Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has had significant impacts on violence against women (VAW), including increased prevalence and severity, and on VAW service delivery. The purpose of this research was to study women’s experiences with VAW services in the first stages of the pandemic and describe their fears and concerns. This cross-sectional study was conducted from May through October 2020. Our VAW agency partners across Ontario, Canada invited women using outreach services to participate in a study about their experiences during the pandemic. In total, 49 women from 9 agencies completed an online survey. Quantitative data were analyzed with descriptive statistics and open-ended responses are presented to supplement findings. Women’s experiences with VAW services during the pandemic varied greatly; some found technology-facilitated services (phone, video, text) more accessible, while others hoped to return to in-person care. Over half of women reported poorer wellbeing, access to health care, and access to informal supports. Many women reported increased relationship-related fears, some due specifically to COVID-19 factors. Our results support providing a variety of technology-based options for women accessing VAW services when in-person care options are reduced. This research also adds to the scant literature examining how some perpetrators capitalized on the pandemic by using new COVID-19-specific forms of coercive control. Although the impacts of the pandemic on women varied, our findings highlight how layers of difficulty, such as less accessible formal and informal support, as well as increased fear – can compound to make life for women experiencing abuse exceptionally difficult.

Similar content being viewed by others

As the COVID-19 pandemic persists, evidence is mounting that violence against women (VAW) – long recognized as a major social and public health problem worldwide (World Health Organization, 2013; WHO) – has become worse in two key ways (UN Women, 2020). First, many reports indicate that VAW has become more prevalent and severe (Carrington et al., 2020; Viero et al., 2021). Reasons for such increases include: greater exposure to abusers due to stay-at-home orders or unemployment; stressors such as job loss and economic uncertainty; reduced access to informal and formal supports; and increased consumption of alcohol and other substances during isolation (WHO, 2020). Second, VAW services (and others that women experiencing violence often need, e.g., housing, health care, family/criminal law) have seen major disruptions, creating additional barriers to women seeking help (Carrington et al., 2020; Lyons & Brewer 2021). Together, these factors have raised alarm bells throughout the VAW sector, exacerbating problems associated with chronic under-funding and staffing challenges, and making it especially difficult to meet the complex needs of women experiencing violence (Harris et al., 2014; Burnett et al., 2015; Maki, 2019; Trudell & Whitmore, 2020).

Research suggests VAW tends to increase during times of crisis (e.g., natural disasters; for an overview, see Viero et al., 2021; Stark & Vahedi, 2021), and predictions that COVID-19 would have similar consequences were present in the early days of the pandemic (e.g., Graham-Harrison et al., 2020; United Nations Population Fund, 2020). Around the world, news reports of increased domestic violence (DV) calls to help lines and police soon followed (Taub, 2020). Later, research confirmed such reports (Kourti et al., 2021). For example, a systematic review reported that most of the included 18 empirical studies found an increase in DV post-lockdowns, with a stronger overall effect when only American studies were considered (Piquero et al., 2021). Nevertheless, it should be noted that there were also reports of decreases in VAW-related help-seeking in the early stages of the pandemic. These decreases have been attributed to barriers to help-seeking (e.g., abusers were home and victims’ mobility was restricted due to lockdowns), as opposed to reflecting lower VAW incidents, and were balanced with VAW service staff accounts of increased complexity and severity of cases (Petersson & Hansson, 2022; Viero et al., 2021; Women’s Shelter Canada, 2020).

In addition to greater prevalence, evidence is accumulating that the severity of VAW also increased during the pandemic lockdowns (Carrington et al., 2020). For example, one American study of electronic health records of patients with reported intimate partner violence found greater severity of injuries during the pandemic compared to before; the authors suggested victims may have been delaying help-seeking until the abuse was more severe (Gosangi et al., 2021). Other studies found VAW service staff observed more severe violence among clients. For example, in a survey of 266 shelters across Canada, 52% of respondents reported that the violence experienced by women coming to shelter was somewhat or much more severe during the pandemic compared to before (Women’s Shelters Canada, 2020).

