the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The role of ecosystem engineers in shaping the diversity and function of arid soil bacterial communities

Arielle M. Farrell

Adam Št'ovíček

Lusine Ghazaryan

Itamar Giladi

Osnat Gillor

Ecosystem engineers (EEs) are present in every environment and are known to strongly influence ecological processes and thus shape the distribution of species and resources. In this study, we assessed the direct and indirect effect of two EEs (perennial shrubs and ant nests), individually and combined, on the composition and function of arid soil bacterial communities. To that end, topsoil samples were collected in the Negev desert highlands during the dry season from four patch types: (1) barren soil; (2) under shrubs; (3) near ant nests; or (4) near ant nests situated under shrubs. The bacterial community composition and potential functionality were evaluated in the soil samples (14 replicates per patch type) using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing together with physico-chemical measures of the soil. We have found that the EEs affected the community composition differently. Barren patches supported a soil microbiome, dominated by Rubrobacter and Proteobacteria, while in EE patches Deinococcus-Thermus dominated. The presence of the EEs similarly enhanced the abundance of phototrophic, nitrogen cycle, and stress-related genes. In addition, the soil characteristics were altered only when both EEs were combined. Our results suggest that arid landscapes foster unique communities selected by patches created by each EE(s), solo or in combination. Although the communities' composition differs, they support similar potential functions that may have a role in surviving the harsh arid conditions. The combined effect of the EEs on soil microbial communities is a good example of the hard-to-predict non-additive features of arid ecosystems that merit further research.

- Article

(2221 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Hot desert environments are characterized by long droughts interspersed by intermittent and unpredictable rain events. Water and nutrients in hot desert environments are scarce and unevenly distributed across the land, resulting in patches of contrasting productivities. High-productivity patches, also called resource islands, are defined by large concentrations of organic matter and nutrients (Bachar et al., 2012; Ben-David et al., 2011; Schlesinger et al., 1996; West, 1981). These resource islands can be formed through the redistribution of nutrients and water by ecosystem engineers (EEs), such as perennial plants or invertebrates (Wilby et al., 2001; Wright et al., 2006). EEs are also known for impacting many components of a given environment, such as soil features, annuals distribution, or community composition of microorganisms (De Graaff et al., 2015; Oren et al., 2007).

An EE is an organism that, directly or indirectly, modifies the availability of resources to other organisms by transforming the physical state of abiotic and/or biotic components of the ecosystem sensu Jones et al. (1994). The impacts of EEs range from physical, through the creation of biogenic structures (e.g. tunnels) (Lavelle, 2002), to chemical, through the production of compounds that have physiological effects (e.g. root exudates) (Lavelle et al., 1992), to biological, through organism behaviour (e.g. seed dispersal) (Lavelle et al., 2006). In drylands, resources, such as nutrients or water, are often concentrated around EEs, boosting the development of diverse populations of annual plants and invertebrates (Wright and Upadhyaya, 1996) as well as microbial communities (Bachar et al., 2012; Ginzburg et al., 2008; Saul-Tcherkas and Steinberger, 2011). This taxonomical response to changes in the physico-chemical conditions is linked to the potential function of the community (Narayan et al., 2020). This implies that the variation in taxonomy by the presence of an EE could potentially be associated with changes in functionality.

In desert ecosystems, ants are a notable example of an EE (Ginzburg et al., 2008). They redistribute resources by tilling the soil, bringing soil from the deep layers to the upper layers (bioturbation), and by gathering, storing, and ejecting food items, such as plant material or dead invertebrates, in and around the nest (Filser et al., 2016; Folgarait, 1998; MacMahon et al., 2000). EEs in arid environments also include perennial shrubs (Callaway, 1995; Schlesinger and Pilmanis, 1998; Segoli et al., 2012; Shachak et al., 2008; Walker et al., 2001). Their root systems create a soil mound that traps litter and seeds, allowing for higher water infiltration. The root exudates increase the content of organic matter and the shrub canopies decrease evaporation, prolonging water availability following a rain event (Bachar et al., 2012). In addition, the presence of shrubs alters the course of water run-off (Oren et al., 2007), which impacts the locations of available water for soil microbial communities. In addition, root systems have their own microbiome, which interacts with the soil microbial community (Steven et al., 2014).

The roles of both ants and perennial shrubs as EEs were reported in various ecosystems (Facelli and Temby, 2002; Farji-Brener and Werenkraut, 2017; Frouz et al., 2003; Gosselin et al., 2016; Pariente, 2002; Schlesinger et al., 1996). However, we know little about their joint effect on arid ecosystems. We hypothesized that each EE would shape a unique soil bacterial community via changes in the soil physico-chemical properties. We further predicted that since shrub canopies and ant nests may affect soil properties differently, their combined effect on the microbial community is non-additive and thus cannot be predicted by the contributing components. To test our hypotheses, we explored arid soil bacterial microbiomes and soil chemical features during the dry season of 2015. We sampled four different patches: under Hammada scoparia shrubs; near the nest openings of the harvester ant Messor ebeninus; in combined patches of the ants' nests under shrubs; and in barren soil.

2.1 Sampling

The study was conducted in a long-term ecological research (LTER) site in the central Negev, Israel (Zin Plateau, 34∘80′ E, 30∘86′ N). It is characterized by 90 mm annual rainfall and average monthly temperatures fluctuating from 13 ∘C (January) to 35 ∘C (August). Vegetation is scarce and dominated by the perennial shrubs Hammada scoparia and Atriplex halimus (Gilad et al., 2004).

Sampling was conducted as previously described (Baubin et al., 2019) with slight modifications, such as the inclusion of Shrub & Nest samples. To summarize, we sampled four distinct patch types: (1) barren soil (Barren); (2) under the canopy of H. scoparia (Shrub); (3) 20–30 cm from the main opening of the nest of M. ebeninus (Nest); and (4) 20–30 cm from an ant nest's opening that was situated under a shrub canopy (Shrub & Nest). Samples were collected in October 2015, after an 8-month drought.

We sampled 14 random experimental blocks from each of the four patches (4 patch types ×14 blocks = 56 samples). The samples were collected using a scoop that was sterilized between each sampling using 70 % technical ethanol. Soil was collected from the top 5 cm after removal of the crust and debris. Three subsamples of ∼100 g were collected from each block and pooled together. In the lab, samples from two adjacent blocks were composite and homogenized using a 2 mm sieve. The samples were then separated for consecutive analyses: 15 g of each soil sample was stored in −80 ∘C for bacterial analysis, 25 g was used to determine the water content in the soil, and the rest was used for the measurements of physico-chemical properties.

