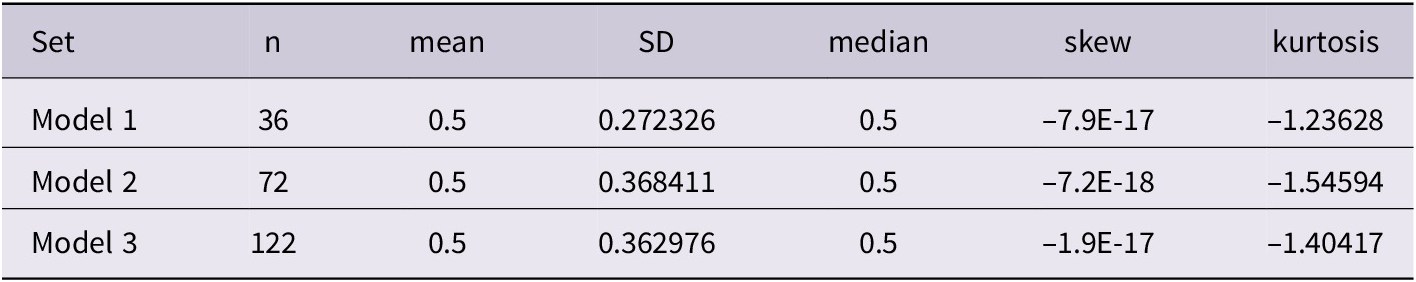

This section reports the quantitative results of our corpus analyses. Our goal was to verify whether Mandarin-speaking children used more ORCs than SRCs, and to further examine how the distribution of SRCs/ORCs may interact with Clause type (restrictive-RC/Pseudo-RC) and Headedness (headed/headless). Since the corpus used in the present study includes the speech data set of ten individual children and their caregivers (Table 3), the number of observations on the child-based target structure can be obtained. In our following statistical analyses, for comparability across individuals, we used proportions instead of raw counts as the dependent variable. As shown in Table 3, the number of extracted target utterances varies in each child-adult pair (e.g., the number of target utterances was 20 for PAN but only 2 for XU; the number of target utterances was 60 for Wu-paired adult but only 9 for XU-paired adult). Given the unequal size of the target utterances extracted from each participant, using raw counts for comparison could be problematic. For example, it was found that PAN produced 6 SRC and XU produced only 1 SRC. Based on the raw counts, PAN produced many more instances of SRC than XU did (6 vs. 1). However, if we take into account the size of the total extracted target utterances (i.e., as the denominator), the proportion of SRC is 30% (6/20) for PAN but 50% (1/2) for XU, suggesting that XU produced more SRCs than PAN proportionally. Therefore, using proportions of the target structure can better represent the appearance of the target structure in each child’s corpus than using raw counts. We ran three sets of factorial linear-mixed model (LMM) analysis with Child-Adult Pair ID (Child ID) as the random factor. We ran the analyses by using mixed function of afex package (Singmann, et al., Reference Singmann, Bolker, Westfall, Aust and Ben-Shachar2021) in the R environment (R Core Team, 2020), followed by the relevant simple main effect comparisons estimated from the pair function in the emmeans package (Lenth, Reference Lenth2020). To ensure that our data were suitable for LMM analyses, we used the describe function of the psych package (Revelle, Reference Revelle2019) to check the distribution of our dependent variable in the three LMM models. In all the three data sets, the mean and the median of the dependent variable were equal to 0.5 and the skew approached zero (Please see Table A1 in the Appendix for a complete description). These results proved that the data in the three models are normally distributed, matching the requirement for running LMM analyses.

First, we examined the effect of gap position (SRC vs. ORC) and the group (child vs. adult) difference. Table 5 presents the proportions of SRC/ORC for each participant in both groups. The proportions were calculated based on the total number of target utterances produced by each participant. It was observed that both groups produced many more ORCs than SRCs. The fixed effects of the first LMM were GAP (SRC, ORC) and GROUP (child, caregiver) exploring the relationship between GAP and GROUP and the difference of GAP distribution within GROUP. The results revealed no interaction between GAP and GROUP (p > .1), but a significant main effect of GAP (b = -0.44, SE = 0.06, t = -7.96, p < .001). The simple main comparisons of SRC-ORC show that the mean proportion of ORC was significantly higher than that of SRC in both groups (Child group: 72.3% vs. 27.7%; b = -0.45, SE = 0.08, t = -5.73, p < .001; Adult group: 71.5% vs. 28.5%; b = -0.43, SE = 0.08, t = -5.53, p < .001). Thus, there is object-gap primacy, similar to what was found in Chen and Shirai (Reference Chen and Shirai2015).

