Abstract

Improving the coherence of superconducting qubits is a fundamental step towards the realization of fault-tolerant quantum computation. However, coherence times of quantum circuits made from conventional aluminum-based Josephson junctions are limited by the presence of microscopic two-level systems in the amorphous aluminum oxide tunnel barriers. Here, we have developed superconducting qubits based on NbN/AlN/NbN epitaxial Josephson junctions on silicon substrates which promise to overcome the drawbacks of qubits based on Al/AlOx/Al junctions. The all-nitride qubits have great advantages such as chemical stability against oxidation, resulting in fewer two-level fluctuators, feasibility for epitaxial tunnel barriers that reduce energy relaxation and dephasing, and a larger superconducting gap of ~5.2 meV for NbN, compared to ~0.3 meV for aluminum, which suppresses the excitation of quasiparticles. By replacing conventional MgO by a silicon substrate with a TiN buffer layer for epitaxial growth of nitride junctions, we demonstrate a qubit energy relaxation time \({T}_{1}=16.3\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) and a spin-echo dephasing time \({T}_{2}=21.5\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\). These significant improvements in quantum coherence are explained by the reduced dielectric loss compared to the previously reported \({T}_{1}\approx {T}_{2}\approx 0.5\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) of NbN-based qubits on MgO substrates. These results are an important step towards constructing a new platform for superconducting quantum hardware.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the first demonstration of nanosecond-scale quantum coherence in a charge qubit in 19991, superconducting qubits have developed into a leading platform for scalable quantum computing, as evidenced by recent key demonstrations including quantum algorithms2,3, quantum error correction4,5,6, and quantum supremacy7. However, their gate fidelities still need to be improved further for building a fault-tolerant quantum computer, even though two-qubit gates with fidelities as high as 99.7%8 have recently been achieved (cf. the case of trapped-ion qubits above 99.9%9).

The remarkable progress of superconducting qubits has to a large extent resulted from the innovative five-order increase in their coherence times by improving circuit designs, materials, and fabrication processes10,11,12. Looking at material-based improvements, most of the research has been focused on materials for capacitors or microwave resonators (e.g., niobium titanium nitride (NbTiN)13, TiN14, and tantalum (Ta)15 instead of the commonly used niobium (Nb) or aluminum (Al)) in order to reduce microwave dielectric loss induced by uncontrolled defects in oxides at their surfaces and interfaces. In contrast, alternative materials for the Josephson junctions (JJs) of the qubits have not been studied adequately, even though it has been pointed out that the coherence times of superconducting quantum circuits made from conventional Al-based JJs are limited by energy or phase relaxation due to microscopic two-level systems (TLSs) in the amorphous aluminum oxide (AlOx) tunnel barriers16,17,18. Therefore, a breakthrough in the further improvement of superconducting qubits can be expected by exploring alternative materials for JJs.

One promising approach to reduce the number of TLSs in a JJ is to use a crystalline tunnel barrier as demonstrated with epitaxial Al2O3 layers grown on crystalline Re films19,20. From this viewpoint, fully epitaxial nitride JJs consisting of NbN/AlN/NbN tri-layers are highly attractive candidates as an alternative material technology for superconducting quantum circuits. This is because such epitaxially grown nitride JJs have great potential to solve material-related concerns, including the TLS problem, owing to their high crystal quality and chemical stability against oxidation. Moreover, due to the large superconducting gap (\(2\varDelta\) ~5.2 meV) and relatively high transition temperature (~16 K) of NbN21, quasiparticle excitation can be suppressed. One point that requires attention when using an AlN tunnel barrier is its piezoelectric property, i.e., the coupling between the electric field concentrated at the JJ and the underlying crystal lattice, which leads to substantial qubit decoherence via phonon emission22. In previous studies of phase qubits using an amorphous AlN barrier, energy relaxation times were as short as ~10 ns due to piezoelectricity23,24. However, the detrimental piezoelectric effect can be avoided when the AlN barrier is grown epitaxially in the cubic phase because of its lattice-inversion symmetry. In an early attempt with epitaxially grown cubic-phase AlN tunnel barriers25, longer relaxation times of 500 ns were observed in transmon qubits consisting of fully epitaxial NbN/AlN/NbN JJs on a single-crystal MgO substrate, commonly used because it allows good lattice matching between the materials. These coherence times were limited by the dielectric loss from the MgO substrate rather than the intrinsic properties of the NbN-based JJs themselves. In the context of NbN-based qubits, it is worth mentioning that an early report of a phase qubit using an epitaxially grown \(10\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{m}}}}}}\)-size NbN/AlN/NbN JJ also showed a relatively long phase coherence time of about \(5\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\)26. It has been characterized using a direct current (DC) readout so that the phase qubit is quite insensitive to the dielectric loss of substrate, which explains the relatively long coherence times obtained in that work.