2.2 DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing

Total nucleic acids were extracted from 0.5 g of soil as previously described (Angel, 2012), purified with the ExgeneTM Soil SV kit (GeneAll, Seoul, South Korea) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The 16S rRNA encoding genes V3–V4 region was amplified using 341F and 806R primer (Klindworth et al., 2013). The PCR consisted of 2.5 µL 10× standard buffer, 10 µM primers, 0.8 mM dNTPs, 0.4 µL DreamTaq DNA polymerase, 4 µL template, 1 mM bovine serum albumin (Takara, Kusatsu, Japan), and 12.6 µL Milli-Q water. Triplicate PCR reactions (95 ∘C for 30 s; 28 cycles of 95 ∘C for 15 s, 50 ∘C for 30 s, 68 ∘C for 30 s; 68 ∘C for 5 min) were pooled and amplicon concentration and purity were measured by electrophoresis (Nanodrop ND-1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The amplicon libraries were constructed and sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform (2×250, pair-end) at the Research Resources Centre at the University of Illinois.

2.3 Soil physico-chemical analysis

The physico-chemical parameters of the soil samples were assessed following the standard methods (SSSA, 1996). Water content was measured by gravimetry. Other parameters were measured as follows by the Gilat Hasade Services Laboratory (Moshav Gilat, Israel). The pH was measured in saturated soil extract (SSE). Phosphorus (P) was extracted by the Olsen method using a 0.5 M sodium bicarbonate solution (NaHCO3) and the absorbance of the final solution was measured at 880 nm using a spectrophotometer. Nitrate () and ammonium () were extracted with a 2 N potassium chloride (KCl) solution and measured at 520 and 660 nm, respectively. Organic matter (OM) content was determined by the Walkley–Black method using a dichromate oxidation () and the amount of oxidizable OM was measured at 600 nm.

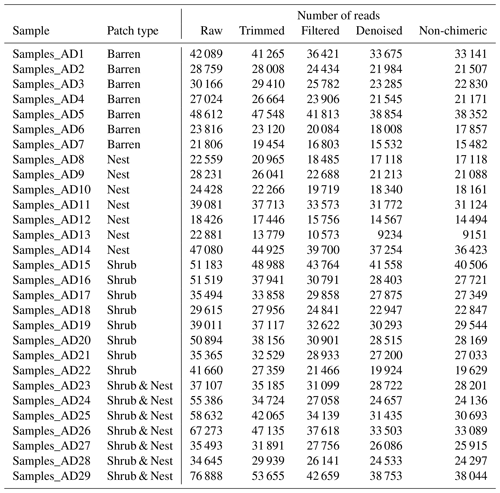

2.4 Bioinformatic analysis

The reads were quality-checked with MultiQC and trimmed using TrimGalore. Briefly, all reads with a quality of less than 20 and shorter than 150 bp were removed, and the rest were analysed further. The reads were then gathered into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) (99 % identity cutoff) and merged using Dada2 (Callahan et al., 2016) in QIIME2 (Bolyen et al., 2018) following the NeatSeq-Flow pipeline (Sklarz et al., 2018). ASV counts were normalized to equal sampling depth (9100 reads). The taxonomic assignment was done using Silva (version 132) (Quast et al., 2013) through QIIME2 and all non-bacterial data have been characterized as unclassified.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was done using R (R Core Team, 2016). To visualize the differences between patch types, a non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot was created using the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity and the significance of these differences was analysed using a non-parametric analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) (“vegan” package, Oksanen et al., 2014). The envfit function (“vegan” package, Oksanen et al., 2014) was applied on the NMDS data to evaluate the effect of soil parameters on the bacterial community. The NMDS was plotted using the “ggplot2” package (Wickham, 2016) and the arrows representing the effect of each soil parameter as well as the centroids for each patch type, calculated using envfit, were added to the plot. The bacterial data were analysed using the “phyloseq” package (McMurdie et al., 2017). The relative abundance, whenever higher than 0.05 %, of each phylum, class, and order was calculated and then plotted using a stacked bar plot (“ggplot2” package, Wickham, 2016). The significance of difference between patch types was assessed using a non-parametric test: a Kruskal–Wallis test and a post hoc Dunn test (Dinno, 2017; Dunn, 1964; Kruskal and Wallis, 1952). All sequences retrieved in this study were uploaded to BioProject (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject, last access: 30 September 2018) under the submission number PRJNA484096.

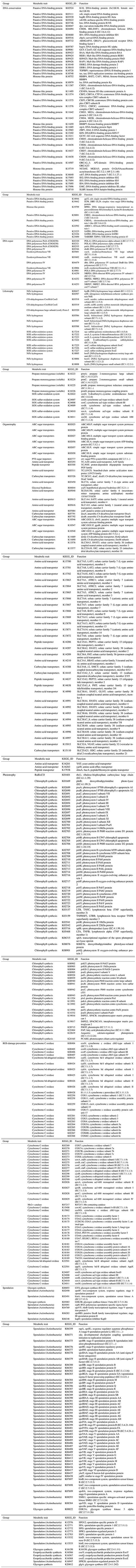

2.6 Functional prediction

The prediction of function of the 16S amplicons was done with Piphillin using the KEGG database (October 2018). Piphillin generates a genome abundance table that is normalized to the 16S rRNA copy number for each genome (Iwai et al., 2016; Narayan et al., 2020). To analyse the arid soil microbial functionality, we selected metabolisms and respective genes related to arid soil using groups and genes from the KEGG database (Kaneshisa and Goto, 2000). We selected steps in metabolic pathways for different methods of harvesting energy (organotrophy, lithotrophy, and phototrophy) (Cordero et al., 2019; Greening et al., 2016; León-Sobrino et al., 2019; Tveit et al., 2019), for parts of the nitrogen cycle (Galloway et al., 2004), and for the survival of the individual during a drought (DNA conservation and repair, sporulation, and reactive oxygen species (ROS)-damage prevention) (Borisov et al., 2013; Hansen et al., 2007; Henrikus et al., 2018; Preiss, 1984; Preiss and Sivak, 1999; Rajeev et al., 2013; Repar et al., 2012; Slade and Radman, 2011). Then, we looked for each step in the KEGG database and picked out genes of interest to build our own database. The assignment of function to the KEGG numbers was done in R. The significance of the differences between patch types in predicted functionalities was evaluated using a non-parametric test, a Kruskal–Wallis test and a post hoc Dunn test (Dinno, 2017; Dunn, 1964; Kruskal and Wallis, 1952), and boxplots were created in R.

