Abstract

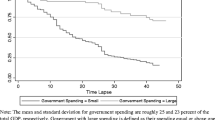

When should we expect compliance with international human rights norms? Previous literature on the causal mechanisms underlying compliance have focused independently on the roles of state willingness, thought of as the preferences of the regime leadership, and on state capacity, in improving human rights practices within a state. We build an argument that neither of these factors are sufficient on their own to improve compliance with human rights norms. Instead, improved human rights practices require both “the will and the way.” Our central hypothesis is that capacities and willingness, acting jointly, are key determinants of improvements in compliance with international human rights norms. The paper confirms this proposition using two-staged and single-stage regression models and a time-series cross-sectional approach at the country-year level. A highly capable bureaucracy and a state that has signaled its willingness through the acceptance of individual complaint and inquiry procedures in the UN treaty regime are jointly necessary for improved human rights practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See also Hill (2010) and Fariss (2014) for evidence of positive and unconditional relationships between some human rights treaties and human rights compliance.

We understand compliance as the respect of human rights norms in practice. For example, a state complies with international human rights norms when it abstains from torturing, executing or disappearing people; or when it follows due process or impedes violence against women. Compliance, of course, is not a matter of all or nothing, but of degrees. Compliance is sometimes understood as the implementation of the decisions of international human rights organs and bodies. For example, the implementation of the specific remedies established in a ruling of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. But we consider that it is important to differentiate between implementation of decisions and compliance with norms. Implementing a decision implies putting in practice concrete decisions of international human rights organs and bodies. Of course, the implementation of these decisions is expected to contribute to compliance (most likely in the mid to long terms), but it is not equivalent to it. A country can implement an international court’s decision regarding a specific case of enforced disappearance, but still perpetrate enforced disappearances. Implementation of decisions is more specific, whereas compliance implies a broader and consistent long-term abidance to human rights norms (cf. Huneeus 2011 and Hillebrecht 2012).

In a case study on judicial decisions in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Lake (2014: 515) found the opposite—that is, that limited statehood has “created openings” for transnational actors to have a direct or indirect impact on the delivery of public goods (such as the administration of justice) which has resulted in “surprisingly progressive human rights outcomes”. For a normative argument on the human rights obligations of non-state actors in areas of limited statehood, see Jacob et al. 2012.

As a robustness test, we also ran all models with the CIRI Human Rights Dataset physical integrity rights index. These results generally reinforce our findings using the Fariss (2014) measure and are available in our online appendix.

These nine core human rights treaties are the (1) Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR), the (2) Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the (3) Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), the (4) Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD), the (5) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), the (6) Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (CPED), the (7) Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (CESCR), the (8) Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), and (9) the Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (CMW). Our focus on these nine treaties as the core of the UN human rights treaty system reflects the classification of the UN Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights. See http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Indicators/Pages/HRIndicatorsIndex.aspx

Information was gathered in late 2017 and early 2018 from the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights website entitled “State of Ratification Interactive Dashboard” (https://indicators.ohchr.org/). We used the underlying data Excel files that are found on the dashboard website.

We also ran models where we restricted our focus to only the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), and the Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (CPED), as these three treaties could be argued to most closely related to our dependent variable. These results were also largely consistent with the results shown here and are available by request. Although this is an important robustness test, we argue that our expanded focus on all nine core human rights treaties is better in line with our central concept of willingness. In addition, many human rights treaties that are not focused exclusively on physical integrity rights still outline physical integrity rights in their provisions.

To our knowledge, the inter-state procedure has been used three times and in the framework of only one treaty body, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD). In March 2018, Qatar submitted two communications, one against the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the other one against the United Arab Emirates; and in April 2018, the State of Palestine submitted a communication against Israel. The CERD Committee is currently processing the three communications. As of the end of 2020, it has adopted favorable decisions regarding its jurisdiction on the three communications and also it adopted decisions on admissibility regarding the two communications submitted by Qatar. To our knowledge, the CERD Committee has not made a decision on admissibility yet on the communication by Palestine. Based on its rare usage and the newness of these three communications, which are still being processed, the inter-state procedure is not included in our analysis. See https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/CERD/Pages/InterstateCommunications.aspx and http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/TBPetitions/Pages/HRTBPetitions.aspx

Models with additional controls for civil society participation, human rights INGOs, and aid from states and intergovernmental organizations are included in our online appendix. Our main findings continue to hold.

