Abstract

This paper distinguishes between formal and informal entrepreneurship. It theorises that each are influenced by very different combinations of macro-economic factors and strongly moderated by country income levels. Empirically, we show the ease of starting a business and high-quality governance, exert a powerful influence on formal, but not informal entrepreneurship. The latter is influenced by self-employment rates in low-income countries and by female labour force participation in high-income countries. Policy-makers seeking to improve economic welfare through enhancing entrepreneurship therefore have to choose the ‘type’ of entrepreneurship on which to focus and then select appropriate policies. By providing a novel grouping of these policies, we are able to assist them in making these choices.

Plain English Summary

Policy-makers: Decide what type of entrepreneurship you want for your country and, only then, choose your policies, because ‘one size doesn’t fit all.’ Entrepreneurs come in all shapes and sizes, ranging from informal street market traders on the one hand to formal tech giants in majestic offices on the other. The view of most governments is that entrepreneurship is ‘good’ because it not only provides employment for the market trader and for the tech giant, but also for many others in the economy. Governments therefore spend taxpayers’ money funding entrepreneurs to start and grow their businesses, but this raises two key questions: first, should it be the formal tech giant, or the informal street trader, that receives public funds and second, how should these be provided? Our conclusion, based on evidence from more than 80 high- and low-income countries, is that effective policy not only has to take account of the formal/informal distinction and the income level of the country, but also how that policy is delivered. We show that, in low-income countries, formal entrepreneurship is more likely to be enhanced by state policies to promote education and female activity rates; it is less likely to be stimulated by the creation of more enterprises. This is because relatively few informal enterprises subsequently make the transition to formality and to significant job creation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

There is now clear evidence that the scale of entrepreneurship varies considerably between countries (Klapper et al., 2010); there is also a second body of empirical work that links these cross-country variations to differences in institutional frameworks (Aidis et al., 2012; Van Stel et al., 2007). This link is important because of a third, more contentious, body of work that links the scale and nature of entrepreneurship to economic growth (Carree & Thurik, 2010). The inference is that the nature of institutions influences entrepreneurship (Autio et al., 2013) which, in turn, influences economic welfare (Urbano et al., 2019). There is therefore a powerful policy-based case for investigating the nature of these links.

The theory-based case has been somewhat less well-developed, but manyFootnote 1 consider it was Baumol (1990) who first distinguished between different ‘types’ of entrepreneurship—productive, unproductive, and destructive. He argued that the incentives and disincentives provided by institutions influenced whether, at a point in time, individuals were entrepreneurs or non-entrepreneurs and also the ‘type’ of entrepreneurship in which they engaged. In this spirit, Young et al. (2018) recently found that the institutional framework also influences the type of entrepreneurial opportunities (imitative versus innovative) that emerge in a country.

This paper follows Baumol by assuming the individual chooses to enter and either remain in, or exit from, a type of entrepreneurship. These choices are influenced, at least in part, by governments because of their role in setting the institutional framework (Bowen & De Clercq, 2008; Dilli et al., 2018). Where we move on from Baumol is by distinguishing between formal and informal entrepreneurship (Autio et al., 2019; Bennett, 2010; Williams et al., 2017). Conceptually, formal entrepreneurship is equated with being registered with the state, but operationally we see it as a limited liability company. All other forms of entrepreneurship are viewed as informal.Footnote 2 In the present paper, we investigate the determinants of country rates of formal and informal entrepreneurship, and whether these differ between high- and low-income countries. The distinction between high- and low-income countries is justified because the size of the informal sector varies with income levels. A recent report by ILO (2019) estimates that, worldwide, 62% of total employment is in the informal sector. This percentage differs considerably across countries, ranging from 85% for the group of low-income countries to 18% for the group of high-income countries (ILO, 2019, p. 15). Hence, particularly in low-income countries, the economic contribution of informal entrepreneurs and their businesses is substantial.

We consider this paper makes five contributions. First, it provides a novel categorisation for governments when making decisions that influence both the scale and type of entrepreneurship. We identify three groups comprising what we refer to as policy instruments. Group 1 are policies that are expected to have an impact on the scale and nature of entrepreneurship in the short to medium term, and over which entrepreneurship policy-makers exert a strong influence. Group 2 are policy instruments that, although they influence the scale and nature of entrepreneurship, are not easily amenable to change by governments, even in the medium term. Group 3 are policies which, although influencing the scale and nature of entrepreneurship, do not have this as a key objective.

Second, we show empirically how the three groups of policies influence entrepreneurship rates, and how this varies between high- and low-income countries and between types of entrepreneurship (formal and informal entrepreneurship).Footnote 3 Third, before doing so, we briefly theorise about the expected sign of each determinant of formal and informal entrepreneurship rates, and in high- and low-income countries, i.e. four different contexts per determinant.Footnote 4 As we consider 12 (potential) determinants in total, this involves 48 expected signs. We believe this is the first study to provide such brief theorising for four different contexts per determinant of macro-level entrepreneurship and for as many as 12 determinants.Footnote 5

Fourth, we provide the first empirical (macro-level) test of the ‘stepping stone’ hypothesis as theorised by Bennett (2010), i.e. that current informal self-employment is a stepping stone to subsequent formal entrepreneurship.

Fifth, we point to the very different roles played by female labour force participation rates in high- and low-income countries and to its impact on formal and informal entrepreneurship.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 distinguishes between formal and informal entrepreneurship; it makes the case that the scale and composition of entrepreneurship is influenced by different factors in high- and low-income countries. Based upon this review, it sets out our expectations of twelve determinants of entrepreneurship in four different contexts as explained above (48 expected signs). Section 3 provides a detailed explanation of how formal and informal entrepreneurship are measured. Section 4 presents results. We conclude in Section 5 by providing a focus for policy-makers and set new challenges for the research community.

2 Formal and informal entrepreneurship

This section sets out the entrepreneurship choices facing both the individual and governments. The former faces two choices; the first is whether or not to become an entrepreneur and, if so, a second choice whether to exercise this option formally or informally. The choices facing governments relate to the creation of an institutional framework which facilitates or inhibits entrepreneurship in general, and its distribution between formal and informal types (Capelleras et al., 2008).Footnote 6

2.1 Individual choice

The occupational choice model of entrepreneurship has a well-established history in economics (Parker, 2018) with individuals choosing between entrepreneurship and other options such as waged employment, retirement or unemployment, based on expected utility in those states.

Our focus is on their second choice which is between performing this role formally or informally. A formal entrepreneur is one whose business is registered with the government authorities, as a result of which he or she incurs tax payments and has to comply with strict and extensive operational, governance and reporting requirements. We view the legal form that best captures formality to be the Limited Liability Company (LLC). All other forms of entrepreneurship that do not satisfy these requirements are classified as informal.Footnote 7

The individual is assumed to assess the costs and benefits of formality and informality. The potential benefits of formality are fourfold. First, only formal businesses are eligible for government funding and support which the owner may believe enhances the survival and growth of the business (Straub, 2005). Second, registration and periodic updating imposes a financial discipline upon the new/small enterprise which also enhances short-term performance (Frankish et al., 2013).Footnote 8 Third, the extra credibility of formality provides reassurance both to customers and to suppliers of trade and bank credit. This makes them more likely to extend forms of credit, so supplementing the financial buffer that enables new and small firms to offset temporal variations in cash receipts (Coad et al., 2016); customers, in turn, have also long seen formality as a proxy for reliability (Freedman & Godwin, 1994). Finally, formality—as in the choice of limited liability status—may reflect the confidence of the owner about the business. Levine and Rubinstein (2017) make the case that the choice of legal form can be considered to be a valid proxy, not only for a confidence and willingness to take risks, but also to achieve subsequent success.

