Abstract

Foreignness has long been a central construct in international business research, with research streams examining its conceptualizations, manifestations, and consequences. Researchers started by taking foreignness to be a liability, then later considered the possibility of its being an asset. A still more recent view is that foreignness is an organizational identity that a firm can purposefully manage. Broadly conceived, foreignness is an umbrella construct that directly or tangentially covers research on country of origin, institutional distance, firm-specific advantages, and the ownership–location–internalization eclectic paradigm. We review the body of research on foreignness and track the evolution of its four streams, liability of foreignness, asset of foreignness, drivers of foreignness, and firm responses to foreignness. We call for a clearer conceptualization and a sounder theoretical grounding of the foreignness construct, more integration of the liability of foreignness and the asset of foreignness research streams, greater attention to the multiple strategies firms use to manage foreignness, and the extension of the field to less-explored contexts such as emerging economies, digitalization, and de-globalization.

Résumé

L'origine étrangère de l’entreprise (Foreignness) a longtemps été un construit central dans la recherche en affaires internationales dont divers courants examinent ses conceptualisations, ses configurations et ses conséquences. Les chercheurs ont commencé par considérer l'origine étrangère comme un handicap, puis, plus tard, envisagé la possibilité qu'elle soit un avantage. Une vision encore plus récente la considère comme une identité organisationnelle que l’entreprise peut gérer dans un but précis. Au sens large, l'origine étrangère est un concept global qui englobe directement ou indirectement les recherches portées sur le pays d'origine, la distance institutionnelle, les avantages spécifiques de l'entreprise et le paradigme éclectique propriété-localisation-internalisation. Nous passons en revue le corpus de recherche sur l'origine étrangère et suivons l'évolution de ses quatre courants, les handicaps liés à l’origine étrangère de l’entreprise (liability of foreignness), ses avantages, ses déterminants et les réponses associées de l’entreprise. Nous appelons à une conceptualisation plus claire et un fondement théorique plus solide du construit origine étrangère, à une intégration plus importante entre les deux courants de recherche portés sur les handicaps et les avantages liés à l’origine étrangère de l’entreprise, à une plus grande attention aux multiples stratégies des entreprises destinées à la gérer, et, enfin, à l'extension du champ de recherche aux contextes moins explorés tels que les économies émergentes, la numérisation et la dé-globalisation.

Resumen

La extranjería ha sido un constructo central en la investigación en negocios internacionales, con corrientes de investigación examinando sus conceptualizaciones, manifestaciones y consecuencias. Los investigadores comienzan a tomar la extranjería como una limitación (pasivo) y luego se consideró la posibilidad que fuera una ventaja (activo). Un punto de vista aún más reciente es que la extranjería es una identidad organización que una empresa puede deliberadamente gestionar. Ampliamente concebido, la extranjería es un constructo sombrilla que cubre directa o tangencialmente la investigación sobre el país de origen, la distancia institucional, las ventajas especificas de la empresa y el paradigma ecléctico de propiedad-localización-internacionalización. Revisamos el conjunto de investigaciones sobre extranjería y rastreamos la evolución de sus cuatro corrientes, la desventaja de extranjería, la ventaja de la extranjería, los impulsores de la extranjería y las respuestas de la empresa a la extranjería. Hacemos un llamado para una conceptualización más clara y una base teórica más sólida del constructo de la extranjería, una mayor integración de las corrientes de investigación sobre desventaja de extranjería y la ventaja de extranjería, una mayor atención a las múltiples estrategias que las empresas usan para gestionar la extranjería, y la expansión del campo a contextos menos explorados, como las economías emergentes, la digitalización y la desglobalización.

Resumo

Ser estrangeiro tem sido um construto central na pesquisa de negócios internacionais, com correntes de pesquisa examinando suas conceituações, manifestações e consequências. Pesquisadores começaram por considerar ser estrangeiro um passivo e, mais tarde, consideraram a possibilidade de ser um ativo. Uma visão ainda mais recente é que ser estrangeiro é uma identidade organizacional que uma empresa pode administrar propositalmente. Amplamente concebida, ser estrangeiro é um construto guarda-chuva que cobre direta ou tangencialmente a pesquisa sobre país de origem, distância institucional, vantagens específicas da empresa e o paradigma eclético de propriedade-localização-internalização. Revisamos o corpo de pesquisas sobre ser estrangeiro e rastreamos a evolução de suas quatro correntes, passivo de ser estrangeiro, ativo de ser estrangeiro, fatores de ser estrangeiro e respostas da empresa a ser estrangeiro. Pedimos uma conceituação mais clara e uma fundamentação teórica mais sólida do construto ser estrangeiro, mais integração das correntes de pesquisa do passivo de ser estrangeiro e do ativo de ser estrangeiro, maior atenção às múltiplas estratégias que empresas usam para gerenciar o ser estrangeiro, e a extensão do campo para contextos menos explorados, como economias emergentes, digitalização e deglobalização.

摘要

外来性长期以来一直是国际商务研究的一个核心概念, 研究流派研究了它的概念化、表现形式和影响。研究人员一开始将外来性视为劣势, 而后考虑它作为优势的可能性。一种更新近的观点认为, 外来性是公司可以有目的地进行管理的组织身份。从广义上讲, 外来性是一个伞状概念, 它直接或间接地涵盖了对原产国、制度距离、公司特定优势和所有权-地点-内部化折衷范式的研究。我们回顾了关于外来性的研究, 并跟踪了其四个流派的演变, 即外来性的劣势、外来性的优势、外来性的驱动因素和对外来性的企业反应。我们呼吁对外来性的概念更清晰的概念化和更完善的理论基础, 对外来性的劣势和外来性的优势的研究流派进行更多的整合, 更加关注公司用于管理外国性的多种策略, 并将该领域扩展到较少探索的例如新兴经济体、数字化和去全球化的情境之中。

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Foreignness is inherent to multinational enterprises (MNEs): its conceptualization, manifestations, and consequences are central to international business (IB) research. A subset of the overall costs of doing business abroad (Hymer, 1976) has been labeled the liability of foreignness (LOF), which hinges primarily on the social, relational, and institutional factors (Zaheer, 1995, 2002) that give rise to unfamiliarity, discrimination, and relational hazards for MNEs in their host countries (Eden & Miller, 2004). Since the seminal work of Zaheer (1995), the rigor and legitimacy of research on this topic has been enhanced by sizeable literature (for surveys see Luo & Mezias, 2002; Denk et al., 2012). Later research shows that, besides a liability, foreignness can be an asset (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999; Brannen, 2004; Sethi & Judge, 2009; Un, 2011; Mallon & Fainshmidt, 2017). The asset of foreignness (AOF) concept has provided a more balanced account of the impact and outcomes of foreignness (Sethi & Judge, 2009; Edman, 2016a; Mallon & Fainshmidt, 2017; Taussig, 2017; Siegel et al., 2019).

Nonetheless, concerns remain about the usefulness of the foreignness construct for theory building and testing in IB. For instance, is foreignness a binary or a continuous variable? Is it an objective country-pair level phenomenon (Zaheer, 1995; Mezias, 2002a; Eden & Miller, 2004) or a mostly subjective perception of a host country in the minds of managers (Edman, 2016a; Pant & Ramachandran, 2017)? Foreignness also has multiple manifestations which, we believe, can provide fine-grained contextual qualifications of the construct and of its consequences (cf. Eden & Miller, 2004; Sethi & Judge, 2009; Ramachandran & Pant, 2010). Some research streams are specific, e.g., that on the impact of MNE country of origin (Elango & Sethi, 2007; Ramachandran & Pant, 2010) and that on the institutional distance between MNE home and host countries (Eden & Miller, 2004; Salomon & Wu, 2012; Zhou & Guillén, 2015; Kostova et al., 2019), while others are more general, e.g., the ownership–location–internalization (OLI) paradigm (Dunning, 1980, 2000).

Due to differences in research objectives and theoretical perspectives, the different research streams have to a considerable extent been fragmented and incompatible, hindering conceptual clarification and theoretical development in foreignness research. We aim to provide a critical review of the various streams of foreignness research in IB, highlight the theoretical tensions and debates within each stream, and suggest potential avenues for cross-fertilization and integration.