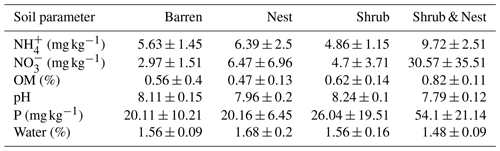

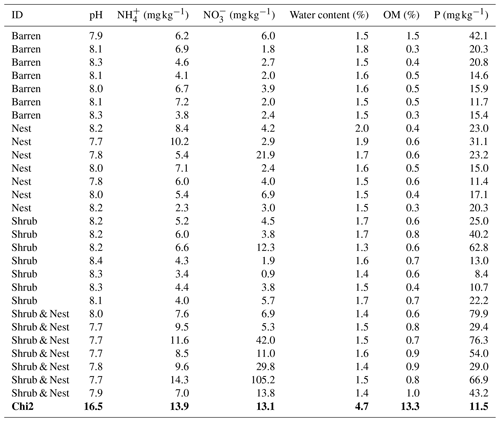

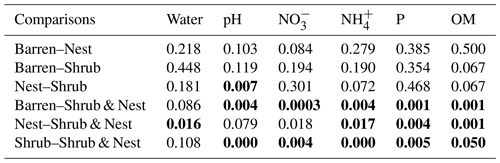

3.1 Soil physico-chemical characteristics

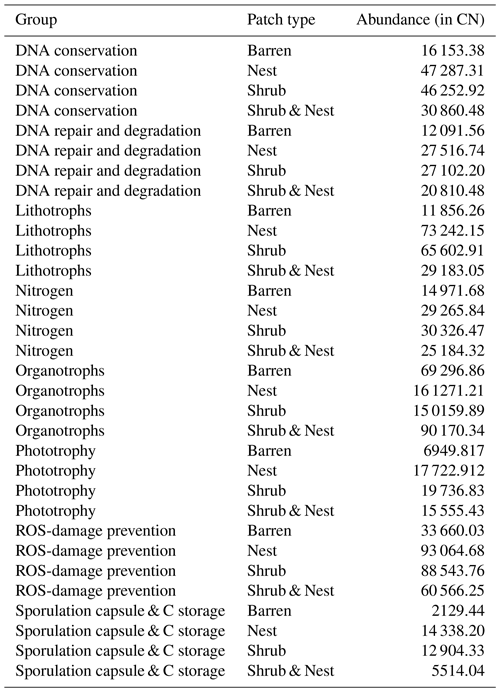

Table 1 depicts the differences in the soil characteristics (full list of values in Table A1) between the patches (barren, nest, shrub, and Shrub & Nest). Shrub & Nest patches have higher concentrations of and P (30 and 54 mg kg−1, respectively) than the average of the other patches combined (4.7 and 22 mg kg−1, respectively). When verifying with a Kruskal–Wallis test and a Dunn test on the values of these soil variables (Table A2), we see that the differences between patch types are significant (Shrub & Nest vs. all other patches, p<0.05). Patches with two EEs also have a significantly higher concentration of (9.72 mg kg−1) and OM (8.21 %) compared to all other patches ( mean: 5.62 mg kg−1, p value < 0.05; OM mean: 5.51 %, p≤0.05). However, the water content and pH did not show significant differences between patches (Table A2).

3.2 Beta diversity

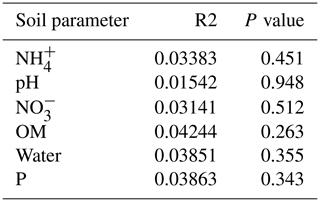

The summary of the sequence analysis can be found in Table A4. Dada2 analysis yielded 2318 ASVs and the ANOSIM results (Fig. 1, Table A3) suggest that there are significant differences in the microbial community between patch types (R=0.28; p=0.001). The envfit function shows that most soil parameters correlated with the barren patches but not with the other three patch types.

Figure 1Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) of the soil 16S microbial communities in the dry season under different patch types. The centroid for each patch type is represented by a dashed circle. The arrow vectors represent the effect of each soil physico-chemical characteristic on the bacterial community calculated with the envfit function. : nitrate, : ammonium, OM: organic matter content, P: phosphorus, water: water content. The patch types are significantly different from each other (ANOSIM, R=0.28247; p value = 0.001). P, OM, , and .

