Abstract

A recent increase in the literature regarding the evidence base for clozapine has made it increasingly difficult for clinicians to judge “best evidence” for clozapine use. As such, we aimed at elucidating the state-of-the-art for clozapine with regard to efficacy, effectiveness, tolerability, and management of clozapine and clozapine-related adverse events in neuropsychiatric disorders. We conducted a systematic PRISMA-conforming quantitative meta-review of available meta-analytic evidence regarding clozapine use. Primary outcome effect sizes were extracted and transformed into relative risk ratios (RR) and standardized mean differences (SMD). The methodological quality of meta-analyses was assessed using the AMSTAR-2 checklist. Of the 112 meta-analyses included in our review, 61 (54.5%) had an overall high methodological quality according to AMSTAR-2. Clozapine appears to have superior effects on positive, negative, and overall symptoms and relapse rates in schizophrenia (treatment-resistant and non-treatment-resistant subpopulations) compared to first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) and to pooled FGAs/second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) in treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS). Despite an unfavorable metabolic and hematological adverse-event profile compared to other antipsychotics, hospitalization, mortality and all-cause discontinuation (ACD) rates of clozapine surprisingly show a pattern of superiority. Our meta-review outlines the superior overall efficacy of clozapine compared to FGAs and most other SGAs in schizophrenia and suggests beneficial efficacy outcomes in bipolar disorder and Parkinson’s disease psychosis (PDP). More clinical studies and subsequent meta-analyses are needed beyond the application of clozapine in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and future studies should be directed into multidimensional clozapine side-effect management to foster evidence and to inform future guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Clozapine—considered the most effective antipsychotic—was introduced in the early 1970s for the treatment of schizophrenia. First, clozapine was believed to have not only superior efficacy but also to have overall better tolerability compared to first-generation antipsychotics (FGA) due to a low risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). However, in 1975, clozapine was voluntarily withdrawn since 17 out of 2660 (0.7%) patients treated with clozapine in Finland developed agranulocytosis and eight patients subsequently died [1]. In 1988, Kane et al. confirmed clozapine’s safety and superiority vs. chlorpromazine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS) [2], and subsequently, the Federal Drug Agency (FDA) and other health authorities approved its re-introduction for the indication of TRS with regular hematological monitoring.

Evidence-based treatment guidelines for the management of difficult-to-treat schizophrenia currently recommend clozapine [3,4,5]. Nevertheless, definitions of TRS, typically involving two failed trials of different non-clozapine antipsychotics, differ significantly across guidelines [6] as do criteria for TRS in clinical trials: if TRS is operationalized at all, it differs in up to 95% of trials [7]. A lack of consensus is also represented in the extent and frequency of mandatory safety monitoring procedures beyond hematological monitoring during clozapine treatment according to the respective national regulations [6]. Further indications or recommendations, when clozapine can be applied in clinical practice, are poorly harmonized: in certain European countries, (e.g. Germany, the Netherlands) clozapine is indicated for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease psychosis (PDP), whereas in the US it was given a Level B recommendation by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) for this indication. Furthermore, the FDA approved clozapine as the first agent indicated for suicidality in people with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Furthermore, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommends (1B) that patients with TRS be treated with clozapine and recommends (1B) patients with schizophrenia be treated with clozapine if the risk for suicide attempts or suicide remains substantial despite other treatments and suggests (2C) that patients with schizophrenia be treated with clozapine if the risk for aggressive behavior remains substantial despite other treatments [8]. Of note, clozapine is recommended in some clinical guidelines for treatment-refractory bipolar disorder [9] with an uncertain body of evidence suggesting beneficial effects on e.g. mania, depression, rapid cycling and psychotic symptoms [10].

Even though clozapine is considered one of the most effective medications and is listed in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines [11], there is frequently a delay in clozapine initiation, leading to poorer mental health and functional outcomes [10, 12], preceded by attempts of polypharmacy treatment without evidence for effectiveness [13].

The scientific literature regarding clozapine is vastly increasing and evidence-based psychiatry might help clinicians to judge the best evidence and decision-makers and clinicians are overstrained by the number of individual studies, reviews and meta-analyses [14].

Thus, with our quantitative meta-review of meta-analyses we aimed at elucidating the state-of-the-art of efficacy, effectiveness, tolerability and management of clozapine and clozapine-related adverse-events in order to synthesize evidence, provide orientation for decision-makers and clinicians and identify treatment gaps for future research.

Methods

Information sources and search

This meta-review was pre-registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020164135). Following the structure of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10 WHO Version, 2015), we searched the PubMed/MEDLINE database and the EMBASE databases using the following search terms with limitation to systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses: “clozapine” OR “leponex” OR “clozaril”. The literature searches and selection were independently performed by EW and PiyF and validated by AH. The titles and the abstracts of each citation were screened manually, and the full text of each potentially relevant citation was retrieved for detailed review. Pharmacological or non-pharmacological clozapine augmentation/combination strategies with the purpose of clinical improvement were excluded a priori since evidence in this field was already meta-reviewed by members of our group [15]. Furthermore, studies focusing on genetics and/or pharmacogenetics, brain-imaging studies, cost-effectiveness studies, and animal studies were excluded. Three publications [16,17,18] were added by hand since two were published after the search period [16, 18] and one included sub-analyses for a new domain [17] (see Fig. 1).

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were all meta-analyses published in English between January 1, 1970, and December 19, 2019 (PubMed) and 1970–2019 (EMBASE) with quantitative data of people treated with clozapine alone or clozapine vs any control (clozapine, placebo, or non-clozapine antipsychotics). The major exclusion criteria were the absence of clozapine-specific meta-analytic data. We extracted clozapine-specific meta-analytic data on effectiveness, efficacy, and tolerability of clozapine, management of clozapine, and clozapine-related adverse events. The applied search strategy according to The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [19] is shown in Fig. 1.

Data collection process

After full-text review, one researcher (EW) extracted quantitative data from pairwise meta-analyses with validation by a second researcher (PiyF). Network meta-analytic data was extracted if pairwise analyses were presented. If standardized mean difference (SMD), mean difference (MD), risk difference (RD) > 0 demonstrated a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events) then the direction ‘clozapine’, was extracted, however, if <0 then the direction “control” was extracted. If RR, odds ratio (OR), hazard ratio (HR) > 1 meant a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events/dropouts) then the direction ‘clozapine’, otherwise ‘control’, was extracted. Furthermore, we grouped outcomes into short-term (up to 12 weeks), medium-term (13–26 weeks), and long-term (over 26 weeks).