Given that LOF research was the subject of a special issue in the Journal of International Management in 2002 and then systematically reviewed a decade later (Denk et al., 2012), we will keep our review on LOF research succinct and devote more attention to post-2012 publications. In our review of AOF research, we build on Mallon and Fainschmidt’s (2017) discussion of the theoretical grounding of AOF and examine its impact on innovation, its joint effect with LOF, and how the two can be simultaneously managed. We also compare and contrast prior research on drivers of foreignness, i.e., country of origin and institutional distance, with research on LOF and AOF, and disentangle their multifaceted relationship. Finally, we go beyond Denk et al. (2012) by including firm-level responses to foreignness, such as offsetting it with firm-specific advantages, mitigating it with organizational learning, overcoming it with market and non-market strategies, and managing it as identity (Edman, 2016a). At the end of our review of each stream, we summarize unresolved issues that call for further research.

REVIEW PROCESS AND OVERALL FRAMEWORK

Review Process

Our review spans 25 years, from 1995 to 2019. We chose 1995 in acknowledgement of the seminal contribution of Zaheer (1995) in defining LOF. We conducted a comprehensive search of articles published in nine leading management journals and five top scholarly IB journals: Academy of Management Journal, Academy of Management Review, Administrative Science Quarterly, Management Science, Organization Science, Strategic Management Journal, Journal of International Business Studies, Journal of Management, Journal of Management Studies, Global Strategy Journal, Journal of World Business, International Business Review, Management International Review, and Journal of International Management. These 14 journals have frequently been included in previous reviews of IB research (e.g., Luo et al., 2019). We searched them using a series of keywords including foreignness, liability/liabilities, liability of foreignness, assets of foreignness, foreign companies, multinational, and multinational enterprise/multinational corporation (MNE/MNC). We used the keywords and their combinations to search article titles, abstracts, and keywords in the ABI/Inform, EBSCO Premier Business, and Web of Science databases. We then used a snowballing approach in which we successively tracked relevant articles cited in the retrieved papers on a rolling basis. Following this procedure, we identified 155 articles. The “Appendix” provides a full list of selected papers.

The majority of the articles (78%) were published in IB-oriented journals, with Journal of International Business Studies having the most (32), followed by Journal of International Management (30), including ten articles in the LOF special issue, and then by Journal of World Business (20). While fewer articles on the topic have appeared in general management-oriented journals, Strategic Management Journal has published a good number (19). From 1995 to 2019, the number of articles published on foreignness increased significantly, with two-thirds (106/155) appearing in the most recent decade.

Review Structure

We organize our review around four major foreignness research streams: LOF, AOF, drivers of foreignness, and firm responses to foreignness. To some extent, our classification of foreignness research reflects the chronological evolution of the literature. It also allows us to pinpoint differences between research streams and the extent of their integration.

We first review the literature on LOF, which was the focus of early research on foreignness (Hymer, 1976; Hennart, 1982; Zaheer, 1995) and which continues to dominate the field (Zaheer & Mosakowski, 1997; Luo & Mezias, 2002; Johanson & Vahlne, 2009; Denk et al., 2012; Wu & Salomon, 2017; Newenham-Kahindi & Stevens, 2018; Chen et al., 2019). Later, attention was paid to the advantages of foreignness (Brannen, 2004; Insch & Miller, 2005; Sethi & Judge, 2009; Nachum, 2010; Mallon & Fainshmidt, 2017; Taussig, 2017; Siegel et al., 2019), countering and complementing that on LOF. AOF is the second stream of research reviewed in this paper.

While Zaheer (1995) treats LOF as something which affects an MNE subsidiary in a particular host country, other researchers focus on the impact of the country of origin of its MNE parent (Elango & Sethi, 2007; Ramachandran & Pant, 2010), on the host-country factors that favor or disfavor an MNE (Arikan & Shenker, 2013; Sharma, 2015), on the institutional distance between an MNE’s home and host countries (Eden & Miller, 2004; Zhou & Guillén, 2015), and on MNE firm-specific advantages (Dunning, 1980, 2000). These streams of research are closely linked to research on LOF and AOF, but the connection needs to be more clearly identified. Take institutional distance for example, some studies treat it as a driver of LOF (Eden & Miller, 2004; Insch & Miller, 2005), others as a moderator of the impact of LOF (Añón Higón & Manjón Antolín, 2012), and still others as a control variable used when studying the impact of foreignness (Lindorfer et al., 2016; Tupper et al., 2018). As with the rise of research on LOF, a growing number of strategies have been identified to offset, mitigate, overcome and reshape foreignness. The inter-connectedness among these strategies and their connection with the core foreignness research are yet to be clarified.

To ensure the clarity and parsimony of the review, we categorize these different research streams by their relation to foreignness construct: drivers of foreignness vs. responses to foreignness. The third area of foreignness research reviewed here focuses on the drivers of foreignness, including country of origin, host-country factors, and institutional distance. The fourth one focuses on how firms manage foreignness, including the use of firm-specific advantages to offset LOF, imitation and innovation strategies to overcome it, organizational learning to mitigate it and identity management to strategically shape it.

Figure 1 highlights the core ideas behind the research streams, the relationships between those streams, the remaining issues and debates, and avenues for future research. The balloon in the center features the core concepts of LOF and AOF which we see as two sides of the foreignness coin. We use Yin and Yang to illustrate their interconnectedness. The left-hand box lists the research streams centered on the drivers of foreignness. They are mainly at the country level and include country of origin, host-country factors, and home–host-country distance. The arrow pointing to the right illustrates that these factors may influence, moderate, or qualify foreignness. The right-hand box summarizes the literature on firm responses to foreignness, with an arrow pointing to the left to indicate how they can offset, overcome, and manage foreignness.

RESEARCH ON LIABILITIES OF FOREIGNNESS

From Costs of Doing Business Abroad to LOF

It is well documented in the IB literature that doing business abroad incurs additional costs (Hymer, 1976; Dunning, 1977; Hennart, 1982). Hymer (1976) takes a rather broad perspective on this identifying two major types of costs. First, there are the additional costs MNEs incur when operating abroad compared to operating in their home country (Buckley & Casson, 1998). Second, MNEs have costs to which indigenous firms in a host country are not subject.

Zaheer (1995; 342–343) introduced the term LOF and defined it as “the costs of doing business abroad that result in a competitive disadvantage for an MNE subunit ...broadly defined as all additional costs a firm operating in a market overseas incurs that a local firm would not incur”. While the original conceptualization of the costs of doing business abroad covers both the economic (spatial and market) factors and social pressures, LOF tends to place more emphasis on the impacts of sociopolitical factors (Zaheer, 2002; Eden & Miller, 2004) or what Zaheer (2002) would label as structural/relational or institutional factors that affect MNEs’ access to and acceptance in a host country. She specifically identifies four sets of costs: those associated with spatial distance such as travel and transportation, those related to host-country unfamiliarity and lack of embeddedness, those arising from discrimination by host-country actors (e.g., economic nationalism), and those due to constraints imposed by home-country policies (e.g., restrictions on high-technology sales to certain countries imposed on US-owned MNEs).

Eden and Miller (2004) break LOF down into three categories: unfamiliarity, discrimination, and relational hazards, which clearly align with the social, political, and institutional aspects of LOF. A lack of legitimacy, coupled with information asymmetry and economic nationalism in host countries, gives rise to a lack of trust in foreign firms and sometimes discrimination against them (Baik et al., 2013; Elango, 2009; Kim, 2019; Kim & Jensen, 2014; Krug & Hegarty, 2001; Li, 2008; Li, Poppo, & Zhou, 2008; Obadia, 2013; Wu & Salomon, 2017).

Theoretical Grounding of LOF

Which theories have been used to explain LOF? Of the papers reviewed, 11% do not have a clear theoretical underpinning while 13% use more than one. Among the papers with at least one clear theoretical perspective, institutional theory is the most frequently used at 60%, followed by the resource-based view 17%, MNE/transaction cost theories 17%, and social network theories 5%. Since 2010 (the end of review period of Denk et al., 2012) there has been increased emphasis on institutional and social network theories and a decline in the use of resource-based view and MNE/transaction cost theories.

Institutional theory suggests that institutional norms vary from one country to another and are often tacit in nature, making it difficult for foreign subsidiaries to identify, understand, and implement them (Peng et al., 2008; García-García et al., 2019). The institutional differences between home and host countries usually results in an LOF (Zaheer, 1995; Petersen & Pedersen, 2002; Eden & Miller, 2004).