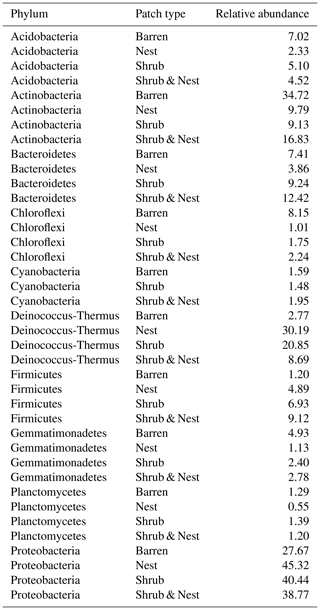

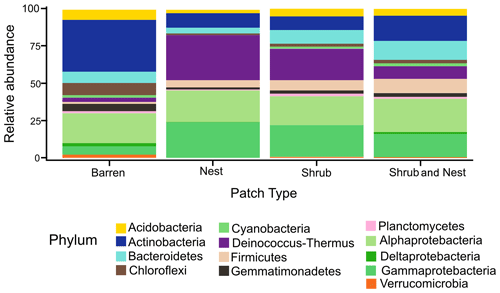

3.3 Community composition

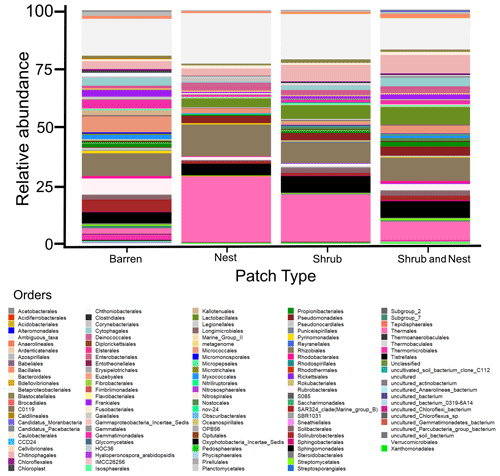

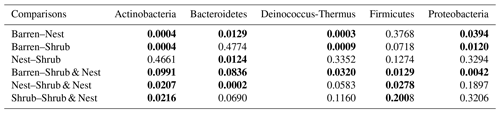

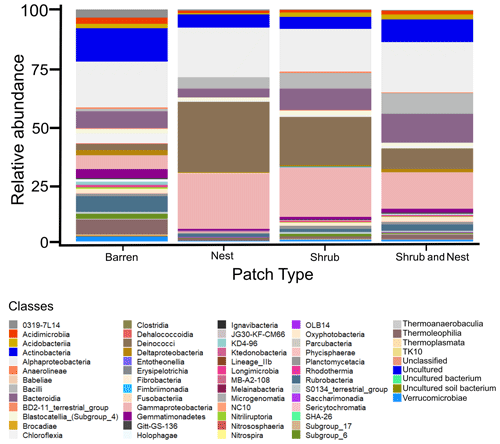

The community was mostly composed of Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Deinococcus-Thermus, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes (Fig. 2). The relative abundance for each phylum is detailed in Table A5. We focused on the results of the three main phyla: Actinobacteria, Deinococcus-Thermus, and Proteobacteria. Using pair-wise comparisons, we saw that shrub patches and nest patches had similar communities (no significant differences, p>0.05); therefore, we considered them to be single EE patches. For these patches, an average relative abundance of nest and shrub patches was used for statistical data. For the Actinobacteria phylum, patches with one EE had significantly lower relative abundance than barren patches (one EE: 9 % vs. Barren patch: 35 % p<0.005) or patches with two EEs (17 %, p value: 0.02). For the Deinococcus-Thermus phylum, barren patches had significantly lower relative abundance than patches with one or two EEs (Barren: 3 % vs. one EE: 25 % vs. two EEs: 9 %, p<0.05). A similar pattern was detected in the Proteobacteria phylum (Barren: 38 % vs. one EE: 44 % vs. two EEs: 39 %, p<0.05). Additionally, we looked at the next three most abundant phyla: Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Chloroflexi. For Firmicutes, the relative abundance of this phylum was significantly higher in the Shrub & Nest patch than in the Barren and Shrub patches. For Bacteroidetes, the Nest patch had a significantly lower relative abundance than the other patches. For Chloroflexi, there was a significant decrease in relative abundance in the Shrub, Nest, and Shrub & Nest patches compared to the Barren patch. All p values can be found in Table A6. The class and order plots show differences between patch types. However, the resolution is not high enough to enable us to draw significant conclusions (Figs. B1 and B2).

Figure 2Bar plot of the relative abundance (%) of the most abundant phyla in the soil microbial community in the dry season under different patch types (phyla with a relative abundance >0.05 %). The Proteobacteria have been separated into their classes (represented here in shades of green). The relative abundance of Deinococcus-Thermus increases when one EE is present, while the population of Actinobacteria decreases.

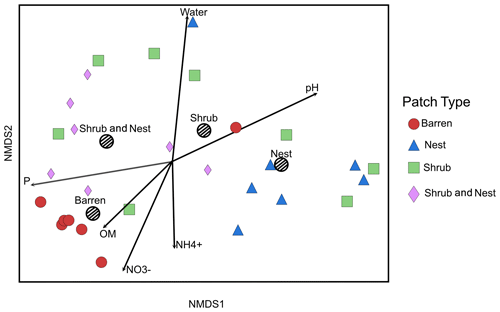

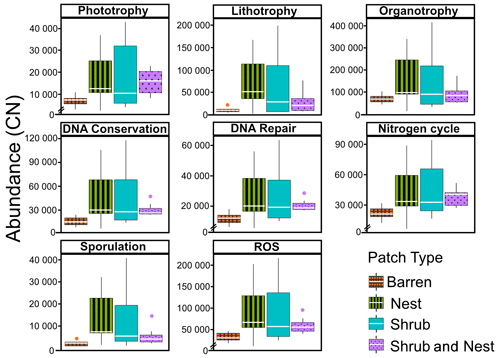

3.4 Functional prediction

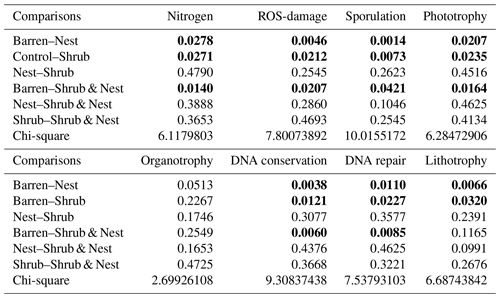

The abundance of each gene group has been normalized to the 16S rRNA copy number for each genome. The functional prediction results focus on eight distinct gene groups: phototrophy, lithotrophy, organotrophy, DNA conservation, DNA repair, nitrogen cycle, sporulation, and ROS-damage prevention (listed in Table A7). Figure 3 shows the pattern of the obtained functions. It shows higher abundances of the gene group encoding for DNA conservation, DNA repair, nitrogen metabolism, ROS-damage prevention, sporulation, and phototrophy in patches associated with at least one EE compared to the barren patches (Table A8). Therefore, we analysed the results as barren vs. average of the other three patch types that were not significantly different from one another (Table A9), and significant differences (p<0.04) between barren and EE patches were detected. The genes related to lithotrophy only differed between patches with one EE and the barren patches (p<0.03), but patches with two EEs were similar to the barren plots. Finally, for genes related to the organotrophy, there were no significant differences between the patches (p>0.05).

Figure 3Boxplots of the functional prediction of the 16S sequences. Each panel (boxplot) represents a different group of genes associated with a certain functionality. The full list of genes can be found in Table A7. The patch types are represented by distinct colours and patterns. The y axis is the abundance in copy number (CN) normalized to the 16S rRNA copy number for each genome.

In desert environments, during the dry season, a large portion of the microbial community is dormant or shows reduced metabolic activity (Bay et al., 2018; Cordero et al., 2019; Lennon and Jones, 2011; Schulze-Makuch et al., 2018). However, the presence of EEs enhances the potential for functions related to metabolism and to survival functions (Fig. 3). EEs create havens of resources and water, which can be affiliated with the concept of resource islands (Schlesinger and Pilmanis, 1998). However, their individual, and combined, effects do not always lead to significant changes in the composition of the soil microbial community (Fig. 2). While the soil parameters might be modified by the presence of both EEs, the microbial community might take a longer time to change due to their slow turnover in the dry season. However, these communities experience more habitable conditions due to the modulating effects of the EEs on the environmental conditions. The increase in the activity of gene groups can be explained by an increase in nutrients in the joint EE patches (Table 1).

Both Actinobacteria and Deinococcus-Thermus were abundant in all patches, but their relative abundances were negatively correlated. Each phylum featured a dominant genus that is well adapted to stressful conditions: Rubrobacter dominated the barren soil, while Deinococcus dominated the EE patches (Fig. 2 and Table A5). Rubrobacter are specialized in surviving strong desiccation and low nutrients (Bull, 2011; Ferreira et al., 1999), showing high relative abundance in arid barren soils of the Negev desert highlands (Meier et al., 2021). Deinococcus are versatile organisms, highly adapted to a wide range of extremes, such as radiations, temperatures, and xerification (Chanal et al., 2006; Prieur, 2007; Slade and Radman, 2011). This versatility allows them to thrive in EE patches as they can better adapt to perturbations compared to Rubrobacter.

