Abstract

Purpose

Schools can be an arena for age appropriate and objective information about the support families can get from the child protection services (CPS). There is reason to believe that many children have misconceptions about the CPS and are afraid to talk to the social workers who investigates if there is reason to be concerned about a child’s well-being. The aim of the study was to investigate the prevalence of misconceptions about child protection services (CPS) among school children in Norway.

Method

A questionnaire containing 10 statements that measure children’s misconceptions and attitudes about the CPS was developed and distributed to 215 children aged 11–15 years old (M = 12.2 years).

Results

The results showed that 10.7% of the sample have a misconception about children being removed from their homes by CPS and that 17% of the sample had a negative perception of the CPS in general.

Discussion

The child might wrongfully get the impression that it is at risk of being removed from the parents. Participation in assessment and planning may be challenging for a child under such conditions. Therefore, it is important that adults who work with children are aware that these misconceptions are quite common, also among youth.

Implications

The prevalence of misconceptions about CPS among children in the general population as well as those in contact with CPS indicate a need for age-appropriate information. If such misconceptions are prevented it might be easier for children to reach out for help if they or somebody they know, are subject to abuse or neglect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

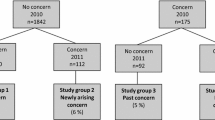

In previous studies of child protection services and children’s participation (Vis, 2012), the aim has been to identify barriers toward children’s participation. One emerging barrier was that the children contacted by child protection services (CPS) often did not want to talk to social workers because they were afraid of being placed in care. Furthermore, it was discovered that children may have misconceptions about the purpose of CPS investigations and the types of services that are offered. These findings were mainly based upon social workers experiences from contact with children when they were processing referrals or carrying out investigations and assessments. Little is however known about perceptions about the CPS among the general population of children.

The aim of the current study was to investigate the prevalence of misconceptions about the CPS among Norwegian school children. This is of interest because it is important to be aware of misconceptions children might have so that they can be addressed at an early stage. Doing so might increase the ability and opportunity children have, to participate in the processing of their case.

Background

Children and families that have been involved in a child protection process often find the experience to be very difficult, and they are likely to view involvement from the child protection services as intimidating and stressful (Buckley et al., 2011). This may be due to preconceived attitudes about the child protection services as an agency that interrupts the family life and removes children from their biological families. Additionally, child protection services are subject to scrutiny and criticism in the public debate. The way that child protection cases are presented in the media can be unbalanced and may create a false image that CPS mainly focuses on removing children from home. In reality, the picture is much more nuanced. In 2016, about 4.1% (N=46 950) of all children (0-17 years) in Norway were subject of a child protection investigation. About one third of these cases resulted in either delivery of homebased assistance (32.9%, N=15 451) or out of home care (0.6%, N=318). This indicates that although a large number of children will be in contact with CPS at one time during their childhood, the likelihood of being placed in out of home care is very small.

During the recent years, several initiatives have been taken to raise children’s awareness about the purpose and working methods of CPS in Norway (Ministry of Children and Equality, 2008). These initiatives include information campaigns at schools for which pamphlets and animated videos have been developed. The videos have also been shown on national television. The main aims for the information campaign were to (i) inform children that there is a CPS, (ii) inform children why there is a CPS (iii) inform children about how to get in contact with CPS. The effects of this communication strategy have to date not been evaluated.

Children and young people are influenced by information from different sources. This may be official information issued by the government through pamphlets and information campaigns at schools, it may be from portraits of CPS through news and media or it may be information by tales from friends or family. In the news media CPS is often portrayed negatively. Studies that have analysed the content of all CPS related news coverage in major Norwegian newspapers found that the proportion of negative portraits’ of CPS were 54% in 2005 (Stang, 2007) and 40% in 2010 (Føleide 2011). Although we are not aware of any studies that support this claim, we assume that the CPS also is subject to considerable amounts of negative attention in social media.