Formality, however, imposes pecuniary and non-pecuniary costs upon an enterprise. The former include not only the eligibility to pay taxes and the direct registration costs but also, for example, any sales foregone imposed by a time-consuming registration process. A third pecuniary cost is that of compliance with legislation—such as the payment of a minimum wage to employees—which can increase the cost base of the enterprise (Bannerji & Jain, 2007). The non-pecuniary costs include the unease characteristic among entrepreneurs in sharing information, perhaps particularly with government, on the grounds that this could leak to competitors (Virglerova et al., 2016).

However, the choice made by the entrepreneur between formality and informality is not fixed and the enterprise can switch. Bennett (2010) theorises a set of circumstances in which a new enterprise begins informally, and then switches to become formal—the so-called ‘stepping stone’. The availability of a low-cost option at start-up means the owner can test the viability of the enterprise. It can be viewed as a pilot, or apprenticeship, that encourages the individual to start, and then either to quit having incurred few costs, to continue informally, or to switch once the uncertainty has reduced.Footnote 9 However, at least in the USA, switchers are comparatively rare (Levine & Rubinstein, 2017).

2.2 Government choices

Governments across the world make different choices in the set-up of their institutions (Fainshmidt et al., 2018). We now examine how these choices influence the scale and nature of entrepreneurship and distinguish between short and long-run effects. In the short run, we assume Government is able to make changes to the institutional framework influencing the scale and nature of entrepreneurship but, only in the longer run, is it able to make structural changes in, for example, the sectoral composition of the economy.

Assume Government A wishes to increase both the number of enterprises in the economy and also the proportion of all enterprises that are formal. It made this decision on the grounds that formal enterprises potentially provide a stream of tax revenue; that they are more likely to comply with environmental legislation, so enhancing social welfare; that they are more likely to comply with health and safety and any minimum wage legislation, so providing a safer and better-paid environment for their employees. It also favours formality on the grounds that such firms are less likely to be constrained in their ability to survive and/or expand by a lack of access to funding. This expansion generates employment and other social benefits.

Government B takes a different view. It places more weight upon the benefits of informality. It argues that, although there may be an increase in tax revenue from formality, there are increased costs of collection and enforcement which may be considerable. It believes registration is a disincentive to expansion, to which firms respond by not expanding beyond the given threshold at which they believe their activities will be detected (Giugale et al., 2000). For this reason, greater formality serves to depress expansion and so reduces potential economic benefits.

We now identify three groups of government policies, decisions on which comprise the institutional framework for entrepreneurship, so influencing its scale and nature. Our approach, in all three policy groups, is to identify variables that capture these policy choices. We set out the rationale for their inclusion and our expectation of their impact on formal and informal entrepreneurship and in high- and low-income economies. All variables referred to in this section are defined in full in Online Appendix Table A1 (available online separately).

Group (i): policies that are expected to change the scale and nature of entrepreneurship in the short to medium term

Two clear policy options are open to government. These are the lowering of business burdens/improving governance and raising rates of self-employment. In both cases, entrepreneurship policy-makers exert a strong influence over the nature and delivery of the policy.

-

Lowering business burdens/improving governance

Djankov et al. (2002) showed the costs and time taken to start a new (formal) business were generally considerably higher in low-, than in high-, income countries. Since then, governments have sought to make it easier to ‘do business’. This is most clearly reflected in reducing the number of days required to register a business and lowering the costs of registration (i.e. a greater ‘ease’ of doing business) and is captured by a higher value of the variable DTF_Starting,Footnote 10 so lowering the costs of starting a formal business. However, because there are no costs of registering an informal business these changes do not directly influence rates of informal business creation (Van Stel et al., 2007).

The expected sign for DTF_Starting on formal entrepreneurship is positive but for informal entrepreneurship the sign is indeterminate, in both high- and low-income countries.

The speed and efficiency of enforcement of legal and financial contracts, together with other measures of good governance captured in the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) index (Kaufmann et al., 2011), are expected to provide confidence to a potential new business owner (Ngobo & Fouda, 2012). Once again, this is likely to primarily benefit formal, rather than informal, enterprises.

The expected sign for WGI index on formal entrepreneurship is positive but for informal entrepreneurship the sign is indeterminate, in both high- and low-income countries.

-

Self-employment

A second policy option for government is to directly encourage self-employment—even if these businesses are not formally registered when they first begin to trade. This is because individuals who are currently self-employed are likely to be more aware of, and have greater confidence in, their ability to manage entrepreneurial opportunities than those without this experience. Initially, such opportunities are likely to be exploited by informal enterprises, but with little impact on the number of formal businesses. However, as noted earlier, a second round effect theorised by Bennett (2010) is that those beginning informally view their new enterprise as a ‘testing of the water’ which, if successful, encourages them to make the stepping-stone to formality.

Alternatively, the individual who has developed a business within the informal economy may be reluctant to leave and, as noted above, direct expansion towards creating new enterprises which operate below the legal minimum threshold of formality. They may even forgo expansion entirely. However (successful), self-employed individuals may act as a role model to other individuals (Bosma et al., 2012) who establish their own—in most cases informal—business.

The expected sign of self-employment on both formal and informal entrepreneurship is positive, in both high- and low-income countries.

Group (ii): factors influencing the scale and nature of entrepreneurship, but which are difficult to change, even in the medium term

The within-country spatial distributions of enterprise rates are strongly persistent over long periods of time (Fritsch and Wyrwich 2014) for two reasons. The first reflects sectoral structures that change only slowly. The second is that aggregate enterprise rates, and their composition, reflect income levels which also change only slowly over time. We now examine evidence of the impact of each.

-

Sectoral composition

In all countries new business creation rates vary considerably by sector (Chenery 1960; Fain 1980). These are generally low in agriculture because farms traditionally pass across the generations, so there are few “new” farms; those wishing to begin a new agricultural enterprise are also required to have access to significant capital. In contrast, rates are high in professional and business services where entry costs can be close to zero and where technology has created new opportunities. The sectoral composition of an economy therefore strongly influences aggregate rates of new business creation. The employment shares of agriculture and services are our two measures of the sectoral composition of the economy.

Since farms usually operate in the informal, rather than the formal, sector in low-income countries: The expected sign of Share agriculture on formal entrepreneurship in low-income countries is negative, but positive for informal entrepreneurship. In high-income countries, farms are formal but entry into farming is rare:

The expected sign of Share agriculture on formal entrepreneurship in high-income countries is indeterminate and negative for informal entrepreneurship. In services, firms are usually small and entry has low barriers:

The expected sign of Share services is positive for both forms of entrepreneurship in both high- and low-income economies.

-

Per capita income

In low-income countries, economic development is associated with a transformation from agriculture to manufacturing which is likely to go hand in hand with a decrease of informal entrepreneurship (in agriculture) and an increase in formal entrepreneurship (in manufacturing):

The expected sign of Per capita income in low-income countries is positive for formal entrepreneurship but negative for informal entrepreneurship.

