Abstract

We develop and test an equilibrium model of party structure to account for the large and ever-changing number of political parties that contest Indian state elections. The analysis finds that the number of parties increases with the voting density of state constituencies, the heterogeneity of the state’s electorate, state per capita income and literacy levels, falls with average age while responding to a set of constitutional and legislative rules designed to affect party and electoral performance. The model is also applied to entry and exit, allowing the empirics to highlight those factors that affect party turnover rather than aggregate party numbers. The model explains better the number of parties than ENP, the effective (vote share weighted) number of parties, implying that the variability in the fringe of smaller parties has not substantially affected the vote shares received by the larger more established parties. Affirmative action, primarily in the form of increases in the proportion of seats reserved for members of special castes is associated with a reduction in both party numbers and ENP consistent with speeding the integration of scheduled castes into broader based political parties.

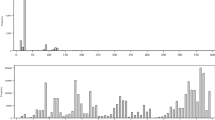

Source: The Election Commission of India (ECI) at https://eci.gov.in/statistical-report/statistical-reports/ by election year and with ENP calculations by the authors

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The 19 states included in our analysis are: Assam, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Odisha, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal. The sample excludes regions raised to statehood in the years 2000 and beyond with Mizoram, the newest state in our sample, having the fewest number state elections at 8. Jammu and Kashmir is the only large Indian state with a longer electoral history omitted from our sample. This is because in Jammu and Kashmir elections are held every 6 years as opposed to 5 years in other Indian states, and are often held amid heavy security, usually with low voter turnout. Governance and electoral cycles in Jammu and Kashmir are often interrupted due to frequent interventions by the central government.

Diwakar (2007) studied Duverger’s prediction at the national level. State constituencies are much smaller than national counterparts—on an average, 6 to 7 state electoral constituencies form one national electoral constituency. Dash et al. (2019) have shown that Duverger’s prediction is violated even at the state level.

The number of parties in this study is taken as the number of parties appearing in the “List of Participating Parties” in the summary statistical report presented by the Electoral Commission of India on each Assembly election (excluding independents). The number of entering parties is then the number of new party names appearing in this list and the number exiting is the number of party names not continuing into the next election. An accurate description of what a ‘truly new’ party is is difficult because smaller fringe parties frequently split only to remerge later under different names. Similarly, many small parties drop out only to reappear later. Note that it is not unusual for an Indian state election to feature more than 100 parties. See the Data Appendix, Table 4, for descriptive statics.

Incomplete coverage and omissions in the data result in 236 elections comprising the final data set.

The data used in this paper is available online through Scholars Portal in Dataverse. See the Data appendix for greater detail.

See Miazzo, Moser and Scheiner (2018) for establishing the applicability of heterogeneity concerns for countries operating under first-past-the-post election rules.

See Ferris and Voia (2020) for the application of such a stopping rule to party exit and party lifespans in Canada.

The registration cost of setting up a political party in India is minimal (resulting in over 1600 political parties). Registration requires: a payment of non-refundable 10,000 Rupees ($140.40 US), support of at least 100 recorded members with affidavits of stamp paper of at least 2 rupees, registration of the party’s constitution and current operating officers and the annual audit party funds. Amended Guidelines for Party Registration, online at https://eci.gov.in/candidate-political-parties/political-parties-registration/. This does not imply that the setup time and personal expenditure costs to party members are not substantial.

ENPj = \(\frac{1}{\sum {v}_{ij}^{2}}\), where \({v}_{i}\) is the vote share of each political party, i = 1, 2, …N, in state j. Our measure follows Dash et al. (2019) by defining a political party as any registered party in the top ten vote receiving parties over three successive elections or receives more than 8 percent of the vote in any one election (all other parties and individual candidates included in a composite grouping, other). Winer et al (2019) use electoral data up to 2013 and the data is available at https://dataverse.scholarsportal.info/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.5683/SP2/N3GJR4. We have updated that dataset for state elections through 2018.

