Abstract

In the race to the South Pole, Roald Amundsen’s expedition covered an equal distance each day, irrespective of weather conditions, while Scott’s pace was erratic. Amundsen won the race and returned without loss of life, while Scott and his men died. In the context of firm growth, the Amundsen hypothesis suggests that smoother growth paths are associated with better performance in subsequent periods. We develop a new method to investigate how firms’ sales growth deviates from their long-run average growth path. Our baseline results suggest that growth path volatility is associated with higher growth of sales and profits, but also with higher exit rates. However, this result is driven by firms with negative growth rates. For positive-growth firms, volatility is negatively associated with both sales growth and survival, providing nuanced support for the Amundsen hypothesis.

Plain English Summary

In the race to the South Pole, Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott adopted different strategies that resulted in victory for Amundsen and death for Scott. Amundsen’s approach was to consistently pace his team (to cover a fixed and equal distance each day), while Scott sought to cover as much distance as possible each day. In the context of firm growth, this relates to the tradeoff between steady growth (low volatility in growth rates) and growing as fast as possible in each period (potentially leading to high volatility in growth rates). We develop a new set of indicators for quantifying firms’ growth paths, observing that growth path volatility in general is associated with higher growth of sales and profits, but also with higher death rates. This result is driven by firms with negative sales growth, however. Like Amundsen, it seems beneficial for firms with positive sales growth to pace themselves to increase their subsequent growth and likelihood of survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Amundsen and Scott’s preparations and race to the South Pole is excellently covered in Roland Huntford’s novel The Last Place on Earth: Scott and Amundsen’s Race to the South Pole (Huntford, 1999).

While we concur that the Amundsen-Scott case is an interesting metaphor for starting discussions about firm growth paths, of course, we do not claim the metaphor is perfect.

It is also possible that more volatile growth paths are signs that the firm is governed by managers that are less able to plan ahead, i.e., that volatility rather is a consequence of bad planning.

As is often done in the empirical literature, we group together voluntary liquidations with bankruptcies, because they are both instances of firm death (Coad, 2014).

See, for example, Baù et al. (2019) for a recent concise discussion.

Considering that firm growth rates lack persistence and that the within-variation in firm growth rates is higher than the between-variation in growth rates (Geroski & Gugler, 2004), we follow previous literature on firm growth (e.g. Coad, 2010) and do not include time-invariant firm-specific fixed effects in our regressions.

For example, industry-specific fixed effects can alleviate possible issues of industry-specific degrees of volatility of annual growth rates. However, presumably the main type of industry-specific variations in demand occur at a seasonal frequency, not at the level of annual growth rates, and like the vast majority of firm growth research, we cannot control for within-the-year seasonal variations in demand. Another use of industry-specific fixed effects is to control for potential differences in the capital intensity of growth rates that may vary across industries.

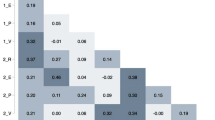

A first reason for our present unconcern about multicollinearity is that we have a large number of observations (O’Brien, 2007). Furthermore, a correlation matrix (see table 6 in the appendix) allays fears about excessive pairwise correlations between variables. As an extra check, Online Appendix OSM-3 verifies the stability of the coefficients across specifications as variable blocks are introduced stepwise.

See, for example, the survey of R2 statistics obtained from growth rate regressions in Coad 2009, Table 7.1. Furthermore, we expect a low R2 in our estimations, given that our sample covers a large number of small firms (whose growth rates are more erratic than for small samples of large firms).

Note however that our estimates in Table 4 Column 3 suggest that higher initial size is positively associated with exit, which goes against many previous results. The usual interpretation of the size-exit relationship may not hold in Table 3 Column 3 because exit in (t:t + 3) is conditional upon surviving all of the growth path period (t-4:t), and this may select out small short-lived firms. In our data, the simple correlation between exit and once-lagged log size is indeed negative. Also, our regression results for this coefficient remain similar after a stepwise introduction of covariates. We therefore advise caution when interpreting the relationship between initial size and subsequent exit, and we do not suggest a naive interpretation that larger firms have higher exit rates.