In high-income economies, there is more opportunity for (innovative) entrepreneurship due to an increased demand for a variety of products and services delivered by innovative start-ups occupying various niche markets (Wennekers et al., 2010). Moreover, entrepreneurship—through its autonomy at work—may contribute to satisfying ‘higher’, non-monetary, needs (Scott Morton & Podolny, 2002). In high-income economies, small-scale, high-tech enterprises can begin as an incorporated business anticipating firm growth (Levine & Rubinstein, 2017). Others may start as unincorporated businesses to obtain higher work autonomy.Footnote 11

The expected sign of Per capita income in high-income countries is positive for both formal and informal entrepreneurship.

Group (iii): government policies that influence the scale and nature of entrepreneurship but where this is not the main objective of policy

This section identifies four government policy areas that prior work has shown influence the scale and type of entrepreneurship. Some have a positive, and others a negative, effect on entrepreneurship, but their common characteristic is that the enhancing of entrepreneurship is not their prime focus. It is therefore more difficult for entrepreneurship policy-makers to influence their scale and delivery.

-

Education policies

Education budgets take account of a wide range of social and economic factors, but considerations of their impact on entrepreneurship is usually minimal. This is despite evidence that the scale and nature of educated individuals in a country influences entrepreneurship (Van der Sluis et al., 2008).

There are two main reasons why education levels in a country are correlated both with enterprise creation rates and with a high proportion of these enterprises being formal. The first is that the management, particularly of a successful business, requires considerable intellectual skills and is therefore more likely to be restricted to those having these skills. Formal education may be seen as a proxy for such skills. The second is that the establishment of a, potentially, high-growth technology business is likely to be restricted to those with the highest levels of education. Such businesses, although they may start in a garage or in a front-room will, if they succeed, require external resources normally only available on a sufficient scale to a formal enterprise.

There are however also reasons why education levels might be either negatively or uncorrelated with business creation rates. For example, several high-profile entrepreneurs—Gates, Zuckerberg—either never went to, or never completed, college and it is suggested this gave them the motivation to start and grow their enterprise. Their shortage of capital was addressed by beginning informally—what Winborg and Landstrom (2001) refer to as bootstrapping.

Parker (2018) reviews these relationships and concludes that the bulk—but certainly not all—studies in high-income countries find that start-up, survival and growth rates are higher when the founders have higher (tertiary) education. However, in low-income countries, (tertiary) educated individuals were more likely to enter low-risk government or professional employment rather than establish higher risk business creation (Van der Sluis et al., 2008).

Our measure of education is the share of the labour force holding secondary educational qualifications. In high-income countries, this has to be benchmarked against tertiary education. In low-income countries, where tertiary education is much less common, this has to be benchmarked against primary education.

The expected sign of Secondary Education in high-income countries is negative for formal entrepreneurship and indeterminate for informal entrepreneurship.

The expected sign of Secondary Education in low-income countries is positive for formal entrepreneurship and indeterminate for informal entrepreneurship.

-

Policies to promote Foreign Direct Investment

A second policy open to governments is to seek to raise rates of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), primarily on the grounds that large externally owned companies are able to directly provide employment. Nevertheless, a secondary consideration is whether this, in turn, raises supply chain opportunities for indigenous and normally small-scale enterprises (Nell et al., 2011). The evidence for this is clearer in high-income countries where De Clercq et al. (2008) and Lee et al. (2014) find FDI has positive spillover effects on the local economy.

In low-income countries, these positive effects may be offset by crowding-out effects because local, primarily informal, firms then experience competition from foreign firms (De Backer & Sleuwaegen, 2003). This is because multinational enterprises, attracted by such policies, place a premium on quality and reliability from local suppliers, so stimulating primarily formal, rather than informal, domestic enterprises.

The expected sign of FDI in high-income countries is positive for both formal and informal entrepreneurship.

In low-income countries the expected sign of FDI is positive for formal entrepreneurship but indeterminate for informal entrepreneurship.

-

Policies influencing the scale and nature of Government Consumption

The tax regime in a country reflects a wide range of both social and economic choices. Some countries may seek to make themselves ‘enterprise attractive’ by having policies that focus on lowering all forms of taxes and so leading to ‘small government’. Others place more emphasis on achieving social objectives which are likely to be delivered by public organisations paid for from general taxation (Nyström, 2008).

Once again, the evidence that these decisions have on the scale and nature of entrepreneurship in an economy is mixed. Those pointing towards a positive link—particularly in high-income countries—emphasise the role of public infrastructure in providing an environment in which businesses can trade. Clear modern examples are the provision of technological infrastructure (Woolley, 2014) but more mundane examples are crime-reduction initiatives that enable (small) businesses to prosper (Drinkwater et al., 2018).

The contrasting argument is that, because such expenditure is normally funded through higher taxes, this depresses entrepreneurial activity (Henrekson & Sanandaji, 2011), although its impact depends on the type of tax [profits tax; income tax; inheritance tax] and on the scale and nature of enforcement.

The effect of small government (i.e. lower taxes) on the ratio of formal to informal entrepreneurship is also unclear; it could encourage more formal entrepreneurship because the tax advantages of being informal are reduced. Alternatively, it may encourage more individuals to start a business, perhaps initially informally, because they are able to legally retain a higher proportion of their profits and use them for expansion.

All in all, the evidence (Bosma et al., 2018; Henrekson & Sanandaji, 2011) points to ‘big government’ being funded from higher tax rates, so making formal entrepreneurial activity less attractive. Its impact on informal entrepreneurship is less clear:

The expected sign of Government Consumption—our measure of government size — on formal entrepreneurship is negative, in both high- and low-income countries.

The expected sign of Government Consumption on informal entrepreneurship is indeterminate, in both high- and low-income countries.

-

Policies to increase female activity rates

Ardichvili et al. (2003) argued that the key factor influencing the take-up of entrepreneurship was the ability of individuals to identify business opportunities, and that such opportunities were more apparent to those with current labour market experience. A second influence is that of firm size: Johnson and Cathcart, as long ago as 1979, showed business founders were five times more likely to have worked in a small, rather than a larger firm immediately prior to starting their enterprise.

Government can alter economic activity and enterprise rates, particularly for females, but this is difficult in some countries because of strongly-held religious beliefs. OECD (2013), for example, made the case that the low rates of female labour force participation in the Middle-East and North African (MENA) countries was a key factor underpinning low enterprise rates in these countries.Footnote 12 A second effect of these low participation rates is that females starting such businesses may be more uncertain about their likelihood of success than males (e.g. by a lack of successful female role models). On those grounds, the business is more likely to be of a smaller scale and be informal rather than formal (Oppedal Berge & Garcia Pires, 2020).

By contrast, in (low-income) countries with relatively high female labour force participation rates, there are more women with current labour market experience who are potentially able to identify promising business opportunities and start a business. Moreover, the higher (female) labour supply in these countries makes it easier for all firms (whether male-led or female-led) to find qualified employees, thereby making it easier to run an employer firm. These examples of opportunity-based entrepreneurship are expected to be more characteristic of the formal, rather than the informal, sector.

In high-income countries female activity rates are considerably higher than in low-income countries but, when asked about entrepreneurship, many women claim to favour starting businesses in the informal sector because this enables them to optimally combine work and family (Verheul, 2005). A second factor is that, in high-income countries, females are disproportionately more likely to be employed in the public sector which generally provides a family-friendly environment, so lowering their likelihood of engaging in (formal) entrepreneurship where the hours worked are considerably longer and less predictable (Hopp & Martin, 2017).