Constituency density is defined as the number of registered state voters divided by the number of seats in the state assembly. The Constitution of India states only that a State Legislative Assembly must have no less than 60 and no more than 500 members (with exceptions granted by an Act of Parliament in cases of Goa, Sikkim, Mizoram).

The post-independence Indian constitution created a reservation provision for disadvantaged minority groups. Religion, however, is not used as a basis for political reservation. The percentage of seats reserved for SCs and STs in both federal and state legislatures is based on their population shares. The number of reserved seats and their share in the total seats changes when a state is bifurcated, a new set of delimitation commission’s recommendations are implemented, or when the definition of SC or ST changes. Definition of SCs and STs were made uniform within a state with the implementation of the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Orders Act of 1976 in 1977. For many states seat reservation stays constant across multiple elections. See Chin and Prakash (2011) for a more detailed discussion.

To measure religious diversity, we used a Herfindahl index of denominational affiliation, interpolated between censuses and averaged over the previous governing period. Because of its high correlation with seat reservation and because more political parties use caste rather than religion to build party support, we used seat reservation rather than religious frag in our regression analysis.

Comparing the electoral outcomes in constituencies with reserved versus non-reserved seats, Auerbach and Ziegfeld (2020) found the crowding out of candidates and the focusing of competition on the major parties minor parties in constituencies with reserved seats while Mori and Kurosaki (2011) found voter turnout lower in reserved constituencies. Focusing only on reserved SC constituencies, Jensenius (2017) found lower numbers of candidates contesting elections, higher vote margins of victory, and lower turnout rates compared to unreserved ones. These studies focus on the impact of electoral reservation at the constituency level, we study reservation’s effects on party structure at the assembly level.

See Dassonneville (2017, p.137).

In earlier work we also used urbanization as a heterogeneity measure because of its wide variation across Indian states and over time. However, there is no current consensus on how the urban–rural split is expected to affect electoral participation [for recent work Stockemer and Blais (2019) and McAllister and Muller (2018)] and urbanization was found to be insignificant in all forms of our test.

Between 1967 and 1983, there had been more than 2700 cases of party defections, which brought down over 16 state Governments. See Sethia (2019, p.25) who acknowledges Stanley A Kochanek, ‘Mrs. Gandhi’s Pyramid: The New Congress’ in Zoya Hasan (ed.), Parties and Party Politics in India (Oxford University Press 2004, p78).

The election Symbols Order of 1968 sets any one of five conditions that need to be satisfied for State Party status: secure at least 6% of the valid vote and win at least 2 seats in a (Vidhan Sabha) Assembly Election; secure at least 6 percent of the valid vote and win at least 1 seats in a (Lok Sabha) General Election; win at least 3 percent of the seats or at least 3 seats, whichever is more, in an Assembly Election; win at least 1 out of every 25 seats from a state in a General Election; or secure at least 8 percent of the total valid vote in an Assembly or a General Election. There are a similar set of national conditions set for recognition as a National party.

As of 2016 there were 7 National parties and more than 50 State parties versus more than 2300 registered parties that were unrecognized.

We allow the real value of the deposit fee to fall by half by 2018.

Yadav and Palshikar (2003) provide a detailed account of party system evolution and electoral politics in Indian states.

One of our states, Assam, was subdivided three times to form the new states of Nagaland (1963), Meghalaya (1972) and Mizoram (1987). To reflect the successive subdivisions, we increased the state creation dummy for Assam by 1 for each occurrence. The state of Punjab underwent a major wave of reorganization in 1966 with Haryana formed as a separate state, Chandigarh converted to a Union territory, and territories were transferred to Himachal Pradesh. Since all these changes took place in the same year, we treat these as one discrete change for the Punjab. In 2000, three new states—Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and Uttarakhand—were carved out of three of the largest Indian states—Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh. State creation dummies account for these changes. In 2014 the new state Telangana was created out of Andhra Pradesh. The process of state creation, however, was completed months after the 2014 assembly election. Since the 2014 election was held in the undivided state of Andhra Pradesh, the creation of Telangana state does not affect our dataset.