Our main results do not hold when we include both fixed effects on country and fixed effects on year (two-way fixed effects). In general, we think a fixed effects approach is unwise for our analysis for a number of reasons. First, as Wooldridge (2012) discusses, fixed effects do not allow for the inclusion of covariates that do not vary over time, a worrisome concern for many of the instruments used in Cole (2012). Second, we are theoretically interested in how our key variables of interest influence human rights practices on average across countries, as opposed to how our key variables affect changes in particular countries, which would be a better justification for the use of fixed effects. Further, tests of autocorrelation show that there is serial correlation in the model. We feel the inclusion of a lagged dependent variable is much more important than running a fixed effects model and, as Nickell (1981) points out, the inclusion of fixed effects and a lagged dependent variable lead to potential bias in a sample with a relatively short timeframe.

References

Acemoglu, Daron, Camilo García-Jimeno, and James A. Robinson. “The Role of State Capacity in Economic Development” The Political Economist 11, no. 1 (2015): 7-9.

Anaya-Muñoz, Alejandro. “Bringing Willingness Back In: State Capacities and the Human Rights Compliance Deficit in Mexico”, Human Rights Quarterly 41, no. 2, (2019): 441–464.

Anaya-Muñoz, Alejandro, Hector M. Nuñez & Aldo F. Ponce. “Setting the agenda: Social influence in the effects of the Human Rights Committee in Latin America and Central and Eastern Europe”, Journal of Human Rights 17, no. 2 (2019): 229-244.

Börzel, Tanja A., and Thomas Risse. “Human Rights in Areas of Limited Statehood: The New Agenda.” Risse, Thomas, Stephen C. Ropp and Kathryn Sikkink. The Persistent Power of Human Rights: From Commitment to Compliance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, (2013): 63–84.

Brinkerhoff, Derick (2000) “Political Will for Anticorruption Efforts. An Analytical Framework." Public Administration Development 20 (2000): 239–252.

Brysk, Alison. "From above and below. Social movements, international system and human rights in Argentina." Comparative Political Studies 26, no. 3 (1993): 259-285.

Brysk, Alison. The Politics of Human Rights in Argentina. Protest, Change and Democratization. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press (1994a).

Brysk, Alison. “The Politics of Measurement: The Contested Count of the Disappeared in Argentina”, Human Rights Quarterly, 16 (1994b), pp. 676-692.

Byrnes, Andrew, and Jane Connors. "Enforcing the human rights of women: A complaints procedure for the women's convention." Brook. J. Int'l L.21 (1995): 679.

Cardenas, Sonia. Conflict and Compliance. State Responses to International Human Rights Pressure. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press (2007).

Chayes, Abram, and Antonia Chayes. “On compliance.” International Organization 47, no. 2 (1993): 175-205.

Cingranelli, D. L., D. L. Richards, and K. Chad Clay. "CIRI Human Rights Data Project." (2014).

Cole, Wade M. “Hard and Soft Commitments to Human Rights Treaties, 1966–2000” Sociological Forum 24, no. 3 (2009): 563–588.

Cole, Wade M. “Mind the Gap: State Capacity and the Implementation of Human Rights Treaties.” International Organization 62, no. 2 (2015): 405-441.

Cole, Wade M. “Managing to mitigate abuse: Bureaucracy, democracy, and human rights, 1984 to 2010.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 57, no. 1-2 (2016): 69–97.

Cole, Wade M. "Human rights as myth and ceremony? Reevaluating the effectiveness of human rights treaties, 1981–2007." American Journal of Sociology 117, no. 4 (2012): 1131-1171.

Conrad, Courtenay R., and Emily Hencken Ritter. "Treaties, tenure, and torture: The conflicting domestic effects of international law." The Journal of Politics 75, no. 2 (2013): 397–409.

Durbin, James. "Errors in variables." Revue de l'institut International de Statistique (1954): 23–32.

Englehart, Neil A. "State Capacity, State Failure, and Human Rights." Journal of Peace Research 46, no. 2 (2009): 163-180.