The expected sign of Female labour force participation in low-income countries is positive for formal entrepreneurship and indeterminate for informal entrepreneurship.

The expected sign of Female labour force participation in high-income countries is indeterminate for formal entrepreneurship and positive for informal entrepreneurship.

Group (iv): controls

-

Finally, we identify the role played by two key controls—GDP growth and unemployment—which have been shown to influence the scale and composition of enterprise rates.

-

GDP growth

Macro-economic conditions are theorised to influence types of entrepreneurship differently. In prosperous conditions (i.e. high GDP growth), it is argued that those starting a new business are more likely to be influenced by good market prospects—they are ‘pulled’ into entrepreneurship (Sedláček & Sterk, 2017). In contrast, in recessions (i.e. low or negative GDP growth), entrants are more likely to be ‘pushed’ into entrepreneurship by the lack of employment opportunities (Brünjes & Revilla Diez, 2013). Those that are pulled are more likely to begin formally since, as noted earlier, this decision reflects their optimism about the growth of the business, whereas those that are pushed are likely to have more modest aspirations and skills.

The expected sign of GDP growth is positive for formal entrepreneurship and negative for informal entrepreneurship, for both high- and low-income countries.

-

Unemployment

High unemployment rates may be positively associated with entrepreneurship when unemployed individuals are motivated to start their own business by a lack of employment options (‘recession-push’-effect). However, if high unemployment signals low aggregate demand, then this may lower the likelihood of a start-up being successful (‘prosperity-pull’-effect) (Storey, 1991; Thurik et al., 2008).

More widely, the link between macro-economic conditions, unemployment and business creation in high-income countries points to different roles for formal and informal entrepreneurship. It suggests the unemployed are more likely to enter informal entrepreneurship, in line with the positive association between unemployment rates and rates of informal entrepreneurship. As a counter-argument, entrepreneurs aiming to start a small (informal) business, may be waiting for the right moment to start up, i.e. when aggregate demand is high (and unemployment is low), according to the prosperity-pull effect.

Evidence for low-income countries is sparse but Brünjes and Revilla Diez (2013) conclude that, when employment opportunities improved, entrepreneurs were more likely to state they started their business for positive reasons.

All in all, it is difficult to predict whether ‘recession-push’ or ‘prosperity-pull’ effects dominate:

The expected sign of Unemployment is indeterminate from theory, for both formal and informal entrepreneurship, and both high- and low-income countries.

3 Our approach to testing

Online Appendix Table A1 sets out, in full, all variables used in the analysis. Column 1 shows the name and definition of each dependent and independent variable. Column 2 describes the variable and column 3 specifies the data source used. The table also shows the expected signs of each of the twelve (potential) determinants discussed in Section 2, for each of four contexts per determinant (high-income versus low-income crossed with formal versus informal entrepreneurship).

For the two dependent variables, the fourth column shows the prior studies that were drawn upon in the literature review in Section 2. This is also provided for the independent variables, together with their expected relationship with the dependent variables, as theorised in Section 2.

We now supplement Online Appendix Table A1 by providing a more detailed description of the dependent variables that capture formal and informal entrepreneurship.

3.1 Formal entrepreneurship

Acs et al. (2008) argued that formal entrepreneurship was best captured by the normalised number of Limited Liability Companies (LLCs) on the grounds that such enterprises have incurred the cost and time to formally register with a State agency. The case for LLCs—also labelled incorporated businesses—is supported by evidence from Levine and Rubinstein (2017). They show only a small proportion of unincorporated businesses make the transition to incorporation, suggesting that the choice of the business’s legal form largely reflects the ex-ante views of the business owner(s), not its ex-post performance. They also argue that the choice of legal form reflects the realistic aspirations of its owner(s) because the incorporated self-employed earn more than comparable salaried workers, whereas the unincorporated self-employed earn much less.

We follow Acs et al. (2008) and take, as our measure of formal entrepreneurship, the rate of new limited liability companies (LLCs) per adult population as measured by the World Bank Group Entrepreneurship Survey (WBGES) (Klapper et al., 2010).

3.2 Informal entrepreneurship

Four benchmark studies have measured the nature and scale of informal entrepreneurship: Acs et al. (2008), Thai and Turkina (2014), Dau and Cuervo-Cazurra (2014) and Autio and Fu (2015). Each used different approaches, but all took the number of young business entrepreneurs according to Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) as a measure of ‘total’ entrepreneurship and then subtracted the number of new LLCs according to WBGES (as measure of formal entrepreneurship).

As straightforward as this may sound, in reality it is a cumbersome operation because three corrections are made in some, but not in all, studies. The first correction takes into account that the number of new LLCs relates to new businesses registered in the last year, whereas GEM’s young business entrepreneurship rate relates to the number of new entrepreneurs in the last 42 months (Bosma, 2013).Footnote 13 Second, while making this correction, some authors (Acs et al., 2008; Autio & Fu, 2015) recognise that survival rates increase over time; hence, the assumption of a simple linear distribution of new entrepreneurs over the 42 months is questionable. Third, firms may have several business owners and so a correction for average team size is in order (Autio & Fu, 2015; Dau & Cuervo-Cazurra, 2014).

As a result of the corrections, the scale of informal entrepreneurship reported in the studies varies considerably. These differences relate not only to the absolute numbers but also to the relative prevalence of formal versus informal entrepreneurship in different studies.

Of the corrections, only Autio and Fu (2015) apply all three but, even here, issues of non-comparability remain because, as noted, GEM uses information from individuals whereas World Bank measures are based upon information from businesses. Ahmad (2008) and Cieślik (2015) both note the many sources of incomparability between statistical business registers and population surveys—most notably variations in team-size. Finally, shell companies—incorporated businesses registered for tax or other non-business purposes (Acs et al., 2008; Klapper et al., 2010) but which cannot be linked to active entrepreneurs—are a further problem in comparing the World Bank measure of the number of new LLCs with the GEM measure of the number of entrepreneurs.

For all these reasons, this paper explicitly avoids constructing a measure of informal entrepreneurship that combines measures from two different data sources. Even when these calculations are quite sophisticated, our view is that a considerable degree of arbitrariness remains.

Our measure of Informal Entrepreneurship, ranging from unregistered enterprises to unincorporated enterprises (Chen, 2012) is the young business entrepreneurship (YB) rate as measured by GEM. The YB rate is defined as the number of owner-managers of businesses between 3 and 42 months old, per adult population (Bosma, 2013).

In summary, our measures of formal and informal entrepreneurship are taken from separate sources. Although not perfectly comparable with each other, they have the merit of being comparable across countries, so facilitating a cross-country investigation of the determinants of formal and informal entrepreneurship.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 1 provides the key descriptive statistics.Footnote 14

Even after recognising that the ratio of informal entrepreneurship to formal entrepreneurship is likely to have been an overestimate,Footnote 15 it is clear that informal entrepreneurial activity rates (number of individuals running a young business) are substantially higher than formal entrepreneurship rates (number of new LLCs in a given year).

