Abstract

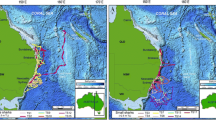

We present a compilation of published telemetric results, complemented by the addition of new results where necessary, to justify the expansion of the marine protected areas in the Eastern Pacific. In addition, we furnish evidence that fishing effort by commercial vessels, carrying position-monitoring, satellite-communicating radio beacons, has diminished within their boundaries. Researchers have described the movement ecology of nine species of sharks at these insular sites: the Galapagos archipelago off Ecuador, Malpelo Island off Colombia, Cocos Island off Costa Rica, and the Revillagigedo archipelago off Mexico. Mainly two telemetric techniques have been utilized: (1) placing coded ultrasonic beacons on individuals and detecting their presence with autonomous receivers deployed along the coasts of the islands and (2) outfitting individuals with SPOT and PSAT tags: the former enabling the ARGOS satellite to detect surface-swimming individuals, the latter releasing from individuals and rising to the surface to transmit geolocation based-positions to the same satellite. This information has enabled Mexico to create the Revillagigedo National Park, Colombia to increase the size of the Malpelo Fauna and Flora Sanctuary, and Costa Rica to create a protective corridor between Cocos and the Las Gemelas seamounts. Satellite tracking of sharks outside the current boundaries of the Galapagos Marine Reserve supports the need to increase its size in the future. Hence, telemetric studies have played and continue to serve an essential role in providing a well-supported rationale for research managers to match the size of their marine reserves to the spatial ecologies of the species within them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

25 March 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-022-01234-8

References

Aldana-Moreno A, Hoyos-Padilla EM, González-Armas R, Galván-Magaña F, Hearn A, Klimley AP, Winram W, Becerril-García E, Ketchum JT (2020) Residency and diel movement patterns of the endangered scalloped hammerhead Sphyrna lewini in the Revillagigedo National Park. J Fish Biol 96:543–548

Banks S (2002) Ambiente físico. In: Danulat E, Edgar GJ (eds) Reserva marina de Galápagos. línea base de la biodiversidad. Fundación Charles Darwin, Parque Nacional Galápagos, SantaCruz, Galápagos, pp. 22–37

Baum JK, Myers RA (2004) Shifting baselines and the decline of pelagic sharks in the Gulf of Mexico. Ecol Lett 7:135–145

Baum J, Myers R, Kehler DG, Worm B, Harley SJ, Doherty PA (2003) Collapse and conservation of shark populations in the Northwest Atlantic. Science 299:389–392

Bessudo S, Soler GA, Klimley AP, Ketchum J, Arauz R, Hearn A, Guzmán A, Galmettes B (2011a) Vertical and horizontal movements of the scalloped hammerhead shark (Sphyrna lewini) around Malpelo and Cocos Islands (Tropical Eastern Pacific) using satellite telemetry. Boletín Investigaciones Marinas Costas 40:91–106

Bessudo S, Soler GA, Klimley AP, Ketchum JT, Hearn A, Arauz R (2011b) Residency of the scalloped hammerhead shark (Sphyrna lewini) at Malpelo Island and evidence of migration to other islands in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. Environ Biol Fish 91:165–176

Brattstrom BH (1990) Biogeography of the Islas Revillagigedo, Mexico. J Biogeogr 17:177–183

Burgess GH, Beerkircher LR, Cailliet GM, Carlson JK, Cortés E, Goldman KJ, Grubbs RD, Musick JA, Musyl MK, Simpfendorfer CA (2005) Is the collapse of shark populations in the Northwest Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico real? Fisheries 30:19–26

Chávez EJ, Arauz R, Hearn A, Nalesso E, Steiner T (2020) Asociación de tiburones con el Monte Submarino Las Gemelas y primera evidencia de conectividad con la Isla del Coco, Pacífico de Costa Rica. Rev Biol Trop 68(Supl 1):320–329

Comisión Nacional de Ȧreas Naturales Protegidas [CONANP] (2017) Estudio Previo Justificativo para la declaratoria del Parque Nacional Revillagigedo. Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas, Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. México, pp. 214 (including three addendums)

