-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Joseph A Hafer, Developing the Theory of Pragmatic Public Management through Classic Grounded Theory Methodology, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Volume 32, Issue 4, October 2022, Pages 627–640, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muab050

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Public administration scholars argue that further research is needed to understand ordinary day-to-day behaviors of the traditional government agency in the era of inter-organization collaboration and governance, including reconciling traditional bureaucratic management theories with modern-day cross-sector governance theories. I answered this call by utilizing classic grounded theory methodology to discover and theorize the latent patterns of behavior of such an agency—the Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry—via the perspective of public managers. The primary source of data was unstructured interviews with 55 district and assistant district managers from the Bureau, and two interviews with executive directors of statewide nonprofits that frequently engage with the districts. Following the systematic processes of classic grounded theory methodology, I developed a theory called the Theory of Pragmatic Public Management that consists of the core category of Mission-driven Management, its four sub-core categories (Balancing, Advocating Value, Adapting to Uncertainty, and Prudent Collaboration), and two contextual conditions in the form of organization dynamics that impact the system (Organizational Capacity and Organizational Discretion). The theory is a modifiable and transferable theory that entwines traditional intra-organization management and inter-organization collaborative public management behaviors and relies on pragmatist thought for additional conceptual integration. It informs existing public management research that focuses on the day-to-day behaviors of public managers and offers practical insights on public management in the contemporary era of governance.

In contemporary public administration it is a rarity for a single, traditional government agency to be solely responsible for addressing a public policy problem. Instead, interorganizational collaboration has become the norm and involves working alongside actors external to these agencies (Frederickson 1999). Research has followed suit and there has been a shift from understanding how traditional government agencies deliver public goods and services to how “…more and more actors enter the public stage to carry out government functions and programs” (Agranoff 2017, 2). Some scholars contend that the traditional government agency is still a central actor (Frederickson et al. 2015; Meier 2010; van Dorp and ’t Hart 2019); but its role in this era of collaboration and governance is not entirely clear (Agranoff 2017; Cigler 2001; van Dorp 2018).

Collaborative public management (CPM) is often used to capture this shift away from traditional government, and encapsulates collaboration-focused areas of study, notably networks, civic engagement, collaborative governance, and cross-sector collaboration (Meek 2021). Scholars suggest that studying the lived experience of public managers will aid in reconciling traditional intra-organization management with inter-organization CPM (Bartelings et al. 2017; Frederickson et al. 2015; van Dorp 2018). In agreement with such, in this study I used classic grounded theory (CGT) methodology (Glaser 1998) to collect, analyze, and theorize patterns of behavior in the day-to-day life of a traditional government agency (i.e., the Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry). Recent efforts to systematically collect and analyze data related to such behavior are limited (particularly within the public sector), but some efforts have been made (Korica, Nicolini, and Johnson 2017).

Based on the findings of the research, I developed a theory called Pragmatic Public Management—a modifiable and transferable theory based in grounded empirical data that entwines traditional intra-organization management and inter-organization CPM behaviors of a traditional government agency in the era of collaboration and governance. The theory is comprised of multiple conceptual categories of such day-to-day behaviors, prominent properties of the categories, and theorizes the nature of the relationships between the categories. Pragmatist thought—particularly the position of anti-dualism—assists with conceptual integration of the categories and raises the conceptual level of the theory. This research informs existing research in public management that explores day-to-day behaviors of public managers to understand their role in governance (O’Leary and Vij 2012; van Dorp 2018).

In the next section, I frame the study problem and research question using literature that focuses on understanding the connection between intra-organization management and inter-organization CPM. Despite Glaser (1998) being a strong proponent of reviewing no literature related to the substantive area under study prior to beginning the study, many grounded theory researchers are skeptical of the ability to enter a grounded theory study with a complete blank slate (Suddaby 2006); thus, I conducted a broad preliminary literature review prior to research frame the study and direct initial theoretical sampling (Giles, King, and de Lacey 2013). Following this framing, I provide a brief synopsis of CGT methodology and its use in public administration literature given the confusion surrounding grounded theory methodology (Suddaby 2006). The remaining sections include the methodology, the findings of the research accounted through the theory developed, and a discussion that elaborates the theory and highlights contributions and limitations. Supplementary appendix provides additional detail on the methodology and the developed theory.

Problem and Research Question

Inter-organization management in public administration is often referred to as CPM, understood as “the process of facilitating and operating in multi-organizational arrangements to solve problems that cannot be solved, or solved easily, by single organizations” (Agranoff and McGuire 2003, 4). Such a process requires collaboration across multiple agencies within the same layer of government, with agencies at different layers of government (Mullin and Daley 2010), with private and nonprofit organizations (Bryson, Crosby, and Stone 2006), and with citizens directly (Nabatchi, Sancino, and Sicillia 2017).

A surge in CPM and collaboration-related research that has reflected the change in public administration practice and has created a substantial body of knowledge. For example, it has produced multiple collaborative governance frameworks (e.g., Ansell and Gash 2008; Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh 2012; Koontz 2006) and collaboration typologies (e.g., Cigler 2001; Keast et al. 2004; Margerum 2008). It has also expounded upon numerous concepts that are essential to collaborative endeavors, such as leadership (Silvia 2011), trust (Calanni et al. 2014), and antecedent conditions to collaboration (Chen 2010).

Recent, but largely separate, research suggests that efforts to better understand traditional intra-organization management have waned in the wake of CPM (Favero, Meier, and O’Toole 2016); however, there are advances in understanding how such management relates to organization performance and its relationship to transformational leadership. In the field of education administration, O’Toole and Meier (2011) demonstrated the relationship between organization performance and managing organization stability via personnel, attracting and developing human capital, and managerial decisiveness to buffer external shocks. Additionally, Favero et al. (2016) demonstrated how four core “internal” public management practices lead to better organization performance, such as how setting clear and challenging goals encourages employees to address organization problems. Such findings are similar to that of recent research on transformational leadership in public organizations—goal-oriented leadership motivates employees and improves productivity toward achieving that goal (Jacobsen and Andersen 2015; Wright, Moynihan, and Pandey 2012); and motivation generated through such leadership is linked to project success in public projects (Fareed and Su 2021).

Additional insight on traditional intra-organization management has been accumulating through a recent “trickle of research” (van Dorp and ’t Hart 2019, 878) that focuses on identifying systemic patterns of day-to-day managerial behavior via the perspective of the manager (O’Leary and Vij 2012). In other words, “what administrators are actually doing” in the era of governance (Frederickson et al. 2015, 247). For example, van Dorp (2018) conceptualized Dutch city managers daily behaviors in a vertical (i.e., internal to organization) versus horizontal (i.e., external to organization) system of logic; Bartelings et al. (2017) discovered that much of the work of Dutch public managers in public safety and healthcare aligned with classic managerial work á la Mintzberg’s (1973) framework but also included “orchestrational” tasks across inter-organizational networks (e.g., bridging); and van Dorp and ‘t Hart (2019) uncovered how top public administration officials carry out crafted practices of responsiveness and astuteness to address the classic politics-administration dichotomy.

Despite the growing bodies of knowledge in CPM and intra-organization management, scholars argue that there is a need for further research that reconciles traditional bureaucratic management theories with modern-day cross-sector governance theories (Bartelings et al. 2017; Frederickson et al. 2015; van Dorp 2018); particularly in “other institutional and organizational fields” in the public sector, such as outside of a European context. (van Dorp and ’t Hart 2019, 357). Additionally, there is a need to understand how the normative ideal of collaboration compares to the reality of day-to-day public service delivery (Sancino and Jacklin-Jarvis 2016).