Table 5. The proportions of SRC/ORC of each participant in each group

Second, when taking the clause type (restrictive-RC vs. pseudo-RC) into consideration, interesting patterns emerged. Figure 1 presents the mean proportions of these constructions in our data (the proportions of SRC/ORC for each participant are provided in Table A2 in the Appendix). Clearly, an interaction pattern between the gap and the clause type was observed in each group. The fixed effects of the second LMM were Clause Type (CTYPE) (restrictive-RC, pseudo-RC), GAP (SRC, ORC), and GROUP (child, caregiver), to explore the relationship among these factors and the differences of GAP distribution within Clause Type. The results revealed a significant interaction between GAP and CTYPE (b = 0.99, SE = 0.17, t = 5.89, p < .001), confirming the observed pattern that overall, the mean proportion of SRCs was significantly higher than that of ORCs for restrictive-RCs (58.74% vs. 41.26%; b = 0.17, SE = 0.08, t = 2.09, p < .05), but the opposite pattern was found for pseudo-RCs (87.96% vs. 12.94%; b = -0.76, SE = 0.08, t = -9.07, p < .001) (See Figure 2). The simple main comparisons showed that in restrictive-RCs, the proportion of SRC was significantly higher than that of ORC in the child group (64.2% vs. 35.8%; b = 0.28, SE = 0.12, t = 2.40, p < .05), but not in the adult group (53.3% vs. 46.7%; p = .58). In pseudo-RCs, both groups used significantly more ORCs than SRCs (Child group: 85.1% vs. 14.9%; b = -0.70, SE = 0.12, t = -5.93, p < .001; Adult group: 90.8% vs. 9.2%; b = -0.82, SE = 0.12, t = -6.89, p < .001). These results suggest that the ORCs produced by the children and the caregivers are predominantly pseudo-RCs. Once pseudo-RCs were identified and separated, the proportion of restrictive-SRCs outweighed restrictive-ORCs, and the SRC advantage was evident in the child group but not in the adult group.

Figure 1. The mean proportions of SRCs & ORCs across Clause type in each group

Figure 2. The interaction between Gap and Clause Type

Lastly, we included the factor of “headedness” in our analyses to see if the omission of the head noun is related to gap position and clause type. Figure 3 presents the mean proportion of headed/headless utterances across clause type and gap position in each group. It was observed that in both groups, headed/headless utterances went the opposite direction between the restrictive-RCs and the pseudo-RCs, and the difference was more evident in ORCs. The fixed effects of the third LMM were HEAD (Headed, Headless), CTYPE (restrictive-RC, pseudo-RC), GAP (SRC, ORC), and GROUP (child, caregiver), to explore the relationship among these factors and the differences of Headedness distribution within CTYPE and GAP. The results showed a significant three-way interaction among HEAD x CTYPE x GAP (b = -0.75, SE = 0.20, t = -3.7, p < .01) and a significant interaction between HEAD and CTYPE (b = 0.85, SE = 0.10, t = 8.33, p < .001). The analyses confirmed the observed pattern that pseudo-RCs had more headless sequences than headed ones for both SRCs and ORCs, whereas restrictive-RCs had more headed sequences than headless ones, but only for ORCs not SRCs (See Figure 4). Interestingly, we also found a significant interaction between HEAD and GROUP (b = 0.37, SE = 0.10, t = 3.8, p < .01). As shown in Figure 5, the child group produced more headed RCs than headless RCs, though the difference was not significant (p > .1), but the caregiver group produced significantly more headless RCs than headed RCs (b = -0.29, SE = 0.07, t = -4.20, p < .001). Further simple main comparisons of Headed-Headless showed that in restrictive-RCs, the proportions of headed sequences were significantly higher than that of headless ones only in ORCs in both groups (Child group: 87.5% vs. 12.5%; b = 0.75, SE = 0.17, t = 4.32, p < .001; Adult group: 71.4% vs. 28.6%; b = 0.43, SE = 0.13, t = 3.31, p < .01). In pseudo-RCs, the proportions of headless sequences were significantly higher than that of headed ones in ORCs in both groups (Child group: 71.7% vs. 28.3%; b = -0.43, SE = 0.13, t = -3.36, p < .001; Adult group: 89.7% vs. 10.3%; b = -0.83, SE = 0.13, t = -6.44, p < .001), as well as in SRCs for the adult group (87.5% vs. 12.5%; b = -0.75, SE = 0.16, t = -4.73, p < .001). The overall pattern shows that restrictive-RCs and pseudo-RCs differ in the property of headedness. The finding suggests that in the context for using pseudo-ORCs, the head noun is often omitted, whereas in the context for using restrictive-ORCs, the head noun is more likely to be preserved. The summary table of the three LMM outputs reported above is provided in Table A3 in the Appendix.