Data transformation

The data transformation process was conducted by two authors (EW and SS) with validation by a third author (SL) using R statistical software version 4.0.3 [20] and the package tidyverse version 1.1.3 [21] OR and RD were transformed to RR [22] while HR and incidence rate ratio (IRR) was used as RR. MD was transformed into SMD [23], and in case the total number of participants in the control and experimental group were not given, equal groups were assumed. A beneficial outcome for the experimental intervention was represented with SMD > 0 or OR > 1, and minus or inverse transformations were applied whenever the opposite direction was reported. Due to limited data, adverse events of clozapine add-on strategies were not able to be included in the analyses.

Endpoints

Endpoints were defined as (1) efficacy of clozapine (SMD and RR), (2) tolerability/adverse events of clozapine (SMD and RR), and (3) efficacy of add-on strategies to improve clozapine-related adverse events (SMD and RR).

Methodological quality assessment of included meta-analyses

The Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR-2) checklist [24] was used independently by two reviewers (EW, PiyF). Disagreements were solved by consensus with a third reviewer (AH). Then, meta-analyses were categorized into different domains according to their objectives, taking into consideration participant characteristics, comparisons, and outcomes. In case of an overlap of two domains within one meta-analysis, categorization was performed with a primary focus on population characteristics (e.g. first-episode schizophrenia) before outcomes (e.g. metabolic outcomes) (see Table 1).

Results

1078 records were identified and the publications were added manually [16,17,18]. After the removal of duplicates, 959 records remained. A total of 767 records were excluded on the title/abstract level. The remaining 192 publications were retrieved as full texts and were further assessed for eligibility. From these, 112 records were included in this meta-review. 80 records were excluded as they met at least one of the exclusion criteria on full text-level (see Fig. 1). Since no evidence is considered an important finding according to the Cochrane Handbook [25], two clozapine-specific Cochrane Database reviews/meta-analyses that yielded no quantitative data due to a lack of relevant studies [26, 27], were included in our umbrella review.

Study characteristics/AMSTAR ratings

From the 112 included meta-analyses [10, 16,17,18, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131] a majority reported data on clozapine as subgroup or sensitivity analysis, whereas 34 exclusively targeted populations of clozapine users (see Table 1). According to AMSTAR-2, 61 (54.5%) meta-analyses were rated as high-quality. A description of the results of each meta-analysis along with their overall quality is presented in the Supplementary Tables (see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, https://github.com/sksiafis/clozapine_meta_review).

Endpoints

Efficacy of clozapine (SMD and RR)

Positive symptoms in schizophrenia

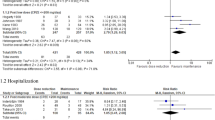

Clozapine appears to be superior to FGAs in RCTs (short, medium, and long-term) with small to medium effects sizes [48, 79, 125]. Clozapine appears to be superior to risperidone in Japanese populations with a medium effect size [29, 31]. For TRS, clozapine appears to be not significantly superior to pooled SGAs in observational studies [82], and not significantly superior to other single SGAs [100] in RCTs. When FGAs/SGAs are pooled, clozapine appears to be superior in improving positive symptoms in RCTs in TRS with a small effect size [106] see Fig. 2A).

A Positive symptoms. FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. Abbreviated study descriptions: Leucht et al., 2009a [76], Leucht et al., 2009b [76], Leucht et al., 2009c [79]. For continuous outcomes, SMD > 0 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events. B Negative symptoms. FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. Abbreviated study descriptions: Leucht et al., 2009a [76], Leucht et al., 2009b [76], Leucht et al., 2009c [79]. For continuous outcomes, SMD > 0 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events. C Overall symptoms. FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. Abbreviated study descriptions: Leucht et al., 2009a [76], Leucht et al., 2009b [76], Leucht et al., 2009c [79]. For continuous outcomes, SMD > 0 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events. D Global impression. FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. For continuous outcomes, SMD > 0 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events. E Quality of life and global functioning. CGAS Children’s Global Assessment Scale, FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, MLDL Münchner Lebensqualitäts–Dimensionen–Liste, n number of participants, RCT randomized controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic, SWN Subjective Wellbeing under Neuroleptics Scale, WHO-QOL: WHO-Quality of life. For continuous outcomes, SMD > 0 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events. F Other symptoms (cognition, hostility, depression) as a continuous outcome. BPRS Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, CGI clinical global impressions, FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, PANSS Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, RCT randomized controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. For continuous outcomes, SMD > 0 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events. G Response to treatment. FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. For dichotomous outcomes, RR > 1 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events/dropouts). H Relapse. FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. abbreviated study descriptions: Leucht et al., 2009a [76], Leucht et al., 2009b [76], Leucht et al., 2009c [79]. For dichotomous outcomes, RR > 1 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events/dropouts). I Dropouts. FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. For dichotomous outcomes, RR > 1 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events/dropouts).

Negative symptoms in schizophrenia

Clozapine is not superior to SGAs in observational studies [82], but to most FGAs in RCTs with both small and large effect sizes [48, 79, 125]—except short-term data vs chlorpromazine [100, 128]. There is conflicting evidence regarding the superiority of clozapine vs. pooled SGAs in TRS [100, 106] and clozapine appears inferior to quetiapine (short-term, only 2 studies with n total = 142) with medium effect sizes [29, 30, 76] and aripiprazole medium-term in RCTs with a small effect size [61] (see Fig. 2B).

Overall symptoms in schizophrenia

Clozapine appears to be superior to placebo in short-term RCTs with large effect sizes [76, 78], superior to FGAs in RCTs with small to medium effect sizes [44, 48, 79, 99, 125] and to SGAs in observational studies with a small effect size [82] and quetiapine in long-term RCTs with a large effect size [65]. For TRS, clozapine appears to be superior vs. CPZ with a medium effect size [100], superior vs. mixed FGAs/SGAs in RCTs with small effect sizes [85, 106], but the evidence is suggestive that clozapine is not superior vs. other antipsychotics in long-term RCTs [100, 106]. (see Fig. 2C).

Other efficacy measures in schizophrenia

Clozapine has a favorable profile in terms of dropout due to inefficacy compared to placebo with a large effect size [57] and to CPZ with a medium effect size [99] and SGAs, namely risperidone with medium effect sizes [29, 65, 67, 70, 76] and in terms of ACD rates compared to FGAs with small effect sizes [48, 99, 125], grouped SGAs in observational studies with a small effect size [82] and some single SGAs (e.g. risperidone and quetiapine) with small effect sizes [65] (see Fig. 2I).