This leads to the research question guiding the study: what are the ordinary day-to-day behaviors of the Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry in the era of collaboration and governance, and what are those behaviors’ prominent properties and influential contextual factors? Korica et al. (2017) suggest that using open-ended approaches that do not preclude the results to fall within existing dominant models aids in understanding day-to-day managerial work. CGT methodology is one such approach and was utilized in this study to address the research question.

Synopsis of CGT

The term “grounded theory” is often met with confusion as it is used to describe a way to conduct research as well as the product of that research (i.e., a grounded theory). Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss founded grounded theory methodology during their research on dying in American hospitals (Glaser and Strauss 1965), and detailed it in their seminal book The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (Glaser and Strauss 1967). Grounded theory has evolved since Discovery and is commonly categorized of into three approaches: Straussian grounded theory, constructivist grounded theory, and CGT (Kenny and Fourie 2014). All three approaches are rooted in Discovery—such that they are a method to generate empirically grounded theory—but there are differences in the approaches to implementing the method, the researcher’s position in the study, and the understanding of the data used (among other aspects).

CGT methodology is “the systematic generation of theory from data that has itself been systematically obtained” (Glaser 1978, 2). CGT consists of multiple systematic processes that a researcher conducts in an iterative fashion to produce a new theory grounded in empirical data. In other words, a new “grounded” theory is generated from the ground up. The new grounded theory produced is a substantive grounded theory, which can describe, explain, and predict but remains limited to the substantive area of inquiry (Holton and Walsh 2017). A researcher can also begin the process of moving the substantive grounded theory to formal grounded theory—a substantive grounded theory that has applicability across contexts and settings—by theorizing and documenting how the substantive grounded theory developed has potential application beyond the substantive area of study (Glaser 1998). Developing a fully developed formal grounded theory is beyond the scope of a single study.

The idea of emergence is fundamental to the systematic and iterative data collection (i.e., theoretical sampling) and data analysis (i.e., constant comparative analysis) processes within CGT. Emergence is the idea the researcher does not force his or her preconceptions (or academic interests) onto the data and instead allows those in the empirical setting to demonstrate what social phenomena is important (Holton and Walsh 2017). The empirical setting is referred to as the substantive area, which is “…an area of interest, not a professionally preconceived problem” (Glaser 1998, 118).

CGT is guided by the discovery of the main concern (i.e., the issue or problem that is at the center of the action in the substantive area), conceptual categories (i.e., primary variables that address the main concern of the individuals being studied) and category properties (i.e., primary characteristics of the conceptual categories) that emerge from the empirical setting of the study, and not by preconceived notions of the researcher (Glaser 1998).

In the following Methodology section, I provide a summarized account of how I implemented CGT to develop a substantive grounded theory. Additional detail on the methodology and resulting theory that demonstrates the full rigor of the study (Nowell and Albrecht 2019) is found in the supplementary appendix.

Methodology

Research Design

I followed a CGT research design, utilizing the processes of theoretical sampling, constant comparative analysis, open and theoretical coding, memoing, and theoretical sorting. I chose CGT methodology for this study for multiple reasons. First, adhering to CGT methodology ensures a substantial level of objectivity when conducting inductive research, where the researcher acts as a tool of interpretation and has influence on the outcome of the research. Second, Straussian and constructivist approaches to grounded theory are more stringent than CGT in terms of their approach toward and interpretation of data, which I believe is counterintuitive to exploratory, inductive theory development. Lastly, CGT is well suited to studying public administration—the theory that is produced links well to practice as it is grounded in a substantive area (Locke 2001).

Research Setting

The research setting is the Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry (the Bureau) of the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR). I selected the Bureau because it is a traditional government agency with substantial administrative authority and discretion; and the nature of the work of the Bureau (e.g., managing public land that is open to various forms of public use) requires collaborating with individuals and organizations outside of traditional agency boundaries. Additionally, state forestry is an under-studied public service—forest systems within the United States receive less scholarly attention than forest systems in other areas of the globe (Dartmouth College 2017); and research tied to US forest systems generally focuses on the federal level (i.e., National Forests and the US Forest Service), with much less focus on forest governance at the state level (Koontz 2007).

The Bureau is responsible for the approximately 2.2 million acres of Pennsylvania state-owned forest land and provides multiple conservation-related support services to private forest landowners throughout the state. The operating budget of the Bureau in 2016 was approximately $65 million, with nearly 90% of the budget being generated from resource management activities on state forest land (i.e., timber sales and oil and gas lease royalties; DCNR 2017). The Bureau is organized into a central office located in the state capital and 20 forest district offices. The central office includes the State Forester’s Office—the head office of the Bureau responsible for coordinating overall operations—and multiple Bureau divisions which provide support for various district forest operations (e.g., forest health, service foresting). The entire state is portioned into 20 forest districts with a district office located in each district. The district offices are responsible for administering Bureau policy and programs on the ground within their district. One District Forester (District Manager) provides oversight of each district, and typically has two Assistant District Foresters (Assistant District Managers). Varying numbers of foresters and technicians report to the Assistant District Foresters depending on the size of the district, which vary in size of coverage of the state and in the acreage of state forest land within their district (DCNR 2017).

Researcher Position

Practicing reflexivity is necessary to identify how personal influence may have introduced preconceptions into the study (Nowell and Albrecht 2019). My personal interest in selecting the Bureau as my substantive area of study is because I study subnational government agencies, and particularly how they implement policy that involves interactions with citizens and nongovernmental organizations. I am also personally intrigued by environmental policy in general but have had little experience with forest management prior to conducting this study. Glaser (1998) views this lack of prior experience with the substantive area as being beneficial to the researcher’s theoretical sensitivity and the study itself—my lack of knowledge of forest management limited my preconceptions of what to expect as the important action that was occurring in the substantive area, which in turn improved the emergence process.

While CGT methodology is considered “a-philosophical” (Glaser 2005), this does not infer that a researcher’s worldview will have no impact on the research to some extent (Holton and Walsh 2017). As a researcher, I tend not to subscribe to a single philosophical perspective and believe that adopting a single perspective restrains a researcher’s ability to explore and explain complex social phenomena. Given this, my worldview aligns well with pragmatism’s pluralistic and evolutionary position on what constitutes knowledge—it is temporary and will be surpassed by other knowledge sometime in the future. A pragmatic approach to inquiry and research is not a commitment to any single methodological approach (Hothersall 2018).

Data Collection and Analysis and Theory Shaping

Data collection and analysis was a nonlinear, iterative process. The primary data collection method was qualitative interviews with Bureau District and Assistant District Managers. Interviews with individuals knowledgeable and experienced in the substantive area are a common method to collect a wealth of rich data to start a CGT study (Holton and Walsh 2017). I included the two managerial ranks (District and Assistant) to ensure I captured the full scope of managerial behavior within the district and to increase the breadth of data collected, as there are only 20 District Managers.

I conducted 57 interviews split into four rounds over 7 months’ time. Twenty interviews were with district managers, 35 with assistant district managers, and 2 with executive directors of statewide nonprofits that frequently engage with the districts. Most of the interviews (52) were conducted in-person. Ten of those conducted in-person were conducted at a statewide Bureau manager’s meeting. The remaining 42 were conducted at district offices and nonprofit organization offices. Five interviews were conducted via telephone due to scheduling conflicts. The length of the interviews ranged from 20 min to slightly over 1 h, with most interviews lasting between 30 and 40 min. I conducted the interviews in an informal and conversational style, which facilitated a friendly and welcoming tone for open discussion.