Figure 3. The mean proportions of headed/headless RCs across Clause type and Gap position in each group

Figure 4. The three-way interaction between HEAD, CTYPE, and GAP

Figure 5. The interaction between HEAD and GROUP

Qualitative Analyses

In addition to the averaged patterns reported above, we also examined the data at the individual level. As shown in Table A2 in the Appendix, for pseudo-RCs, a clear object-gap dominance was found in every child participant (except for Cheng) and in every adult participant. For restrictive-RCs, six out of nine children produced more SRCs, and only three of them (Chou, JC, Wang) produced more ORCs. Interestingly, among the total of fifteen restrictive-ORCs produced in the child group, more than half of them were produced by Child Wang, who produced eight instances of restrictive-ORCs.

We examined the pattern of the earliest RCs produced by the children to see if the qualitative analyses support the quantitative results. A total of nine examples (12~20) were analyzed, one from each child, and they are the very first RCs produced by the children in this dataset. In these nine examples, three of them are restrictive-RCs (12~14), and six of them are pseudo-RCs (15~20). The restrictive-RCs involve two main propositions (two verbal predicates), one for the RC and one for the matrix clause, as exemplified by (12) and (13). The example in (14) by WANG is a bit tricky. The sequence ‘ mama cook de’ might look ambiguous on its own at first. The preceding line suggests the child was playing the role of Mother, and the following line ‘You don’t eat it’ suggests that the child intended to say something like ‘Don’t eat something that mom cooked’. Since this utterance did not involve a copular verb from the preceding context, it was coded as a restrictive-ORC.

The other six examples (15~20) are considered as pseudo-RCs because they all involve the copular verb SHI, which was dropped in most of the cases. They are all ORCs, with four headless (15~18) and two headed (19-20). Example (15) and (16) are typical cleft clauses, and in both cases, the copular SHI was dropped. In (15), the target utterance was a response to the question (about who bought something for the child). In (16), the target utterance was produced in the context where the child was pretending to be a chef cooking for the adult (See Line 3~6). Under such a context, the cooking actions were all done by the child participant. When the examiner said that the drink was good, the child immediately said it was made by GuaiGuai to highlight that it was him/her who produced the tasty drink. The focus effect was captured by the examiner, who repeated the same sentence (GuaiGuai pao de ‘It is made by GuaiGaui.’) right after. Both (15) and (16) are analyzed as cleft clauses because they both emphasized the agent of the action (Daddy in (15) and GuaiGuai in (16)).

Example (17) and (18) were about focusing on some entities in the immediate context, and these examples involve some variations. Example (17) is related to a focus effect because it puts emphasis on a specific object that the child had used. It is analyzed as a pseudo-RC because it involved the copular SHI, and it is a pseudo-cleft with an object-focus reading (see more in the Discussion section). It can be translated either as a wh-cleft clause like ‘This is what I used’ or as a reversed wh-cleft like ‘What I used is this!’, similar to the English examples in (5b/5d). In (18), the child speaker directed the attention to the two books in the context by saying ‘These are the two books that you brought’ to assert new information about the books, and the copular SHI was omitted.

Next, Example (19) and (20) are typical presentational clauses, like those in (11) discussed in the Introduction. These examples involve the copular verb SHI (omitted in (19) but present in (20)), and they begin with the deictic pronoun zhe ‘this’ or na ‘that’ to refer to something in the immediate context. The use of the deictic pronoun suggests that these utterances were probably coupled with a pointing gesture. These are presentational relatives because they serve as predicate nominals to highlight what is special about the head noun (wanju ‘toy’ in (19) and feifei ‘fly-fly’ in (20)). They both involve some kind of focus effect to direct the hearer’s attention to the head referent by providing new information about it.