There has been a shift in the way young people use the media and the types of media that inform children about current events. The use of internet as a primary news information source have tripled during the last decade. In Norway only 27% of children aged 9–16 watch news on television, 37% read news online and 9% read news on paper (The Norwegian Media Authority, 2016). From the age 11 and up, the use of social media increases.

Children’s rights are taught in schools in Norway as part of the curriculum. One study found that about 79% of Norwegian school children had heard about children’s rights at school, 42% had read about it on the internet, 41% had information from tv/radio and about 40% had discussed it at home (Unicef, 2010). The study did however find that 45.7% of school children aged 12–16 years in the Nordic countries (Unicef, 2010) knew little or nothing about children’s rights. It is therefore not clear that school curriculum effectively impacts children’s perceptions about their rights more generally.

Ipsos Public Affairs (2015) carried out an interview survey that aimed to identify how the CPS is viewed among the public. Participants were a representative selection from the general population of youth and adults above the age of 15. years (N = 1012). The results showed that 7% had a very good impression of the CPS, and 28% had a good impression. 5% had a very bad impression, and 10% had a somewhat bad impression. About 35% were neutral and 15% did not know.

Literature Review

A search for relevant research literature regarding children’s perspectives on child protection services was carried out on 22 of January 2022, using the Social Care Online database (SCIE). The search was restricted to the time period 2012 to 2022 and a combination of keywords were used. These included the terms: child protection and children’s perspective, combined with either perspective, scared, angry, misunderstanding or perception. The search yielded 2545 hits. All studies were screened by title. Then we assessed the abstracts of potentially relevant studies. We found two recent studies that were meta-syntheses of the research literature. The first aimed to identify family members’ perspectives of CPS (Bekaert, et al., 2021). Three main themes were identified: (i) family members’ perception of the system (ii) family members’ perception of how they were viewed by the social-worker and (iii) how the family viewed the social-worker. In terms of family members’ perceptions of the CPS it was evident that most of the research had focused on parents and perceptions. Out of 35 studies included in the meta-synthesis by Becaert et al., only 14 had children as research subjects, and all were qualitative studies. The authors concluded that there was an overriding negative experience by all family members from having social care involvement. Children’s experiences with CPS as a system were mainly related to negative feelings associated with the termination of contact due to CPS organization and turnover of workers (Curry, 2019; Strolin-Goltzman et al., 2010). It should be noted though that these were all studies of children who was or had been in contact with the CPS system. These results cannot therefore easily be generalized to the general population of children.

The second meta-synthesis looked at children’s and caregivers’ perspectives about mandatory reporting of child maltreatment (McTavish et al., 2019). Their systematic review identified 35 articles that represented the views of altogether 821 caregivers, 50 adults with a previous history of child maltreatment and 28 children. Children’s perspectives were mainly related to fears about being reported and fear of CPS responses to reports. Parents’ fears of being involved with CPS were described by caregivers as a reason to avoid services and as a reason to not disclose important information to mandated reporters. The authors concluded that across all the studies some common recommendations from researchers could be identified. These were mainly that responding to reports of maltreatment CPS should attempt to minimize fear inducing service responses by listening to their fears and concerns and provide appropriate information about CPS responses and the limits of confidentiality.

It seems clear from the syntheses of altogether 70 articles in these two studies by Becaert et al. (2021) and by McTavish et al. (2019) that the evidence of how children in the general population perceive CPS is almost non-existent. Virtually all the previous research has focused on children and parents who are already in contact with services.

Despite of the distress that is often associated with CPS involvement, it is also widely recognized that child participation may have several benefits for the quality of case assessments and decision making. A research review (Author 1) found that when children participate in the assessment process it may lead to identification of other types of problems and resources than the issues the adults are already aware of. Additionally, participation in the decision-making process may have the potential beneficial effect that interventions become better tailored toward the child’s needs. Child participation is also a children’s rights issue that is rooted in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and is required by law in Norway and many other countries.