Fariss, Christopher J. "Respect for human rights has improved over time: Modeling the changing standard of accountability." American Political Science Review 108, no. 2 (2014): 297-318.

Freedom House. (2018). Freedom in the world. 2018.

Gleditsch, Nils Petter, Peter Wallensteen, Mikael Eriksson, Margareta Sollenberg, and Håvard Strand. "Armed conflict 1946–2001: A new dataset." Journal of peace research 39, no. 5 (2002): 615–637.

Grewal, Sharanbir and Erik Voeten. “Are New Democracies Better Human Rights Compliers?”, International Organization 69, no. 2 (2015): 497-518.

Hafner-Burton, Emilie M., and Kiyoteru Tsutsui. "Human Rights in a Globalizing World: The Paradox of Empty Promises." American Journal of Sociology 110, no. 5 (2005): 1373-1411.

Hathaway, Oona A. "Do human rights treaties make a difference?" The Yale Law Journal 11, no. 8 (2002): 1835-2042.

Hausman, Jerry A. "Specification tests in econometrics." Econometrica: Journal of the econometric society (1978): 1251–1271.

Hayashi, Fumio. "Econometrics. Princeton." New Jersey, USA: Princeton University (2000).

Henisz, Witold J. "The political constraint index (POLCON) dataset."

Heyns, Christof H., and Frans Viljoen, eds. The impact of the United Nations human rights treaties on the domestic level. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2002.

Hill Jr, Daniel W. "Estimating the effects of human rights treaties on state behavior." The Journal of Politics 72, no. 4 (2010): 1161–1174.

Hillebrecht, Courtney. “The Domestic Mechanisms of Compliance with International Human Rights Law: Case Studies from the Inter-American Human Rights System.” Human Rights Quarterly 34, No. 4 (2012): 959-985.

Hendrix, Cullen S. "Measuring state capacity: Theoretical and empirical implications for the study of civil conflict." Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 3 (2010): 273-285.

Hendrix, Cullen S., and Joseph K. Young. "State Capacity and Terrorism: A Two Dimensional Approach." Security Studies 23, no. 2 (2014): 329-363.

Huneeus, Alexandra. "Courts resisting courts: Lessons from the Inter-American Court's Struggle to Enforce Human Rights." Cornell International Law Journal 44, no. 3 (2011): 102-155.

Jacob, Daniel, Bernd Ladwig and Andreas Oldenbourg. "Human Rights Obligations of Non-State Actors in Areas of Limited Statehood." SFB-Governance Working Paper Series. No 27 (2012).

Jetschke, Anja. Human Rights and State Security: Indonesia and the Philippines, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

Keck, Margaret E., and Kathryn Sikkink. Activist Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998.

Keele, Luke, and Nathan J. Kelly. "Dynamic models for dynamic theories: The ins and outs of lagged dependent variables." Political Analysis 14.2 (2006): 186-205.

Keith, Linda Camp. "The United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights: Does it make a difference in human rights behavior?." Journal of Peace Research 36, no. 1 (1999): 95-118.

Krasner, Stephen, and Thomas Risse. "External Actors, State Building and Service Provision in Areas of Limited Statehood: Introduction." Governance 27, no. 4 (2014): 545-576.

Landman, Todd. Protecting Human Rights: A Comparative Study. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2005.

Lupu, Yonatan. "Legislative veto players and the effects of international human rights agreements." American Journal of Political Science 59, no. 3 (2015): 578-594.

Melander, Erik, Therése Pettersson, and Lotta Themnér. "Organized violence, 1989–2015." Journal of Peace Research53, no. 5 (2016): 727–742.

Moravscik, Andrew. "Integrating Domestic and International Theories of International Bargaining." Double-Edged Diplomacy: International Bargaining and Domestic Politics (1997): 12.

Muñoz, Alejandro Anaya. "Transnational and domestic processes in the definition of human rights policies in Mexico." Human Rights Quarterly 31 (2009): 35.

Murdie, Anamda M and David R. Davis “Shaming and Blaming: Using Events Data to Assess the Impact of Human Rights INGOs”, International Studies Quarterly, 56 (2012): 1–16.

