Grounding Ocean Ethics While Sharing Knowledge and Promoting Environmental Responsibility: Empowering Young Ambassadors as Agents of Change

- 1Department of Earth System Science and Environmental Technologies, National Research Council of Italy, Rome, Italy

- 2Institute for the Electromagnetic Remote Sensing of the Environment, National Research Council of Italy, Milan, Italy

- 3Institute of Oceanography, Hellenic Center for Marine Research, Athens, Greece

- 4Institute of Marine Biological Resources and Inland Waters, Hellenic Center for Marine Research, Athens, Greece

Actions addressing youths and marine science for “ambassadorship” are increasingly implemented via dedicated programs at the European and global level within the relevant policy frameworks, as a way for fostering the exchange of knowledge and cross-fertilizing practices among the Countries and basins. These programs are conceived to address the future generations of scientists, entrepreneurs, policymakers, and citizens, and to promote the awareness and shared responsibility on the sustainable use of marine resources in an authentic and credible way, through the empowerment of young researchers and professionals, communicators, or activists. Thus, such ambassadors are well-positioned to act as agents of change, improving the dimension of Ocean Ethics related to inclusive governance, especially necessary for an equal, just, and sustainable management of multi-actor and transboundary socio-environmental contexts. Pivoting on the Young Ambassadors' Program developed in the framework of the BlueMed Research and Innovation (R&I) Initiative for blue jobs and growth in the Mediterranean area as case practice, the article aimed to propose some reflections about the long-term perspective of such experiences. Outlining an emerging physiognomy of the “One Ocean Ambassadors,” it discusses their potential to build the next generation of responsible scientists, citizens, and decision-makers and to embed ethical principles in research-based marine governance. In addition, it addresses process-related elements, such as balancing advocacy and ethics and reflecting on the role of science communication. To further consolidate this practice, this article finally seeks to incorporate the intercultural aspects to connect the local to the global dimension toward a sustainable and value-based ocean governance.

Introduction

The ocean is necessary to the health and well-being of Earth and humans. It is an essential regulator of climate and life, providing vital goods and services and contributing to the socio-economic prosperity of coastal communities [(Avelino, 2017; The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2019; Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), 2020)]. In the last few decades, the sustainability of marine ecosystems has been posed at risk, due to the cumulative impacts of multiple anthropogenic stressors and to dramatic impact of climate change (Andersen et al., 2020; O'Hara et al., 2021; Vassilopoulou, 2021).

To underline the importance of science in developing reliable knowledge on the still poorly understood functioning of the oceans and the human-ocean interaction (Brennan et al., 2019) and provide evidence-based information to respond to the global challenges, the United Nations declared the years from 2021 to 2030 as the Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development1. Deployed as a common framework to ensure that ocean science can fully support countries to achieve the 2030 Agenda (United Nations (UN), 2015), the initiative calls for international cooperation of multi-stakeholders to address the priority social outcomes.

When dealing with improving participation and building inclusive governance, outlining processes is not less important than defining concepts: we propose in this study our experience and reflections on the engagement of the BlueMed Young Communication Ambassadors, describing the value of including societal actors as an important way to integrate ethical aims in research-led initiative oriented to promote a sustainable blue economy, building shared stewardship of the sea. The potential of young ambassadors to boost knowledge circulation and to raise awareness around the Mediterranean area has determined our observation that they can actually become agents of change, promoting environmental responsibility. We also propose a preliminary outline physiognomy of the “One Ocean Ambassadors,” emerging from the networking and synergies ongoing among the current programs and oriented to address the challenges of all the basins as interrelated natural and socio-political environments.

The Mediterranean has been for millennia at the heart of human cultures. However, a coherent, shared, sustainable, and knowledge-driven operational plan targeting the maritime activities was never promoted until 2014, when BlueMed, the intergovernmental R&I Initiative for blue jobs and growth in the Mediterranean area, implementing the European Blue Growth Strategy [(European Commission (EC), 2012)], developed a shared framework, resulting in the co-design of a Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda [(European Commission ad hoc advisory group of the BLUEMED Initiative (EC), 2015)].

The adoption of a holistic, trans-disciplinary, and inclusive approach constituted the core of this science-to-policy initiative, which intensively engaged stakeholders across the basin. In this vision, citizens are recognized to have a right to participate in the management of the “commons” (Vogler, 2012), i.e., common goods and services like those offered by the Mediterranean Sea, where conflicting uses of shared spaces and resources are likely to arise. BlueMed has built a network of actors, enabling national and inter-national policy-related dialogues via dedicated platforms to connect the shores of the basin. The youths were specifically addressed by the innovative Young Ambassadors' Program, aimed at sharing the BlueMed vision while building the next generation of marine science diplomats.

Dedicated Frameworks for Young Ambassadors and Ocean Science: Placing Ethics

Global mobilizations promoted by, or involving, young people standing up against the systematic inability of societies to address the climate crisis and other environmental issues, have had in recent years a new rise, e.g., the Fridays for Future global movement2. Not only they can push the claims higher in public policy debate, but also trigger a rethinking in the researchers and educators about the features and types of knowledge that are necessary, in formal and informal contexts, to tackle these inherently transdisciplinary, multi-interests challenges.