Following DiMaggio and Powell (1983), researchers have implicitly or explicitly seen interorganizational mimetic behavior as a way to overcome LOF (Bell et al., 2012; Salomon & Wu, 2012; Wu & Salomon, 2016). A strong assumption underlying this approach is that a larger distance between host and home-country institutions results in a greater LOF, and hence lower legitimacy and poorer performance (Bae & Salomon, 2010; Kostova et al., 2019). Some researchers have questioned this assumption (Shenkar et al., 2008; Luo & Shenkar, 2011) and taken a more agentic approach while still using an institutional lens (Regnér & Edman, 2014; Edman, 2016a; Newenham-Kahindi & Stevens, 2018). This line of research emphasizes that institutions are not static and should not be taken for granted. Instead, MNEs could take a proactive role and shape institutions (Phillips et al., 2009; Cantwell et al., 2010; Caussat et al., 2019). It has been documented that MNEs can escape from the pressure to conform to (Kostova & Roth, 2002; Luo et al., 2002), or even deviate from institutional norms (Regnér & Edman, 2014; Fortwengel & Jackson, 2016). Thus, MNE subsidiaries do not always need to conform to be considered legitimate (Edman, 2016a, 2016b).

According to MNE/transaction cost theories, firms decide to expand abroad based on a systematic analysis of the costs and benefits associated with internationalization (Hymer, 1976; Dunning, 1980; Hennart, 1982); and that the costs, or LOF, will increase with cultural, economic, and geographic distance (Asmussen, 2009; Johanson & Vahlne, 2009). The resource-based view suggests that LOF arises from the difficulty of transferring ownership advantages/resources to host countries or from the lack of complementary resources there (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2007). Beyond economic calculations, sociological perspectives stress social and relational context as a driver of LOF. The social capital/network perspective emphasizes the lack of embeddedness of foreign subsidiaries in local networks (Mezias, 2002a, 2002b; Johanson & Vahlne, 2009; Kim, 2019) and the need to develop ties with host-country stakeholders to alleviate the relational hazards of LOF (Rangan & Drummond, 2004; Li et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2018; Valentino et al., 2018).

Impact of LOF

Since Zaheer’s (1995) original empirical study, other ones have found that LOF is likely to have a negative impact on MNE performance. There is evidence that foreign firms perform poorly compared to indigenous rivals in host countries (Zaheer, 1995; Buchner et al., 2018). For example, foreign banks have lower X-efficiency compared to their host-country counterparts in the global banking industry (Miller & Parkhe, 2002), and are deterred from entering the US by domestic banks (Li, 2008); also, some foreign firms exit host countries due to LOF (Hennart et al., 2002; Mata & Freitas, 2012), face more US labor-related lawsuits than US firms (Mezias, 2002b), have less access to financial markets (Bell et al., 2012; Gu et al., 2019), are less likely to be able to influence US decision makers (Kim, 2019), and finally, have exit rates higher than those of their local rivals (Zaheer & Mosakowski, 1997; Mata & Alves, 2018).

However, the results of many studies appear mixed, with a number of findings contradictory to the predictions of LOF theories (Nachum, 2003; Kronborg & Thomsen, 2009; Denk et al., 2012). For instance, Mata and Portugal (2002) observe that, among new Portuguese firms, there is little difference between foreign and domestic firms in survival rates and exit patterns. Nachum (2003) reports that foreign banks in London do not suffer from LOF, and in fact are more profitable, grow faster, and survive longer than local banks. Kronborg and Thomsen (2009) find that foreign firms in Denmark actually enjoy a survival premium over local firms, at least when the density of foreign firms is low in that country. Taken together, these results point to the importance of clarifying the theoretical mechanisms through which foreignness works and of considering the potential advantages of foreignness as well as other contextual factors that qualify and moderate its effects (Luo & Mezias, 2002; Mezias, 2002a; Sethi & Judge, 2009; Edman, 2016a).

As the “Overcoming the liability of foreignness” title of Zaheer’s (1995) article indicates, while foreignness is considered a burden, hindrance, or disadvantage, MNEs can sometimes offset, reduce, or overcome it (Eden & Miller, 2004; Elango, 2009; Kim & Jensen, 2014; Wu & Salomon, 2016, 2017). As such, the extent to which an MNE is aware of its LOF, motivated to respond, and capable of overcoming it, will affect the relationship between LOF and MNE performance.

Summary of LOF Research

Our review shows a literature with interesting yet inconsistent findings. We believe that this has to do with the very definition of foreignness. Is foreignness a yes-no binary variable, or are there different degrees, brands, or manifestations of it? Is foreignness a country-pair level phenomenon (Zaheer, 1995; Mezias, 2002a; Eden & Miller, 2004) or a firm-level variable (Edman, 2016a; Pant & Ramachandran, 2017)? Previous research has tended to feature a rather broad and somewhat varied definition of LOF (e.g., Sethi & Judge, 2009), which is often undifferentiated from similar terms commonly used in the literature (Mallon & Fainshmidt, 2017).

In addition to lacking a precise definition, the LOF construct is often poorly specified and operationalized. Although many studies use the concept of foreignness in the development of a theoretical framework, not all of them measure it directly. Many of those which do use a foreign/local dichotomy, that is, whether firms or individuals operate in a foreign or a domestic country. There are significant differences in the way foreignness as a continuous variable has been measured, ranging from the distance between home and host countries (geographic, political, economic, cultural, and regulatory), to the density of foreign firms or the amount of foreign direct investment (FDI) in a host country. Moreover, probably due to data limitations, many studies simply use poor or declining MNE performance as an indication of LOF, which is potentially tautological. Such inconsistency in measurement could be another reason for the mixed findings obtained in empirical tests of LOF.

Besides measurement, there is considerable variation across studies in terms of data sources, time spans, empirical settings, and methodologies used. Although arguably this enhances the richness and complexity of empirical tests, it also means that a definitive picture continues to elude us. For example, foreignness is often taken to be invariant in time, but as MNEs gain experience in a host country, their LOF may decrease or indeed eventually disappear (Zaheer, 1995; Zaheer & Mosakowski, 1997; Delios & Beamish, 2001; Lu & Beamish, 2001, 2004; Gaur & Lu, 2007). Differences across studies in the age and stage of foreign subsidiaries sampled may also explain, at least in part, the mixed findings on the impact of LOF.

RESEARCH ON ASSETS OF FOREIGNNESS

Although the literature on foreignness has often emphasized liability, an increasing body of work demonstrates the existence and impact of positive aspects. This research stream argues that, in addition to or despite the effects of LOF, foreignness may grant specific advantages to foreign firms relative to local rivals or it may allow them to offset the negative impact of LOF (e.g., Nachum, 2003; Brannen, 2004; Kronborg & Thomsen, 2009; Sethi & Judge, 2009; Mallon & Fainshmidt, 2017). Thus, foreignness may be an asset. While the asset of foreignness concept can be traced back to Kindleberger’s (1969) observation that foreignness can confer advantages to MNEs by enabling them to access favorable treatment unavailable to local firms (Mezias, 2002a), the debates on legitimacy have contributed to the growth in the AOF research (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999). More recently, Sethi and Judge (2009) formally advance the AOF concept, and Mallon and Fainshmidt (2017) discuss its theoretical underpinnings.

Legitimacy as a Benefit of Foreignness

Although Zaheer (1995) begins by emphasizing the liability aspects of foreignness, she also alludes to the potential for AOF (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999). She argues that one of the key aspects of foreignness is legitimacy. Indeed, lack of legitimacy is often cited as an attribute of LOF or as evidence of its presence. However, foreign firms may actually possess more legitimacy than local companies, some of which may not be trusted by locals. Subsequent work by Kostova and Roth (2002) contend that MNEs may not need to conform to local institutions or be isomorphic with local firms because their foreignness can act as a buffer, particularly when they are powerful and thus less dependent on host countries.

Building on this reasoning, Insch and Miller (2005) expand on the concept of “benefit of foreignness” and empirically examine favorable or unfavorable perceptions of foreignness in different host countries. They report that industrial buyers in the US and Mexico have different perceptions of it; it is a liability in the US but a benefit in Mexico. There is also evidence that consumers in less-developed countries tend to view companies from more developed countries more favorably than they do their local firms (Yildiz & Fey, 2012). Similarly, in host countries where there is extensive corruption, foreignness can have a positive effect. Firms originating from countries that are perceived to be less corrupt may be more trusted by local partners than local firms, and this can give foreign firms a competitive advantage (Calhoun, 2002).