In 2012 an interview study was carried out among children and families that had received support services from the CPS (N=25) (Haugen, Paulsen & Berg, 2012). Findings indicated that parents and children were surprised by the extent of support services that were available, and that this was contrary to their beliefs that the CPS primarily was concerned with out-of-home placement of children. Parents and children identified a need for more readily available information about CPS and recognized that their impressions had been influenced by negative portraits of CPS in media.

A Swedish study (Jernbro, Otterman, Lucas, Tindberg & Janson, 2017) examined the disclosure of child physical abuse among children aged 14–15 years (N=3198). They found that only 52% of the children that had experienced physical abuse had disclosed it to anybody and that adolescents often first disclose abuse to peers, (37.5%), i.e., siblings, friends, or boy/girlfriends. This underscores the importance of informing children about when and how it is appropriate to report abuse to professionals such as teachers or to CPS. If there are highly prevalent perceptions among children and adolescents that hinder such reporting this should be addressed.

The aim of this study is therefore (i) to identify the extent of misconceptions about CPS among 11- and 15-year old school children, (ii) to look at associations between children’s conceptions about the CPS, and the types of sources children have information about the CPS from, and finally (iiI) to identify the impact of age and gender upon school children’s perception of CPS.

Method

The study was designed as a cross sectional questionnaire study.

Sampling

The participants were children recruited from seven different schools in Norway. We recruited trough schools to obtain a good response rate. Criteria for the sampling of schools were that both city schools and schools in rural areas should be represented. Because we were dependent upon cooperation from the schools to distribute and collect the questionnaire during school time, the schools were sampled by convenience. We asked schools within the major city in one region of Norway and rural schools in order of geographical proximity to that city, until the desired sample size was obtained. The schools are assumed to be representative of schools with that region but may differ in some aspects from schools in other parts of the country. Most notably, no metropolitan area schools were represented. The questionnaire was given to the children in their classroom by their teacher. Consent to participate was collected from parents and the children. A total of 215 children were asked to participate and 204 consented. The response rate was 94.8%.

The majority (69%) of the respondents were 5th grade students (N=141) and the rest were 9th grade students (N=63). There were 50.9% girls (N=104) and the mean age was 12.2 years.

Measures

Perceptions About the CPS

In order to measure children’s perceptions about the CPS, we developed a questionnaire specifically for this study. First, we interviewed three experienced social workers about the types of misconceptions they had encountered in their contact with children while processing CPS cases (Berger, 2017). The interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis (Richie & Lewis, 2003) and resulted in the grouping of social-worker responses into two main categories. The two categories were (i) that some children believe contact with CPS means that they will be removed from home and placed into care and (ii) that some children are afraid of CPS. In order to measure these types of misconceptions as latent constructs, ten statements, five for each construct were created. The children were asked to rate how they agreed to those statements on a five-point Likert scale. The scale vas labeled 1=‘totally disaggree’, 2=‘somewhat disagree’ ,3= ‘neither disagree nor agree’, 4=‘somewhat agree’ and 5=‘totally agree’. These ten statements were included in the questionnaire as the ‘Removal From Home’ scale and ‘Afraid of the CPS’ scale.

Removal from Home Scale

Misconceptions about Removal from home were measured by the statements; (i) ‘CPS kidnap children, (ii)‘ CPS steal children from their parents’, (iii)‘parents must protect their children from being taken by CPS’ (iv) ‘CPS remove children for no good reason’ and (v) ‘CPS take children away’. The words kidnap, steal and take were used because those were specifically mentioned in the social worker interviews. A high score on this scale indicate that the child did agree to common misconceptions about children being placed in out of home care. Chronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.77.

Afraid of the CPS Scale

The perception that children were “Afraid of CPS” was measured by the statements (i) The CPS is dangerous, (ii) The CPS is scary, (iii) children are afraid of the CPS, (iv) CPS is good and (v) social workers in the CPS are nice. A high score on the Afraid of CPS scale indicate that children have negative preconceptions about CPS. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.82.

Sources of Information

Information was collected about the types of sources children based their information on. These included parents, friends, teachers, CPS and media. For each of these the child rated on a scale from 1 to 5 to how much they had heard about CPS. On this scale the labels were; 1=nothing, 2=little, 3= some, 4=much, 5=very much.