Genin A (2004) Bio-physical coupling in the formation of zooplankton and fish aggregations over abrupt topographies. J Mar Syst 50:3–20

Graham J (1975) The biological investigation of Malpelo Island: introduction. In: Graham JB (ed) The Biological Investigation of Malpelo Island, Colombia. Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, pp 1–8

Hamner WM, Hauri IR (1981) Effects of island mass: water flow and plankton pattern around a reef in the Great Barrier Reef lagoon, Australia. Limnol Oceanogr 26:1084–1102

Hearn A, Ketchum J, Klimley AP (2010) Hotspots within hotspots? Hammerhead shark movements at Wolf Island in Galapagos Marine Reserve. Mar Biol 157:1899–1915

Hearn AR, Green JR, Roman R, Acuña D, Espinoza E, Klimley AP (2016) Adult female whale sharks make long distance movements past Darwin Island (Galapagos, Ecuador) in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. Mar Biol 163:14–26

Holland K, Brill RW, Chang RKC (1990) Horizontal and vertical movements of yellowfin and bigeye tuna associated with fish aggregating devices. Fish Bull US 88:493–507

Holland KN, Grubbs R D (2007) Chapter 10: Fish visitors to seamounts Section A: tunas and billfish. In: T. Pitcher, T. Morato, P. Hart, M. Clark, N. Haggan and R. Santos, (eds). Seamounts: ecology, fisheries & conservation. Blackwell Publishing, Fish and Aquatic Resources Series 12, Oxford, pp 189–207

Houvenaghel GT (1984) Oceanographic setting of the Galápagos Islands. In: Perry R (ed) Galapagos (Key Environments). Pergamon Press, Oxford, pp 43–54

Jacoby DM, Ferretti F, Freeman R, Carlisle AB, Chapple TK, Curnick DJ, Dale JJ, Schallert RR, Tickler D, Block BA (2020) Shark movement strategies influence poaching risk and can guide enforcement decisions in a large, remote marine protected area. J Appl Ecol 57:1782–1792

Ketchum JT, Hearn A, Klimley AP, Peñaherrera C, Espinoza E, Bessudo S, Soler G, Arauz R (2014a) Seasonal changes in movements and habitat preferences of the scalloped hammerhead shark (Sphyrna lewini) while refuging near an oceanic island. Mar Biol 161:755–767

Ketchum JT, Hearn A, Klimley AP, Peñaherrera C, Espinoza E, Bessudo S, Soler G, y Arauz R (2014b) Inter-island movements of scalloped hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna lewini) and seasonal connectivity in a marine protected area of the Eastern Tropical Pacific. Mar Biol 161:939–951

Ketchum JT, Hoyos-Padilla M, Aldana-Moreno A, Ayres K, Galván-Magaña F, Hearn A, Lara-Lizardi F, Muntaner-López G, Grau M, Trejo-Ramírez A, Whitehead D, Klimley AP (2020) Shark movement patterns in the Mexican Pacific: a conservation and management perspective. Adv Mar Biol 85:1–37

Klimley AP (1993) Highly directional swimming by scalloped hammerhead sharks, Sphyrna lewini, and subsurface irradiance, temperature, bathymetry, and geomagnetic field. Mar Biol 117:1–22

Klimley AP, Nelson DR (1984) Diel movement patterns of the scalloped hammerhead shark (Sphyrna lewini) in relation to El Bajo Espiritu Santo: a refuging central-position social system. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 15:45–54

Klimley AP, Richert JE, Jorgensen SJ (2005) The home of blue water fish. Am Sci 93:42–49

Klimley AP, Ketchum JT, Lara-Lizardi F, Papastamatiou Y, Hoyos-Padilla ME (2021) Evidence for spatial and temporal resource partitioning at sharks at Roca Partida, an isolated pinnacle in the eastern Pacific. Environ Biol Fish (in press)

Kroodsma DA, Mayorga J, Hochberg T, Miller NA, Boerder K, Ferretti F, Wilson A, Bergman B, White TD, Block BA, Woods P, Sullivan B, Costello C, Worm B (2018) Tracking the global footprint of fisheries. Science 359:904–908