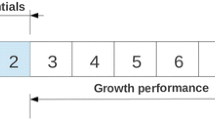

The figures correspond to the relationship between growth path volatility (t-4:t) over different percentile groups of the Average growth rate variable and sales growth, profit growth, and firm exit over the subsequent period (t:t + 3).

Essentially, this allows the “effect” of Area to vary, depending on where in the distribution of Average growth rate a firm is located. We include interaction effect between Area and a set of dummy variables that corresponds to the percentile groups of the Average growth rate variable. The point estimates, i.e. the marginal effects, is therefore given by dy/dx = a + b(i) * p(i)*(Average growth rate) where “i” corresponds to the different percentile groups “5 < 10, …, > 95”. The estimate for “a” corresponds to the result for p(< 5), which is used as the reference group. The effects of subsequent groups such as p(5 < 10) is hence given by “a + b(5 < 10)”.

These results are omitted in order to save space, but are available from the authors upon request.

References

Acs Z., Parsons W., Tracy S., (2008). High impact firms: Gazelles revisited. SBA working paper No. 328, June.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2008). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press.

Arora, A., & Nandkumar, A. (2011). Cash-out or flameout! Opportunity cost and entrepreneurial strategy: Theory, and evidence from the information security industry. Management Science, 57(10), 1844–1860.

Bamford, C. E., Dean, T. J., & Douglas, T. J. (2004). The temporal nature of growth determinants in new bank foundings: Implications for new venture research design. Journal of Business Venturing, 19, 899–919.

Baù, M., Chirico, F., Pittino, D., Backman, M., & Klaesson, J. (2019). Roots to grow: Family firms and local embeddedness in rural and urban contexts. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(2), 360–385.

Bernard, A. B., Boler, E. A., Massari, R., Reyes, J. D., & Taglioni, D. (2017). Exporter dynamics and partial-year effects. American Economic Review, 107(10), 3211–3228.

Bhide, A. (1992). Bootstrap finance: The art of start-ups. Harvard Business Review, 70(6), 109–117.

Bottazzi, G., & Secchi, A. (2006). Explaining the distribution of firm growth rates. Rand Journal of Economics, 37(2), 235–256.

Brännback, M., Carsrud, A. L., Kiviluoto, N. (2014). Understanding the myth of high growth firms: The theory of the greater fool. Springer Science & Business Media. Springer

Bloom, N. (2014). Fluctuations in uncertainty. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(2), 153–176.

Bo, H. (2001). Volatility of sales, expectation errors, and inventory investment: Firm level evidence. International Journal of Production Economics, 72(3), 273–283.

Brenner, T., & Schimke, A. (2015). Growth development paths of firms – A study of smaller businesses. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(2), 539–557.

Brynjolfsson, E., Rock, D., & Syverson, C. (2021). The productivity J-curve: How intangibles complement general purpose technologies. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 13(1), 333–372.

Capasso, M., Cefis, E., & Frenken, K. (2014). On the existence of persistently outperforming firms. Industrial and Corporate Change, 23(4), 997–1036.

Carow, K., Heron, R., & Saxton, T. (2004). Do early birds get the returns? An empirical investigation of early-mover advantages in acquisitions. Strategic Management Journal, 25(6), 563–585.

Coad, A. (2007). A closer look at serial growth rate correlation. Review of Industrial Organization, 31, 69–82.

Coad, A. (2009). The growth of firms: A survey of theories and empirical evidence. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Coad, A. (2010). Exploring the processes of firm growth: Evidence from a vector autoregression. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(6), 1677–1703.

Coad, A., Daunfeldt, S. O., Hölzl, W., Johansson, D., & Nightingale, P. (2014). High-growth firms: Introduction to the special section. Industrial and Corporate Change, 23(1), 91–112.

Coad, A., Daunfeldt, S. O., & Halvarsson, D. (2018). Bursting into life: Firm growth and growth persistence by age. Small Business Economics, 50(1), 55–75.

