1. Tense use in narrative discourse

The temporal structure of narrative discourse is driven by events that move the story line forward, while states temporally overlap with the last introduced event (Partee Reference Partee1984; Hinrichs Reference Hinrichs1986; Kamp & Reyle Reference Kamp and Reyle1993). Stories are traditionally told in the past tense (Fleischman Reference Fleischman1990) and in languages with a perfective/imperfective distinction, grammatical aspect drives the state/event distinction: the perfective past introduces the main events, and the imperfective past describes states that make up the background of the story. For French, Kamp & Rohrer (Reference Kamp, Rohrer, Bäuerle, Schwarze and Stechow1983) show that a narrative discourse builds on the alternation of the Passé Simple and the Imparfait, where the Passé Simple reports foreground events, and the Imparfait reports background states.

The French novel L’Étranger, which appeared in 1942, stands out because the author Albert Camus does not use the Passé Simple to introduce the main events, but relies on the Passé Composé to do so. The configuration of an auxiliary (avoir ‘have’ or être ‘be’) in the present tense and a past participle makes the Passé Composé similar in morpho-syntax to the English Present Perfect. The Passé Composé has a broader distribution and a wider meaning than its English counterpart, though. The preference for the Passé Composé in L’Étranger is a deliberate choice of the author, and fits in with other features of the French novel such as the fact that it is written in the first person, and relates the events from the perspective of the protagonist Meursault. As the utterance time moves forward throughout the story, the novel reads as a diary with entries on different days.

The Passé Composé is subtly different from the Passé Simple, even when it is used in narrative discourse (more on the differences in Section 2). As Sartre (Reference Sartre1947) puts it, ‘every sentence is an island’ in L’Étranger, and he blames this on the use of the Passé Composé. It seems that the Passé Composé does not really tell the story, but describes the events as a list of things that happened. This factual style (Apothéloz Reference Apothéloz, Giancarli and Fryd2016) keeps the reader at a distance. The inability of the reader to engage in the universe of the novel matches the protagonist’s feeling of alienation from the rest of the world. Tense choice in L’Étranger thus has a strong literary effect.

This paper develops a linguistic analysis of the distribution and meaning of the verb forms used to translate the Passé Composé in L’Étranger in Italian, German, Dutch, (European) Spanish, (British) English, and (Modern) Greek. The novel’s tense use gives rise to a tricky translation problem. The literary effect of the Passé Composé pushes the translator to turn to a tense that maximizes the ‘island’ feeling referred to by Sartre (Reference Sartre1947), however, without going against the grammar of the target language. Translators are thus pushed to avoid narrative (perfective) pasts and maximize the use of their closest non-narrative counterparts. For the languages under investigation, these counterparts are tenses built on the auxiliary have/be + past participle. Following Dahl & Velupillai (Reference Dahl, Velupillai, Dryer and Haspelmath2013), we refer to these tenses as (present) have perfects or perfects for short. The literary effect of the Passé Composé thus makes L’Étranger a good source text to determine the range and limits of perfect use across languages.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 motivates the choice for a strictly form-based approach that labels all tenses that build on the auxiliary have/be + past participle as perfects. Under this definition, not only the English Present Perfect qualifies as a perfect, but so does the French Passé Composé, the Italian Passato Prossimo, the German Perfekt, etc. A form-based definition of the perfect creates room for a data-driven approach in which constraints on meaning are derived from the distribution of forms.

Section 3 outlines our Translation Mining methodology, and illustrates it with the set of verb forms used in the translation of the Passé Composé in Chapters 1–3 of L’Étranger in Italian, Spanish, Dutch, German, English, and Greek. We apply multidimensional scaling (Wälchli & Cysouw Reference Wälchli and Cysouw2012) to generate cartographic visualizations of the verb forms in the multilingual dataset, which we call temporal maps. The comparison of temporal maps across languages reveals a distribution of labor between perfect and past. We use past as a label for verb forms like the English Simple Past, the Spanish Pretérito Indefinido, the German Präteritum, etc. that are qualified as simple or perfective past tenses in traditional grammars. Rather than a dichotomy between perfect and past, we find a subset relation ranging from more liberal to stricter perfect languages.

In Section 4, the investigation of key examples where the perfect gives way to a past shows how the crosslinguistic distribution mirrors the grammatical constraints on perfect meaning. The linguistic analysis relies on lexical semantics (aspectual class), compositional semantics (past time reference of the underlying event), dynamic semantics (narrative or non-narrative contexts), and pragmatics (deixis, information structure). Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. A comparative study of the perfect

The French Passé Composé is a compound tense formed by an auxiliary (avoir ‘have’ or être ‘be’) in the present tense and a past participle, for example, il a réussi ‘he has succeeded’, il est parti ‘he has left’. Other European languages have comparable forms in their grammar, for example, the English Present Perfect, the Spanish Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto, or the German Perfekt. Dahl & Velupillai (Reference Dahl, Velupillai, Dryer and Haspelmath2013) call this morpho-syntactic configuration the have perfect, and treat it as a western European phenomenon. We restrict ourselves to a subset of the western European languages that instantiate this construction, and simply refer to these forms as present perfect or perfects for short.

Even within the relatively small geographical area in which we find the construction have/be + past participle, perfects do not have the same distribution or the same meaning. According to Lindstedt (Reference Lindstedt and Dahl2000) and Dahl & Velupillai (Reference Dahl, Velupillai, Dryer and Haspelmath2013), the French Passé Composé has extended its use to the point that it has become a perfective past and no longer qualifies as a perfect ‘gram’ in the typological sense. This meaning shift of the perfect extends to varieties of Italian spoken in northern Italy (Bertinetto Reference Bertinetto1986), and varieties of German spoken in the south of Germany and Switzerland (Löbner Reference Löbner, Kaufmann and Stiebels2002; Schaden Reference Schaden2009). Dahl & Velupillai (Reference Dahl, Velupillai, Dryer and Haspelmath2013) situate Greek in the periphery of the have perfect area, because it has a more restricted perfect. For Comrie (Reference Comrie1976), Dahl (Reference Dahl1985), Bybee, Perkins & Pagliuca (Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994), and Squartini & Bertinetto (Reference Squartini, Bertinetto and Dahl2008), the patterns fit into a common diachronic development from perfect to past, called the Aorist drift. This paper is restricted to a synchronic perspective, and the diachronic implications of the empirical findings are left for further research.

The typological observations raise the question of the delimitation between (perfective) past and perfect. The English Present Perfect is often put forward as a prototypical instance of the perfect gram (Dahl & Velupillai Reference Dahl, Velupillai, Dryer and Haspelmath2013). Comrie (Reference Comrie1976), McCawley (Reference McCawley1981), Michaelis (Reference Michaelis1994), Portner (Reference Portner2003, Reference Portner, von Heusinger, Maienborn and Portner2011), Nishiyama & Koenig (Reference Nishiyama and Koenig2010), Kamp, Reyle & Rossdeutscher (Reference Kamp, Reyle and Rossdeutscher2015), and others distinguish up to four readings of the Present Perfect:

The core meaning of the Present Perfect in (1) is a past event with current relevance. According to Reichenbach (Reference Reichenbach1947), both the Present Perfect and the Simple Past locate an event in the past, but for the Simple Past, the perspective (or reference time) is on the past event, whereas for the Present Perfect, the reference time is identified with the speech time.

This difference explains why a past time adverbial requires a Simple Past in (2a), and is incompatible with the Present Perfect in (2b) (Klein Reference Klein1992; Declerck Reference Declerck2006).

Partee (Reference Partee1973, Reference Partee1984) takes the Simple Past to be definite and anaphoric, whereas the Present Perfect is conceived as indefinite and quantificational. Because of its non-anaphoric nature, the Present Perfect is not suitable for the description of sequences of past events in narrative discourse:

In (3), the order in which the events are described matches their natural temporal order. As such, there is a discourse relation of narration between the two clauses (Lascarides & Asher Reference Lascarides and Asher1993). Anaphoricity provides the key to narrative discourse, which led to dynamic semantic analyses of the Simple Past, but not the Present Perfect in Partee (Reference Partee1984), Hinrichs (Reference Hinrichs1986), Kamp & Reyle (Reference Kamp and Reyle1993), and Lascarides & Asher (Reference Lascarides and Asher1993). Current analyses of the Present Perfect are more sophisticated than Reichenbach’s analysis, but formal details aside, Michaelis (Reference Michaelis1994), Portner (Reference Portner2003, Reference Portner, von Heusinger, Maienborn and Portner2011), Nishiyama & Koenig (Reference Nishiyama and Koenig2010), Kamp et al. (Reference Kamp, Reyle and Rossdeutscher2015) and others are all set up to account for the sentence-level phenomena in (1) and (2), which locate the underlying event in an extended ‘now’, and exclude the Present Perfect from past time reference and narrative discourse as in (3).

Within the western European area, crosslinguistic investigations on patterns of compatibility with past time adverbials and narrative use are carried out by Rothstein (Reference Rothstein2006), De Swart (Reference De Swart2007), Schaden (Reference Schaden2009), and Kamp et al. (Reference Kamp, Reyle and Rossdeutscher2015).Footnote 2 They report configurations that do not match the contrasts in (2) and (3). Comrie (Reference Comrie1976), Binnick (Reference Binnick1991), and Klein (Reference Klein1992) point out that the ban on past time adverbials is specific to the English Present Perfect, and does not generalize to languages like Dutch, French, and German, as we see in (4).

The sentences in (4b), (4c), and (4d) are direct translations of (4a) in the Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd, the Passé Composé, and the Perfekt. In contrast to the English Present Perfect, the perfect forms in Dutch, French, and German are compatible with an adverbial that locates the event at a specific time in the past.

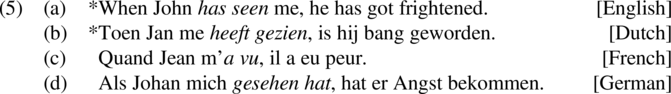

Reports on narrative use of the Italian Passato Prossimo, the French Passé Composé and the German Perfekt are found in Bertinetto (Reference Bertinetto1986), Vet (Reference Vet1992), and Löbner (Reference Löbner, Kaufmann and Stiebels2002) respectively. The criterion of appearance in when-clauses proposed by Boogaart (Reference Boogaart1999) supports these observations, as illustrated in (5) (from De Swart (Reference De Swart2007)):

The translations of (5a) in (5b)–(5d) show that the French and German perfect verb forms are fine in when-clauses, whereas the Present Perfect in (5a) bans narrative use. Note that Dutch patterns with French and German in its compatibility with past time adverbials (4b), whereas it behaves like English in resisting narrative use for the Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd in (5b). The fact that the two criteria in (2) and (3) do not yield the same results for all languages further complicates the crosslinguistic picture.