Only the combination of EEs resulted in significant changes (p values: Table A2) in , P, and, to a lesser extent, NH, pH, and OM (values: Table A1). When located under a shrub, ants can increase their seed consumption, which enhances the amount of leftovers around the nest (Wagner, 1997) and increases the concentrations of and P. These macronutrients are important drivers of the biological processes, as they are often the limiting factors of microbial growth and activity in the terrestrial environments (FAO et al., 2020). The physico-chemical measures, including soil water content, OM, nitrogen, P, and pH, did not match the changes observed in bacterial composition or function (Tables A1, A2, and A9 and Fig. 1), as was previously reported (Angel et al., 2010; Bachar et al., 2012; Vonshak et al., 2018). Indeed, there was no significant link between the changes in the bacterial communities and the measured soil parameters (Table A10).

The EE patches analysed in this study share the same habitat and resources, but their impacts are distinct (Passarelli et al., 2014), and, thus, their joint impact is non-additive. The behaviour of each EE is important as it becomes a feature of the combined impact of both EEs (Alba-Lynn and Detling, 2008). However, the effect of both EEs together cannot be inferred from their individual environmental impact or from their mutual interaction (Gilad et al., 2004). Here, we investigated a sessile organism with a passive and slow impact (the perennial shrub) and compared it to a motile organism (the ants) with an active and transient impact. Ants may have both a short-term impact, through the seasonal accumulation of seeds and organic matter, and a lasting impact, due to the alternation of the nest mound which remains in the same place for decades (Wagner and Jones, 2004). We have previously proposed that the observed differences in communities could be mediated by microclimatic characteristics under shrub patches (Bachar et al., 2012). It has been reported that the desert dwarf shrubs affect the physical features of their immediate soil patch. Shrubs were shown to divert water flow and reduce evapotranspiration rates following rain events (Segoli et al., 2008; Whitford and Duval, 2002) and reduce temperature and radiation year round (Kidron, 2009). Likewise, ants aerate the soil, thus increasing infiltration during rain events (Berg and Steinberger, 2008), and mix the layers through bioturbation (Folgarait, 1998). Therefore, the prolonged water availability and altered physical conditions from the wet season may have lasting effects on the communities' structure (Baubin et al., 2019), shaping the composition and functions observed here (Figs. 2 and 3).

In this study, we focused on two EEs only, but there are many EEs in one ecosystem, and knowing their joint impact would help explain the nutrient turnover and the bacterial communities in this ecosystem. The main stress-resistant phyla (Actinobacteria and Deinococcus-Thermus) react differently to the presence of EEs. The presences of these EEs also lead to a higher potential activity in the microbial communities. However, even though they have similar impacts, when together, EEs have non-additive effects.

Table A1Soil characteristics data. NH and P show the highest discrepancy between Shrub & Nest patches and the other three types.

Table A2P values of the Dunn test between patch types on the soil characteristics variables. Bold numbers are significant (<0.05).

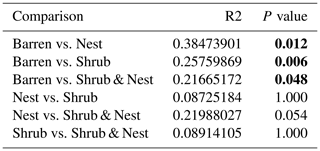

Table A3Results of the pair-wise adonis test between patch types. Bold numbers are significant (<0.05).

Table A6P values of the Dunn tests between patch types on the relative abundance of the five most abundant phyla. Bold numbers are significant (<0.05).

Table A9Chi-square values and p values of the Dunn tests between patches done on the functional prediction results. Bold numbers are significant (<0.05).

Figure B1Bar plot of the relative abundance (%) of the most abundant classes in the soil microbial community in the dry season under different patch types (classes with a relative abundance >0.05 %). The resolution is too low to draw significant conclusions.

The data (raw reads) are available in BioProject under the submission number PRJNA484096 at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA484096 (Baubin, 2018).

IG, OG, and AMF conceptualized and designed the methodology; AMF and AS collected the samples and metadata; LG and AMF did the laboratory work and sequencing; CB did the formal analysis, visualization, and data curation and wrote the manuscript; IG, OG, and CB did the reviewing and editing of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This research has been supported by the Koshland Foundation to Itamar Giladi and Osnat Gillor.

This paper was edited by Elizabeth Bach and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Alba-Lynn, C. and Detling, J. K.: Interactive disturbance effects of two disparate ecosystem engineers in North American shortgrass steppe, Oecologia, 157, 269–278, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-008-1068-0, 2008.

Angel, R.: Total Nucleic Acid Extraction from Soil, https://doi.org/10.1038/protex.2012.046, 2012.

Angel, R., Soares, M. I. M., Ungar, E. D., and Gillor, O.: Biogeography of soil archaea and bacteria along a steep precipitation gradient, ISME J., 4, 553–563, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2009.136, 2010.

Bachar, A., Soares, M. I. M., and Gillor, O.: The effect of resource islands on abundance and diversity of bacteria in arid soils, Microb. Ecol., 63, 694–700, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-011-9957-x, 2012.

Baubin, C.: Soil metagenome Raw sequence reads, NCBI [data set], available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA484096, last access: 30 September 2018.

Baubin, C., Farrell, A. M., Št'ovíček, A., Ghazaryan, L., Giladi, I., and Gillor, O.: Seasonal and spatial variability in total and active bacterial communities from desert soil, Pedobiologia, 74, 7–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedobi.2019.02.001, 2019.

Bay, S., Ferrari, B., and Greening, C.: Life without water: How do bacteria generate biomass in desert ecosystems?, Microbiology Australia, 39, 28–32, https://doi.org/10.1071/MA18008, 2018.

Ben-David, E. A., Zaady, E., Sher, Y., and Nejidat, A.: Assessment of the spatial distribution of soil microbial communities in patchy arid and semi-arid landscapes of the Negev Desert using combined PLFA and DGGE analyses, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 76, 492–503, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01075.x, 2011.

Berg, N. and Steinberger, Y.: Role of perennial plants in determining the activity of the microbial community in the Negev Desert ecosystem, Soil Biol. Biochem., 40, 2686–2695, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.07.019, 2008.