Yet, the development of NbN-based qubits is still inadequate despite the superior properties of NbN as an alternative material for superconducting quantum hardware. More research is required in this direction to go beyond conventional Al-based qubits.

In this article, we report a significant improvement in quantum coherence of an epitaxially grown NbN-based superconducting qubit. To suppress the dominant dielectric loss from the MgO substrate, which has limited the energy relaxation time (\({T}_{1}\)) in the previous work25, we adopted a silicon (Si) substrate with a TiN buffer layer for epitaxial growth of NbN/AlN/NbN junctions27. The loss tangent of the high-resistivity Si substrate is much lower than that of MgO, as reported in ref. 28 (\(5\times {10}^{-6}-12\times {10}^{-6}\) for the former and \(0.5\times {10}^{-4}-0.8\times {10}^{-4}\) for the latter). Additionally, for the qubit design, we employed the structure of a capacitively shunted (C-shunt) flux qubit, which brings several advantages such as enhanced coherence and reproducibility as well as higher anharmonicity compared to transmon qubits29,30,31. With these modifications, we achieved coherence times as long as tens of microseconds using an all-nitride qubit with epitaxial JJs on a Si substrate. These coherence times are more than an order of magnitude longer than those obtained with qubits grown on MgO substrates. We explain that this improvement in coherence times can be attributed mainly to the reduced dielectric loss when replacing the MgO substrate with the Si substrate. These results shed light on the role of alternative material technologies in improving superconducting quantum circuits

Results and discussions

All-nitride C-shunt flux qubit

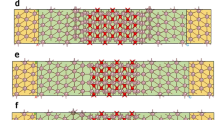

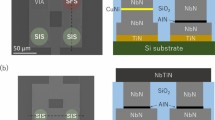

Our circuit is made of epitaxially grown NbN with a TiN buffer layer on a Si substrate. It consists of a C-shunt flux qubit that is based on epitaxial NbN/AlN/NbN JJs and is capacitively coupled to a half-wavelength superconducting coplanar waveguide resonator (CPW) (see Fig. 1). A detailed experimental setup together with device parameters are found in the Methods.

a a photograph of the qubit chip mounted into the sample package, b Laser scanning microscope image of the capacitively shunted flux qubit coupled to a half-wavelength (\(\lambda\)/2) CPW resonator made of NbN/TiN on a Si substrate. The inset shows a magnified image of a false-colored flux qubit structure with three NbN/AlN/NbN Josephson junctions (marked as JJ1, JJ2, and JJ3). c Scanning electron microscopy images corresponding to the three JJs taken after the qubit measurements. d The thickness profile of qubit taken from the laser scanning microscope system. The displayed scales are in \(\mu\)m. e Cross-sectional schematics of the part indicated by the blue star and dashed line in b. The JJ parts are marked by the orange dotted ellipses.

Spectroscopy of resonator

First, we assess the resonator properties as shown in Fig. 2a. The resonator’s transmission parameter (\({S}_{21}\)) is plotted as a function of the probe frequency and the normalized flux bias \(\Phi /{\Phi }_{0}\), where Φ is the magnetic flux bias applied through the qubit loop and \({\Phi }_{0}\) is the superconducting flux quantum. The power applied to the resonator was −138 dBm, corresponding to the level of a single photon in the resonator. The resonator has a fundamental resonance frequency \({\omega }_{r}/2\pi =9.796\) GHz at the qubit flux bias point \(\Phi /{\Phi }_{0}=0.5\) and a loaded quality factor \({Q}_{L}=1.405\times {10}^{4}\) extracted from the full width at half maximum of the power spectrum fitted by a Lorentzian function with linewidth \(\kappa /2\pi =0.697\) MHz (Fig. 2b). An internal quality factor \({Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{int}}}}}}}}=2.72\times {10}^{5}\) can be obtained from the relation32 \({Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{int}}}}}}}}={Q}_{L}/(1-{10}^{-{{{{{\rm{IL}}}}}}/20})\), where IL = 0.461 dB is the insertion loss measured under careful calibration. The corresponding loss tangent of our NbN resonator fabricated on a Si substrate is \({{\tan }}\delta =1/{Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{int}}}}}}}}=3.68\times {10}^{-6}\), which is almost two orders of magnitude lower than that of the MgO substrate (i.e., \({{\tan }}{\delta }_{({{{{{{\mathrm{MgO}}}}}}})}=3.30\times {10}^{-4}\))33. On both sides of \(\Phi /{\Phi }_{0}=0.5\) flux bias in Fig. 2a, clear anticrossings are observed at the points where the qubit energy is equal to the resonator’s photon energy, and the vacuum Rabi splitting is found to be \({\sim}120\) MHz.