These mobilizations call for a paradigm change to frame economic and technological pressures in a sustainable, equitable, and prosperous picture, showing that reflections and public debate on ethical human-environment interplay cannot be further postponed.

From the perspective of a practitioner, we define ethics in this context as a living reflection on the values and principles guiding the conduct of humans. Analogously, we refer to Ocean Ethics as the ethics of human interplay with marine environments, both at individual and collective levels.

Complementing and integrating the approaches to the ethics of research and specifically of marine observation [as shown in UNESCO, 1999a,b; European Commission (EC), 2005; Owen et al., 2012; Avelino, 2017; Barbier et al., 2018; L'Astorina and Di Fiore, 2018], our perspective on Ocean ethics concentrates on the dimensions dealing with the principles driving collective behaviors, which are particularly relevant when multi-actor, transdisciplinary, and transboundary issues are involved and shared decisions are at stake, as in the case of marine environments. Specifically, we frame Programs of the ambassadors in the development of more inclusive governance of the common marine environments, basing on reflexive and balanced incorporation of scientific knowledge.

Academic reflection has underlined the relevance and delicacy of the knowledge-deliberation interface (e.g., Jasanoff, 2005; Fricker, 2007) and has suggested the need for widening societal inclusion, especially when dealing with issues at the intersection of different disciplinary visions and involving the interests, expectations, and concerns of diverse social groups. Moreover, enlarging the community of actors collaborating in the construction of knowledge is deemed necessary to improve the quality of knowledge itself and its social robustness (Funtowicz and Ravetz, 1993; Gibbons et al., 1994).

Transdisciplinary research can allow for knowledge co-creation and exchange, as well as social learning, including in the marine realm (Wehn et al., 2018; López-Rodríguez et al., 2019), enabling the formation of networks of stakeholders, and strengthening institutional frameworks. However, to be genuinely oriented to societal inclusion, a knowledge-based approach to the management of marine resources needs to be anchored to a shared governance (Kooiman et al., 2005), designed to be suitable to socio-ecological systems (Barbier et al., 2018). Effective institutional management should be based on inclusive, participatory decision-making, in which all actors are represented, and the awareness of relevant scientific evidence is complemented with broad ethical principles (Thompson, 2012). The integration of ethical values, transparency and social justice in practices and norms are necessary to balance processes involving multiple interests. This integrated approach can also pave the way towards effective, transparent and inclusive planning and management of human interactions with marine ecosystems (Morf et al., 2021), as also recognized by the ecosystem-based management approach (Cormier et al., 2017).

The key to the integration of scientific knowledge in plural socio-political arenas is a reflexive communication of scientific contents, aware of the debate on the societal value and orientation of science, and being able to stimulate a critical, value-based, public discourse on science and society (Davies, 2020).

Inclusive governance and reflexive science communication constituted the core of the activities of BlueMed Young Ambassadors. The BlueMed Ambassadors' Program experimented with new processes to engage young people, with particular emphasis on the key environmental problems of the Mediterranean Sea, promoting their civic roles, empowering them with up-to-date and transdisciplinary scientific reflections, and engaging them in the decision-making process.

The Mediterranean young ambassadorship is not a single case. The programs of marine ambassadors specifically focusing on the different basins and/or encompassing a European and global dimension have been developed in recent years: among others, the All-Atlantic Youth Ambassadors3; the Black Sea Young Ambassadors4; the European Marine Board (EMB) Young Ambassadors5; and the United Nation Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization/Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (UNESCO/IOC) Early Career Ocean Professionals (ECOPs)6.