With regard to relapse, clozapine appears to be superior to FGAs long-term [79, 125], but evidence from meta-analyses is inconsistent [64] (see Fig. 2H). With regard to response, clozapine appears to be superior to placebo with large effect sizes [57, 66], superior to FGAs short-term with small effect sizes [48, 99, 106, 125], but not superior to single SGAs (e.g. quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine) [29, 30, 61, 67, 70, 122] (see Fig. 2G). As a second-line agent, clozapine appears to be superior to risperidone and other antipsychotics with small effect sizes (see Fig. 2D) [90]. Evidence does not support superiority of clozapine for hospitalization rate vs. SGAs (see Supplementary Fig. 16) or reduction of suicide/self-injurious behavior vs. SGAs in observational studies [82] (see Supplementary Fig. 17), and does not support superiority for anti-suicidal effects in long-term RCTs vs. olanzapine [29], but meta-analytic evidence from one long-term trial (n = 980) showed superior effects of clozapine vs. olanzapine [67] (see Supplementary Fig. 17). Meta-analytic evidence suggests superior effects of clozapine on hostility compared to FGAs in RCTs in mixed short-, medium-, and long-term RCTs with a medium effect size [50] (see Fig. 2F) and on cognition vs. SGAs in TRS in observational studies with a small effect size [82] (see Fig. 2F), whereas mostly nonsignificant effects on cognition compared to FGAs and SGAs [119] were observed in RCTs and even inferior effects vs. single FGAs, e.g. sertindole [89] (see Fig. 2F). With regard to psychosocial functioning, clozapine appears not to have significantly more beneficial effects compared to SGAs [92] (see Fig. 2E). For quality of life, available data is scarce (see Fig. 2E). A detailed report with regard to different disease entities and levels is presented in the Supplementary Results S1 (https://github.com/sksiafis/clozapine_meta_review). For additional outcomes, please see Supplementary Figs. S1–S19.

Other efficacy measures in BP and PDP

No superior efficacy of clozapine vs. other antipsychotics could be shown for mania in bipolar disorder short-term [45] (see Fig. 2F). For PDP, clozapine seems to be superior vs. quetiapine short-term in terms of clinical global impression with large effect sizes [51] (see Fig. 2D). A detailed report with regard to different disease entities and levels is presented in the Supplementary Results S1 (https://github.com/sksiafis/clozapine_meta_review).

Tolerability of clozapine (SMD and RR)

Clozapine is equivocally associated with a significantly higher risk for weight gain with small to medium effect sizes (see Fig. 3A) and an increased risk to develop type 2 diabetes compared to most other antipsychotics [93] and with significantly fewer EPS or use of antiparkinson medication compared to FGAs with small effect sizes [48, 81, 125], SGAs [121] with large effect size and especially risperidone with a medium effect size [29, 96] (see Fig. 3E and F). Despite an unfavorable profile regarding sedation/dizziness, anticholinergic, hematological, and cardiac events, different metabolic outcomes and dropouts due to adverse events compared to both FGAs and SGAs with small to large effect sizes (see Fig. 2B, C, G, H, J, K) clozapine is associated with a significantly lower mortality [124]. A detailed report with regard to different diseases entities and levels is presented in the Supplementary Results S1 (https://github.com/sksiafis/clozapine_meta_review). For additional outcomes, please see Supplementary Figs. S1–S19.

A Weight as continuous outcome. BMI body-mass-index, k number of studies, kg kilogram, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized-controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. For continuous outcomes, SMD > 0 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events. B Lipid levels. k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized-controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. C Glucose, insulin and inulin resistance levels. FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized-controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. For continuous outcomes, SMD > 0 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events. D Weight as dichotomous outcome. FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized-controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. For dichotomous outcomes, RR > 1 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events/dropouts). E Extrapyramidal symptoms as measured by scales. k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized-controlled trial, S short-term, SAS Simpson–Angus Scale, SGA second-generation antipsychotic, TD tardive dyskinesia. For continuous outcomes, SMD > 0 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events. F Extrapyramidal symptoms as dichotomous outcome. EPS extrapyramidal symptoms, FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized-controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. For dichotomous outcomes, RR > 1 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events/dropouts). G (Anti-)cholinergic symptoms. FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized-controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. For dichotomous outcomes, RR > 1 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events/dropouts). H Sedation and dizziness. FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized-controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. For dichotomous outcomes, RR > 1 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events/dropouts). I Other CNS symptoms (insomnia, headache, seizures, anxiety). FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized-controlled trial, S short-term, SGA second-generation antipsychotic. For dichotomous outcomes, RR > 1 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events/dropouts). J WBC abnormalities. FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized-controlled trial, S short-term, WBC white blood count. For dichotomous outcomes, RR > 1 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events/dropouts). K Any adverse event and dropouts due to adverse events. FGA first-generation antipsychotic, k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized-controlled trial, S short-term. For dichotomous outcomes, RR > 1 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events/dropouts).

Efficacy of pharmacological add-on strategies to improve clozapine-related adverse-events

Metformin and GLP1-RA as add-on strategies seem promising for improving metabolic outcomes short-term with mostly small effect sizes [108, 131], but also aripiprazole appears effective in terms of short-term weight reduction and reduction of lipid levels with small effect sizes [112]. Limited evidence is available for the efficacy of topiramate for weight reduction [43]. Evidence is scarce for clozapine-related hypersalivation and constipation treatment [41, 49, 115] (see Fig. 4A, B). A detailed report with regard to different disease entities and levels is presented in the Supplementary Results S1 (https://github.com/sksiafis/clozapine_meta_review) and in the Supplementary Figs. S18, 19.

A Treatment options for clozapine-associated metabolic dysfunctions. BMI body-mass index, cm centimeter, GLP-1RA GLP-1 receptor agonist, HDL high-density lipoprotein, HOMA homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance, k number of studies, kg kilogram, L long-term, LDL low-density lipoprotein, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized-controlled trial, S short-term. For continuous outcomes, SMD > 0 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events. B Treatment options for clozapine-associated hypersalivation. k number of studies, L long-term, M medium-term, n number of participants, RCT randomized-controlled trial, S short-term. For dichotomous outcomes, RR > 1 means a beneficial outcome for clozapine (e.g. more response or less adverse events/dropouts).