Note that the coefficient estimates in a Poisson ‘count’ regression are interpreted as the difference in the logs of the predicted variable for a unit change in the predictor variable, given that the other predictor variables in the model are held constant.

Number of elections varies between 8 in Mizoram and 16 in Uttar Pradesh. The difference is attributable to different lengths to legislative sessions and new state creation– the state of Bombay was divided into Gujarat and Maharashtra in 1960 and the first elections in these states were held in 1962. Haryana was carved out of Punjab in 1966 and its first election was in 1967. Mizoram is the last state entering our panel in 1987.

There is nothing significant about the starting point used for the beginning our 5-year cycles (1955). Changing the starting point by a year or two backward or forward does not change our results much. As an alternative to election cycle time dummies, we also used the state election number as a covariate in our model and found similar results.

Jensenius (2017) has used a similar approach.

Because the number of political parties is not stationary over time, we ran a set of panel cointegration tests on party numbers and the first six continuous independent variables (using SC and ST reservation proportions) in Eq. (3). The Kao and Pedroni tests reject the hypothesis of no cointegration among these variables. This implies the existence of a long run stable relationship among these variables.

All Poisson panel models use fixed state effects and are presented with and without election (cycle) effects.

Log likelihood statistic is a better measure of the goodness of fit test. Though a higher Log likelihood statistic for ENP might suggest that the ENP model has a better fit, the statistics are not directly comparable as the scales of the dependent variables are different (see the data appendix, Table 4, for the descriptive statistics).

While the Poisson form of the test is more appropriate for the discreteness of party numbers, a linear version of the model better suits the continuity of positive real numbers in ENP. For this reason, we produce a linear version of the model in Table 5 in the Data Appendix where the results closely resemble the Poisson results of Table 1 and illustrate that our baseline results are robust to an alternative estimator. One significant difference is that both reservation classes are found to significantly negative in their effect on party numbers. To further check the robustness of Table 1’s results, we have estimated results using an alternative strategy: state election years are used as an explanatory variable in place of the election cycle time dummies. These results closely resemble the results of Table 1 and are available upon request.

Note that because of the high collinearity between seat reservation and religion frag, religion frag was dropped from the analysis.

SCs have both a higher average proportion of assembly seats (.153 versus .07) with smaller dispersion across states (.052 versus .077) than do STs.

The significant fall in ENP as the number of seats reserved for scheduled castes rises suggests that the fall in party numbers also concentrates support among a smaller number of larger parties.

Note that while multicollinearity may seem to be a concern with these variables, old, the share of the vote received by Congress and seat reservation proportion are not highly correlated with: $$\rho ($$ congress votes and percentage old) = -.233; $$\rho ($$ percentage old and reserved seat proportion) = -0.389 and $$\rho $$ (congress votes and reserved proportion) = .078.

BIMAROU states have a larger proportion of seats reserved for scheduled castes than do non-BIMAROU states (17 to 12 percent) whereas non-BIMAROU states have a higher proportion of seats reserved for members of scheduled tribes (19 to 12 percent).

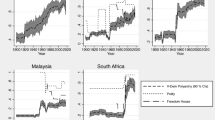

The low/high income grouping divides states into a 9 versus 10 groups, where the low income grouping include the states of Assam, Himachal Pradesh, Mizoram and Nagaland as well as the BIMAROU states.

BIMAROU and non-BIMAROU distinction is usually studied in the context of 14 major and non-special category Indian states: Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal. Restricting our analysis to the sample of these 14 major states produces similar results to Table 3’s. These results are available on request.

The results presented use both state and election cycle fixed effects. The results when using only state fixed effects are similar and available on request.

Examples of electorally successful parties formed from scheduled groups include the Samajwadi Party and the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) that have relied on the support of ‘backward classes’, particularly in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. The Rashtriya Janata Dal governments in Bihar are additional examples where ‘backward classes and Muslin groups were formed for electoral success.

