Abstract

Gender differences in school are often discussed in reference to a particular type of masculinity, negative masculinity, which is often conceptualized as detrimental to success. Another type of masculinity, instrumentality, has rarely been studied in schools even though instrumental characteristics are often exalted outside the academic context. The current study focuses on potential benefits that students may reap from instrumentality. The extent to which an instrumental self-concept is directly and indirectly associated with achievement motivation and self-esteem was examined for adolescent boys and girls in a structural equation model (SEM). A sample of German ninth graders (N = 355) completed self-report measures pertaining to their gender role self-concept, hope for success, fear of failure, and global and academic contingent self-esteem. The SEM revealed that instrumentality was associated with lower fear of failure and higher hope for success for both male and female adolescents. High scores in instrumentality were associated with greater self-esteem and lower academic contingent self-esteem. The association between instrumentality and global self-esteem was stronger for adolescent girls, and the indirect association between instrumentality and fear of failure through global self-esteem was significant only for girls. Results indicate that instrumentality can be an asset for students and that female students especially reap the benefits of an instrumental self-concept. The results are discussed in reference to the dangers of emphasizing solely the association between negative masculinity and academic failure, and the importance of studying relations with gender role self-concept separately for male and female adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

School represents a meaningful period in the lives of adolescents, yet there are significant gender disparities in how students fare in school, with adolescent boys displaying worse outcomes than girls (Van Hek et al., 2018; Voyer & Voyer, 2014). Some educational researchers have focused on gender and gender role self-concepts as a possible root for these outcomes. Investigations into how masculinities may be interacting with the demands of school have focused mainly on how negative aspects of masculinity are associated with detrimental outcomes (Lyng, 2009). However, the generalization that a masculine self-concept itself does not fit school requirements (cf. Kessels et al., 2014) seems premature. The present study investigates whether one dimension of masculinity—instrumentality—relates to possible positive outcomes in students. These outcomes comprise constructs relating to self-esteem and motivation, and their relation will also be investigated more closely as part of the present study. In addition, we will examine whether the relations between instrumentality and achievement motivation and self-esteem differ for male and female students. This will expand the current understanding of how the endorsement of gendered traits might have different implications for different gender groups. Overall, the present research investigates whether displaying traits traditionally associated with masculinity—namely, instrumental traits—can be an asset in school and whether these effects differ across gender.

Gender Role Self-Concepts

We employ the term gender to refer to social groups of men and women or boys and girls, acknowledging the social construct of gender as different from biological sex (American Psychological Association, 2020). In researching gender stereotypes (i.e., the culturally shared characteristics ascribed to men and women based on their gender membership; Myers et al., 2010, p. 467), studies have shown that people perceive agency, which includes traits such as ambition, confidence, and courage, to be more characteristic of men. Additionally, people perceive communion, which includes traits such as sensitivity and patience, to be more characteristic of women (Eagly et al., 2020). Other constructs described as masculinity and femininity respectively are instrumentality, which refers to action and self-confidence (Spence & Helmreich, 1980), and expressiveness (Spence et al., 1974), which refers to an awareness of the emotions of others and kindness (Korlat et al., 2021; Spence & Helmreich, 1980). Such descriptors can be used to capture both impressions of others and groups as a whole, as in research on gender stereotypes, but can also be related to how one perceives oneself, in the form of attribute self-perceptions (Tobin et al., 2010). When referring to self-attributions of traits traditionally associated with masculinity and femininity, the term gender role self-concept is often used.

In order to assess different dimensions of these gender role self-concepts, scales measuring instrumentality and expressiveness (Spence et al., 1974), agency and communion (Abele & Wojciszke, 2014; Bakan, 1966), or more generally masculinity and femininity (Bem, 1974, 1981), respectively, are widely used in research. Usually, these instruments are constructed by asking research participants how desirable (Bem, 1974) or typical (Spence & Helmreich, 1980) the given traits are for a man or a woman (or for an adolescent boy or girl, respectively [Kessels, 2005; Krahé et al., 2007]).

The content of what is deemed feminine and masculine is fluid across time (Eagly et al., 2020). Especially with regard to masculinity, theorists have criticized the trait approach as inadequately portraying masculinity as a “fixed character type” (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005, p. 847). Much literature has emphasised that masculine gender roles interact with “social, cultural, and contextual norms” (American Psychological Association Boys and Men Guidelines Group, 2018, p. 6). Several researchers recognize that multiple “masculinities” can be experienced in different ways depending on ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religion, and a host of other social group memberships (Smiler, 2004; Thompson et al., 1992). While we acknowledge the existing theoretical conceptions on masculinities, our psychological research focuses explicitly on the impact of gendered attribute self-perceptions, as measured by endorsement of instrumental traits, for both male and female students. Throughout the paper, we use the terms employed by the original researchers (e.g., instrumentality, agency, or masculinity) when describing earlier research results.

Masculinities in School

As introduced above, disparities in school performance have been analyzed with regard to gender. The feminization of school hypothesis emerged as one explanation for the academic underachievement of boys. It broadly refers to both the overrepresentation of female staff in school (Verniers et al., 2016) and the overall association of school with femininity (Heyder & Kessels, 2013). Studies showed that students perceive school and learning as something feminine (Heyder & Kessels, 2013; Jackson & Dempster, 2009). Indeed, male adolescents can actually increase their ascribed masculinity by not engaging at school or by being disruptive (Heyder & Kessels, 2017; Kessels & Heyder, 2020). Researchers have even posited that misconduct in school was closely tied to “enactment of masculinity in adolescence” (Heyder et al., 2021, p. 70). As such, the perceived feminization of school may lead boys to perceive a general incongruence between their own gender and academic engagement (Kessels et al., 2014; Verniers et al., 2016).

The lower fit between “male and masculine” (Heyder & Kessels, 2015, p. 467) and school is not limited to student perception, as teachers also seem to associate boys with more problems. In studies simply utilizing the label of “boy” without any further characteristics, teachers perceived male students as troublesome and disruptive (Glock & Kleen, 2017; Jones & Myhill, 2004). They also reported more feelings of rejection towards boys they described as more masculine (Piché & Plante, 1991), even when masculinity as defined in this previous investigation included both negative and positive traits.

Most of the research on the role of maleness and masculinity for academic outcomes at school has looked at “boys behaving ‘laddish’ or ‘macho’” (Lyng, 2009, p. 463), focusing on a particular subset of masculinities in school. This subset includes being loud (Heyder & Kessels, 2015), aggressive (Krahé et al., 2007), or not respecting rules and authorities (Jackson & Dempster, 2009). Studies have investigated this specific negative type of masculinity and its role in boys’ underachievement, finding that negative masculinity (Kessels & Steinmayr, 2013), “laddishness,” (Jackson, 2002; Jackson & Dempster, 2009), and traditional masculinity (Huyge et al., 2015; Yavorsky et al., 2015) relate to boys’ poorer academic behavior and achievement. Additional research shows that an orientation towards traditional masculine gender roles relates to worse academic performance (Hadjar & Lupatsch, 2010; Yavorsky & Buchmann, 2019; Yavorsky et al., 2015). Stronger beliefs in traditional gender roles have also been linked with lower levels of school belonging, particularly for boys (Huyge et al., 2015). Another study revealed that negative, but not positive, masculinity was associated with boys’ disadvantageous academic help-seeking behavior and worse grades. The absence of effects of negative femininity in this study was interpreted as strong evidence that the determining factor driving the detrimental outcomes was not the negativity of traits but rather the gender typicality (Kessels & Steinmayr, 2013). Research with teachers also points at a lower perceived fit between maleness or masculinity and school. Teachers ascribed the least academic engagement to adolescent boys who enacted socially undesirable masculinity but did not react to adolescent girls showing socially undesirable femininity to the same extent (Heyder & Kessels, 2015).