Lizano OG (2008) Dinámica de aguas alrededor de la Isla del Coco, Costa Rica. Rev Biol Trop 56:31–48

Nalesso E, Hearn A, Sosa-Nishizaki O, Steiner T, Antoniou A, Reid A, Bessudo S, Soler G, Klimley AP, Lara F, Ketchum J, Arauz R (2019) Movements of scalloped hammerhead sharks Sphyrna lewini at Cocos Island, Costa Rica, and between oceanic islands in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. PLoS ONE 14(3):e0213741

O’Leary BC, Ban NC, Fernandez M, Friedlander AM, García-Borboroglu GY, Guidett P, Harris JM, Hawkins JP, Langlois T, McCauley DJ, Pikitch EK, Richmond HR, Roberts CM (2018) Addressing criticisms of large-scale marine protected areas. Bioscience 68:359–370

Pacoureau N, Rigby C, Kyne P, Sherley RB, Winker H, Carlson JK, Fordham SV, Barreto R, Fernando D, Francis M, Jabado RW, Herman KB, Liu K, Marshall AD, Pollom RA, Romanov EV, Simpfendorfer CA, Yin JS, Kindsvater HK, Dulvy NK (2021) Half a centry of global decline in oceanic sharks and rays. Nature 589:567–571

Palacios DM (2004) Seasonal patterns of sea-surface temperature and ocean color around the Galapagos: regional and local influences. Deep Sea Res Part II 51:43–57

Roberts C (2003) Our shifting perspectives on the oceans. Oryx 37:166–177

Simpfendorfer CA, Tobin AJ (2015) Contrasting movements and connectivity of reef-associated sharks using acoustic telemetry: implications for management. Ecol Appl 25:2101–2118

Stevenson C, Katz LS, Micheli F, Block B, Heiman KW, Perle C, Weng K, Dunbar R, Witting J (2007) High apex predator biomass on remote Pacific islands. Coral Reefs 26:47–51

White TD, Ong T, Ferretti F, Block BA, McCauley DJ, Micheli F, De Leo GA (2020) Tracking the response of industrial fishing fleets to large marine protected areas in the Pacific Ocean. Cons Biol 34:1571–1578

Wilson SG, Stewart BS, Polovina JJ, Meekan MG, Stevens JD, Galuardi B (2007) Accuracy and precision of archival tag date: a multiple-tagging study conducted on a whale shark (Rhincodon typus) in the Indian Ocean. Fish Oceanogr 16:547–554

Yuen HSH (1970) Behavior of skipjack tuna, Katsuwonis pelamis, as determined by tracking with ultrasonic devices. J Fish Res Bd Can 27:2071–2207