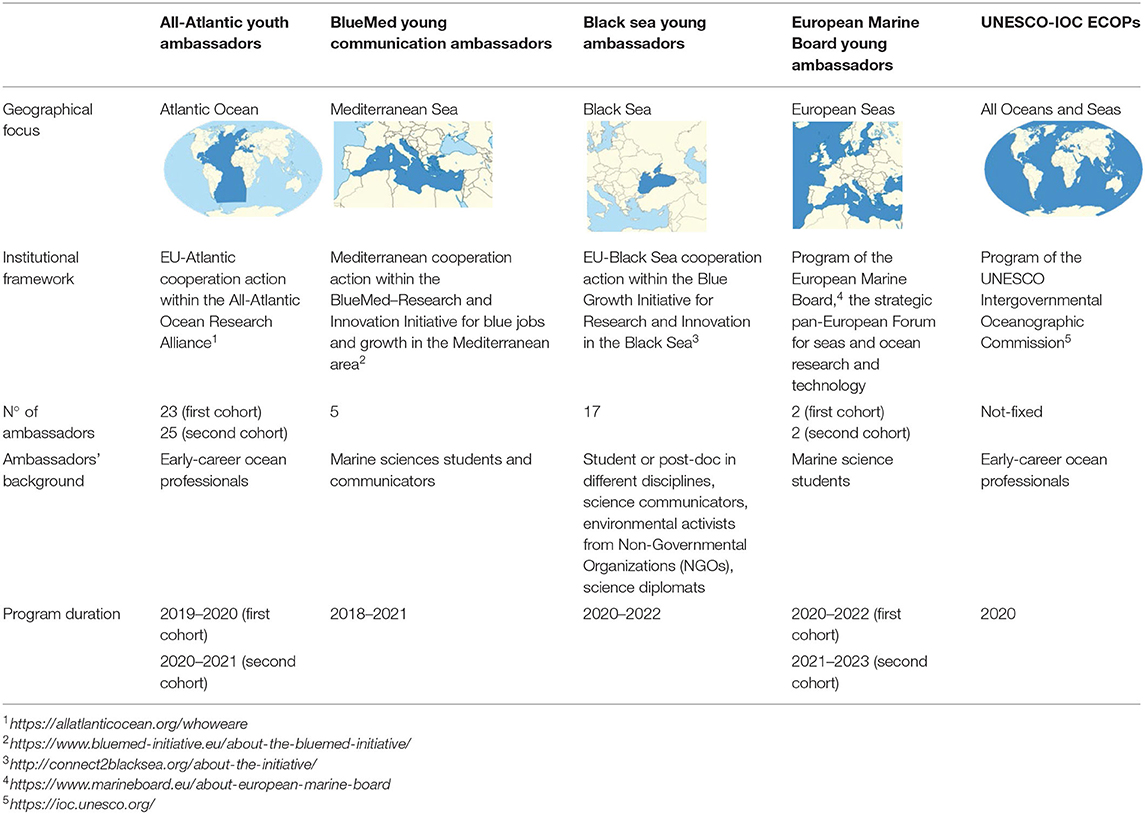

These programs focus on the different geographic areas and are anchored to diverse institutional frameworks (Table 1), but share; however, they have in common a super-national approach and an awareness-raising breath. All the programs valorize the networking of ambassadors as all citizens of One Ocean (Wilcox and Aguirre, (2004)), sharing sustainable behaviors and reinforcing the bonds between the ocean, conceived as an entity per se and not just as a void space among lands, and the citizens (Alexander et al., 2019). Thus, they support the development of Ocean ethics. They embody the connection between high-level knowledge-based political initiatives/organizations and the engagement and mobilization floor of citizens. In doing so, their actions regularly build on the ethical core of a collective assumption of responsibility for the common Ocean.

Looking at the increasing number of initiatives dedicated to young marine ambassadors for advocating a specific blue vision in the “One Planet One Ocean” framework, Table 1 proposes a synoptic view of a selection of programs of ambassadors targeting marine science and youth empowerment, presented by geographical focus, institutional framework, number and disciplinary background of ambassadors and duration of a program. In the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and the Black Sea, the programs are pivotal for supporting European internationalization strategies, fostering scientific cooperation across borders, and promoting the respect of fundamental values and principles [(European Commission (EC), 2021; Polejack et al., 2021)]; EMB Ambassadors stemmed within the leading European think tank in marine science policy and are engaged to promote marine science and EMB activities; ECOPs have a central role in designing and implementing the activities of the global UN-Decade of Ocean Science. These programs have been selected for the scope of the present article due to their common approach, as well as considering the networking action by the BlueMed Initiative for developing synergies, as explained next. Though, the assessment is not assumed to be exhaustive7.