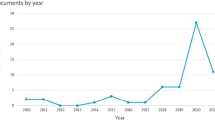

The ratio of formal to informal entrepreneurship rates is shown graphically in Fig. 1. It ranks all 58 countries for which both measures are available by GDP per capita, varying from the lowest (India) on the left to the highest (United Arab Emirates) on the right. It shows formal entrepreneurship is minimal in the lowest-income countries, but clearly rises as GDP per head rises. This relationship is, however, not fully consistent, with, for example, low-income South Africa having a higher proportion of formal entrepreneurship than high-income Austria or Canada.

Table 2 shows the correlation between formal and informal entrepreneurship is negligible, suggesting that the two forms capture very different aspects of entrepreneurship. The table also shows the independent variables correlated with formal entrepreneurship differ markedly from those correlated with informal entrepreneurship. We now explore these differences in more detail.

4.2 Determinants of formal and informal entrepreneurship in high- and low-income countries

Table 3 takes one measure of entrepreneurship capturing informality and one capturing formality. It examines the role of twelve factors—placed in four groups—theorised to influence each metric. The first two columns present the results for all countries; the second two columns show the results for low-income countries and the final two columns show results for high-income countries. Both measures of entrepreneurship are expressed in natural logarithms to enable the coefficients to be directly comparable across the columns.

Our data set is an unbalanced panel of 441 observations distributed across 81 countries for formal entrepreneurship and 319 observations across 72 countries for informal entrepreneurship, and spanning the period 2004–2014. As we are focusing on explaining cross-country differences while also exploiting variations over time, the estimation methods we consider are random effects and pooled OLS (but not fixed effects). Breusch-Pagan tests indicated that for all six models random effects was the preferred estimation method.Footnote 16 We also tested for multicollinearity for which we did not find any indications.Footnote 17

In our random effects estimations, we cluster standard errors by country in order to avoid underestimation of standard errors (and of associated p-values that determine coefficients’ significance levels). Nevertheless, as a robustness test, in Online Appendix Table A3, we also report results from between-estimator regressions, where, for each country, all model variables are averaged over the years for which data were available for the country in question. The number of observations in these between-estimator regressions thus equals the number of countries, making the ratio of number of observations over number of independent variables relatively low. Notwithstanding, in our discussion of regression results below, we will take a conservative approach, and only consider results from our main Table 3 to be significant if they are robust to applying the between-estimator. Although not all our significant results ‘survive’ this robustness test, most of them do, and overall we judge our main results to be solid, considering the stringent nature of this robustness test.Footnote 18 Since the between-estimator considers pure cross-country variations, cyclical variables like GDP growth and unemployment (i.e. our Group (iv) control variables) have been removed from the regression models reported in Online Appendix Table A3.

Group (i) variables

The ease of starting a business DTF_Starting is positively associated with the rate of formal entrepreneurship but not, or only weakly, with informal entrepreneurship. This result is in line with our theorising. The WGI index is also positively related with formal entrepreneurship but not with informal entrepreneurship, again confirming our expectations. However, only for low-income countries is this result established beyond any doubt (see Online Appendix Table A3). Further exploration revealed that the positive relation between the overall WGI index and the rate of formal entrepreneurship for low-income countries primarily reflects the importance of political stability.Footnote 19

For self-employment, the sign is positive for informal entrepreneurship in low-income countries but not in high-income countries. For formal entrepreneurship, we do not find any statistically significant positive association with self-employment. Hence, for low-income countries, we find evidence for the role-model hypothesis (Bosma et al., 2012) where higher rates of (informal) self-employment induce even more entrepreneurial activity in the informal sector. However, our results do not support the stepping stone hypothesis where informal self-employment leads to higher entry rates in formal entrepreneurship (Bennett, 2010). In high-income countries we see no link with either formal or informal entrepreneurship.

Group (ii) variables

Our results for Share agriculture in low-income countries in Table 3 are broadly in line with our theorised signs, although no longer significant in the robustness test (see Online Appendix Table A3). The non-significant signs for high-income countries possibly reflect the low entry rates in farming. Although we expected Share services to have a positive sign, it was non-significant, possibly reflecting our broad definition of Services. Results for per capita income—our measure of economic development—also do not match our expectations, perhaps because several manifestations of economic development, such as sector structure and the WGI Index, are also included in the model. Reassuringly though, the direct correlations between per capita income and formal and informal entrepreneurship (positive and negative, respectively) are in line with our expectations (see Table 2).

Group (iii) variables

Our results for Secondary education are non-significant except for formal entrepreneurship in low-income countries, the latter finding being as expected, but not confirmed in the robustness test. Results for FDI are also non-significant, perhaps indicating that spillover and crowding-out effects cancel each other out.Footnote 20 In high-income countries, Government consumption is clearly negatively related with formal entrepreneurship rates, in line with our ‘big government’ argument. However, this result is not confirmed in the robustness test.

Results for Female labour force participation are in line with our theorising. Higher economic participation rates by women is strongly associated with more formal entrepreneurship in low-income countries and weakly associated with informal entrepreneurship in high-income countries. This result is robust to applying the between-estimator (see Online Appendix Table A3).

Group (iv) variables

GDP growth is positively related with formal entrepreneurship, in line with our theorising, whereas the link with informal entrepreneurship is non-significant. Finally, somewhat surprisingly, Unemployment is negatively related to informal entrepreneurship in high-income countries, perhaps implying that individuals or groups do wait for the right moment to start up (‘prosperity-pull’).

5 Interpretations and conclusions

This paper has examined formal and informal entrepreneurial activity across 81 countries over the period from 2004 to 2014. These were very different forms of entrepreneurship; their scale and importance differs considerably across countries and very different factors explain their prevalence. There remain marked differences between high- and low-income countries.Footnote 21

We now set out our view of the implications of these findings for scholars and policy-makers. For scholars, our work confirms that the distinction previously made between formal and informal entrepreneurship is a valid one. We show, for example, that higher self-employment rates—which largely capture (incumbent) informal entrepreneurship—are not related to higher new formal entrepreneurship rates, the type of entrepreneurship usually associated with economic growth and job creation (Astebro & Tåg, 2015; Autio et al., 2019). We believe this reflects a lack of growth potential among informal businesses and is in line with the findings of La Porta and Shleifer (2014, p. 124) who concluded that ‘informal firms stay permanently informal, are unproductive and are unlikely to benefit much from becoming formal’.

The successful firms that start unregistered appear to be the exception rather than the rule, leading to questions over the desirability of a simple ‘scaling-up’ of informal entrepreneurship, particularly in low-income countries, in the expectation it will enhance economic development. In contrast, self-employment rates appear to have positive statistical associations with new informal entrepreneurship, although only in low-income countries, possibly reflecting entrepreneurial role-model effects. For these reasons, Bennett (2010) ‘stepping-stone’ theory is unsupported by our findings.

The differences between high- and low-income countries are also illustrated by the diverse roles played by female labour force participation. This has a positive relationship with formal entrepreneurship in low-income countries, whereas in high-income countries the link is with informal entrepreneurship.

Despite the clarity of these findings, scholars need to seek to both improve data and refine definitions. We have followed others in regarding GEM-based metrics as either the best measure, or a crucial component, of informal entrepreneurship. However, this dataset is based on cross-section samples of self-report data with considerably lower reliability than, for example, company registrations which measure formal entrepreneurship. A minimum requirement for GEM measures to become comparable in terms of reliability to official registrations, and so fully capture informal entrepreneurship, is for it to become panel-based.