Perhaps most disturbingly, COVID-19 appears to have been ‘weaponized’ by some perpetrators to increase their coercive control over women (Pfitzner et al., 2020). Coercive control, usually associated with the most severe form of DV called ‘intimate partner terrorism’ (Johnson & Leone, 2005), is “an act or a pattern of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim” (Women’s Aid Federation of England, 2021, para. 1). This type of VAW is used by perpetrators to isolate women and regulate their behavior, ultimately depriving them of any independence from the abuser. Various commentaries, as well as research reports based on samples of providers and women, suggest that some perpetrators capitalized on stay-at-home orders by increasing their surveillance, control, and isolation of women, often using the pandemic as an excuse to do so (e.g., misinforming victim about the extent of current quarantine measures; Carrington et al., 2020; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020; Ravi et al., 2021; Trudell & Whitmore, 2020). Furthermore, although research in this area is particularly limited, evidence of new COVID-19-specific forms of coercive control have emerged. For example, there have been reports of perpetrators withholding safety products (e.g., sanitizers; National Domestic Violence Hotline, 2020) or proof of vaccination (Steacy & Burr, 2021), spreading rumors that women have COVID-19, forcing women to breach social distancing guidelines (Pfitzner et al., 2020), and threatening to infect women (or their children) with COVID-19 (Carrington et al., 2020; Haag et al., 2022). Thus, the harmful effects of COVID-19 mitigation policies (including stay-at-home orders) were largely predictable, creating a “perfect storm for controlling, violent behaviour behind closed doors” (United Nations, 2020).

In addition to escalating violence during the pandemic, VAW services also became more difficult for many to access. Due to lockdowns and physical distancing requirements, particularly in the early stage of the pandemic, VAW (and related) services were either closed, operating at reduced capacity with increased wait times, or delivered in ways that posed barriers to some women. While VAW shelters in Canada generally remained open during the pandemic, most had reduced capacity and cancelled in-person programs to comply with public health regulations (Trudell & Whitmore, 2020; Women’s Shelters Canada, 2020). Other services often accessed by women experiencing violence (e.g., municipal housing offices) were more variable in their responses, with some closing entirely for extended periods, making it even more difficult than usual for VAW staff to support women transitioning out of violent relationships (Mantler et al., 2021). In Canada and beyond, many VAW services adapted by offering technology-based supports to women (UN Women, 2020; Women’s Shelters Canada, 2020). While some women found these options effective, technology was a barrier for others, either because of access challenges (e.g., unreliable internet connections, particularly in rural areas) or they didn’t feel comfortable using technology (Carrington et al., 2020; Trudell & Whitmore, 2020; Wood et al., 2021). Moreover, for some women isolated at home with their abuser, it was not safe to access supports remotely (Pentaraki & Speake, 2020). Others delayed help-seeking in person due to concerns about contracting COVID-19, particularly in shelters (Trudell & Whitmore, 2020; Women’s Shelters Canada, 2020). Overall, help-seeking became more complicated, and decision-makers at various levels were challenged to provide VAW services safely and effectively during a pandemic (Butler et al., 2022; Lapierre et al., 2022; Petersson & Hansson, 2022).

While the evidence base regarding COVID-19 and VAW is growing, there has been a significant focus on prevalence, with less research on women’s views of services, and on COVID-19-specific violence. This paper reports the findings of an online survey with women using VAW outreach services during the early stages of COVID-19 pandemic. Our purpose was to examine women’s experiences with VAW (and related) services during this time and to describe their relationship-related fears associated with the pandemic.

Method

Procedure

The cross-sectional, online study took place between May and October 2020 and received approval from the authors’ institutional research ethics board. Woman-identifying people 18 years or older using DV or sexual assault outreach services in Ontario, Canada were eligible to participate. To recruit women, our five agency partners (who were involved as formal research partners for this multi-study project) as well as agencies contacted through a broader sector email listserv, asked their outreach staff to tell clients about the study. We provided agencies with sample recruitment text for staff and an information sheet, as well as the study URL. Staff were encouraged to use their judgment regarding who to recruit (e.g., timing may not be right for women in crisis), and it was made clear that women must consent freely with no impact on services. Staff could recruit women via their usual communication strategies (e.g., text, verbally). In appreciation for their time, women received a $10 electronic gift card via email.