The examples in (15-20) might be misanalysed as restrictive-ORCs based on the surface word order if their occurring context is not considered carefully. However, when looking into the context of these six utterances, they actually differ from the examples of genuine restrictive-RCs in (12-14) in terms of their syntactic properties and pragmatic functions. Overall, the pattern of the nine earliest RC-related utterances were quite revealing. Most young Mandarin-speaking children produced pseudo-RCs rather than restrictive-RCs (6 vs. 3) as their first RC-related utterance, and most of them were headless (6 out of 9). The three restrictive-RCs included two SRCs and one ORC, and the six pseudo-RCs were all ORCs. Overall, the qualitative analyses matched the quantitative results.

Analyses by age

As the age range of the ten children in our study was large (ranging from 1;6 to 4;3), in order to see the developmental path of different types of RCs, the target utterances were divided into three stages based on the children’s age (i.e., the age of the child when the utterance was produced): Stage I (age 1;6 ~ 2;6), Stage II (age 2;7 ~ 3;4), and Stage III (age 3;5 ~ 4;3). Each stage is about one year apart, and we can observe the children’s change in their use of RCs year by year. The proportions of the four types of RCs (Restrictive-SRC/Restrictive-ORC/Pseudo-SRC/Pseudo-ORC) in each stage were calculated. As shown in Table 6, throughout the three stages, the number of pseudo-ORCs was dominant (over 60%) over the other three types of RCs (Restrictive-SRC/Restrictive-ORC/Pseudo-SRC). Both Pseudo-SRC and Pseudo-ORC reached the highest proportion at Stage II (Pseudo-SRC: 14.5%; Pseudo-ORC: 64.5%). Interestingly, Restrictive-SRC and Restrictive-ORC showed the opposite patterns. The proportions of Restrictive-SRC increased steadily from Stage I to Stage III (Stage I: 10.0%; Stage II: 11.5%; Stage III: 23.3%), whereas the proportions of Restrictive-ORC declined (Stage I: 20.0%; Stage II: 9.8%; Stage III: 7.0%). These patterns suggest that in the early stage of language development, pseudo-ORCs remain dominant in child Mandarin, and that as the children grow from age 1 to 4, they begin to use more and more restrictive-SRCs than restrictive-ORCs.

Table 6. The distribution and the proportion of each RC type in each stage

General Discussion

The results of our corpus analyses yielded several important findings. First, without considering the context of where the target utterances appeared, both Mandarin-speaking children and their caregivers produced a lot more ORCs than SRCs (Table 5), parallel to the object-gap primacy found in Chen and Shirai (Reference Chen and Shirai2015). Second, when the syntactic properties and the pragmatic functions of the target SRC/ORC utterances were identified and analyzed based on the given context, we found two opposite patterns between restrictive-RCs and pseudo-RCs: (a) Pseudo-RCs displayed a clear ORC advantage whereas restrictive-RCs displayed a clear SRC advantage (Figure 1/2), and (b) Pseudo-ORCs were dominantly headless whereas restrictive-ORCs were dominantly headed (Figure 3/4). Lastly, children produced far more pseudo-RCs than restrictive-RCs, and the developmental trajectory suggests that young children use increasingly more restrictive-SRCs than restrictive-ORCs as they grow (Table 6). These findings have significant theoretical implications, as discussed below.

Experimental Findings vs. Corpus Findings

The finding that object-gap dominance occurred only in pseudo-RCs but not in restrictive-RCs suggests that the object-gap primacy found in young Mandarin-speaking children’s spontaneous speech is mainly driven by the pragmatic factor involved in the conversational context. That is, the child-caregiver conversation provides a natural context for using a lot of focus-related pseudo-RCs like subject-focus V-de-O clefts (for highlighting the agent of an action) and presentational-RCs (for asserting further information for a newly introduced object). This offers a plausible explanation for the discrepancies raised in the Introduction - why object-gap primacy is observed only in the spontaneous speech data (Chen & Shirai, Reference Chen and Shirai2015) but not in the experimental studies (e.g. Hu et al., Reference Hu, Gavarrò and Guasti2016a; Tsoi et al., Reference Tsoi, Yang, Chan and Kidd2019) or in adult written corpora (e.g. Vasishth et al., Reference Vasishth, Chen, Li and Guo2013; Hsiao & MacDonald, Reference Hsiao and MacDonald2013). Unlike natural conversations, experimental materials and written corpora normally do not involve a discourse context for focus effect, but, instead, prefer to use restrictive-RCs to modify a head referent. Our finding supports the view that the early use of RCs in spontaneous conversation is restricted in form and function, and that the discourse/pragmatic factors embedded in the conversational context affect the choice of RCs, leading to certain distributional patterns (e.g., Fox & Thompson, Reference Fox and Thompson1990; Cheng, et al., Reference Cheng, Cheung and Huang2011). In addition, our finding also suggests that the proposal of Chen and Shirai (Reference Chen and Shirai2015) to attribute the predominance of ORCs in child Mandarin to word order and input frequency is oversimplified, and the pragmatic factor should be taken into consideration.3