AOF as a Benefit of Doing Business Abroad

On the conceptual front, Sethi and Judge (2009) provide one of the earliest formal accounts of AOF. Using the overarching terms costs of doing business abroad and benefits of doing business abroad, they systematically compare and contrast the components of LOF and AOF. However, they do not differentiate clearly between foreignness and firm-specific advantages, as their AOF list includes incentives from host countries, brand image and superior proprietary technology, first-mover advantages, and ability to influence the national legislation and policy of the host country. While the first item on the list, which would include preferential treatment by a host-country government eager to bring in foreign capital, or upgrade technology, or generate employment opportunities (Sethi & Judge, 2009; Yildiz & Fey, 2012; Anderson & Sutherland, 2015), is unequivocally an advantage that can be attributed to foreignness, most of the other items are firm-specific attributes that do not necessarily relate to foreignness per se but are nonetheless benefits of doing business abroad.

In one of the earliest accounts of AOF, Brannen (2004) shows that whether foreignness is a liability or an asset depends on the host-country context and how an MNE portrays itself. She shows that Disney’s particular foreign image was a liability in France when developing a theme park, but an asset in Japan where the brand, in fact American culture in general, is more favorably received.

As Sethi and Judge (2009) suggest, first-mover advantage can also be an AOF for MNEs. In a study of the health care industry in South Africa, Wöcke and Moodley (2015) document that foreign firms were typically the first movers, operating for almost twice as long as local firms. Foreign firms often help set the industry standard and thereby influence host-country government policies, giving them an advantage over local firms.

Kronborg and Thomsen (2009) show that foreign firms in Denmark enjoy a survival premium, although it does decline over time and disappears entirely when the entry of more foreign firms intensifies competition. Foreign firms are also found to be more resilient than their local competitors during economic recessions (Varum & Rocha, 2011). Likewise, foreign entrepreneurs may enjoy advantages by leveraging their home-country connections, which helps them build relationships and gain legitimacy in host countries (Kulchina, 2017; Stoyanov et al., 2018).

Theoretical Grounding of AOF

Mallon and Fainshmidt (2017) start from the fundamental question of why AOF exists and attempt to consolidate the conceptual foundations of AOF using the three theoretical perspectives that dominate research in the field, institutional theory, the resource-based view, and transaction cost economics. In our review, institutional theory was used in 42% of the studies, followed by MNE/transaction cost theories in 31%, and the resource-based view in 23%.

With 97% of articles grounded in at least one theoretical perspective, AOF research has a somewhat clearer theoretical focus than LOF research. As AOF is a more recent theoretical development, that high percentage shows that foreignness research has advanced over time. AOF research also relies less on the institutional perspective and more on other theories as it focuses more on firms than on their external environments. Despite these differences, LOF and AOF research share the same major theoretical foundations, reflecting the intertwined nature of these two research streams.

Peng and colleagues (2008), taking a broadly interpreted institutional perspective, give the following examples of AOF: location advantages (Dunning, 1980), greater survival rate (Li & Guisinger, 1991; Kronborg & Thomsen, 2009), positive country-of-origin perceptions (Verlegh & Steenkamp, 1999), negative perceptions of local firms (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999), positive attitude toward foreign firms (Nachum, 2010; Newburry, Gardberg, & Belkin, et al., 2006), and technological advances in the home country of a foreign firm (Insch & Miller, 2005). According to the resource-based view, foreign firms derive competitive advantages from their access to unique resources unavailable to local firms (Nachum, 2003; Kronborg & Thomsen, 2009; Boehe, 2011; Demirbag et al., 2016) and from tangible and intangible ownership advantages originating in their home countries (Dunning, 1980). MNE/transaction cost theories stress internalization advantages enjoyed (Dunning, 1980) and subsidies and incentives received by MNEs (Sethi et al., 2002; Sethi & Judge, 2009).

Edman (2016a) attempts to consolidate the different theoretical foundations of LOF and of AOF by arguing that a firm’s foreignness is not just a country-level imprint but also a firm-level identity that can be purposefully managed. This identity-based framework represents the first attempt at explaining how LOF and AOF can be actively managed by MNEs.

Impact of AOF

As we wrote earlier, the impact of AOF is reflected in higher foreign firm legitimacy (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999; Insch & Miller, 2005), better brand image (Brannen, 2004), and greater survival rates (Kronborg & Thomsen, 2009). Recent studies show additional advantages to being foreign, including access to unique talent pools (Yildiz & Fey, 2012; Siegel et al., 2019), more adaptability to underdeveloped host-country institutional environments (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008), entrepreneurial learning advantages (Zhou et al., 2010), and more opportunities to leverage global reach and presence (Taussig, 2017). And product innovation, a relatively new dependent variable in the foreignness research (Un, 2011, 2016).

Un (2011) argues that an MNE subsidiary is likely to be more innovative than its local rivals because it has to compete vigorously with its peers operating in other host countries to receive subsidies from its parent for its innovative efforts. A second reason for greater innovativeness is that a foreign subsidiary often faces stronger pressure from host-country customers who tend to have higher expectations of foreign firms than local ones. Un (2016) further examines the competitive disadvantage of a domestic firm vis-à-vis the subsidiary of a foreign MNE. She argues that the employees of local firms are usually more monocultural, and this limits their ability to identify, transfer, and integrate the diverse body of knowledge necessary for innovation. This study, along with that of Jiang and Stening (2013), adds to the body of research that views the liability of localness (LOL), a term coined by Perez-Batres and Eden (2008), as an alternative way to look at AOF.

Summary of the AOF Research

While AOF research has deepened our understanding of foreignness by showing its positive side, it suffers from the same limitations as LOF research, namely the lack of a precise definition and measurement. Despite the comprehensive treatment offered by Sethi and Judge (2009) and Mallon and Fainshmidt (2017), how AOF arises is not clearly specified in empirical studies (Kronborg & Thomsen, 2009; Varum & Rocha, 2011). Further explanation is needed to differentiate similar but different concepts in future studies. For instance, does the fact that some firms derive advantages from their foreignness automatically means that local firms face a corresponding disadvantage because of their localness (Perez-Batres & Eden, 2008)?

Another key issue is the relationship between LOF and AOF. Are they always conceptualized and compared on the same dimensions? Could an LOF change into an AOF or vice versa? Are they mutually exclusive, or can they coexist? How do they jointly affect MNE performance in a host country? Integration of LOF and AOF research is needed to address these questions. It is important to consider the context, for instance the level of economic development of host and home countries (Pant & Ramachandran, 2012; Bhaumik et al., 2016), because an MNE’s foreignness can be an asset in one host country but a liability in another (e.g., Brannen, 2004). In other words, foreignness per se can be either a liability or asset, depending on the context.

AOF research has also broadened the scope of dependent variables used in foreignness research. In addition to the usual variables, such as financial performance or survival, AOF researchers have examined the effect that foreignness has on MNE innovation (e.g., Un, 2011). Future research could look at the impact of foreignness on other MNE decisions, such as location, speed, mode, and scale of foreign market entry and at how LOF and AOF jointly affect MNE host-country entries and exits over time.

RESEARCH ON DRIVERS OF FOREIGNNESS

In the studies on LOF and AOF, foreignness is not viewed by all scholars as a simple binary concept but is qualified by and imbued with contextual attributes of home and host countries/regions. Three research streams have looked at the country-level drivers of foreignness, country of origin (Peterson & Jolibert, 1995; Elango & Sethi, 2007), host-country factors (Regnér & Edman, 2014; Taussig, 2017), and institutional distance (Eden & Miller, 2004; Salomon & Wu, 2012; Zhou & Guillén, 2015; Kostova et al., 2019). Two of the three, country of origin and institutional distance, were initially separate research streams, but are now increasingly seen as different manifestations of foreignness.

Country of Origin and Foreignness

Country-of-origin effects have long been of interest to researchers in international marketing. Bilkey and Nes (1982) suggest that they act as a cue to host-country buyers who tend to link a stereotypical view of a country with the quality of the products it manufactures. Porter’s (1990) treatment of the competitive advantage of nations also emphasizes a home-country’s imprint on the image and competitiveness of its firms. Subsequent meta-analyses have confirmed the existence of a country-of-origin effect (Peterson & Jolibert, 1995) and its relationship to country competitiveness (Verlegh & Steenkamp, 1999).