At this point, we do not doubt the characterization of the English Present Perfect as setting up a past event with current relevance (Michaelis Reference Michaelis1994; Portner Reference Portner2003, Reference Portner, von Heusinger, Maienborn and Portner2011; Nishiyama & Koenig Reference Nishiyama and Koenig2010; Kamp et al. Reference Kamp, Reyle and Rossdeutscher2015). We also see how this analysis can account for key features of the Spanish Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto (Schaden Reference Schaden2009; Howe Reference Howe2013). However, if the perfects in French, German, and Italian retain the morpho-syntactic form have/be + past participle, but tolerate past time adverbials and narrative use, we cannot analyze them on a par with the English Present Perfect. We might then be tempted to conclude with Lindstedt (Reference Lindstedt and Dahl2000) and Dahl & Velupillai (Reference Dahl, Velupillai, Dryer and Haspelmath2013) that some perfects have developed into a perfective past, and that the grammars of French, Italian, and German no longer contain the perfect ‘gram’. However, this account would need to be worked out to cover the intermediate position of Dutch and would fail to make relevant predictions for the perfect in Greek. We also find that a perfective past analysis is not agreed upon in the rich literature on the French Passé Composé (Vet Reference Vet1992; Caudal & Vetters Reference Caudal, Vetters, Labeau, Vetters and Caudal2007; De Swart Reference De Swart2007; Schaden Reference Schaden2009; Bres Reference Bres, Stosic, Flaux and Vet2010; Apothéloz Reference Apothéloz, Giancarli and Fryd2016). Despite the fact that the Passé Composé has effectively replaced the Passé Simple in the spoken language, including in the highest registers (Van der Klis, Le Bruyn & De Swart Reference Van der Klis, Le Bruyn and de Swart2017), some proposals align with Lindstedt’s and Dahl & Velupillai’s but others insist that the Passé Composé retains core ingredients of the perfect meaning and cannot qualify as a perfective past.

Even if we set aside the fine-grained discussions on the status of the French Passé Composé, the empirical picture that emerges from our brief review is clear. There is too much variation to restrict ourselves to a rigid perfect/perfective past dichotomy with the English Present Perfect being the prototypical restrictive perfect and the French Passé Composé being the prototypical liberal perfect turned perfective past. The variation we have surveyed calls for a more flexible approach that allows for intermediate positions – for example, for Dutch – and more extreme positions on the conservative side – for example, for Greek. Accounting for the distribution of western European perfects then forces us to let go of the idea that they should qualify either as perfects or perfective pasts. Rather, the variation we find bears witness to a distribution of labor between perfects and pasts. We follow Michaelis (Reference Michaelis1994) and Schaden (Reference Schaden2009) in framing this distribution of labor in terms of a competition between perfect and past.

Once we let go of the idea that tense forms should either qualify as perfects or perfective pasts, we no longer have to explain away bigger or smaller deviations from perfect or perfective past prototypes. This allows us to build up a form-based typology of perfects that does justice to the full range of variation we find. We aim to bring out this variation in a data-driven way by looking at the tenses used to translate the Passé Composé, which we assume – in line with the literature – to be the most liberal perfect. By bringing in the broadest range of languages to date, we confirm the detailed findings that have been reported for individual perfects while at the same time establishing their place in the typology of perfects and surveying the dimensions of variation.

3. How Translation Mining reveals the distribution of labor between perfect and past

With Section 4, the current section constitutes the core of our paper. We introduce Translation Mining and study the use, distribution, and meaning of the perfect. The overall approach and hypotheses are outlined in Section 3.1. Our dataset consists of all instances of the Passé Composé extracted from Chapters 1–3 of L’Étranger and their translations in Italian, German, Dutch, Spanish, English, and Greek. Section 3.2 describes in more detail how Translation Mining generates an annotated dataset of tuples of verb forms in the seven languages. In Section 3.3, we showcase the multidimensional scaling component of Translation Mining and use it to map out the variation in tense use across languages. This strategy reveals a subset relation in the crosslinguistic distribution of the perfect and supports a competition between perfect and past. In Section 3.4, we show how the integrated setup of Translation Mining allows to access the contexts in which the perfect gives way to the past from one language to the next. We exploit this feature in Section 4 to survey the dimensions of variation of the perfect.

3.1 Overall approach and hypotheses

The use of parallel corpora for contrastive analyses is not new (see e.g. Bogaards Reference Bogaards2019 and references therein). A clear precursor of our work is Dahl & Wälchli’s (Reference Dahl and Wälchli2016) investigation of the perfect and iamitives (from Latin iam ‘already’). Their work also relies on multidimensional scaling (Wälchli & Cysouw Reference Wälchli and Cysouw2012) to find patterns of variation in a multilingual dataset, so we share the overall approach. However, Dahl & Wälchli (Reference Dahl and Wälchli2016) adopt a full-blown typological (world) perspective and abstract away from individual languages to compare groups of languages. In contrast, we focus on the have perfects in western European languages, and investigate variation at the level of individual languages. The same methodology can thus be exploited to study both macro- and meso-variation.

A strictly form-based definition of the perfect leads us to formulate the following hypotheses. If Lindstedt (Reference Lindstedt and Dahl2000) and Dahl & Velupillai (Reference Dahl, Velupillai, Dryer and Haspelmath2013) are right, we may expect the Passé Composé in L’Étranger to be translated as a Perfekt in German or a Passato Prossimo in Italian (Bertinetto Reference Bertinetto1986 for Italian; Löbner Reference Löbner, Kaufmann and Stiebels2002 for German). In contrast, languages like English and Spanish should resort to the Simple Past and the Pretérito Indefinido in contexts where the grammar of these languages does not allow a perfect (Schaden Reference Schaden2009). Based on the patterns in (4) and (5), as well as crosslinguistic comparisons in De Swart (Reference De Swart2007) and Le Bruyn, Van der Klis & De Swart (Reference Le Bruyn, van der Klis and de Swart2019), we expect the Dutch Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd to be more frequent than the Spanish and English perfects, but less so than the German and Italian ones. The inclusion of Greek, a language considered to have a more restricted use of the perfect than English (Dahl & Velupillai Reference Dahl, Velupillai, Dryer and Haspelmath2013), allows us to identify the core of perfect use shared by all languages.

The overall hypotheses are in line with existing typological and semantic literature. Our data-driven approach allows us to put them to the test, establish how they interact in the broadest typology to date, and survey the underlying dimensions of variation. The integrated setup of Translation Mining allows us to study these dimensions in detail and link them to more fine-grained observations in the literature that have hitherto played a reduced role in the typology of the perfect.

3.2 Data collection and annotation

Our dataset consists of all the occurrences of the Passé Composé extracted from Chapters 1–3 of L’Étranger, aligned with their translations in Italian, German, Dutch, Spanish, English, and Greek, and enriched with a morpho-syntactic labeling of the translation of the type Present Perfect, Simple Past, Simple Present, etc.Footnote 3