Pseudo-RCs vs. Restrictive-RCs

The distinct patterns found between pseudo-RCs and restrictive-RCs in our study suggest that these two types of RCs should be treated separately in the discussion of RC acquisition in Mandarin. Previous studies on head-initial RCs have suggested that these two types of RCs are developmentally related. In their corpus study on English-speaking children, Diessel and Tomasello (Reference Diessel and Tomasello2000) found that the majority of the early RCs produced by young children are presentational-RCs attached to the predicate nominal of a copula clause, and they mostly involve a subject gap with an intransitive verb like (6a). Based on this, Diessel and Tomasello (Reference Diessel and Tomasello2000) argued that children start out from a presentational amalgam construction (a copular clause plus a relative) which expresses a single proposition, and gradually they learn to use complex relative constructions by expanding the structure into two full separate clauses with two main propositions (pp. 142-143). Young French-speaking children are also found to use a lot of presentational-RCs and cleft clauses with a subject gap, and Labelle (Reference Labelle1990) took this observation to support her proposal that early child relativization does not involve wh-movement but is a result of grammar transfer from the predicative construction employed in presentational-RCs and clefts (pp. 113-114). These studies point toward the assumption that pseudo-RCs act like precursors to restrictive-RCs in the acquisition of RCs. However, our findings on head-final RCs in Mandarin challenge this view, because pseudo-RCs and restrictive-RCs exhibit contrasting characteristics. First, the developmental trajectory for restrictive-RCs and pseudo-RCs show totally different patterns (Table 6). The dominant use of pseudo-ORCs in early child Mandarin suggest that object-gap sequences should be easier to acquire. But this is not what we found in restrictive-RCs, where SRCs are used more often than ORCs as children mature. Second, if the development of restrictive-RCs is structurally influenced by pseudo-RCs, we would expect to observe an ORC advantage and a preference for head omission in restrictive-RCs, similar to what is found in pseudo-RCs. Yet, this is not the case. Instead, we found a SRC advantage and a preference for being headed in children’s use of restrictive-RCs. The dissimilar distributional patterns between restrictive-RCs and pseudo-RCs suggest that these two types of RCs are probably inherently different in Mandarin and should be discussed separately.

In our study, pseudo-RCs include both presentational-RCs and subject-focus V-de-O clefts, in contrast to restrictive-RCs. Although they share surface similarity in word order, only presentational RCs, but not V-de-O clefts, have an underlying structure similar to restrictive-RCs. This differs from English, where both presentational-RCs and cleft clauses are regarded to be derived via similar processes like restrictive-RCs (i.e., movement to the left periphery). Under the generative framework, it is generally agreed that the Mandarin RC construction involves wh-movement like English, and presentational-RCs also involve similar derivation like restrictive-RCs, albeit being attached to a predicate nominal instead of an argument NP (Huang, Li, and Li, Reference Huang, Li and Li2009). While young children’s earliest presentational-RCs are mostly object-gap like (19-20), they also produce a few subject-gap presentational-RCs, as in (21-22). In these examples, the head noun (Dasin in (21) and fenhongse-de wazi ‘pink socks’ (omitted) in (22)) is specific and the presentational-RC is part of the predicate nominal (with omitted SHI) that asserts new information to highlight the head noun.

The cleft construction in Mandarin, however, is structurally very different from restrictive-RCs and presentational-RCs. In Mandarin, subject-focus S-V-de-O clefts like (23a) are usually considered to be marked variants of S-V-O-de clefts (23b). Various syntactic analyses on subject-focus V-de-O clefts have been proposed, depending on how DE is analyzed. Some opt for a unified analysis of DE for both clefts and RCs (Cheng, Reference Cheng2008; Long, Reference Long2013; Simpson & Wu, Reference Simpson and Wu2002), while others treat DE in clefts and DE in RCs as two independent morphemes (Lee, Reference Lee2005b; Paul & Whitman, Reference Paul and Whitman2008). The dominant view is that the derivation of Subject-focus V-de-O cleft does not involve wh-movement like restrictive-RCs (Hole, Reference Hole2011; Paul & Whitman, Reference Paul and Whitman2008; Simpson & Wu, Reference Simpson and Wu2002).4