Given these findings, it may be tempting to view masculinity as a detriment in school. However, since most studies have explicitly focused on negative or “laddish” masculinity (Heyder & Kessels, 2015; Huyge et al., 2015; Jackson, 2002; Jackson & Dempster, 2009; Kessels & Steinmayr, 2013; Yavorsky et al., 2015), such a conclusion discounts the fact that there are more ways of defining and enacting masculinities. Some characteristics associated with masculinities have a positive relation to academic performance. For instance, one study revealed that assertiveness is seen as a trait required for success in school and was associated more with male than female students (Verniers et al., 2016).

In addition, studies citing masculinity as a negative asset at school stand in stark contrast with the many findings in adults on the benefits of masculine traits, defined as agency and instrumentality. In adult samples, higher instrumentality is related to lower anxiety and higher global self-esteem (Sharpe et al., 1995); and agency (Abele et al., 2016; Gebauer et al., 2013; Wojciszke et al., 2011) or masculinity (Whitley & Gridley, 1993) are positively related to global self-esteem. Professional success is also positively related to agency (Abele et al., 2008) and masculinity (Koenig et al., 2011). So far, research on instrumentality in the school context is scarce, although one study showed it was associated with higher self-esteem in Korean students (Choi et al., 2010).

The present study will first investigate whether a specific facet of masculinity, instrumentality, relates to positive outcomes in students. Secondly, we will study whether these relations differ for male and female students.

Does the Impact of Masculinity and Femininity Vary With Gender?

The results described above highlight the relevance of agency and instrumentality as important aspects of masculinities for well-being and professional success, though it would be simplistic to assume that this relation is equal for men and women or boys and girls. Studies that investigate both gender and gender role self-concept show that traits associated with masculinity and femininity can have differential relations in women and men. Indeed, the associations with masculinity and femininity seem to be even stronger when they do not align with gendered expectations and are thus experienced counter-stereotypically. The relation between masculinity and global self-esteem is often stronger in women than in men (Whitley, 1988), a finding also seen in the relation between agency and global self-esteem (Hirokawa & Dohi, 2007). While some researchers find higher well-being in men than women scoring high on femininity (Matud et al., 2019), others report no relation between femininity and self-esteem (Whitley, 1988) and communion and self-esteem in men (Hirokawa & Dohi, 2007; Wojciszke et al., 2011). Whether these trends of gender-differential effects extend to students remains to be investigated.

In adolescence, gender typicality is rewarded by higher peer status (Egan & Perry, 2001), and this was found to be especially true for boys (Jewell & Brown, 2014). Our research is based on the idea that precisely because instrumentality is perceived as typical for male, but less typical for female individuals (given the construction of the respective measurement tools), the self-reported instrumentality of female adolescents should be more predictive. While male adolescents scoring high on instrumentality may simply be applying gender stereotypes to themselves, girls’ endorsement of instrumentality might indicate that they agree with these items because it reflects traits they feel they possess. As “there is little data regarding the implications of masculinity for women” (Smiler, 2006, p. 622), the present research aims to illuminate how instrumentality in the school context impacts both male and female adolescents.

Relations of Gender Role Self-Concept to Students’ Motivation and Self-Esteem

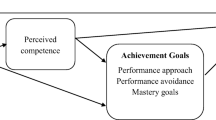

Important variables relevant to school students include achievement motivation as well as global and contingent self-esteem. Achievement motivation captures how students engage with challenges and process successes and failures (McClelland et al., 1953). Global self-esteem relates to an overall estimation of the self (Rosenberg, 1965), while contingent self-esteem captures the degree to which self-esteem is dependent on external factors (Crocker et al., 2003a, b). The relevance of these constructs is supported by their relation to well-being (Burwell & Shirk, 2006; Otterpohl et al., 2020) and their continued influence into adulthood (Abele et al., 2016; Crocker & Park, 2004; Gebauer et al., 2013; Otterpohl et al., 2020; Whitley & Gridley, 1993; Wojciszke et al., 2011; Zuckerman et al., 2016). The relations of these variables with gender role self-concepts have not been sufficiently investigated in adolescent samples, a gap this paper attempts to address. A visual representation of the proposed directions and relations between constructs can be found in Fig. 1.

Gender Role Self-Concepts and Achievement Motivation

The most prominent model in research focusing on gender differences in students’ motivation is the Eccles-Parsons et al. (1983) expectancy-value model of achievement-related choices, persistence, and performance (e.g., Eccles-Parsons et al., 1983; Eccles & Wigfield, 2020; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). This model has been applied to various domains, with many studies focusing on girls’ disadvantage in STEM resulting from their lower expectancy of success and task values related to STEM subjects. However, little attention has been given to the impact of students’ gender role self-concepts (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020). Recent research on other motivational constructs such as achievement goal orientations (Butler, 2019) or controlled versus autonomous motivational regulation (Vantieghem & Van Houtte, 2018) state that investigations of gender differences tend to be scarce (Butler, 2019) or “secondary” (Vantieghem & Van Houtte, 2018, p. 381) to the central research question, rather than the focus.

The motivational construct examined in the present study is achievement motivation, comprising fear of failure and hope for success (McClelland et al., 1953). Fear of failure can be characterized as experiencing discomfort at the thought of failing to display one’s abilities, while hope for success encompasses the desire to improve one’s abilities (Engeser, 2005; Steinmayr & Spinath, 2009a; Steinmayr et al., 2019). Hope for success was found to contribute positively to general school performance (Steinmayr & Spinath, 2009b), while fear of failure was associated with higher anxiety, self-handicapping, and low resilience (Martin & Marsh, 2003). A meta-analysis (Severiens & Dam, 1998) as well as a study from Germany (Engeser, 2005) highlighted that women scored higher on fear of failure than men. Comparable findings have been obtained among German high school students (Steinmayr & Spinath, 2008) and Norwegian elementary school students (Gjesme, 1983), while these studies showed no gender differences in hope for success.

Little is known about how gender role self-concepts relate to hope for success or fear of failure in middle adolescence. A review of studies conducted with college-aged samples highlights that individuals who rated themselves as holding high levels of stereotypically masculine traits had a more advantageous achievement motivation than those who reported higher levels of stereotypically feminine traits (Elmen, 1991; Major, 1979), a finding seen also for individuals with higher agency (Strage, 1997). One early study with college students (Orlofsky & Stake, 1981) revealed that self-attributed masculinity seemed to be a more powerful predictor of achievement motivation than gender. Participants scoring high in masculinity also scored higher in hope for success (Henschen et al., 1982) as well as scoring lower in fear of failure (Orlofsky & Stake, 1981).

Gender Role Self-Concepts and Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is an important resource in both adults and adolescents (Fairlamb, 2020). Global self-esteem in a school context has been shown to relate to higher grades (Crocker et al., 2003a, b), higher motivation, and lower school burnout (Herrmann et al., 2019). In contrast, having high academic contingent self-esteem places additional stress on students to achieve good results, as not only their academic reputation but their feeling of self-worth is perceived to be at risk (Burwell & Shirk, 2006; Crocker & Park, 2004; Fairlamb, 2020; Herrmann et al., 2019). Indeed, researchers have found relations between highly contingent self-esteem and depressive symptoms (Burwell & Shirk, 2006; Otterpohl et al., 2020) and lower global self-esteem (Moore & Smith, 2018; Schöne & Stiensmeier-Pelster, 2016; Schöne et al., 2015). The following sections will illuminate how self-esteem has been investigated in student samples in relation to gender and gender role self-concepts.

