Introduction

The global trade in wildlife is a highly lucrative industry that is driven by increasing demand in certain countries, with large volumes of wildlife and their derivatives being traded both internationally and domestically (Tingley et al. Reference Tingley, Harris, Hua, Wilcove and Yong2017, Symes et al. Reference Symes, McGrath, Rao and Carrasco2018, Di Minin et al. Reference Di Minin, Brooks, Toivonen, Butchart, Heikinheimo, Watson, Burgess, Challender, Goettsch, Jenkins and Moilanen2019). Birds are the most heavily traded taxa in the live animal industry (Bush et al. Reference Bush, Baker and Macdonald2014). Approximately one-third of global bird species are implicated in this trade (Nijman Reference Nijman2010, Ripple et al. Reference Ripple, Wolf, Newsome, Hoffmann, Wirsing and McCauley2017). While a portion of the global trade is legal and legitimate, much of the trade is illegal and underground in nature, preventing the efficient execution of enforcement and regulation measures (Haas and Ferreira Reference Haas and Ferreira2015, Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro, Reino, Schindler, Strubbe, Vall-llosera, Araújo, Capinha, Carrete, Mazzoni, Monteiro and Moreira2019). This often results in overexploitation of wildlife leading to the loss of biodiversity and disruption of ecosystem processes (Broad et al. Reference Broad, Mulliken and Rose2003, Wasser et al. Reference Wasser, Poole, Lee, Lindsay, Dobson, Hart, Douglas-Hamilton, Wittemyer, Granli, Morgan and Gunn2010).

South-east Asia has been identified as a hotspot for illicit wildlife trade (TRAFFIC 2008, Nijman Reference Nijman2010). Vast numbers of wildlife are traded in animal markets in the region, many of which are trapped illegally (Nash Reference Nash1993, Chng et al. Reference Chng, Eaton and Shepherd2018). Amongst bird species, parrots, and songbirds (passerines) are commonly owned pets both globally and in the region, and demand for these species has been linked to the extirpation of wild populations of many species within these groups (Eaton et al. Reference Eaton, Shepherd, Rheindt, Harris, van Balen, Wilcove and Collar2015, Lee et al. Reference Lee, Chng and Eaton2016, Olah et al. Reference Olah, Butchart, Symes, Guzmán, Cunningham, Brightsmith and Heinsohn2016).

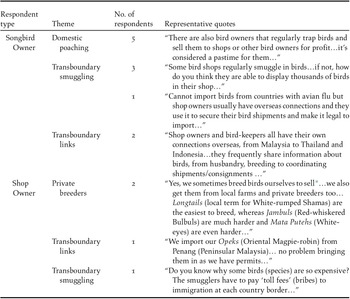

The practice of keeping songbirds is a highly popular pastime that is deeply rooted in local cultures within South-east Asia (Jepson and Ladle Reference Jepson and Ladle2005, Kirichot et al. Reference Kirichot, Untaya and Singyabuth2015, Iskandar et al. Reference Iskandar, Iskandar and Partasasmita2019; Fig. 1b), as well as other Asian countries like China and India (Layton Reference Layton1991). This practice is one of the main contributors to the cage-bird trade in the region (Nash Reference Nash1993, Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Collar, Lees, Moss, Yuda and Marsden2020a). Moreover, bird singing competitions are popular in many South-east Asian countries, further exacerbating the demand for songbirds (Jepson and Ladle Reference Jepson and Ladle2009). The unprecedented levels of overexploitation have already led to precipitous declines of songbird species in the wild. The Straw-headed Bulbul Pycnonotus zeylanicus for instance, was uplisted from ‘Vulnerable’ to ‘Critically Endangered’ on the IUCN Red List within a short span of two years, following the collapse of wild populations in Thailand and Indonesia (BirdLife International 2018, Chiok et al. Reference Chiok, Miller, Pang, Eaton, Rao and Rheindt2019).

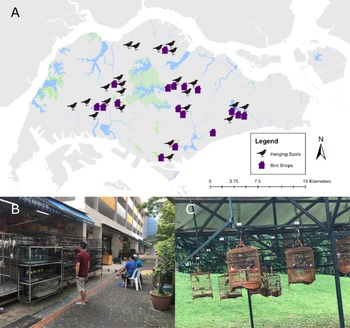

Figure 1. (a) Map indicating locations of bird shops and hanging spots found across Singapore. Symbols give an approximate location of the site and do not give the absolute number as some locations have multiple shops in close proximity. (b) Example of a bird shop in Singapore. (c) Example of a bird cage hanging spot in Singapore.

Highly urbanised Singapore, where the keeping of pet birds (songbirds in particular) is believed to have started in the 1950s and remains prevalent, is no exception (Layton Reference Layton1991, Lai Reference Lai2010, Ng Reference Ng2018a; Fig. 1b). There exists a highly active pet bird industry in Singapore, previously underestimated (Aloysius et al. Reference Aloysius, Yong, Lee and Jain2019), and comparable to markets in Indonesian cities. At least 14,000 birds were recorded in 28 local bird shops during a market survey conducted in 2015 (Eaton et al. Reference Eaton, Leupen and Krishnasamy2017). While studies have highlighted Singapore’s role as a key transit hub (Shepherd et al. Reference Shepherd, Stengel and Nijman2012, Poole and Shepherd Reference Poole and Shepherd2016, UNODC 2016, Aloysius et al. Reference Aloysius, Yong, Lee and Jain2019) and its fairly active domestic bird market (Eaton et al. Reference Eaton, Leupen and Krishnasamy2017), research that focuses on the consumers is sparse.

Given Singapore’s integral role in the international wild bird trade (TRAFFIC 2019), a robust understanding of the socio-economic and demographic context and the dynamics of the songbird trade are critical in implementing effective demand reduction strategies and promoting sustainable trade (Burivalova et al. Reference Burivalova, Lee, Hua, Lee, Prawiradilaga and Wilcove2017, Nuno et al. Reference Nuno, Blumenthal, Austin, Bothwell, Ebanks‐Petrie, Godley and Broderick2018, Veríssimo and Wan Reference Veríssimo and Wan2019, Miller et al. Reference Miller, Gary, Juhardiansyah, Muflihati and Adirahmanta2019). In particular, we focus on the domestic stakeholders that shape and influence the songbird community in Singapore—including the preferences, motivations, and local biodiversity knowledge of individual owners (Wasser and Jiao Reference Wasser and Jiao2010, Theng et al. Reference Theng, Glikman and Milner-Gulland2018, Doughty et al. Reference Doughty, Veríssimo, Tan, Lee, Carrasco, Oliver and Milner-Gulland2019, Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Collar, Lees, Moss, Yuda and Marsden2020b), as well as their social links and interactions within the songbird community. We thus undertook this consumer-centric study to characterise the drivers of demand for songbirds in Singapore and the key stakeholders involved. To do this, we (i) investigate the socio-economic factors and demographics of songbird owners in Singapore as well as their motivations towards owning songbirds, (ii) assess conservation awareness via their knowledge levels with regards to local fauna and nature, and lastly, (iii) map out the domestic songbird trade network in Singapore and highlight important links within the network that warrant conservation attention. The insights generated from this study will help illuminate the status of songbird trade in Singapore. It will also inform the development of songbird conservation strategies in Singapore, such as policy revisions and demand reduction programmes, and serve as baseline information for future studies to build upon from.