We think that there may be something peculiar about Chinese shi…de clefts that contributes to the object-gap dominance found in pseudo-RCs in our study. That is, an object NP is not allowed to be positioned to the right of SHI as a focused constituent (Teng, Reference Teng1979; Huang, Reference Huang1988; Tsao, Reference Tsao1994). In English, an object NP is allowed to be moved into It is … that configuration to have an object-focus reading as in (24a). However, in Mandarin, due to some special syntactic restrictions, an object cleft in a shi…de construction like (24b) is unacceptable (Huang, Reference Huang1988; Tsao, Reference Tsao1994; Yang & Ku 2010). The best way to represent the object-focus reading of the English cleft in (24a) is to use a pseudo-cleft construction like (24c), which actually involves an object-gap, like Example (17) in our data. Although Mandarin does not allow object clefts, it does allow a predicate-focus structure derived by positioning SHI right before the whole VP. In this case, the focused constituent can be the entire predicate (25a) or the object NP included in the predicate (25b) (Lee, Reference Lee2005b). This structure would produce a seeming subject-gap (with an omitted head), but it is used rather infrequently. We found only one pseudo-SRC of this kind in our corpus, shown in (26). It is a predicate-focus structure and the copular SHI is omitted.5

In brief, Mandarin has subject-focus S-V-de-O clefts which look similar to ORC word order ([N V __ de (N)]) on the surface, and because of their frequent occurrence, they are easily confused with restrictive-ORCs out of context. Mandarin does not allow an object cleft structure parallel to English example (24a), and uses pseudo-clefts like (24c) with an object-gap to express an object-focus reading unambiguously. In addition, Mandarin allows a predicate-focus structure, which generates a word order that resembles SRC word order with an omitted head noun ([ _ V N de]), but this kind of usage is quite limited in child language. These structural asymmetries of Mandarin cleft construction may be one major reason why we found so many more pseudo-ORCs than pseudo-SRCs in child-adult speech in Mandarin.

The development of different types of RCs

In our study, genuine restrictive-RCs are found to be used much less frequently and developed later than pseudo-RCs in child Mandarin. This is reasonable because restrictive-RCs are syntactically and pragmatically more complex than pseudo-RCs. As discussed in the Introduction, restrictive-RCs involve two main propositions in two full clauses and are related to the presupposed knowledge and shared information in the discourse context. Such complexity could be quite challenging for young children due to their limited cognitive capacity (Newport, Reference Newport1990). Importantly, we found a clear SRC advantage in the use of restrictive-RC in the child group, in line with the previous experimental findings (Hsu et al, Reference Hsu, Hermon and Zukowski2009; Hu et al., Reference Hu, Gavarrò and Guasti2016; Lee, Reference Lee and Lee1992; Tsoi et al., Reference Tsoi, Yang, Chan and Kidd2019, etc.). The SRC advantage can be explained either by the structure-based account (Hsu et al, Reference Hsu, Hermon and Zukowski2009; Hu et al., Reference Hu, Gavarrò and Guasti2016) or the experience-based account (Tsoi et al., Reference Tsoi, Yang, Chan and Kidd2019). The structure-based account attributes the SRC advantage to the structural factor. As subject gap is located in the highest position of a sentence, it is structurally more accessible and has fewer intervening items than the object gap (e.g., Noun Phrase Accessibility Hierarchy in Keenan & Comrie Reference Keenan and Comrie1977; Relativized Minimality in Friedmann, et al., Reference Friedmann, Belletti and Rizzi2009). The experience-based account, on the other hand, attributes the SRC advantage to the input distribution as SRCs are found to be more frequent than ORCs in various corpus studies (e.g., Vasishth et al., Reference Vasishth, Chen, Li and Guo2013). Our finding of a SRC advantage observed in the child group but not in the adult group (Figure 1) lends strong support to the structure-based account. Since the child-directed speech from the adults did not show a clear SRC advantage, the SRC advantage pattern found in the child group cannot be attributed directly to the input factor. This finding is significant because it suggests that the acquisition of restrictive-RCs is affected mainly by the structural factor rather than the input factor. Under the experience-based approach, an alternative explanation to the SRC advantage found in the previous experimental studies was the biased difficulty associated with ORCs due to the use of the animate head nouns in the test materials (e.g., Tsoi et al, Reference Tsoi, Yang, Chan and Kidd2019). However, this is not a problem in our study because our data is based on naturalistic child speech. Although various corpus studies show that Mandarin-speaking adults use more restrictive-SRCs than restrictive-ORCs (Table 2), they are mostly based on written texts and are unlikely to be the major source of input for children under age four. In our study, when pseudo-RCs are separated from restrictive-RCs, Mandarin-speaking children are found to use significantly more restrictive-SRCs than restrictive-ORCs. As no SRC advantage was observed in the paired caregivers, we suggest that it is the structural difference inherent between SRCs and ORCs that plays a critical role in affecting the development of restrictive-RCs. Moreover, in the by-age analyses, Mandarin-speaking children are found to use more and more restrictive-SRCs over restrictive-ORCs as they grow from 1 to 4 (Table 6). Such a developmental path also supports the SRC advantage in acquiring restrictive-RCs, and suggests that the SRC advantage will become more evident as children mature, corroborating the previous experimental findings (e.g., Hsu, Reference Hsu2014; Hu et al., Reference Hu, Gavarrò and Guasti2016b).