I utilized open-ended, “grand tour” questions in initial interviews that facilitated open discussion, with interviews going in different topical directions (Simmons 2011)—questions such as “Tell me about your job at the Bureau of Forestry—what takes up most of your day?” and “How do you handle difficult forest management situations that arise?”. In accordance with theoretical sampling, I modified my interview questions to explore emerging topics and concepts that were based in initial data collection, both during interviews and in subsequent interviews (Holton and Walsh 2017). These modifications were used to gather data that was focused on the emerging main concern and core category of the study.

I did not require an interviewee to agree to audio recording to participate in the interviews, but 36 participants that were asked allowed audio recording. Of the remaining 21 interviews that were not recorded, 5 were telephonic interviews, 2 interviewees requested not be recorded, and the remaining 14 I did not record to obtain interview data where a recording device was not present to ensure consistency in responses with those that were recorded. I also took hand-written field notes for all interviews both during and after the interviews.

All interviews that I audio recorded were transcribed and coded using ATLAS.ti (Scientific Software Development GmbH 2016). Through line-by-line open coding, I discovered incidents—“indictors of phenomena or experiences as observed or articulated in the data” (Holton and Walsh 2017, 77)—that I coded with descriptive codes—description of what is going on in the incident—and analytic codes—conceptualizing what is happening in the incident. A table of example incidents as direct quotations from interview data (i.e., portions of transcribed interview text) is provided in the supplementary appendix.

Once the main concern, core conceptual category, and related sub-core conceptual categories emerged (see Findings) I switched to selective coding in accordance with theoretical sampling, whereby I restricted my coding to identify category properties, since not all data that were part of the interviews were relevant to the categories of interest (Holton and Walsh 2017). I conducted the same coding and analysis process for field notes for interviews that were not recorded. I conducted constant comparative analysis throughout coding to confirm and disconfirm the data and to increase theoretical saturation of categories and their properties.

The first round of interviews produced preliminary evidence of two conceptual categories (e.g., balancing diverse duties), but the main concern was still not clear and there was not enough data to substantiate a substantive grounded theory. The second round of interviews produced substantial insight on the main concern and how most of the action in the substantive area could be tied back to addressing the main concern via a core conceptual category. Additionally, two emerging conceptual categories from the first round were confirmed, and their properties were becoming saturated (i.e., no new data was being presented); and two additional conceptual categories emerged based on constant comparative analysis of data within and between rounds of interviews. However, further theoretical saturation was required. The third round of interviews produced data that supported a theoretical model with a single core category, four sub-core categories, and two related categories. I felt that the model and supporting data was adequate, but I decided to conduct a final round of interviews to further saturate the model and category properties. These were completed without audio recording to validate the data I was receiving during audio recorded interviews, as some scholars are skeptical of data received during audio recorded interviews (Glaser 1998). No additional concepts or novel elaborations of the existing concepts emerged, so I was satisfied with the theoretical saturation of the model.

I also implemented an intercoder agreement process to provide a check on my idiosyncratic biases (see supplementary appendix for additional detail). While such techniques are not prevalent in existing CGT research, I incorporated the check into the study to increase the reliability of the findings. I followed the process of Campbell et al. (2013) to account for the problems of discriminant capability and unitization related to qualitative interview data. A 10% random sample of interviews (six interview transcriptions) was selected. Following a negotiated agreement process between me and another coder—a post-coding discussion between coders to compare coding and resolve as many discrepancies as possible (Campbell et al. 2013)—an 83.9% level of agreement between me and another coder was obtained. Qualitative methods scholars have suggested that an 80 percent level of agreement between coders is acceptable (Campbell et al. 2013; Creswell 2014; Lens 2009).

Bureau documents served as a secondary data source. Data collected from these sources followed theoretical sampling (i.e., it was driven by the emergent main concern and core categories; Locke 2001). The unit of analysis for this data was at the organizational level (i.e., the Bureau). It was used to inform the context of the substantive area and to inform and authenticate the primary data, which was the individual-level interview data collected from managers. While the unit of analysis of the interviews was at the individual level, following CGT methodology the data was aggregated via constant comparative analysis and raised to a conceptual level to explain what was happening in the substantive area (i.e., the level of the organization; Glaser 1998). While there are inherent tensions in this process—collecting individual level data and theorizing it to the level of organization (Klein and Kozlowski 2000)—maintaining a consistent unit of analysis is most important in experimental or statistical research, and less of a concern in research that focuses on “situations and settings” such as in the present study (Haverland and Yanow 2012, 403). Additionally, such theorizing is common practice in CGT (Glaser 1998).

I enhanced data analysis and theory development through memoing—“…the theorizing write-up of ideas about codes and their relationships as they strike the analyst” (Glaser 1978, 83)—throughout data collection and analysis. I documented memos—by hand subsequently stored in ATLAS.ti—whenever I was struck with an idea about codes and categories of the study. Memos ranged in length from single broken sentences to several sentences explain complex theoretical ideas related to the data.

Theory integration and shaping was accomplished through constant comparative analysis, theoretical coding, and theoretical sorting (Glaser 1998). Integration of data through constant comparative analysis is best illustrated through an example—the coding evolution and arrival at the sub-core category Prudent Collaboration. For example, I used an initial descriptive code called “user group” in reference to a quotation mentioning different groups of persons using state forest lands. When comparing these coded quotations with others, I discovered that many times the quotation indicated collaboration of some nature between the user group and the Bureau, so I co-coded these quotations with a higher-order code called “collaboration”. When making further comparisons, I noted that different forms of collaboration were evident and coded quotations with “Collaboration-form-citizens” and “Collaboration-form-organization”. Further comparisons also evidenced different purposes for the collaboration, such as those that focus on joint land management and those that focus on joint research. I further coded the differences in collaboration purpose when discovering additional purposes through comparisons. The codes of form and purpose were able to conceptually capture most of the quotations that were coded with collaboration, thus they earned their way to being prominent properties of Prudent Collaboration (see supplementary appendix for additional detail).

Theoretical coding and sorting were used to integrate the emergent conceptual categories into a theory. I enhanced my theoretical sensitivity by reviewing the application of multiple theoretical codes used in other CGT studies (Glaser 1998). Multiple theoretical codes were applied to the data in conjunction with theoretical sorting with the goal of “…find[ing] the emergent fit of all ideas so that everything fits somewhere with parsimony and scope and with no relevant concepts omitted” (Holton and Walsh 2017, 109). This process included modeling relationships between all conceptual categories in different manners, such as modeling as a basic social process, the most common theoretical code (Glaser 1978). While the data were stored in ATLAS.ti, the theoretical sorting and modeling was conducted by hand to easily model potential theoretical relationships. Modeling the emergent conceptual categories using the system-parts theoretical code provided the most parsimonious theoretical model and resulted in the final substantive grounded theory that accounted for most of the behavior (i.e., data) within the substantive area that addressed the main concern. The findings in the following section detail this model in full.