Methods

Study design

We first identified and visited a total of 30 out of 42 licensed bird shops and 19 cage-bird hanging spots (hereafter hanging spots) across Singapore. Across these sites, we subsequently conducted semi-structured surveys with 114 songbird owners between November 2018 and February 2019. This comprised 97 (85%) in-person and 17 (15%) digital responses.

Identifying bird shops and hanging spots

We visited bird shops and their surroundings to ascertain possible locations where the survey could be conducted (Figs. 1a, 1b). Hanging spots were identified by scouting the vicinity of bird shops, through word-of-mouth and informal conversations with songbird owners. These spots possess infrastructure that allow for the hanging of multiple bird cages and could either be set up adjacent to bird shops by the owners, or standalone structures erected by private individuals or the local government (Fig. 1c). Each site (bird shop or hanging spot) was visited at least once and sites that were deemed to have higher human traffic were visited multiple times to increase the chances of obtaining responses. We recorded the location and dates of bird singing competitions that were displayed on flyers at the sites (Fig. S1 in the online supplementary material) or online platforms such as Facebook. This enabled us to conduct opportunistic sampling during these events, where a high number of songbird owners were present.

Survey formulation and administration

Bird shops and hanging spots where the survey was conducted were selected non-randomly to maximise the number of respondents. However, within each shop and hanging spot, respondents were selected via convenience sampling. Interviewers (WXC and RL) were present on-site to facilitate the recording of responses and to answer any queries posed by respondents. To reduce the impact of self-selection bias, potential respondents were asked if they were willing to participate in a survey about bird ownership in Singapore, without describing the topic or objective of the project. Additional responses were gathered via respondent-driven sampling (Newing Reference Newing2011) and through continued site visits. Digital responses were collected using Google forms by posting announcements on online platforms and circulated in Telegram/WhatsApp groups via snowball sampling. The digital and print formats of the survey were identical. The data were anonymised, and no personal identifiers were collected. Overall, the face-to-face approach was favoured in this study as it had greater response rates as compared to online surveys and is usually more representative of the target population (Groves et al. Reference Groves, Fowler, Couper, Lepkowski, Singer and Tourangeau2009).

The survey comprised of three sections and a total of 23 questions (Appendix S1 in the online supplementary material). The sections were structured such that songbird owners were surveyed on (i) their reasons, motivations, preferences for bird-keeping and species kept; (ii) their level of conservation awareness via their knowledge of nature in Singapore, such as the native status of species (mostly birds) commonly found in the country (as with Jain et al. Reference Jain, Aloysius, Lim, Plowden, Yong, Lee and Phelps2021) and overseas (such as hummingbirds); and (iii) respondent demographic profiles. The survey was conducted in accordance with BirdLife International and British Sociological Association guidelines.

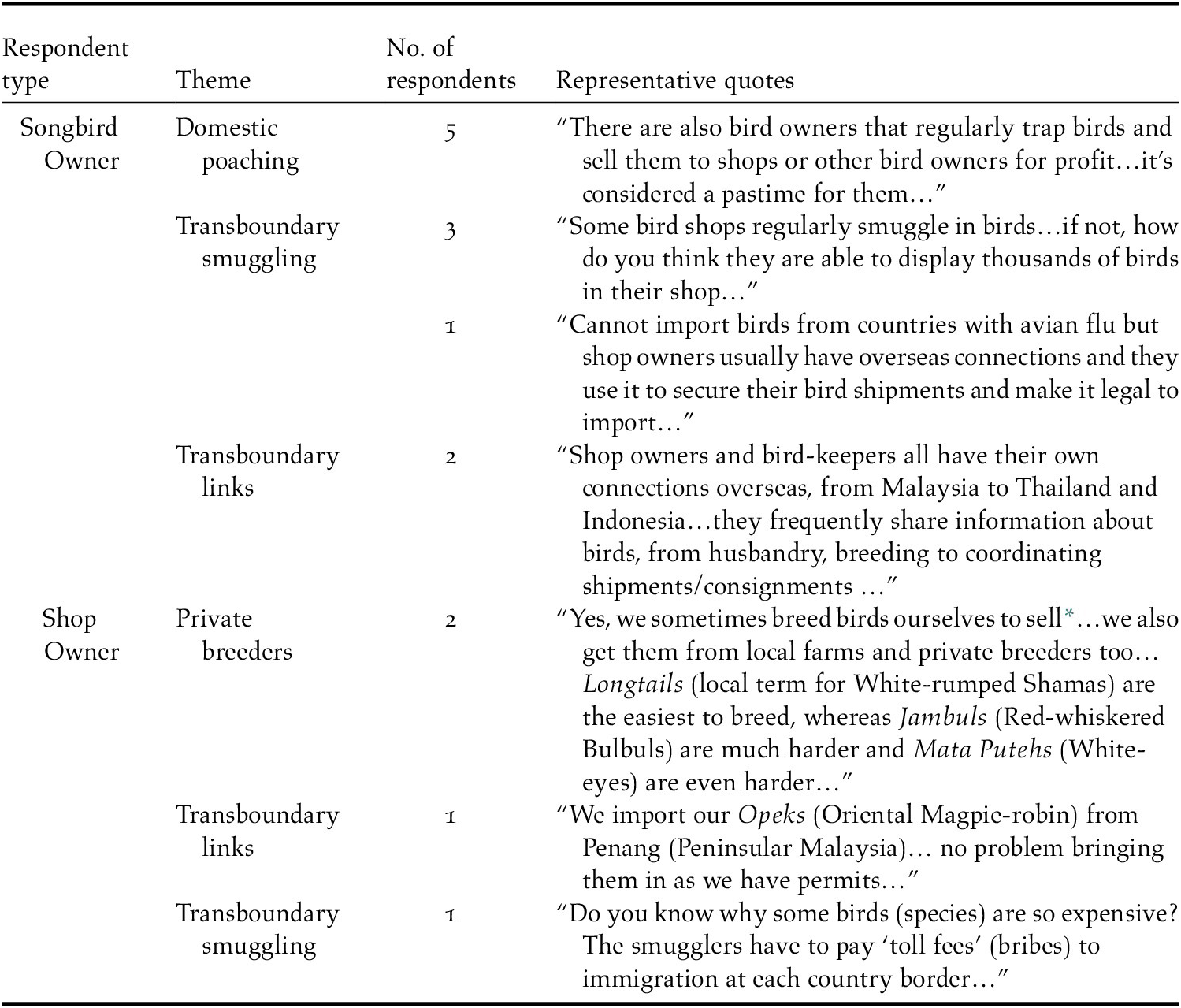

Beyond answering the questions in the survey, some respondents also shared their opinions and anecdotal information on the role of bird shops and hanging spots about potentially illicit activities around songbird trade in Singapore including cross-border trade (Poole and Shepherd Reference Poole and Shepherd2016) and domestic poaching (Quek Reference Quek2018, Low Reference Low2020). These were documented to the extent possible (Corbin and Strauss Reference Corbin and Strauss2008) and are presented in the results.