However, the biggest challenge for scholars is to acknowledge, and explicitly respond to, the issues that face entrepreneurship policy-makers. Understandably, policy-makers find it difficult to interpret research that explains entrepreneurship outcomes by clusters of variables (e.g. Stenholm et al., 2013; Thai & Turkina, 2014) because of the dilemma of choosing which variables, or which combinations, have to be the focus of their attention. Admittedly, our WGI (governance) index included in Table 3 also suffers from this shortcoming as it is an average of six sub-indices.Footnote 22 As reported earlier, further exploration revealed that the positive impact of governance on formal entrepreneurship for low-income countries (our more robust finding regarding WGI), primarily reflects the importance of political stability. A second example is the inclusion of culture-based variables which, although frequently shown to be associated with entrepreneurship (Minola et al., 2016), say little about the direction of causation. Third, the time-scale of policy-makers has to be recognised by scholars in this area. All else equal, policy makers favour policies that are expected to have an impact over an electoral cycle, rather than over decades (Fotopoulos & Storey, 2017; Fritsch & Wyrwich, 2014) or even longer.

Finally, a distinction is drawn between two groups of public policies that influence the scale and nature of entrepreneurship. The first are those over which entrepreneurship policy-makers have a direct influence on their scale and delivery. The second are public policies that have an equal, or even greater, impact on entrepreneurship, but where entrepreneurship policy-makers exert little influence. Our expectation is that entrepreneurship policy-makers will favour areas where they can exert influence, but this risks inefficiencies in delivery.

In recognition of these issues, we have tried to ensure our findings have a more interpretable policy focus. Expressed most baldly, our message to policy-makers is that entrepreneurship is not a homogeneous commodity, increases in which automatically improve economic welfare in all countries and in all situations. Instead, policy-makers have to select the measure of entrepreneurship they consider appropriate for their country—formal or informal—and then identify the policies, or combinations of policies, appropriate to achieving that aim.

We have tried to assist them by acknowledging that, even when policy areas are shown to exert similar statistically significant influences on entrepreneurship, they are not necessarily equally attractive options to policy-makers. By placing policies into three groups, and identifying influential constraints, we acknowledge the reality of entrepreneurship policy-making. It favours policies over which entrepreneurship policy-makers have control and where impact is expected in the short to medium terms. It leads us to conclude, for example, that, for policy-makers in high-income countries seeking to raise formal entrepreneurship, making it easier to start a business and improving governance are more attractive options (as ‘Group (i)’ variables) than seeking to reduce the ‘size’ of government (as a ‘Group (iii)’ variable), even though all three variables were found to be significantly related to formal entrepreneurship in Table 3. This is because decisions on Group (i) variables are more strongly influenced by entrepreneurship considerations.

In contrast, policy-makers in low-income countries seeking to raise formal entrepreneurship rates also need to make it easier to start businesses and improve governance, but to combine this with policies to raise female activity rates and the level of education, even if, as Group (iii) variables, raising entrepreneurship rates is not the main objective of such policies. If their objective is to raise informal entrepreneurship, we show their most powerful policy is the promotion of self-employment, but this has to acknowledge that our stepping stone result (even though applied at the macro level) implies that this may lead to fewer formal businesses.

We conclude by reflecting upon the observations of an anonymous referee who pointed out to us that our proposal was the reverse of much current practice, where the emerging business economic structure has been the dominant influence on the development of government entrepreneurship and SME policies and programmes. However, our view is that this approach of ‘trial and error’ and following ‘fashionable fads’ is now widely recognised—within some of the academic community at least—as being, at best, wasteful. Even former policy-makers, freed from their responsibilities, acknowledge the limitations of the entrepreneurship policy roller-coaster approach which, in some countries, has characterised policies over long periods of time (Irwin & Scott, 2021).

The evidence provided in this paper encourages policy-makers to begin by carefully reviewing the type of entrepreneurship they seek, and then realistically linking this to the policy instruments at their disposal. In this sense, current causality is indeed reversed. This is because our contribution is not only to emphasise that ‘one size doesn’t fit all’, but then to set out the key choices open to policy-makers. These are between formal and informal entrepreneurship, between macro and micro-instruments, and between those likely to influence outcomes in the medium and longer term. Crucially, it recognises that the entrepreneurship policy of a government is, only one, foci of a democratically elected government.

The challenge for researchers is to robustly, and then continuously, review the factors influencing formal and informal entrepreneurship. To do this, they must become more aware of the nature of the policy environment in which these public policy decisions are made. We see real merit in future research focussing on using individual-level data to investigate some of the relationships examined in this paper and how this changes in response to policy delivery.

Change history

15 August 2022

Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note.

Notes

Urbano et al. (2019).

We recognise others have also distinguished between types of entrepreneurship. Examples include entrepreneurship quality and quantity (Chowdhury et al., 2019; Szerb et al., 2019), Schumpeterian and non-Schumpeterian entrepreneurship (Dilli et al., 2018) or private sector and social entrepreneurship (Bridge et al., 2014).

Our approach is closest to that of Chowdhury et al. (2019), although they distinguish between quantity and quality of entrepreneurship, rather than informal and formal entrepreneurship. Their quantity measure is identical to our informal measure, but their measure of entrepreneurship quality is completely different from the measures used in this paper. They also focus on institutional determinants, whereas we use a broader range of determinants.

High-income—formal entrepreneurship; high-income—informal entrepreneurship; low-income—formal entrepreneurship; low-income—informal entrepreneurship.

Naturally, given the number of empirical relationships to be investigated (i.e. 48), we do not have the space to profoundly derive a formal hypothesis for each of the 48 relationships under investigation. Therefore, we avoid the term ‘hypothesis’ but instead use the term ‘expected sign’ in this paper.

Although the formality/informality choices facing both the business owner and governments are set out independently, they clearly interact. So, for example, the business owner is likely to favour formality in an economy where property rights are more strongly enforced.

In particular, since compliance requirements are far less strict and extensive, operationally, we consider entrepreneurs in unincorporated businesses informal entrepreneurs, in line with Chen (2012). This is not to say that conceptually (in terms of registering a business with the appropriate government agencies), these entrepreneurs are not also formal entrepreneurs. However, since both the costs and benefits of the LLC legal form are greater compared to unincorporated businesses, operationally we limit formal entrepreneurship to LLCs, following the convention in the small field of literature dealing with formal versus informal entrepreneurship (Acs et al., 2008; Autio and Fu, 2015; Dau and Cuervo-Cazurra, 2014; Thai and Turkina, 2014).

An anonymous referee pointed out to us that, in some countries, formality can ensure enhanced access to the legal system which could be of value in dispute resolution.

Williams et al. (2017) make the case that, in low-income countries, the apprenticeship role for informality is beneficial. They show those businesses that are currently formal, but began informally, have higher survival rates than those that began formally. However, not all informal businesses were tracked from inception, in particular those that never switched to formality.

DTF stands for ‘Distance to Frontier’. See Online Appendix Table A1 (available online separately).

Only 32% of women of working age in MENA countries participate in the labour force, compared with 56% in low- and middle-income countries and over 61% in OECD countries (OECD 2013, pp. 14–15).

The new business density measure capturing formal entrepreneurship divides the original World Bank measure by 10. This enables formal and informal entrepreneurial activity to be expressed as a percentage of the working age population, and so become more validly comparable.