Findings

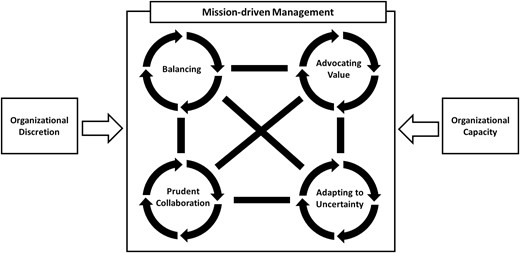

Following CGT methodology, the main finding of the research is the development of a substantive grounded theory based in the broad research question—what are the ordinary day-to-day behaviors of a traditional government agency in the era of collaboration governance, and what are those behaviors’ prominent characteristics and influential contextual factors? The theory developed is called the Theory of Pragmatic Public Management (table 1 and figure 1). It is grounded in the main concern and conceptual categories that emerged from the data collection and analysis.

Outline of the Theory of Pragmatic Public Management

| Name . | Level of Conceptualization . |

|---|---|

| Mission-driven Management | Core category |

| Balancing | Sub-core category |

| Multiple role sets | Property of Balancing |

| Stakeholder demands | Property of Balancing |

| Advocating Value | Sub-core category |

| Direct advocacy (formal and informal) and Indirect advocacy | Property of Advocating Value |

| Personal belief in organizational value | Property of Advocating Value |

| Complexity of value delivery | Property of Advocating Value |

| Adapting to Uncertainty | Sub-core category |

| Social and ecological challenges | Property of Adapting to Uncertainty |

| Managerial skills | Property of Adapting to Uncertainty |

| Seasonality | Property of Adapting to Uncertainty |

| Prudent Collaboration | Sub-core category |

| Form | Property of Prudent Collaboration |

| Purpose | Property of Prudent Collaboration |

| Organizational Capacity | Related category (contextual condition) |

| Organizational Discretion | Related category (contextual condition) |

| Name . | Level of Conceptualization . |

|---|---|

| Mission-driven Management | Core category |

| Balancing | Sub-core category |

| Multiple role sets | Property of Balancing |

| Stakeholder demands | Property of Balancing |

| Advocating Value | Sub-core category |

| Direct advocacy (formal and informal) and Indirect advocacy | Property of Advocating Value |

| Personal belief in organizational value | Property of Advocating Value |

| Complexity of value delivery | Property of Advocating Value |

| Adapting to Uncertainty | Sub-core category |

| Social and ecological challenges | Property of Adapting to Uncertainty |

| Managerial skills | Property of Adapting to Uncertainty |

| Seasonality | Property of Adapting to Uncertainty |

| Prudent Collaboration | Sub-core category |

| Form | Property of Prudent Collaboration |

| Purpose | Property of Prudent Collaboration |

| Organizational Capacity | Related category (contextual condition) |

| Organizational Discretion | Related category (contextual condition) |

Outline of the Theory of Pragmatic Public Management

| Name . | Level of Conceptualization . |

|---|---|

| Mission-driven Management | Core category |

| Balancing | Sub-core category |

| Multiple role sets | Property of Balancing |

| Stakeholder demands | Property of Balancing |

| Advocating Value | Sub-core category |

| Direct advocacy (formal and informal) and Indirect advocacy | Property of Advocating Value |

| Personal belief in organizational value | Property of Advocating Value |

| Complexity of value delivery | Property of Advocating Value |

| Adapting to Uncertainty | Sub-core category |

| Social and ecological challenges | Property of Adapting to Uncertainty |

| Managerial skills | Property of Adapting to Uncertainty |

| Seasonality | Property of Adapting to Uncertainty |

| Prudent Collaboration | Sub-core category |

| Form | Property of Prudent Collaboration |

| Purpose | Property of Prudent Collaboration |

| Organizational Capacity | Related category (contextual condition) |

| Organizational Discretion | Related category (contextual condition) |

| Name . | Level of Conceptualization . |

|---|---|

| Mission-driven Management | Core category |

| Balancing | Sub-core category |

| Multiple role sets | Property of Balancing |

| Stakeholder demands | Property of Balancing |

| Advocating Value | Sub-core category |

| Direct advocacy (formal and informal) and Indirect advocacy | Property of Advocating Value |

| Personal belief in organizational value | Property of Advocating Value |

| Complexity of value delivery | Property of Advocating Value |

| Adapting to Uncertainty | Sub-core category |

| Social and ecological challenges | Property of Adapting to Uncertainty |

| Managerial skills | Property of Adapting to Uncertainty |

| Seasonality | Property of Adapting to Uncertainty |

| Prudent Collaboration | Sub-core category |

| Form | Property of Prudent Collaboration |

| Purpose | Property of Prudent Collaboration |

| Organizational Capacity | Related category (contextual condition) |

| Organizational Discretion | Related category (contextual condition) |

Conceptual Model of the Theory of Pragmatic Public Management.

The main concern that emerged was the ability of the Bureau employees to manage Pennsylvania forest lands—both state- and private-owned—for long-term sustainability. In other words, to effectively govern a common-pool resource so that future generations may also benefit from and experience the resource. The resolution of the main concern is through identified patterns of behaviors of public managers and their employees (i.e., the core and sub-core categories) that accounted for most of the behavior in the substantive area. The theoretical integration between the core and sub-core categories of relies on the system-parts theoretical code—described as “the relation between parts or subparts of parts to the behavior of the whole” (Glaser 2005, 27). The “system” in the theory is the core category—Mission-driven Management—and the “parts” are the four sub-core categories—Balancing, Advocating Value, Adapting to Uncertainty, and Prudent Collaboration. The system would not be whole without each part, as each part accounts for a substantial amount of action in the substantive area. The parts are not sequential; rather they are interactive, and it is not possible (nor necessary) to capture which part comes first. In other words, “…once the ball is rolling they feed on each other” (Glaser 1978, 76). The parts are conceptual categories of behavior that shape the representation of Mission-driven Management. In addition to the system and its parts are two related categories (i.e., contextual conditions) in the form of organizational dynamics that impact the system: Organizational Capacity and Organizational Discretion.

In the following subsections I detail the core category, sub-core categories, and related categories. They are illustrated using some of the empirically grounded incidents (i.e., direct quotations from interviews and evidence from secondary data sources). The number of incidents presented for each category or property is not a representation of the overall number of incidents in the study for that category or property (see supplementary appendix for additional detail). Instead, the incidents that are presented are those that I selected for having conceptual “grab” and for having clarity of representation (Glaser 1998).

Core Category: Mission-Driven Management

The main concern is resolved through the core category of Mission-driven Management, which conceptualizes how most of the action of an organization is driven to accomplish the organizational mission. This was evidenced by how the geographically dispersed forest districts demonstrated a consistent comprehension and application of the Bureau mission. For example, one manager noted:

Whether it’s a big project, whether it’s a small project, the improvements we make to better the system, to improve environmental impacts, in the long run are gonna show the constituents that yes, we are doing what our mission statements says in managing the resource. (Interview 33)

The Bureau’s mission statement aligns with resolving the main concern: “…to ensure the long-term health, viability, and productivity of the commonwealth’s forests and to conserve native wild plants” (DCNR 2018a). A primary aspect of the Bureau’s mission is to ensure future generations can use the commonwealth’s forest, thus taking a “long-term,” or sustainable, stance on resource management. Long-term sustainability is impacted by various district management operations, such as timber management, oil and gas management, and recreation management.