There is some controversy in the literature over whether the political reservation system has increased redistribution in favour of disadvantaged groups and/or government size. Pande (2003) argues that the changes are primarily away from general redistributed programs towards more targeted ones. On the other hand, Zuber (2015, p.391) argues that “if minority representatives are overwhelmingly members of multi-ethnic parties, as in the case of India, redistribution along party lines only benefits groups targeted with reserved seats inter alia, but not specifically, so no systematic effect is obtained.”.

References

Aldrich, J. H. (1995). Why Parties? The Origin and Transformation of Political Parties in America. The University of Chicago Press.

Amorim-Neto, O., & Cox, G. W. (1997). Electoral institutions, cleavage structures, and the number of parties. American Journal of Political Science, 41(1), 149–174.

Auerbach, A. M., & Ziegfeld, A. (2020). How do electoral quotas influence political competition? Evidence from municipal, state, and national elections in India. Journal of Politics, 82(1), 397–401.

Berrington, H. (1985). Why some live and most die. International Political Science Review, 6(4), 441–461.

Bhattacharya, K., & Mitra, S. (2014). More can be less: Hyper plurality of candidates, the rationality of electoral choice, and need for electoral reform in India. India Review, 13(1), 15–39.

Bolleyer, N., & Bytzek, E. (2017). New party performance after breakthrough: Party origin, building and leadership. Party Politics, 23(6), 772–282.

Brancati, D. (2008). The Origins and Strengths of Regional Parties. British Journal of Political Science, 38(1), 135–159.

Chhibber, P. K., & Petrocik, J. R. (1989). The Puzzle of Indian Politics: Social Cleavages and the Indian Party System. British Journal of Political Science, 19(2), 191–210.

Chhibber, P. K., & Kollman, K. (1998). Party aggregation and the number of parties in India and the United States. American Political Science Review, 92(2), 329–342.

Chhibber, P. K., Jensenius, R. J., & Suryanatayn, P. (2014). Party Organization and Party Proliferation in India. Party Politics, 20(4), 489–505.

Chhibber, P. K., & Verma, R. (2018). Ideology and Identity: The changing party systems of India. Oxford University Press.

Chin, A., & Prakash, N. (2011). The redistributive effects of political reservation for minorities: Evidence from India. Journal of Development Economics, 96(2), 265–277.

Church, R. (1984). The pattern of state politics in Indira Gandhi's India. In John R Wood (Eds.), State politics in contemporary India: Crisis or continuity? Boulder, Westview.

Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Rehabilitating Duverger’s theory: Testing the mechanical strategic modifying effects of electoral laws. Comparative Political Studies, 39(6), 679–708.

Cox, G. (1997). Making Votes Count: Strategic Coordination in the World’s Electoral Systems. Cambridge University Press.

Dash, B. B. & Ferris, J. S. (2020). Economic performance and electoral volatility: Testing the economic voting hypothesis on Indian states, 1957–2013. Party Politics, https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820923706.

Dash, B. B., Ferris, J. S., & Winer, S. L. (2019). The measurement of electoral competition, with application to Indian states. Electoral Studies, 62, 1070.

Dassonneville, R. (2017) “Age and voting”, in Arzheimer, K., J. Evans and M.S. Lewis-Beck (eds) The Sage Handbook of Electoral Behaviour Los Angeles: Sage Publications (Chapter 7, 137–158).

Diwakar, R. (2007). Duverger’s Law and the size of the Indian party system. Party Politics, 13(5), 539–661.

Duverger, M. (1959). Political parties: Their organization and activity in the modern state. Methuen & Co.

Ferris, J. S., & Voia, M. (2020). Political Parties in Canada: What determines their entry, exit and turnover? Party Politics, 26(5), 543–554.

Ferris, J.S., S.L. Winer, and D.E.H. Olmstead (2018). A Dynamic Model of Political Party Equilibrium. Carleton Economic Papers #18–04.

Forand, J. G., & Maheshri, V. (2015). A dynamic Duverger’s Law. Public Choice, 165, 285–306.

Ghosh, S. (2016). A quality of growth index: Evidence from Indian States. South Asia Economic Journal, 17(1), 133–148.