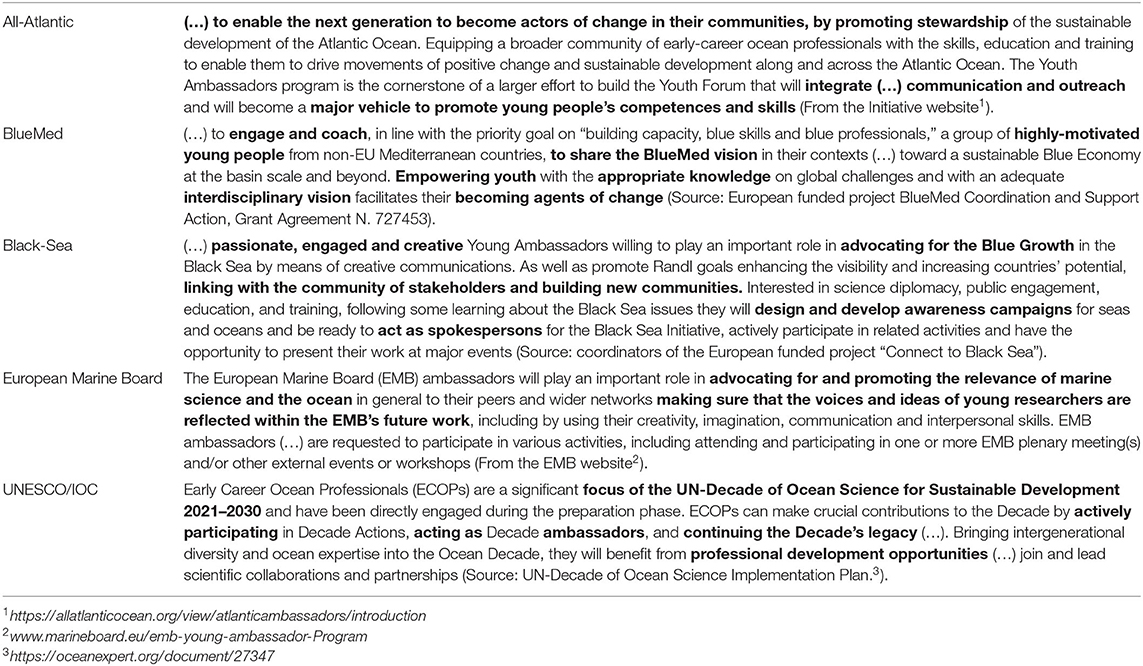

An initial set of value-based commitments for Ocean ethics shared by the programs emerges from the descriptions that each organization provides for promoting the engagement of the ambassadors (Table 2). Although different in size and geographical scope, they share the objectives of enabling change and building the next blue generation, as well as of fostering peer-to-peer networking and of facilitating local-to-global communication, leveraging on agile use of social media, and supporting travels and participation to international events. On the other side, building future citizens and empowering youth in contributing to co-designing strategic activities appears explicitly described only in some cases, while in others it is considered rather an impact or legacy of the ambassadorship action itself.

Table 2. Description of the ambassadors' programs published on the websites of home institutions or in official documents (in a single case in which a description was not publicly available, the authors report the exchanges with the Program coordinator).

Figure 1 sketches the features emerging from the synoptic view of the programs, enabling to draw a preliminary outline of the future “One Ocean Ambassadors,” stemming from the acknowledgment of the interrelation of all the basins and possibly arising from the promising synergies ongoing among the programs. The young ambassadors are mainly students or early-career professionals aged 20–35 years, coming from marine sciences but also from science communication, science diplomacy, or environmental activism; they are network builders and creative and skillful users of communication means, able to effectively raise the shared public awareness on critical issues and behaviors. They are trained on up-to-date science, with a focus on inter and transdisciplinarity, enabling them to frame the scientific knowledge base in the complex socio-ecological and political context. They are called to act in the responsibility roles (spokespersons, organizers of the events, and leaders of movements), achieving an impact on an international level. In terms of driving core values, these programs ground their activities on intergenerational diversity, cultural exchanges, wide and equal inclusion of all concerned voices (scientists, citizens, stakeholders), assumption of responsibility over the sustainable use and management of the Ocean resources, and respect for human and non-human environments.

Figure 1. The physiognomy of the “One Ocean Ambassadors” emerging from the comparison of current marine ambassadors programs.

The Case of the BlueMed Young Communication Ambassadors' Program

The signature of the Valletta Declaration in 2017 (Malta EU 2017, 2017), during the Malta Presidency of the EU Council, marked the enlargement of the BlueMed Initiative toward non-European Mediterranean countries and their full engagement into the activities. Among the enlargement actions that have been developed to ensure sharing of the BlueMed vision in such contexts, the BlueMed Young Ambassadors' Program8 was deployed as a tool of science diplomacy oriented to facilitate international science cooperation and improve international relations (The Royal Society, 2010) to finally consolidate the dialogue across all shores of the Mediterranean Basin.

The objective of the program was to engage and coach a group of highly motivated young people from non-EU Mediterranean countries, to share the BlueMed vision in their contexts, and set the grounds for the development of a pan-Mediterranean network of “BlueMed Ambassadors,” aiming to promote the research-based approach for a sustainable blue economy at the Mediterranean scale and beyond. Following a gender-balanced selection from a group of candidates proposed by the delegates of non-EU Mediterranean countries, five youths from Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, and Turkey were appointed as BlueMed Young Communication Ambassadors.

The first step of their involvement was a training event held in Barcelona in 2019 at the Union for the Mediterranean premises, where they could exchange experiences and visions and be taught on the BlueMed priorities (Trincardi et al., 2021). In coordination with the BlueMed Pilot action for a Healthy Plastic-free Mediterranean Sea9, marine litter was chosen as a thematic special focus. This global challenge requires indeed urgent cooperation, not only among the governmental bodies but also among stakeholders and coastal communities. The training was not limited to the scientific perspective, but it was conceived to be markedly interdisciplinary, including high-quality sessions on science diplomacy and science communication. Informal gatherings and non-mediated interactions, including via social media groups, proved as beneficial to build and consolidate collaboration and trust, and possibly foster the circulation of ethical values and perspectives.

Indeed, the focus on reflexive communication was a distinctive trait of the program, especially in conjunction with the transnational perspective offered by the science diplomacy frame. Thanks to the involvement of science communication researchers, the ambassadors could be acquainted with the basis of the contemporary vision on science communication, overcoming the severe limits posed by the traditional top-down approach, based on an incomplete vision of the public (L'Astorina and Valente, 2011). The Responsible Research and Innovation frame (RRI) (Ferri et al., 2018) was another important conceptual reference, and relevant participative methods were showcased (e.g., MARINA project10, Sea Watchers platform11). The actions of ambassadors were shaped accordingly: not only aimed at amplifying and diffusing the BlueMed concepts but including also local knowledge and expectations in a perspective of cultural reciprocity. In particular, communication was not intended solely as a powerful technical Ocean Literacy12 means to advocate for BlueMed and raise awareness, but as a fundamental network-building instrument, able to offer the public a more multi-faceted perception of science, possibly contributing to a higher democratization of knowledge and, hence, to a higher quality of public engagement.

