Abstract

Purpose

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is the most frequent endocrinopathy in women of reproductive age. Machine learning (ML) is the area of artificial intelligence with a focus on predictive computing algorithms. We aimed to define the most relevant clinical and laboratory variables related to PCOS diagnosis, and to stratify patients into different phenotypic groups (clusters) using ML algorithms.

Methods

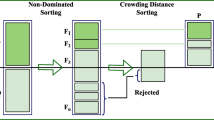

Variables from a database comparing 72 patients with PCOS and 73 healthy women were included. The BorutaShap method, followed by the Random Forest algorithm, was applied to prediction and clustering of PCOS.

Results

Among the 58 variables investigated, the algorithm selected in decreasing order of importance: lipid accumulation product (LAP); abdominal circumference; thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) levels; body mass index (BMI); C-reactive protein (CRP), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and insulin levels; HOMA-IR value; age; prolactin, 17-OH progesterone and triglycerides levels; and family history of diabetes mellitus in first-degree relative as the variables associated to PCOS diagnosis. The combined use of these variables by the algorithm showed an accuracy of 86% and area under the ROC curve of 97%. Next, PCOS patients were gathered into two clusters in the first, the patients had higher BMI, abdominal circumference, LAP and HOMA-IR index, as well as CRP and insulin levels compared to the other cluster.

Conclusion

The developed algorithm could be applied to select more important clinical and biochemical variables related to PCOS and to classify into phenotypically different clusters. These results could guide more personalized and effective approaches to the treatment of PCOS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Python programming language and scikit-learn Random Forest implementation (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/).

References

Meier R (2018) Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nurs Clin North Am 53(3):407–420

Azziz R (2018) Polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 132(2):321–336

Bozdag G, Mumusoglu S, Zengin D, Karabulut E, Yildiz BO (2016) The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod 31:2841–2855

Patel S (2018) Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), an inflammatory, systemic, lifestyle endocrinopathy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 182:27–36

Oh J, Lee J, Lee H, Oh Y, Sung Y, Chung H (2009) Serum C-reactive protein levels in normal-weight polycystic ovary syndrome. Korean J Intern Med 24(4):350–355

Hilali N, Vural M, Camuzcuoglu H, Camuzcuoglu A, Nurten A (2013) Increased prolidase activity and oxidative stress in PCOS. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 79(1):105–110

- National Institutes of Health (2012) Evidence-based methodology workshop on polycystic ovary syndrome. December 3–5. Executive summary. Final report. https://prevention.nih.gov/docs/programs/pcos/FinalReport.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2021

March W, Moore V, Willson K, Phillips D, Norman R, Davies M (2010) The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod 25(2):544–551

Sóter M, Ferreira C, Sales M, Candido A, Reis FM, Milagres K, Ronda C, Silva I, Sousa M, Gomes K (2015) Peripheral blood-derived cytokine gene polymorphisms and metabolic profile in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cytokine 76(2):227–235

Tosatti J, Sóter M, Ferreira C, Silva I, Cândido A, Sousa M, Reis FM, Gomes K (2020) The hallmark of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine ratios in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cytokine 134:155187

Carvalho L, Ferreira C, Sóter M, Sales M, Rodrigues K, Martins S, Candido A, Reis FM, Silva I, Campos F, Gomes K (2017) Microparticles: inflammatory and haemostatic biomarkers in polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol 443:155–162

Carvalho L, Ferreira C, Oliveira D, Rodrigues K, Duarte R, Teixeira M, Xavier L, Candido A, Reis F, Silva I, Campos F, Gomes K (2017) Haptoglobin levels, but not Hp1-Hp2 polymorphism, are associated with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Assist Reprod Genet 34(12):1691–1698

Xavier L, Sóter M, Sales M, Oliveira D, Reis H, Candido A, Reis FM, Silva I, Gomes K, Ferreira C (2018) Evaluation of PCSK9 levels and its genetic polymorphisms in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gene 644:129–136

Carvalho L, Ferreira C, Candido A, Reis FM, Sóter M, Sales M, Silva I, Nunes F, Gomes K (2017) Metformin reduces total microparticles and microparticles-expressing tissue factor in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Arch Gynecol Obstet 296(4):617–621

Sales M, Sóter M, Candido A, Fernandes A, Oliveira F, Ferreira A, Sousa M, Ferreira C, Gomes K (2013) Correlation between plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) promoter 4G/5G polymorphism and metabolic/proinflammatory factors in polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol 29(10):936–939

Xavier L, Gontijo N, Rodrigues K, Cândido A, Reis F, Sousa M, Silveira J, Oliveira F, Ferreira C, Gomes K (2019) Polymorphisms in vitamin D receptor gene, but not vitamin D levels, are associated with polycystic ovary syndrome in Brazilian women. J Gynecol Endocrinol 35(2):146–149

Reis G, Gontijo N, Rodrigues K, Alves M, Ferreira C, Gomes K (2017) Vitamin D receptor polymorphisms and the polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 43(3):436–446

Alves M, de Souza I, Ferreira C, Cândido AL, Bizzi M, OliveiraReisGomes FFK (2020) Galectin-3 is a potential biomarker to insulin resistance and obesity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol 36(9):760–763

Oliveira F, Mamede M, Bizzi M, Rocha A, Ferreira C, Gomes K, Cândido AL, Reis F (2019) Brown adipose tissue activity is reduced in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol 181(5):473–480

Rahul C (2015) Machine learning in medicine. Circulation 132(20):1920–1930

Saber H, Somai M, Rajah G, Scalzo F, Liebeskind D (2019) Predictive analytics and machine learning in stroke and neurovascular medicine. Neurol Res 41(8):681–690