Measures

The online survey took women about 20 to 30 min to complete. Following informed (online) consent, participants indicated the type of service they were currently using, whether DV counselling/outreach, sexual assault counselling/outreach or ‘other.’ Next, participants responded to questions about (a) how the transition of services (because of the pandemic) to online, phone and video chat affected them, (b) their preferences regarding service changes that should be kept and which should be discontinued (e.g., access to services via text, phone, etc.), (c) their experiences with other (i.e., non-violence-related) community services during COVID-19, (d) their fears in relationships before and since COVID-19 (e.g., fear of different forms of violence, etc.), including new pandemic-related fears (e.g., someone intentionally giving them COVID-19), (e) the overall impacts of COVID-19 including on their wellbeing, access to care, and access to informal supports, and (f) demographics. The questions related to relationships were intentionally worded broadly to be relevant for women accessing DV or sexual assault counselling services. Optional open text boxes were used throughout for participants to provide additional comments or describe their experiences.

Data Analysis

Quantitative survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (i.e., frequencies, percentages) in SPSS Version 26. Open-ended write-in responses are presented throughout as a supplement to the quantitative findings.

Results

Sample Characteristics

In total, 49 women completed the survey. Most (n = 25, 51.0%) participated in July 2020 (i.e., about 3 months into the pandemic), with the remaining approximately split before and after that time. Most women had used domestic violence services (n = 35, 71.4%) while the remaining used sexual assault services (n = 13, 26.5%); one woman did not provide information on the type of services accessed but did indicate the care was from a women’s shelter and resource center. Across participants, nine different agencies/organizations were represented. Among women who responded to this question (n = 34), age ranged from 22 to 72 years (M = 43.41, SD = 11.44). Additional sample characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Experiences with VAW Services

Women’s experiences with the transition of VAW services to online, phone and video-chat were mixed (see Table 2). Overall, 41–51% of women reported services were less accessible, safe, useful, supportive, and/or able to meet their needs. For example, one woman (P39) described her fears about video calls: “… I am scared to have a video appointment because if I have a panic attack then I don’t have any physical support at home other than my dog.” Some women, however, reported no change in these factors, or that services were better. Several women with mobility limitations or mental health challenges found services more accessible, for example: “I have really bad anxiety so it was nice to be able to text instead of meet in person and talk,” (P26) and “Video conference counselling has been very helpful, especially since I am already handicapped and find getting to the office difficult” (P10).

When asked which methods of service provision should be kept (text, online resources, phone and video), each method was endorsed by 35–49% of women. Write-in comments, however, reflected a desire for in-person care. For example,

“Counsellors have been excellent, but nothing can substitute for one-on-one visits. The presence of someone who actually understands the fear, shame, loss of self, etc. is more comforting than a video call/phone call. I could feel her support just by being in the same room the last time we had an appointment. I can’t explain it any better.” (P14).

Of the alternate methods of service provision, none received more than 6% of women suggesting their removal; write-in comments often suggested no services should be removed.

Relationship-related Fears

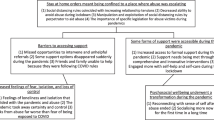

Over half of the women (51.0%, n = 25) reported being afraid in any relationship before the pandemic, and of them, 56.0% reported at least one fear had worsened (n = 14). Women’s most common relationship fear before the pandemic was a fear of being emotionally hurt; this, and many other fears increased for some women during the pandemic (see Fig. 1).

Over half of women reported not having new relationship fears specific to COVID-19 (55.1%, n = 27). The remaining women who responded had at least one (26.5%, n = 13), including fears about: ‘Someone intentionally giving you and/or your children or family COVID-19’ (16.3%, n = 8); ‘Someone preventing you (and/or children/family, if any) from getting testing or treatment for COVID-19’ (4.1%, n = 2); ‘Someone withholding or preventing you from getting safety supplies, such as masks, disinfectants, soap, etc.’ (4.1%, n = 2); ‘Someone withholding or preventing you from accessing needed supplies, such as prescription or other medications/drugs, assistive devices, contraception, etc.’ (10.2%, n = 5); ‘Someone telling other people you have COVID-19, even if you don’t’ (12.2%, n = 6); and/or ‘other’ (8.2%, n = 4; e.g., their ex-partner not following COVID-19 guidelines with their children).

Experiences with Other Services

Over a third (38.8%, n = 19) of women had used other community services since the start of the pandemic. Of these, 73.6% (n = 14) reported their needs had been met or somewhat met; 26.3% (n = 5) reported their needs were not met. Write-in comments highlighted some frustrations, for example, one woman (P44) wrote, “Everything seemed to shut down and I’ve heard nothing from no one since [COVID-19] started…” Other comments reiterated the desire for in-person support while still adhering to COVID-19 precautions, for example, “More in-person support. There is enough space to keep distance and we can wash our hands” (P21).