a Spectrum of resonator microwave transmission (S21) with varying probe frequency and normalized flux (\(\Phi /{\Phi }_{0}\)). b The line profile of the resonator’s spectrum at flux bias \(\Phi /{\Phi }_{0}=0.5\) with a Lorentzian fit (solid line). c Qubit spectra obtained using dispersive readout. The dashed line is a simulation curve for the qubit transition from the ground state to the excited state (\({\omega }_{01}/2\pi\)). The qubit transition frequency has a minimum value of 6.61 GHz at the flux-insensitive point.

Spectroscopy of qubit

The measured transition frequency between the qubit’s ground and first excited state (\({\omega }_{01}/2\pi\)) is shown in Fig. 2c. At the flux-insensitive point (i.e., \(\Phi /{\Phi }_{0}=0.5\)), the qubit has its minimum frequency, 6.61 GHz, which is detuned by \(({\omega }_{r}-{\omega }_{01})/2\pi =3.19\) GHz from the fundamental resonator mode. As shown by the dashed line in Fig. 2c, the qubit spectrum \({\omega }_{01}/2\pi\) is reproduced by simulations with fitting parameters such as the area ratio of the small JJ relative to the two larger JJs \(\alpha =0.358\), Josephson energy \({E}_{J}/h=140\) GHz (where \(h\) is the Plank constant, and the corresponding critical current density of the larger junctions in the qubit is 38.6 A cm−2), and charging energy \({E}_{C}/h=({e}^{2}/2{C}_{\Sigma })/h=0.244\) GHz. Here, the total qubit capacitance (\({C}_{\Sigma }\)) is 79.6 fF, which includes a shunt capacitance \({C}_{{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}}}\) = 52.8 fF and the total junction capacitance of the flux qubit \({C}_{{{{{{\rm{J}}}}}}}=26.8\) fF (the detailed parameters are also found in the Methods).

Energy relaxation time, \({{{{{{\boldsymbol{T}}}}}}}_{{{{{{\boldsymbol{1}}}}}}}\), and its temporal variation

Qubit coherence properties were obtained from time-domain measurements. At the flux-insensitive point, we measured the energy relaxation time (\({T}_{1}\)), Ramsey decay time (\({T}_{2}^{\ast }\)), and spin-echo coherence time (\({T}_{2}\)) by applying the corresponding control-pulse sequences (see the insets in Figs. 3a, 4a, b). The qubit’s excited state population is measured by a digitizer and ensemble-averaged over \(6.5\times {10}^{4}\) repetitions. The resulting signal is plotted as a function of the delay time (\(\tau\)) in Figs. 3 and 4. Figure 3a shows the data for energy relaxation, which is well fitted by an exponential decay function \({{\exp }}(-\tau /{T}_{1})\), giving \({T}_{1}=18.25\pm 0.91\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\). In addition, we repeated the \({T}_{1}\) measurement 100 times over a period of 33 hours to observe the \({T}_{1}\) fluctuations of our nitride qubit (see Fig. 3b). The obtained values range from \(8\) to \(20\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\), and the histogram of the \({T}_{1}\) data is well fitted by a Gaussian distribution with peak center \({\bar{T}}_{1}=16.3\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) and standard deviation \({\sigma }_{T1}=1.73\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) as shown in Fig. 3c. These value of \({T}_{1}\) are the highest among all-nitride qubits. Currently they are lower than those of Al-based C-shunt flux qubits coupled to two-dimensional resonators on Si substrates30 (showing \({T}_{1}\) = 55 \(\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\)). However, there is still room for improvements in a number of aspects to increase \({T}_{1}\) further, and the significant improvement over state-of-the-art all-nitride qubits is an important step in that direction.

a \({T}_{1}\) decay profile with an exponential fit (solid line) with \({T}_{1}=18.25\pm 0.91\;\mu\)s. The inset shows the pulse sequence for \({T}_{1}\) measurement consisting of a \(\pi\) pulse (having a Gaussian envelope) with a 40 ns duration at \({\omega }_{01}\) and a readout pulse with a 400 ns duration at \({\omega }_{r}\). b Multiple \({T}_{1}\) values obtained from 100 measurements performed over 33 h, which show the temporal stability of \({T}_{1}\). Here the error-bars correspond to the standard deviation calculated in the fitting of each decay profile. c Histogram of the \({T}_{1}\) values with a Gaussian fit with center value \({\bar{T}}_{1}=16.3\;\mu\)s and standard deviation \({\sigma }_{T1}=1.73\;\mu\)s (Solid line).