In the IB literature, Sethi and Elango (1999) argue that a country’s physical and human resources, as well as its political and cultural institutions, can provide its firms with competitive advantages. Specifically, they cite three components of country of origin: national government’s economic and industrial policies, economic and physical resources and industrial capabilities, and cultural values and institutional norms.

Ramachandran and Pant (2010) suggest that an MNE’s identity is shaped by home-country imprinting, which could lead to disadvantages in doing business abroad. This has been called the liability of origin. A liability of this kind can stem from the macro context, such as a country’s economic and institutional infrastructure, or from the micro context, a firm’s structures, rules, and routines, which are assumed to reflect home-country culture. Moeller et al. (2013) systematically uncover a host of country-of-origin factors that hinder the acceptance of foreign firms by host-country stakeholders and then encourage foreign firms to develop proactive strategies to address “negativism” in their host countries.

It is important to recognize that the country-of-origin effect can be positive and thus contribute to an MNE’s AOF. Eden and Miller (2004) argue that foreignness can be an advantage, depending on the country of origin. French wines, Swiss watches, Cuban cigars, and Hollywood films do not enjoy brand premiums because of their foreignness per se, but because they originate in countries where those products are known for uniqueness and quality. As such, it is not foreignness per se in general, but foreignness related to certain home countries, which constitutes AOF originating from those home countries (cf. Mata & Portugal, 2002; Moeller et al., 2013).

It should be noted that the country-of-origin effect could be either homogeneous at the country level (Bilkey & Nes, 1982; Verlegh & Steenkamp, 1999) or varying by product categories (Josiassen et al., 2013; Andéhn et al., 2016). On the one hand, country-of-origin effects, whether positive or negative, can apply to many, or even all, of the products and firms from a given country. A country that is itself less competitive and more xenophobic might take for granted that all of the firms based in a more prestigious foreign country will produce better products than any local firms can. On the other hand, the country-of-origin effect may only apply to certain product categories. After all, just because people tend to favor Cuban cigars does not mean that they also prefer Cuban caviar.

On the topic of a home-country’s role in doing business abroad, the policies and regulations of the home country of MNEs could present incentives or hindrances for their internationalization, even if not necessarily related to foreignness per se. For instance, they may prefer doing business abroad if exports are encouraged by tax exemptions or other policies (Sethi & Elango, 1999; Luo et al., 2010). Moreover, the presence of institutional voids, such as home-country corruption and bureaucracy, may create incentives for emerging economy MNEs to internationalize (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008; Stoian & Mohr, 2016). On the other hand, home-country governments do sometimes impose restrictions on the internationalization of firms in certain industries (Sofka & Zimmermann, 2008).

Country-of-origin research has several implications for foreignness research. First, country of origin is not only an important source of LOF and AOF but it is also a fresh perspective through which to understand foreignness as it focuses on customer perceptions. Second, the country-of-origin literature does not necessarily look on foreignness as a liability, but also sees its possibility as a premium, depending on the relative positions of two countries and specific characteristics of products. Finally, country-of-origin research suggests that firms can strategically manage foreignness. As the globalization of value chain tends to hide the country of origin, a firm can manage foreignness by playing on terms such as “made in” and “assembled in” to selectively highlight a prestigious location in the value chain. For instance, to project a Californian image, Apple downplays the fact that its iPhone is assembled in China.

Host-Country Factors and Foreignness

As the foreignness of MNEs is defined and interpreted by actors in a particular host country, it is logical to take into consideration the characteristics of that country. One of the earliest treatments of a host country’s role can be found in the OLI framework, one of the dominant paradigms in IB (Dunning, 1980, 2000). The OLI paradigm suggests that MNEs derive advantages from international activities through the configuration of ownership-specific advantages (O), location-bound endowments (L), and internalization advantages (I). The location factor is especially relevant to the study of foreignness as it focuses on the particular endowments of a host country, its factor and product markets, and its policies and regulations. The extent to which MNEs can access these host-country-specific advantages depends, however, on their transactional characteristics (Rugman & Verbeke, 1992; Hennart, 2009).

Xenophilia and xenophobia have important ramifications for how the foreignness of MNEs is perceived in a host country (Arikan & Shenkar, 2013; Sharma, 2015; Edman, 2016a). To mitigate the negative impact of LOF, MNEs often choose to enter xenophilic host countries where highly trained employees are more willing to work for foreign than for local firms and where they can access land and other inputs on preferential terms. In xenophobic host countries, a hostile or conservative attitude toward foreignness can increase the level of LOF. In response to social pressure or government policies, consumers may shun foreign products (Shimp & Sharma, 1987; Balabanis & Diamantopoulos, 2004; Sharma, 2015).

It is also interesting to note that the impact of foreignness can be neutral or irrelevant under certain host-country conditions. For instance, in countries with many foreign firms, foreignness is no longer an alien phenomenon or a substantive source of either liability or asset (Nachum, 2003; Goerzen et al., 2013).

Institutional Distance and Foreignness

The distance between an MNE’s home and host countries often qualifies the nature and degree of foreignness. Distance is a multidimensional construct which includes geographic (e.g., Buchner et al., 2018), psychic (e.g., Johanson & Vahlne, 1977; O’Grady & Lane, 1996; Evans & Mavondo, 2002; Ellis, 2008), cultural (e.g., Kogut & Singh, 1988; Morosini et al., 1998; Brouthers & Brouthers, 2001; Shenkar, 2001; Tihanyi et al., 2005), and institutional distance (e.g., Xu & Shenkar, 2002; Eden & Miller, 2004; Berry et al., 2010; Gu & Lu, 2011). Ghemawat (2001) further proposes a CAGE model that incorporates cultural, administrative, geographic, and economic factors.

The type of distance most widely covered in the literature – and most relevant to research on foreignness – is institutional distance (Kostova et al., 2019). Its relationship to foreignness is multifaceted and complicated. Defined as the degree of similarity between the institutional environments of two countries (Gaur & Lu, 2007), institutional distance is believed to be at the root of LOF (Bae & Salomon, 2010) and its key driver (Eden & Miller, 2004). Bell et al. (2012) argue that institutional distance, information costs, unfamiliarity with the local environment, and cultural distance are the four main sources of LOF. Research also suggests that institutional distance reduces the willingness and ability of firms to implement certain LOF-reducing strategies, such as engaging in CSR activities (Campbell et al., 2012). Institutional distance also interacts with firm factors. Añón Higón and Manjón Antolín (2012) show that it accentuates the negative impact of foreignness on R&D productivity.

Institutional distance can be measured along formal and informal dimensions, with the formal ones including regulatory, political, and economic institutions and the informal ones social, cultural, and cognitive aspects (Bae & Salomon, 2010). These dimensions are usually correlated, and their impact on specific firm outcomes often not uniform (Bae & Salomon, 2010; Buchner et al., 2018). Most studies tend to focus on just one or two specific dimensions, and their measurement has been inconsistent, leading to mixed findings (Bae & Salomon, 2010).

Most studies of institutional distance use objective measures and overlook the role played by managers (Zaheer et al., 2012; Maseland et al., 2018) who make decisions on the basis of subjective rather than objective distance (Azar & Drogendijk, 2019). Evans and Mavondo (2002) and O’Grady and Lane (1996) have pointed to a paradox related to distance: managers tend to underestimate distance to familiar countries. Recent research points to a nonlinear impact of distance when taking into account both firms’ anticipation of and adaptation to institutional distance (Dinner et al., 2019).

MNEs often make sequential entries, expanding into new markets after accumulating experience in other host countries. Such a pattern makes home-country-based distance measures less accurate (Nachum & Song, 2011; Zaheer et al., 2012). Furthermore, some recent literature suggests considering distance at a subnational (Sofka & Zimmermann, 2008; Maggioni et al., 2019) or regional level (Asmussen & Goerzen, 2013; Pla‐Barber, Villar, & Madhok, 2018; Qian et al., 2013) rather than at a country level, since institutions may differ within a country (Arregle et al., 2016).