Discussion

In our meta-review, we aimed at synthesizing all available evidence for clozapine’s efficacy and safety across all medical conditions where clozapine is used. We were able to give a systematic overview of all relevant clozapine indications and clozapine-associated endpoints derived from a total of 112 meta-analyses. Based on this overview and the methodological evaluation of all included meta-analyses, guideline developers and clinicians are now able to provide a strict risk-benefit evaluation taking into consideration all dimensions of clozapine treatment.

Symptomatic endpoints

Clozapine is significantly superior to placebo and superior to FGAs with regard to overall and positive symptoms according to high-quality meta-analytic evidence from RCTs [48, 76]. Meta-analytic evidence suggests significant superiority of clozapine in terms of efficacy on overall and positive symptoms compared to most SGAs [29, 85, 121, 122, 125] even though results are inconsistent [79].

With regard to evidence for clozapine’s effectiveness derived from observational studies, clozapine is associated with significantly lower hospitalization and ACD rate compared with other SGAs [65, 82]. For multi-episode schizophrenia and TRS, the superiority of clozapine compared to other SGAs is challenged according to meta-analytic evidence derived from RCTs: specifically for multi-episode schizophrenia (excluding TRS), clozapine appears to be not significantly different from e.g. amisulpride, olanzapine, zotepine and risperidone in terms of overall symptoms [57]. For TRS, clozapine is presumed to be not more efficacious than olanzapine, risperidone or ziprasidone in the subanalyses including only TRS trials in overall symptoms in the meta-analysis from Leucht et al. [79] being in line with the evidence from the meta-analysis from Samara et al. [100], where also only blinded RCTs were included and clozapine was not significantly superior to most other APs with regard to overall symptom reduction [100].

For treatment-resistant positive symptoms, clozapine seems to have significantly superior beneficial effects compared to quetiapine and haloperidol on single-substance level, but not compared to olanzapine [100]. When comparators are pooled as a group (FGA + SGA) clozapine was shown to have superior effects for treatment-resistant overall and positive symptoms [85, 106]. Nevertheless, for overall and positive symptoms in TRS, inconsistent evidence is reported in meta-analyses due to differences in study selections, study populations, in the handling of study characteristics, and in methodological approaches [100, 106].

For treatment-resistant negative symptoms, clozapine was shown to be slightly superior to FGAs [48] despite inconsistent results [73], but—according to a large body of evidence—not significantly superior in comparison to SGAs [29, 85, 121], and if, then only on short-term [106]. Nevertheless, negative symptom data did not include a separation of primary from secondary negative symptoms, which hampers interpretability of the results.

For cognition and psychosocial functioning, clozapine is not presumed to be significantly superior compared to other SGAs [89, 92]. While evidence for the efficacy of clozapine for first-episode psychosis is scarce [128], limited evidence suggests superior effects for clozapine as a second-line agent compared to other antipsychotics, such as, e.g. risperidone [90].

Clozapine shows beneficial effects on psychosocial function but without superiority to other antipsychotics [92]. Inconclusive results are available for pro-cognitive effects of clozapine vs. FGAs and SGAs [89, 119, 126]. For children with schizophrenia and childhood-onset schizophrenia, clozapine seems to have superior efficacy compared with FGAs [60, 74]. Limited evidence is available for schizophrenia and comorbid depression or comorbid substance abuse, but when clozapine was compared with any other antipsychotic drug plus an antidepressant or placebo, patients treated with clozapine constantly scored better on Hamilton scores [52], and clozapine was superior to other antipsychotics in substance use [71] and to risperidone in reducing craving for cannabis [118]. Furthermore, clozapine is likely to have some beneficial effects on hostility [50], suicidal behavior [56]—and maybe aggression versus others in schizophrenia, at least when compared with FGAs [62]. Nevertheless, negative evidence for suicidal behavior and self-injurious behavior for clozapine vs. SGA in observational studies was also reported [82]. Of note, meta-analytic evidence for the efficacy of clozapine in suicidal symptoms is mainly from registry data and non-randomized trials, whereas to our knowledge, only one high-quality RCT [132] fosters the evidence and contributes to long-term RCT data [29]. With regard to dosing, there is only little meta-analytic evidence that in studies with mean clozapine dosages above 400 mg/day, clozapine was superior to risperidone, but not olanzapine [79] and evidence of effects between clozapine standard, low and very low dose regimes on overall outcome in schizophrenia is sparse [114]. For bipolar disorder, the efficacy of clozapine seems to be similar to other antipsychotics in manic episodes [45]. For neurological disorders, the largest body of evidence is available for PDP, where low-dose clozapine (range from 12.5 to 50 mg) showed beneficial effects on psychotic symptoms) [51, 58] even though negative results are reported [127].

Non-symptomatic efficacy/effectiveness endpoints

Limited evidence hints at superior effects vs. SGAs in reducing drug abuse in schizophrenia short and medium-term [71, 118]. With regard to relapse prevention, clozapine is superior to FGAs [48, 77] and SGAs [125], even though results in the latter are inconsistent [64]. Mortality rate ratios seem to be lower in patients continuously treated with clozapine compared to patients on non-clozapine antipsychotics [82, 124]. Clozapine significantly reduces hospitalization rates compared to non-clozapine SGAs [75, 82] and all-cause discontinuation rates [65, 82].

Clozapine-related adverse-events and complications

There is a strong body of meta-analytic evidence for especially unfavorable metabolic outcomes (e.g. weight gain) [78, 93], also for first-episode schizophrenia patients [128]. In line with meta-analytic evidence for weight gain and the increased risk for the onset of metabolic syndrome, treatment guidelines for adult patients with schizophrenia have previously suggested not to use clozapine as a first-line agent [3]. The application among elderly patients with schizophrenia remains to be further investigated [17]. Meta-analytic evidence unequivocally suggests that clozapine is associated with a lower risk for EPS and/or tardive dyskinesia compared to other FGAs and SGAs [38, 81]. Of note, meta-analytic evidence suggests clozapine as favorable therapeutic antipsychotic agent for the event of TD [83]. Clozapine use significantly increases the risk for gastrointestinal hypomotility/constipation compared to other APs [104], but no meta-analytic data is available for the prevalence of clozapine-related (sub-) ileus.

Clozapine appears to be the most unfavorable antipsychotic for sedation compared to FGAs and other SGAs [29, 78]. With regard to pneumonia, the only available meta-analytic evidence suggests that clozapine significantly increases pneumonia risk compared to no antipsychotic use [47], but in general, evidence suggests that clozapine-related pneumonia [47, 133] might be overseen.