The mandate of ambassadors was structured around the development of actions targeted to explore the complex political, socio-economic, cultural, and behavioral dimensions of the marine litter problem, from prevention to mitigation and removal, with the final aim of achieving a real change, from the environmental regulations and policies to the shared awareness of the stakeholders and citizens, to the practices of the Mediterranean coastal communities. Beach clean-ups, educational initiatives, and communication campaigns focused on the need to cut down plastics waste: all actions were planned in relation to country-specific or local contexts, under the common theme of “pollution needs no visa.” The motto was chosen by the ambassadors themselves, also echoing some of the difficulties they experienced in participating in the activities (e.g., due to VISA needs!), and underlining how anthropogenic litter—differently to people—can travel and reach anywhere without permit.

The ambassadors were able to link the local with the global dimensions, embracing the slogan “think globally act locally” which is pertinent to all global challenges, from climate change to marine litter. They succeeded in developing campaigns, able to speak in local contexts while retaining the complexity of the musings shared among the international community of scholars and practitioners (Vassilopoulou et al., 2021). For example, the Tunisian BlueMed Young Ambassador produced a short video documentary on the shift from traditional fishing practices to single-use plastic traps and on its environmental and socio-economic impact on the Kerkennah Archipelago community13. The Ambassador interviewed local handcrafters and involved voices of different generations, finally opening viable options to revert the path toward sustainability. The video was shot in Arabic and French, with English subtitles, for reaching local and international communities. The Turkish and the Algerian Ambassadors supported the production of video clips showing how the human plastics-based economy and related behaviors affect the underwater world14, to be disseminated locally (e.g., on public transportations) as well as on social media. All the ambassadors were also active on the educational side, organizing workshops for children and students, and beach-cleaning campaigns geared to raise the environmental awareness of local communities.

Another structural pillar of the program was the active participation to design the international conferences and events where ambassadors were given the floor to share knowledge, experiences, and visions and build a network of exchanges with their peers.

Their involvement in the European Science Open Forum 2020 was framed as a story-telling conversation between them and high-profile policy and scientific officers from the EU Commission and delegates of the BlueMed initiative15.

The opening session of the BlueMed Conference “One Mediterranean: practices, results, and strategies for a common Sea”16 organized in 2021, represented the first edition of a cross-basin and global dialogue among Young ambassadors, linking the Mediterranean Sea shores, the European basins, and the global Ocean. The process through which actors gain the capacity to mobilize resources and institutions to achieve a goal the BlueMed Ambassadors (Avelino, 2017) autonomously organized and chaired the session, exchanging views with their peer ambassadors from other basins and programs and conducting the conversations toward the identification of possible synergies and cross-basins network building.

It is worth noting that although the COVID-19 pandemic restricted physical interactions, these remote events enabled successful exchanges with peers and the audience. Positive hints of how the ambassadors are interpreting their mandate and on the most significant advantages from participating in such programs were informally gathered after the BlueMed Conference: they valued it as an enriching science diplomacy experience, allowing to learn about the actual challenges, as well as to interact with all sectors of society; a valuable exchange of visions, where empowerment derives from the ability to exchange views and a powerful capacity of networking; an incubator of new ideas having the potential to arise and flow.

Discussion and Conclusions: Empowering Young Ambassadors as Agents of Change

The considered ambassadors' programs, although at different stages of maturity, show the emergence of a group of crosscutting ethical foundations inspiring the actions and visions of the involved youths. These includes the assumption of co-responsibility, the richness coming from intergenerational, cultural and geographic diversity, the importance of reaching and involving all concerned voices, an ecological vision of environmental respect and, most important, the assumption of collective responsibility over the sustainability of One Ocean as a global commons.

Establishing synergies among the young ambassadors' programs was recognized as an important future objective to emphasize the interrelation of basins for homogeneity and improve the impact of the ambassadors. However, to ground Ocean ethics, these initiatives need to be considered both as instruments of knowledge sharing/sustainability advocacy and as open.

Young and motivated people proved ready to act coordinately to improve inclusive governance and contribute to the socio-political, cultural, and behavioral change in the field of marine sustainability. Along with their mandate, the ambassadors succeeded in sharing their thoughts and perspectives with relevant policy officers and delegates at national, European, and intergovernmental levels, and their contributions were valorized as the voices of the future generation inheriting this Planet. In particular, the BlueMed Program especially fostered the awareness of ambassadors of the delicacy of the knowledge-society interface, as well as improved their science diplomacy and science communication skills. Such skills are flourishing also beyond their mandate, in the diverse contexts in which they have been invited to contribute.

An emerging physiognomy of the future “One Ocean Ambassadors” can be outlined from the reasoned comparison of selected programs, as depicted in Figure 1.