Research on distance has several implications for foreignness research. The first is that distance is quantifiable. Hence, correlating foreignness with the distance between home and host countries enables us to measure it as a continuous variable. Second, while most studies use the absolute difference between countries as a measure of distance, positive and negative differences do not have the same ramifications (Shenkar, 2001; Zaheer et al., 2012). Given the same institutional distance, an MNE based in a country with a higher level of institutional development investing into one with a lower level of institutional development may find that foreignness is an asset, while it may be a liability for a firm based in a country with less developed institutions investing in one with more developed institutions. This means that foreignness can have both positive and negative effects. Perhaps it is the difference, rather than the distance, that really matters (Maseland et al., 2018: 1160).

Moreover, institutional distance may not be static since MNEs can shape institutions (Phillips et al., 2009). This line of research is echoed in recent work on foreignness that acknowledges the proactive role of firms (e.g., Caussat et al., 2019; Edelman, 2016a, 2016b; Regnér & Edman, 2014). Research in this area shows that MNEs can take advantage of variations in institutional strength, thickness, and resources to overcome institutional distance (Fortwengel, 2017), thus escaping from institutional constraints (Fortwengel & Jackson, 2016).

Researchers have also acknowledged that distance can generate positive effects by increasing team diversity (Stahl & Tung, 2015; Maseland et al., 2018). For instance, distance can raise awareness of the difference between host and home countries and therefore help firms adapt, resulting in improved performance (O’Grady & Lane, 1996; Evans & Mavondo, 2002). This suggests that distance may be a potential asset for synergy, innovation, and learning, and hence a source of AOF (Zaheer et al., 2012; Stahl et al., 2016).

Summary of Research on the Drivers of Foreignness

In this field of research, foreignness has largely been conceived as a country-pair-level construct. That is, LOF and AOF have been seen as arising from bilateral differences between home and host countries (Brannen, 2004; Moeller et al, 2013) in terms of the regions to which they belong, their economic development status, and their competence in a certain sector/industry/trade (Miller & Richards, 2002). As such, it is meaningful and indeed imperative to clearly specify contextual factors when conceptualizing and operationalizing foreignness. Specifically, whether foreignness is a liability or an asset may depend on an MNE’s country of origin regardless of its own (Eden & Miller, 2004). Some less developed countries might excel in certain industries due to unique historical inheritance. Again, it may not be that being foreign bestows an advantage, but instead coming from a home country with particular competencies in specific industries (Mata & Portugal, 2002; Moeller et al., 2013). Prior research (particularly on LOF or AOF) seems to have ignored the fact that it is a particular brand or type of foreignness that really matters.

The ways in which research on institutional distance (as antecedent to, embodiment of, or moderator of foreignness) could complement and enhance research on LOF and AOF remains underexplored. This is a missed opportunity as the concept of institutional distance not only provides a more specific measure of the degree of foreignness, but also enriches its conceptualization by incorporating its regulatory, political, economic, social, cultural, and cognitive dimensions. Moreover, the institutional distance research to date suggests that distance may not always be a disadvantage, as it can also provide opportunities for innovation. This line of research could be particularly beneficial in advancing AOF theory.

The above summary implies that introducing a greater country variety to the foreignness research could be very important, as this would afford a significant opportunity to examine how MNEs from different home countries learn and adapt to different host-country settings. Our review shows, however, that to date research has focused on a relatively small set of countries and regions (Oetzel & Doh, 2009), with 47% of the empirical articles focusing on European countries and 31% on the US. African countries have received minimal attention, although parts of the continent are increasingly attracting MNEs from both developed and developing countries (Newenham-Kahindi & Stevens, 2018). The lack of attention to developing countries leaves a space for the further conceptualization of foreignness.

RESEARCH ON RESPONSES TO FOREIGNNESS

Following the hints of Hymer (1976) and Zaheer (1995), the LOF research tends to look first at whether or how MNEs rely on their firm-specific advantages arising from unique resources and capabilities to compensate for or mitigate LOF (Zaheer & Mosakowski, 1997; Nachum, 2003; Rangan & Drummond, 2004). After all, firm-specific advantages are cited as the primary rationale for MNEs doing business abroad, given the existence and impact of LOF (Buckley & Casson, 1976; Caves 1971, 1996; Hymer, 1976; Zaheer, 1995). Firm-specific advantages might offset the negative impact of LOF on MNE subsidiary performance, but they do not directly reduce or minimize LOF per se. Over time, MNEs have adopted a variety of strategies to reduce LOF include learning – at MNE level and subsidiary level, imitation, innovation, and other market and non-market strategies. Recent research perceives foreignness as a firm identity and points to new strategies to manage it. Below we look at five such strategies: (1) use of firm-specific advantages to offset it, (2) imitation and (3) innovation to overcome it, and (4) organizational learning and (5) identity shifting to manage it.

Firm-specific Advantages

Firm-specific advantages are not directly related to a firm’s foreignness. They are, by definition, firm-level factors so neither are they necessarily related to the country of origin per se. We spell this out as firm-specific advantages can confound the effects of foreignness. Foreignness research in IB has taken firm-specific advantages to be the most effective defense against the negative impact of LOF on MNE performance (Zaheer, 1995; Rugman & Verbeke, 2001; Denk et al., 2012; Hillemann & Gestrin, 2016).

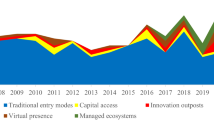

Long before the resource-based view came to prominence, the OLI Framework emphasized the importance of ownership advantages. Ownership-based, firm-specific advantages include human capital and organizational culture, patents and technical know-how, trademarks and brand images, marketing prowess, and organizational routines and competencies (Dunning, 1980, 2000; Singh & Kundu, 2002) that allow MNEs to remain viable despite the presence and impact of LOF in host countries (Zaheer, 1995; Nachum, 2003; Rangan & Drummond, 2004; Stoian & Mohr, 2016). In the information age, an MNE may have to tap into an even broader scope of factors to deal with its foreignness. Specifically, ownership advantages need to incorporate an MNE’s ability to acquire and recombine knowledge from diverse sources; location ones become increasingly clustered while remaining interconnected, and internationalization ones go beyond internal facilities and traditional arm’s length transactions to include network-based ecosystems (Alcácer et al., 2016).

Obviously, OLI refers to the whole MNE, while LOF and AOF look at MNE subsidiaries in given host countries. As the parent-subsidiary relationship is an important factor when examining how a subsidiary can reduce its LOF in a particular one, the OLI literature now considers subsidiary-specific advantages. Here, firm- and country-specific advantages combine to make the subsidiary a springboard that takes on the role of a regional headquarter (Pla-Barber et al., 2018; Villar et al., 2018).

Imitation

As the essence of foreignness is the unfamiliarity with a host country due to the dissimilarity between home and host countries (Kindleberger, 1969; Hymer, 1976; Brannen, 2004), an obvious way of attempting to reduce LOF is to imitate indigenous firms in an effort to create an isomorphic fit with the host country (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999; Eden & Miller, 2004; Salomon & Wu, 2012; Wu & Salomon, 2016). A number of tools are identified in the literature, such as local networking, input localization, and legitimacy improvement (Luo et al., 2002); bonding, signaling, organizational isomorphism, and reputational endorsements (Bell et al., 2012); and reassurance, measurement, co-option, collective action, and validation (Pant & Ramachandran, 2012).

Becoming embedded locally and gaining acceptance within the local business network are extremely challenging. An MNE might work towards legitimization by recruiting locally (Mezias, 2002b; Goodall & Roberts, 2003); by finding a way to tap into host-country entrepreneurial and managerial networks (Li et al., 2016; Kulchina, 2017; Guo et al., 2018; Mata & Alves, 2018; Valentino et al., 2018); by leveraging pre-existing geographic, colonial, linguistic, or institutional ties between the home and host country (Rangan & Drummond, 2004); or by taking on local investors (Chittoor et al., 2015; Jiménez et al., 2017).

Does imitation reduce LOF? Just as LOF is dynamic and may diminish over time (Zaheer & Mosakowski, 1997), so too may the imitation strategy intended to mitigate it wane. Wu and Salomon (2016) found that foreign banks operating in the US initially benefit from an imitation strategy, but that the effect diminishes over time. Moreover, isomorphism is not always feasible – or even desirable (Orr & Scott, 2008). It can be inconsistent with MNE home-country activities and jeopardize global economies of scale (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999), indeed it might reduce an MNE’s uniqueness, possibly the very reason why it is attractive to the host country in the first place (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008; Cantwell, et al., 2010).

