Abstract

Modified activated carbon sorbents (ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe) had been prepared from the activation of corn husks precursor to increase the chemical activity of the resulting adsorbents by increasing the number of active functional groups and generation of micro-mesoporous structures. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) assessed the acidic surface properties of the prepared activated carbons that is due to the presence acidic functional groups such as –OH and –COOH which improves the removal efficiency of the produced sorbents. Textural characteristics revealed the generation of micro-mesoporous structures in ACP–Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe. Thus the combination of H3PO4 with Zn or Zn–Fe could enhance the mesoporosity with a considerable decrease in the adsorption of nitrogen. However, the formation of mesopores might be attributed to the template-like effects of the obtained Zn- of Zn-Fe compounds inside the carbon structure. These structures were employed as sorbents for removal of hexavalent chromium Cr(VI) ions from its aqueous solutions, and the removal efficiency reached ~ 86% for ACP-Zn-Fe and ~ 82% for ACP-Zn. The kinetic modeling studies revealed that the sorption process follows the pseudo-second-order model which indicates that the mechanism of process is chemisorptions. Freundlich, Langmuir and Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R) models were used to express the experimental data. The isotherm modeling studies revealed that the sorption process was fit with both Freundlich and Langmuir models with maximum capacity 24.8 and 30.3 mg/g for ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The environmental difficulties caused by heavy metal ions in water need the development of new efficient methods for removing these contaminants, especially because their accumulation in living creatures at extremely low concentrations causes significant health problems (Monier et al. 2010; Essawy and Ibrahim 2004; Xiao et al. 2017). Because of the difficulties in properly removing these pollutants from water, continuous attempts are made in this situation (Futalan et al. 2012; Baraka and Heslop 2007). Accordingly, several studies were allocated to evolve suitable sorbents for this purpose which would be featured by high capacity and selectivity to a number of metal ions (Yildiz et al. 2010; Kirupha et al. 2013; Saravanan and Ravikumar 2015a; Ahmad et al. 2018).

Although chromium is an essential element for plant and animal metabolism, its accumulation in the environment as a result of industrial outputs may have negative impacts on human health (Fan et al. 2019). Many industrial processes such as dyes and pigment manufacturing, wood preserving, electroplating and leather tanning operations are responsible for discharging wastewater contaminated by chromium (Fan et al. 2019; Demiral et al. 2008; Kumar and Jena 2017a, 2017b; Yang et al. 2015; Ukanwa et al. 2019; Heidarinejad et al. 2020). The main oxidation states of Cr ions are +3 and +6 where the other oxidation states are not stable in aqueous media. Cr (VI) ions are more harmful and present in the forms of chromate (CrO42−) and dichromate (Cr2O72−). Conventional methods such as reduction followed by precipitation, solvent extraction, reverse osmosis, ion exchange and electrolytic methods have been applied for removing Cr(VI) ions from industrial wastewater. However, these methods have found limited in the application because they often involve high capital and operational costs. On the contrary, adsorption process is an effective and versatile method for removing chromium ions (Fan et al. 2019; Demiral et al. 2008; Kumar and Jena 2017a, 2017b; Yang et al. 2015). Particularly, adsorption using activated carbon materials derived from agricultural wastes is found to be effective and eco-friendly process as compared to the other methods (Demiral et al. 2008; Kumar and Jena 2017a, 2017b; Yang et al. 2015). The obtained AC samples used in these studies have been prepared using steam activation (Demiral et al. 2008), ZnCl2 activation (Kumar and Jena 2017a), H3PO4 activation (Kumar and Jena 2017b) and NaOH activation (Yang et al. 2015). As well known, two general preparation schemes are currently used in preparation of ACs from agricultural wastes (Ukanwa et al. 2019; Heidarinejad et al. 2020). The first scheme is the physical activation and involves the pyrolysis of carbonaceous raw during flow of oxidizing gases such as air, steam and CO2. The second is the chemical activation scheme and involves only one thermal treatment stage for carbonaceous raw with different activating agents which have been reported in the literature, such as ZnCl2, FeCl3, H3PO4, NaOH, or KOH and others (Ukanwa et al. 2019; Heidarinejad et al. 2020; Sych et al. 2012; Kilic et al. 2012). Among these, the activation with H3PO4 offers many recommended advantages; it is performed in one pyrolysis step at a much lower temperature (400–600 °C), which leads to a much higher carbon yield (35–50 %), and most of the impregnate can be recovered by multistage extraction (Sych et al. 2012). Accordingly, a large number of feedstocks of biomass have been extensively exploited based on their prevalence in the considered region of the world (e.g., bagasse, wood trees, fruit stones, nutshells, water hyacinth, coffee beans, cotton stalks, olive stones and many others) (Ukanwa et al. 2019; Heidarinejad et al. 2020). In the present investigation, the developed activated carbons were prepared from corn husks by impregnation with 50 % H3PO4 followed by thermal treatment at 700 °C for 2 h, under its own atmosphere, or followed by mixing with either zinc chloride or zinc chloride/ferric chloride mixture and then carbonized at the same temperature. The combination of two or three chemical reagents through preparation of ACs is reported here for the first time. The surface and porosity characteristics were evaluated by FTIR, XRD and N2 adsorption at 77 K. Testing of the adsorption capacity from solution was carried out by determining the adsorption isotherms of Cr(VI) cations. It was intended to assess the impact of chemical activation schemes on the adsorption characteristics of ACs obtained.