Demographics

Age and gender were included as demographic variables.

Statistical Analyses

First, we calculated a mean score for each scale after the coding was reversed for certain items so that all indicators point in the same direction.

Then we conducted a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test differences in children’s misconceptions about the CPS by age and gender. We calculated effect sizes as Cohen’s d. We also tested for interaction between age and gender. We tested for significant correlations between misconceptions about CPS and the different information sources.

Results

The Extent of Misconceptions About the CPS Among Children

About 10% of the children believed that the CPS kidnap, steal or take children away from their parents without good reason. About 15% of the children thought the CPS is scary and about 25% believed that children in general are afraid of the CPS. Children’s responses to the ten items that were used as indicators of misconceptions about CPS are shown in Table 1.

The mean score for the Removal From Home scale was 1.87 (SD=0.86) and the mean score for the Afraid of the CPS scale was 1.85 (SD=0.68). In total, 10.7% of the children scored above three on the Removal From Home scale indicating they agree to common misconceptions about the CPS’s removal of children from their parents. For the Afraid of the CPS scale 17.1% of the children scored above three, which show that they agreed to statements that indicated they were afraid of the CPS. There was a strong correlation between the Removal from Home scale and the Afraid of the CPS scale (r=0.72, p<0.01). This showed that the two latent variables were strongly related, presumably because false beliefs that the CPS take children away from their homes cause children to be afraid of the CPS.

Types of Sources Children have Information About CPS From

Relationships between scores on the Removal From Home, Afraid of the CPS scales and sources of information is shown in Table 2. For the children in the study, parents were the most common source of information about the CPS, followed by teachers. The children less frequently got information from the mainstream media about the CPS from a social worker or the CPS agency. There was a significant correlation between the amount of information children had from their parents and misconceptions about removal from home, but the effect was small (r=0.15, p<0.05). This indicates that overall, there were no strong relationships between where children learned about the CPS and their misconceptions about removal from home or how scared they were for the CPS. We did however find that child age was associated with children’s sources of information about the CPS. Older school children were significantly more informed by friends, teachers and CPS services than were younger children. However, the associations were quite weak with correlation estimates around 0.2.

The Impact of Age and Gender Upon School Children’s Perception of the CPS

Differences in mean scores among girls and boys and between 5th graders (10-year-olds) and 9th graders (14-year-olds) are shown in Table 3. The results show that misconceptions about removal from home are significantly more prevalent among older children. The effect size was medium (d=0.70). Boys more often reported misconceptions about removal from home compared to girls but when age is controlled for this difference was not significant. Boys scored significantly higher on the Afraid of the CPS scale compared to girls when age was controlled for. The gender effect was however small (d=0.35). Although gender differences were more pronounced among the 10-year-old children than among the 14-year-old children, there were no significant interaction between age and gender.

Discussion

We set out to identify to what extent children subscribe to misconceptions about removal from home and to what extent Norwegian school children are scared of the child protection services. The results showed that 10.7% of the children agreed to the false beliefs statements, and hence may have a misconception about children being removed from their homes by the CPS. This means that just over one in ten school children in our sample believed that the CPS is an agency that steals, kidnaps, or takes children for no reason. Although the number is not extremely high, there is still a considerable proportion of children who believe that this is the case. Previous studies have found that these are common misconceptions among children who have been reported to the CPS (McTavish et al., 2019) and by children in contact with CPS. Bekaert and colleagues (2021) found that it is common for children who are already in contact with CPS to be scared of CPS and to have false beliefs. However, because their meta-synthesis was based upon qualitative studies they were not able to establish a specific proportion of children in contact with CPS that have false beliefs. We question to what degree the negative impressions and false beliefs were present before the child came in contact with the CPS and in what proportion of cases these beliefs were created or enhanced by the CPS. We cannot answer this question based upon the data from this current study but at least we were able to identify that such beliefs are quite limited among the general population of children.