Time-domain measurements showing a Ramsey fringe signal with \({T}_{2}^{\ast }=3.33\pm 0.30\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) and b Hahn echo signal with \({T}_{2}=23.20\pm 5.21\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\). The pulse sequences for the measurements are shown in the insets. The pulse sequences include a \(\pi\) pulse with a 40 ns duration, \(\pi /2\) pulses with same duration but half the amplitude of the \(\pi\) pulses, and readout pulses with 400 ns duration. Here the driving frequency in both measurements is detuned by 5 MHz from the qubit frequency and each coherence time is determined by fitting with an exponentially decaying sinusoidal function. Statistical distributions of c the \({T}_{2}^{\ast }\) values and d the \({T}_{2}\) values with Gaussian fits (solid line).

The temporal variation of \({T}_{1}\) is usually explained by quasiparticle fluctuations30 and instability of TLS defects34,35. When compared to Al-based single-junction Xmon-type transmon qubits in ref. 35 (where \({T}_{1}\) histograms show rather broad Gaussian distributions with \({\sigma }_{T1} \sim 20 \%\) of \({\bar{T}}_{1}\), with parameters \({\bar{T}}_{1}=46.18\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) and \({\sigma }_{T1}=10.24\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) for one sample, and \({\bar{T}}_{1}=70.72\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) and \({\sigma }_{T1}=14.31\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) for the other sample), we found that the \({T}_{1}\) data of our nitride qubit show little temporal variation, \({\sigma }_{T1} \sim 10 \%\) of \({\bar{T}}_{1}\). Such a narrow Gaussian distribution is also observed in Al-based C-shunt flux qubits30 and discussed as an indication that quasiparticles did not strongly influence this device. We therefore believe that our nitride qubit is also not strongly affected by quasiparticles. The instances of large deviation in \({T}_{1}\) to lower values outside the Gaussian peak in Fig. 3c, i.e., the outliers, can be explained by weakly coupled TLS defects in the remaining silicon dioxide (SiO2) after buffered hydrogen fluoride (BHF) treatment in our fabrication process. To reach a quantitative understanding of the degree to which two-level system could be limiting the qubit coherence time, more experiments are needed. Such an investigation is beyond the scope of this work and could be the subject of future work.

Phase relaxation times, \({{{{{{\boldsymbol{T}}}}}}}_{{{{{{\boldsymbol{2}}}}}}}^{\ast }\) and \({{{{{{\boldsymbol{T}}}}}}}_{{{{{{\boldsymbol{2}}}}}}}\)

We have measured the coherence times for phase relaxation from Ramsey and spin-echo experiments as shown in Fig. 4. The signals, which oscillate at the detuning frequency \(\delta \omega =\left|{\omega }_{01}-{\omega }_{d}\right|/2\pi =5\) MHz (where \({\omega }_{d}/2{\pi }\) is the drive frequency), can be fitted by exponentially decaying sinusoidal functions with relaxation times \({T}_{2}^{\ast }=3.33\pm 0.30\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) and \({T}_{2}=23.2\pm 5.21\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) (see Fig. 4a, b). The \({T}_{2}^{\ast }\) and \({T}_{2}\) measurements are also repeated 100 times along with the \({T}_{1}\) measurements. The resulting histograms are shown in Fig. 4c, d. The observed values of \({T}_{2}^{\ast }\) are in the range \(1.2{-}4.4\) \({{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\), and the corresponding Gaussian fit has a center value \({\bar{T}}_{2}^{\ast }=3.25\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) and a standard deviation \({\sigma }_{T2\ast }=0.44\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\). The \({T}_{2}\) values, obtained by applying an additional \(\pi\) pulse between the \(\pi /2\) pulses to decouple low frequency noise, are remarkably higher and lie in the range \(14{-}41\) \({{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\). The obtained center value of the Gaussian distribution is \(\bar{{T}_{2}}=21.5\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\).