Bolyen, E., Rideout, J. R., Dillon, M. R., Bokulich, N. A., Abnet, C., Al-Ghalith, G. A., Alexander, H., Alm, E. J., Arumugam, M., Asnicar, F., Bai, Y., Bisanz, J. E., Bittinger, K., Brejnrod, A., Brislawn, C. J., Brown, C. T., Callahan, B. J., Caraballo-Rodríguez, A. M., Chase, J., Cope, E., Da Silva, R., Dorrestein, P. C., Douglas, G. M., Durall, D. M., Duvallet, C., Edwardson, C. F., Ernst, M., Estaki, M., Fouquier, J., Gauglitz, J. M., Gibson, D. L., Gonzalez, A., Gorlick, K., Guo, J., Hillmann, B., Holmes, S., Holste, H., Huttenhower, C., Huttley, G., Janssen, S., Jarmusch, A. K., Jiang, L., Kaehler, B., Kang, K. Bin, Keefe, C. R., Keim, P., Kelley, S. T., Knights, D., Koester, I., Kosciolek, T., Kreps, J., Langille, M. G. I., Lee, J., Ley, R., Liu, Y.-X., Loftfield, E., Lozupone, C., Maher, M., Marotz, C., Martin, B. D., McDonald, D., McIver, L. J., Melnik, A. V, Metcalf, J. L., Morgan, S. C., Morton, J., Naimey, A. T., Navas-Molina, J. A., Nothias, L. F., Orchanian, S. B., Pearson, T., Peoples, S. L., Petras, D., Preuss, M. L., Pruesse, E., Rasmussen, L. B., Rivers, A., Robeson Michael S, I. I., Rosenthal, P., Segata, N., Shaffer, M., Shiffer, A., Sinha, R., Song, S. J., Spear, J. R., Swafford, A. D., Thompson, L. R., Torres, P. J., Trinh, P., Tripathi, A., Turnbaugh, P. J., Ul-Hasan, S., van der Hooft, J. J. J., Vargas, F., Vázquez-Baeza, Y., Vogtmann, E., von Hippel, M., Walters, W., Wan, Y., Wang, M., Warren, J., Weber, K. C., Williamson, C. H. D., Willis, A. D., Xu, Z. Z., Zaneveld, J. R., Zhang, Y., Zhu, Q., Knight, R., and Caporaso, J. G.: QIIME 2: Reproducible, interactive, scalable, and extensible microbiome data science, PeerJ Preprints., 6, e27295v2, https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.27295v2, 2018.

Borisov, V. B., Forte, E., Davletshin, A., Mastronicola, D., Sarti, P., and Giuffrè, A.: Cytochrome bd oxidase from Escherichia coli displays high catalase activity: An additional defense against oxidative stress, FEBS Lett., 587, 2214–2218, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2013.05.047, 2013.

Bull, A. T.: Actinobacteria of the Extremobiosphere, in: Extremophiles Handbook, edited by: Horikoshi, K., Springer Japan, Tokyo, 1203–1240, 2011.

Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J., Rosen, M. J., Han, A. W., Johnson, A. J. A., and Holmes, S. P.: DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data, Nat. Methods, 13, 581–583, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3869, 2016.

Callaway, R. M.: Positive interactions among plants, Bot. Rev., 61, 306–349, 1995.

Chanal, A., Chapon, V., Benzerara, K., Barakat, M., Christen, R., Achouak, W., Barras, F., and Heulin, T.: The desert of Tataouine: an extreme environment that hosts a wide diversity of microorganisms and radiotolerant bacteria, Environ. Microbiol., 8, 514–525, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00921.x, 2006.

Cordero, P. R. F., Bayly, K., Man Leung, P., Huang, C., Islam, Z. F., Schittenhelm, R. B., King, G. M., and Greening, C.: Atmospheric carbon monoxide oxidation is a widespread mechanism supporting microbial survival, ISME J., 13, 2868–2881, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-019-0479-8, 2019.

de Graaff, M.-A., Adkins, J., Kardol, P., and Throop, H. L.: A meta-analysis of soil biodiversity impacts on the carbon cycle, SOIL, 1, 257–271, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-1-257-2015, 2015.

Dinno, A.: Package “dunn.test,” CRAN Repos., 1–7, available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dunn.test/dunn.test.pdf (last access: 5 March 2021), 2017.

Dunn, O. J.: Multiple Comparisons Using Rank Sums, Technometrics, 6, 241–252, 1964.

Facelli, J. M. and Temby, A. M.: Multiple effects of shrubs on annual plant communities in arid lands of South Australia, Austral. Ecol., 27, 422–432, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-9993.2002.01196.x, 2002.

FAO, ITPS, GSBI, SCBD and EC: State of knowledge of soil biodiversity – Status, challenges and potentialities, Report 2020, 2020.

Farji-Brener, A. G. and Werenkraut, V.: The effects of ant nests on soil fertility and plant performance: a meta-analysis, J. Anim. Ecol., 86, 866–877, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12672, 2017.

Ferreira, A. C., Nobre, M. F., Moore, E., Rainey, F. A., Battista, J. R., and Da Costa, M. S.: Characterization and radiation resistance of new isolates of Rubrobacter radiotolerans and Rubrobacter xylanophilus, Extremophiles, 3, 235–238, https://doi.org/10.1007/s007920050121, 1999.

Filser, J., Faber, J. H., Tiunov, A. V., Brussaard, L., Frouz, J., De Deyn, G., Uvarov, A. V., Berg, M. P., Lavelle, P., Loreau, M., Wall, D. H., Querner, P., Eijsackers, H., and Jiménez, J. J.: Soil fauna: key to new carbon models, SOIL, 2, 565–582, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-2-565-2016, 2016.

Folgarait, P.: Ant biodiversity to ecosystem functioning: a review, Biodivers. Conserv., 7, 1121–1244, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008891901953, 1998.

Frouz, J., Holec, M., and Kalčík, J.: The effect of Lasius niger (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) ant nest on selected soil chemical properties, Pedobiologia, 47, 205–212, https://doi.org/10.1078/0031-4056-00184, 2003.

Galloway, J. N., Dentener, F. J., Capone, D. G., Boyer, E. W., Howarth, R. W., Seitzinger, S. P., Asner, G. P., Cleveland, C. C., Green, P. A., Holland, E. A., Karl, D. M., Michaels, A. F., Porter, J. H., Townsend, A. R., and Vörösmarty, C. J.: Nitrogen cycles: past, present, and future, Biogeochemistry, 70, 153–226, 2004.

Gilad, E., von Hardenberg, J., Provenzale, A., Shachak, M., and Meron, E.: Ecosystem Engineers: From Pattern Formation to Habitat Creation, Phys. Rev. Lett., 93, 098105, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.098105, 2004.

Ginzburg, O., Whitford, W. G., and Steinberger, Y.: Effects of harvester ant (Messor spp.) activity on soil properties and microbial communities in a Negev Desert ecosystem, Biol. Fert. Soils, 45, 165–173, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-008-0309-z, 2008.