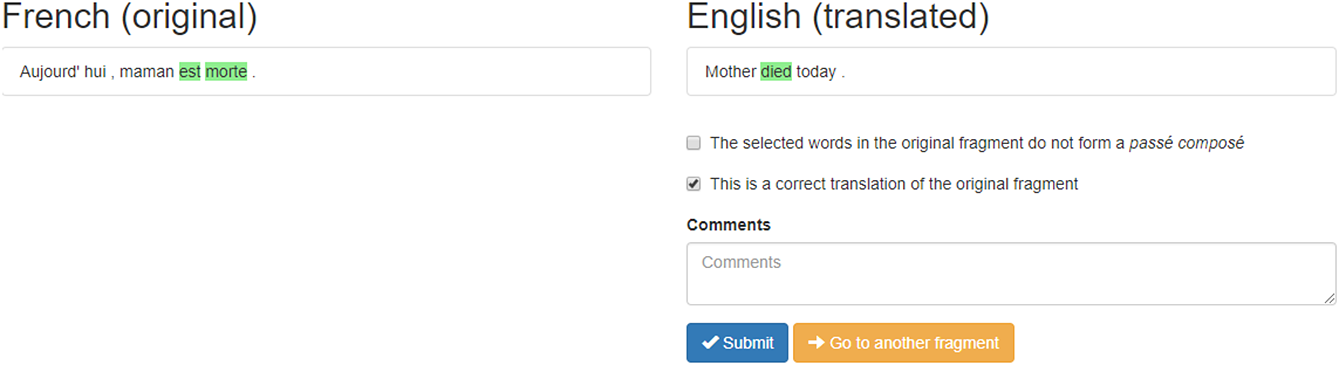

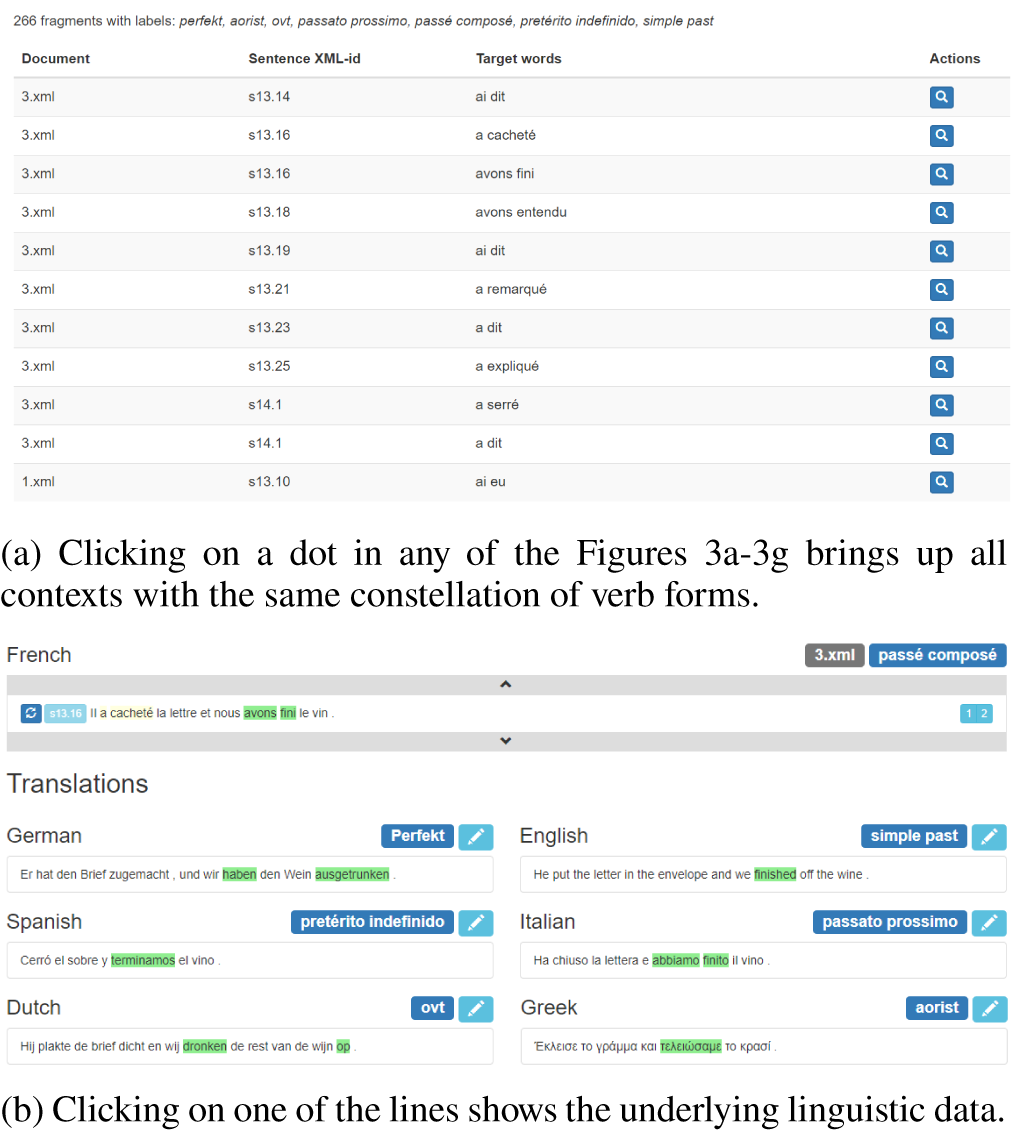

To create this dataset, we converted the original and the translations into electronically readable documents, extracted all the instances of the French Passé Composé with a purpose-built algorithm (PerfectExtractor), and aligned these with their translations in the different languages. The alignment was done by human annotators in a custom-made annotation application dubbed TimeAlign.Footnote 4 Figure 1 showcases the annotation interface.

Figure 1 (colour online) The TimeAlign annotation interface.

The annotator’s task in TimeAlign was to select the relevant verb form that translates the Passé Composé. For the context in Figure 1, this means the annotator had to click died as the verb form that translates est morte. If something had gone wrong in the alignment or extraction phase, the annotator could remove the datapoint from the dataset by unticking the option ‘This is a correct translation of the original fragment’. Datapoints that led to a nonverbal construction (e.g. a noun phrase) in the target language were also removed in this way. The outcome is a dataset of 348 contexts in which all languages use a verb form as the translation of the Passé Composé.

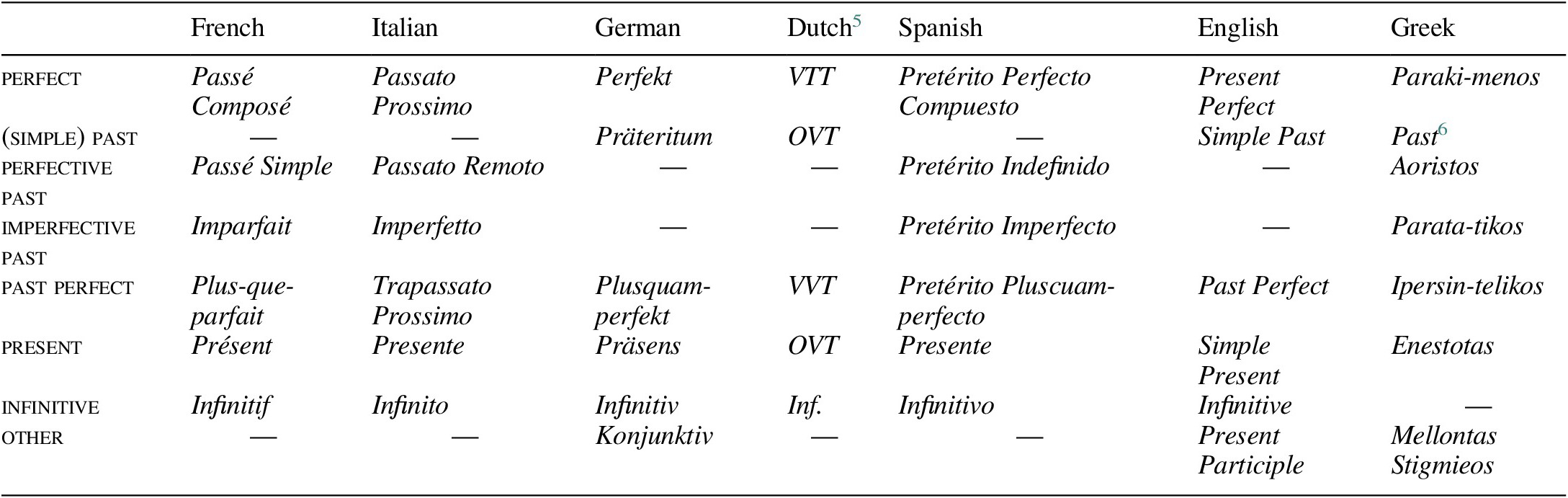

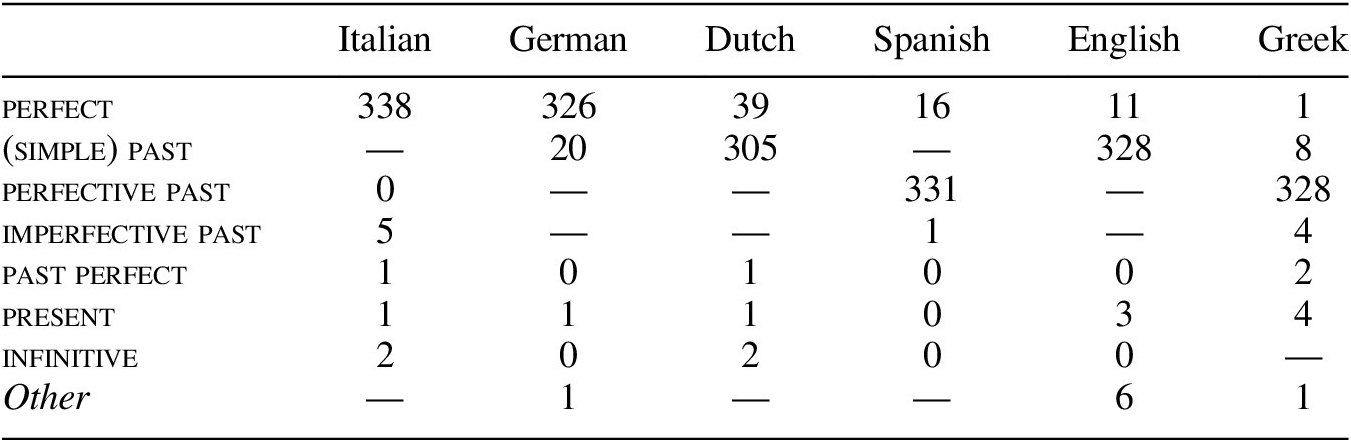

After the alignment phase, the data were exported to a spreadsheet, and annotated manually for the verb form used. The annotation protocol follows the terminology familiar from the traditional grammar of the language in question, so we use Present Perfect for English, Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto for Spanish, Perfekt for German, etc. Under the morpho-syntactic definition adopted in Section 2, we categorize the French Passé Composé, the Italian Passato Prossimo, and the German Perfekt as perfects. The German Präteritum, the Dutch Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, and the English Simple Past qualify as (simple) past forms. The Spanish Pretérito Indefinido and the Greek Aoristos are perfective pasts. Table 1 collects all the verb forms in the categories perfect, (simple) past, perfective past, imperfective past, past perfect, present, infinitive, and an ‘other’ category.

Table 1 Correspondences between language-specific verb forms and tense-aspect categories. The ‘other’ category lists forms that are not classified in one of the main tense-aspect categories, but do appear as forms in the current dataset.

As the annotation is always carried out at a language-specific level, we generate the descriptive statistics in Table 2 with the labels per language. To facilitate the crosslinguistic comparison, the rows order the forms by morpho-syntactic category. A ‘—’ means that such a form is not an ingredient of the grammar (Spanish does not have a simple past form, German does not have a perfective past form), while a ‘0’ means that particular form does not show up in the dataset (e.g. English has a past perfect form, but it happens not to be used as a translation of the Passé Composé in Chapters 1–3 of L’Étranger). The order of presentation in Table 2 takes us from languages with the most frequent to least frequent perfect use in the dataset.

Table 2 Inventory of the verb forms used in the translations of the 348 instances of the Passé Composé in L’Étranger.

Table 2 shows that Italian uses the Passato Prossimo as freely as French uses the Passé Composé: in 338 out of 348 cases, the perfect from the original is maintained in the Italian translation. With 326 occurrences, the number for the German Perfekt is lower, but still very high. With 39 instances of the Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd, the number of Dutch perfects is much lower than German, but higher than Spanish and English, where we find only 16 instances of the Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto and 11 instances of the Present Perfect. With only one occurrence of the Parakimenos, Greek displays a rare use of the perfect.

The numbers in Table 2 are useful and seem to confirm the coarse-grained hypotheses that we proposed in Section 3.1. They only sketch overall tendencies, though, and do not allow us to establish how the perfects in the different translations really relate to one another. As they stand, the numbers, for instance, do not allow us to decide whether the distributions of Spanish and Dutch perfects are in a subset/superset relation, overlap, or are simply orthogonal to one another. To get more grip on the data, we have to move from frequencies of tense use per language to frequencies of combinations of tense use across languages. To do so, we match each of the 348 datapoints with the crosslinguistic tense use that they display. We represent this tense use as a 7-tuple listing that the tenses used (for example,

![]() $ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Perfekt, Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

$ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Perfekt, Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

![]() $ \Big\rangle $

). By comparing the datapoints on the basis of their underlying 7-tuples, we can evaluate, for instance, how often Spanish and Dutch perfects co-occur as translations of the Passé Composé and establish how they relate to one another.

$ \Big\rangle $

). By comparing the datapoints on the basis of their underlying 7-tuples, we can evaluate, for instance, how often Spanish and Dutch perfects co-occur as translations of the Passé Composé and establish how they relate to one another.