The incidence for clozapine-associated neutropenia is presumed to be 3.8% and severe neutropenia (agranulocytosis) between 0.4% [18] and 0.9% [88], respectively according to two meta-analyses of observational studies and—according to another meta-analysis—the relative risk for neutropenia is not significantly associated with any individual clozapine add-on antipsychotic medication [87]. Death caused by clozapine-related agranulocytosis appears to be at 0.05% [18]. Meta-analytic evidence suggests a low event rate of both clozapine-related myocarditis (0.7%) and cardiomyopathia (0.6%) [16]. Nevertheless, clozapine’s potential effect to cause arrhythmia [28] might be overseen, as reflected in a low amount of evidence. For PDP, low-dose clozapine appears to be relatively safe compared to placebo with mixed results for the effects on motor symptoms [51, 58].

Treatment of clozapine-related adverse events and complications

Metformin [108], GLP-1RAs [105] and to a lesser extent aripiprazole [112] seem to be beneficial add-on-agents for the management of clozapine-related weight gain. Metformin was superior to placebo in terms of weight loss and BMI [108]. GLP-1RAs led to a significantly higher weight loss compared to control (placebo or usual care) [105] and aripiprazole was superior with regard to weight change and LDL-cholesterol compared to placebo [112]. In all scenarios, a close risk-benefit evaluation has to be performed, since e.g. the add-on use of aripiprazole was significantly associated with agitation/akathisia and anxiety [112].

For the treatment of clozapine-related constipation, there is not enough evidence from clinical trials to inform clinical practice [49], as it is the case for clozapine-related sinustachycardia, where no data for specific clinical interventions, e.g. the use of beta-blockers is available from clinical trials [26].

The results of this meta-review should be interpreted with caution due to the inherent limitations of the meta-analyses and their included studies. The quality of meta-analyses was evaluated using the AMSTAR-2 tool, which includes items for heterogeneity and publication bias, yet further exploration of their impact on meta-analytic estimates is out of the scope of this manuscript. In addition, overlapping meta-analyses on the same topic may have different results due to different eligibility criteria and statistical methods [134], such as differences about the efficacy of clozapine for treatment-resistance schizophrenia [100, 106]. Limitations of the included studies could also impact meta-analytic estimates, i.e. a meta-analysis of observational studies investigating mortality during treatment with clozapine [135]. The potential impact of study-level (e.g. rating scale used to measure symptom improvement), and participant-level factors (such as race/ethnicity) or other confounding factors specifically in observational studies (such as concomitant medications) could not be easily addressed at the level of an umbrella review. Our meta-review represents the first comprehensive quantitative analysis of clozapine with regard to its efficacy and safety in schizophrenia, schizoaffective and bipolar disorder and PDP. Our meta-review outlines the superior efficacy of clozapine compared to FGAs and most other SGAs in schizophrenia and suggests beneficial outcomes in bipolar disorder and PDP. Nevertheless, evidence to manage clozapine-related adverse-events is sparse. In addition, more studies are needed regarding the safety of clozapine beyond the scope of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Our quantitative meta-review suggests that if routine hematological monitoring and screening for the early detection of myocarditis are performed, a close and continuous risk-benefit evaluation with regard to cardiovascular risk factors is key to improve clozapine-related outcomes.

References

Idanpaan-Heikkila J, Alhava E, Olkinuora M, Palva IP. Agranulocytosis during treatment with chlozapine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1977;11:193–198.

Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen psychiatry. 1988;45:789–96.

Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, Noel JM, Boggs DL, Fischer BA, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophrenia Bull. 2010;36:71–93.

Barnes TR. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:567–620.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental H. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management: updated edition 2014. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) Copyright (c) National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health; 2014.

Nielsen J, Young C, Ifteni P, Kishimoto T, Xiang YT, Schulte PF, et al. Worldwide differences in regulations of clozapine use. CNS Drugs. 2016;30:149–61.

Howes OD, McCutcheon R, Agid O, de Bartolomeis A, van Beveren NJ, Birnbaum ML, et al. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: Treatment Response and Resistance in Psychosis (TRRIP) Working Group consensus guidelines on diagnosis and terminology. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:216–29.

Eaton WW, Pedersen MG, Nielsen PR, Mortensen PB. Autoimmune diseases, bipolar disorder, and non-affective psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:638–46.

Goodwin GM. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised second edition–recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23:346–88.

Üçok A, Çikrikçili U, Karabulut S, Salaj A, Öztürk M, Tabak Ö, et al. Delayed initiation of clozapine may be related to poor response in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30:290–295.

World Health Organisation. WHO Model list of Essential Medicines, 20th List. 2017.

Shah P, Iwata Y, Plitman E, Brown EE, Caravaggio F, Kim J, et al. The impact of delay in clozapine initiation on treatment outcomes in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2018;268:114–22.

Thien K, O’Donoghue B. Delays and barriers to the commencement of clozapine in eligible people with a psychotic disorder: a literature review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13:18–23.

Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000326.

Wagner E, Löhrs L, Siskind D, Honer WG, Falkai P, Hasan A. Clozapine augmentation strategies—a systematic meta-review of available evidence. Treatment options for clozapine resistance. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33:423–35.

Siskind D, Sidhu A, Cross J, Chua YT, Myles N, Cohen D, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of rates of clozapine-associated myocarditis and cardiomyopathy. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2020;54:4867419898760–481.

Krause M, Huhn M, Schneider-Thoma J, Rothe P, Smith RC, Leucht S. Antipsychotic drugs for elderly patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28:1360–70.

Li XH, Zhong XM, Lu L, Zheng W, Wang SB, Rao WW, et al. The prevalence of agranulocytosis and related death in clozapine-treated patients: a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies. Psychol. Med. 2020;50:583–94.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–12.

R Core Team. R :2019: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Vol. 3. 2020. Available online at https://www.R-project.org/.

Wickham et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019;4:1686.

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd Edition. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons, 2019.

Borenstein MCH, Hedges L, Valentine J. Effect sizes for continuous data. In: The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. H. Cooper, L. V. Hedges, & J. C. Valentine (Eds.). Russell Sage Foundation. 2009. p. 221–235.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2017;358:j4008.

Higgins. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. 2011.

Lally J, Docherty MJ, MacCabe JH. Pharmacological interventions for clozapine-induced sinus tachycardia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;6:Cd011566.

Ayub M, Saeed K, Munshi TA, Naeem F. Clozapine for psychotic disorders in adults with intellectual disabilities. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:Cd010625.