Many of the district and assistant district managers interviewed explicitly and implicitly noted how they are managing for sustainability. For example, one manager stated:

I’m managing the state forest for its long-term viability and sound ecosystem and it is what it is. I gotta do what I gotta do to ensure the long-term ecological viability of the system 50, 75, or 100 years from now. (Interview 36)

The focus of the Bureau’s mission statement on “the commonwealth’s forests” as a whole (i.e., not limiting to state-owned forests) relates to the Bureau’s role of educating private forest owners and the public about fire prevention and proper forest stewardship. The Bureau conducted about 900 forest fire prevention events per year from 2012 to 2016 across the commonwealth, which equates to about 14 events per county per year. In terms of promoting proper forest stewardship, in 2016 the Bureau recorded over 11,000 service foresting outreach activities across the commonwealth (e.g., forest planning assistance to private owners, street tree recommendations). In addition, the Bureau conducts education sessions for approximately 400 Early Childhood and Pre-K to grade 12 educators per year to teach them how to use trees and forests to increase their students’ understanding of the environment and conservation. These figures demonstrate that the Bureau directs substantial resources to ensuring long-term sustainability of all commonwealth forests.

The Bureau’s mission also mentions managing for forest “productivity.” The idea of productivity could apply to any of the many values of the forest, including ecological services (e.g., air purification), forest goods (e.g., timber), and sociocultural benefits (e.g., recreation). This coincides with sustainability—without keeping a resource sustainable, it is unable to be productive. Maintaining forest productivity was evidenced throughout the interviews with managers, particularly when discussing timber management. For example, one manager noted “We’re cutting to make a healthy forest, basically, a sustainable forest” (Interview 18). In addition, since 1998 the state forest system has achieved the Forest Stewardship Council’s Forest Management certification, which means that products produced with state forest timber “…come from responsibly managed forests that provide environmental, social, and economic benefits” (Forest Stewardship Council 2017).

Mission-driven management is accomplished through four conceptual categories of behavior—the sub-core categories of Balancing, Advocating Value, Adapting to Uncertainty, and Prudent Collaboration. Each are described in the following subsection. The categories are discussed separately but further analyses of the qualitative interview data (i.e., quotation co-occurrence and adjacency counts) indicated signals of linkages between the behaviors. Given article length constraints, these analyses and the associated theorizing of the linkages between the categories are provided in the supplementary appendix.

Sub-Core Categories

Balancing

Balancing conceptualizes the day-to-day struggle (and its resolution) that managers encounter when addressing a wide variety of tasks. Complete balance is never reached as ongoing demands and pressures require constant balancing between tasks. Bureau managers revealed that keeping state forest districts running smoothly requires wearing numerous “hats,” which includes diverse tasks, such as human resource management, timber management, planning for large scale recreation events, safety and enforcement, regulating campsites, maintaining trails, nurturing relationships with private landowners and surrounding communities, cleaning up after storms and fires, land acquisition, educating the public about conservation, long-term planning for sustainability, plant and wildlife inventory, addressing forest-user and stakeholder concerns, and controlling pests, invasive species, and diseases that jeopardize the forest.

Balancing can be conceptualized as an internal struggle when managers are required to balance between opposing role sets, defined as “structural properties of position” within an organization that include the “normative activities seen as roles associated with one position” (Glaser 1998, 172). There were two prominent opposing role sets of Bureau managers that emerged: a traditional role set that focuses on forest and land management (e.g., marking and selling timber, maintaining roads) and a modern role set that focuses on recreation management and public outreach (e.g., interacting with forest user groups, managing organized events). The traditional role set is increasingly being challenged by the modern role set. Organizational priorities are shifting, and managers are attempting to balance between these two role sets. This struggle is evidenced in the following quotation from one forest manager:

So, people are coming there to recreate, we’re trying to give them as good of an experience as we can with the staff we have. That’s one of the things we struggle with, to get our core work done which is, I consider, the roads and the timber. Those are really our core stuff, that’s the stuff that we got to get done first then as we have time, we try to do the recreation stuff. There’s a lot of recreation stuff we could be doing that we just don’t have time to do. Then we do a lot of public outreach too. We gotta tell our story, we gotta get people interested in the outdoors. We also build support publicly by letting people know what we do and being out there. (Interview 23)

Balancing can also be conceptualized as an external struggle of managers through the need to balance stakeholder demands. State forest lands have numerous stakeholders, including companies that contract to use state forest land for various reasons (e.g., timber companies, oil and gas companies, electric companies) and state forest land users (e.g., individuals, recreational groups, leased campsite holders). Forest managers receive multiple requests from stakeholders that can be overwhelming—“…this guy is asking if he can trim this power line over here, this storage guy wants to drill another injection well, the pipeline over here needs a pig launcher, oh this guy over here needs…” (Interview 21). Many of the requests also conflict with others—a frequent conflict being when a timber company wants to build a road across a certain stretch of forest to remove timber, which clashes with recreational groups by interfering with trails (e.g., hiking, equestrian, mountain biking) or disrupting hunting patterns.

Advocating Value

Advocating Value conceptualizes how managers and employees demonstrate the value that their organization provides to other organizations and the public. This is important to Mission-driven Management because individuals outside the organization are unlikely to support the mission-driven work of the organization if they are unaware of the value of the organization. This is particularly important for public-sector organizations, as they are accountable to the citizens they serve. With broader public support, public-sector organizations are likely to thrive—citizens have the ability to advocate on behalf of the organization, donate (time and money) to causes that support the organization, and reach out to political officials that influence the viability of the organization.

Managers demonstrate value through direct and indirect advocacy. Direct advocacy involves person-to-person engagement with individuals outside the organization to through both formal and informal channels. Formal direct advocacy is prominent in regular Bureau operations. For example, the Bureau has established public meetings where managers have a formal platform to educate the public about their District State Forest Resource Management Plan (DCNR 2018b). Another example of formal direct advocacy is the Service Forestry program, which involves foresters going into the local communities and educating private-forest landowners and the public about conservation, sustainable forest management, and the value of forest land. Many service foresters participate in community events, as is described by one forest manager:

We’re active in events that happen in like fairs, town festivals, you know, we have a trailer, public contact trailer that we manage, that we man. With information about state forest land and things you can do there. We tried that. It’s important. Stakeholder relations. I guess from a county, it’s important, but sometimes it can be overwhelming. I’d say we do more of it now than we ever have. (Interview 26)

Informal direct advocacy occurs through any irregular contact with individuals outside the organization. Forest managers encourage Bureau employees to engage with the public with the goal of educating them on an aspect of the forest in which the person is interested, or on an aspect with which the person is unfamiliar. For example, when loggers are working on a timber sale on state forest land the foresters will explain to the loggers why the Bureau does what it does to promote sustainable forestry. The idea is to pass sustainable forestry knowledge to the loggers who have the potential to influence sustainable management of private forest lands.

In contrast to direct advocacy, indirect advocacy conceptualizes the actions of managers that produces organizational output that displays the value of the organization; yet this output may not be perceived by the public. For example, forest managers advocate the value of forests by engaging in sustainable timber harvesting—the sale of timber offsets tax consumption that benefits citizens in the present; doing so sustainably ensures that citizens in the future will also be able to realize tax offsets through timber sales. Sustainable timber harvesting also promotes forest health, which contributes to effective carbon sequestration and water filtration; these are benefits citizens receive, but typically do not perceive. Another example is evidenced by the Bureau’s forest ranger law enforcement practices, patrolling and preventing individuals from damaging the resource, such as individuals riding ATVs illegally throughout the forest.