Gosselin, E. N., Holbrook, J. D., Huggler, K., Brown, E., Vierling, K. T., Arkle, R. S., and Pilliod, D. S.: Ecosystem engineering of harvester ants: effects on vegetation in a sagebrush-steppe ecosystem, West. N. Am. Naturalist, 76, 82–89, https://doi.org/10.3398/064.076.0109, 2016.

Greening, C., Biswas, A., Carere, C. R., Jackson, C. J., Taylor, M. C., Stott, M. B., Cook, G. M., and Morales, S. E.: Genomic and metagenomic surveys of hydrogenase distribution indicate H2 is a widely utilised energy source for microbial growth and survival, ISME J., 10, 761–777, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2015.153, 2016.

Hansen, B. B., Henriksen, S., Aanes, R., and Sæther, B. E.: Ungulate impact on vegetation in a two-level trophic system, Polar Biol., 30, 549–558, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-006-0212-8, 2007.

Henrikus, S. S., Wood, E. A., McDonald, J. P., Cox, M. M., Woodgate, R., Goodman, M. F., van Oijen, A. M., and Robinson, A.: DNA polymerase IV primarily operates outside of DNA replication forks in Escherichia coli, PLoS Genet., 14, 1–29, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1007161, 2018.

Iwai, S., Weinmaier, T., Schmidt, B. L., Albertson, D. G., Poloso, N. J., Dabbagh, K., and DeSantis, T. Z.: Piphillin: Improved prediction of metagenomic content by direct inference from human microbiomes, PLoS One, 11, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166104, 2016.

Jones, C. G., Lawton, J. H., and Shachak, M.: Organisms as Ecosystem Engineers, Oikos, 69, 373–386, 1994.

Kaneshisa, M. and Goto, S.: KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 27–30, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27, 2000.

Kidron, G. J.: The effect of shrub canopy upon surface temperatures and evaporation in the Negev Desert, Earth Surf. Proc. Land., 34, 123–132, 2009.

Klindworth, A., Pruesse, E., Schweer, T., Peplies, J., Quast, C., Horn, M., Glöckner, F. O., and Glockner, F. O.: Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies, Nucleic Acids Res., 41, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks808, 2013.

Kruskal, W. H. and Wallis, W. A.: Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis, J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 47, 583–621, https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1952.10483441, 1952.

Lavelle, P.: Functional domains in soils, Ecol. Res., 17, 441–450, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1703.2002.00509.x, 2002.

Lavelle, P., Blanchart, E., Martin, A., Spain, A. V., and Martin, S.: Impact of Soil Fauna on the Properties of Soils in the Humid Tropics, in: SSSA Spec. Publ., Vol. 29, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaspecpub29.c9, 1992.

Lavelle, P., Decaëns, T., Aubert, M., Barot, S., Blouin, M., Bureau, F., Margerie, P., Mora, P., and Rossi, J. P.: Soil invertebrates and ecosystem services, Eur. J. Soil Biol., 42, Suppl. 1, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2006.10.002, 2006.

Lennon, J. T. and Jones, S. E.: Microbial seed banks: The ecological and evolutionary implications of dormancy, Nat. Rev. Microbiol., 9, 119–130, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2504, 2011.

León-Sobrino, C., Ramond, J. B., Maggs-Kölling, G., and Cowan, D. A.: Nutrient acquisition, rather than stress response over diel cycles, drives microbial transcription in a hyper-arid Namib desert soil, Front. Microbiol., 10, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01054, 2019.

MacMahon, J. A., Mull, J. F., and Crist, T. O.: Harvester ants (Pogonomyrmex spp.): their community and ecosystem influences, Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst., 31, 265–291, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.265, 2000.

McMurdie, P. J., Holmes, S., Jordan, G., and Chamberlain, S.: Phyloseq: handling and analysis of high-throughput microbiome census data, 2017.

Meier, D. V., Imminger, S., Gillor, O., and Woebken, D.: Distribution of Mixotrophy and Desiccation Survival Mechanisms across Microbial Genomes in an Arid Biological Soil Crust Community, mSystems, 6, 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00786-20, 2021.

Narayan, N. R., Weinmaier, T., Laserna-Mendieta, E. J., Claesson, M. J., Shanahan, F., Dabbagh, K., Iwai, S., and Desantis, T. Z.: Piphillin predicts metagenomic composition and dynamics from DADA2- corrected 16S rDNA sequences, BMC Genomics, 21, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-6537-9, 2020.

Oksanen, J., Blanchet, F. G., Kindt, R., Legen-, P., Minchin, P. R., Hara, R. B. O., Simpson, G. L., Solymos, P., and Stevens, M. H. H.: Package “vegan”, ISBN 0-387-95457-0, 2014.

Oren, Y., Perevolotsky, A., Brand, S., and Shachak, M.: Livestock and engineering network in the Israeli Negev: Implications for ecosystem management, in: Ecosystem Engineers, Vol. 4, Elsevier Inc., 323–342, 2007.

Pariente, S.: Spatial patterns of soil moisture as affected by shrubs, in different climatic conditions, Environ. Monit. Assess., 73, 237–251, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013119405441, 2002.

Passarelli, C., Olivier, F., Paterson, D. M., Meziane, T., and Hubas, C.: Organisms as cooperative ecosystem engineers in intertidal flats, J. Sea Res., 92, 92–101, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seares.2013.07.010, 2014.

Preiss, J.: Bacterial glycogen synthesis and its regulation, Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 38, 419–458, 1984.

Preiss, J. and Sivak, M.: 3.14 – Starch and Glycogen Biosynthesis, edited by: Barton, S. D., Nakanishi, K., and Meth-Cohn, O. B. T., Pergamon, Oxford, 441–495, 1999.

Prieur, D.: An Extreme Environment on Earth: Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vents. Lessons for Exploration of Mars and Europa, in: Lectures in Astrobiology: Volume II, edited by: Gargaud, M., Martin, H., and Claeys, P., Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 319–345, 2007.

Quast, C., Pruesse, E., Yilmaz, P., Gerken, J., Schweer, T., Yarza, P., Peplies, J., and Glöckner, F. O.: The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools, Nucleic Acids Res., 41, D590–D596, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1219, 2013.

R Core Team, I.: R: A language and environment for statistical computing, 2016.

Rajeev, L., Da Rocha, U. N., Klitgord, N., Luning, E. G., Fortney, J., Axen, S. D., Shih, P. M., Bouskill, N. J., Bowen, B. P., Kerfeld, C. A., Garcia-Pichel, F., Brodie, E. L., Northen, T. R., and Mukhopadhyay, A.: Dynamic cyanobacterial response to hydration and dehydration in a desert biological soil crust, ISME J., 7, 2178–2191, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.83, 2013.