Data analyses

All but two questions from the survey responses were analysed with descriptive statistics, but only selected results are discussed and presented in the main text. True/False questions in the second section of the survey comprised of two main questions (see questions 13 and 14 in Appendix S1) that were evaluated using a point-scoring system. A single point was given for each question answered correctly, where 0 = “Zero questions answered correctly”, 1 = “One question answered correctly” and so on. As some questions were skipped by respondents, the total responses for each question are indicated where relevant. Two questions that were about buying new songbirds (see questions 10 and 12 in Appendix S1) were omitted from the analysis and not discussed here, due to the miscomprehension of the questions by respondents. Responses in the ‘Others’ section for relevant questions were post-processed and allocated specific categories (e.g. hobby, recreation and pastime were treated as ‘pastime’ for Q5, and similarly for Q4).

Limitations

We acknowledge that our sample may be biased towards respondents who possess an interest in bird singing competitions and regularly partake in it because the majority of our surveys were administered near bird shops and hanging spots. However, this may well be representative of the songbird community as bird-keeping is known to be a community-focused hobby, where owners tend to gather and socialise at sites that have infrastructure to hang bird cages (Fig. 1c). These structures tend to be multi-purpose and can sometimes be utilised as competition sites (Layton Reference Layton1991, Kirichot et al. Reference Kirichot, Untaya and Singyabuth2015). Additionally, some respondents may not be forthcoming or may have exhibited social desirability bias (i.e. methodically alter a response in the way that respondents perceive to be desirable by the administrator; Nancarrow and Brace Reference Nancarrow and Brace2000, Choi and Pak Reference Choi and Pak2005, Smith Reference Smith2007) because we asked sensitive questions about their preference for the source of birds (captive-bred or wild-caught). Taken together, these limitations imply that insights presented here may represent the best-case scenario about willingness towards songbird conservation across songbird owners in Singapore.

Results

Respondent demographics

Of the 114 respondents, 63% were songbird owners with more than 15 years of experience in bird-keeping. Approximately 6% had 11–15 years of experience, whilst the remaining 30% had 10 years or less of bird-keeping experience (Fig. S2). Respondents were predominantly male (95%) and most were of Chinese ethnicity (67%), followed by Malays (18%) and Indians (14%). Most were of age 40 years and above (77%), with a small percentage (9%) aged 30 and below (Fig. S3). The median age ranged from 51 to 60 years. Of the 89 respondents who reported their salary, 27% had monthly income levels of S$2,500 to S$4,999 which was somewhat above the national median (Singapore’s median income in 2018 was reported to be S$2,792; Singapore Department of Statistics 2019), whilst 33% had monthly income levels above S$5,000. The remaining 40% of respondents had income levels below the median.

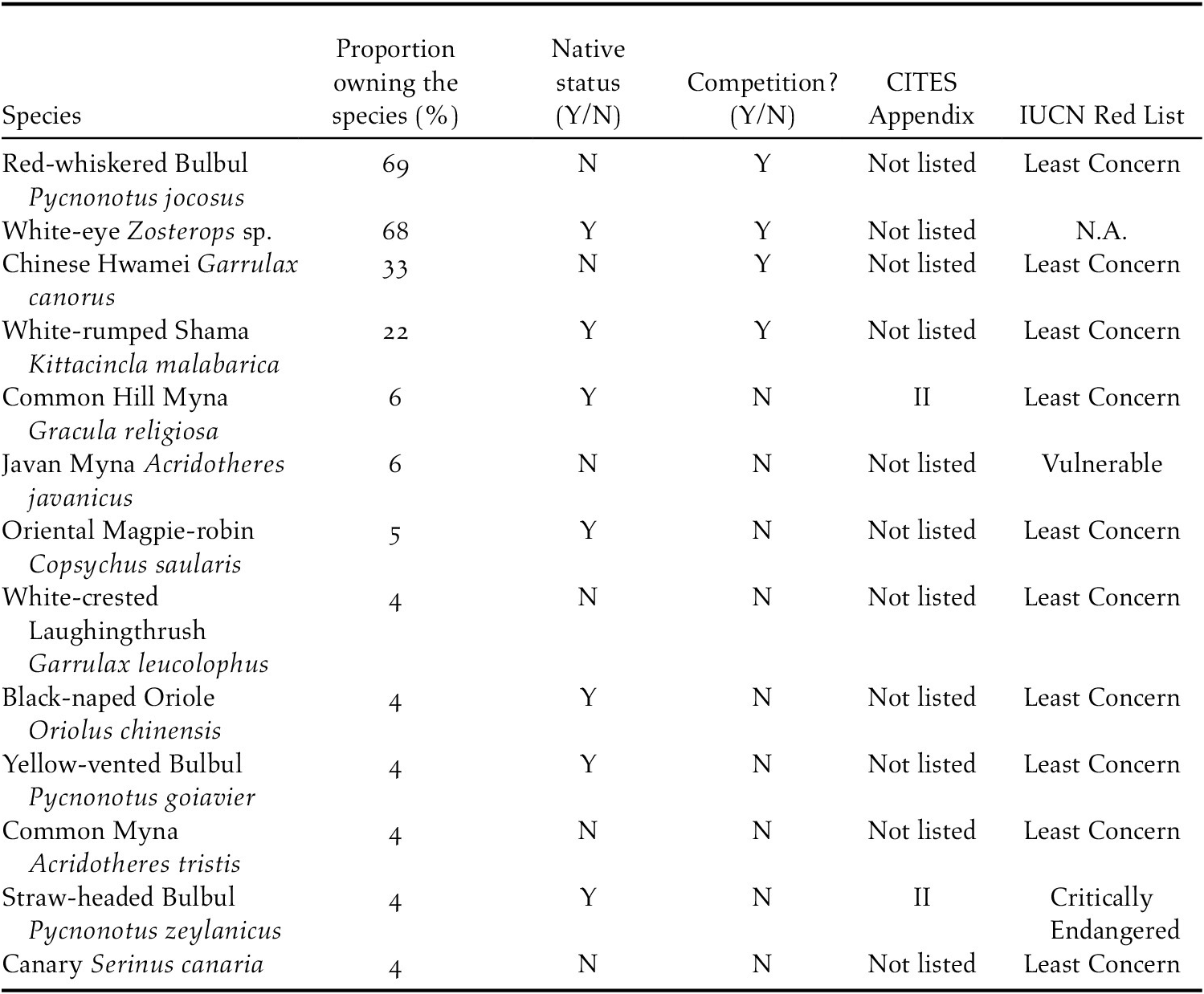

Popular species among songbird owners and their source

We found that the respondents (n = 114) reportedly kept at least 12 species of songbirds collectively. Over half of the species (58%, seven out of 12) kept by respondents are native to Singapore (Table 1). The Red-whiskered Bulbul Pycnonotus jocosus and White-eye Zosterops sp. (see Lim et al. Reference Lim, Sadanandan, Dingle, Leung, Prawiradilaga, Irham, Ashari, Lee and Rheindt2019 for taxonomy) were the two most popular species, with 69% and 68% of respondents owning these species respectively (Table 1). This was followed by the Chinese Hwamei Garrulax canorus and White-rumped Shama Kittacincla malabarica that were owned by 33% and 22% of respondents respectively.

