Abstract

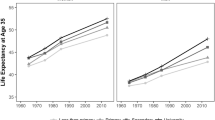

This article analyses the development of inequalities across the lifespan and generations in France using a pseudo-panel developed from successive waves of the French Household Expenditure Survey that took place between 1979 and 2011. The standard of living of individuals, evaluated using individualised disposable income or private consumption, including housing costs, is decomposed by sex and educational attainment. Our Age-Period-Cohort models reveal that men with lower education levels who were born after 1950 experienced a significant decline in disposable income compared to those born between 1918 and 1950. Conversely, we observe no decline in disposable income when the whole population of men is considered. The evolution is rather different for women: those with lower education levels did not experience any decline, whereas the overall population of women benefitted from a strong increase in disposable income across generations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As an illustration, Duru-Bellat and Kieffer (2008) computed that the percentage of access to tertiary education rose from 27.7% for the 1962–1967 cohorts to 53.2% for the 1975–1980 cohorts.

Note that we do not follow the recommendations made by the NTA (United Nations, 2013), which suggest to allocate property incomes to the household head only. Since such an allocation would bias our results by gender, we have chosen a more realistic one.

We exclude people aged under 25 and over 84 as they are less representative of their generation in the BdF survey than intermediary age categories. This is because the proportion of these people living in an institution or other household is greater and numbers in the various databases are lower.

For ease of viewing, we have named each age group after its median. Thus the 45–49 age group is named 47.

References

Afsa-Essafi, C., & Buffeteau, S. (2006). L’activité féminine en France : Quelles évolutions récentes, quelles tendances pour l’avenir ? Economie Et Statistique, 398–399, 85–97.

Alesina, A., Stantcheva, S., & Teso, E. (2018). Intergenerational mobility and preferences for redistribution. American Economic Review, 108(2), 521–554.

Amossé, T., & Chardon, O. (2006). Les travailleurs non qualifiés : Une nouvelle classe sociale ? Économie Et Statistique, 393–394, 203–229.

Arrow, K., Dasgupta, P., Goulder, L., Daily, G., Ehrlich, P., Heal, G., Levin, S., Mäler, K.-G., Schneider, S., Starrett, D., & Walker, B. (2004). Are we consuming too much? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(3), 147–172.

Ben-Halima, B., Chusseau, N., & Hellier, J. (2014). Skill premia, and intergenerational education mobility: The French case. Economics of Education Review, 39, 50–64.

Boppart, T., & Krusell, P. (2016). Labor supply in the past, present, and future: A balanced-growth perspective. NBER Working Paper No. 22215.

Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2015). Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. PNAS, 112(49), 15078–15083.

d’Albis, H., & Badji, I. (2017). Intergenerational inequalities in standards of living in France. Economics and Statistics, 491–492, 71–92.

d’Albis, H., Bonnet, C., Chojnicki, X., El Mekkaoui, N., Greulich, A., Hubert, J., & Navaux, J. (2019). Financing the consumption of young and old in France. Population and Development Review, 45(1), 103–132.

d’Albis, H., Bonnet, C., Navaux, J., Pelletan, J., Toubon, H., & Wolff, F.-C. (2015). The lifecycle deficit for France, 1979–2005. Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 5, 79–85.

d’Albis, H., Bonnet, C., Navaux, J., Pelletan, J., & Wolff, F.-C. (2016). Travail rémunéré et travail domestique : Une évaluation monétaire de la contribution des femmes et des hommes à l’activité économique depuis 30 ans. Revue De l’OFCE, 149, 101–130.

d’Albis, H., & Badji, I. (2019). Intergenerational inequalities in mortality-adjusted disposable income. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 17, 37–69.

d'Albis, H., & Badji, I. (2020). Les inégalités intra-générationnelles en France. PSE working paper N° 2020-14.

Deaton, A. (1985). Panel data from time series of cross-sections. Journal of Econometrics, 30, 109–126.

Deaton, A., & Paxson, C. (1994). Saving, growth, and aging in Taiwan. Chicago University Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Duru-Bellat, M., & Kieffer, A. (2008). From the Baccalauréat to higher education in France: Shifting inequalities. Population, 63(1), 119–154.

Goldthorpe, J. (2012). Understanding -and misunderstanding- social mobility in Britain: The entry of the economists, the confusion of politicians and the limits of educational policy. Barnett Papers in Social Research 2/2012.

Guillerm, M. (2017). Les méthodes de pseudo-panel et un exemple d’application aux données de patrimoine. Économie Et Statistique, 491–492, 119–140.

Jauneau, Y. (2009). Les employés et ouvriers non qualifiés : un niveau de vie inférieur d’un quart à la moyenne des salariés, Insee Première 1250, Juillet.

Jones, C., & Klenow, P. (2016). Beyond GDP? Welfare across countries and time. American Economic Review, 106(9), 2426–2457.

Le Rhun, B., & Pollet, P. (2011). Diplômes et insertion professionnelle. In France, portrait social. Insee Références. Paris.

Lefranc, A. (2018). Intergenerational earnings persistence and economic inequality in the long run: Evidence from French cohorts, 1931–75. Economica, 85(340), 808–845.

Murtin, F., Mackenbach, J., Jasilionis, D., & Mira d’Ercole, M. (2017). Inequalities in longevity by education in OECD countries: Insights from new OECD estimates. OECD Statistics Working Papers, No. 2017/02. OECD Publishing.

Stavins, R., Wagner, A., & Wagner, G. (2003). Interpreting sustainability in economic terms: Dynamic efficiency plus intergenerational equity. Economics Letters, 79, 339–343.

United Nations. (2013). National transfer accounts manual. Measuring and analysing the generational economy. United Nations.

Vallet, L.-A. (2017). Mobilité sociale entre générations et fluidité sociale en France. Le rôle de l’éducation. Revue De l’OFCE, 150(1), 27–67.

Acknowledgements

We thank the special editor of this issue and the anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of our manuscript and their insightful suggestions and comments. This research was supported by the Agence nationale de la recherche within the JPI MYBL framework (Award No. ANR-16-MYBL-0001-02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

d’Albis, H., Badji, I. Intergenerational equity by educational attainments in France. J Pop Research 38, 339–365 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-021-09274-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-021-09274-0