As the Norwegian Child Welfare Act Sects. 4–12 emphasizes, there are requirements that must be met in order for a child to be removed from its home. There must be compelling reasons for placing a child in foster care, such as serious neglect or abuse (The Child Welfare Act). Through both the media and anti-CPS groups on social media, it is possible that children and young people have got the impression that CPS has removed children from their homes for no reason (Stand, 2007; Føleide, 2011). As 10.7% of the sample stated that they believe that CPS moves children for no reason, this indicates that more information is needed about why some children have to move away from their parents. This conclusion is supported by the findings from Haugen, Paulsen and Berg (2012 which indicated that children were surprised by the extent of support services that were available once such information is given. Perhaps the CPS themselves should do more in the initial phase of case processing in order to prevent any misunderstanding among the children.

Objective information about CPS is however difficult to convey because there will always be conflicts of interest between parents who have been accused of child abuse and neglect and the CPS. Therefore, conceptions about CPS will continue to be influenced by parents, media and social media and there may be a discrepancy between the CPS version of the story and the story of e.g., families that have lost the custody of their children. It is conceivable that children and young people are less critical of what they read and do not consider the source or origin of the information. If children think that CPS is someone who kidnaps or steals children, it can be frightening if the mother or father are to receive support from CPS. The child might wrongfully get the impression that it is at risk of being removed from the parents. Being ready for participation and supporting interventions may be challenging for a child under such conditions (Bekaert, et al., 2021). Hence, it is important that adults who work with children are aware that these misconceptions are quite common, also among youth. In order to avoid or reduce this misconception, there are two arenas that are paramount: CPS itself and schools. First, it could help if CPS develops age relevant information material that can provide children with basic knowledge of why CPS in some cases must move children. Additionally, the child’s preconceptions about CPS should be a topic at the early stage of a child consultation, meaning that the social worker should address the issue early in a CPS investigation. Asking questions like “What do you know about CPS?” and “Why do you think that I want to talk to you today?” may be helpful in eliciting a conversation about this topic. This is a recommended procedure in child forensic interviewing (Lamb, Orbach, Hershkowitz, Esplin, & Horowitz 2007).

Reducing barriers should however be considered paramount in all types of participatory work in child protection, not only in forensic settings.

The other important arena where this issue could be addressed is in schools. We believe the teachers could play an important role of providing school children with reliable and objective information about the CPS. We know from previous studies that children who receive support or interventions from CPS have a significantly higher proportion of risk-factors for a negative development and school dropout compared to their peers, and there is a clear association between risk factors experienced more often by children in CPS and their academic achievement (Kirkøen, Engell, Andersen, & Hagen, 2019). These children also have an increased risk of later marginalization (Kirkøen et al., 2019). By reducing the misconceptions about CPS, teachers can contribute to lowering the threshold for children in the CPS to cooperate and receive support from CPS. This may subsequently reduce some of the stress these children experience in these cases and may contribute to a better situation within the school setting. Having accurate information about CPS is however important for all school children, not only those who receive interventions from CPS. Especially in the current “zeitgeist” where fake news and alternative facts are serious threats to the validity of the general knowledge in the society, having access to reliable and objective information becomes even more eminent.