In our perspective:

- recognizing that marine citizenship requires an enhanced awareness of environmental issues as well as an understanding of the role of personal and collective behavior (McKinley and Fletcher, 2010), an inter- and trans-disciplinary training is a crucial attribute. This should include science studies, reflexive science communication, and science diplomacy in addition to ocean science, and promote a critical rethinking of paradigms and values as well as the adoption of environmentally friendly behaviors;

- the programs of ambassadors need to remain flexible to embrace cultural differences and interests but clearly define roles, goals, and mandates. As young ambassadors, in most of the cases, volunteer their time and effort, a clear win-win framework of activities should be established where both the ambassadors and the programs' managers are supported and motivated. Not only identified benefits would contribute to the positive outcome of the program, but also the ethical issues related to involving volunteers would be duly addressed.

- to take stock from these experiences and further consolidate the promising work of existing programs, while incorporating Ocean ethics, a necessary step will be improve the trans-boundary approach: a dedicated, institution-supported platform such as the Youth4Ocean Forum17 should represent the starting point to envisage a structured cluster of the One Ocean young ambassadors routinely contributing to the ocean governance, at the science-to-policy and society-to-policy interface;

- improved support from relevant national public bodies to international projects and fora involving young ambassadors would increase their impact;

- it is still unclear at what level the role of young ambassadors can contribute to governance processes. Nevertheless, under the umbrella of trans-border and multi-stakeholder governance framework, a science policy advocacy group enriched with the voices of motivated youths, able to connect the local and international levels in a balanced, holistic, and ethically informed perspective, has the potential to mobilize policy circles and communities to act change, in line with the UN 2030 Agenda [(United Nations (UN), 2015)], targeting, in particular, the Sustainable Development Goal 14 “Life below Water.”

We also underline that any view of the youths solely as “loudspeakers” of concepts developed elsewhere should be avoided since, as we have shown, trusted and empowered young ambassadors have the potential to pursue the paradigm change necessary to trigger the unprecedented socio-environmental challenges that contemporary society is facing.

The regular assessments and analyses, via surveys and informal conversations, integrating social science and humanities, need to be put forward as tools for setting up a coherent framework for actions, as well as a reflexive monitoring process, such as qualitative and quantitative indicators to benchmark activities, results, and impacts. Getting inspired by the inclusion of representatives from the 14 European Young Academies in the latest meeting of the European Commission official Group of Chief Scientific Advisors (Nature Editorial, 2021), we propose as a pilot indicator within R&I actions to measure how open decision making bodies are to youths. Potentially, this approach could be beneficial to consolidate the role of young ambassadors in the public policy debate.

In addition, efforts are needed to focus on the viable paths to further develop the integration of ethical core values in initiatives involving young ambassadors and to promote Ocean ethics as an explicit debate theme. At least three relevant ethics dimensions are indeed addressed within this article: towards future generations, for cooperation between countries, and towards the ocean as a whole.Thus, this approach would enable to build the next generation of scientists, citizens, and decision-makers, more aware of the complexity of the socio-economic, ecologic, cultural and political ocean-landscape, and equipped with adequate instruments to manage this complexity.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

MC, RG, and AL'A contributed to conception, design, and preliminary drafting of this perspective article. Based on the design and co-development of the BlueMed Young Ambassadors' Program and related activities in the framework of the BlueMed EU funded project, EK and VV contributed to relevant sections. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The activities of the BlueMed Ambassadors' Program described in this article have been developed within the BlueMed Coordinationa and Support Action, a project funded by the European Framework Program H2020 under GA n.727453.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Deniz Yapilcan, Fella Moulek, Mustafa Ghazal, Badr El Mahrad, and In8s Boujmil for their enthusiastic work and participation and for teaching us through their experiences, and Kalliopi Pagou from the Hellenic Center for Marine Research, co-developer of the BlueMed Young Communication Ambassadors' Program. The infographics were developed by RG on the basis of an icon by Don clark atlanta on Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AGender_neutral.svg. The maps were developed on the basis of the image by Aplaice on Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Atlantic_Ocean_in_the_world_(blue)_(W3)_(CWF).svg.

Footnotes

1. ^https://www.oceandecade.org/

2. ^https://fridaysforfuture.org/

3. ^https://allatlanticocean.org/view/atlanticambassadors/introduction#; Twitter account: @AtlanticYouth.

4. ^http://connect2blacksea.org/outreach/youth-ambassadors/; Twitter account: @BlackSeaYouth.

5. ^http://www.marineboard.eu/emb-young-ambassador-Program

6. ^Twitter account: @OceanDecadeECOP.

7. ^Mediterranean Youth Forum to empower the youth for regional cooperation.

8. ^http://www.bluemed-initiative.eu/the-young-communication-ambassadors/

9. ^http://www.bluemed-initiative.eu/pilot-action-on-a-healthy-plastic-free-mediterranean-sea/

12. ^https://oceanliteracy.unesco.org/?post-types=all&sort=popular

13. ^https://youtu.be/yTizuSeQyDg

14. ^https://youtu.be/8wY5bpxy9zc

15. ^https://youtu.be/xXaVG4LtR6M.