Many women (59.2%, n = 29) reported that accessing physical and mental health services was somewhat or much harder because of the pandemic (see Table 3). One woman (P1) wrote, “With each stage of the pandemic it changes. Not being able to have medical care is frightening. I waited for surgery for 7 months. 2 friends died while waiting for medical care. Scary.”

When given the opportunity to provide advice regarding other services, four women suggested checking in with people. For example, one (P40) reported, “Perhaps offer a check-in service for people who are isolated or at risk.”

Other Impacts of the Pandemic

Over half (55.1%, n = 27) of the women reported their wellbeing (including feelings of stress, physical and mental health) was somewhat or much worse due to the pandemic (see Table 3). For example, one woman (P45) wrote, “I am struggling to live a normal life, my mental health issues are increasing, raising lots of thoughts about self-harming. I lack motivation when trying to maintain any daily skills” and another (P43) wrote, “My depression and anxiety have worsened and I have had to increase my antidepressants.”

While their needs for support increased, available supports were more scarce—67.3% of women (n = 33) reported it was somewhat harder or much harder to access their usual informal supports since the pandemic. One woman wrote,

“For someone like me who doesn’t trust any relationships easily, it all felt very isolating. It has been very hard to get those needs met. I had to really bump up my [communication] skills. I had to really be brave and ask for what I needed.” (P38).

Over half the women (51.0%, n = 25) reported that overall the pandemic caused their lives to become somewhat or a lot worse. For example, one wrote, “Everything that would help me move forward is delayed…especially counselling, and the court system. Our lives are on hold and we’re living in a small apartment but at least we’re safe. It’s just incredibly frustrating and stressful” (P14). However, again, responses were mixed. For example, this woman found the pandemic had improved her life in an important way: “I was pretty much housebound before the epidemic, so in some ways, it’s made certain things more accessible to me because I can have them delivered without the shame/stigma I was facing before” (P10).

Discussion

To date, very little research has been done to ask women (as opposed to staff) about their preferences for how VAW services are offered during the pandemic. In this study, while some women found VAW services to be less accessible, safe, useful, supportive, and able to meet their needs, other women reported no change or that services were even better. Endorsement of specific technology-based ways of receiving care varied, suggesting that what worked for some, did not work for others. Overall, however, women supported keeping all formats available, and some, without prompting, stressed the value of in-person care. Some women, such as those with anxiety or mobility challenges, indicated technology-based formats made receiving care easier and more inclusive than it had ever been. In general, our findings are consistent with research showing many women experienced added barriers to VAW services because of the pandemic (Carrington et al., 2020; Petersson & Hansson, 2022), but also with previous assertions that ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches are generally not appropriate or effective for responding to VAW (Wathen, 2020). However, such complexity should not prevent the development of new efforts to increase safety and access to support for women.

Our findings are also in line with recent reports of increased violence severity for some women (Carrington et al., 2020; Women’s Shelter Canada, 2020). Among women with relationship-related fears before the pandemic, many reported their fears had increased, but this varied by the different forms of violence. Consistent with some previous reports (e.g., Godin, 2020; Pfitzner et al., 2020), over a quarter of women also had new COVID-19-specific fears, such as perpetrators intentionally infecting them with COVID-19. Our study represents one of the few empirical examinations of COVID-19-specific VAW to date.

This research has several limitations. First, our relatively low response rate for open-ended questions did not allow for qualitative analysis. Second, our sample size did not allow for sub-analysis of women accessing sexual assault versus DV services. Third, our research took place during a time when public health guidelines were in constant flux; our findings represent one snapshot of women’s experiences and views, which may later have changed. However, this provides insight into the concerns women had during the first few months of the pandemic.

Our findings regarding VAW service experiences and fear in relationships should be considered within the context of how women were faring in other areas of life. Over half reported poorer wellbeing, access to health care, and access to informal supports. Thus, experiences of increased fear and barriers to VAW services may have been compounded with other layers of hardship, making life for some women exceptionally difficult. While this was not the experience of all women in the study, we recommend that the needs of those at highest risk of further harm drive future service models. Our findings clearly support the need for flexibility in VAW service delivery; this should include working with public health authorities to develop guidelines that can allow for in-person service options whenever possible.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has had significant impacts on women and their service use, it has also encouraged the use of existing technology and inspired new ways to support women (Emezue, 2020) and, at least in the short-term, has led to increased funding and attention to VAW around the world (Mintrom & True, 2022; UN Women, 2020). The disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic provides the opportunity for the VAW sector, and decision-makers more broadly, to implement innovative, survivor-centered service models.