Alvares GA, Quintana DS, Hickie IB, Guastella AJ. Autonomic nervous system dysfunction in psychiatric disorders and the impact of psychotropic medications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2016;41:89–104.

Asenjo Lobos C, Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, Hunger H, Schmid F, Schwarz S, et al. Clozapine versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Online). 2010;11:CD006633.

Asmal L, Flegar SJ, Wang J, Rummel-Kluge C, Komossa K, Leucht S. Quetiapine versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:Cd006625.

Bai Z, Wang G, Cai S, Ding X, Liu W, Huang D, et al. Efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of 8 atypical antipsychotics in Chinese patients with acute schizophrenia: a network meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Res. 2017;185:73–79.

Bak M, Fransen A, Janssen J, Van Os J, Drukker M. Almost all antipsychotics result in weight gain: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e94112 (no pagination).

Bartoli F, Crocamo C, Clerici M, Carra G. Second-generation antipsychotics and adiponectin levels in schizophrenia: a comparative meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25:1767–74.

Bartoli F, Lax A, Crocamo C, Clerici M, Carra G. Plasma adiponectin levels in schizophrenia and role of second-generation antipsychotics: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;56:179–89.

Beasley CM Jr, Stauffer VL, Liu-Seifert H, Taylor CC, Dunayevich E, Davis JM, Jr. All-cause treatment discontinuation in schizophrenia during treatment with olanzapine relative to other antipsychotics: an integrated analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2007;27:252–8.

Bergman H, Rathbone J, Agarwal V, Soares-Weiser K. Antipsychotic reduction and/or cessation and antipsychotics as specific treatments for tardive dyskinesia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018; 2018 (no pagination) (CD000459).

Buhagiar K, Jabbar F. Association of first- vs. second-generation antipsychotics with lipid abnormalities in individuals with severe mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Drug Investig. 2019;39:253–273.

Carbon M, Kane JM, Leucht S, Correll CU. Tardive dyskinesia risk with first- and second-generation antipsychotics in comparative randomized controlled trials: a meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2018;17:330–340.

Chakos M, Lieberman J, Hoffman E, Bradford D, Sheitman B. Effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:518–526.

Cheine MV, Wahlbeck K, Rimon M. Pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia resistant to first-line treatment: a critical systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 1999;3:159–169.

Chen SY, Ravindran G, Zhang Q, Kisely S, Siskind D. Treatment strategies for clozapine-induced sialorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2019;33:225–238.

Cohen D, Bonnot O, Bodeau N, Consoli A, Laurent C. Adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a bayesian meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32:309–316.

Correll CU, Maayan L, Kane J, De Hert M, Cohen D. Efficacy for psychopathology and body weight and safety of topiramate-antipsychotic cotreatment in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: results from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:e746–e756.

Davis JM, Chen N, Glick ID. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:553–564.

Delgado A, Velosa J, Zhang J, Dursun SM, Kapczinski F, de Azevedo Cardoso T. Clozapine in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;125:21–27.

Duggan L, Fenton M, Rathbone J, Dardennes R, El-Dosoky A, Indran S. Olanzapine for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Online). 2005;2:CD001359.

Dzahini O, Singh N, Taylor D, Haddad PM. Antipsychotic drug use and pneumonia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32:1167–1181.

Essali A, Al-Haj Haasan N, Li C, Rathbone J. Clozapine versus typical neuroleptic medication for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; (no pagination)(CD000059).

Every-Palmer S, Newton-Howes G, Clarke MJ. Pharmacological treatment for antipsychotic-related constipation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1:Cd011128.

Faay MDM, Czobor P, Sommer IEC. Efficacy of typical and atypical antipsychotic medication on hostility in patients with psychosis-spectrum disorders: a review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:2340–2349.

Frieling H, Hillemacher T, Ziegenbein M, Neundorfer B, Bleich S. Treating dopamimetic psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: structured review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17:165–171.

Furtado VA, Srihari V. Atypical antipsychotics for people with both schizophrenia and depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:Cd005377.

Geddes J, Freemantle N, Harrison P, Bebbington P. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: systematic overview and meta-regression analysis. Br Med J. 2000;321:1371–1376.

Glick ID, Correll CU, Altamura AC, Marder SR, Csernansky JG, Weiden PJ, et al. Mid-term and long-term efficacy and effectiveness of antipsychotic medications for schizophrenia: a data-driven, personalized clinical approach. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:1616–1627.

Hartling L, Abou-Setta AM, Dursun S, Mousavi SS, Pasichnyk D, Newton AS. Antipsychotics in adults with schizophrenia: comparative effectiveness of first-generation versus second-generation medications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:498–511.

Hennen J, Baldessarini RJ. Suicidal risk during treatment with clozapine: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2005;73:139–145.

Huhn M, Nikolakopoulou A, Schneider-Thoma J, Krause M, Samara M, Peter N, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394:939–951.

Iketani R, Kawasaki Y, Yamada H. Comparative utility of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2017;40:1976–1982.

Jethwa KD, Onalaja OA. Antipsychotics for the management of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych open. 2015;1:27–33.

Kennedy E, Kumar A, Datta SS. Antipsychotic medication for childhood-onset schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2007 (no pagination)(CD004027).

Khanna P, Suo T, Komossa K, Ma H, Rummel-Kluge C, El-Sayeh HG, et al. Aripiprazole versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:Cd006569.

Khushu A, Powney MJ. Haloperidol for long-term aggression in psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:Cd009830.

Kishi T, Ikuta T, Matsunaga S, Matsuda Y, Oya K, Iwata N. Comparative efficacy and safety of antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a network meta-analysis in a Japanese population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1281–1302.

Kishimoto T, Agarwal V, Kishi T, Leucht S, Kane JM, Correll CU. Relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of second-generation antipsychotics versus first-generation antipsychotics. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:53–66.

Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Nitta M, Kane JM, Correll CU. Long-term effectiveness of oral second-generation antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of direct head-to-head comparisons. World Psychiatry. 2019;18:208–224.

Klemp M, Tvete IF, Skomedal T, Gaasemyr J, Natvig B, Aursnes I. A review and bayesian meta-analysis of clinical efficacy and adverse effects of 4 atypical neuroleptic drugs compared with haloperidol and placebo. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31:698–704.

Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, Schmid F, Hunger H, Schwarz S, Srisurapanont M, et al. Quetiapine versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:Cd006625.

Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, Hunger H, Schmid F, Schwarz S, Kissling W, et al. Zotepine versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Online). 2010;1:CD006628.

Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, Hunger H, Schwarz S, Bhoopathi PS, Kissling W, et al. Ziprasidone versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:Cd006627.

Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, Schwarz S, Schmid F, Hunger H, Kissling W, et al. Risperidone versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Online). 2011;1:CD006626.

Krause M, Huhn M, Schneider-Thoma J, Bighelli I, Gutsmiedl K, Leucht S. Efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia and comorbid substance use. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29:32–45.

Krause M, Zhu Y, Huhn M, Schneider-Thoma J, Bighelli I, Chaimani A, et al. Efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of antipsychotics in children and adolescents with schizophrenia: a network meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28:659–674.

Krause M, Zhu Y, Huhn M, Schneider-Thoma J, Bighelli I, Nikolakopoulou A, et al. Antipsychotic drugs for patients with schizophrenia and predominant or prominent negative symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;268:625–639.

Kumar A, Datta SS, Wright SD, Furtado VA, Russell PS. Atypical antipsychotics for psychosis in adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:Cd009582.

Land R, Siskind D, McArdle P, Kisely S, Winckel K, Hollingworth SA. The impact of clozapine on hospital use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135:296–309.

Leucht S, Arbter D, Engel RR, Kissling W, Davis JM. How effective are second-generation antipsychotic drugs? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:429–447.

Leucht S, Barnes TR, Kissling W, Engel RR, Correll C, Kane JM. Relapse prevention in schizophrenia with new-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1209–1222.

Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382:951–962.

Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, Engel RR, Li C, Davis JM. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:31–41.

Leucht S, Samara M, Heres S, Patel MX, Woods SW, Davis JM. Dose equivalents for second-generation antipsychotics: the minimum effective dose method. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:314–326.

Leucht S, Wahlbeck K, Hamann J, Kissling W. New generation antipsychotics versus low-potency conventional antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361:1581–1589.

Masuda T, Misawa F, Takase M, Kane JM, Correll CU. Association with hospitalization and all-cause discontinuation among patients with schizophrenia on clozapine vs other oral second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:1052–1062.

Mentzel TQ, et al. Clozapine monotherapy as a treatment for antipsychotic-induced tardive dyskinesia: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2018;79:17r11852.

Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, Sweers K, van Winkel R, Yu W, De Hert M. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:306–318.

Mizuno Y, McCutcheon RA, Brugger SP, Howes OD. Heterogeneity and efficacy of antipsychotic treatment for schizophrenia with or without treatment resistance: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020;45:622–631.

Moncrieff J. Clozapine v. conventional antipsychotic drugs for treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a re-examination. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:161–166.

Myles N, Myles H, Xia S, Large M, Bird R, Galletly C, et al. A meta-analysis of controlled studies comparing the association between clozapine and other antipsychotic medications and the development of neutropenia. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2019;53:403–412.

Myles N, Myles H, Xia S, Large M, Kisely S, Galletly C, et al. Meta-analysis examining the epidemiology of clozapine-associated neutropenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138:101–109.

Nielsen RE, Levander S, Kjaersdam Telléus G, Jensen SO, Østergaard Christensen T, Leucht S. Second-generation antipsychotic effect on cognition in patients with schizophrenia–a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;131:185–196.

Okhuijsen-Pfeifer C, Huijsman E, Hasan A, Sommer I, Leucht S, Kahn RS, et al. Clozapine as a first- or second-line treatment in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138:281–288.

Okhuijsen-Pfeifer C, Sterk AY, Horn IM, Terstappen J, Kahn RS, Luykx JJ. Demographic and clinical features as predictors of clozapine response in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;111:246–252.

Olagunju AT, Clark SR, Baune BT. Clozapine and psychosocial function in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2018;32:1011–1023.

Pillinger T, McCutcheon RA, Vano L, Mizuno Y, Arumuham A, Hindley G, et al. Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:64–77.

Potvin S, Zhornitsky S, Stip E. Antipsychotic-induced changes in blood levels of leptin in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Can J Psychiatry 2015; Rev Canad Psychiatr. 60:S26–S34.

Pringsheim T, Lam D, Ching H, Patten S. Metabolic and neurological complications of second-generation antipsychotic use in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug Saf. 2011;34:651–668.

Rummel-Kluge C, Komossa K, Schwarz S, Hunger H, Schmid F, Kissling W, et al. Second-generation antipsychotic drugs and extrapyramidal side effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:167–177.

Rummel-Kluge C, Komossa K, Schwarz S, Hunger H, Schmid F, Lobos CA, et al. Head-to-head comparisons of metabolic side effects of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;123:225–233.

Salvo F, Pariente A, Shakir S, Robinson P, Arnaud M, Thomas S, et al. Sudden cardiac and sudden unexpected death related to antipsychotics: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99:306–314.

Samara MT, Cao H, Helfer B, Davis JM, Leucht S. Chlorpromazine versus every other antipsychotic for schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis challenging the dogma of equal efficacy of antipsychotic drugs. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24:1046–1055.

Samara MT, Dold M, Gianatsi M, Nikolakopoulou A, Helfer B, Salanti G, et al. Efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of antipsychotics in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:199–210.

Sarkar S, Grover S. Antipsychotics in children and adolescents with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Pharmacol. 2013;45:439–446.

Serretti A, Chiesa A. A meta-analysis of sexual dysfunction in psychiatric patients taking antipsychotics. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;26:130–140.

Sherwood M, Thornton AE, Honer WG. A quantitative review of the profile and time course of symptom change in schizophrenia treated with clozapine. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:1175–1184.

Shirazi A et al. Prevalence and predictors of Clozapine-associated constipation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci 2016; 17 (no pagination)(863).

Siskind D, Hahn M, Correll CU, Fink-Jensen A, Russell AW, Bak N, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists for antipsychotic-associated cardio-metabolic risk factors: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:293–302.

Siskind D, McCartney L, Goldschlager R, Kisely S. Clozapine v. first- and second-generation antipsychotics in treatment-refractory schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;205:385–392.

Siskind D, Siskind V, Kisely S. Clozapine response rates among people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: data from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62:772–777.

Siskind DJ, Leung J, Russell AW, Wysoczanski D, Kisely S. Metformin for clozapine associated obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2016; 11 (no pagination)(e0156208).

Smith M, Hopkins D, Peveler RC, Holt RI, Woodward M, Ismail K. First- v. second-generation antipsychotics and risk for diabetes in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:406–411.