16. ^http://www.bluemed-initiative.eu/bluemed-final-conference/

17. ^https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/maritimeforum/en/frontpage/1484

References

Alexander, K., Liggett, D., Leane, E., Nielsen, H., Bailey, J., Brasier, M., et al. (2019). What and who is an Antarctic ambassador? Polar Rec. 55, 497–506. doi: 10.1017/S0032247420000194

Andersen, J. H., Al-Hamdani, Z., Thérèse Harvey, E., Kallenbach, E., Murray, C., and Stock, A. (2020). Relative impacts of multiple human stressors in estuaries and coastal waters in the North Sea–Baltic Sea transition zone. Sci. Tot. Environ. 704:135316. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135316

Avelino, F. (2017). Power in Sustainability Transitions: Analysing power and (dis)empowerment in transformative change towards sustainability, Environmental Policy and Governance, 27:505–520. doi: 10.1002/eet.1777

Barbier, M., Reitz, A., Pabortsava, K., Wölfl, A.-C., Hahn, T., and Whoriskey, F. (2018). Ethical recommendations for ocean observation. Adv. Geosci. 45, 343–361. doi: 10.5194/adgeo-45-343-2018

Brennan, C., Ashley, M., and Molloy, O. (2019). A system dynamics approach to increasing ocean literacy. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:360. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00360

Cormier, R., Kelble, C. R., Robin Anderson, M., Allen, J. I., Grehan, A., and Gregersen, Ó. (2017). Moving from ecosystem-based policy objectives to operational implementation of ecosystem-based management measures. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 74-1, 406–413. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsw181

Davies, S. R. (2020). An empirical and conceptual note on science communication's role in society. Sci. Commun. 43, 116–133. doi: 10.1177/1075547020971642

European Commission (EC) (2005). The European Charter for Researchers–The Code of Conduct for the Recruitment of Researchers. Available online at: http://www.europa.eu.int/eracareers/europeancharter (accessed August 2021).

European Commission (EC) (2012). Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee of the Regions, Blue Growth Opportunities for Marine and Maritime Sustainable Growth, COM(2012) 494 Final. Available online at: ec.europa.eu/maritimeaffairs/sites/maritimeaffairs/files/docs/body/com_2012_494_en.pdf (accessed July 2021).

European Commission (EC) (2021). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Global Approach to Research and Innovation Europe's Strategy for International Cooperation in a Changing World. Brussels, 18.5.2021 COM(2021) 252 final. Available online at: https://op.europa.eu/it/publication-detail/-/publication/41f4df56-b8aa-11eb-8aca-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed April 2021).

European Commission ad hoc advisory group of the BLUEMED Initiative (EC) (2015). BlueMed Research and Innovation Initiative for Blue Jobs and Growth in the Mediterranean Area. Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda, 16 September 2015. Available online at: http://www.bluemed-initiative.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Bluemed-SRIA_A4.pdf (accessed June 2021).

Ferri, F., Biancone, N., Bicchielli, C., Caschera, M.C, D'Andrea, A., et al. (2018). “The MARINA project: promoting responsible research and innovation to meet marine challenges,” in Governance and Sustainability of Responsible Research and Innovation Processes. Springer Briefs in Research and Innovation Governance (Cham: Springer). 71–81. Available online at: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-73105-6

Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) (2020). The State of Mediterranean and Black Sea Fisheries 2020. General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations.

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1–208.

Funtowicz, S., and Ravetz, J. (1993). Science for the post-normal age. Futures 25, 739–755. doi: 10.1016/0016-3287(93)90022-L

Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., and Trow, M. (1994). The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies. Newcastle upon Tyne: SAGE.

Jasanoff, S. (2005). Designs on Nature: Science and Democracy in Europe and the United States. https://www.google.com/search?sxsrf=ALeKk01QRPISLH5z4LyUyxoDDC__Sy70Wg:1629861262863&q=princeton+nj&stick=H4sIAAAAAAAAAOPgE-LUz9U3MMm1KDFR4gAxc7KKq7S0spOt9POL0hPzMqsSSzLz81A4VhmpiSmFpYlFJalFxYtYeQqKMvOSU0vy8xTysnawMgIAQZXAsFUAAAA&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjXm-ysmsvyAhUm4jgGHeheBIMQmxMoATAqegQINxAD Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kooiman, J., Bavinck, M., Jentoft, S., and Pullin, R. (2005). Fish for Life. Interactive Governance for fisheries. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

L'Astorina, A., and Di Fiore, M., (eds.). (2018). Scienziati in affanno? Ricerca e Innovazione Responsabili (RRI) in teoria e nelle pratiche. CNR Edizioni.

L'Astorina, A., and Valente, A. (2011). Communicating science at school: from information to participation model. Ital. J. Sociol. Educ. 3, 210–220. doi: 10.14658/pupj-ijse-2011-3-10

López-Rodríguez, M. D., Cabello, J., Castro, H., and Rodríguez, J. (2019). Social learning for facilitating dialogue and understanding of the ecosystem services approach: lessons from a cross-border experience in the alboran marine basin. Sustainability 11:5239. doi: 10.3390/su11195239

Malta EU 2017 (2017). Valletta Declaration on Strengthening Euro-Mediterranean Cooperation through Research and Innovation, 4 May 2017. Available online at: http://www.bluemed-initiative.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Declaration_EuroMed-Cooperation-in-RI_1772.pdf (accessed June 2021).