In particular, factors contributing to an overestimation of the number of informal entrepreneurs relative to formal entrepreneurs are (1) the measurement period of 42 months for young business owners relative to one calendar year for new LLCs and (2) the phenomenon of multiple owners per business. The main factor working in the opposite direction is the inclusion of shell companies in the formal entrepreneurship measure. Overall, we consider it likely that the combination of these factors overestimate the number of informal entrepreneurs (relative to formal ones) but we consider it unlikely that such overestimation would explain a gap of a factor 9 (4.07 versus 0.44) as reported in Table 1.

Test statistics available on request.

The mean variance inflation factors (VIF) for the full, low-income and high-income country samples are 2.99, 7.18 and 2.69, respectively. As these VIF’s are less than the value of 10, multicollinearity is not a cause for concern in the analysis.

Note that in some models in Online Appendix Table A3, there are just 36 observations for 10 independent variables, making it hardly feasible, technically, for the estimation algorithm to find multiple significant coefficients.

More details can be found at the end of the Online Appendix.

In the robustness test results in Appendix Table A3 (available online separately), we find a highly significant positive coefficient in model (1), in line with our theorising.

We are aware that countries may be classified on the basis of broader considerations than income or the standard of living alone. For instance, in the United Nations’ Human Development Index (HDI), the standard of living is just one out of three basic components comprising the HDI index (the other two being life expectancy and years of schooling; UNDP, 2020). Future research may consider using the four Human development groups of countries as reported in the United Nations’ Human Development Reports: Low, Medium, High and Very high Human development (UNDP, 2020).

We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

References

Acs, Z. J., Desai, S., & Klapper, L. F. (2008). What does “entrepreneurship” data really show? Small Business Economics, 31(3), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9137-7

Ahmad, N. (2008). A proposed framework for business demography statistics. In: E. Congregado (Ed.), Measuring Entrepreneurship Building a Statistical System (pp. 113–174). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-72288-7_7.

Aidis, R., Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. M. (2012). Size matters: Entrepreneurial entry and government. Small Business Economics, 39(1), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9299-y

Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., & Ray, S. (2003). A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00068-4

Astebro, T. B., & Tåg, J. (2015). Entrepreneurship and job creation. IFN Working Paper No. 1059. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2576044. Stockholm: Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN).

Autio, E., & Fu, K. (2015). Economic and political institutions and entry into formal and informal entrepreneurship. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32(1), 67–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-014-9381-0

Autio, E., Pathak, S., & Wennberg, K. (2013). Consequences of cultural practices for entrepreneurial behaviours. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(4), 334–362. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2013.15

Autio, E., Fu, K., & Levie, J. (2019). Entrepreneurship as a driver of innovation in the digital age. Background paper to the report “Asian Development Outlook 2020: What Drives Innovation in Asia?” prepared for the Asian Development Bank.

Bannerji, A., & Jain, S. (2007). Quality dualism. Journal of Development Economics, 84(1), 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.09.010

Baumol, W. J. (1990). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98, 893–921. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)00014-X

Bennett, J. (2010). Informal firms in developing countries: Entrepreneurial stepping stone or consolation prize? Small Business Economics, 34(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9194-6

Bosma, N. (2013). The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) and its impact on entrepreneurship research. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 9(2), 143–248. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000033

Bosma, N., Hessels, J., Schutjens, V., Van Praag, M., & Verheul, I. (2012). Entrepreneurship and role models. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(2), 410–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.03.004

Bosma, N., Content, J., Sanders, M., & Stam, E. (2018). Institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth in Europe. Small Business Economics, 51(2), 483–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0012-x

Bowen, H. P., & De Clercq, D. (2008). Institutional context and the allocation of entrepreneurial effort. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(4), 747–767. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400343

Bridge, S., Murtagh, B., & O’Neill, K. (2014). Understanding the Social Economy and the Third Sector (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-08714-0

Brünjes, J., & Revilla Diez, J. (2013). ‘Recession push’ and ‘prosperity pull’ entrepreneurship in a rural developing context. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(3–4), 251–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2012.710267

Capelleras, J. L., Mole, K. F., Greene, F. J., & Storey, D. J. (2008). Do more heavily regulated economies have poorer performing new ventures? Evidence from Britain and Spain. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(4), 688–704. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400340

Carree, M.A., & Thurik, A.R. (2010). The impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth. In Z. J. Acs, & D. B. Audretsch (Eds.), Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research, 2nd Edition (pp. 557–594). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1191-9_20.

Chen, M. A. (2012). The informal economy: Definitions, theories and policies. WIEGO Working Paper No 1. WIEGO.

Chenery, H. B. (1960). Patterns of industrial growth. American Economic Review, 50(4), 624–654.

Chowdhury, F., Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2019). Institutions and entrepreneurship quality. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(1), 51–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718780431

Cieślik, J. (2015). Capturing statistically the “Intermediate Zone” between the employee and employer firm owner. International Review of Entrepreneurship 13(3), 205–214. https://www.senatehall.com/entrepreneurship?article=519.

Coad, A., Frankish, J. S., Roberts, R. G., & Storey, D. J. (2016). Predicting new venture survival and growth: When does the fog lift? Small Business Economics, 47, 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9713-1

Dau, L. A., & Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2014). To formalize or not to formalize: Entrepreneurship and pro-market institutions. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(5), 668–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.05.002

De Backer, K., & Sleuwaegen, L. (2003). Does foreign direct investment crowd out domestic entrepreneurship? Review of Industrial Organization, 22(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022180317898

De Clercq, D., Hessels, J., & Van Stel, A. (2008). Knowledge spillovers and new ventures’ export orientation. Small Business Economics, 31(3), 283–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9132-z

De Jong, A., Rietveld, C. A., & Van Stel, A. (2020). The relationship between entry regulation and nascent entrepreneurship revisited. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 18(3), 419–446. https://www.senatehall.com/entrepreneurship?article=664.

Dilli, S., Elert, N., & Herrmann, A. M. (2018). Varieties of entrepreneurship: Exploring the institutional foundations of different entrepreneurship types through ‘Varieties-of-Capitalism’ arguments. Small Business Economics, 51(2), 293–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0002-z

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2002). The regulation of entry. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355302753399436

Drinkwater, S., Lashley, J., & Robinson, C. (2018). Barriers to enterprise development in the Caribbean. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 30(9–10), 942–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2018.1515821

Fain, T. S. (1980). Self-employed Americans: Their number has increased. Monthly Labor Review, 103(11), 3–8.

Fainshmidt, S., Judge, W. Q., Aguilera, R. V., & Smith, A. (2018). Varieties of institutional systems: A contextual taxonomy of understudied countries. Journal of World Business, 53(3), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2016.05.003

Fotopoulos, G., & Storey, D. J. (2017). Persistence and change in inter-regional differences in entrepreneurship 1921–2011. Environment and Planning A, 49(3), 670–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16674336

Frankish, J., Roberts, R., Coad, A., Spears, T., & Storey, D. J. (2013). Do entrepreneurs really learn or do they just tell us that they do? Industrial and Corporate Change, 22(1), 73–106. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dts016

Freedman, J., & Godwin, M. (1994). Incorporating the micro business: Perceptions and misperceptions. In A. Hughes & D. J. Storey (Eds.), Finance and the Small Firm (pp. 232–283). Routledge.

Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2014). The long persistence of regional levels of entrepreneurship: Germany, 1925–2005. Regional Studies, 48(6), 955–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.816414

Giugale, M. M., El-Diwany, S., & Everhart, S. S. (2000). Informality, size and regulation: Theory and an application to Egypt. Small Business Economics, 14(2), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008164103537

Henrekson, M., & Sanandaji, T. (2011). Entrepreneurship and the theory of taxation. Small Business Economics, 37(2), 167–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9242-2

Hopp, C., & Martin, J. (2017). Does entrepreneurship pay for women and immigrants? A 30 year assessment of the socio-economic impact of entrepreneurial activity in Germany. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 29(5–6), 517–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1299224

ILO. (2019). Small matters: Global evidence on the contribution to employment by the self-employed, micro-enterprises and SMEs. International Labour Organization. http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/522091.

Irwin, D., & Scott, J. M. (2021). Five decades of small business policy in England: Policy as a value proposition or window dressing?. British Politics, forthcoming. Online first 25 May 2021. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-021-00179-3.

Johnson, P. S., & Cathcart, D. G. (1979). The founders of new manufacturing firms: A note on the size of their ‘incubator’ plants. Journal of Industrial Economics, 28(2), 219–224. https://doi.org/10.2307/2098039

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2011). The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, 3(2), 220–246. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1876404511200046

Klapper, L., Amit, R., & Guillén, M.F. (2010). Entrepreneurship and firm formation across countries. In: J. Lerner, & A. Schoar (Eds.), International Differences in Entrepreneurship (pp. 129–158). University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226473109.003.0005.

La Porta, R., & Shleifer, A. (2014). Informality and development. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.28.3.109

Lee, H., Hong, E., & Sun, L. (2014). Inward foreign direct investment and domestic entrepreneurship: A regional analysis of regional firm creation in Korea. Regional Studies, 48(5), 910–922. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.690067

Levie, J., & Autio, E. (2011). Regulatory burden, rule of law, and entry of strategic entrepreneurs: An international panel study. Journal of Management Studies, 48(6), 1392–1419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.01006.x

Levine, R., & Rubinstein, Y. (2017). Smart and illicit: Who becomes an entrepreneur and do they earn more? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(2), 963–1018. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw044

Millán, J. M., Congregado, E., Román, C., Van Praag, M., & Van Stel, A. (2014). The value of an educated population for an individual’s entrepreneurship success. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(5), 612–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.09.003

Minola, T., Criaco, G., & Obschonka, M. (2016). Age, culture, and self-employment motivation. Small Business Economics, 46(2), 187–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9685-6

Nell, P. C., Ambos, B., & Schlegelmilch, B. B. (2011). The MNC as an externally embedded organization: An investigation of embeddedness overlap in local subsidiary networks. Journal of World Business, 46(4), 497–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2010.10.010

Ngobo, P. V., & Fouda, M. (2012). Is ‘Good’ governance good for business? A cross-national analysis of firms in African countries. Journal of World Business, 47(3), 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2011.05.010

Nyström, K. (2008). The institutions of economic freedom and entrepreneurship: Evidence from panel data. Public Choice, 136(3–4), 269–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-008-9295-9

OECD. (2013). New Entrepreneurs and High Performance Enterprises in the Middle East and North Africa. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264179196-en

Okamuro, H. & Ikeuchi, K. (2017). Work-life balance and gender differences in self-employment income during the start-up stage in Japan. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 15(1), 107–130. https://www.senatehall.com/entrepreneurship?article=565.

Oppedal Berge, L. I., & Garcia Pires, A. J. (2020). Gender, formality, and entrepreneurial success. Small Business Economics, 55(4), 881–900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00163-8

Parker, S. C. (2018). The Economics of Entrepreneurship (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316756706

Scott Morton, F., & Podolny, J. (2002). Love or money? The effects of owner motivation in the California wine industry. Journal of Industrial Economics, 50(4), 431–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6451.00185

Sedláček, P., & Sterk, V. (2017). The growth potential of startups over the business cycle. American Economic Review, 107(10), 3182–3210. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20141280

Stenholm, P., Acs, Z. J., & Wuebker, R. (2013). Exploring country-level institutional arrangements on the rate and type of entrepreneurial activity. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(1), 176–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.11.002

Storey, D. J. (1991). The birth of new firms – Does unemployment matter? A review of the evidence. Small Business Economics, 3(3), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00400022

Straub, S. (2005). Informal Sector: The credit market channel. Journal of Development Economics, 78(2), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2004.09.005

Szerb, L., Lafuente, E., Horváth, K., & Páger, B. (2019). The relevance of quantity and quality entrepreneurship for regional performance: The moderating role of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Regional Studies, 53(9), 1308–1320. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1510481

Thai, M. T. T., & Turkina, E. (2014). Macro-level determinants of formal entrepreneurship versus informal entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(4), 490–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.07.005

Thurik, A. R., Carree, M. A., Van Stel, A., & Audretsch, D. B. (2008). Does self-employment reduce unemployment? Journal of Business Venturing, 23(6), 673–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.01.007

Uhlaner, L., & Thurik, R. (2007). Postmaterialism influencing total entrepreneurial activity across nations. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 17(2), 161–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-87910-7_14

UNDP. (2020). Human Development Report 2020: The Next Frontier — Human Development and the Anthropocene. United Nations Development Programme. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2021.1898908

Urbano, D., Aparicio, S., & Audretsch, D. B. (2019). Twenty-five years of research on institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth: What has been learned? Small Business Economics, 53(1), 21–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0038-0

Van der Sluis, J., Van Praag, C., & Vijverberg, W. (2008). Education and entrepreneurship selection and performance: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 22(5), 795–841. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2008.00550.x

Van Stel, A., Storey, D. J., & Thurik, A. R. (2007). The effect of business regulations on nascent and young business entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 28(2–3), 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-9014-1

Verheul, I. (2005). Is there a (Fe) Male Approach? Understanding Gender Differences in Entrepreneurship, PhD thesis, Erasmus University Rotterdam. ERIM. hdl.handle.net/1765/2005.

Verheul, I., Van Stel, A., & Thurik, A. R. (2006). Explaining female and male entrepreneurship at the country level. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 18(2), 151–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620500532053

Virglerova, Z., Dobes, K., & Vojtovic, S. (2016). The perception of the state’s influence on its business environment in the SMEs from Czech Republic. Administratie Si Management Public, 26, 78–96.

Wennekers, S., Van Stel, A., Carree, M., & Thurik, R. (2010). The relationship between entrepreneurship and economic development: Is it U-shaped? Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 6(3), 167–237. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000023

Williams, C. C., Martinez-Perez, A., & Kedir, A. M. (2017). Informal entrepreneurship in developing economies: The impacts of starting up unregistered on firm performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(5), 773–799. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12238

Winborg, J., & Landstrom, H. (2001). Financial bootstrapping in small businesses: Examining small business managers’ resource acquisition behaviors. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(3), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00055-5

Woolley, J. L. (2014). The creation and configuration of infrastructure for entrepreneurship in emerging domains of activity. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(4), 721–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12017

Young, S. L., Welter, C., & Conger, M. (2018). Stability vs. flexibility: The effect of regulatory institutions on opportunity type. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(4), 407–441. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-017-0095-7

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Laing, E., van Stel, A. & Storey, D.J. Formal and informal entrepreneurship: a cross-country policy perspective. Small Bus Econ 59, 807–826 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00548-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00548-8