Table 1. Table of songbird species kept by respondents, their native status in Singapore, whether songbird competitions are held for them, and their respective status in CITES and IUCN. Species are listed in descending order of percentage proportion reportedly owned by respondents (n = 114).

Amongst the top four songbird species owned, all are seen in local songbird competitions. Of these, the White-rumped Shama and White-eye are native to Singapore (Table 1). However, these two species are also regularly imported by bird shops in Singapore (Ng et al. Reference Ng, Garg, Low, Chattopadhyay, Oh, Lee and Rheindt2017, WXC and RL pers. obs.), and are usually from overseas countries. Of the 12 species reportedly kept by respondents, two were globally threatened on the IUCN Red List (IUCN 2019)—the ‘Critically Endangered’ Straw-headed Bulbul Pycnonotus zeylanicus, and ‘Vulnerable’ Javan Myna Acridotheres javanicus. Only the Straw-headed Bulbul and Common Hill Myna Gracula religiosa are listed on Appendix II of CITES (Table 1).

We encountered 10 respondents who openly shared their past accounts of local bird trapping and cross-border smuggling. Five remarked that several of their peers regularly set up bird traps across Singapore and sold the trapped birds. Three respondents remarked that certain bird shops regularly bring in shipments of wild-caught birds of unknown legality (Table 2). However, these anecdotal personal accounts will need to be investigated further for accuracy.

Table 2. Relevant illustrative quotes extracted from respondents (n = 10).

* This has also been observed by the authors (WXC and RL) while visiting pet bird shops during the study.

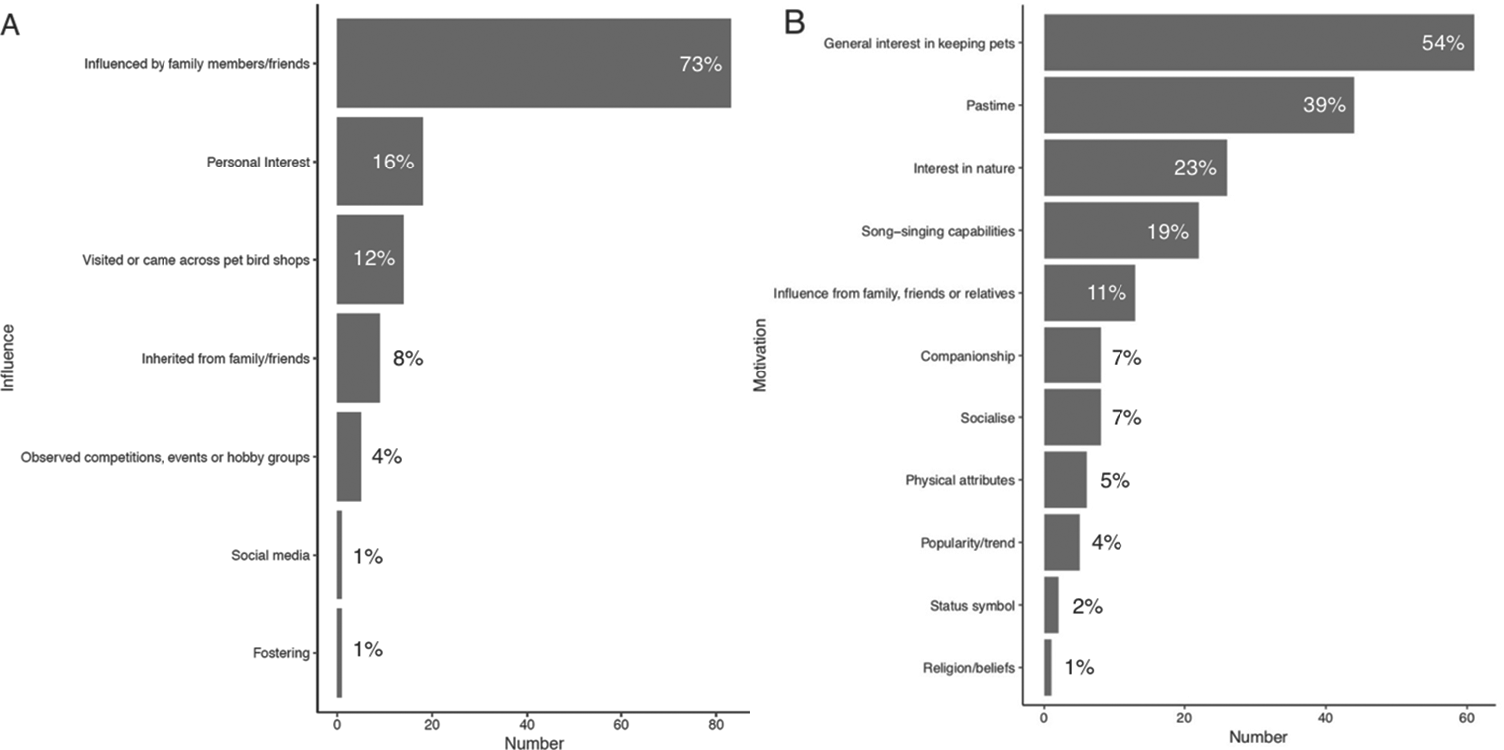

Motivations and preferences

When asked to select the top three factors that influenced respondents to take up bird-keeping (n = 114), “friends and family members” was found to be the most influential factor (73%) (Fig. 2a), however, it did not influence their decision to continue the hobby. Only one respondent selected status symbol as a motivation to bird-keeping in Singapore (Fig. 2b). Respondents who chose “personal interest” (16%) cited heritage and tradition as their reason for wanting to keep birds. Only a single respondent chose “social media” as the factor that influenced the person to take up bird-keeping. When asked what were the top motivational factors keeping them in the hobby (n = 114), over half of the respondents (54%) chose “general interest in keeping pets” as their main motivation towards bird-keeping (Fig. 2b). This was followed by “pastime” (39%, from ‘Others’) and “interest in nature” (23%). The same group of respondents also cited their childhood exposure to nature as the factor that sparked their interest in bird-keeping. However, over half of our respondents (56%) only visited natural spaces once every few months (Fig. S4).

Figure 2. (a) Factors influencing respondents’ entry into bird-keeping. (b) respondents’ motivations toward owning songbirds after getting into the hobby (n =114).