Experimental

Preparation of activated carbons

Corn husks (CHs)were washed several times with distilled water to remove any impurities then cut into small pieces and dried at 80 °C for 24 h followed by crushing and sieving (0.5–3.0 mm).

Three schemes of chemical activation route including phosphoric acid, phosphoric acid–zinc chloride and phosphoric acid–zinc chloride–ferric chloride were activated CHs powder as carbonaceous precursor to produce activated carbon adsorbents. This precursor of activated carbons was local and discarded from food processing industry. CHs were first washed with hot water to be free from dirt and then dried at 80 °C overnight. The dried species were cut and ground in a laboratory mill to a grain size from 0.5 to 3.0 mm. The resultant powder was impregnated using a 100 ml solution of 50% H3PO4 (Rasayan, a concentration of 85%) and left overnight to achieve good soaking, then separated from the remaining H3PO4 solution and transferred to an oven at 80 °C to be dried overnight. The sample was divided into two portions to prepare activated carbons. In the first step, a portion was transferred to stainless steel reactor (length of 60 cm and inner diameter of 40 mm and closed at one end) and heated slowly to 500 °C within 1 h, and then reach to final temperature of 700 °C and hold for 2 h. After heating stop, the carbonized material was thoroughly washed by boiling in 500 ml aliquots of water, decanted and rewashed several times until washings filtrate reached pH ≥ 5.5, finally filtered and dried overnight at 110 °C and denoted as ACP.

The second portion of impregnated sample was treated with zinc chloride (PubChem, assay 98%, 163.3 g/mol) at mass ratio of sample/salt = 5:1 and dried at 80 °C overnight. Then, the dried sample was carbonized in the same furnace and at the same temperature for 2 h. The carbonized product was washed, filtered, dried at 110 °C and labeled as ACP-Zn. In the third route, H3PO4-ZnCl2-FeCl3 activation pathway was carried out. A portion of powdered corn husks which soaked firstly with chemical agents of H3PO4 and ZnCl2 was treated with ferric chloride hexahydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, assay 98%, 270.3 g/mol) and then dried at 80 °C overnight. After that, the dried sample was carbonized as mentioned above under the same conditions. The produced activated carbon was labeled as ACP-Zn-Fe.

Sample characterizations

The essential surface functional groups formed on the surface of the prepared samples were determined by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, using KBr pellets (JASCO, FTIR-460 plus).

The textural parameters such as Brunauer–Emmett–Teller surface area (SBET, m2/g), total pore volume (VP, cm3/g) and average pore diameter (\(\overline{r}\), Å) (Sych et al. 2012) were determined using nitrogen adsorption analysis (BEL-Sorp, Microtrac Bel Crop, Japan) at ‒196 °C and P/P0 = 0.005–0.999. Before N2 adsorption analysis, samples (0.1–0.2 g) were subjected to a vacuum of 10−5 Torr at 250 °C for 12 h in the degassing chamber.