Managers use a mix of direct or indirect advocacy, influenced by manager’s stance on what work of the organization they believe is of most value to the public. In the case of the Bureau, this is evidenced through managers’ Balancing between traditional and modern role sets. Traditional forest managers tend to utilize indirect advocacy, serving as a silent steward of the forest. On the other hand, modern forest managers tend to utilize direct advocacy, serving as a public-engaging forest steward who values educating the public about forestry—“We gotta tell our story, we gotta get people interested in the outdoors; we also build support publicly by letting people know what we do and being out there” (Interview 23). Many forest managers that utilize direct advocacy used timber harvesting as an example of where education is useful to advocate value—ensuring that the public knows that the harvesting is done sustainably and when done alongside conservation produces value to the public.

Often the value an organization provides is not simple; particularly when the organization produces complex goods or provides multiple services. This complicates advocacy as individuals find value in some aspects of the organization while others find value in different aspects. Managers in these situations may struggle with determining when to advocate which value to which individual, which is evidenced in the Bureau. The value that the Bureau provides is the effective management of commonwealth forests, and forests have numerous values, from providing physical goods (e.g., timber) to providing personal well-being (e.g., peace and solitude).

The complexity of the system of public service delivery also hinders Advocating Value. For example, many forest managers indicated that the public confuses the Bureau with the Bureau of State Parks and the Game Commission. While the Bureau of Forestry and Bureau of State Parks are under the same Department, they have different missions and goals for serving the public. The Game Commission is an entirely separate state entity, with a different mission and organizational goals. All three entities have land that is in proximity and many times users do not recognize which government agency is responsible for which land. Without users knowing the appropriate organization for the land they are using, it is difficult for the user to associate the value they perceive with the appropriate organization. Users also remain ignorant of how that agency’s mission guides the management of that land.

Adapting to Uncertainty

Adapting to Uncertainty conceptualizes how managers respond to unexpected social and ecological challenges that confront the organization. This involves shifting resources from one area of focus to another based on the demands of the challenge. This can be detrimental to Mission-driven Management as it diverts resources from mission-driven tasks; but it can also be beneficial as it may force managers to reallocate resources back to mission-driven tasks.

Unexpected social challenges come in various forms. A prominent example is top-down political pressure, which generally involves a range of demands. Political pressure is particularly prominent in public organizations where political appointees and elected officials (both executive and legislative) can influence organizational operations. A forest manager from the Bureau describes how political influence impacts district forest operations:

Things are always changing and going to be different. We are influenced by political changes in Harrisburg. So new folks … you get a new governor, new secretary, they have new ideas and new initiatives. So, every four to 8 years, we’re kind of changing our focus so which means the staff has got to accept to meet the new initiatives and work that into their schedules. (Interview 46)

Unexpected challenges also come in the form of ecological events. For example, severe weather events are typically unpredictable (from a long-term perspective) and the impact they may have on an organization is unpredictable. Some events may be anticipated as being impactful but will result in little to no impact; and vice versa. Some events may result in substantial property damage or may restrict the ability of personnel to get to their work site, which requires adapting daily operations to respond to the event. Bureau operations are greatly impacted by weather events since the Bureau manages large land areas. One forest manager noted how a recent storm shifted operations:

We just talked about those big storms that came through here. We’re out looking at areas now to salvage because everything that was in some of these stands is now flat. And if you walk away from that, you’re not really doing your due diligence. (Interview 46)

Both social and ecological challenges require managers to have certain skills to be able to effectively adapt organizational operations to uncertainty. Three common skills emerged through the interviews with forest management: knowledgeable, flexible, and decisive.

Seasonality is a property of Adapting to Uncertainty that has the potential to offer stability amidst the uncertainty. Organizations vary in the level of stability that seasonality provides, but most organizations will have some operations or events that occur at specific times of the year (e.g., reporting, fundraising). Many organizations—including the Bureau—are impacted by the seasonality of the budget cycle. Several forest managers noted the need to expend certain funds by the end of the fiscal year or the funds will no longer be available. Similarly, the Bureau has a seasonal staffing cycle such that some Bureau employees do not work over the winter months. It is beneficial to be able to plan for this regular decrease in staffing.

Prudent Collaboration

Prudent Collaboration conceptualizes how managers tactfully incorporate collaborative relationships that cross organizational boundaries into the organization’s operations. Collaborative relationships are ubiquitous in the daily administrative life of an organization, but have substantial variation. Relationships can be conceptualized by their form (e.g., person-to-person, organization-to-organization, contractual, informal) and purpose (e.g., share resources, gain knowledge). Since collaborative relationships are based in social relations, they tend to be dynamic rather than static—the actors and conditions of the relationship will change. In Mission-driven Management, a manager’s decision to collaborate is influenced by how the manager perceives the collaborative relationship will help or hinder mission accomplishment. While some collaborative relationships may be mandated through top-down channels, manager’s make prudent decisions to encourage the relationship or to demote its importance. Manager’s that believe in the mission-importance of certain collaborative relationships will cultivate those relationships and seek out similar mission-supportive relationships in a prudent manner.

Collaborative relationships are evidenced throughout each forest district of the Bureau. Many relationships are ingrained as part of day-to-day life and are crucial for meeting the Bureau mission—“I just can’t speak enough about our partnerships and how critical they are to the overall operations of the district” (Interview 20). The relationships vary substantially in terms of form and purpose within and across districts. Districts collaborate with a range of other organizations in an informal manner, such as other Pennsylvania state agencies (e.g., Bureau of State Parks), federal agencies (e.g., US Forest Service), local nonprofits (e.g., County Conservation Districts), local governments, and universities. The purpose of these collaborative relationships is often based in conducting different types of joint activities (depending on the relationship), such as recreation management, land management, public education, fire management, law enforcement, research, and wildlife management.

The collaborative relationship with Bureau of State Parks is one of the Bureau’s most prominent. Land management activities for both organizations include basic maintenance duties, so they frequently share manpower and equipment in an informal manner:

We’ve given parks some of … we got rid of some junk equipment they wanted because Parks doesn’t get good equipment. But we work close with them. In the winter, we plow [state park] and they plow a parking lot over in [state forest section]. It doesn’t make sense for us to drive 45 minutes past each other. So yeah, we share stuff. If they need something, they call us. If we have something over that way, a tree down, we’ve called them and they’ve gone out and taken care of it. We work hand in hand. I think it’s great. (Interview 28)

The districts also collaborate with other organizations in a formal manner, such as contractual relationships. These relationships are no less collaborative than noncontractual collaborative relationships as both parties involved benefit from the relationship. For example, the districts have contractual relationships with logging companies to cut and extract timber from state forest lands. Districts do not have the capacity to cut, extract, and sell their own timber to market, thus they utilize contractors. The district benefits by receiving monetary compensation for the timber to augment the Bureau budget. They also use timber sales to promote sustainable forest growth. Districts do not mark timber to be sold at random—the Bureau has achieved the Forest Stewardship Council’s Forest Management certification since 1998, which means that forest products “…come from responsibly managed forests that provide environmental, social, and economic benefits” (Forest Stewardship Council 2017). Contracted logging companies benefit from the relationship because they can brand their timber from state forest land as FSC certified, making it desirable to buyers.