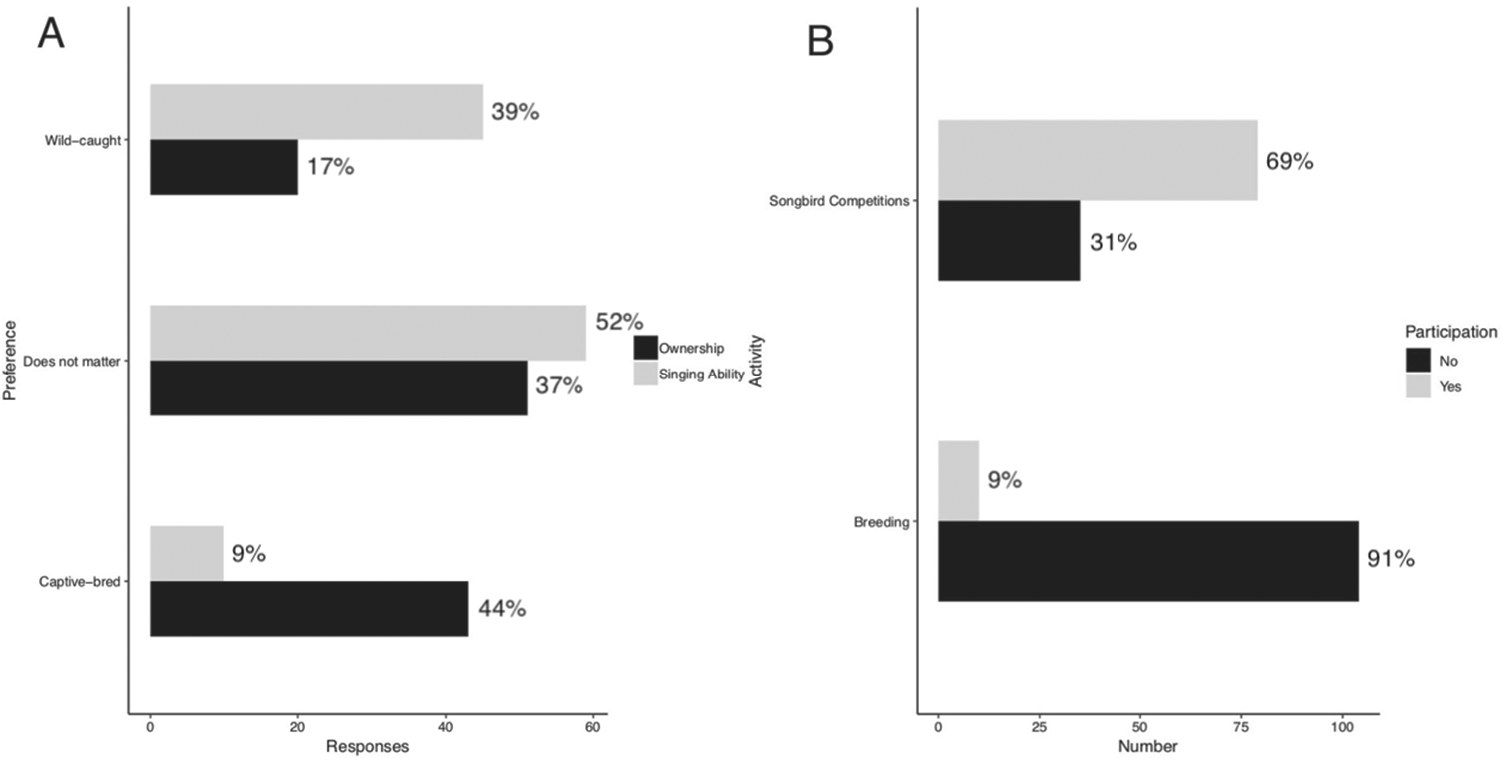

With regard to the source of birds (captive-bred versus wild-caught; n = 114), 45% of respondents said it was inconsequential to them, while 38% preferred captive-bred birds (Fig. 3a). Only 17% preferred wild-caught birds. When songbird owners were asked whether captive-bred or wild-caught birds had better singing capabilities, more than half (52%) felt that there was no difference (Fig. 3a). However, 39% of respondents deemed wild-caught individuals to have better singing capabilities, with only 9% indicating captive-bred individuals to have better singing capabilities.

Figure 3. (a) Respondents’ preference towards bird-keeping in Singapore (n = 114). ‘Ownership’ refers to the respondents’ preference to keep wild-caught or captive-bred individuals, if given the choice. ‘Singing Ability’ refers to the respondents’ perceived quality of song produced by wild-caught or captive-bred birds. An option ‘Does not matter’ is provided for songbird owners that do not have any preference towards the background of an individual. (b) Number of respondents participating in songbird competitions or are breeding songbirds. When questioned further, many of those involved in breeding mentioned that they breed the White-rumped Shama.

When asked whether respondents bred songbirds or took part in bird singing competitions (Fig. 3b), an overwhelming majority said that they did not breed songbirds (91%, or 104 out of 114 respondents), whereas 69% took part in competitions. When questioned further, respondents that partook in breeding claimed that it was only feasible for White-rumped Shama and that local attempts at breeding the Red-whiskered Bulbul and White-eye have not been as successful as the White-rumped Shama (Table 2).