Grofman, B., Bowler, S., & Blais, A. (2009). Duverger’s Law of Plurality Voting the logic of party competition in Canada, India, the United Kingdom and the United States. Springer.

Harmel, R., & Roberston, J. D. (1985). Formation and success of new parties: A cross-national analysis. International Political Science Review, 6(4), 501–523.

Harriss, J. (1999). Comparing political regimes across Indian states: A preliminary essay. Economic and Political Weekly, 34(48), 3367–3377.

Hug, S. (2000). Studying the electoral success of new political parties. Party Politics, 6(2), 187–197.

Jaffrelot, C. (2012). Caste and political parties in India: Do Indians vote their caste—while casting their vote? In A. Kohli and P. Singh (Eds.), Routledge handbook of Indian politics. Routledge, New York.

Jensenius, F. (2017). Social justice through inclusion: The consequences of electoral quotas in India. Oxford University Press.

Jones, M. P. (2004). Electoral institutions, social cleavages, and candidate competition in presidential elections. Electoral Studies, 23(1), 73–106.

Kaplan, D., & Venezky, R. L. (1994). Literacy and voting behavior: A bivariate probit model with sample selection. Social Science Research, 23(4), 350–367.

Kapoor, S., & Magesan, A. (2018). Independent candidates and political representation in India. American Political Science Review, 112(3), 678–697.

Kothari, R. (1970). Politics in India. Little Brown.

Lago, I., & Martinez, F. (2011). Why new parties? Party Politics, 17(1), 3–20.

Laroze, D. (2017). Party collapse and new party entry. Party Politics, 25(4), 559–568.

Lucardie, P. (2007). Pristine purity: New political parties in Canada. American Review of Canadian Studies, 39(3), 283–300.

McAllister, I., & Muiller, D. (2018). Early voting, election campaigning and party advantage in Australia. Electoral Studies, 52(1), 103–110.

Meyer, T. M., & Miller, B. (2015). The niche party concept and its measurement. Party Politics, 21(2), 259–271.

Milazzo, C., Moser, R. G., & Scheiner, E. (2018). Social diversity affects the number of parties even under first-past-the-post rules. Comparative Political Studies, 51(7), 9387–9974.

Mishra, A., & Mishra, V. (2018). Is there conditional convergence in the per capita incomes of BIMAROU states in India? Economic Modelling, 70(3), 429–437.

Mori, Y., & Kurosaki, T. (2011). Does political reservation affect voting behavior? Empirical evidence from India. Working paper.

Mulligan, C. B., & Tsui, K. K. (2015). Political entry, public policies, and the economy. Research in Economics, 69(3), 377–397.

Nikolenyi, C. (2008). Recognition rules, party labels and the number of parties in India. Party Politics, 14(2), 213–222.

Nishikawa, M. (2010). Electoral and party system effects on ruling party durability. Party Politics, 18(5), 633–652.

Ordeshook, P. C., & Shvetsova, O. V. (1994). Ethnic heterogeneity, district magnitude and the number of Parties. American Journal of Political Science, 38(1), 100–123.

Pande, R. (2003). Can mandated political representation increase policy influence for disadvantaged minorities. American Economic Review, 93(4), 1132–1151.

Powell, E. N., & Tucker, J. S. (2014). Revisiting electoral volatility in post-communist countries: New data, new results, and new approaches. British Journal of Political Science, 44(1), 123–147.

Prakash, N., Rockmore, M., & Uppal, Y. (2019). Do criminally accused politicians affect economic outcomes? Evidence from India. Journal of Development Economics, 141, 102370.

Riker, W. (1982). The two-party system and Duverger’s law: An essay on the history of political science. American Political Science Review, 76, 753–766.

Sethia, A. (2019). Where’s the party? Towards a constitutional biography of political parties. Indian Law Review, 3(1), 1–32.

Sikk, A. (2005). How unstable? Volatility and the genuinely new parties in Eastern Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 44(4), 391–412.