Global Self-Esteem

Mirroring research with adult samples, studies typically show that adolescent boys score higher on measures of global self-esteem than girls (Bleidorn et al., 2016; Block & Robins, 1993; Kling et al., 1999; Knox et al., 1998; Schöne & Stiensmeier-Pelster, 2016). Extending focus to gender role self-concept has revealed the positive relation between masculinity and global self-esteem in adolescents (Allgood-Merten & Stockard, 1991; Buckley & Carter, 2005; Cate & Sugawara, 1986), a relation also found for instrumentality (Choi et al., 2010) and agency (Stein et al., 1992).

Some early studies have revealed that the association between masculinity and global self-esteem is stronger for female than male adolescents (Allgood-Merten & Stockard, 1991; Cate & Sugawara, 1986), parallel to findings in adult samples with measures of masculinity (Matud et al., 2019; Whitley, 1988) and agency (Hirokawa & Dohi, 2007). Recently, Fu and Wang (2020) argued that there is a lack of more current research concerning the relation between gender role self-concept and self-esteem in adolescence.

Academic Contingent Self-Esteem

Adolescent girls score higher on academic contingent self-esteem than boys (Herrmann et al., 2019; Moore & Smith, 2018; Schöne & Stiensmeier-Pelster, 2016; Schöne et al., 2015; Van der Kaap-Deeder et al., 2016). However, the relation between gender role self-concept and contingent self-esteem is less established. An investigation on women in Poland did not find an association between masculinity, as measured by an adaptation of the BSRI (Bem, 1974), and academic contingent self-esteem (Mandal & Moroń, 2019), but research with adolescents in schools is needed.

One may assume that a negative association between academic contingent self-esteem and instrumentality would emerge in student samples, given the stereotype of school and learning being feminine (Heyder & Kessels, 2013, 2015). Students scoring high on instrumentality might be less likely to tie their self-esteem to their academic performance, while students scoring high in expressiveness may stake more of their self-esteem on achievements in this supposedly feminine sphere. The inverse relation between global and contingent self-esteem (Moore & Smith, 2018; Schöne & Stiensmeier-Pelster, 2016; Schöne et al., 2015) and the strong association of global self-esteem with masculinity (Allgood-Merten & Stockard, 1991; Buckley & Carter, 2005; Cate & Sugawara, 1986) and instrumentality (Choi et al., 2010) further leads us to believe that instrumentality would show a negative relation with academic contingent self-esteem.

Study Overview and Hypotheses

The present study investigated the importance of instrumental gender role self-concepts (instrumental self-concepts) for secondary school students’ achievement motivation and self-esteem while comparing whether these relations differ for male and female students (see Fig. 1). We also considered achievement motivation and self-esteem simultaneously, as these constructs have been shown to relate to one another. Given the existing findings in adult samples on the positive outcomes of masculinity, agency, and instrumentality (Abele, 2003; Abele & Candova, 2007; Abele et al., 2008; Hirschy & Morris, 2002; Matud et al., 2019; Whitley, 1984), we constructed a model in which global self-esteem, academic contingent self-esteem, fear of failure, and hope for success were regressed on instrumentality.

We expected that students scoring high on instrumentality will likely also display higher global self-esteem, as traits associated with masculinity are highly valued and have been associated with higher self-esteem (Allgood-Merten & Stockard, 1991; Buckley & Carter, 2005; Cate & Sugawara, 1986; Choi et al., 2010; Stein et al., 1992). We further hypothesized that high scores in instrumentality would be associated with low academic contingent self-esteem, due to findings that school and learning is perceived as a feminine domain (Heyder & Kessels, 2013; Jackson & Dempster, 2009). Furthermore, we expected that instrumentality would be positively associated with hope for success and negatively associated with fear of failure, as instrumentality captures traits like independence and fearlessness and the respective relations had been reported in young adults (Elmen, 1991; Henschen et al., 1982; Major, 1979; Orlofsky & Stake, 1981; Strage, 1997).

Our model will also investigate relations between the two self-esteem constructs and fear of failure. We expect that high global self-esteem should be associated with lower fear of failure since individuals who have a positive view of the self are expected to be secure in their abilities. This relation has been found in the past, with researchers describing the strong negative relation between global self-esteem and fear of failure (e.g., Jöstl et al., 2012; Radziwiłłowicz & Macias, 2014). Academic contingent self-esteem is expected to relate positively to fear of failure, as students who place their sense of self-worth in academic domains are more likely to report distress at the idea of failing in this domain. Furthermore, researchers have stated that fear of failure would be particularly pronounced in individuals with highly contingent self-esteem (Crocker & Park, 2004). Research offers robust evidence that fear of failure is related to the different aspects of self-esteem (Aktop & Erman, 2006; Jöstl et al., 2012; Radziwiłłowicz & Macias, 2014) but less strong evidence for how hope for success relates to self-esteem (Aktop & Erman, 2006). Consequently, an indirect relation via global self-esteem and academic contingent self-esteem is hypothesized only for fear of failure.

Overall, we investigate how students’ instrumental self-concept is related to fear of failure via global self-esteem and academic contingent self-esteem and how their instrumental self-concept relates to hope for success. Additionally, based on research showing larger relations of counter-stereotypical self-descriptions on a variety of outcomes in adult samples (Hirokawa & Dohi, 2007; Whitley, 1988; Wolfram et al., 2009), we expected the relations of instrumentality with the other constructs to be moderated by participants’ gender, with stronger relations to be found among female students than male students. We also conduct two exploratory analyses using grades and expressiveness as additional variables. We regressed fear of failure and hope for success on grade average and also constructed a separate model in which both self-esteem constructs and achievement motivation were regressed on expressiveness.

Method

Participants and Procedure

In total, 648 9th grade students participated in one larger study. The scales for the motivational constructs (hope for success and fear of failure) had been administered to a subsample of 288 students. The students completed a paper and pencil questionnaire while supervised by two trained student assistants. The data collection took place in the classroom in the middle of the year and was conducted instead of a regular lesson. All participants attended the “Gymnasium,” the highest academic track in Germany. As girls are overrepresented in this track (53% female students; Federal Statistical Office Germany, 2020), this imbalance was mirrored in our sample too, resulting in a relatively low number of male adolescents for our main analyses. In order to attain a balanced sample, 60 male adolescents were additionally chosen at random from the group of students that had not been given the measures of the motivational constructs and added to the sample. Three students did not indicate their gender and were excluded from the analyses. Thus, the final sample consisted of 355 students from six schools.

On average, the students were 14.2 years old (SD = 0.5, range = 13−17) and half of the sample identified as female (50.6%). In addition to these constructs, participants also provided information on personality (such as the big-five personality traits) and school-related questionnaires (such as perceived support through teachers, academic self-regulation), none of which were used in the present research. Neither socioeconomic status nor parental education were collected as part of this study.

Measures

Instrumentality and expressiveness were assessed using a German measure (Kessels, 2005) comprising 30 attributes (15 expressive: e.g., “helpful,” “considerate,” “gentle”; 15 instrumental: e.g., “proud,” “powerful,” “fearless”; for all items, see Table S1 in the online supplement). This scale had been constructed by asking German adolescents how typical different traits were for a girl and for a boy. Students in the present study were asked to indicate the degree to which the traits apply to themselves on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (does not apply at all) to 7 (strongly applies). Based on inadequate loadings (λ < .45) in confirmatory factor analyses, six items were removed from the instrumentality scale and six items from the expressiveness scale (all factor analyses were conducted in the second half of the sample which did not fill in the motivational construct scales). Both final scales showed good reliability (Cronbach’s αinstrumentality = .86 and Cronbach’s αexpressiveness = .85).