The results also showed that 17% of the sample had a negative perception of CPS in general. A negative perception of CPS can be explained on the basis of several factors. First, parents’ attitudes can be transferred to their child (Martin et al., 2010). In this sample, 25% perceive the parents’ attitude towards the child welfare service as negative, which may therefore explain why 17% of the sample themselves have a negative perception of the child welfare service. It is probable that the parents’ attitudes towards the child welfare service have influenced the children’s perception of the service (Bekaert, et al., 2021). Secondly, children are affected by the media and the internet. An explanation may be that children read about CPS in the media, watch something on TV or read about the CPS on the internet. TV and the internet are both examples of mass media that children use that have a great influence (Waldahl, 1999). Previous studies have shown that cases about child protection in the media often are negatively charged (Føleide, 2011; Stang, 2007). If this is a child’s only source of information about child protection, negatively charged cases about child welfare in the media can contribute to influencing children’s perception of CPS as something negative. A third explanation for the fact that a large part of the sample has a negative perception of child protection in general may be that they have a lack of knowledge about what child protection actually encompasses. Lack of knowledge can lead to children gaining an opinion based on what they hear others say, or what they see in the media, without knowing what CPS do to support and assist families when needed. There is no fast and easy fix for this problem. The media play an important role of exposing CPS case stories where wrongdoing is the case, which causes serious consequences for the families involved. However, the media tends to have solely a negative focus when addressing CPS issues, which may contribute to an unbalanced view of the services in the general population. Due to confidentiality issues, CPS are in most such cases limited from contradicting client statements or providing additional information in such a way that a fair and balanced portrait of CPS case processing is possible. Still, it is unfortunate that many children express fear and negative emotions towards the CPS because this may significantly reduce the likelihood that they will report any experience with abuse or neglect to an adult. As shown by Jernbro and colleagues (Jernbro, Otterman, Lucas, Tindberg & Janson, 2017) about one third of children aged 11–15 years who disclose beeing abused, disclose it to a peer. It is there for important that informtion about CPS is not only targetet at the population of children that are in contatct or are about to become in contact with CPS. One way to disseminate such information could be to include topics such as “what is CPS and how does it work?” and “what do you do if you or your friend is being abused or neglected?” as a topic in the social science or life skills curriculums at school.

Girls have a more positive perception of CPS in general than boys. This is a result that may be related to the fact that girls tend to talk more about emotions than boys (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). They are also socialized to talk more about the emotional side of an event than boys do. Research has shown that parents talk more about the emotional side of an event with their daughters than with their sons (Harwood et al., 2008). It is conceivable that parents have talked more with their daughters than their sons about child protection issues and this may be an explanation for why one sees this difference between boys and girls in the sample. By increasing the knowledge about the child protection service and how CPS carries out its mission in school settings, the perception can become more positive. Previous research has showed that girls exhibit more prosocial behavior than boys do. Girls are more helpful, cooperative and they understand other people’s feelings more easily than boys (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). These differences may help to explain why girls perceived CPS more positively than boys.

In terms of age, the results showed that the 5th grade participants perceived parents’ attitudes towards CPS as more positive than the 9th grade participants. It is therefore conceivable that the 5th grade participants are more influenced by the parents than the 9th grade participants. Because the 9th grade participants are older, they may not be affected to the same degree by, for example, parents’ attitudes, but form their own opinions based on what they read or experience. Another explanation may be that 9th grade students follow more closely what is happening in the media. That way, they may have heard more about the cases where CPS have placed children in foster care. As the media often only shows one side of the issue, the participants may base their knowledge on this (Føleide, 2011; Stang, 2007). Furthermore, the participants from 9th grade are old enough to be on Facebook. On Facebook, there are anti-child protection groups that are open to everyone. On these pages, adults write about how CPS kidnaps children, and that CPS must be stopped. In particular is it likely that when a parent posts and likes negative CPS stories or “news” such stories will also be visible in their children’s feed. It is possible that the social media echo chamber effect may reinforce the likelihood that parents’ attitudes will influence their children. As 5th grade participants are too young to have Facebook, this may be a possible explanation for why 9th grade participants to a greater extent than 5th grade participants believe that the CPS steal, kidnap or just take children.

Limitations

The differences between boys and girls could also be explained by other variables that were not included in this study, e.g., social class, cognitive functioning, socio-economic status and academic level at school. We do not know if any of the children who participated in the study had current or previous experiences from contact with CPS. It is likely that responses from those with CPS experience is affected, positively or negatively, by this experience. With a sample size of n=201 we are limited to discovering standardized differences of about 0.4 and above with statistical power of 0.8. The instrument was designed for this study and had not been previously tested. Although the scales did show acceptable internal consistency with this sample, it is possible that this could be improved by refining the instrument further. The lack of demographic information about the children and their families makes it difficult to establish how representative they are for the overall population of children. There might be a sample bias that we are not aware of.