Innovation

Innovation in business practices has often been seen as a way to overcome LOF. Firms can innovate in three areas: the product market, the factor market, and the non-market arena. Elango (2009) found that to be accepted in a host country, foreign firms need to be creative and to differentiate themselves from local firms. This may account for foreign firms in the US tending to have greater product variety and to sell in more states than US firms themselves do (cf. Garg & Delios, 2007). Foreign firms may engage in other product market adaptation practices as well, such as focusing on niche markets or reconfiguring product portfolios (Khan & Lew, 2018).

MNEs may also strategically manage their access to factor markets to overcome LOF. One possibility is to reduce dependence on local resources (Yildiz & Fey, 2012). Factor market strategies can be a valuable way to overcome LOF in capital markets (Lindorfer et al., 2016). Foreign firms may co-locate with other foreign firms to benefit from agglomerative economies and knowledge spillovers (Lamin & Livanis, 2013). Other factor market strategies include early entry and preemptive access to market resources (Hsu et al., 2017) and proactive rhetoric strategies (Caussat et al., 2019).

In addition to this research on innovative market strategies, there is a proliferation of studies on overcoming LOF through non-market strategies such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Campbell et al., 2012; Maruyama & Wu, 2015; Crilly et al., 2016; Del Bosco & Misani, 2016; Mithani, 2017) and corporate political strategy (Sojli & Tham, 2017; Wu & Salomon, 2017; Bucheli & Salvaj, 2018; Kim, 2019; Kline & Brown, 2019). Crilly et al. (2016) write that foreign firms can minimize LOF by engaging in “do-good” CSR activities, i.e., activities that generate positive externalities, but that merely engaging in “do-no-harm” CSR activities, i.e., activities that just seek to attenuate negative externalities, is often taken locally as a sign that a firm is not genuinely motivated to reduce the negative impact of its business activities, which may well increase LOF. Campbell and colleagues (2012), using a sample of foreign banks in the US, found that the higher the CAGE distance (Ghemawat, 2001) between the US and the home country of the bank, the lower the CSR engagement. MNEs can also reduce LOF through philanthropy. In a study that looks at philanthropic contributions following a natural disaster in India, Mithani (2017) shows that MNEs contributed more to relief than domestic firms did, and it appears that the impact on performance was stronger for MNEs than for domestic firms. In one way or another, all of these studies highlight the strategic role played by CSR in mitigating LOF.

Corporate political strategy can also reduce LOF. Kline and Brown (2019) find that foreign franchisors have a greater propensity to lobby the US government – and do it more intensely – than their US counterparts, and Kim (2019) that foreign firms obtained more US Department of Defense contracts if they hired local professional lobbyists who are trustworthy political insiders. Sojli and Tham (2017) show that having politicians and other politically connected individuals as shareholders improves access to a host-country's markets. Bucheli and Salvaj (2018) issue a warning: overt connections with highly visible local elites may backfire, becoming a liability in the event of major political changes.

An approach of straddling imitation and innovation has been used to lessen LOF through the co-creation of institutional logic by MNEs and their local employees who act as key intermediaries between the competing logics of MNEs and host countries. The study of MNEs in sub-Saharan Africa conducted by Newenham-Kahindi and Stevens (2018) demonstrates that such practices have different degrees of success depending on their implementation. Siegel et al. (2019) document that foreign MNEs in Korea have improved productivity and profitability when they aggressively hire women as managers. Firms following that strategy can benefit from a largely untapped talent pool in countries where women are largely excluded from managerial positions, thus providing them with a competitive advantage, increasing both legitimacy and profit.

Host-Country Experience and Learning

Shortly after the introduction of LOF to the literature, Zaheer and Mosakowski (1997) identify the dynamic nature of LOF in that, the extent of LOF faced by foreign firms in the banking industry diminishes over the 20-year span they studied. They argue that this is because foreign firms become more skilled at dealing with the negative consequences of foreignness, presumably through learning (Delios & Beamish, 2001; Henisz & Delios, 2001; Petersen & Pedersen, 2002; Gaur & Lu, 2007) and adaptation (Kostova & Roth, 2002; Campbell et al., 2012).

It is clear that learning is an essential element in the adaptation process (Petersen & Pedersen, 2002). CEOs and top management teams with members who have international education and foreign professional experience have a higher degree of tolerance for foreignness (Chittoor et al., 2015; Pisani et al., 2018; Rickley, 2019). Perhaps more importantly, as MNEs accumulate market knowledge about local customers, suppliers, and institutions, they become more familiar with host-country intricacies and feel more at ease (Zaheer & Mosakowski, 1997; Mezias, 2002b; Miller & Eden, 2006; Barnard, 2010; Wu & Salomon, 2016). Thus, LOF can be reduced as MNEs accumulate experience in foreign countries (Mezias et al., 2002) and build networks in them (Bucheli & Salvaj, 2018). A disadvantage can even become an advantage with the accumulation of international experience (Demirbag et al., 2016).

Moreover, MNE subsidiaries can leverage not only host-country experience but also experience gained from other countries (Regnér & Edman, 2014; Rickley & Karim, 2018). Wu and Salomon (2017) find that MNEs with third-country experience face fewer regulatory sanctions in a host country, while Perkins (2014) shows that prior regulatory experience in similar environments can significantly enhance their survival in host countries. Kim et al. (2012) further demonstrate that a subsidiary’s experience may benefit not only itself, but sibling subsidiaries and the MNE as a whole.

Foreignness as Firm Identity

One of the most recent advances in foreignness research is the identity-based framework (Edman, 2016a, 2016b). Essentially foreignness is seen as an organizational identity that can be managed. An MNE subsidiary is not a “specimen” that embodies or exemplifies its home country, thus conceptualizing foreignness as a country phenomenon is an oversimplification (cf. Zaheer, 2002). Edman (2016a: 675) sees “foreignness as an organizational identity, characterized by distinct internal and external attributes” and contends that MNE subsidiaries can manage their degree of foreignness, that is, their dissimilarity to local firms (Brannen, 2004). For Edman (2016a), foreign identities have attributes that are cognitive (foreign assumptions, mindsets, and interpretive frames) and structural (foreign languages, managerial cultures, formal systems, and programs), as well as external network positions (embeddedness and number of relationships), and an image (alien and outsider status). By attenuating or accentuating those, MNE subsidiaries can affect how country-level contextual factors create advantages or liabilities. Properly managed, foreignness may facilitate innovation, increase access to unique human capital, open new market segments, capture host-country consumer preferences, and unlock governmental support. By treating foreignness as a firm-level variable with different dimensions, the identity-based framework not only brings attention back to the foreignness construct, but also has the potential to offer a single consistent explanation for both LOF and AOF.

In advancing the identity-based framework, Edman (2016a) proposes that MNE subsidiaries often assume “minority identities” as their logics are likely to deviate from the dominant logics of host countries. He argues that minority identities are not necessarily illegitimate; subsidiaries with such identities can subsist as divergent and legitimate actors. In an empirical study of the Japanese loan syndication business in the 1990s, Edman (2016b) demonstrates that MNE subsidiaries can cultivate a minority identity so as to create or sustain market niches that deviate from the dominant logic of the industry (Kostova & Roth, 2002; Luo et al., 2002). That is, minority identities are not always forced upon peripheral firms, such as MNE subsidiaries, but can instead be purposeful choices made by them. The broad implication of this line of reasoning is that MNE subsidiaries can simultaneously attend to both LOF and AOF and not be confined by the pressure to conform isomorphically. In a similar vein, Shi and Hoskisson (2012) argue that MNEs can create advantages from their foreignness and exploit the benefits of “creative institutional deviance” to foster innovation. Regnér and Edman (2014) find that foreignness can be mobilized to challenge prevailing institutions and help build new markets.

The most recent contribution to subsidiary identity management comes from Pant and Ramachandran (2017). Following up on their earlier account of foreignness as an organizational identity in the context of emerging-economy MNEs (Ramachandran & Pant, 2010; Pant & Ramachandran, 2012), they examine how Hindustan Unilever (an Indian subsidiary of the Anglo-Dutch MNE Unilever) manages the paradox of identity duality in India. They contend that such firms need to balance the contradictory and interdependent characteristics of the “global” and “local” identities to simultaneously satisfy the institutional demands of the parent firm and of the host country. They show that subsidiary managers sustain a dynamic balance by resorting to two modes of identity management, logic ordering (privileging one identity over the other) and logic bridging (attempting integration).