Main factors behind the enhanced coherence time

Compared with the NbN-based qubit epitaxially grown on a MgO substrate (\({T}_{1}\approx {T}_{2}\approx 0.5\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\))25, the obtained coherence times for the qubit on a Si substrate (\({\bar{T}}_{1}=16.3\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) and \(\bar{{T}_{2}}=21.5\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) as the mean values) represent a significant improvements, namely 32-fold increase in \({T}_{1}\) and a 43-fold increase in \({T}_{2}\). To support the argument that the substrate material is responsible for this improvement, we briefly discuss the predicted limit on the quality factor for the MgO substrate material. As reported in ref. 25, the predicted limit for the MgO substrate clearly appears in the internal quality factor of the resonator \({Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{int}}}}}}}} \sim 2.35\times {10}^{3}\). This value of \({Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{int}}}}}}}}\) gives a higher value of the loss tangent for the MgO substrate \({\tan }\delta \sim 1/{Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{int}}}}}}}} \sim 4.25\times {10}^{-4}\) compared to our result for the Si substrate, i.e., \({{\tan }}\delta =3.68\times {10}^{-6}\) with \({Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{int}}}}}}}}=2.72\times {10}^{5}\). By considering the capacitive loss with the participation ratio of the capacitance across MgO among the total capacitance \({P}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{MgO}}}}}}}} \sim\)15% and ignoring other losses such as in the junctions as discussed in ref. 25, the predicted limit of the quality factor of qubit (\(Q\)) on MgO substrate is estimated to be \(Q \sim {Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{int}}}}}}}}/{P}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{MgO}}}}}}}} \sim 1.5\times {10}^{4}\) giving the expected relaxation time \({T}_{1}=Q/({E}_{01}/h)\) ~ 480 ns for \({E}_{01}/h\) = 5 GHz. This limit on \({T}_{1}\) set by the dielectric loss in the MgO substrate is indeed comparable to the experimentally observed value of \({T}_{1} \sim 500\) ns.

We can use a similar calculation to estimate the expected quality factor of the qubit grown on a Si substrate. We first consider common sources limiting \({T}_{1}\), such as the participation ratio (related to the loss of each material), Purcell effect, and TLS dissipation. Since the Purcell effect limit on \({T}_{1}\) can be calculated as \([\kappa \times {g}^{2}/(\omega_{r}-{\omega }_{01})^{2}]^{-1}\approx 300\;{\upmu }{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) where \(g\) is the coupling strength between resonator and qubit (\(g/2\pi \approx 90\) MHz from the experimental data), our results are not limited by the Purcell effect and hence the radiative loss can be ignored. In terms of participation ratio, the overall quality factor of qubit \(Q\) is limited by contributions from electric field (capacitive loss: \(1/{Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{cap}}}}}}}}\)), current (inductive loss: \(1/{Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{ind}}}}}}}}\)), and radiative loss (\(1/{Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{rad}}}}}}}}\)) with the relation36 \(1/Q=1/{Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{cap}}}}}}}}+1/{Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{ind}}}}}}}}+1/{Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{rad}}}}}}}}\). In our qubit, the participation ratio of the capacitance across Si (\({P}_{{Si}}\)) to the total capacitance is about \(66.2 \%\) (\({C}_{S}/{C}_{\Sigma }=52.7{{{{{\rm{fF}}}}}}/79.6{{{{{\rm{fF}}}}}}\)). If we only consider dielectric (capacitive) loss (i.e., \(1/Q\approx 1/{Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{cap}}}}}}}}\)) and ignore other losses such as loss in the junctions, the quality factor of the qubit is expected to be \(Q{\approx Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{cap}}}}}}}}={Q}_{{{{{{{\mathrm{int}}}}}}}}/{P}_{{Si}} \sim 4.10\times {10}^{5}\), which gives the relaxation time \({T}_{1}={{{{{\rm{Q}}}}}}/({\omega }_{01}) \sim 9.88\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\). This is within a factor of two from the experimentally observed values. Therefore, we ascribe the improvement in \({T}_{1}\) (up to the order of tens of \({{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\)) to the dominant contribution from the reduced dielectric loss by replacing the MgO substrate with the Si substrate. The enhanced \({T}_{1}\) of our qubit due to this contribution also translates into an improvement of \({T}_{2}\) compared to that of ref. 25, since \(1/{T}_{2}=1/2{T}_{1}+1/{T}_{\varphi }\), where \(1/{T}_{\varphi }\) is the pure dephasing time (estimated to be 63 \({{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\)).