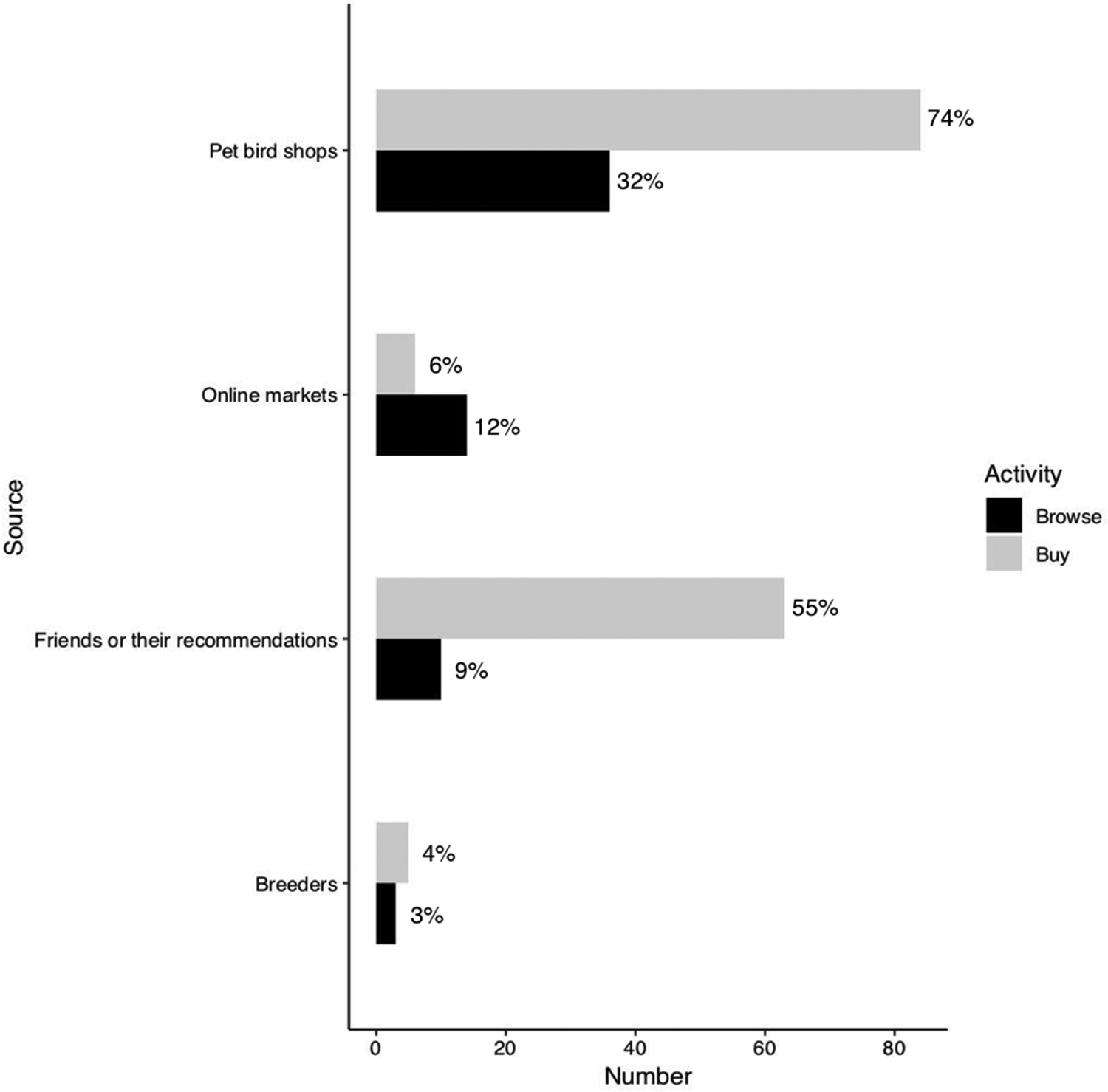

Physical bird shops were still preferred by respondents (n = 114), who were more likely to browse (32%) and purchase (74%) songbirds through the shops, showing the continued importance of brick-and-mortar establishments (Fig. 4). Not surprisingly, at least five bird shops were observed to erect infrastructure for patrons to hang their bird cages (Fig. S5) and even host bird singing competitions. Hanging spots situated near bird shops were observed to be more likely to be frequented by owners as compared to standalone sites. Coffee shops were also observed as gathering sites for songbird owners where all matters of bird-keeping and sale of birds were discussed (WXC and RL pers. obs.). Our observations, therefore, echo those of Lai (Reference Lai2010), who mentioned that it is “common for bird owners to bring their pets daily to the kopitiam (colloquial term for coffeeshop)…cages hung on tall stands outside…birds stimulate each other to sing while their owners drink, chat and compare notes on their hobby”. Other sources of purchasing songbirds were through their friends (55%) in the form of gifts, exchanges, barter trade, private sales or via word-of-mouth exchange amongst hobbyists (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Sources from which respondents bought or obtained songbirds from (n = 114). ‘Online markets’ represents marketplaces on social media platforms like Facebook, as well as online listings on Gumtree Singapore (www.gumtree.sg). ‘Friends or their recommendations’ refers to the exchange or sale of songbirds that an owner does not want to keep any longer (sometimes referred to as adoptions). Reasons for giving up songbirds vary from lacklustre performances at competitions, insufficient housing spaces, to purchases of new birds as replacements.

More than three-quarters (82%) of respondents indicated that they were not part of any hobbyist groups, with only 13% involved in online groups (Fig. S6) and with similarly small proportions that buy (6%) and/or browse (12%) from online marketplaces (Fig. 4).

Conservation and biodiversity awareness

Nearly two-thirds (65%) of respondents obtained a passing score of 8 out of 15 (53%) or more regarding their knowledge about nature in Singapore (Fig. S7). However, a slightly lower proportion (59%) were able to identify 8 out of 15 or more native species. The top species that had that their native status identified correctly by respondents was the Yellow-vented Bulbul (86%). A large proportion (79%) incorrectly believed that the Red-whiskered Bulbul was native to Singapore, and 59% incorrectly indicated the White-crested Laughingthrush to be a native species—perhaps because both species have established populations in Singapore (Sodhi and Sharp Reference Sodhi and Sharp2006, Wong Reference Wong2014). Nearly half (47%) failed to classify the native status of the White-rumped Shama (native to Singapore) correctly. The majority of respondents (88%) incorrectly thought that hummingbirds where native to Singapore. They would likely have mistaken the local sunbird species as hummingbirds.