Summary of Research on the Responses to Foreignness

Several issues emerge when examining firm responses to foreignness. Foreignness should be distinguished from firm-level traits, i.e., firm-specific advantages, although it has often been said that such advantages are the primary weapon available to MNEs attempting to offset LOF (Buckley & Casson, 1976; Caves, 1971; Hymer, 1976; Zaheer, 1995). However great such advantages may be, this does not mean that they automatically qualify as AOF, but are rather used by MNEs to better respond to LOF. Foreignness is also different from other sources of advantage accessible to MNEs operating in a given host country. For instance, there might be specific location-based advantages associated with operating in certain host countries (Dunning, 1980). However, such advantages or benefits (e.g., low-cost labor or materials) are compared primarily to those available to MNEs in their home countries or elsewhere, rather than to those available to their indigenous rivals. Overall, in order to tease out the firm-specific effect of MNEs, researchers need to clearly differentiate firm-specific advantages from those arising from LOF and AOF (cf. Sethi & Judge, 2009).

Furthermore, firm-specific advantages can only offset LOF if they are internationally transferable. Not only might firm-specific advantages be difficult to transfer, they may even become disadvantages when transferred across borders (Cuervo-Cazurra, et al., 2007). It is therefore important to differentiate location- and non-location-bound firm-specific advantages when attempting to determine their effects on foreignness (Iurkov & Benito, 2018). A similar issue arises with experience. Misapplication of experience, that is attempting to apply experience unrelated to the focal host-country’s environment, would, in fact, increase the chance of failure (Perkins, 2014). This further attests to the importance of host-country-specific learning. Time plays an important role in experience The accumulation of relevant experience takes time, time to increase local embeddedness (Zaheer, 1995), to reduce information asymmetry, and to alleviate unfamiliarity hazards (Tupper et al., 2018). While the specific time signature of an MNE’s operation in a host-country needs to be considered, the relevance of experience should be distinguished from the simple passage of time that alleviates the unfamiliarity hazard.

Scholars have explored a variety of strategies to overcome LOF, ranging from imitation to innovation through market and non-market strategies. However, most studies tend to focus on a single strategy in tracking how MNEs mitigate LOF, such as firm-specific advantages, CSR, networking, and so on, leaving unanswered questions like whether innovation is more effective than imitation in mitigating LOF and when a firm should adopt innovative rather than imitative strategies. Only a few studies consider multiple strategies. One such study is conducted by Regnér and Edman (2014), who consider innovation, arbitrage, circumvention, and adaptation as four types of strategies foreign subsidiaries can use to deal with LOF. They argue that innovation strategies will be more effective when the local institutional environment is ambiguous and when a foreign subsidiary can transfer resources from diverse institutional settings. Such an approach would help enhance our understanding of the strategic choices made by MNEs to overcome LOF.

Finally, more attention paid to subsidiary-level characteristics may fill in the blanks (Caussat et al., 2019). Is foreignness a subjective perception or an objective reality? The organizational identity perspective implies that foreignness is in the eyes of the local stakeholders. As such, subsidiaries should strategically shape their foreignness so that LOF can be mitigated or even reshaped (Edman, 2016a).

AVENUES FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Building on our review of the four major streams of research under the overarching foreignness construct, we now discuss the potential synergy between them. In doing so, we hope to identify the themes and patterns that link these streams together to inform future research. We also try to pinpoint promising new trends and opportunities emerging in more recent years, which we believe are likely to influence further work on foreignness.

Conceptualization and Specification of Foreignness

Foreignness has often been treated in the literature as a binary concept and been measured using a foreign–local dichotomy. More recent studies have incorporated other factors to measure its impact, institutional distance for example. LOF or AOF typically arise from bilateral relationships between home and host countries and are further influenced by the specific regions in which they are located, and by differences between them in terms of levels of economic development and sectoral competencies (Miller & Richards, 2002; Brannen, 2004; Moeller et al., 2013). Therefore, we call for refinement of the conceptualization of foreignness as a multidimensional construct that can vary across contexts and time, that is, both the home country and the host country and their attendant multilevel factors should all be considered. Zhou and Guillén (2016) is a good example of this approach. They offer a multidimensional definition of LOF grounded firmly in one of IB’s dominant paradigms, OLI (Dunning, 1980). They aim to bridge the literature on LOF and cross-national distance. The liability of outsidership (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009; Lu et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019), liability of regional foreignness (Rugman & Verbeke, 2007; Asmussen, 2009), liability of origin (Ramachandran & Pant, 2010), and liability of home base (Zhou & Guillén, 2015) approaches are also commendable efforts to refine and extend the foreignness construct.

Future research could build on the attempts already made to articulate the degree and scope of foreignness and to specify its layers of components. We see a need for more exacting research on the impact of country-of-origin traits (Moeller et al., 2013), region-specific and sector-specific traits (Asmussen & Goerzen, 2013), and the advantages and disadvantages extended to specific foreign firms in a host county (Zhou & Guillén, 2015). Such an approach would avoid the pitfall of treating LOF and AOF as undifferentiated wholesale concepts and in doing so, we believe, lead to a better understanding of who is affected by foreignness – all foreign firms, foreign firms from certain regions or in certain industries, or foreign firms hailing from countries at a given level of economic development.

The new conceptualization of foreignness we envision would also capture its dynamic nature. LOF and AOF rise and fall with changes in perceptions and attitudes within a host country as time passes or more widely as critical global events change people’s perceptions of particular countries. Further, LOF may reduce as MNEs accumulate experience in local markets (Mezias et al., 2002; Lu & Beamish, 2004), become embedded in local networks (Bucheli & Salvaj, 2018; Lu et al., 2018), or add value to local investors (Bell et al., 2012; Tupper et al., 2018). Indeed, not only might LOF be reduced, but it might become an AOF. The last context we list above, benefiting local investors, is a case in point. A foreign firm may experience an LOF when first listing in a foreign country, but as locals benefit from their investment in shares of the foreign firm, the listing may become an AOF (Bell et al., 2012; Tupper et al., 2018).

Foreignness may also increase or decrease with institutional changes in either the host or the home country. AOF might be very high initially, for instance when a host country is eager to attract foreign investment for its superior technology or advanced management techniques, or even more broadly when a host country is dependent on foreign firms for its economic prosperity (Sethi et al., 2002), but such AOF may dissipate over time.

Finally, social and economic changes can affect host-country attitude toward foreign firms, engendering a change in LOF and AOF. For example, actors in host countries who believe that local firms engage in corrupt practices will be more likely to trust foreign firms from countries with better reputations for honesty. When that is the case, “honest country” MNE subsidiaries instantly acquire a legitimacy-related AOF (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999). MNEs may eventually lose that advantage either if local practices improve or if there is a scandal in the home country.

Taken together, foreignness is not a binary concept. As we have said, it varies with contexts and over time. Thus, foreignness needs to be explored at different levels and across different streams. In addition to examining foreignness at the regional, country, industry, firm, and expatriate levels, future research could creatively weave and integrate the various aspects and perspectives of the multiple streams of foreignness research. Such cross-fertilization would better capture the many aspects of foreignness. For instance, it would be interesting to jointly examine LOF and AOF (Sethi & Judge, 2009; Edman, 2016a; Pant & Ramachandran, 2017), home and host-country factors (Miller & Richards, 2002), local and global factors (Taussig, 2017), firm-level and country-level factors (Edman, 2016a, 2016b; Zhou & Guillén, 2016), market and non-market factors (Mithani, 2017; Kim, 2019; Siegel et al., 2019), and different kinds of foreign MNEs in the same host country (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008; Denk et al., 2012). Some may find it puzzling that MNEs can in the same host country both face LOF and enjoy AOF, but once one appreciates that foreignness is a multifaceted phenomenon, it is no longer a paradox. After all, the challenges faced by firms are rarely unidimensional, but often characterized by contradictions, conflicts, and significant tensions. As such, the paradoxical perspective on managerial research (Smith & Lewis, 2011) promises to be useful in tackling complex research problems, as demonstrated in Pant and Ramachandran’s (2017) account of how an MNE subsidiary is able to manage dual identities over time, either sequentially or simultaneously.

Integration of LOF and AOF