Districts also have many collaborative relationships with individual volunteers and volunteer groups. Volunteers are typically frequent visitors of state forest lands and may be classified as part of certain user groups (e.g., hunters, hikers). Like contractual collaborative relationships, these relationships are symbiotic as both the user and the district benefit: the user can improve an aspect of the forest they personally use, and the time donated frees up manpower hours for the district. The relationships are generally small-scale, but the time individuals’ volunteer accumulates, and has become crucial to some districts.

Contextual Conditions

The Theory of Pragmatic Public Management also includes two contextual conditions in the form of organizational dynamics. These conditions impact the system and influence Mission-driven management. It is possible that additional organizational dynamics may impact Mission-driven Management, however these two dynamics were prominently grounded in the data.

Organizational Capacity

Organizational Capacity is conceptualized as how resource limitations within an organization shape the representation of Mission-driven Management. Resources are anything that contribute to accomplishing the organizational mission (e.g., materials, knowledge, personnel). For the Bureau, the most prominent organizational capacity limitation is the lack of personnel. Forest managers suggested that they would be better able to conduct proper forest management with additional personnel. For example, one forest manager stated: “With the reduction of staff over the years, it gets harder to keep up with the commitment that we basically honored for years” (Interview 25). This commitment refers to effectively managing state forest land on behalf of the public; however, the lack of maintenance staff negatively impacts the ability to maintain roads and trails; lack of rangers negatively impacts the ability to adequately monitor state forest land for illegal activity; and lack of foresters limits the ability to adequately conduct regular forest management activities (e.g., timber sales). One forest manager noted that both limited personnel and a limited budget negatively impacts the district’s ability to conduct outreach activities, which are core to Advocating Value:

We are a Monday through Friday organization for the most part with the exception of an emergency and those user groups are coming to recreate on the weekend, no matter the user group. Sometimes we have to have increased staffing or we have to have an increase presence whether it’s law enforcement or fire patrol, or state forest officer. General outreach, it’s tough on a limited budget and limited staffing. (Interview 27)

Additionally, limitations on Organizational Capacity—such as lack of personnel—lead to increases in Prudent Collaboration to meet the mission of the organization. In the case of the Bureau, this is evidenced by instances of coproduction—relying on citizens to assist with forest management.

Organizational Discretion

Organizational Discretion is conceptualized as how the bounds of decision-making authority throughout an organization shape the representation of Mission-driven Management. Organization charts display the supposed structure of authority and discretion, but the actual decision-making discretion at each level will not be evidenced. Discretion is more dynamic than a static organization chart and will vary based on the type of decisions and the actors at the different levels. In public sector organizations the dynamics of Organizational Discretion are impacted by the agenda of political appointees, and whether they will try to constrain or open decision-making authority across the organization.

While Organizational Discretion exists throughout all levels of an organization, it tends to feature prominently in some parts of the organization’s structure. For example, Organizational Discretion within the Bureau features most prominently when considering the relationships between the Bureau central office and the state forest districts. The central office has formal authority and oversight of the operations of the 20 forest districts (DCNR 2017); yet the districts are afforded substantial decision-making discretion in day-to-day operations. One forest manager described this as “there are 20 kingdoms [districts] and 20 different ways of doing every different thing we do” (Interview 22). Districts operate largely independent of the central office on a day-to-day basis and have the discretion to plan and carry-out forest management operations. Nonetheless, certain central office directives, particularly those that are politically driven, may get priority attention from the districts—“It depends on where the orders are coming from. If they’re coming down from Harrisburg, then we drop what we’re doing and we go take care of the issue. It just depends on the situation” (Interview 34). Yet the influence from the central office is also bounded, as districts receive pressure from the local environment (social and ecological) that demand attention.

Incorporating Pragmatist Thought into the Theory

After the core and sub-core categories emerged, I noticed how the integration of these categories and the conceptual level of the theory would be enhanced by viewing the theory through a pragmatist lens. Pragmatists embrace the position of anti-dualism by rejecting a winner-take-all position on the debate between rationalism and empiricism theories of knowledge, as well as rejecting contemporary dichotomies (Ansell 2011; Nathaniel 2011). The categories that emerged in the study illustrated a rejection of a dichotomy of managing a public good through the traditional government agency or through a cross-sector collaborative governance scenario. The data suggested a blend of the two. Thus, pragmatism earned its way into the theory by providing an overarching theoretical integration.

Additional aspects of pragmatist thought also enhanced parts of the developing theory. For example, Ansell (2011) describes a pragmatist perspective of organizations as one that encourages the “…the cultivation of organizational purpose through the development of a meaningful mission” to stimulate effective organizational operation (Ansell 2011, 16). Thus, organizations that enable Mission-driven Management—as driven by the four sub-core categories of behavior—may stimulate organizational effectiveness. Additionally, a pragmatist perspective encourages social inquiry and communication to gain insight into solving problems (Nathaniel 2011)—“walking in someone else’s shoes” and critical listening are elements that “…help to illuminate and deepen our understanding of our own and others’ beliefs, values, and interests” (Ansell 2011, 396). Through a pragmatist lens, Prudent Collaboration and Advocating Value are potential avenues to incite inquiry and dialogue about shared problem and value definition.

Incorporating pragmatist thought into the theory also links to and extends the concept of pragmatic municipalism, which suggests that public managers in local governments are strategically selecting service delivery methods and revenue sources to fit their context (Kim and Warner 2016). The theory developed here provides potential insight of public managers behaviors in local governments via the conceptual categories of Balancing and engaging in Prudent Collaboration. It also situates the concept of pragmatic municipalism in a broader, conceptual theory of public management.

Discussion

In summary, I utilized CGT methodology to develop a substantive grounded theory called the Theory of Pragmatic Public Management. The theory is based on the emergent main concern discovered in the Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry—the ability of the Bureau employees to manage Pennsylvania forest lands (both state- and private-owned) for long-term sustainability. I used the system-parts theoretical code (Glaser 1998) to integrate the data into a theory conceptualized as a core category of Mission-Driven Management as the “system,” with the “parts” consisting of the four sub-core categories of Balancing, Advocating Value, Adapting to Uncertainty, and Prudent Collaboration. These categories explain how the main concern is resolved and capture most of the ordinary day-to-day behaviors carried out by the Bureau. The system is impacted by two related categories conceptualized as contextual conditions: Organizational Capacity and Organizational Discretion. Overall theoretical integration was informed by pragmatist thought.

In the following subsections I discuss how the theory contributes to existing research along with practical contributions. I also discuss the transferability, credibility, and limitations of the research.

Contributions to Existing Research

The primary theoretical contribution of my study is the development of an original, substantive grounded theory called the Theory of Pragmatic Public Management. The theory informs existing research in public management that explores day-to-day behaviors of public managers to understand their role in governance (O’Leary and Vij 2012; van Dorp 2018). Such research has explored the dichotomy of inter-organization CPM and traditional intra-organization management but has done so via the application of existing frameworks. For example, by applying Mintzberg’s classic managerial roles and “orchestrational work” (i.e., CPM) to observed day-to-day behaviors of public managers (Bartelings et al. 2017), or by classifying intra-organization management as “up” and “down” and CPM as “out” (van Dorp 2018). However, the current study adds to this literature as it used a CGT methodology that did not presuppose existing theories or frameworks from either tradition onto the data (Korica et al. 2017). Thus, the grounded theory developed is not based in a dichotomous understanding, rather it is a blended perspective of public management—traditional intra-organization management and inter-organization CPM—in the era of governance and collaboration. This is evidenced by how Prudent Collaboration emerged as one of four sub-core categories of the theory and not as a sole core category that resolves the main concern. This suggests that CPM is a day-to-day concern of public managers, but it is not their primary focus. On a day-to-day basis they are also Balancing conflicting role sets, Adapting to Uncertain social and ecological challenges, and Advocating the Value of their agency and the public service being provided. Collaborative endeavors that support organizational mission accomplishment remain important to public managers, but only when these other behaviors are not dominating their time. Bartelings et al. (2017) assert that the “…separation line between traditional managerial work and orchestrational [network management] work was often blurred” (p. 357), which was confirmed by the findings in the present study, such that the four sub-core categories of behavior that emerged represent an entwinement of the two types of management driven by organizational mission accomplishment.