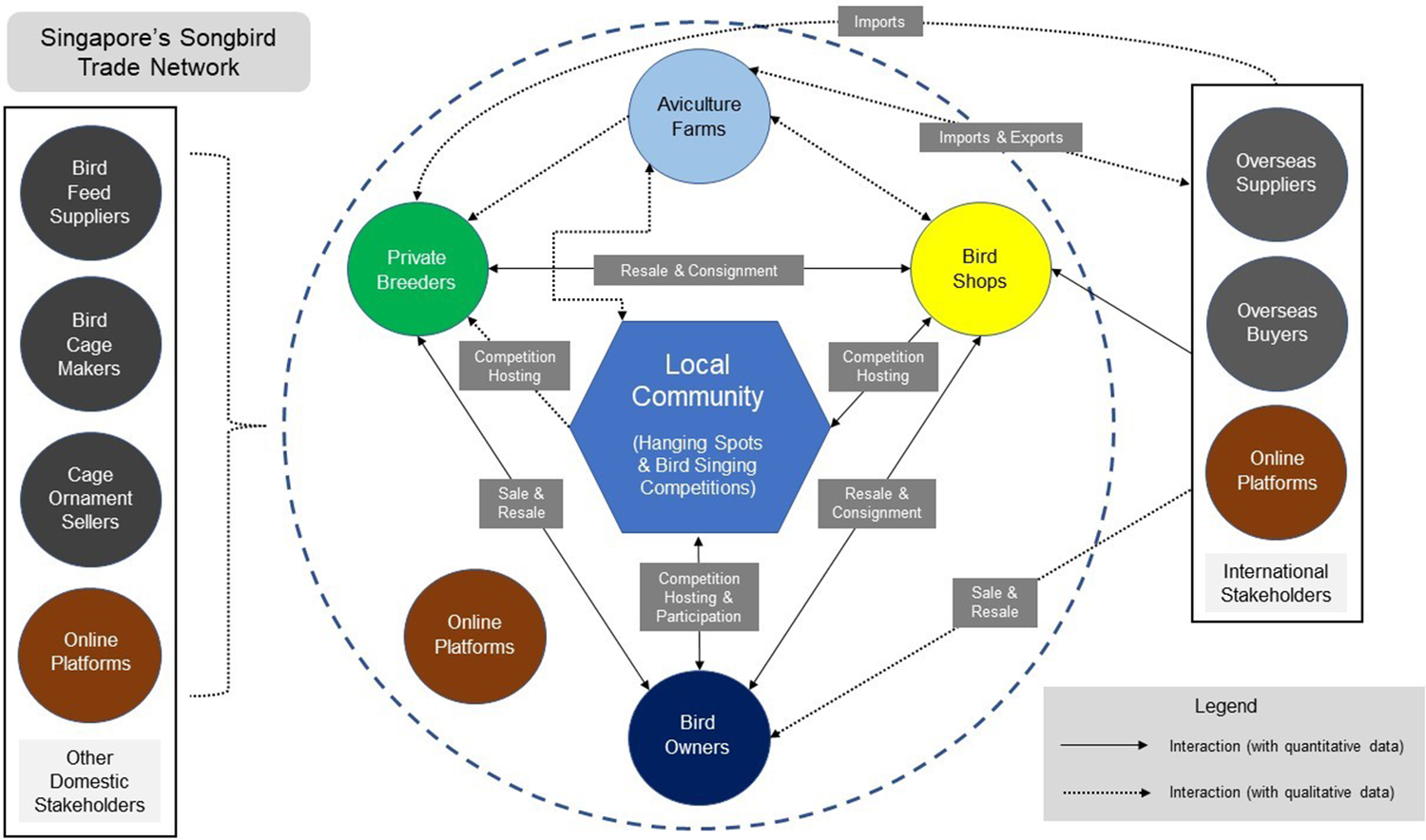

Songbird trade network and community-based linkages

With information gathered from multiple sources – semi-structured surveys, respondent accounts (Table 2) and references to other related studies (Poole and Shepherd Reference Poole and Shepherd2016, Chiok and Chng Reference Chiok and Chng2021, Jain et al. Reference Jain, Aloysius, Lim, Plowden, Yong, Lee and Phelps2021), we were able to qualitatively map out the songbird trade network in Singapore (Fig. 5). It highlighted the importance of the local community through hanging spots and bird singing competitions as the mainstay that drives and fuels songbird keeping and trade. Indeed, ‘community’ was a recurring keyword brought up by over half of the respondents during our informal conversations while conducting the surveys and was described as the main influential factor that motivated them to start bird-keeping and/or continue their hobby. Moreover, several bird shops were observed to form collaborations and/or business partnerships with local and overseas bird ownership-related suppliers or private breeders to market their businesses (Chiok and Chng Reference Chiok and Chng2021, Jain et al. Reference Jain, Aloysius, Lim, Plowden, Yong, Lee and Phelps2021). Bird shops are also known to consign birds from private songbird owners, which includes home breeders as well as owners who may lack the know how to directly sell their birds (e.g. elderly people who are not tech-savvy). These linkages exhibit a high level of interconnectivity between commercial and private (hobbyists) entities within Singapore’s songbird community.

Figure 5. Overview of Singapore’s songbird trade network, depicting key domestic and international stakeholders involved the trade. Arrows indicate direction of trade flow between stakeholders. Online platforms have been found to be pervasive across the entire trade network, and as such, no arrows were associated due to its ubiquity.

Discussion

This study provides some of the first insights on songbird ownership in Singapore, by characterising the inherent social drivers of demand (motivations and preferences), demography and knowledge levels of owners, species kept, and the mapping of the interconnectedness of Singapore’s songbird trade network. We show that the respondents surveyed here were experienced owners, majority of which were male, of Chinese ethnicity and aged 40 or older. These owners were motivated to pick up bird-keeping largely due to influence from their fellow family and friends, with their interest in pet keeping, nature and yearning for a pastime driving their continued pursuit in this hobby. However, owners did not seem to have a distinct preference with regard to their source of birds, despite having the notion that wild-caught birds have a better song repertoire. In the following paragraphs, we discuss the importance of socio-cultural factors within the songbird community in Singapore, the biodiversity awareness of owners and the implications for conservation.

Drivers of demand and influence of social elements

Our results suggest that songbird ownership in Singapore exists within a complex social network (Fig. 5), with the community centred around hanging spots being a highly influential driver, starting with friends and family members who influenced survey respondents to take up bird-keeping. An amalgamation of physical (hanging spots), virtual (online marketplaces), commercial (bird shops) and socio-cultural factors are interwoven within the community, driving the demand for songbird ownership (Fig. 5). Bird shops, cagebird hanging spots and other informal gathering spaces (e.g. coffeeshops) serve as important social spaces to motivate, connect and bond the songbird community about their pet birds (Fig. 5; Layton Reference Layton1991, Lai Reference Lai2010), more so for the older individuals that make up the majority of songbird users in Singapore, and can be expected to bond at physical gatherings and events. In contrast, parrot-keeping in Singapore attracts more youth perhaps because it is portrayed as a ‘fashionable hobby’ by the media (Jain et al. Reference Jain, Aloysius, Lim, Plowden, Yong, Lee and Phelps2021). Equally, the average age of songbird owners in Indonesia is also somewhat lower at approximately 40 years (Burivalova et al. Reference Burivalova, Lee, Hua, Lee, Prawiradilaga and Wilcove2017), implying that songbird keeping in Singapore may not be as fashionable anymore.

Our findings that the majority of songbird owners in Singapore were not part of any hobbyist groups, with only 13% involved in online groups, contrasts with local parrot-keeping where more than half of owners are estimated to be part of online hobbyist groups and arguably younger than songbird owners (Jain et al. Reference Jain, Aloysius, Lim, Plowden, Yong, Lee and Phelps2021). Interestingly, no online songbird competitions have been observed in Singapore since April 2020 during COVID-19 lockdowns and restrictions on physical gatherings despite that such online competitions have emerged in Indonesia (Armstrong and Chng Reference Armstrong and Chng2020). This may be because the songbird community in Singapore is typically older and may not be so technologically savvy, placing further emphasis on the importance of physical gatherings and community interaction (Fig. 5).

In general, online media are known to be highly popular with various types of wildlife trade in Singapore (Mahmud Reference Mahmud2017, Sung and Fong Reference Sung and Fong2018, Chiok and Chng Reference Chiok and Chng2021, Jain et al. Reference Jain, Aloysius, Lim, Plowden, Yong, Lee and Phelps2021; Fig. 5), and in the region (Iqbal Reference Iqbal2015, Krishnasamy and Stoner Reference Krishnasamy and Stoner2016, Indenbaum Reference Indenbaum2018, Martin et al. Reference Martin, Senni and D’Cruze2018), where online markets offer enhanced connectedness and anonymity to users, driving the demand for illegal trade (Grabosky Reference Grabosky2013, Lavorgna Reference Lavorgna2014, Harrison et al. Reference Harrison, Roberts and Hernandez‐Castro2016). The importance to songbird keeping in Singapore warrants further investigation.