Global self-esteem was assessed with the Self-Esteem Inventory for Children and Adolescents (SEKJ; Schöne & Stiensmeier-Pelster, 2016), a German scale used to assess self-esteem on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Examples from the 10-item scale include “I like myself,”and “I am completely satisfied with myself.” Based on a confirmatory factor analysis, two items that had low loadings and referred to liking specific aspects of oneself (looks and name) were excluded. The final scale had good reliability, Cronbach’s α = .88.

Academic contingent self-esteem was measured with the respective subscale from the above-mentioned Self-Esteem Inventory for Children and Adolescents (Schöne & Stiensmeier-Pelster, 2016). This 11-item scale, also presented in German, was scored on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), e.g., “When I get better grades than my classmates, I feel more worthy.” A confirmatory factor analysis indicated that all items should be retained. Reliability of the scale was very good, Cronbach’s α = .91.

Achievement motivation was measured using the German achievement motivation scale (Engeser, 2005), which separates achievement motivation into hope for success and fear of failure, each subscale consisting of 5 items (10 items total). Hope for success was measured with statements such as “I would like to be given more difficult tasks,” while fear of failure was characterized by items such as “If I do not understand a problem immediately I start feeling anxious.” Items were rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (does not apply at all) to 4 (strongly applies). Based on inadequate loadings in a confirmatory factor analysis, three items were removed from the hope for success scale. No changes were indicated for the fear of failure scale. Reliability was adequate for the hope for success scale (Spearman-Brown coefficient = .77) and good for fear of failure (Cronbach’s α = .83).

In an exploratory analysis outlined in more detail in the following section, we also included students’ achievement. This academic achievement score consisted of self-reported grades in the three main subjects (German, Math, English), which were then averaged. In the German school system, higher grade averages indicate worse performance.

Analysis Plan

We tested our hypotheses using structural equation modelling, which allows us to test our set of hypotheses in one rather than multiple models. Moreover, we used latent variables for all constructs, making our path estimates more reliable. All analyses were conducted using the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) in R (R Core Team, 2017). We conducted a multi-group SEM to compare the relations between instrumentality, achievement motivation, and self-esteem constructs separately for male and female students. To reduce the number of paths tested, parcels were used instead of items for constructs with more than five items. The rationale for using parcels and the analysis plan were preregistered and can be accessed via the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/m8n49/). Please note that we provided a respecified model guided by theory as recommended by Kline (2016), which is the model presented here.

Exploratory Analyses

In addition to this analysis, we conducted exploratory analyses that included two control variables. In one set of analyses, we included grade average as a predictor of fear of failure and hope for success and tested these additional paths for equivalence between the genders. In another set of analyses, we added expressiveness to the model as a predictor for self-esteem, self-esteem contingency, and motivational constructs. These additional paths were tested for equivalence as well.

Missingness

Most commonly, participants did not have any missing values (72.1%), and another 16.9% had missingness by design on the fear of failure and hope for success scales (the 60 male adolescents randomly chosen from the other subsample). The remaining 9.6% had either failed to fill in individual items or did not answer the 11-item scale on contingency of self-esteem. In total, 3.9% of cells were missing. Since we knew that the majority of missingness was missing by design (MCAR), we used FIML (Full-Information Maximum Likelihood) to estimate missing values for all SEM analyses.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics as well as correlations between the means of instrumentality and the self-esteem and motivational constructs are presented in Table 1, separated by gender. Correlations indicated that all constructs were (in part marginally) associated with one another for female adolescents, whereas this was not the case for male adolescents. On all scales, male and female students significantly differed in their mean values such that male students described themselves as more instrumental, less expressive, more hopeful, and less fearful. Moreover, they had higher global self-esteem, and this self-esteem was less contingent on academic competence.

Main Model: Instrumentality

We regressed global self-esteem, academically contingent self-esteem, fear of failure, and hope for success on instrumentality. In addition, fear of failure was regressed on global self-esteem and academically contingent self-esteem (Fig. 2). The χ2-test for the fully-latent two-group model was significant, χ2(205) = 297.89, p < .001, which could be indicative of poor model fit; however, model fit indices presented a different picture with adequate to good fit, CFI = .96, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .09. Thus, the results should be interpreted with caution. To test whether gender moderated any of the paths, we followed a model trimming approach as described by Kline (2016). From the starting model in which all paths were free to vary across the two groups, nested models were tested in which each regression path was individually constrained to be equal for both genders. In one instance this reduced model fit at p < .05, indicating that the coefficients of this path were different for male and female adolescents. For adolescent girls the relation between instrumentality and global self-esteem was stronger, since constraining the coefficient to be equal for both genders worsened model fit, χ2Δ(1) = 4.89, p = .03. All other regression paths were constrained to be equal. Thus, in the final model we constrained all paths apart from global self-esteem on instrumentality to be equal for male and female adolescents. This model had good model fit when considering the model fit indices, CFI = .96, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .09, but the χ2-test remained significant, χ2(210) = 304.12, p < .001. In the text, we report the values of the coefficients constrained to be equal (i.e., collapsed across both genders), with the exception of the coefficient that differed significantly between boys and girls (see Fig. 2 for the unconstrained model, which includes separate values of all coefficients).

Main Model Regressing Instrumentality on the Self-Esteem and Motivational Constructs. Note. Results of the fully-latent two-group model without equality constraints for the path coefficients. Standardized coefficients are first presented for female and then for male adolescents. The coefficients are significantly different for boys and girls only for the path between masculinity and global self-esteem (in bold). χ2(205) = 297.89, p < .001, CFI = .96, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .09. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

The regression coefficients indicated that ascribing more instrumental traits to oneself was associated with greater self-esteem (female adolescents: b = 0.44, SE = 0.07, p < .001; male adolescents: b = 0.25, SE = 0.09, p = .005), and these findings are thus consistent with our hypotheses. For example, an adolescent girl who rated herself one point higher on the scale of instrumentality than the mean for girls also rated her self-esteem about half a point above the mean on the self-esteem scale in this group. An adolescent boy rating himself one point above the mean for instrumentality also had a higher self-esteem score than a boy with an average score on instrumentality —but only about one fourth of a point higher. Consistent with the hypotheses laid out above, both female and male students who scored higher on instrumentality also scored lower on academic contingent self-esteem (b = −0.20, SE = 0.05, p < .001). As such, a student with instrumentality one point above the mean also had about a fifth of a point lower score on contingency of self-esteem compared to students with average instrumentality. Additionally, greater instrumentality was associated with less fear of failure for both male and female adolescents (b = −0.14, SE = 0.04, p = .001) and was related to greater hope for success (b = 0.15, SE = 0.06, p = .012), which is in line with the hypothesized associations. In turn, higher global self-esteem and lower contingency of self-esteem were associated with less fear of failure (b = −0.12, SE = 0.05, p = .010, and b = 0.32, SE = 0.06, p < .001, respectively), findings which are consistent with our hypotheses.

Next, we examined the indirect effects of instrumentality on fear of failure through global self-esteem. For female adolescents, instrumentality was negatively associated with fear of failure via global-self-esteem, b = −0.05, SE = 0.02, p = .014, bootstrapped 95% CI [−0.10, −0.02]. However, the indirect effect for male adolescents did not reach the traditional significance threshold, b = −0.03, SE = 0.02, p = .055, bootstrapped 95% CI [−0.07, −0.01]. Lastly, the indirect effect via contingency of self-esteem also differed from zero, b = −0.06, SE = 0.02, p = .002, bootstrapped 95% CI [−0.12, −0.03]. Overall, this model explained fear of failure well (R2females = .470; R2males = .362) as well as self-esteem when it came to female students (R2females = .302; R2males = .085). However, self-esteem contingency and hope for success remained largely unexplained for both genders (R2females = .094; R2males = .057, and R2females = .085; R2males = .043, respectively).