References

Burnett, C., Ford-Gilboe, M., Berman, H., Ward-Griffin, C., & Wathen, N. (2015). A critical discourse analysis of provincial policies impacting shelter service delivery to women exposed to violence. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 16(1–2), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154415583123

Butler, N., Quigg, Z., Pearson, I., Yelgezekova, Z., Nihlén, A., Bellis, M. A., & Stöckl, H. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 and associated measures on health, police, and non-government organisation service utilisation related to violence against women and children. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12644-9

Carrington, K., Morley, C., Warren, S., Harris, B., Vitis, L., Ball, M. … Ryan, J. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on domestic and family violence services and clients: QUT Centre for Justice research report. QUT Centre for Justice. Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/206624/1/72848410.pdf

Emezue, C. (2020). Digital or digitally delivered responses to domestic and intimate partner violence during COVID-19. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(3), e19831. https://doi.org/10.2196/19831

Godin, M. (2020). How coronavirus is affecting victims of domestic violence. Time. https://time.com/5803887/coronavirus-domestic-violence-victims/

Gosangi, B., Park, H., Thomas, R., Gujrathi, R., Bay, C. P., Raja, A. S., & Khurana, B. (2021). Exacerbation of physical intimate partner violence during COVID-19 pandemic. Radiology, 298(1), E38–E45.

Graham-Harrison, E., Giuffida, A., & Smith, H. (2020). Lockdowns around the world bring rise in domestic violence. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/mar/28/lockdowns-world-rise-domestic-violence

Haag, H., Toccalino, D., Estrella, M. J., Moore, A., & Colantonio, A. (2022). The shadow pandemic: A qualitative exploration of the impacts of COVID-19 on service providers and women survivors of intimate partner violence and brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 37(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000751

Harris, R. M., Wathen, C. N., & Lynch, R. (2014). Assessing performance in shelters for abused women: Can ‘caring citizenship’ be measured in ‘value for money’ accountability regimes? International Journal of Public Administration, (37), 737–746. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2014.903273

Johnson, M. P., & Leone, J. M. (2005). The differential effects of intimate partner terrorism and situational couple violence: Findings from the national violence against women survey. Journal of Family Issues, 26(3), 322–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X04270345

Kourti, A., Stavridou, A., Panagouli, E., Psaltopoulou, T., Spiliopoulou, C., Tsolia, M., & Tsitsika, A. (2021). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211038690

Lapierre, S., Vincent, A., Brunet, M., Frenette, M., & Côté, I. (2022). ‘We have tried to remain warm despite the rules.’ Domestic violence and COVID-19: implications for shelters’ policies and practices. Journal of Gender-Based Violence. https://doi.org/10.1332/239868021X16432014139971

Lyons, M., & Brewer, G. (2021). Experiences of intimate partner violence during lockdown and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-021-00260-x

Mantler, T., Veenendaal, J., & Wathen, C. N. (2021). Exploring the use of Hotels as Alternative Housing by Domestic Violence Shelters During COVID-19. International Journal on Homelessness, 1(1), 32–49. https://doi.org/10.5206/ijoh.2021.1.13642

Maki, K. (2019). More than a bed: A national profile of VAW shelters and transition houses. Ottawa, ON: Women’s Shelters Canada. Retrieved from https://endvaw.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/More-Than-a-Bed-Exec-Summary.pdf

Mintrom, M., & True, J. (2022). COVID-19 as a policy window: Policy entrepreneurs responding to violence against women. Policy and Society, 41(1), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1093/polsoc/puab017

National Domestic Violence Hotline. (2020). Staying safe during COVID-19. Retrieved October 28, 2021, from https://www.thehotline.org/resources/staying-safe-during-covid-19/

Pentaraki, M., & Speake, J. (2020). Domestic violence in a COVID-19 context: Exploring emerging issues through a systematic analysis of the literature. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 8(10), 193-211. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2020.810013

Petersson, C. C., & Hansson, K. (2022). Social work responses to domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences and perspectives of professionals at women’s shelters in Sweden. Clinical Social Work Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-022-00833-3