Coad, A., Frankish, J., Roberts, R., & Storey, D. (2013). Growth paths and survival chances: An application of Gambler’s ruin theory. Journal of Business Venturing, 28, 615–632.

Coad, A., Frankish, J. S., Roberts, R. G., & Storey, D. J. (2015). Are firm growth paths random? A reply to “Firm growth and the illusion of randomness.” Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 3, 5–8.

Coad, A., Frankish, J. S., & Storey, D. J. (2020). Too fast to live? Effects of growth on survival across the growth distribution. Journal of Small Business Management, 58(3), 544–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2019.1662265

Coad, A., & Planck, M. (2012). Firms as bundles of discrete resources – Towards an explanation of the exponential distribution of firm growth rates. Eastern Economic Journal, 38, 189–209.

Collins, J., & Hansen, M. T. (2011). Great by choice: Uncertainty, chaos and luck-why some thrive despite them all. Random House.

Cowling, M. (2004). The growth-profit nexus. Small Business Economics, 22(1), 1–9.

Cowling, M., & Liu, W. (2011). ASBS barometer report on business growth, access to finance, and performance outcomes in the recession. Department for Business, Innovation and Skills.

Cowling, M., Liu, W., Yue, W., & Do, H. (2019). Market consolidation, market growth, or new market development? Owner, firm, and competitive determinants.International Review of Entrepreneurship, 17(1)

Cowling, M., & Nadeem, S. P. (2020). Entrepreneurial firms: With whom do they compete, and where? Review of Industrial Organization, 57(3), 559–577.

Cruz, M., Bussolo, M., & Iacovone, L. (2018). Organizing knowledge to compete: Impacts of capacity building programs on firm organization. Journal of International Economics, 111, 1–20.

Davidsson, P., Steffens, P., & Fitzsimmons, J. (2009). Growing profitable or growing from profits: Putting the horse in front of the cart? Journal of Business Venturing, 24(4), 388–406.

Daunfeldt, S. O., & Halvarsson, D. (2015). Are high-growth firms one-hit wonders? Evidence from Sweden. Small Business Economics, 44(2), 361–383.

Delmar, F., Davidsson, P., & Gartner, W. B. (2003). Arriving at the high-growth firm. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 189–216.

Derbyshire, J., & Garnsey, E. (2014). Firm growth and the illusion of randomness. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 1, 8–11.

Doms, M., & Dunne, T. (1998). Capital adjustment patterns in manufacturing plants. Review of Economic Dynamics, 1(2), 409–429.

Garnsey, E., & Heffernan, P. (2005). Growth setbacks in new firms. Futures, 37(7), 675–697.

Garnsey, E., Stam, E., & Heffernan, P. (2006). New firm growth: Exploring processes and paths. Industry and Innovation, 13(1), 1–20.

Geroski, P., & Gugler, K. (2004). Corporate growth convergence in Europe. Oxford Economic Papers, 56, 597–620.

Gilbert, R. J., Newbery, D. M. (1982). Preemptive patenting and the persistence of monopoly. The American Economic Review, 514–526.

Hamermesh, D. S., & Pfann, G. A. (1996). Adjustment costs in factor demand. Journal of Economic Literature, 34(3), 1264–1292.

Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1977). The population ecology of organizations. American Journal of Sociology, 82(5), 929–964.

Henrekson, M., & Johansson, D. (2010). Gazelles as job creators: A survey and interpretation of the evidence. Small Business Economics, 35(2), 227–244.

Lieberman, M. B., & Montgomery, D. B. (1988). First-mover advantages. Strategic Management Journal, 9(S1), 41–58.

Lockett, A., Wiklund, J., Davidsson, P., & Girma, S. (2011). Organic and acquisitive growth: re-examining, testing and extending Penrose’s growth theory. Journal of Management Studies, 48(1), 48–74.

Lundmark E., Coad A., Frankish J.S., Storey D.J. (2020). The liability of volatility and how it changes over time among new ventures. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, in press.