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our appreciation to Galo Quezada and Washington Tapia, who provided the permit (Klimley PC-37-11) to conduct tagging studies in the Galapagos National Sanctuary. Eduardo Espinosa and Harry Reyes are thanked for overseeing for the Parque National Galapagos the research that was completed in the Galapagos archipelago. Many researchers helped in both the tagging and analysis of the resulting detection data, particularly Frida Lara-Lizardi, Robert Rubin, and Alex Antoniou of Fins Attached provided ship time and funds for the purchase of acoustic and satellite tags as well as autonomous receivers. Scott Henderson of Conservation International was an early proponent of protecting sharks in the ETP. His input led to the first grant from 2001 to 2003 given by the Committee for Research and Exploration at the National Geographic Society, entitled “Tracking hammerhead sharks for creation of marine reserves” (principal investigator: senior author). That was followed by grants to the same investigator in 2007–2008, 2007–2008, 2009, and 2012. Additional funding for the tagging studies was provided by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation in 2004–2005, the Whitley Fund for Nature from 2005 to 2015, the World Wildlife Fund in 2007–2008, the International Community Foundation in 2009–2010, Conservation International in 2010–2011, the Galapagos Conservancy in 2010–2011 and 2011–2012, and Iris and Michael Smith in 2018-2020. Randal Arauz and George Shillinger obtained funding from private donors for research studies conducted at Cocos and the Galapagos Islands, respectively. This work was completed under the auspice of two Animal Care Protocols obtained by the senior author at the University of California, Davis: (1) 12140 — “Tracking hammerhead sharks for creation of marine reserves” and (2) 16022 — “Tracking sharks in the open ocean.” The acoustic tag detections and satellite tracks presented in this article are curated by CPP at MigraMar, local data for (1) the Revillagigedos Islands are present in a database maintained by Pelagios Kakunjá, (2) the detections at Cocos Island are in a database kept by Centro de Rescate de Especies Marinas Amenazadas (CREMA) and the Ocean Tracking Network (OTN), (3) files of acoustic detections and satellite tracks for Malpelo Island are present in a database maintained by Fundación Malpelo y Otros Ecosistemas Marinos, and (4) the acoustic detections for the Galapagos archipelago are present in the database of OTN and satellite tracks for the Galapagos archipelago are under curatorship of ARH at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The contributions of the authors to the manuscript are given in the following work statement. APK planned studies, secured funding, participated in field work and analyses, wrote relevant article, reviewed this manuscript; RA secured funding, participated in field work and analyses; SB planned studies, secured funding, participated in field work and analyses, wrote germane article, reviewed this manuscript; EJC analyzed data, wrote relevant article, reviewed this manuscript; NC conducted analyses of fishing effort in reserves, provided figures, reviewed this manuscript; EE participated in the field work, oversaw research Galapagos Park Service; JG obtained funding, participated in field work; AH, planned studies, secured funding, participated in field work and analyses, wrote relevant article, reviewed this manuscript; MEH participated in field work and analyses, provided data used in figure, reviewed manuscript; EN analyzed data, wrote relevant article, reviewed this manuscript; JTK planned studies, participated in field work and analyses, wrote relevant article, reviewed this manuscript; CF provided funding for tagging sharks at the Revillagigedos Islands, Cocos Island, and the Galapagos Islands, offered feedback on the proposals, tagged sharks at the three islands, plotted tracks of tiger sharks, displayed tracks of tiger shark on the OCEARCH website; FL tagged sharks with ultrasonic and satellite transmitters at Malpelo Island, kept database of tagging data, provided data to APK during writing of article; GS secured funding for research activities in the Galapagos Islands, tagged sharks with pop-up satellite archival tags (PSATS) and smart position or temperature transmitting (SPOT) tags, trained colleagues in the Galapagos Islands in the fin-attachment satellite tagging technique, analyzed data from Galapagos shark satellite tagging efforts, published data from the Galapagos Islands shark tagging effort in at least three different publications, including a book chapter with several MigraMar coauthors, provided data, images, analyses, and editorial content in support the justification for the Galapagos Marine Reserve; GS tagged sharks with ultrasonic transmitters at Malpelo Island, analyzed data from tagged sharks, helped prepare figures, and helped write two papers, from which figures were used in manuscript; TS secured funding for research activities at Cocos Island from a private source, made 19 cruises to Cocos and the Galapagos Islands, tagged sharks at Cocos Islands, helped in the production of the major paper on shark movements at Cocos Island; CP oversaw analyses of fishing effort in reserves, provided figure of satellite tracks, and reviewed this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All sources of funding for these studies are acknowledged within the review. Animal Care Protocols for the tagging pelagic sharks were obtained from the University of California, Davis’ Animal Care Committee, which includes four certified veterinarians. The references for the protocols are given within the manuscript. The databases with acoustic tag detections and satellite tracking are identified in the Acknowledgements. Copyright permissions for three figures published earlier by the authors that are discussed in this review paper will be obtained from the Copyright Clearing House, contingent upon the article being accepted for publication. All authors have read the manuscript, made editorial contributions, and are willing to be listed as authors on this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: Modifications have been made to the Author Group, Acknowledgements, and Author contribution sections. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Klimley, A.P., Arauz, R., Bessudo, S. et al. Studies of the movement ecology of sharks justify the existence and expansion of marine protected areas in the Eastern Pacific Ocean. Environ Biol Fish 105, 2133–2153 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-021-01204-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-021-01204-6