Spoon, J., & West, K. J. (2015). Alone or together? How party institutions affect party entry in presidential elections in Europe and South America. Party Politics, 21(3), 393–403.

Stockemer, D., & Blais, A. (2019). Voters and Abstainers in National and European Elections. European Review, 27(2), 300–315.

Taagepera, R., & Grofman, B. (1985). Rethinking Duverger’s Law: Predicting the effective number of parties in plurality and PR systems—Parties minus issues equals one. European Journal of Political Research, 13(4), 341–352.

Tavits, M. (2006). Party system change. Party Politics, 12(1), 99–119.

Tavits, M. (2008). Party Systems in the Making: The emergence and success of new parties in New Democracies. British Journal of Political Science, 38(1), 113–133.

Uppal, Y. (2009). The disadvantaged incumbents: Estimating anti-incumbency effects in Indian state legislatures. Public Choice, 138(1–2), 9–27.

Winer, S. L., Ferris, J. S., & Dash, B. B. (2019). Replication data for The measurement of electoral competition, with application to Indian states. At Scholars Portal Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.5683/SP2/N3GJR4

Winer, S. L., Ferris, J. S., Dash, B. B., & Chakraborty, P. (2021). Political competitiveness and the private-public structure of public expenditure: A model and empirics for the Indian States. International Tax and Public Finance, 28(6), 1430–1471.

Yadav, Y., & Palshikar, S. (2003). From hegemony to convergence: Party system and electoral politics in the Indian States, 1952–2002. Journal of Indian School of Political Economy, 15(1–2), 5–44.

Zuber, C. I. (2015). Reserved seats, political parties, and minority representation. Ethnopolitics, 14(4), 390–403.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Data sources

Election Commission of India (ECI) publishes state election results and statistics at https://eci.gov.in/statistical-report/statistical-reports/. Data is organized by state and election year. Information on number of constituencies, reserved constituencies (total, SCs, and STs), registered voters, and registered parties and their vote shares from these reports are used to construct the electoral variables.

Central Statistical Organization (CSO), Government of India, publishes the year-wise official figures of State GDP, per capita income, and growth rates. This information is used to estimate growth rates and per capita income over the electoral tenure.

Census of India provides state-wise information on urbanization, literacy rate, and religious and age composition of population once in a decade starting from 1951. The latest census figures are available till 2011 and we have used the World Bank’s data to extend our data from 2011 to 2018. Because the World Bank figures are available only at the national level we assumed that the difference between national and state figures in the 2011 census persisted to generate state-wise figures through 2018. Data for non-census election years are generated by interpolating between census years and the averages figures over the electoral tenure are finally used.

The Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, which lays out conditions for party recognition is available at https://legislative.gov.in/electionlawsrelated/election-symbols-reservation-and-allotment-order-1968

The anti-defection law, passed as the 52nd Constitution Amendment Act, 1985, is available at https://legislative.gov.in/constitution-fifty-second-amendment-act-1985

The 61st Constitution Amendment Act, 1988, reducing voting age from 21 to 18 years is available at https://legislative.gov.in/constitution-sixty-first-amendment-act-1988

Election Commission of India’s decision to increase in security deposit for contesting candidates is available at https://eci.gov.in/faqs/elections/contesting-for-elections/faqs-contesting-for-elections-r4/

Years and numbers of state reorganization acts are available at https://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/Chronological%20List%20July%202021.pdf

An Excel file of the full dataset together with figures showing the number of parties, number entering and exiting and the effective number of parties (ENP) is available at:

Ferris, Stephen, 2021, “Replication Data for: On the Structure of the Political Party System in Indian States, 1957–2018”, https://doi.org/10.5683/SP2/OTR55V, Scholars Portal Dataverse.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferris, J.S., Dash, B.B. On the structure of the political party system in Indian states, 1957–2018. Const Polit Econ 34, 1–35 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-021-09358-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-021-09358-2

Keywords

- Number of political parties

- ENP

- Indian states

- Entry and exit of political parties

- BIMAROU and Non-BIMAROU states

- Fixed effects Poisson panel estimation