Next, our study showed the prevalence of pseudo-RCs in early child Mandarin (Table 6), which is a phenomenon found cross-linguistically. For example, Spanish-, Hebrew-, and French-speaking children were found to use a lot of presentational-RCs in narrative picture-book tasks (Dasinger & Toupin, Reference Dasinger, Toupin, Berman and Slobin1994; Jisa & Kern, Reference Jisa and Kern1998). English-speaking and French-speaking children are also found to produce a lot of RCs that are attached to the predicate nominal of a copular sentence (Diessel & Tomasello, Reference Diessel and Tomasello2000; Hudelot, Reference Hudelot1980). We suggest that the dominant use of pseudo-RCs in child speech is due to the particular communicative needs of young children (e.g., Diessel, Reference Diessel2009). Young children, especially from age 1-3, are in the process of learning to identify and to label objects/people in their surroundings. Both caregivers and young children thus tend to produce sentences with a focus effect to draw attention from each other on the specific objects/people in their conversation. Using cleft clauses can achieve the focus effect directly by positioning the element into a focused position. For example, when talking to a young child, in addition to using a neutral sentence with a focus prosody like Look! Uncle Sam bought an ICE CREAM, the caregiver may use a cleft sentence like ‘Look! It’s Uncle Sam that bought an ice cream!’ or ‘Look! It’s a book that Uncle Sam bought!’ to draw the child’s attention to the agent or the object of the buying event. In addition, when asking children questions, in order to check if they could identify certain objects or people, caregivers may say ‘Look! Who is it that bought the ice cream? / What is it that Uncle Sam bought?’ instead of ‘Who bought the ice cream? / What did Uncle Sam buy?’ So, it is natural for young children to pick up the focus reading and respond with a cleft clause.

As for presentational-RCs, they create some kind of focus effect because this type of construction is able to combine two distinct functions - referent introduction and property predication - into one single sentence at the same time. Following Lambrecht (Reference Lambrecht, Haiman and Thompson1987, Reference Lambrecht1988, Reference Lambrecht, Beyssade, Bok-Bennema, Drijkoningen and Monachesi2002), presentational-RCs are pragmatically motivated because they function to introduce a new referent in a non-initial position and this allows speakers to assert further relevant information about the newly introduced topic as a way to highlight the referent. In a lot of children’s fairytales, an opening sentence like ‘Once upon a time, there was a little princess who lived in a castle.’ is a typical example of presentational-RCs. The properties of presentational-RCs such as semantically-bleached verbs (copular), a discourse-new head nominal, and an assertion in the RC, make it a very suitable structure for caregivers and children to talk about new referents and their properties at the same time and draw attention from each other during conversation. Furthermore, there is a cross-linguistic difference in the use of presentational-RCs. Bates and Devescovi (Reference Bates, Devescovi, Bates and MacWhinney1989) showed that Italian speakers used more presentational-RCs than English speakers in a picture description task, and suggested that this difference is related to whether the language encodes a discourse topic or sentence subject. They proposed that speakers of topic-prominent languages like Italian are more likely to use presentational-RCs than speakers of subject-dominant languages like English, because the former but not the latter allows speakers to frequently introduce new referents in a non-subject position (i.e. topic position). As Mandarin is classified as a topic-prominent language (Li & Thompson, Reference Li, Thompson and Li1976), it is not surprising that Mandarin-speaking caregivers and children use a lot of presentational-RCs to talk about elements in their environment. As focus-related pseudo-RCs (both clefts and presentational-RCs) can draw the hearer’s attention and highlight certain elements in the discourse, they are pragmatically very useful in caregiver-child speech. Our finding of extensive use of pseudo-RCs in Mandarin child-caregiver conversation suggests that the special communicative needs for attention play a critical role in early language development.