Looking into the frequencies of their underlying 7-tuples, we find that the great majority of datapoints display the 7-tuple

![]() $ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Perfekt, Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

$ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Perfekt, Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

![]() $ \Big\rangle $

(266 out of 348 datapoints). We conclude that the Passé Composé is usually translated by a perfect in Italian and German, and by a simple or perfective past in Dutch, English, Spanish, and Greek. The numbers suggest that the translators relied on the expanded use of the perfect in Italian (Bertinetto Reference Bertinetto1986) and German (Löbner Reference Löbner, Kaufmann and Stiebels2002). The similarities between Spanish and English provide empirical evidence in support of claims in Dahl & Velupillai (Reference Dahl, Velupillai, Dryer and Haspelmath2013) and Schaden (Reference Schaden2009) that these languages have not extended their have perfect in the direction of a past.

$ \Big\rangle $

(266 out of 348 datapoints). We conclude that the Passé Composé is usually translated by a perfect in Italian and German, and by a simple or perfective past in Dutch, English, Spanish, and Greek. The numbers suggest that the translators relied on the expanded use of the perfect in Italian (Bertinetto Reference Bertinetto1986) and German (Löbner Reference Löbner, Kaufmann and Stiebels2002). The similarities between Spanish and English provide empirical evidence in support of claims in Dahl & Velupillai (Reference Dahl, Velupillai, Dryer and Haspelmath2013) and Schaden (Reference Schaden2009) that these languages have not extended their have perfect in the direction of a past.

Interestingly, we also find other 7-tuples to be fairly frequent. There are 18 instances with the 7-tuple

![]() $ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Perfekt, Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

$ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Perfekt, Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

![]() $ \Big\rangle $

, in which Dutch uses a perfect along with French, Italian, and German. Furthermore, there are 15 instances of the 7-tuple

$ \Big\rangle $

, in which Dutch uses a perfect along with French, Italian, and German. Furthermore, there are 15 instances of the 7-tuple

![]() $ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Präteritum, Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

$ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Präteritum, Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

![]() $ \Big\rangle $

, in which German uses a past, along with Dutch, Spanish, English, and Greek. These frequencies are much lower than that of the datapoints with the dominant 7-tuple, but the numbers are high enough that they might suggest a specific linguistic constellation. We tentatively conclude that German is not quite as liberal as French and Italian, and Dutch is possibly not as restricted as Spanish and English.

$ \Big\rangle $

, in which German uses a past, along with Dutch, Spanish, English, and Greek. These frequencies are much lower than that of the datapoints with the dominant 7-tuple, but the numbers are high enough that they might suggest a specific linguistic constellation. We tentatively conclude that German is not quite as liberal as French and Italian, and Dutch is possibly not as restricted as Spanish and English.

Even though a closer study of the underlying data is required, the preliminary analysis of datapoints on the basis of their 7-tuples shows that our multilingual dataset allows us to probe the way that perfects across languages relate to one another. However, so far we have only looked into three of the 29 attested 7-tuple types. Identifying the relevant patterns across all 29 is hard to process, both for the researcher and the reader. This is where the multidimensional scaling component of Translation Mining comes in. We introduce this component in Section 3.3 and show how we link its output to the underlying data in Section 3.4.

3.3 A cartographic inventory of the data

Multidimensional scaling (MDS) is a computational technique that recognizes distributional patterns in complex datasets and generates a two-dimensional visualization of such patterns (Wälchli & Cysouw Reference Wälchli and Cysouw2012). The application of MDS to our dataset clusters datapoints based on their underlying tense use as listed in their corresponding 7-tuples.Footnote 7

The input for MDS in our study is a dissimilarity matrix that we established for our 348 datapoints based on their corresponding 7-tuples. Two datapoints are maximally similar if every language uses the same tense in the corresponding 7-tuples. The more tenses differ, the more the datapoints are dissimilar. For concreteness, let us assume we have Datapoints 1, 2, and 3 with their corresponding 7-tuples:

-

1.

$ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Perfekt, Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

$ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Perfekt, Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

$ \Big\rangle $

$ \Big\rangle $

-

2.

$ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Perfekt, Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

$ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Perfekt, Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

$ \Big\rangle $

$ \Big\rangle $

-

3.

$ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Präteritum, Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

$ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Präteritum, Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

$ \Big\rangle $

$ \Big\rangle $

Datapoint 2 is only different from Datapoint 1 in its Dutch tense use. The degree of dissimilarity between the two points is thus

![]() $ \frac{1}{7} $

. Datapoint 3 is different from Datapoint 1 in its German and Dutch tense use. Their degree of dissimilarity is thus

$ \frac{1}{7} $

. Datapoint 3 is different from Datapoint 1 in its German and Dutch tense use. Their degree of dissimilarity is thus

![]() $ \frac{2}{7} $

and turns out to be slightly higher than the degree of dissimilarity between Datapoints 1 and 2. The full dissimilarity matrix contains pairwise comparisons of all 348 datapoints.

$ \frac{2}{7} $

and turns out to be slightly higher than the degree of dissimilarity between Datapoints 1 and 2. The full dissimilarity matrix contains pairwise comparisons of all 348 datapoints.

The output of MDS in our study can intuitively be thought of as a two-dimensional representation clustering datapoints based on their relative (dis)similarity. In essence, MDS clusters datapoints in the same way as we did for the three 7-tuple types we studied in Section 3.2. The advantage of the MDS output is that it does this for all 348 datapoints with their 29 attested 7-tuple types while taking into account the frequency and interactions of the latter, and presenting the data in a visual format.

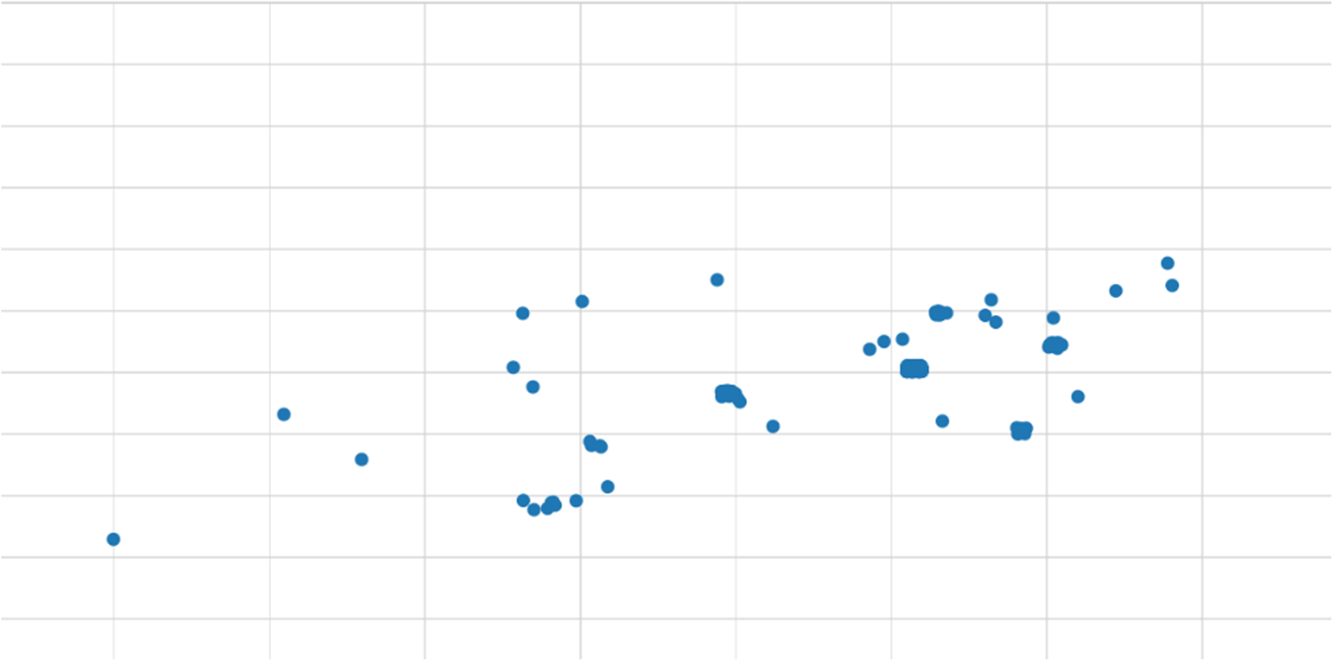

Figure 2 presents the raw MDS output. Dots that are closely together represent similar datapoints, whereas dots that are far away from each other represent dissimilar datapoints. Given that (dis)similarity is based on tense use through the 7-tuples corresponding to the datapoints, dots that are closely together display a similar tense use whereas dots that are far away from each other display dissimilar tense use. We added some jitter to the output, so that not all the dots that represent datapoints displaying the same 7-tuple end up on top of each other. Even so, we should be aware of the fact that some dots hide others, which explains why we see fewer than 348 dots in Figure 2.

Figure 2 (colour online) Raw MDS output based on the 7-tuples of our 348 datapoints.