Exploratory Analyses

In addition to our main analysis, we included two additional variables that could relate to the constructs examined in our main model. First, we included expressiveness to test whether this aspect of gender role self-concept might similarly relate to both self-esteem and motivational constructs. In a second model, we added grade average to the model and regressed fear of failure and hope for success on it.

The results of the exploratory analyses are presented in Table 2. When including expressiveness in the model, it was positively associated with fear of failure such that greater expressiveness was associated with greater fear of failure, though the coefficient was small in size. Expressiveness was not associated with other constructs at p < .05. Including expressiveness in the model did not change the relations between the other constructs, though the size of the coefficients of the paths predicting fear of failure from instrumentality and self-esteem contingency was somewhat smaller.

When grades were included as predictors of fear of failure and hope for success they were associated with fear of failure but more so with hope for success. Specifically, worse grades were related to lower hopes for success and greater fear of failure. Including grades in the model did not affect the size of other path coefficients.

Discussion

We investigated whether having a strong instrumental self-concept would be associated with achievement motivation and two aspects of self-esteem and whether these relations were equally strong for both adolescent girls and boys. We found that a stronger instrumental self-concept was associated with greater global self-esteem and lower academic contingent self-esteem, which, in turn, were each associated with lower fear of failure. One of the examined relations was different in female students than in male students. In particular, the relation between instrumentality and global self-esteem was stronger for adolescent girls. Moreover, instrumentality indirectly related to fear of failure through global self-esteem in female but not male adolescents.

Our descriptive results showed that adolescent boys scored higher on global self-esteem than adolescent girls. The structural equation model indicated that instrumentality was positively associated with global self-esteem in both genders, with this relation being stronger in female students. Our present results support past findings in which male gender (Bleidorn et al., 2016; Block & Robins, 1993; Kling et al., 1999; Knox et al., 1998; Schöne & Stiensmeier-Pelster, 2016) and higher masculinity (Allgood-Merten & Stockard, 1991; Buckley & Carter, 2005; Cate & Sugawara, 1986), agency (Stein et al., 1992), and instrumentality (Choi et al., 2010) have been found to relate to higher global self-esteem in adolescents.

Past research on academic contingent self-esteem has established that female students tend to score higher in this domain, indicating that they attach their self-esteem to their academic performance to a greater extent than male students (Moore & Smith, 2018; Schöne & Stiensmeier-Pelster, 2016; Schöne et al., 2015; Van der Kaap-Deeder et al., 2016). Our present research corroborates these findings, with adolescent girls scoring higher on this measure than boys. Research on the relation between gender role self-concept and academic contingent self-esteem is scarce, though one study using an adult sample found no association between these constructs (Mandal & Moroń, 2019). We hypothesized that students who see themselves as having more instrumental characteristics may also place less importance on academic pursuits. This hypothesis was supported in our analysis. Instrumentality seems to serve as a buffer against grounding one’s self-worth in success at school. This could be due to the stereotyping of school and learning as feminine (Heyder & Kessels, 2013; Jackson & Dempster, 2009), which may discourage students displaying traits traditionally associated with masculinity from attaching self-esteem to this domain. If successful academic performance is not as central to one’s self-esteem, failure is not as threatening to a positive self-image and fear of failure should therefore be lower, as has been demonstrated in our data. Additionally, the high degree of independence, which is part and parcel of the construct of instrumentality itself, implies that also the self-esteem of persons scoring high on instrumentality should be less contingent on external sources such as academic success.

In line with previous findings (Engeser, 2005; Steinmayr & Spinath, 2008), male adolescents scored higher than female adolescents on hope for success, while female students displayed higher scores on fear of failure. Findings also illustrated that instrumentality was associated with lower fear of failure and higher hope for success, which suggests that adolescent girls and boys may benefit from a more instrumental self-concept. These results are in line with past research with adults (Orlofsky & Stake, 1981), in which a masculine gender role self-concept was related to an advantageous achievement motivation (Elmen, 1991; Henschen et al., 1982; Major, 1979; Strage, 1997). Our study fills an important gap in the literature, as we are able to provide insight into the relation between gender role self-concepts and achievement motivation in adolescents, an area in which modern studies are lacking.

Our findings also relate to research on motivational constructs which are more domain-specific and are often studied within the expectancy-value model (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020). Academic self-concepts in different domains, commonly used as a proxy for expectation of success, have been studied in relation to students’ gender-role self-concept. Some studies found that the endorsement of traits typically associated with femininity relate to higher verbal self-concepts (McGeown & Warhurst, 2020; Pajares & Valiante, 2001), while scores on masculinity display a weaker positive relation with math self-concepts (McGeown & Warhurst, 2020; Wolter & Hannover, 2016). Our study extends these findings by focusing domain-independent motivational constructs. As instrumentality was related to higher hope for success and lower fear of failure, it could follow that instrumentality may relate to greater expectations of success in general (Vollmer, 1986).

Differential Relations by Gender

As predicted, we found a stronger relation between female adolescents’ instrumentality and their global self-esteem compared to male adolescents. Moreover, the indirect relation between instrumentality and fear of failure through self-esteem was only significant for female adolescents. Based on the idea of the prescriptive function of gender stereotypes (Eagly, 1983, 1987; Eagly & Karau, 2002), we hypothesized that a student’s ascription of counter-stereotypical traits will, in fact, be more predictive for other psychological outcomes than the ascription of traits that are perceived as typical of one’s own gender. It follows that when women or girls endorse traits traditionally associated with masculinity, these should be traits they truly feel reflect their self-image and thus be able to predict their other characteristics, too. In contrast, men or boys endorsing traits associated with masculinity might, in some cases, simply be describing themselves in line with the male gender stereotype, without actually perceiving themselves the way they indicated on measurements. Our findings are in line with research utilizing complex gender role profiles (Lyng, 2009) showing that the most adaptive behavior patterns were exhibited by adolescents who resisted traditional gender norm ideals (Yu et al., 2020) and that gender typicality relates to academic achievement differently for adolescent girls and boys (Yavorsky & Buchmann, 2019).

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Like many psychological investigations, our data are cross-sectional and thus do not allow us to test causal links between the variables laid out above (Kline, 2016; Maxwell & Cole, 2007). Path models are formulated based on assumptions about the directionality of relations, and these assumptions themselves are not directly tested but rely on characteristics of the dataset (e.g., cross-sectional vs. longitudinal data). While some paths are likely only in one direction (e.g., relating to demographic variables such as gender), this is not the case for the constructs in our study. For example, there might exist a self-reinforcing mechanism over time such that self-esteem leads to lower fear of failure, while having lower fear of failure might lead one to ascribe more instrumental traits to oneself when asked (e.g., proud, powerful, fearless). The directionality of the relations can therefore not be conclusively determined based on the results in our dataset (Kline, 2016; Maxwell & Cole, 2007). Future research should examine the question of gender-differential effects of instrumentality on self-esteem and motivational constructs in longitudinal data.

Secondly, the sample was drawn from a large city in Germany, which, while diverse, may not be reflective of all cities within the nation. Perhaps, more importantly, the sample recruited for this study stems from the “Gymnasium,” an academic track which only represents one of several types of academic environment. While over 40% of students attend this track (Federal Statistical Office Germany, 2020), these students are typically in higher socioeconomic classes than students from outside this track (Reiss et al., 2016). Generalizing to these other academic tracks may be difficult, as these students may display different patterns of achievement motivation, global self-esteem, and academic contingent self-esteem. Interestingly, gender role self-concept is theorized to vary according to socioeconomic status (SES), with qualitative studies showing higher SES parents encouraging more instrumental traits in their daughters (Friedman, 2013) and lower SES intertwined with more traditional masculinity in male adolescents (Morris, 2008). A recent quantitative study, however, found no relation between SES and gender typicality (Yavorsky & Buchmann, 2019). These results highlight the complicated relation between socioeconomic status and gender role self-concept, which we cannot speak to on an empirical level, given that we were not able to investigate socioeconomic status in this study.