Lastly, we discuss the cross-linguistic similarities and differences in young children’s use of pseudo-RCs. One issue that deserves special attention is why it is the ORC but not the SRC that is dominant in Mandarin-speaking children’s use of pseudo-RCs. This pattern differs from what is found in English. Diessel and Tomasello (Reference Diessel and Tomasello2000) showed that young English-speaking children produced a lot of subject-gap pseudo-RCs like (27). In our study, we found that young Mandarin-speaking children produced a lot of object-gap pseudo-RCs like (28).

Interestingly, although the English examples (27) and the Mandarin examples (28) differ in the gap position, they all place the focus on the agent of the action. This is especially clear when we compare (27a) and (28a). In both examples, the agent ‘Mom’ was the focus. In Mandarin (28a) ‘(Shi) mama mai __ de’, the gap appears in the object position after the verb mai ‘buy’, but in its English counterpart (27a) ‘It is MOM that ___ bought it.’, the gap appears in the subject position before the verb bought. In other words, in both languages, children prefer to highlight the agent of an action (i.e. subject-focus reading) in their use of pseudo-RCs. We suggest that there is a universal tendency for young children and caregivers to highlight and to talk about the agent of an event in their speech. This is because naturally occurring conversations often center on interactions between animate objects like humans or animals and therefore, information about agents tend to be more prominent than information about patients or objects (Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Diessel and Tomasello2008). So, it is the universal pragmatic factor that prompts the child-caregiver conversation to produce a lot of pseudo-RCs with a subject-focus reading. As for the difference in the gap position found between child English and child Mandarin (27a vs 28a), we think it is related to language-specific factors. First, English has head-initial RCs whereas Mandarin has head-final RCs. Second, the cleft construction works differently in the two languages. English derives a subject-focus reading by moving the agent NP into It is … that structure, similar to the leftward movement of RCs, and this results in a SRC. In Mandarin, however, the subject-focus reading is derived by placing the agent NP to the right of SHI in the shi … de construction, and combined with the head-final property of Mandarin RCs, this results in an ORC word order [(SHI) S V-de-O]. These structural differences account for the cross-linguistic variation, such that a subject-gap dominance is found in the pseudo-RCs of child English, whereas an object-gap dominance is found in the pseudo-RCs of child Mandarin.

Conclusion

To conclude, our study is the very first to carefully examine the use of pseudo-RCs and restrictive-RCs in child Mandarin, and the findings are noteworthy. Pseudo-RCs and restrictive-RCs differ both syntactically and pragmatically. Specifically, pseudo-RCs include both clefts and presentation-RCs, and they both involve some kind of focus effect to direct the listener’s attention in the discourse context. The distinct distributional patterns we found between pseudo-RCs and restrictive-RCs suggest that these two types of RCs should be treated separately. We found a SRC dominance for restrictive-RCs and suggest that the acquisition of restrictive-RCs is affected mainly by the structural factor. We found an ORC dominance in pseudo-RCs and suggest that the object-gap primacy is mainly the result of the need for a focus effect in child-caregiver conversation. Our findings also suggest that the extensive use of pseudo-RCs to highlight the agent of an event is an important characteristic of child-caregiver speech, and attribute it to the universal pragmatic factor and the communicative needs of young children. We also discussed the language-specific factors that are related to cross-linguistic variation on whether it is SRC or ORC that is dominant in early pseudo-RCs. Unlike English, the head-final RCs and the special structural features of the Mandarin cleft construction give rise to the ORC dominance in Mandarin-speaking children’s use of pseudo-RCs. Finally, the diverging developmental patterns between restrictive-RCs and pseudo-relatives suggest that these two types of RCs are inherently different, and the exact developmental relationship between these two types of RCs remains to be examined further.

Appendix

Table A1. Data Distribution Description

Table A2. The proportions of SRC/ORC across clause type in each child (top) and their paired adult (bottom)

Table A3. The summary table of the three LMM outputs

*p < .05; **p < .01

Note. GROUP = Child - Paired Caregiver; GAP = SRC - ORC; CTYPE = Restrictive-RC - Pseudo-RC; HEAD = Headed - Headless; * = Interaction.