Moravcsik, Andrew. "The origins of human rights regimes: Democratic delegation in postwar Europe." International Organization (2000): 217–252.

Neumayer, Erik. "Do international human rights treaties improve respect for human rights?" Journal of Conflict Resolution 49, no. 9 (2005): 925-953.

Nickell, Stephen. "Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects." Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society (1981): 1417–1426.

Payne, Caroline L. and M. Rodwan Abouharb. “The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the strategic shift to forced disappearance”, Journal of Human Rights, 15 (2016), no. 2, pp. 1–26.

Post, Lori Ann, Amber N. W. Raile and Eric D. Rile. “Defining Political Will.” Politics and Policy 38, no. 4 (2010): 653–676.

Powell, Emilia Justyna, and Jeffrey K. Staton. "Domestic judicial institutions and human rights treaty violation." International Studies Quarterly 53, no. 1 (2009): 149–174.

PRS Group and others. (2018). International country risk guide. Political Risk Services.

Rejali, Darius. Torture and Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Richards, David L., and Ronald D. Gelleny. "Good things to those who wait? National elections and government respect for human rights." Journal of Peace Research 44, no. 4 (2007): 505-523.

Risse, Thomas and Kathryn Sikkink. "Conclusions." Risse, Thomas, Stephen C. Ropp and Kathryn Sikkink. The Persistent Power of Human Rights: From Commitment to Compliance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013. 275–295.

Risse, Thomas, and Stephen C. Ropp. "Introduction and overview." Risse, Thomas, Stephen C. Ropp and Kathryn Sikkink. The Persistent Power of Human Rights: From Commitment to Compliance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013. 3–25.

Risse, Thomas, Stephen C. Ropp, and Kathryn Sikkink. The Power of Human Rights: International Norms and Domestic Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Ron, James. "Varying methods of state violence." International Organization 51, no. 2 (1997): 275-300.

Schimmelfennig. “The Community Trap: Liberal Norms, Rhetorical Action, and the Eastern Enlargement of the European Union”. International Organizacion 55, no. 1 (2001): 47–80.

Shor, Eran. "Conflict, Terrorism, and the Socialization of Human Rights Norms: The Spiral Model Revisited." Sociological Perspectives 51, no. 4, (2008): 803–826.

Sikkink, Kathryn. "Human rights, principled issue networks, and sovereignty in Latin America." International Organization 47, no. 3, (1993): 411–441.

Simmons, Beth A. Mobilizing for human rights: international law in domestic politics. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Smith-Cannoy, Heather. Insincere commitments: Human rights treaties, abusive states, and citizen activism. Georgetown University Press, 2012.

Teorell, Jan, Stefan Dahlberg, Sören Holmberg, Bo Rothstein, Anna Khomenko, and Richard Svensson. 2017. The Quality of Government Standard Dataset, version Jan17. University of Gothenburg: The Quality of Government Institute, http://www.qog.pol.gu.sehttps://doi.org/10.18157/QoGStdJan17

Voeten, Erik. “Domestic implementation of European Court of Human Rights Judgments: Legal Infrastructure and Government Effectiveness Matter: A Reply to Dia Anagnostou and Alina Mungiu-Pippidi.” The European Journal of International Law 24, no. 1 (2014): 229-238.

Wood, Reed M., and Mark Gibney. "The Political Terror Scale (PTS): A re-introduction and a comparison to CIRI." Human Rights Quarterly 32, no. 2 (2010): 367-400.

Wooldridge, J. M. "Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, (Boston: Cengage Learning)." (2012).

Wooldridge, Jeff. 2014. https://www.statalist.org/forums/forum/general-stata-discussion/general/18775-iv-regression-with-continuous-interaction-term

World Bank. World development indicators 2018.

Wu, De-Min. "Alternative tests of independence between stochastic regressors and disturbances: Finite sample results." Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society (1974): 529–546.

Zhou, Min. "Participation in international human rights NGOs: The effect of democracy and state capacity." Social Science Research 41 (2012): 1254-1274.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anaya-Muñoz, A., Murdie, A. The Will and the Way: How State Capacity and Willingness Jointly Affect Human Rights Improvement. Hum Rights Rev 23, 127–154 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12142-021-00636-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12142-021-00636-y