Final remarks

In order to study the potential of epitaxially grown nitride qubits for superconducting quantum circuits, we have successfully fabricated an all-nitride C-shunt flux qubit epitaxially grown on a Si substrate by utilizing the growth technique of a full-epitaxial NbN/AlN/NbN tri-layer, conventional photolithography with i-line stepper, reactive ion etching, and chemical mechanical polishing (CMP). By employing a Si substrate instead of a conventional MgO substrate in order to reduce the dielectric loss from the substrate, our nitride flux qubit has demonstrated a significant improvement in coherence times, such as \({\bar{T}}_{1}=16.3\;{{\upmu }}{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) and \({\bar{T}}_{2}\) = 21.5 μs, which are more than an order of magnitude longer than those reported in the literature using MgO substrates. We conclude that this improvement in coherence times can be attributed mainly to the reduced dielectric loss when replacing the MgO substrate with the Si substrate. In addition, \({T}_{1}\) shows little temporal variation, about 10% deviation from the mean \({\bar{T}}_{1}\), indicating that quasiparticles did not strongly influence this device. Although the \({\bar{T}}_{2}\) value of 21.5 μs is still far from the record value of 0.3 ms observed in conventional Al-based qubits15, there remains much room for improvement in the design and fabrication processes of nitride qubits. Considering the advantages of NbN-based superconducting quantum circuits with epitaxial tunnel barriers, our results demonstrate that all-nitride superconducting qubits epitaxially grown on Si substrates have great potential to provide the basis for realizing large-scale superconducting quantum circuits.

Methods

Fabrication of all-nitride superconducting qubit

Samples were fabricated by using epitaxial growth of NbN/AlN/NbN junctions on Si wafers with TiN buffers and planarization by CMP27,37. In brief the fabrication flow is as follows. (i) The NbN (200 nm)/AlN (~1.8 nm)/NbN (150 nm) tri-layers are epitaxially grown on a high-resistivity (>20 kΩ·cm) Si substrate with a TiN (50 nm) buffer layer by a dc-magnetron sputtering system. (ii) For the device patterning, we used conventional photolithography by an i-line stepper (Canon FPA-3030i5+) and reactive ion etching with CF4 or CHF3 gases. As the first pattern in the device fabrication, the JJ part is formed by etching the upper NbN and AlN layers. (iii) Then the resonator and capacitor patterns are made by etching the lower-NbN and TiN layers. (iv) This is followed by the deposition of a SiO2 film that serves as an isolating layer between the base and wiring layers of the qubit. (v) Then, a planarization process by CMP is carried out to achieve a stable contact hole between the submicron-size JJs and the wiring layer. (vi) After forming contact holes between the base electrode and the wiring layer, the 300 nm-thick NbTiN wiring layer is deposited by dc-magnetron sputtering and patterned. Here the NbTiN wiring layer is chosen because of its smaller superconducting gap (\({T}_{c}=14{-}14.5{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}\)) compared to that of NbN (~16 K) for the gap engineering so that non-equilibrium quasiparticles are trapped in the wiring layer and do not diffuse into the junction as pointed out in ref. 25. Since the amorphous SiO2 layer may contain unwanted TLSs, it is removed by etching with BHF just before measurement. From measurements of the current-voltage characteristics of test JJs fabricated on the same wafer as the qubits at 4.2 K, the Josephson critical current density \({J}_{c}\), was found to be 40–48 A/cm2. Additionally, we confirmed that there is no change in \({J}_{c}\) between before and after BHF etching of the SiO2 layer, indicating no damage in the JJs by BHF treatment37.

Device parameters

The fabricated qubit-resonator architecture is depicted in Fig. 1. Our qubit has three JJs, all with circular shapes. Two JJs (i.e., JJ2 and JJ3 in Fig. 1b)) were designed to have 1.08 μm diameters (using a mask size of 1.28 μm diameter and expecting a reduction of 0.2 μm after the fabrication process), and the third junction (JJ1 in Fig. 1b) was designed to have a 0.70 μm diameter (using a mask size of 0.9 μm diameter) to get a smaller area by a factor α of 0.42. The actual junction diameters after fabrication were 1.07 μm and 0.645 μm, giving the somewhat reduced ratio of \({\alpha }\,\) = 0.36 as confirmed by scanning electron microscopy images, shown in Fig. 1c.

The junction and shunt capacitances used in the simulation for the qubit energy spectrum are described in the following. The junction capacitances of NbN/AlN/NbN junctions (\(C\)) is calculated by the parallel plate capacitor model, i.e., \(C={\epsilon }_{r}{\epsilon }_{0}A/t\) where \({\epsilon }_{r}\) is the relative permittivity of AlN, \({\epsilon }_{0}\) is the permittivity of vacuum, \(A\) is junction area, and \(t\) is the thickness of insulator (1.8 nm of AlN, which is determined by transmission electron microscopy measurements). The capacitance of the larger junctions in the flux qubit is \(C=31.2\) fF and that of the smaller junction is \({\alpha }C\). The total junction capacitance of the flux qubit consisting of three junctions is estimated using the relation \({C}_{J}=(\alpha +1/2)C=26.8\) fF. The small junction is shunted by a shunt capacitance (\({C}_{{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}}}\)) formed by two rectangular NbN pads. We estimate \({C}_{{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}}}\approx\)52.8 fF by considering the same-design C-shunt capacitance fabricated on a sapphire substrate in ref. 30 (i.e., \({C}_{{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}}}\) = 51 fF) and the relative permittivity (\({\epsilon }_{r}\)) 11.5 for sapphire and 11.9 for Si substrates, since the capacitance is proportional to \({\epsilon }_{r}\).