Moreover, it should be kept in mind that the χ2-test was significant for the SEM, indicating that the observed variance–covariance matrix was not reproduced by the model. Though the reliance on (only) χ2-tests is somewhat debated (e.g., Barrett, 2007; Markland, 2007) and both absolute and relative fit indices imply good fit, coefficients should be interpreted with care. A replication of this model in a different data set could provide further support for differential relations of gender role self-concept for male and female adolescents. In addition, replications could address potential sources for a lack of fit in the present model. For example, our model may have omitted a relevant variable such as social class that could predict endogenous variables in our model or moderate the relations between those variables already included in the model. Thus, future research should examine whether additional, theoretically relevant variables could influence self-esteem and/or motivational constructs in school children.

We also wish to stress the importance of developing measures and designs that allow researchers to better detect whether response patterns regarding gender-typed attributes might reveal participants’ actual traits and/or whether they reflect participants’ knowledge of and willingness to conform to gender stereotypes (Tobin et al., 2010). The present findings indicate that especially counter-stereotypical descriptions might reveal the traits adolescents feel they possess, as responding counter-stereotypically represents a rejection of gender stereotypes. Contrastingly, responses in line with stereotypical descriptions might be a reaction to pressure from gender stereotypes and thus may not show the traits with which adolescents truly identify.

Further research in this area is needed in order to better understand what it actually means when individuals ascribe gender-typed attributes to themselves. Tobin et al. (2010) have pointed to the multiple dimensions of gender identity. Their gender self-socialization model (GSSM) explicates how attribute self-perception (this is what the instruments used in our study captured) has to be conceptualized as distinct from self-perceived gender typing (gender identity). The authors note that people might ascribe instrumental or expressive traits to themselves without considering these traits as masculine or feminine. It may be the case that self-ascriptions of characteristics considered gendered by others may not be categorized as masculine or feminine by the individual making the ascription (Tobin et al., 2010). The complex and personal beliefs surrounding gender and its associated traits may differ from adolescent to adolescent, and capturing these ideas in a few items may fail to depict certain aspects of an individual’s concept of gender. While the overarching categories of masculinity and femininity are relevant terms for this paper, given as they resonate with gender stereotypes in public consciousness (Rudman & Glick, 2008), it is not guaranteed that the traits resonating with adolescents are gendered in their minds.

However, since people on average seem to possess more, deeper, and more fine-grained knowledge about own-gender traits and behavior, the knowledge about own-gender stereotypes might also be larger than the knowledge about other-sex stereotypes (Martin et al., 2002). Thus, regardless of whether a person considers these traits explicitly masculine or feminine, own-gender traits should be more familiar and, since being more familiar leads to more liking and approval (Bornstein, 1989; Zajonc, 1968), being more of an expert in own-gender traits will make the endorsement of these more likely as compared to the endorsement of other-gender traits. Our study adds to our understanding that the endorsement of gendered traits might have different significance for male and female individuals; as for self-esteem, the endorsement of gender-role incongruent traits was more predictive than the endorsement of gender-role congruent traits.

As gender stereotypes are not static and shift across time, women are being ascribed more competence in recent decades, and social attitudes shift towards egalitarianism, we may see stereotype contents changing to reflect these changes, too (Eagly et al., 2020). Of course, as masculinity (as well as femininity) is a complex, fluid construct (Eagly et al., 2020) that can comprise a variety of traits (Berger & Krahé, 2013), not all types or aspects of masculinity may be helpful in academic contexts. One popular strain of research has investigated gender differences in school through the lens of a specific type of masculinity, for example, “laddish,” or “negative,” or “traditional” masculinities, finding such masculinities to be problematic in academia (Glock & Kleen, 2017; Heyder & Kessels, 2013, 2015; Huyge et al., 2015; Jackson, 2002; Jackson & Dempster, 2009; Jones & Myhill, 2004; Kessels & Steinmayr, 2013; Yavorsky et al., 2015). In contrast, the present study examined instrumentality as one dimension of masculinity and found it to be associated with positive outcomes.

However, some positive aspects associated with instrumentality, such as higher global self-esteem recorded in multiple studies including the present paper, could also have negative effects in an academic context. Seeking help was observed to be less likely in individuals scoring high on self-esteem (Tessler & Schwartz, 1972), highlighting the delicate balance between beneficial and detrimental outcomes of certain traits. Gendered traits have a complex relation with academic performance and while this paper suggests that some aspects of masculinity, such as pride and fearlessness, may be helpful in the school context, this finding should not be extrapolated to other types of masculinities.

Practice Implications

The benefits of resisting strict gender roles has been exalted since the 70s (Bem, 1974) yet has not taken hold in the discourse on feminization of school until recently (Yu et al., 2020). A more careful consideration of the multifaceted impact of masculinities in school would benefit male and female students, teachers, and parents. Adopting a new perspective that emphasizes the benefits of both expressive and instrumental self-concepts in school contexts (cf. Verniers et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2020) could present an advantage to adolescents. Challenging the view that schools are a feminine space may not only disrupt the alienation felt by boys in school (Hadjar & Lupatsch, 2010) but also the seemingly false promise school appears to make to female students: At school, behaviors that are rather typically feminine are reinforced through good grades, while in working life, success is related to quite different traits (Steinmayr & Kessels, 2017). Still, simply suggesting that female students should be encouraged to develop their instrumentality would be simplistic, as the possible impact of instrumentality has to be put into context. Studies taking the intersection of gender and socioeconomic status (Friedman, 2013) or ethnicity (George, 2015) into account have shown that traits associated with masculinity have the potential to interact with other identities.

Given the growing disillusionment with binary models of gender, it would be most preferable if the perception that certain traits reflect something masculine or feminine that applies exclusively to men or women, respectively, were abandoned (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). This would enable people of all genders to describe themselves with any trait they deem appropriate.

Conclusion

The present study investigated the association between instrumentality and achievement motivation in schools both directly and indirectly via multiple self-esteem constructs. While a certain type of masculinity has been portrayed as problematic in the school context, our findings point to positive associations between a different type of masculinity—instrumentality—and adaptive patterns of motivation and self-esteem in adolescents. The fact that one of these associations and an indirect effect were stronger in female than in male adolescents underlines that counter-stereotypical self-perceptions might be more powerful predictors than self-perceptions in line with gender stereotypes.

Availability of Data and Materials

Upon request.

Code Availability

Upon request.

References

Abele, A. E. (2003). The dynamics of masculine-agentic and feminine-communal traits: Findings from a prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(4), 768–776. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.768

Abele, A. E., & Candova, A. (2007). Prädiktoren des Belastungserlebens im Lehrerberuf: Befunde einer 4-jährigen Längsschnittstudie [Predicting teachers’ stress experience: Findings from a 4-year longitudinal study]. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogische Psychologie, 21(2), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652.21.2.107

Abele, A. E., Hauke, N., Peters, K., Louvet, E., Szymkow, A., & Duan, Y. (2016). Facets of the fundamental content dimensions: Agency with competence and assertiveness-communion with warmth and morality. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1810. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01810

Abele, A. E., Rupprecht, T., & Wojciszke, B. (2008). The influence of success and failure experiences on agency. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(3), 436–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.454

Abele, A. E., & Wojciszke, B. (2014). Communal and agentic content in social cognition: A dual perspective model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 50, 195–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800284-1.00004-7

Aktop, A., & Erman, K. A. (2006). Relationship between achievement motivation, trait anxiety and self-esteem. Biology of Sport, 23(2), 127–141.