Implications for Practice

The prevalence of misconceptions about CPS among children in the general population as well as those in contact with CPS indicate a need for age-appropriate information at several levels. More information targeted at the general population of children can help reduce stress and fear associated with being reported to CPS (McTavish et al., 2019) and receiving services (Bekaert, et al., 2021). If such misconceptions are prevented it might be easier for children to reach out for help if they or somebody they know, are subject to abuse or neglect. We recommend that information about CPS is included as part of social studies or life skills curriculums in schools. Perhaps this could be incorporated within a broader context of human rights and health and safety awareness.

It is however not likely that all types of misconceptions can be avoided for every child. The CPS needs to be aware of this and should assume that when a child is reported, he or she may be anxious of what can happen. This should be addressed in conversations between a social worker and the child as early as possible. If an alliance of trust can be established between the parent, the child and the social worker it is more likely that the child will be able to participate in a manner that may help improve the quality of assessment and service delivery.

There are still significant knowledge gaps that could be addressed in future research. Chief among these is what the effects of more targeted information about CPS might be and how CPS should address preconceptions leading to alienation and fear among children in their processing of cases.

Conclusions

This study examined Norwegian school children’s perceptions of the Norwegian Child Protection Services. The purpose of the study was to examine children’s perceptions of various factors related to child protection, and the extent to which there were gender differences or differences between age groups. The results showed that one in ten children had a misconception about the CPS kidnapping children from their parents, and a relatively high proportion had a negative perception of CPS in general. If children and young people do not have sufficient or correct knowledge of CPS, it could lead to a lack of trust in the service. It is also likely that children and young people with a misconception of CPS may be afraid of the CPS. By increasing knowledge and improving the perception of the service, it is possible that user cooperation and participation also may be improved. School teachers may play an important role of providing children with reliable information about CPS. We believe that including education about the role of the CPS may contribute to children being less scared of CPS.

References

Bekaert, S., Paavilainen, E., Scheke, H., Baldacchino, A., Jouet, E., Zablocka-Zytka, L. … Appleton, J. V. (2021). Family members’ perspectives of child protection services, a metasynthesis of the literature. Children and Youth Services Review, 106094

Berger, T. F. (2017). Barns oppfattelse av det norske barnevernet. En sp?rreunders?kelse blant norske 5.-og 9.klasseelever [Childrens perception of child protection services]. Troms?.(Master's thesis, UiT Norges arktiske universitet)

Buckley, H., Carr, N., & Whelan, S. (2011). ‘Like walking on eggshells’: service user views and expectations of the child protection system. Child & Family Social Work, 16, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2010.00718.x

Curry, A. (2019). “If you can’t be with this client for some years, don’t do it”: Exploring the emotional and relational effects of turnover on youth in the child welfare system. Children and youth services review, 99, 374–385

Føleide, S. (2011). Towards a more balanced debate about the CPS? [Mot ein meir reflektert barnevernsdebatt? Ei innhaldsanalyse av barnevernframstillingar i VG og Dagbladet]. Master thesis, University of Oslo

Harwood, R. L., Miller, S. A., & Vasta, R. (2008). Child psychology: development in a changing society (5 utg.). Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons

Lamb, M. E., Orbach, Y., Hershkowitz, I., Esplin, P. W., & Horowitz, D. (2007). A structured forensic interview protocol improves the quality and informativeness of investigative interviews with children: a review of research using the NICHD Investigative Interview Protocol. Child abuse & neglect, 31(11–12), 1201–1231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.03.021

Haugen, G. M. D., Paulsen, V., & Berg, B. (2012). Parental and child experience from the Child Protection Services in Trondheim [Foreldre og barns erfaringer i møte med barneverntjenesten i Trondheim kommune]. Trondheim: NTNU Samfunnsforskning