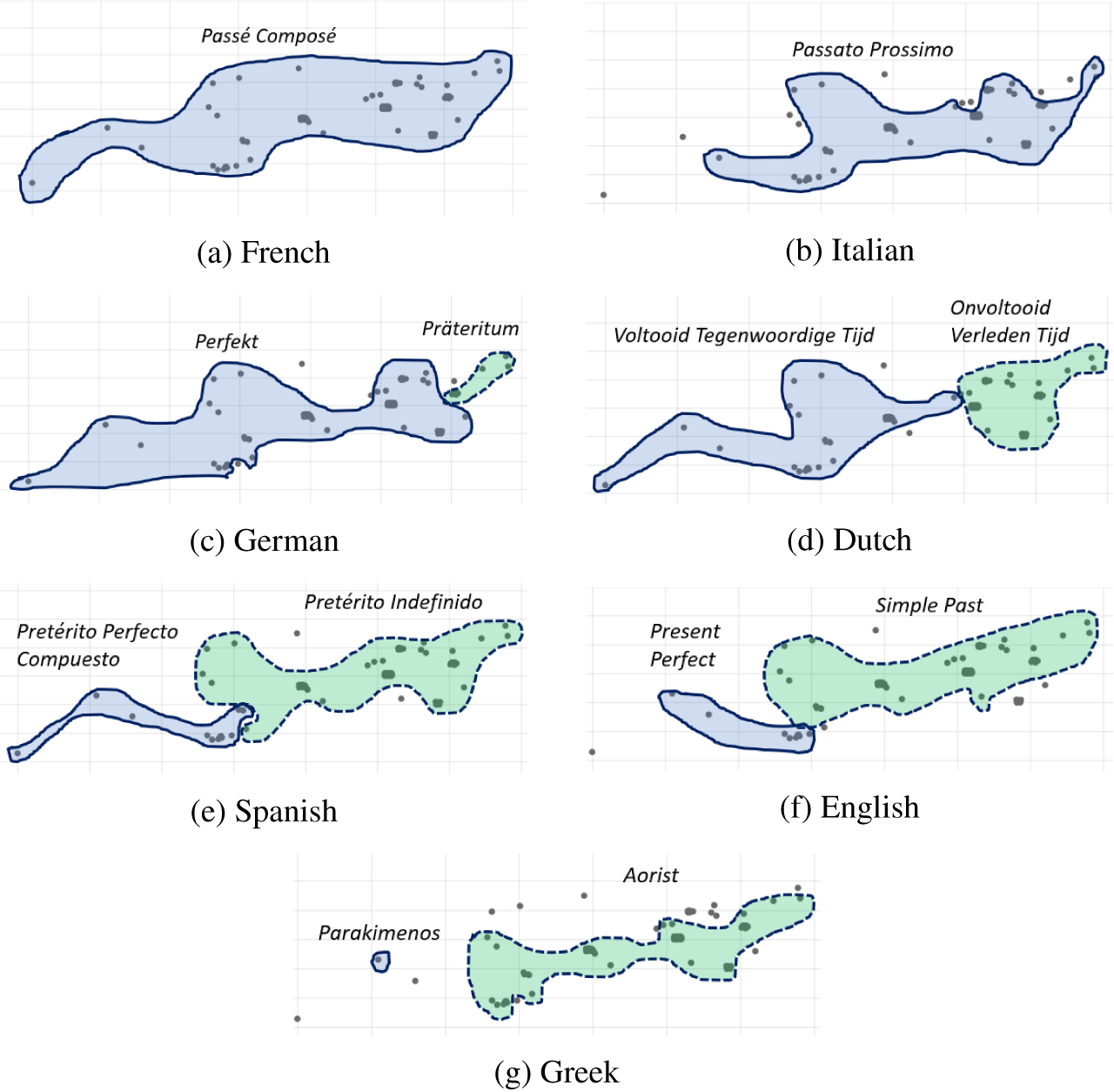

Figure 2 clusters all datapoints based on their corresponding 7-tuples. As one could expect with 29 attested 7-tuple types, clusters are not always easy to distinguish and the interpretation of this raw output might still feel difficult. To shed light on the data, we propose to look at them through the lens of each language. We generate seven copies of the raw output in Figure 2 in which the language-specific verb form determines the color of the dots. Based on the correspondences in Table 1 between language-specific verb forms and generic categories, we color the perfect dots blue, and the (perfective) past dots green. We draw borders around the clusters of blue and green dots to determine the perfect domain (solid border) and past domain (dotted border) in each language. Figures 3a–3g show the output of the process of adding the language-specific markup. We refer to these figures as temporal maps.

Figure 3 (colour online) Temporal maps displaying perfect and past use per language.

Figures 3a–3g are all copies of the raw MDS output in Figure 2, with language-specific markup indicating the clusters of perfect and past datapoints. Figure 3 presents the languages from left to right and from top to bottom in the order of most frequent to least frequent perfect use, based on the descriptive statistics in Table 2.

The French map in Figure 3a shows a single blue domain with a solid border. This is unsurprising, because we only extracted Passé Composé forms from L’Étranger. The solid-bordered blue domains in the Italian and German versions of the map in Figures 3b and 3c are quite large, which reflects the extended use that these languages make of the Passato Prossimo and the Perfekt respectively. The perfect domain of the Dutch map in Figure 3d is between the large blue domains of Italian and German and the small blue domains of English and Spanish in Figures 3f and 3e. The perfect domain in Figure 3g consists of a single blue dot, representing the single instance of the Greek Parakimenos.

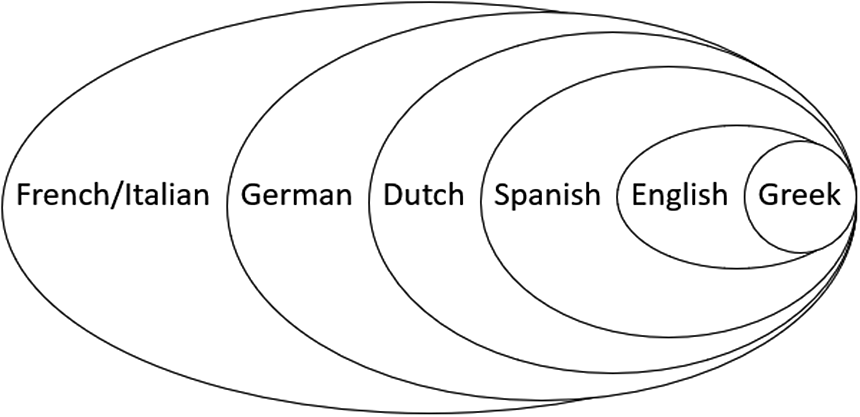

The striking feature of Figure 3 is that frequency correlates with distribution over contexts: every time a dot loses its blue color and becomes green, it remains green in the following maps. This shrinking of the blue domain with a solid line as its border from right to left and top to bottom in Figures 3b–3g indicates that the contexts in which the perfect is appropriate in German are a subset of the contexts in which French and Italian use the perfect, the Dutch perfect covers a subset of the contexts in which German uses the perfect, and so on. The pattern in Figure 3 supports the subset relation in Figure 4, which indicates that perfect distribution is narrowed down from each language to the next.

Figure 4 Subset relation in the distribution of the perfect.

The gradual reduction of the blue perfect domain from top to bottom in Figure 3 correlates with an increase of the green domain with a dotted line as its border, that is, the past contexts. Starting with the German map in Figure 3c, we see the emergence of a green cluster with a dotted line at the right of the map. The past domain shows the inverse subset relation from Figure 4: the green dots that signal past tense use in German are a subset of the set of contexts that take the past tense in Dutch, and so on. The fact that the blue cluster with the solid border shrinks while the green cluster with the dotted border expands at every transition between Figures 3b–3g does not only support the subset relation in Figure 4, but provides evidence in favor of a distribution of labor or a competition between perfect and past (Michaelis Reference Michaelis1994; Schaden Reference Schaden2009). The data support a scale with extremes, but also intermediate positions, rather than a strict dichotomy between perfect- and past-oriented languages.

The distribution of green and blue clusters in Figures 3a–3g leads us to think that the contexts more toward the left on the temporal map reflect more typologically stable characteristics of the perfect, whereas there is more competition between perfect and past forms in the contexts toward the right of the map. We hypothesize that the stepwise restriction in distribution of perfect forms in the dataset is indicative of a gradual narrowing down of perfect meaning. To support the inferences from distribution to grammar, we need access to the contexts underlying the datapoints in the map. In that way, we can determine for each language the linguistic criteria that drive perfect and past use. If these linguistic criteria differ from language to language, we can connect the grammar of individual languages to the subset relation in Figure 4. Section 3.4 introduces the interactive map interface that Translation Mining comes with and shows how it allows us to go back and forth between maps and underlying data.

3.4 An interactive map interface: From maps to the underlying data

Recall that all dots in the maps in Figures 3a–3g represent contexts with the same configuration of verb forms. Even though our temporal maps are generated solely on the basis of the tense labels in the 7-tuples corresponding to the datapoints, the linguistic data that we can draw on are significantly richer and include the lexical information of the verbs as well as their full contexts of use in L’Étranger and its translations. As the perfect and past clusters are very well delineated, it makes sense to assume that the distribution of verb forms in context reflects the grammar of tense and aspect in the individual languages. The investigation of the examples underlying the dots that switch from perfect to past from one map to the other in the series enables us to detect the linguistic principles driving the subset relation in Figure 4. This is where the integrated setup of Translation Mining comes in.

Translation Mining combines a database with annotation and analysis tools. Unlike other MDS analysis software, it thus allows us to create a direct link between the datapoints in the MDS output and the underlying data. To exploit this option, we have turned the maps that MDS generates interactive. In the Translation Mining interface, one can click any of the dots on the maps in Figures 3a–3g to arrive at all the contexts that have the same underlying 7-tuple (Figure 5a). Another click reveals the underlying data, specifically, the original context with its translations enriched with their morpho-syntactic labeling (Figure 5b).

Figure 5 (colour online) The interactive Translation Mining interface.

In Section 4, we strategically use this interactive map interface to zoom in on the cut-off points between the clusters as the key to understanding crosslinguistic variation. No noticeable difference between Italian and French exists, but we investigate the contexts at the borderline of the perfect and past in Figures 3b–3g for the other languages. For instance, the comparison of Italian and German in Figures 3b and 3c reveals that German makes fairly extended use of the perfect, but there is a cluster on the far right of the map in which French and Italian use a perfect, and German a past. By using the interactive interface, we can click on the datapoints in which German uses a Präteritum and analyze the individual examples to try and explain why the German translator avoided the Perfekt in these contexts. The going back and forth between maps and their underlying data via the interactive interface connects language use to grammar.

4. From language use to grammatical meaning: A linguistic analysis of the variation

As outlined in Section 1, we take the literary value of the Passé Composé to push the translator to maximize perfect use in the target language. The translator needs to overcome the translation bias to switch to a different verb form, so when this happens we are most likely dealing with a configuration in which the perfect is blocked by the tense-aspect grammar of the target language. In this section, we exploit the interactive interface to provide a linguistic interpretation of the boundaries on perfect use between Italian and German, German and Dutch, Dutch and Spanish, and Spanish and English in Figures 3b–3f. Section 4.1 starts with the cut-off points between Italian and German in Figures 3b and 3c. Sections 4.2 –4.4 report on the boundaries between German/Dutch, Dutch/Spanish, and Spanish/English respectively. Section 4.5 comments on the classical configurations of perfect meaning that share perfect use in all languages, and highlights the limited use of the perfect in Greek, as shown in Figure 3g. Section 4.6 summarizes the findings.

To situate the examples, here is a global idea of the content of Chapters 1–3 of L’Étranger. In the first chapter, we learn about the death of Meursault’s mother, and follow him to the old people’s home about fifty kilometers from his hometown, Algiers, for the funeral. Chapters 2 and 3 relate events of Meursault’s daily life at the office and at home, as well as his emerging love affair with Marie. Recall that the novel is written in the first person, so we view the events from the perspective of the protagonist.

4.1 From Italian to German: The role of stative verbs

The German translation makes a fairly liberal use of the Perfekt, but even so, there are 20 occurrences of the Präteritum in the dataset. They are clustered in the green domain with a dotted border at the far right of Figure 3c. German sides with Dutch, Spanish, English, and Greek in its preference of the past: access to the data underlying the dots shows that in 15 contexts, the Präteritum appears as part of the 7-tuple

![]() $ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Präteritum, Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

$ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Präteritum, Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

![]() $ \Big\rangle $

. In 11 out of 15 cases, we are dealing with a stative verb like to be, to have as in (6) or a verb describing a cognitive state (to think, to find, to believe, to want, etc.), as we see in (7).