Marris, R. (1964). The Economic Theory of Managerial Capitalism. Macmillan.

McKelvie, A., & Wiklund, J. (2010). Advancing firm growth research: A focus on growth mode instead of growth rate. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(2), 261–288.

McMahon, R. G. P. (2001). Deriving an empirical development taxonomy for manufacturing SMEs using data from Australia’s Business Longitudinal Survey. Small Business Economics, 17, 197–212.

O’Brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity, 41(5), 673–690.

Paulsen, N., Callan, V. J., Grice, T. A., Rooney, D., Gallois, C., Jones, E., Jimmieson, N. L., & Bordia, P. (2005). Job uncertainty and personal control during downsizing: A comparison of survivors and victims. Human Relations, 58(4), 463–496.

Penrose, E. T. (1959). The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell.

Pollard, T. M. (2001). Changes in mental well-being, blood pressure and total cholesterol levels during workplace reorganization: The impact of uncertainty. Work & Stress, 15(1), 14–28.

Spence, A. M. (1981). The learning curve and competition. The Bell Journal of Economics, 49–70.

Stam, E., & Wennberg, K. (2009). The roles of R&D in new firm growth. Small Business Economics, 33, 77–89.

Stephan, U. (2018). Entrepreneurs’ mental health and well-being: A review and research agenda. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(3), 290–322.

Törnqvist, L., Vartia, P., & Vartia, Y. O. (1985). How should relative changes be measured? The American Statistician, 39(1), 43–46.

Wernerfelt, B. (1986). A special case of dynamic pricing policy. Management Science, 32(12), 1562–1566.

Wernerfelt, B. (1988). General equilibrium with real time search in labor and product markets. Journal of Political Economy, 96(4), 821–831.

Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2003). Aspiring for, and achieving growth: The moderating role of resources and opportunities. Journal of Management Studies, 40(8), 1919–1941.

Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. A. (2011). Where to from here? EO-as-experimentation, failure, and distribution of outcomes. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(5), 925–946.

Zhou, H., & van der Zwan, P. (2019). Is there a risk of growing fast? The relationship between organic employment growth and firm exit. Industrial and Corporate Change, forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtz006

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix 1 details on the sample and variables

Appendix 1 details on the sample and variables

We also test if our results are robust to commonly used growth dispersion measures, such as the absolute min–max growth difference (AMM). The AMM measure is calculated by first ranking a firm’s growth rates in order of size and then calculating the absolute difference between the firm’s largest growth rate and the smallest growth rate. More formally, if \(\left|{s}^{\mathrm{max}}\right|=\mathrm{max}{\left(\left|\mathrm{ln}\frac{S\left(t+1\right)}{S\left(t\right)}\right|\right)}_{t=0}^{T}\) and \(\left|{s}^{\mathrm{min}}\right|=\mathrm{min}{\left(\left|\mathrm{ln}\frac{S\left(t+1\right)}{S\left(t\right)}\right|\right)}_{t=0}^{T}\) corresponds to the largest and smallest absolute growth rates over the sequence of growth rates, the AMM measure can be defined as:

Finally, in order to compare our results with a traditional volatility measure, we have also done all estimations using the standard deviation (SD) as our growth dispersion measure.

All growth dispersion measures that are used in the paper are normalized to have mean zero, and a standard deviation of one. To calculate \(Area\) and \(AMM\), we use consecutive periods, each with \(T=4\). The outcome measures, we consider is the future growth rate of \(\mathrm{ln}\frac{S\left(T+k\right)}{S\left(T\right)}\) with \(k=\mathrm{1,2}\) and \(3\).

The correlation between our new indicator of growth dispersion and the more traditional ones are presented in Table 1

Our main results remain qualitatively similar when using the alternative growth dispersion measures. Note, however, that these alternative growth dispersion measures cannot be used to categorize firms into different growth types (see Table 5).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coad, A., Daunfeldt, SO. & Halvarsson, D. Amundsen versus Scott: are growth paths related to firm performance?. Small Bus Econ 59, 593–610 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00552-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00552-y