Soares-Weiser K, Bechard-Evans L, Lawson AH, Davis J, Ascher-Svanum H. Time to all-cause treatment discontinuation of olanzapine compared to other antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:118–125.

Souza JS, Kayo M, Tassell I, Martins CB, Elkis H. Efficacy of olanzapine in comparison with clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analyses. CNS Spectr. 2013;18:82–89.

Srisurapanont M, Suttajit S, Maneeton N, Maneeton B. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole augmentation of clozapine in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;62:38–47.

Subramanian S, Rummel-Kluge C, Hunger H, Schmid F, Schwarz S, Kissling W, et al. Zotepine versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;10:CD006628.

Subramanian S, Vollm BA, Huband N. Clozapine dose for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:Cd009555.

Syed R, Au K, Cahill C, Duggan L, He Y, Udu V, et al. Pharmacological interventions for clozapine-induced hypersalivation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:Cd005579.

Szegedi A, Verweij P, van Duijnhoven W, Mackle M, Cazorla P, Fennema H. Meta-analyses of the efficacy of asenapine for acute schizophrenia: comparisons with placebo and other antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1533–1540.

Tek C, Kucukgoncu S, Guloksuz S, Woods SW, Srihari VH, Annamalai A. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain in first-episode psychosis patients: a meta-analysis of differential effects of antipsychotic medications. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10:193–202.

Temmingh HS, Williams T, Siegfried N, Stein DJ. Risperidone versus other antipsychotics for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance misuse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1:Cd011057.

Thornton AE, Van Snellenberg JX, Sepehry AA, Honer WG. The impact of atypical antipsychotic medications on long-term memory dysfunction in schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a quantitative review. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:335–346.

Tsuda Y, Saruwatari J, Yasui-Furukori N. Meta-analysis: The effects of smoking on the disposition of two commonly used antipsychotic agents, olanzapine and clozapine. BMJ Open 2014;4 (no pagination)(e004216).

Tuunainen A, Wahlbeck K, Gilbody S. Newer atypical antipsychotic medication in comparison to clozapine: a systematic review of randomized trials. Schizophr Res. 2002;56:1–10.

Tuunainen A, Wahlbeck K, Gilbody SM. Newer atypical antipsychotic medication versus clozapine for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:Cd000966.

Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Mitchell AJ, De Hert M, Wampers M, Ward PB, et al. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2015;14:339–347.

Vermeulen JM, van Rooijen G, van de Kerkhof M, Sutterland AL, Correll CU, de Haan L. Clozapine and long-term mortality risk in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies lasting 1.1–12.5 years. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45:315–329.

Wahlbeck K, Cheine M, Essali A, Adams C. Evidence of clozapine’s effectiveness in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:990–999.

Woodward ND, Purdon SE, Meltzer HY, Zald DH. A meta-analysis of neuropsychological change to clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8:457–472.

Zhang H, Wang L, Fan Y, Yang L, Wen X, Liu Y, et al. Atypical antipsychotics for Parkinson’s disease psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:2137–2149.

Zhang JP, Gallego JA, Robinson DG, Malhotra AK, Kane JM, Correll CU. Efficacy and safety of individual second-generation vs. first-generation antipsychotics in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:1205–1218.

Zhang Y, et al. The metabolic side effects of 12 antipsychotic drugs used for the treatment of schizophrenia on glucose: a network meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2017; 17 (no pagination)(373).

Zheng W, Xiang YT, Xiang YQ, Li XB, Ungvari GS, Chiu HF, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive topiramate for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134:385–398.

Zimbron J, Khandaker GM, Toschi C, Jones PB, Fernandez-Egea E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of treatments for clozapine-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26:1353–1365.

Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, Altamura AC, Anand R, Bertoldi A, et al. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT). Arch Gen psychiatry. 2003;60:82–91.

de Leon J, Sanz EJ, Noren GN, De Las Cuevas C. Pneumonia may be more frequent and have more fatal outcomes with clozapine than with other second-generation antipsychotics. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:120–121.

Palpacuer C, Hammas K, Duprez R, Laviolle B, Ioannidis J, Naudet F. Vibration of effects from diverse inclusion/exclusion criteria and analytical choices: 9216 different ways to perform an indirect comparison meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2019;17:174.

van der Zalm YC, Termorshuizen F, Selten JP. Concerns about bias in studies on clozapine and mortality. Schizophr Res. 2019;204:425–426.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors contributed either substantially to the conception or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work. EW, SS, and AH are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

EW, SS, PF, DS, and AR reports no competing interests. WGH has received consulting fees or sat on paid advisory boards for: AlphaSights, Guidepoint, In Silico, Translational Life Sciences, Otsuka, AbbVie and Newron, and holds/held shares in Translational Life Sciences, AbCellera and Eli Lilly. PF was honorary speaker for Janssen-Cilag, Astra-Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Bristol Myers-Squibb, Lundbeck, Pfizer, Bayer Vital, SmithKline Beecham, Wyeth, and Essex. During the last 5 years he was a member of the advisory boards of Janssen-Cilag, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, and Lundbeck. Presently, he is a member of the advisory boards of Richter Pharma, Böhringer-Ingelheim and Otsuka. SL has received honoraria as a consultant/advisor and/or for lectures from Angelini, Böhringer Ingelheim, Geodon & Richter, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, LTS Lohmann, MSD, Otsuka, Recordati, SanofiAventis, Sandoz, Sunovion, TEVA. AH has been invited to scientific meetings by Lundbeck, Janssen-Cilag, and Pfizer, and he received paid speakerships from Desitin, Janssen-Cilag, Otsuka and Lundbeck. He was member of Roche, Otsuka, Lundbeck and Janssen-Cilag advisory boards.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wagner, E., Siafis, S., Fernando, P. et al. Efficacy and safety of clozapine in psychotic disorders—a systematic quantitative meta-review. Transl Psychiatry 11, 487 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01613-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01613-2

This article is cited by

-

Management von Therapieresistenzen – therapieresistente Schizophrenie

Der Nervenarzt (2024)

-

Polygenic liability for antipsychotic dosage and polypharmacy - a real-world registry and biobank study

Neuropsychopharmacology (2024)

-

Chancen durch Off-Label-Therapie

InFo Neurologie + Psychiatrie (2023)

-

A Guideline and Checklist for Initiating and Managing Clozapine Treatment in Patients with Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia

CNS Drugs (2022)