$ \Big\rangle $

. In 11 out of 15 cases, we are dealing with a stative verb like to be, to have as in (6) or a verb describing a cognitive state (to think, to find, to believe, to want, etc.), as we see in (7).

Based on the subset relation in Figure 4, we expect the languages displayed in Figures 3d–3f to also use a past form in this context. The translations in (6d)–(6f) and (7d)–(7f) confirm this by the use of the Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd in Dutch, the Pretérito Indefinido in Spanish, and the Simple Past in English.

For the 5 contexts outside the dominant pattern, we find that the verb form varies, but the verb is always stative. The example with the modal verb have to in (8) follows the pattern in (6) and (7) except for the switch to the past perfect in the Italian translation:

The conclusion that stative verbs have a special status in our dataset may come as no surprise to those who are familiar with the literature on the English Present Perfect, in which stative verbs with continuative meanings as in (1c) play an important role (Michaelis Reference Michaelis1994; Portner Reference Portner2003, among others). However, the stative verbs discussed here occur in narration: the protagonist finds himself feeling happy when he leaves the office in (6), and the wish to smoke a cigarette in (7) or the need to acquire a black tie and armband in (8) comes up as the next relevant situation in the story line. These contexts are thus significantly different from the continuative contexts that we know from the English literature. Interestingly, though, they do echo findings in the recent literature on the German Perfekt. Nilsson (Reference Nilsson2016) experimentally establishes that stativity vs. dynamicity is a crucial factor in the competition between the Perfekt and the Präteritum. We confirm the relevance of this finding from a crosslinguistic perspective and formulate a lexical generalization for the cut-off point between French/Italian on the one hand and German/Dutch/Spanish/English/Greek on the other hand: French and Italian tolerate stative verbs in the perfect in narrative sequences, whereas the other languages do not, and switch to the past in such contexts. Lexical semantics is thus one of the ingredients of the grammar of the perfect.

4.2 From German to Dutch: Narrative use

As can be seen in the sizable expansion of the past domain between the maps of Figures 3c and 3d, Dutch makes a more restricted use of the perfect than German. The descriptive statistics in Section 3.2 indicate that there are 20 instances of the German Präteritum in the dataset against 305 instances of the Dutch Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd. We find 19 occurrences of the Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd in contexts in which German uses a Präteritum, which confirms the special status of stative verbs in the dataset, as well as the subset relation in Figure 4. The most frequent 7-tuple in the dataset is the configuration

![]() $ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Perfekt, Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

$ \Big\langle $

Passé Composé, Passato Prossimo, Perfekt, Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd, Pretérito Indefinido, Simple Past, Aoristos

![]() $ \Big\rangle $

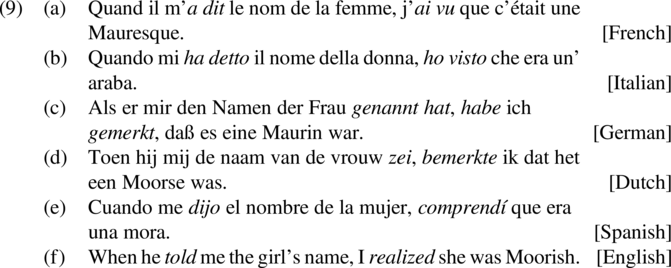

with 266 occurrences, so this is the dominant pattern for the Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd. The investigation of the datapoints in which the German translation sides with Italian in maintaining the perfect from the French original, but the Dutch translator switches to the past reveals that the Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd resists narrative use. One criterion for narrative use implies complex sentences involving a when-clause, as argued in Section 1 – see example (3). Where we find such configurations in the Camus dataset, French, Italian, and German use a perfect in both the main and the subordinate clause, but the Dutch, Spanish, and English translators switch to a past, as we see in (9):

$ \Big\rangle $

with 266 occurrences, so this is the dominant pattern for the Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd. The investigation of the datapoints in which the German translation sides with Italian in maintaining the perfect from the French original, but the Dutch translator switches to the past reveals that the Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd resists narrative use. One criterion for narrative use implies complex sentences involving a when-clause, as argued in Section 1 – see example (3). Where we find such configurations in the Camus dataset, French, Italian, and German use a perfect in both the main and the subordinate clause, but the Dutch, Spanish, and English translators switch to a past, as we see in (9):

There are four complex sentences with this pattern in our dataset. Outside of complex sentences, we took datapoints that are integrated into a sequence of events that follow each other in time to exemplify narrative use. This was consistently the case in the set of most frequent verb forms and is illustrated in (10):

In (10a)–(10c), we interpret the sequence of perfects as describing a series of events that succeed each other in time. In (10d)–(10f) the translators need a simple or perfective past to achieve temporal progress. With De Swart (Reference De Swart2007), we emphasize that the way Camus is telling the story in L’Étranger does not make the Passé Composé equivalent to the Passé Simple. The Passé Composé introduces an event in the past, that elaborates on the utterance situation (deictic orientation). The Passé Composé does not block narration as long as progress in time is induced by other means. In (10a) the series of perfects elaborates on the night of the wake, and the events are perceived by default as appearing in a natural order.

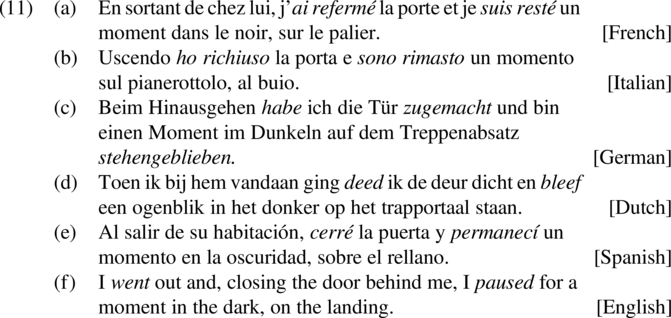

Narrative progress is often supported by lexical content. A lexical entailment is at work in (11): once the door is closed, the protagonist finds himself on the landing as the spatial result of him leaving the room and blocking out the light (Asher & Sablayrolles Reference Asher and Sablayrolles1995).

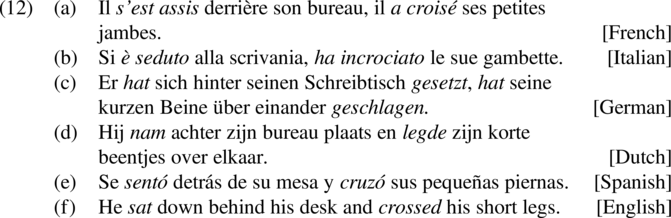

The connection between space and time leads to progress in time in configurations like (11). The sequential interpretation of (12) also relies on a lexical entailment relation: it is not until one is seated that legs can be crossed.

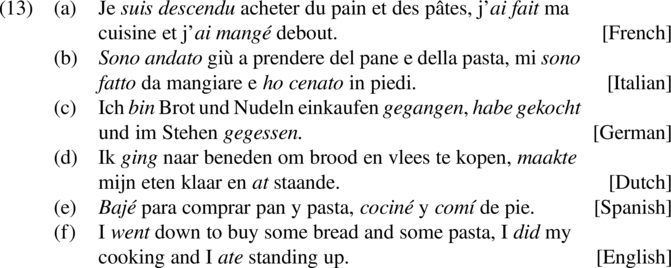

Camus also relies more broadly on world knowledge, such as scripts and scenarios. In (13), we see a dinner script at work, where shopping, cooking and eating are presented in a natural temporal order:

Although the discourse is less script-like, the natural order of events in (10) is also supported by world knowledge. In all the examples in (10)–(13) then, we do not need the verb form to actively induce a rhetorical relation of narration, because there are other lexical and pragmatic means to induce progress in time. The Italian and German translations in (10)–(13) support an extension of the observations made by De Swart (Reference De Swart2007) that French allows a perfect in these cases to Italian and German, as we expect on the basis of the literature (Bertinetto Reference Bertinetto1986; Schaden Reference Schaden2009; Dahl & Velupillai Reference Dahl, Velupillai, Dryer and Haspelmath2013). The presence of lexical and pragmatic support is not enough to license temporal sequencing with a perfect form in Dutch, Spanish, and English. The grammar of these languages bans the perfect from narrative contexts altogether, and requires the use of the simple or perfective past to introduce past events that succeed one another in time.

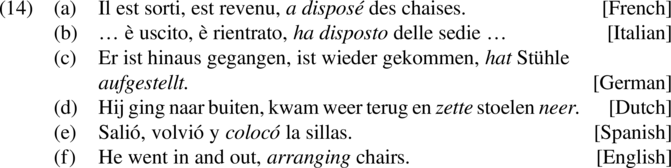

So far, we have only considered datapoints that belong to the dominant pattern for the Dutch Onvoltooid Verleden Tijd. The remaining datapoints contain various configurations of verb forms, for instance, the Present Participle in the English in (14f).

Such examples always include a German Perfekt, and they confirm that the Dutch Onvoltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd is needed for storytelling. In the context of a novel, the significant drop in numbers of perfect occurrences between German and Dutch is not surprising once we realize that the Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd resists narrative use altogether.

The Dutch/Spanish/English pattern is in line with the typological perspective (Lindstedt Reference Lindstedt and Dahl2000), as well as semantic theory (Partee Reference Partee1973, Reference Partee1984) (see Sections 1 and 2). If we take narrative use to be key, the French/Italian/German pattern supports the hypothesis that the perfect in these languages is developing into a (perfective) past (Bybee et al. Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994; Dahl & Velupillai Reference Dahl, Velupillai, Dryer and Haspelmath2013). The dataset suggests that this cannot be the full story, though, as German tolerates a narrative use for dynamic verbs, but not for stative verbs, as we saw in Section 4.1. Dynamic semantics is thus a second ingredient of the analysis of the perfect, next to lexical semantics. Section 4.3 will identify compositional semantics as a third ingredient.

4.3 From Dutch to Spanish: Past time reference

There are 39 instances of the Dutch Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd in our dataset, and 16 occurrences of the Spanish Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto. We find 15 datapoints in which the Spanish Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto pairs up with the Dutch Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd, so, barring one case of optionality in translation, the Spanish perfect domain is a proper subset of the Dutch perfect domain. In this section, we investigate the 24 contexts in which the Dutch translator follows the French original in maintaining the perfect, but the Spanish translator switches to a perfective past.