The theory also highlights how organizational level factors—conceptualized as Organizational Capacity and Organizational Discretion—continue to be influential in shaping public management focused driven toward mission accomplishment (Egeberg, Gornitzka, and Trondal 2016). Evidenced in the current study, due to Organizational Capacity limits Bureau managers are forced to allocate personnel to activities that are core to the mission of the Bureau (e.g., marking timber to sell, maintaining state forest roads) even if this pulls personnel away from activities that are mission-focused but are not as core (e.g., maintaining trails, attending school programs). An insightful direction for future research would be to explore how carrying out core-mission versus noncore-mission operations influences organization effectiveness.

While the theory developed in the present study does not (yet) directly relate to organizational effectiveness, it provides insight into the linkages of managerial behavior, organization mission, and organization effectiveness. Previous research suggests that clarity of the mission and acceptance of the mission by the organization’s members is linked to organizational effectiveness (Cheng 2016; Wright et al. 2012). The Theory of Pragmatic Public Management suggests that the four conceptual categories of behavior that comprise Mission-driven Management could enhance mission clarity and acceptance. Organization leaders that can effectively Advocate Value within the organization must clarify organizational goals and raise employee awareness of the importance and value of the organization to increase mission valence (Wright et al. 2012). Such leaders must also be afforded autonomy to make hiring decisions (i.e., they are not limited in their Organizational Discretion) to increase mission coherence (Cheng 2016). This also reiterates the work in transformational leadership in public administration that highlights the importance of goal-oriented leadership (Jacobsen and Andersen 2015) and supports the idea that a relational perspective of leadership may be linked to organization effectiveness as measured through mission accomplishment (Ali et al. 2021). Future research that operationalizes the four conceptual behaviors of the theory in measurable variables—such as through the development of psychometric scales (Robinson 2018)—would be a step forward in linking managerial behavior, organization mission, and organization effectiveness.

While the theory itself is of demonstrated value, the four sub-core categories of the theory individually inform other bodies of literatures. For example, the emergence of Prudent Collaboration suggests focusing on one form or purpose of collaboration without considering others does not reflect the empirical reality as substantial variation exists in form and purpose. Similarly, Williams (2016) suggests that the name given to various forms of collaboration within public administration is largely arbitrary and is a shortcoming of contemporary collaborative governance frameworks. As found in the present research, Bureau managers were working with single-volunteer coproduction to complex bid-based contracting, and everything in between. To provide value to practice, future research should focus on the entire picture of collaboration rather than on siloed types, including understanding how policy outcomes are impacted by different collaboration “mixes” in different contexts (Sancino and Jacklin-Jarvis 2016).

The study also has noteworthy methodological contributions. First, it demonstrates the value of utilizing the entire CGT methodology to develop conceptually rich theory in public administration and serves as an example of rigorous grounded theory research. Second, the use of CGT methodology adds variation to the body of qualitative research in public administration, which tends to be dominated by case study research (Ospina, Esteve, and Lee 2018). Increased variation better demonstrates the usefulness of qualitative research. Lastly, I demonstrated the value in using an established intercoder agreement process for qualitative interviews in public administration research. Increasing the use of a defined process improves research reliability and demonstrates researcher transparency (Luton 2010).

Practical Contributions

There are multiple practical contributions that are offered by the theory. First, affording managers substantial Organizational Discretion enables organizations to respond to demands from local stakeholders, which is particularly relevant for organizations that are geographically dispersed. Second, an Organizational Capacity limitation in the form of insufficient personnel limits managers’ ability to advocate the value of the organization. Being unable to adequately advocate value limits the ability of the organization to gain public support, which is particularly important for organizations that are accountable to the public. For organizations that provide multiple, complex values—such as both ecological and sociocultural benefits—it is particularly important for managers to understand which values are most important to which part of the public to assist with conveying the value of their organization. Third, Prudent Collaboration highlights the value of different types of collaborative relationships—ranging from formal bid-based contracting to individual volunteerism—to support different organizational operations and goals. Lastly, the theory highlights the importance of the written organization mission statement to day-to-day managing. Ensuring the mission statement is concise and understandable to employees will help inspire dedication to the organization (Goodsell 2011).

Theory Transferability

The conceptual level of the theory makes it transferable to organizations outside the substantive area (i.e., state forest management). Exploring the use of the theory in such cases increases the generalizability of theory (Silverman 2011) and begins the process of moving the theory from a substantive theory to a formal theory (Glaser 1998). Homeless services and corrections are two policy contexts where, at a descriptive level, day-to-day operations appear substantially different than forest management; yet through the conceptual lens of the theory one can see how the day-to-day operations may be similar. For example, in homeless services indicators of Balancing stakeholder demands will be discovered as a single organization typically serves as the convener of regional collaboratives and must balance the needs of diverse members (HUD Exchange 2020). For corrections, indicators of Mission-driven Management would be prominent as correctional institutions are organizations that are highly focused on accomplishing the organizational mission (Wakai et al. 2009). This is just a sample of the transferability of the theory with two policy contexts selected based on my previous research and practical experience (additional detail is found in the supplementary appendix); other policy contexts could also be selected.

Theory Credibility

There are four criteria to evaluate a CGT to determine if it has been developed with rigor and is a valid grounded theory of quality: the theory “fits” the pattern of data; the theory has “workability” in that the concepts in the theory account for the resolution of the main concern; the theory has “relevance” for the people in the substantive area; and the theory has “modifiability” such that it is flexible enough to encompass new data (Glaser 1998). My theory ensured the fit and workability by relying on constant comparative analysis, which improves data fit and keeps the researcher focused on the main concern in the substantive area (Glaser 1998). The intercoder agreement process also improved fit and workability by ensuring reliable data coding. Relevance was improved by expressing self-awareness of potential biases in my analytical memo writing; and relevance was demonstrated through examples of practical contributions noted earlier. Lastly, the theory I developed has modifiability as there is the ability to add additional conceptual categories of behavior (i.e., sub-core categories) and contextual conditions (i.e., related categories) to the theory.

Research Limitations

Subjectivity and personal biases impacting validity are a common concern in CGT research as the researcher is the primary operational tool (Hoflund 2013). I accounted for such by reflecting on CGT data analysis questions (e.g., “what is this a study of”) throughout the study. I also corroborated the data by collecting it from multiple managers within the same substantive area who have different personal perspectives and experiences (Creswell 2014; Hoflund 2013).

A second limitation is the reliability of the research, given replication of findings in qualitative research is difficult (Hoflund 2013). While intercoder agreement techniques are not prevalent in existing CGT research, I incorporated an established process (Campbell et al. 2013) into my study to enhance the reliability of my findings (Creswell 2014; Locke 2001).