Repar, J., Briski, N., Buljubašić, M., Zahradka, K., and Zahradka, D.: Exonuclease VII is involved in “reckless” DNA degradation in UV-irradiated Escherichia coli, Mutat. Res., 750, 96–104, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrgentox.2012.10.005, 2012.

Saul-Tcherkas, V. and Steinberger, Y.: Soil microbial diversity in the vicinity of a Negev desert shrub-Reaumuria negevensis, Microb. Ecol., 61, 64–81, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-010-9763-x, 2011.

Schlesinger, W. H. and Pilmanis, A. M.: Plant-soil interactions in deserts, Biogeochemistry, 42, 169–187, 1998.

Schlesinger, W. H., Raikks, J. A., Hartley, A. E., and Cross, A. F.: On the spatial pattern of soil nutrients in desert ecosystems, Ecology, 77, 364–374, https://doi.org/10.2307/2265615, 1996.

Schulze-Makuch, D., Wagner, D., Kounaves, S. P., Mangelsdorf, K., Devine, K. G., de Vera, J.-P., Schmitt-Kopplin, P., Grossart, H.-P., Parro, V., Kaupenjohann, M., Galy, A., Schneider, B., Airo, A., Frösler, J., Davila, A. F., Arens, F. L., Cáceres, L., Cornejo, F. S., Carrizo, D., Dartnell, L., DiRuggiero, J., Flury, M., Ganzert, L., Gessner, M. O., Grathwohl, P., Guan, L., Heinz, J., Hess, M., Keppler, F., Maus, D., McKay, C. P., Meckenstock, R. U., Montgomery, W., Oberlin, E. A., Probst, A. J., Sáenz, J. S., Sattler, T., Schirmack, J., Sephton, M. A., Schloter, M., Uhl, J., Valenzuela, B., Vestergaard, G., Wörmer, L., and Zamorano, P.: Transitory microbial habitat in the hyperarid Atacama Desert, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 115, 2670–2675, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1714341115, 2018.

Segoli, M., Ungar, E. D., and Shachak, M.: Shrubs enhance resilience of a semi-arid ecosystem by engineering and regrowth, Ecohydrology, 1, 330–339, 2008.

Segoli, M., Ungar, E. D., Giladi, I., Arnon, A., and Shachak, M.: Untangling the positive and negative effects of shrubs on herbaceous vegetation in drylands, Landscape Ecol., 27, 899–910, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-012-9736-1, 2012.

Shachak, M., Boeken, B., Groner, E., Kadmon, R., Lubin, Y., Meron, E., Ne'eman, G., Perevolotsky, A., Shkedy, Y., and Ungar, E. D.: Woody species as landscape modulators and their effect on biodiversity patterns, Bioscience, 58, 209–221, https://doi.org/10.1641/B580307, 2008.

Sklarz, M. Y., Levin, L., Gordon, M., and Chalifa-Caspi, V.: NeatSeq-Flow: A Lightweight High Throughput Sequencing Workflow Platform for Non-Programmers and Programmers alike, bioRxiv, 173005, https://doi.org/10.1101/173005, 2018.

Slade, D. and Radman, M.: Oxidative Stress Resistance in Deinococcus radiodurans, Microbiol. Mol. Biol. R.,75, 133–191, https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.00015-10, 2011.

SSSA: Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 3 Chemical methods, 5.3, edited by: Sparks, D. L., Page, A. L., A, H. P., Loeppert, R. H., Soltanpour, P. N., Tabatabai, M. A., Johnson, C. T., and Sumner, M. E., 1390 pp., 1996.

Steven, B., Gallegos-Graves, L. V., Yeager, C., Belnap, J., and Kuske, C. R.: Common and distinguishing features of the bacterial and fungal communities in biological soil crusts and shrub root zone soils, Soil Biol. Biochem., 69, 302–312, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOILBIO.2013.11.008, 2014.

Tveit, A. T., Hestnes, A. G., Robinson, S. L., Schintlmeister, A., Dedysh, S. N., Jehmlich, N., Von Bergen, M., Herbold, C., Wagner, M., Richter, A., and Svenning, M. M.: Widespread soil bacterium that oxidizes atmospheric methane, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 8515–8524, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1817812116, 2019.

Vonshak, A., Sklarz, M. Y., Hirsch, A. M., and Gillor, O.: Perennials but not slope aspect affect the diversity of soil bacterial communities in the northern Negev Desert, Israel, Soil Res., 56, 123–128, https://doi.org/10.1071/SR17010, 2018.

Wagner, D.: The Influence of Ant Nests on Acacia Seed Production, Herbivory and Soil Nutrients, J. Ecol., 85, 83–93, https://doi.org/10.2307/2960629, 1997.

Wagner, D. and Jones, J. B.: The Contribution of Harvester Ant Nests, Pogonomyrmex rugosus (Hymenoptera, Formicidae), to Soil Nutrient Stocks and Microbial Biomass in the Mojave Desert, Environ. Entomol., 33, 599–607, https://doi.org/10.1603/0046-225X-33.3.599, 2004.

Walker, L. R., Thompson, D. B., and Landau, F. H.: Experimental manipulations of fertile islands and nurse plant effects in the Mojave Desert, USA, West. N. Am. Naturalist, 61, 25–35, 2001.

West, N. E.: Nutrient cycling in desert ecosystems, in: Arid land ecosystems, Vol. 2, Structure, functioning and management, edited by: Goodall, D. W., Perry, R. A., and Howes, K. M. W., Cambridge University Press, Cabridge, UK, ISBN: 9780521229883, 301–324, 1981.

Whitford, W. G. and Duval, B. D.: Ecology of Desert Systems, Academic Press Inc, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-8809(02)00198-6, 2002.

Wickham, H.: Ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis, 2016.

Wilby, A., Shachak, M., and Boeken, B.: Integration of ecosystem engineering and trophic effects of herbivores, Oikos, 92, 436–444, https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0706.2001.920305.x, 2001.

Wright, J. P., Jones, C. G., Boeken, B., and Shachak, M.: Predictability of ecosystem engineering effects on species richness across environmental variability and spatial scales, Shrub mound effects on annual plant diversity, J. Ecol., 94, 815–824, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2006.01132.x, 2006.

Wright, S. F. and Upadhyaya, A.: Extraction of an abundant and unusual protein from soil and comparison with hyphal protein of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, Soil Sci., 161, 575–586, https://doi.org/10.1097/00010694-199609000-00003, 1996.