The borderline between Dutch and Spanish resides in a preference of Dutch to report past events in the Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd, as long as they do not occur in narrative contexts (Le Bruyn et al. Reference Le Bruyn, van der Klis and de Swart2019). The notion of event is here defined at the compositional level, as a quantized eventuality in the sense of Krifka (Reference Krifka, Bartsch, van Benthem and van Emde Boas1989) and De Swart (Reference De Swart1998), and thereby includes accomplishments, achievements, as well as activities bounded by a measurement expression. Bounded states are quantized in the compositional sense as well, but they are not found in the Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd, because Dutch is subject to the same constraint that bans stative verbs from appearing in the perfect as German (see Section 4.1). The Spanish translator uses the Pretérito Indefinido for past time reference, because of the hodiernal nature of the Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto (Howe Reference Howe2013), which requires the underlying event to appear in the extended now (see Section 2).

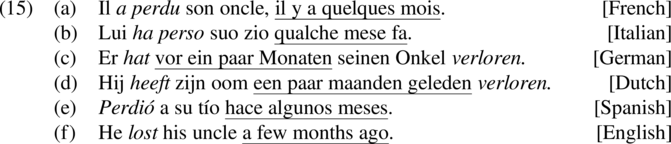

Starting with Klein (Reference Klein1992), the combination of a past time adverbial with the perfect has been a focus of attention. As outlined in Section 1, the crosslinguistic analyses by De Swart (Reference De Swart2007) and Schaden (Reference Schaden2009) have shown that Spanish shares with English the ban against past time adverbials with the perfect, whereas Dutch resembles French, Italian, and German in freely combining the perfect with past time adverbials. There are few past time locating adverbials in the dataset, but the shift from perfect in (15a)–(15d) and (16a)–(16d) to past in (15e)–(15f) and (16e)–(16f) confirms the patterns put forward in the literature concerning the crosslinguistic constraints on perfect use imposed by the past time adverbial (underlined).

Locating time adverbials interrupt narrative discourse (De Swart Reference De Swart, Bosch and Sandt1999): instead of a smooth series of events that naturally follow one another, time adverbials make us jump to a different moment in time, which creates a gap in the temporal structure. The time adverbials in (15) and (16) signal that we are not in a narrative context, and the preference to introduce events by means of a perfect leads to the use of the Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd in (15d) and (16d), whereas the hodiernal nature of the Spanish Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto leads to a shift to the Pretérito Indefinido in (15e) and (16e).

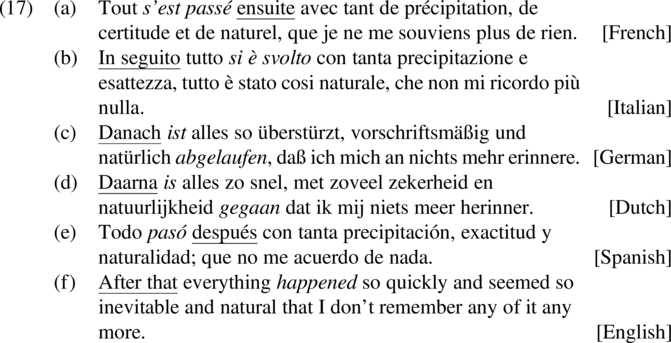

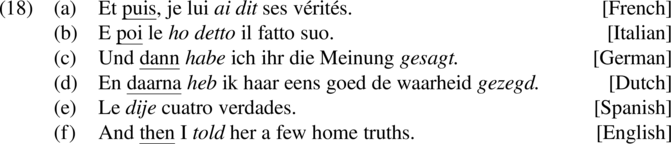

Temporal connectives fall in the same category as time adverbials as far as past time reference to events is concerned. The Dutch translator regularly opts for the Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd in the presence of a temporal connective like ensuite ‘after that’, puis ‘then’, alors ‘then’, à partir de ce moment ‘from that point on’, etc. Examples (17) and (18) illustrate (the connective is underlined).

Temporal connectives like puis create a similar break in rhetorical structure as the time adverbials in (15) and (16). They operate on the discourse level, where they impose progress in time by licensing the rhetorical relation of narration (Bras, Le Draoulec & Vieu Reference Bras, Le Draoulec, Vieu, Mellet and Vuillaume2003), so the tense form alone is not responsible for establishing narration. This activates the Dutch preference for the perfect to locate events in the past. The switch to the Pretérito Indefinido in (15)–(18) reveals that Spanish is insensitive to the distinction between narrative and non-narrative discourse, and blocks the Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto with past time reference altogether.

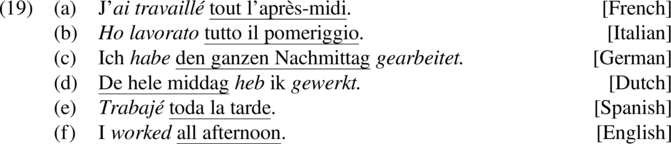

The claim that the Dutch perfect is sensitive to past time reference of events at the compositional level is confirmed by the behavior of bounded activities in the dataset. Boundedness in the sense of describing the situation as a single whole, including the beginning and the end is a familiar ingredient of the Romance perfective past (Kamp & Rohrer Reference Kamp, Rohrer, Bäuerle, Schwarze and Stechow1983; De Swart Reference De Swart1998). But boundedness has been associated with the French Passé Composé as well, for instance, by Bres (Reference Bres, Stosic, Flaux and Vet2010) and Apothéloz (Reference Apothéloz, Giancarli and Fryd2016). The analysis that Kamp et al. (Reference Kamp, Reyle and Rossdeutscher2015) formulate for the German Perfekt also relies on reference to a quantized event. The examples in (19) and (20) show that a bounded activity can be expressed by a perfect or perfective past, depending on the rules of the language-specific grammar for locating events in the past.

Example (20) is set in the context of the protagonist taking a bus from Algiers to the village of the old people’s home where his mother lived, so the activity of sleeping is here delimited in space and time through the motion context (Asher & Sablayrolles Reference Asher and Sablayrolles1995).

Boundedness is responsible for tense choice in example (21) as well.

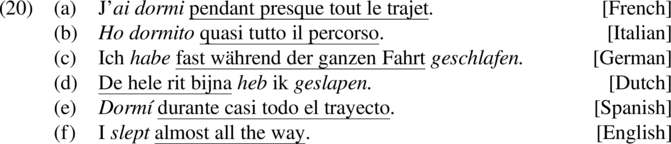

The degree quantifier beaucoup ‘a lot’ in (21a) has an object related reading in which the amount of work carried out is characterized as high (Doetjes Reference Doetjes1997). Through its measurement of the amount of work, adverbial beaucoup presents the activity of working as a delimited whole. The bounding role of the degree quantifier carries over to its translations and licenses the perfect in Italian, German, and Dutch, but not in Spanish and English, which opt for the Pretérito Indefinido and the Simple Past, notwithstanding the presence of the deictic adverbial hoy ‘today’ (see Section 4.4).

In sum, Dutch makes more frequent use of the perfect than Spanish, because, outside of narrative contexts, Dutch prefers to report past events in the perfect (Le Bruyn et al. Reference Le Bruyn, van der Klis and de Swart2019). In contrast, the Spanish Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto is hodiernal, and does not allow past time reference of events. Bounded activities with past time reference are reported in the Voltooid Tegenwoordige Tijd, so the relevant notion of event is a compositional one. These observations support the role of compositional semantics as a third ingredient in the semantics of the perfect, next to lexical semantics (Section 4.1) and dynamic semantics (Section 4.2).

4.4 From Spanish to English: Pragmatically presupposed events and deixis

The data in Sections 4.1 –4.3 lend support to the similarities between the Spanish Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto and the English Present Perfect pointed out by Schaden (Reference Schaden2009). With 16 instances of the Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto against 11 occurrences of the Present Perfect, the distribution of the English perfect is slightly more restricted in our dataset. The fact that 10 out of the 11 occurrences of the Present Perfect co-occur with the Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto confirms the subset relation in Figure 4. This subsection focuses on the contexts in which Spanish uses a perfect, but English does not.

Michaelis (Reference Michaelis1994) argues that a past event with current relevance is not enough to license the Present Perfect in English: pragmatically presupposed events cannot be reported in the Present Perfect, but require the Simple Past. So not only does the past event have to have current relevance, it has to be hearer-new. This pragmatic constraint explains why newspaper headlines as in (1d) read like ‘hot news’: reporting Malcolm X’s death in the Present Perfect draws the attention to a hearer-new event. This pragmatic constraint is at work in (22), where all languages except English use a perfect.

The motivation for the Simple Past in (22f) resides in the previous discourse. A few sentences before (22), the protagonist has entered the mortuary, in which rests his mother’s coffin, and the English translation reads as follows: ‘The lid was on, but a row of shiny screws, which hadn’t yet been tightened down, stood out against the walnut-stained wood.’ In this setting, the closed coffin is not new information, so we appeal to the constraint on pragmatically presupposed events to explain why the English translator avoids the Present Perfect. But note that the closing of the coffin took place in the last 24 hours, which supports the use of the hodiernal Spanish Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto (Howe Reference Howe2013). The example in (23) is similar:

For all languages other than English, this is a hodiernal perfect, which locates an event in the immediate vicinity of the speech time. Just like in (22f), the use of the Simple Past in (23f) is triggered by the ban against pragmatically presupposed events. In the discourse preceding (23), Meursault is pictured sitting at the window, and observing the passengers boarding the tram to the stadium. A few hours later he sees them coming back all excited and yelling things, as we see in (23). World knowledge tells us that a game always ends with a winner and a loser. The question under discussion arguably deals with the identification of the winner, rather than the fact that there is a winner. The familiarity of the event of winning in the context of a game is then responsible for the Simple Past in (23f). The contrast between (22e)/(22f) and (23e)/(23f) shows that the Spanish Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto is not incompatible with pragmatically presupposed events and reports the result of a hodiernal past event. The difference between Spanish and English thus resides in pragmatics.

The constraint on pragmatically presupposed events must be extended to account for other examples in the dataset. Adverbs referring to the extended now are in principle compatible with the English Present Perfect (e.g. Portner Reference Portner2003; see also (1c)). However, the translator prefers a Simple Past in (21f) as well as (24f), notwithstanding the presence of the deictic adverbial aujourd’hui ‘today’.