Figure 1d gives additional information about the thickness profile of the qubit taken from the laser scanning microscope system. Figure 1e shows a cross-sectional schematic view of the qubit part indicated by the dashed line in the inset of Fig. 1b.

For the dispersive readout, the qubit is coupled to a half-wavelength (6.0 mm long) CPW resonator. The center conductor is 10 μm wide, separated from the lateral ground planes by a 6 μm gap, resulting in a wave impedance of the coplanar waveguide \(Z=\)50 Ω for optimal impedance matching with conventional microwave components.

Experimental setup

The qubit chip was mounted in a sample holder made of gold-plated copper (Fig. 1a), which is thermally anchored to the mixing chamber of a dilution refrigerator. For magnetic shielding, the sample holder is covered by a three-layer shield consisting of one aluminum-based superconducting and two μ-metal magnetic shields.

The resonator and qubits are characterized at a base temperature of ~10 mK in a dilution refrigerator. For characterizing the resonator, microwave transmission \({S}_{21}\) was measured using a vector network analyzer or a heterodyne setup using an IQ mixer and a digitizer. For spectroscopy and coherence measurements of the qubit, we used an additional microwave drive and a commercial analogue-to-digital converter38, so that the qubit state is readout dispersively via the resonator in a circuit QED architecture.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Nakamura, Y., Pashkin, A. & Tsai, J. S. Coherent control of macroscopic quantum states in a single-Cooper-pair box. Nature 398, 786–788 (1999).

Kandala, A. et al. Hardware-efficient variational quantum eigensolver for small molecules and quantum magnets. Nature 549, 242–246 (2017).

O’Malley, P. J. J. et al. Scalable quantum simulation of molecular energies. Phys. Rev. X 6, 031007 (2016).

Ofek, N. et al. Extending the lifetime of a quantum bit with error correction in superconducting circuits. Nature 536, 441–445 (2016).

Hu, L. et al. Quantum error correction and universal gate set operation on a binomial bosonic logical qubit. Nat. Phys. 15, 503–508 (2019).

Ma, Y. et al. Error-transparent operations on a logical qubit protected by quantum error correction. Nat. Phys. 16, 827–831 (2020).

Arute, F. et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 574, 505–510 (2019).

Kjaergaard, M. et. al. Programming a quantum computer with quantum instructions. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.08838 (2020).

Balance, C. J., Harty, T. P., Linke, M. M., Sepiol, M. A. & Lucas, D. M. High-fidelity quantum logic gates using trapped-ion hyperfine qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 06054 (2016).

Devoret, M. H. & Schoelkopf, R. J. Superconducting circuits for quantum information: an outlook. Science 339, 1169–1174 (2013).

Oliver, W. D. & Welander, P. B. Materials in superconducting quantum bits. MRS Bull. 38, 816–825 (2013).

Kjaergaard, M. et al. Superconducting qubits: current state of play. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 11, 369–395 (2020).

Barends, R. et al. Minimal resonator loss for circuit quantum electrodynamics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 023508 (2010).

Chang, J. B. et al. Improved superconducting qubit coherence using titanium nitride. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 012602 (2013).

Place, A. P. M. et al. New material platform for superconducting transmon qubits with coherence time exceeding 0.3 milliseconds. Nat. Commun. 12, 1779 (2021).

Martinis, J. M. et al. Decoherence in Josephson qubits from dielectric loss. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 210503 (2005).

McDermott, R. Materials origins of decoherence in superconducting qubits. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 19, 2–13 (2009).

Müller, C., Cole, J. H. & Lisenfeld, J. Towards understanding two-level-systems in armorphous solids: insights from quantum circuits. Rep. Prog. Phys. 82, 124501 (2019).

Oh, S. et al. Elimination of two level fluctuators in superconducting quantum bits by an epitaxial tunnel barrier. Phys. Rev. B 74, 100502(R) (2006).

Kline, J. S. et al. Sub-micrometer epitaxial Josephson junctions for quantum circuits. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 25, 025005 (2012).

Wang, Z. et al. High-quality epitaxial NbN/AlN/NbN tunnel junctions with a wide range of current density. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 142604 (2013).

Ioffe, L. B. & Geshkenbein, V. B. Helm, Ch. & Blatter, G. Decoherence in superconducting quantum bits by phonon radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 63, 057001 (2004).