Pfitzner, N., Fitz-Gibbon, K., & True, J. (2020). Responding to the ‘shadow pandemic’: Practitioner views on the nature of and responses to violence against women in Victoria, Australia during the COVID-19 restrictions. Retrieved from https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2020-06/apo-nid306064.pdf

Piquero, A. R., Jennings, W. G., Jemison, E., Kaukinen, C., & Knaul, F. M. (2021). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic - Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 74, 101806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2021.101806

Ravi, K. E., Rai, A., & Schrag, R. V. (2021). Survivors’ experiences of intimate partner violence and shelter utilization during COVID-19. Journal of Family Violence, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-021-00300-6

Stark, L., & Vahedi, L. (2021). Lessons from the past: Protecting women and girls from violence during COVID-19. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/lessons-from-the-past-protecting-women-and-girls-from-violence-during-covid-19-157609

Steacy, L., & Burr, A. (2021). COVID-19 restrictions can increase isolation, risk for victims of domestic violence: B.C. advocates. City News Vancouver. https://vancouver.citynews.ca/2021/12/28/bc-covid-restrictions-domestic-violence/

Taub, A. (2020). A new COVID-19 crisis: Domestic abuse rises worldwide. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/world/coronavirus-domestic-violence.html

Trudell, A. L., & Whitmore, E. (2020). Pandemic meets pandemic: Understanding the impacts of COVID-19 on gender-based violence services and survivors in Canada. Ending Violence Association of Canada & Anova. http://www.anovafuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Full-Report.pdf

United Nations. (2020). UN chief calls for domestic violence cease fire amid horrifying global surge. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1061052

UN Women. (2020). COVID-19 and ending violence against women and girls.https://www.unwomen.org/en/digitallibrary/publications/2020/04/issue-brief-covid-19-and-ending-violence-against-women-and-girls

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family planning and ending gender-based violence, female genital mutilation and child marriage. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/COVID-19_impact_brief_for_UNFPA_24_April_2020_1.pdf

Viero, A., Barbara, G., Montisci, M., Kustermann, K., & Cattaneo, C. (2021). Violence against women in the Covid-19 pandemic: A review of the literature and a call for shared strategies to tackle health and social emergencies. Forensic Science International, 319, 110650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110650

Wathen, C. N. (2020). Identifying intimate partner violence in mental health settings: There’s a better way than screening. Psynopsis: Canada’s Psychology Magazine, 42(2), 17–18. Canadian Psychological Association. https://cpa.ca/docs/File/Psynopsis/2020-Vol42-2/index.html

Women’s Aid Federation of England. (2021). What is coercive control? Retrieved October 25, 2021, from https://www.womensaid.org.uk/information-support/what-is-domestic-abuse/coercive-control/

Women’s Shelters Canada. (2020). Shelter voices 2020. http://endvaw.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Shelter-Voices-2020-2.pdf

Wood, L., Baumler, E., Schrag, R. V., Guillot-Wright, S., Hairston, D., Temple, J., & Torres, E. (2021). “Don’t know where to go for help”: Safety and economic needs among violence survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00240-7

World Health Organization. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health impacts of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564625.

World Health Organization. (2020). Addressing violence against children, women and older people during the COVID-19 pandemic: Key actions. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Violence_actions-2020.1

Acknowledgements

This study was part of a larger project that sought to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on various aspects of the VAW sector, including changes in services, changes to physical space, and impacts on clients and staff. We sincerely thank all of the agencies in Ontario, Canada who worked in partnership with us to make this research possible. Service partners include: Anova in London, Women’s Rural Resource Centre in Strathroy, Optimism Place in Stratford, Women’s Interval Home of Sarnia-Lambton, Faye Peterson House in Thunder Bay, and all agencies who participated in the recruitment of participants for this study. In addition to the listed authors for this paper, we thank the following for their contributions: Drs. Eugenia Canas, Marilyn Ford-Gilboe, and Vicky Smye. For more information about the VAW Services in a Pandemic project, visit: https://gtvincubator.uwo.ca/vawservicespandemic/.

Funding

The study was funded by a Western University Catalyst Grant: Surviving Pandemics, and knowledge mobilization activities were funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) Connection Grant. Wathen is funded by a SSHRC Canada Research Chair in Mobilizing Knowledge on Gender-Based Violence.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

MacGregor, J.C.D., Burd, C., Mantler, T. et al. Experiences of Women Accessing Violence Against Women Outreach Services in Canada During the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Brief Report. J Fam Viol 38, 997–1005 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00398-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00398-2