McKinley, E., and Fletcher, S. (2010). Individual responsibility for the oceans? an evaluation of marine citizenship by UK marine practitioners. Ocean Coast. Manag. 53, 379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2010.04.012

Morf, A., Caña, M., and Shinoda, D. (2021). Ocean Governance and Marine Spatial Planning: Policy Brief. Paris: Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission.

Nature Editorial (2021). A 21st-birthday wish for Young Academies of science. Nature 594:474. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-01677-6

O'Hara, C. C., Frazier, M., and Halpern, B. S. (2021). At-risk marine biodiversity faces extensive, expanding, and intensifying human impacts. Science 372, 84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.abe6731

Owen, R., Macnaghten, P., and Stilgoe, J. (2012). Responsible research and innovation: from science in society to science for society, with society. Sci. Public Policy 39, 751–760. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scs093

Polejack, A., Gruber, S., and Wisz, M. S. (2021), Atlantic Ocean science diplomacy in action: the pole-to-pole All Atlantic Ocean Research Alliance. HumanitSocSciCommun 8:52. doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00729-6

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2019). Global Warming of 1.5°C. Special Report, 2019. https://www.google.com/search?sxsrf=ALeKk03CDIzOrdt5vRwIkA9KSsIoyNmk_g:1629861213719&q=Geneva&stick=H4sIAAAAAAAAAOPgE-LQz9U3MC5PK1aCsCwNjLSMMsqt9JPzc3JSk0sy8_P084vSE_MyqxJBnGKrjNTElMLSxKKS1KJihZz8ZLDwIlY299S81LLEHayMAE4—RWAAAA&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjrubSVmsvyAhWK4jgGHT_wAS4QmxMoATA2egQIQBAD Geneva: IPCC.

The Royal Society (2010). New frontiers in science diplomacy, Navigating the changing balance of power RS Policy document 01/10. Available online at: https://royalsociety.org/~/media/royal_society_content/policy/publications/2010/4294969468.pdf (accessed August 2021).

Thompson, P. B. (2012). Sustainability: ethical foundations. Nat. Educ. Knowl. 3:11. Available online at: https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/sustainability-ethical-foundations-71373239/

Trincardi, F., Cappelletto, M., Barbanti, A., Cadiou, J. F., Bataille, A., Campillos, L., et al. (2021). BlueMed Implementation Plan, BlueMed Project Deliverable D2.10, February 2021. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4604715 Available online at: https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/sustainability-ethical-foundations-71373239/

UNESCO (1999a). Declaration on Science and the Use of Scientific Knowledge. Available online at: http://www.unesco.org/science/wcs/eng/declaration_e.htm (accessed August 2021).

UNESCO (1999b). Ethics and the Responsibility of Science. Available online at: http://www.unesco.org/science/wcs/backgrounds/ethics.htm (accessed August 2021).

United Nations (UN) (2015). Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1, 21 October 2021. Available online at: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed May 2021.)

Vassilopoulou, V. (2021). Climate Change and Marine Spatial Planning: Policy Brief. Paris: Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission.

Vassilopoulou, V., Kastanidi, E., Giuffredi, R., L'Astorina, A., and Pagou, K. (2021). Ambassadors of the BLUEMED D5.6. Ambassadors' Activities Report, BlueMed Coordination and Support Action GA 727453. Available online at: http://www.bluemed-initiative.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/D5.6_28_4_2021_with-annexes.pdf

Vogler, J. (2012). Global commons revisited. Glob. Policy 3, 61–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-5899.2011.00156.x

Wehn, U., Collins, K., Anema, K., Basco-Carrera, L., and Lerebours, A. (2018). Stakeholder engagement in water governance as social learning: lessons from practice. Water Int. 43, 34–59. doi: 10.1080/02508060.2018.1403083

Keywords: young ambassadors, Ocean ethics, Mediterranean Sea, Responsible Research and Innovation, governance, communication, youth empowerment

Citation: Cappelletto M, Giuffredi R, Kastanidi E, Vassilopoulou V and L'Astorina A (2021) Grounding Ocean Ethics While Sharing Knowledge and Promoting Environmental Responsibility: Empowering Young Ambassadors as Agents of Change. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:717789. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.717789

Received: 31 May 2021; Accepted: 16 August 2021;

Published: 17 September 2021.

Edited by:

Michelle Scobie, The University of the West Indies St. Augustine, Trinidad and TobagoReviewed by:

Anna Maria Addamo, European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), ItalyChiara Lombardi, Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development (ENEA), Italy

Copyright © 2021 Cappelletto, Giuffredi, Kastanidi, Vassilopoulou and L'Astorina. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Margherita Cappelletto, margherita.cappelletto@cnr.it

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Margherita Cappelletto

Margherita Cappelletto Rita Giuffredi

Rita Giuffredi Erasmia Kastanidi

Erasmia Kastanidi Vassiliki Vassilopoulou

Vassiliki Vassilopoulou Alba L'Astorina

Alba L'Astorina