Role of songbird competitions and the importance of communities

Bird-singing competitions appear to be an integral part of Singapore’s songbird community (Ng Reference Ng2018a; Fig. 5) with most songbird owners participating in them. These competitions influence which songbird species are popular as pets in Singapore. Surprisingly, competition participation rates in Singapore appear to be even higher than in Indonesia (26% in Java, 13% of Indonesia as a whole; see Jepson et al. Reference Jepson, Ladle and Sujatnika2011, Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Collar, Lees, Moss, Yuda and Marsden2020a). Because the entry costs to songbird competitions in Singapore and the associated prizes are low (typically ranging from grocery vouchers to televisions and radio sets; Fig. S1), the competitions appear to be more of a social, friendly, and structured platform for songbird owners and their birds to interact, compared to the more serious and competitive songbird competitions elsewhere in the region. For example, bird singing competition prizes in Indonesia and Thailand tend to be big where winners can walk home with luxurious cash prizes, a new car or house (Kirichot et al. Reference Kirichot, Untaya and Singyabuth2015).

In Singapore, songbird ownership does not appear to be a status symbol, perhaps because of the low monetary value attached to bird-singing competitions, which can be a major avenue for publicly displaying one’s collection of birds. Conversely, owning birds is considered a status symbol in Indonesia, due to cultural norms and traditions associated with bird-keeping (Jepson and Ladle Reference Jepson and Ladle2005, Jepson et al. Reference Jepson, Ladle and Sujatnika2011) and particularly among competition contestants and breeders in Indonesia who tend to own more valuable species (Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Collar, Lees, Moss, Yuda and Marsden2020b). In contrast, parrot ownership is deemed to be a form of status symbol for owners in Singapore as it is being portrayed as a fashionable hobby (Aloysius et al. Reference Aloysius, Yong, Lee and Jain2019, Jain et al. Reference Jain, Aloysius, Lim, Plowden, Yong, Lee and Phelps2021). This suggests that multiple factors such as culture, fashion and monetary rewards can influence community response towards a group of species (parrots or songbirds) for them to be regarded as status symbols.

Our study methodology and sample size did not allow us to make distinctions between preferences of songbird ownership between hobbyists and competition contestants in Singapore. Our surveys may also have underrepresented collectors and purveyors of exotic species who typically do not enter their birds into competitions. Some songbird owners who declined to partake in our survey revealed that they do not join bird song competitions and preferred to cultivate their hobby at home or at bird hanging spots (Fig. S8, Fig. 5). This may also explain the discrepancy between a low diversity of songbirds kept by respondents in our study when compared with past market surveys (Lee Reference Lee2006, Eaton et al. Reference Eaton, Leupen and Krishnasamy2017).

Indifference towards cage-bird provenance

Intriguingly, songbird owners in our study reported indifference towards the source of the birds (wild-caught vs. captive-bred) and between the singing capabilities of wild-caught or captive-bred birds (Fig. 3). In fact, fewer songbird owners preferred wild-caught songbirds, citing the ease of training captive individuals as one of their reasons. Additionally, some respondents remarked that the training techniques employed matter more than the source of the bird and that captive-bred individuals are usually tamer and easier to train. The preferences of songbird owners in Singapore are similar to those in Indonesia, who rank convenience and availability above bird origin or song quality (Burivalova et al. Reference Burivalova, Lee, Hua, Lee, Prawiradilaga and Wilcove2017, Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Collar, Lees, Moss, Yuda and Marsden2020b). This insight can be particularly useful for conservation planning, as owners surveyed here appear to have a high propensity to purchase captive-bred birds that can be sourced legally and sustainably.

Conservation implications and future research

Our research has provided valuable information on songbird ownership and the interconnectedness of the songbird trade network in Singapore. This could be vital in informing conservation interventions and particularly demand reduction programs for wild-caught songbirds in Singapore and other cities in the region. Our research can also contribute to the IUCN SSC Asian Songbird Trade Specialist Group (ASTSG), particularly in the area of community engagement by providing primary data on consumer demands, motivations and preferences towards bird-keeping which is currently poorly understood outside of Indonesia.

The differences in motivation and preferences observed in songbird owners in Singapore, when compared to studies in Indonesia, underscores the need to take into consideration local factors that influence the motivations towards bird-keeping.

While consumer behaviour patterns are increasingly being recognised as significant drivers of demand, most policies concerning unsustainable wildlife trade and conservation have yet to incorporate social behavioural science to understand consumers and develop appropriate demand reduction approaches (Challender et al. Reference Challender, Harrop and MacMillan2015, Wallen and Daut Reference Wallen and Daut2018). Evidence-based conservation interventions tailored towards specific demographics (e.g. older Chinese men who are the dominant songbird owners) and delivered through bird singing competition associations/clubs and hanging spots—rather than a general awareness-raising campaign—could likely elicit positive outcomes.

We can also draw upon lessons learned from previous successful behaviour change campaigns, such as those to reduce Singapore shark’s fin consumption (WWF 2016), and ivory trade (Ng Reference Ng2018b) in which biodiversity awareness-raising campaigns have been observed to have positive impacts on raising awareness of the public (Chua et al. Reference Chua, Tan and Carrasco2021).

Such campaigns may be particularly useful for songbirds because the majority of respondents in Singapore appear to have no preference towards the source of songbirds or prefer captive-bred songbirds and to some extent, are knowledgeable about local biodiversity. Greater knowledge about biodiversity conservation seems to drive positive perceptions towards unsustainable forms of wildlife trade (Ivy et al. Reference Ivy, Road, Lee and Chuan1998, Shafie et al. Reference Shafie, Sah, Mutalib and Fadzly2017, Jain et al. Reference Jain, Aloysius, Lim, Plowden, Yong, Lee and Phelps2021). Childhood exposure to nature (Ngo et al. Reference Ngo, Hosaka and Numata2019) and the access and frequency of visits to natural spaces are known to shape and affect one’s perceptions towards conservation (Khew et al. Reference Khew, Yokohari and Tanaka2014, Hwang et al. Reference Hwang, Yue, Ling and Tan2019).

Further research on the songbird community in Singapore with a larger sample size is warranted to understand owners’ willingness to buy sustainably sourced birds. The underlying factors that shape and affect songbird owners’ perceptions towards nature conservation could be tackled as well (Chiu et al. Reference Chiu, Chan and Marafa2016, Richards et al. Reference Richards, Fung, Leong, Sachidhanandam, Drillet and Edwards2020). The quantification of socioeconomic factors of bird shop owners and songbird competition organisers in Singapore (see Miller et al. Reference Miller, Gary, Juhardiansyah, Muflihati and Adirahmanta2019) would also allow for an understanding of their willingness towards switching enterprises and moving towards alternative sustainable livelihoods.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270921000393.

Acknowledgements

We thank Madhu Rao for her guidance during the inception of the study, Janice Lee and Ding Li Yong for their invaluable feedback throughout the study, David Tan, Margie Hall and Ngo Kang Min for reviewing earlier versions of the manuscript. This research was funded by the Mandai Nature Fund (formerly Wildlife Reserves Singapore).