Handelman G, Kok H, Chandra R, Razavi A, Lee M, Asadi H (2018) eDoctor: machine learning and the future of medicine. J Intern Med 284(6):603–619

Breiman L (2001) Random forests. Mach Learn 45(1):5–32

Lundberg M, Erion G, Chen H, DeGrave A, Prutkin J, Nair B, Katz R, Himmelfarb J, Bansal N, Lee S (2020) From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat Mach Intell 2(1):56–67

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group (2004) The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 81:19–25

Santos R (2001) III Diretrizes Brasileiras Sobre Dislipidemias e Diretriz de Prevenção da Aterosclerose do Departamento de Aterosclerose da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia. Arq Bras Cardiol 77(3):1–25

Tang Q, Xueqin L, Song P, Xu L (2015) Optimal cut-off values for the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and pre-diabetes screening: Developments in research and prospects for the future. Drug Discov Ther 9(6):380–385

Lwow F, Jedrzejuk D, Milewicz A, Szmigiero L (2016) Lipid accumulation product (LAP) as a criterion for the identification of the healthy obesity phenotype in postmenopausal women. Exper Gerontol 82:81–87

Keany E (2021) BorutaShap 1.0.15 2020. https://pypi.org/project/BorutaShap/. Accessed 26 May 2021

Kursa M, Rudnicki W (2010) Feature selection with the Boruta package. J Stat Softw 36(11):1–13

Bock H (2007) Clustering methods: a history of k-means algorithms. Selected contributions in data analysis and classification. Springer, Berlin, pp 161–172

Teede H, Misso M, Costello M, Dokras A, Laven J, Moran L, Piltonen T, Norman R, International PCOS Network (2018) Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 33(9):1602–1618

Pall M, Azziz R, Beires J, Pignatelli D (2010) The phenotype of hirsute women: a comparison of polycystic ovary syndrome and 21-hydroxylase-deficient nonclassic adrenal hyperplasia. Fertil Steril 94(2):684–689

Saadia Z (2020) Follicle stimulating hormone (LH: FSH) ratio in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) obese vs non- obese women. Med Arch 74(4):289–293

Speiser P, Knochenhauer E, Dewailly D, Fruzzetti F, Marcondes J, Azziz R (2000) A multicenter study of women with nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia: relationship between genotype and phenotype. Mol Genet Metab 71:527–534

Qiu L, Liu J, Hei Q (2015) Association between two polymorphisms of follicle stimulating hormone receptor gene and susceptibility to polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis. Chin Med Sci J 30(1):44–50

Deniz R, Yavuzkir S, Ugur K, Ustebay D, Baykus Y, Ustebay S, Aydin S (2021) Subfatin and asprosin, two new metabolic players of polycystic ovary syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol 41(2):279–284

Glintborg D, Altinok M, Mumm H, Buch K, Ravn P, Andersen M (2014) Prolactin is associated with metabolic risk and cortisol in 1007 women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 29:1773–1779

Yang H, Di J, Pan J, Yu R, Teng Y, Cai Z, Deng X (2020) The Association between prolactin and metabolic parameters in pcos women: a retrospective analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 11:263

Corona G, Wu F, Rastrelli G, Lee D, Forti G, O’Connor D, O’Neill T, Pendleton N, Bartfai G, Boonen S, Casanueva F, Finn J, Huhtaniemi I, Kula K, Punab M, Vanderschueren D, Rutter M, Maggi M, EMAS Study Group (2014) Low prolactin is associated with sexual dysfunction and psychological or metabolic disturbances in middle-aged and elderly men: the European male aging study (EMAS). J Sex Med 11(1):240–253

Wagner R, Heni M, Linder K, Ketterer C, Peter A, Bohm A, Hatziagelaki E, Stefan N, Staiger H, Häring H, Fritsche A (2014) Age-dependent association of serum prolactin with glycaemia and insulin sensitivity in humans. Acta Diabetol 51(1):71–78

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group (2004) Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod 19(1):41–47

Cupisti S, Haeberle L, Schell C, Richter H, Schulze C, Hildebrandt T, Oppelt P, Beckmann M, Dittrich R, Mueller A (2011) The different phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome: no advantages for identifying women with aggravated insulin resistance or impaired lipids. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 119:502–508

Mehrabian F, Khani B, Kelishadi R, Kermani N (2011) The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance according to the phenotypic subgroups of polycystic ovary syndrome in a representative sample of Iranian females. J Res Med Sci 16:763–769

Shroff R, Syrop C, Davis W, Van Voorhis B, Dokras A (2007) Risk of metabolic complications in the new PCOS phenotypes based on the Rotterdam criteria. Fertil Steril 88:1389–1395

Lizneva D, Suturina L, Walker W, Brakta S, Gavrilova-Jordan L, Azziz R (2016) Criteria, prevalence, and phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 106(1):6–15

Acknowledgements

FMR, AAV and KBG are grateful to CNPq for the research fellowship.

Funding

The grants from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: ISS, AAV, and KBG. Data curation: CNF, LBXC, MOS, LMLC, JA, MFS, ALC, and FMR. Formal analysis: ISS. Funding acquisition: KBG. Investigation: ISS, AAV, FMR, and KBG. Methodology: ISS and AAV. Project administration: KBG. Resources: KBG. Software: ISS and AAV. Supervision: AAV and KBG. Validation: ISS. Visualization: ISS. Roles/writing—original draft: ISS and KBG. Writing—review and editing: ISS, FMR, and KBG.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest or financial/personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

The Ethics Committee (COEP) of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) approved the study (CAAE 0379.0.203.000-11). We certify that the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Silva, I.S., Ferreira, C.N., Costa, L.B.X. et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome: clinical and laboratory variables related to new phenotypes using machine-learning models. J Endocrinol Invest 45, 497–505 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-021-01672-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-021-01672-8