Ipsos Public Affairs (2015). Investigation about the Norwegian Child Protection Services [Undersøkelse om barnevernet utarbeidet for barne-, ungdoms- og familiedirektoratet]. Downloaded from: https://www.bufdir.no/global/nbbf/Barnevern/Undersokelse_om_barnevernet.pdf

Jernbro, C., Otterman, G., Lucas, S., Tindberg, Y., & Janson, S. (2017). Disclosure of Child Physical Abuse and Perceived Adult Support among Swedish Adolescents. Child Abuse Review. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2443

Kirkøen, B., Engell, T., Andersen, A., & Hagen, K. A. (2019). Barn i barnevernet og skolefaglig utvikling [Children in the CPS and school development]. Norges Barnevern, 96 (04/2019)

Martin, G. N., Carlson, N. R., & Buskist, W. (2010). Psychology (4 utg.). Harlow: Allyn & Bacon

The Norwegian Media Authority [Medietilsynet]. (2016). Children and the Media. [Barn og medier]. Dowloaded from: http://www.barnogmedier2016.no/page-19

McTavish, J. R., Kimber, M., Devries, K., Colombini, M., MacGregor, J. C., Wathen, N., & MacMillan, H. L. (2019). Children’s and caregivers’ perspectives about mandatory reporting of child maltreatment: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. British Medical Journal open, 9(4), e025741

Ministry of Children and Equality [Barne-, og likestillingsdepartementet]. (2008). An open child protection service—communication strategy for the CPS 2008–2011. [Et åpent barnevern—kommunikasjonsstrategi for barnevernet 2008–2011]. Retrieved from: https://www.bufdir.no/global/Et_apent_barnevern_kommunikasjonsstrategi_2008_2011.pdf

Nsd. (2017). Information and Consent. [Informasjon og samtykke]. Downloaded from: http://www.nsd.uib.no/personvernombud/hjelp/informasjon_samtykke/

Richie, J., & Lewis, J. (2003). Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. Sage Publications

Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). A Review of Sex Differences in Peer Relationship Processes: Potential Trade-Offs for the Emotional and Behavioral Development of Girls and Boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 98–131

Stang, E. (2007). Prtrayals of the CPS in the media: A content analysis [Fremstillinger av barnevern i løssalgspressen: en innholdsanalyse av artikler om barnevern i VG og Dagbladet]. Oslo: Centre for Welfare and Labour Research [Norsk institutt for forskning om oppvekst, velferd og aldring]

Strolin-Goltzman, J., Kollar, S., & Trinkle, J. (2010). Listening to the voices of children in foster care: Youths speak out about child welfare workforce turnover and selection. Social work, 55(1), 47–53

The Child welfare Act. (1992). Downloaded from: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/049114cce0254e56b7017637e04ddf88/the-norwegian-child-welfare-act.pdf

Unicef. (2010). Nordic study on Child Rights to participate 2009–2010

Vis, S. A., Holtan, A., … Thomas, N. (2012). Obstacles for child participation in care and protection cases?why Norwegian social workers find it difficult. Child abuse review, 21(1), 7–23.

Waldahl, R. (1999). Media Influence [Mediepåvirkning] (2 utg.). Oslo: Gyldendal

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the schools, teachers and school children who participated in our study.

Funding

The study was funded by the Regional Centre for Child and Youth Mental Health & Child Welfare, UiT-Arctic University of Norway. Open Access funding provided by UiT The Arctic University of Norway

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

The project was approved by the Data Protection Official in Norway, at the Norwegian Center for research Data (NSD). The survey was completed anonymously. Information about the study was disseminated to the parents, and written consent was obtained. It is possible that a survey about the CPS could have a negative impact on children who have been in contact with CPS. By providing the parents with sufficient information about the study, they could make an informed decision about whether their children should participate in the survey. If any of the parents thought that participating in such a survey could have negative consequences for their children, it is conceivable that they would not allow the child to participate in the survey.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vis, S.A., Berger, T. & Lauritzen, C. Norwegian School Children’s Perceptions of the Child Protection Services. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 39, 337–346 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-022-00822-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-022-00822-y