Allgood-Merten, B., & Stockard, J. (1991). Sex role identity and self-esteem: A comparison of children and adolescents. Sex Roles, 25(3–4), 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00289850

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). American Psychological Association.

American Psychological Association Boys and Men Guidelines Group. (2018). APA guidelines for psychological practice with boys and men. http://www.apa.org/about/policy/psychological-practice-boys-men-guidelines.pdf

Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of human existence: An essay on psychology and religion. Rand McNally.

Barrett, P. (2007). Structural equation modelling: Adjudging model fit. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 815–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.018

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(2), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0036215

Bem, S. L. (1981). Bem sex-role inventory: A professional manual. Consulting Psychologist Press.

Berger, A., & Krahé, B. (2013). Negative attributes are gendered too: Conceptualizing and measuring positive and negative facets of sex-role identity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43(6), 516–531. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1970

Bleidorn, W., Arslan, R. C., Denissen, J. J. A., Rentfrow, P. J., Gebauer, J. E., Potter, J., & Gosling, S. D. (2016). Age and gender differences in self-esteem: A cross-cultural window. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(3), 396–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000078.supp

Block, J., & Robins, R. W. (1993). A longitudinal study of consistency and change in self-esteem from early adolescence to early adulthood. Child Development, 64(3), 909–923. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131226

Bornstein, R. F. (1989). Exposure and affect: Overview and meta-analysis of research, 1968–1987. Psychological Bulletin, 106(2), 265–289. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.265

Buckley, T. R., & Carter, R. T. (2005). Black adolescent girls: Do gender role and racial identity impact their self-esteem? Sex Roles, 53(9–10), 647–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-7731-6

Burwell, R. A., & Shirk, S. R. (2006). Self processes in adolescent depression: The role of self-worth contingencies. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16(3), 479–490. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00503.x

Butler, R. (2019). Gender, motivation, and society: New and continuing challenges. In E. N. Gonida & M. S. Lemos (Eds.), Motivation in education at a time of global change: Theory, research, and implications for practice (Vol. 20, pp. 129–149). Bingley, UK: CPI Group. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0749-742320190000020007

Cate, R., & Sugawara, A. I. (1986). Sex role orientation and dimensions of self-esteem among middle adolescents. Sex Roles, 15(3–4), 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00287480

Choi, H., Kim, J. H., Hwang, M. H., & Heppner, M. J. (2010). Self-esteem as a mediator between instrumentality, gender role conflict and depression in male Korean high school students. Sex Roles, 63(5–6), 361–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9801-7

Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender and Society, 19(6), 829–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205278639

Crocker, J., Karpinski, A., Quinn, D. M., & Chase, S. K. (2003a). When grades determine self-worth: Consequences of contingent self-worth for male and female engineering and psychology majors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(3), 507–516. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.507

Crocker, J., Luhtanen, R. K., Cooper, M. L., & Bouvrette, A. (2003b). Contingencies of self-worth in college students: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(3), 894–908. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.894

Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2004). The costly pursuit of self-esteem. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 392–414. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.392

Eagly, A. H. (1983). Gender and social influence: A social psychological analysis. American Psychologist, 38(9), 971–981. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.38.9.971

Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Erlbaum.

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-295X.109.3.573

Eagly, A. H., Nater, C., Miller, D. I., Kaufmann, M., & Sczesny, S. (2020). Gender stereotypes have changed: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of U. S. public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. American Psychologist, 75(3), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000494

Eccles-Parsons, J. S., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., & Midgley, C. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motivation (pp. 75–146). W. H. Freeman.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61(4), 101859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859

Egan, S. K., & Perry, D. G. (2001). Gender identity: A multidimensional analysis with implications for psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 37(4), 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.37.4.451

Elmen, J. (1991). Achievement orientation in early adolescence: Developmental patterns and social correlates. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 11(1), 125–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431691111006

Engeser, S. (2005). Messung des expliziten Leistungsmotivs: Kurzform der Achievement Motives Scale [Measuring the explicit achievement motive: A short version of the Achievement Motives Scale]. Universität Trier.

Fairlamb, S. (2020). We need to talk about self-esteem: The effect of contingent self-worth on student achievement and well-being. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000205

Federal Statistical Office Germany. (2020). Bildung und Kultur. Allgemeinbildende Schulen [Education and culture. General education]. Retrieved from: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bildung-Forschung-Kultur/Schulen/Publikationen/Downloads-Schulen/allgemeinbildende-schulen-2110100197004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

Friedman, H. L. (2013). Tiger girls on the soccer field. Contexts, 12(4), 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504213511213

Fu, C., & Wang, M. (2020). Parental corporal punishment and girls’ self-esteem: The moderating effects of girls’ agency and communion in China. Sex Roles, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01174-6

Gebauer, J. E., Wagner, J., Sedikides, C., & Neberich, W. (2013). Agency-communion and self-esteem relations are moderated by culture, religiosity, age, and sex: Evidence for the Self-Centrality Breeds Self-Enhancement principle. Journal of Personality, 81(3), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00807.x

George, J. A. (2015). Stereotype and school pushout: Race, gender, and discipline disparities. Arkansas Law Review, 68(101), 101–129.

Gjesme, T. (1983). Motivation to approach success (TS) and motivation to avoid failure (TF) at school. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 27(3), 145–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031383830270302

Glock, S., & Kleen, H. (2017). Gender and student misbehavior: Evidence from implicit and explicit measures. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.05.015

Hadjar, A., & Lupatsch, J. (2010). Der Schul(miss)erfolg der Jungen: Die Bedeutung von sozialen Ressourcen, Schulentfremdung und Geschlechterrollen [The lower educational success of boys: The impact of social resources, school alienation and gender role patterns]. Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie, 62(4), 599–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-010-0116-z

Henschen, K. P., Edwards, S. W., & Mathinos, L. (1982). Achievement motivation and sex-role orientation of high school female track and field athletes versus nonathletes. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 55(1), 183–187. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1982.55.1.183

Herrmann, J., Koeppen, K., & Kessels, U. (2019). Do girls take school too seriously? Investigating gender differences in school burnout from a self-worth perspective. Learning and Individual Differences, 69, 150–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.11.011

Heyder, A., & Kessels, U. (2013). Is school feminine? Implicit gender stereotyping of school as a predictor of academic achievement. Sex Roles, 69(11–12), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0309-9

Heyder, A., & Kessels, U. (2015). Do teachers equate male and masculine with lower academic engagement? How students’ gender enactment triggers gender stereotypes at school. Social Psychology of Education, 18(3), 467–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-015-9303-0

Heyder, A., & Kessels, U. (2017). Boys don’t work? On the psychological benefits of showing low effort in high school. Sex Roles, 77(1–2), 72–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0683-1

Heyder, A., Van Hek, M., & Van Houtte, M. (2021). When gender stereotypes get male adolescents into trouble: A longitudinal study on gender conformity pressure as a predictor of school misconduct. Sex Roles, 84, 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01147-9

Hirokawa, K., & Dohi, I. (2007). Agency and communion related to mental health in Japanese young adults. Sex Roles, 56(7–8), 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9190-8

Hirschy, A. J., & Morris, J. R. (2002). Individual differences in attributional style: The relational influence of self-efficacy, self-esteem, and sex role identity. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(2), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00003-4

Huyge, E., Van Maele, D., & Van Houtte, M. (2015). Does students’ machismo fit in school? Clarifying the implications of traditional gender role ideology for school belonging. Gender and Education, 27(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2014.972921

Jackson, C. (2002). Laddishness as a self-worth protection strategy. Gender and Education, 14(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250120098870