Martinis, JohnM. Superconducting phase qubits. Quantum Inf. Process 8, 81 (2009).

Lisitskiy, M. P., Lisenfeld, J., Fistul, M. V. & Ustinov, A. V. NbN based superconducting Josephson phase qubit with AlN tunnel barrier. 2017 16th International Superconductive Electronics Conference (ISEC), IEEE, 1-3 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1109/ISEC.2017.8314216.

Nakamura, Y. et al. Superconducting qubits consisting of epitaxially grown NbN/AlN/NbN Josephson junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 212502 (2011).

Yu, Y., Han, S., Chu, X., Chu, S.-I. & Wang, Z. Coherent temporal oscillations of macroscopic quantum states in a Josephson junction. Science 296, 889–892 (2002).

Makise, K., Terai, H. & Uzawa, Y. NbN/AlN/NbN/TiN tunnel junctions on Si (100) substrate for superconducting devices. IEEE Trans. Appl. Sup 26, 1100403 (2016).

O’Connell, A. D. et al. Microwave dielectric loss at single photon energies and millikelvin temperatures. Appl. Phys. Letts. 92, 112903 (2008).

You, J. Q., Hu, X., Ashhab, S. & Nori, F. Low-decoherence flux qubit. Phys. Rev. B (Rapid comm.) 75, 140515(R) (2007).

Yan, F. et al. The flux qubit revisited to enhance coherence and reproducibility. Nat. Commun. 7, 12964 (2016).

Abdurakhimov, L. V., Mahboob, I., Toida, H., Kakuyanagi, K. & Saito, S. A long-lived capacitively shunted flux qubit embedded in a 3D cavity. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 262601 (2019).

Sage, J. M., Bolkhovsky, V., Oliver, W. D., Turek, B. & Welander, P. B. Study of loss in superconducting coplanar waveguide resonators. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 063915 (2011).

Qiu, W., Makise, K., Terai, H., Nakamura, Y. & Wang, Z. Measurement of quality factor and losses in superconducting microwave resonator integrated with NbN/AlN/NbN qubit circuit. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 507, 042032 (2014).

Klimov, P. V. et al. Fluctuations of Energy-relaxation times in superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 090502 (2018).

Burnett, J. J. et al. Decoherence benchmarking of superconducting qubits. npj Quantum Inf. 5, 54 (2019).

Geerlings, K. L. Improving coherence of superconducting qubits and resonators. Ph.D. Thesis, Yale University (2013).

Qiu, W. & Terai, H. Fabrication of deep-sub-micrometer NbN/AlN/NbN epitaxial junctions on a Si-substrate. Appl. Phys. Express 13, 126501 (2020).

Inomata, K., Yamamoto, T., Billangeon, P.-M., Nakamura, Y. & Tsai, J. S. Large dispersive shift of cavity resonance induced by a superconducting flux qubit in the straddling regime. Phys. Rev. B 86, 140508 (R) (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Japan Science and Technology Agency Core Research for Evolutionary Science and Technology (Grant No. JPMJCR1775), JSPS KAKENHI (JP19H05615), JST ERATO (JPMJER1601), and partially by MEXT Quantum Leap Flagship Programs (JPMXS0120319794 and JPMXS0118068682). T.Y. acknowledges the Program for Promoting the Enhancement of Research Universities, Nagoya University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed extensively to the work presented in this article. S.K., H.T., T.Y., and K.S. designed the experiment and analyzed the data. S.K., W.Q., and H.T. fabricated the samples and characterized the basic junction properties. K.I. performed the microwave measurement. F.Y., T.F., and S.A. supported to data analysis. S.K. wrote the manuscript with feedback from all authors. K.S. and H.T. supervised the whole project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Communications Materials thanks Mikhail Lisitskiy and John Wright for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Aldo Isidori. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S., Terai, H., Yamashita, T. et al. Enhanced coherence of all-nitride superconducting qubits epitaxially grown on silicon substrate. Commun Mater 2, 98 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-021-00204-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-021-00204-4

This article is cited by

-

High-quality superconducting α-Ta film sputtered on the heated silicon substrate

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Weak spin-flip scattering in Pd89Ni11 interlayer of NbN-based ferromagnetic Josephson junctions

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Path toward manufacturable superconducting qubits with relaxation times exceeding 0.1 ms

npj Quantum Information (2022)

-

Towards practical quantum computers: transmon qubit with a lifetime approaching 0.5 milliseconds

npj Quantum Information (2022)

-

Hexagonal boron nitride as a low-loss dielectric for superconducting quantum circuits and qubits

Nature Materials (2022)