Spanish aligns with English in (21e), but not in (24e). The preference for the Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto in (24e) is in line with the hodiernal nature of the Spanish perfect, but the Pretérito Indefinido in the presence of hoy in (21e) shows that this cannot be the entire story. Michaelis’s (Reference Michaelis1994) ban on pragmatically presupposed events does not help, because there is no previous discourse: (24) is the opening sentence of the novel. The ability of the perfect to negotiate a new topic was first signaled by Nishiyama & Koenig (Reference Nishiyama and Koenig2010) and is exploited here in French and all other languages except English to set the stage for the story. According to Michaelis (Reference Michaelis1994), English speakers sometimes prefer a Simple Past in non-anaphoric contexts where a Present Perfect would also be possible. Note further that the English translation has a slightly different information structure, which is signaled by the change in word order between the French original and the English translation: the sentence-initial position of aujourd’hui makes today the temporal frame for the main clause event (Hinrichs Reference Hinrichs1986). The postposition of the adverbial today in the English translation turns it into a modifier of the main clause event, rather than a temporal frame (De Swart Reference De Swart, Bosch and Sandt1999). The subsequent sentence questions the location in time of the event of dying, which makes it possible to accommodate the event of dying on introduction. The emphasis is placed on the location in time of the dying event, rather than the current relevance of the result state of the passed away mother.

The appeal to presupposition accommodation under an extended ban against pragmatically presupposed events helps to explain the use of the Simple Past in the English translation of (24). An extended interpretation of Michaelis’s (Reference Michaelis1994) pragmatic constraint is not always easy to come by, though. In example (25) all languages including Spanish maintain the perfect in the presence of a deictic adverbial like ce mois-ci ‘this month’, but the English translator switches to a Simple Past.

The interval denoted by the deictic time adverbial in (25) is easily perceived as placed in an extended now. The continuation of the sentence in the present emphasizes the current relevance of the past event as indicative of the speaker’s generosity. In (25a)–(25e), this is enough to license the use of a perfect, but the Simple Past in (25f) shifts the focus to the event of buying the outfit rather than the addressee having it.

A full account of the pragmatic differences between the Spanish Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto and the English Present Perfect is beyond the scope of this paper, but the examples discussed indicate that deixis and information structure at the discourse level are crucial to a better understanding of the differences between the two languages. Pragmatics thus constitutes the fourth ingredient of a crosslinguistically robust semantics of the perfect.

4.5 Classic perfect configurations and the more restricted perfect use in Greek

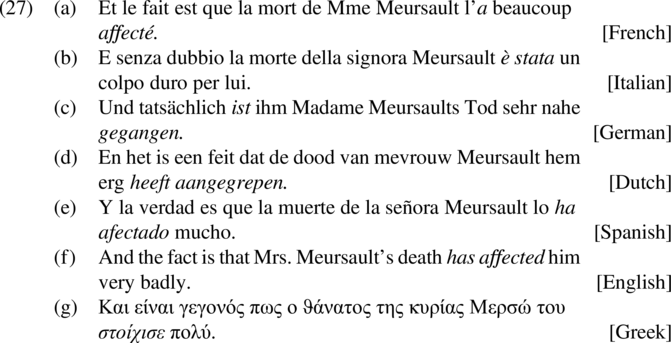

The investigation of the 11 datapoints in which the English translator opts for the Present Perfect shows that they instantiate the ‘classic’ configurations familiar from the literature discussed in Sections 1 and 2, and illustrated in (1). We find the resultative perfect in (26) and (27).

In examples (26) and (27), the current relevance of the result state licenses the perfect in all languages except for Greek, which uses an Aoristos in both (26g) and (27g).

Another classic configuration is the existential perfect, especially with negation (see e.g. Iatridou Reference Iatridou2014). The Greek translation in (28g) provides the one and only example of the Parakimenos in our dataset.

We also find an existential perfect in combination with a negative universal quantifier (jamais ‘never’ in (29)); note that Greek uses a past perfect here.

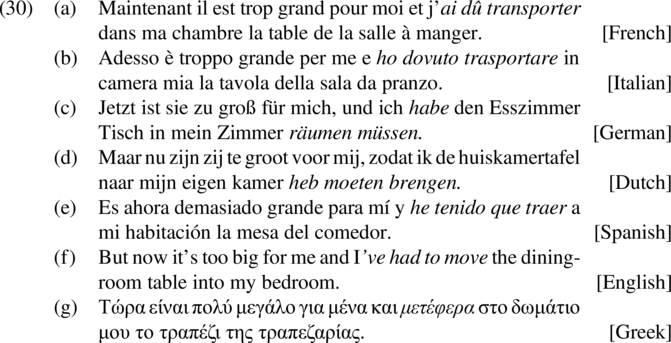

Nishiyama & Koenig (Reference Nishiyama and Koenig2010) draw attention to instances of inverse causality, where the past event does not cause the resultative state, but the state that currently holds is the reason why the past action is taken. Example (30) instantiates this configuration in L’Étranger.

Sentence (30a) in the Passé Composé conveys that the protagonist moved the table into the bedroom because the apartment (the referent of the pronoun il) was too big for a single person. The translations in (30b)–(30f) confirm that all the languages in our study use a perfect to convey inverse causality, except for Greek, which uses an Aoristos in (30g).

We conclude that the ‘classic’ perfect readings familiar from the literature on the English Present Perfect are also found in the other languages in our dataset. Greek is the only exception, with a clearly more restricted distribution of the Parakimenos, but we need a larger dataset to provide a linguistic analysis of the Greek perfect (see Askitidis Reference Askitidis2019).

4.6 Linguistic interpretation of the subset relation

Most of the theoretical literature focus on the ‘classic’ perfect readings, but we think that languages that display a narrower distribution (such as Greek) as well as languages with a more liberal perfect use (such as French and Italian) should play a role in a crosslinguistically validated analysis of the perfect. In the competition between perfect and past, we should not forget the intermediate position occupied by languages such as German, Dutch, and Spanish either. In this section, we determined the language-specific constraints that underlie the division of labor between perfect and past. The first line in (31) shows the subset relation between languages in terms of perfect use. The second line shows the constraints that come into play and in turn portrays the implicational hierarchy of perfect use that arises from this paper.

If we were dealing with a dichotomy between past and perfect-oriented languages, we would expect a single linguistic criterion to drive the opposition. In contrast, (31) indicates that the grammar of the perfect is sensitive to lexical semantics (stative vs. dynamic verbs), compositional semantics (boundedness), dynamic semantics (narration), and pragmatics (deixis and information structure). The fact that different factors come into play in the crosslinguistic grammar of the perfect supports the scalar approach to the perfect-past competition we established in Section 3.

5. Conclusion

The western European perfect is subject to substantial crosslinguistic variation. To do full justice to it, we let go of the idea that past tenses should either qualify as perfects or (perfective) pasts and assume a purely form-based perspective, allowing variation in distribution to guide our analysis of the configuration have/be + past participle. We introduced and showcased Translation Mining, a software suite combining a parallel corpus database with annotation and analysis tools. We used Translation Mining to map out and probe the variation in a data-driven way by comparing the use of the perfect through the French novel L’Étranger and its translations in Italian, German, Dutch, Spanish, English, and Greek. We followed the literature in assuming that French has the most liberal perfect use – championed by Camus in L’Étranger – and tracked the restrictions in the other languages. Even though our dataset did not allow us to address relevant dimensions of variation for Italian and Greek, our data are in line with the intuitions in the literature about Italian patterning with French and Greek having the most restricted use of the perfect. The distribution of German, Dutch, Spanish, and English perfects reveals that they all take different hierarchically ordered intermediate positions between the liberal French and Italian perfects and the restricted Greek perfect. We argued that the differences in distribution correlate with differences in the grammar of the perfect and identified four crucial dimensions: lexical semantics (stativity vs. dynamicity), compositional semantics (past time reference of the underlying event), dynamic semantics (narrative or non-narrative contexts), and pragmatics (deixis, information structure). The variation that we have found confirms the findings of studies focusing on individual languages or on restricted numbers of languages, and it allows us to establish their relevance from a crosslinguistic perspective, bearing witness to a division of labor between the perfect and (perfective) past that is better conceptualized as a competition than as a strict dichotomy.

The dataset on which our conclusions are based consists of occurrences of the French Passé Composé and their translations. We did not extract all perfects in all languages, so, as correctly pointed out by one of the reviewers, we cannot exclude the possibility that the translators introduced a perfect in a context where Camus used a verb form other than the Passé Composé. Space restrictions prevent the exploration of this possibility in the current paper, but in follow-up research, we analyze an extended dataset that includes all the verb forms in Chapter 1 of L’Étranger. Van der Klis, Le Bruyn & De Swart (Reference Van der Klis, Le Bruyn and de Swart2021) show that the extended dataset upholds the subset relation and thereby confirm the robustness of the insights achieved in this paper.

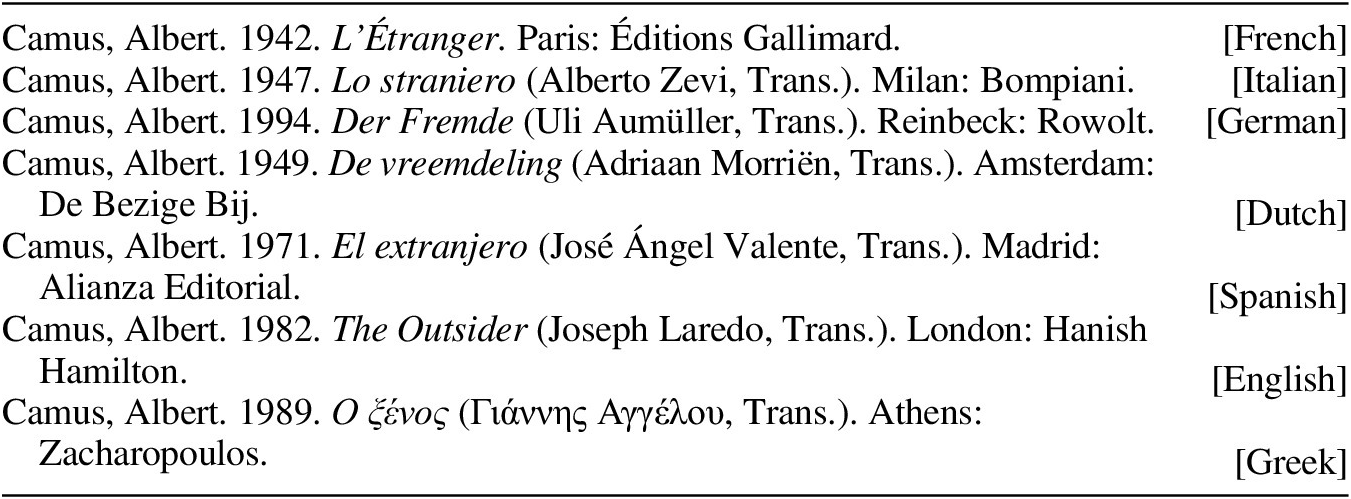

Appendix A: Bibliographical details of the source text and its translations