Jackson, C., & Dempster, S. (2009). I sat back on my computer … with a bottle of whisky next to me: Constructing cool masculinity through effortless achievement in secondary and higher education. Journal of Gender Studies, 18(4), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589230903260019

Jewell, J. A., & Brown, C. S. (2014). Relations among gender typicality, peer relations, and mental health during early adolescence. Social Development, 23(1), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12042

Jones, S., & Myhill, D. (2004). Troublesome boys and compliant girls: Gender identity and perceptions of achievement and underachievement. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 25(5), 547–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142569042000252044

Jöstl, G., Bergsmann, E., Lüftenegger, M., Schober, B., & Spiel, C. (2012). When will they blow my cover? The impostor phenomenon among Austrian doctoral students. Journal of Psychology, 220(2), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000102

Kessels, U. (2005). Fitting into the stereotype: How gender-stereotyped perceptions of prototypic peers relate to liking for school subjects. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 20(3), 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173559

Kessels, U., & Heyder, A. (2020). Not stupid, but lazy: Psychological benefits of disruptive classroom behavior from an attributional perspective. Social Psychology of Education, 23, 583–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-020-09550-6

Kessels, U., Heyder, A., Latsch, M., & Hannover, B. (2014). How gender differences in academic engagement relate to students’ gender identity. Educational Research, 56(2), 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2014.898916

Kessels, U., & Steinmayr, R. (2013). Macho-man in school: Toward the role of gender role self-concepts and help seeking in school performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 23(1), 234–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.09.013

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

Kling, K. C., Hyde, J. S., Showers, C. J., & Buswell, B. N. (1999). Gender differences in self-esteem: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125(4), 470–500. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.4.470

Knox, M., Funk, J., Elliott, R., & Bush, E. G. (1998). Adolescents’ possible selves and their relationship to global self-esteem. Sex Roles, 39(1–2), 61–77.

Koenig, A. M., Eagly, A. H., Mitchell, A. A., & Ristikari, T. (2011). Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 616–642. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023557

Korlat, S., Forst, N., Schultes, M., Schober, M. T., Spiel, B., & Kollmayer, M. (2021). Gender role identity and gender intensification: Agency and communion in adolescents’ spontaneous self-descriptions. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2020.1865143

Krahé, B., Berger, A., & Möller, I. (2007). Entwicklung und Validierung eines Inventars zur Erfassung der Geschlechtsrollenorientierung im Jugendalter [Development and validation of an inventory for measuring gender role self-concept in adolescence]. Zeitschrift Für Sozialpsychologie, 38(3), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1024/0044-3514.38.3.195

Lyng, S. T. (2009). Is there more to "antischoolishness" than masculinity? On multiple student styles, gender, and educational self-exclusion in secondary school. Men and Masculinities, 11(4), 462–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X06298780

Major, B. (1979). Sex-role orientation and fear of success: Clarifying an unclear relationship. Sex Roles, 5(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00289346

Mandal, E., & Moroń, M. (2019). Contingencies of self-worth and global self-esteem among college women: The role of masculine and feminine traits endorsement. Social Psychological Bulletin, 14(3), e33507. https://doi.org/10.32872/spb.v14i1.33507

Markland, D. (2007). The golden rule is that there are no golden rules: A commentary on Paul Barrett’s recommendations for reporting model fit in structural equation modelling. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 851–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.023

Martin, A. J., & Marsh, H. W. (2003). Fear of failure: Friend or foe? Australian Psychologist, 38(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060310001706997

Martin, C. L., Ruble, D. N., & Szkrybalo, J. (2002). Cognitive theories of early gender development. Psychological Bulletin, 128(6), 903–933. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.903

Matud, M. P., López-Curbelo, M., & Fortes, D. (2019). Gender and psychological well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(9), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193531

Maxwell, S. E., & Cole, D. A. (2007). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23

McClelland, D. C., Atkinson, J., Clark, R., & Lowell, E. (1953). The achievement motive. Appleton-Century-Croft.

McGeown, S. P., & Warhurst, A. (2020). Sex differences in education: Exploring children’s gender identity. Educational Psychology, 40(1), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2019.1640349

Moore, J. S. B., & Smith, M. (2018). Children’s levels of contingent self-esteem and social and emotional outcomes. Educational Psychology in Practice, 34(2), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2017.1411786

Morris, E. W. (2008). Rednecks, rutters, and rithmetic: Social class, masculinity, and schooling in a rural context. Gender and Society, 22(6), 728–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243208325163

Myers, D., Abell, J., Kolstad, A., & Sani, F. (2010). Social psychology. McGraw Hill.

Orlofsky, J. L., & Stake, J. E. (1981). Psychological masculinity and femininity: Relationship to striving and self-concept in the achievement and interpersonal domains. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 6(2), 218–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1981.tb00409.x

Otterpohl, N., Steffgen, S. T., Stiensmeier-Pelster, J., Brenning, K., & Soenens, B. (2020). The intergenerational continuity of parental conditional regard and its role in mothers’ and adolescents’ contingent self-esteem and depressive symptoms. Social Development, 29(1), 143–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12391

Pajares, F., & Valiante, G. (2001). Gender differences in writing motivation and achievement of middle school students: A function of gender orientation? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26(3), 366–381. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2000.1069

Piché, C., & Plante, C. (1991). Perceived masculinity, femininity and androgyny among primary school boys. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 6(4), 423–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03172775

R Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria. https://www.r-project.org/

Radziwiłłowicz, W., & Macias, M. (2014). Self-esteem and achievement motivation level in overweight and obese adolescents. Health Psychology Report, 2(2), 132–143. https://doi.org/10.5114/hpr.2014.43920

Reiss, K., Sälzer, C., Schiepe-Tiska, A., Klieme, E., & Köller, O. (2016). PISA 2015. Eine Studie zwischen Kontinuität und Innovation [PISA 2015. A study between continuity and innovation]. Münster; New York: Waxmann.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5-12 (BETA). Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2008). The social psychology of gender: How power and intimacy shape gender relations. Guilford Press.

Schöne, C., & Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. (2016). Selbstwertinventar für Kinder und Jugendliche – SEKJ [Self-esteem inventory for children and adolescents]. Göttingen: Hogrefe. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3583.5607

Schöne, C., Tandler, S. S., & Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. (2015). Contingent self-esteem and vulnerability to depression: Academic contingent self-esteem predicts depressive symptoms in students. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1573. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01573

Severiens, S., & Dam, G. T. (1998). A multilevel meta-analysis of gender differences in learning orientations. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 68(4), 595–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1998.tb01315.x

Sharpe, M. J., Heppner, P. P., & Dixon, W. A. (1995). Gender role conflict, instrumentality, expressiveness, and well-being in adult men. Sex Roles(1–2), 33, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01547932

Smiler, A. P. (2004). Thirty years after the discovery of gender: Psychological concepts and measures of masculinity. Sex Roles, 50(1–2), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SERS.0000011069.02279.4c

Smiler, A. P. (2006). Living the image: A quantitative approach to delineating masculinities. Sex Roles, 55(9–10), 621–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9118-8

Spence, J. T., & Helmreich, R. L. (1980). Masculine instrumentality and feminine expressiveness: Their relationships with sex role attitudes and behaviors. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 5(2), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1980.tb00951.x

Spence, J. T., Helmreich, R. L., & Stapp, J. (1974). The personal attributes questionnaire: A measure of sex role stereotypes and masculinity-femininity. University of Texas.

Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., & Bentler, P. M. (1992). The effect of agency and communality on self-esteem: Gender differences in longitudinal data. Sex Roles, 26(11–12), 465–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00289869

Steinmayr, R., & Kessels, U. (2017). Good at school = successful on the job? Explaining gender differences in scholastic and vocational success. Personality and Individual Differences, 105, 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.09.032