The crystal phase compositions of the obtained catalysts were defined using X-ray diffraction technique by using a Bruker diffractometer (Bruker D8 advance, Germany) with CuKα1 (λ = 0.15418 nm) at room temperature. The accelerating voltage of 40 kV, emission current of 40 mA and scanning speed of 4°/min were used.

Adsorption studies

Stock solution of Cr(VI) was prepared in deionized water from potassium dichromate (K2CrO4.5H2O) (Merck). A comparative study was carrying out to assess the uptake capacities of ACP, ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fefor hexavalent chromium. 0.5 g/L of ACP,ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe was shaking with a synthetic solution of Cr(VI) (12 mg/L)in a mechanical shaker at 150 rpm for 3 h at pH value of 2.5 ± 0.1.

Hexavalent chromium uptake capacities (Qt, mg/g) were calculated using the following equation:

where C0 (mg/L) is the initial concentration of hexavalent chromium, Cf (mg/L) is the equilibrium concentration of Cr(VI) in aqueous solution, V (L) is the volume of solution, M (g) is the mass of the adsorbent and Qt (mg/g) is the calculated Cr(VI) adsorption amount onto ACP,ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe.

The optimum removal of Cr (VI) by ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe, isotherm and kinetic models were studied through batch adsorption method. Therefore, the effects of different parameters on the sorption of chromium ions, such as pH(from 2 to 8), contact time (from 15 to 300 min.), sorbent dosage (from 0.25 to 2.0 g/L) and initial ions concentration (from 5 to 30 mg/L), were investigated using mechanical shaker at 150 rpm. After filtration using Whatman® (No. 41) filter papers, concentration chromium ions were measured in the samples. All experiments were repeated three times, and the percentage of chromium ions removal by ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe during a series of batch investigations can be expressed using Eq. (2):

The initial and final chromium ions concentrations in solution are Co and Cf (mg/L), respectively. Chromium ions concentration was determined for the samples using inductive coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (Agilent ICP-OES 5100, Australia) in accordance with standard methods for water and wastewater analysis (Rice et al. 2017).For the triplicate, the relative standard deviation is < 1%.

Results and discussion

Surface functional groups

Three obtained samples were analyzed by FTIR, which are: the activated carbon impregnated with 50% H3PO4 and heated at 700 °C (ACP), activated carbon impregnated with 50% H3PO4/ZnCl2 and heated at 700 °C (ACP-Zn) and its counterpart of the activated carbon impregnated with 50% H3PO4/ZnCl2/FeCl3 and pyrolyzed at 700 °C (ACP-Zn-Fe). Their recorded FTIR spectra are shown in Fig. 1, and their absorption bands can be divided into four regions: 4000–2000, 2000–1300, 1300–900 and 900–600 cm−1. The first region is usually assigned to groups of mostly free O–H, H–bonded O–H, adsorbed H2O and aliphatic units of symmetric and asymmetric stretching in CH–, CH2–, or CH3– bonds, respectively. The second range (2000–1300 cm−1) is ascribed to the most important oxygen functionalities characterized by the presence of C = O and N–O containing structures in carbonyls, lactones, aldehydes and carboxylic radicals. A broad and strong absorption band in the third range, which appears between 1300 and 900 cm−1, is mainly owing to stretching of C–O single bonds in ethers, esters, phenols and hydroxyl groups. Moreover, shoulder bands at lower wave numbers (830, 760, 670 and 600 cm−1) are associated with out-of-plane bending modes of C–H as in benzene derivatives (Sych et al. 2012; Kilic et al. 2012). Observed shoulders in the 1460–1180 cm−1 range are ascribed to phosphorus species; e.g., P = O, P–O–C and P = OOH, and organic P–compounds (Sych et al. 2012). Two characteristic absorption bands at 1730 and 1630 cm−1 were observed in FTIR spectra of ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe samples which are attributed to stretching vibration modes of both C = O and O–H groups in the carboxylic acids. As a result of a combination of Zn– or Zn–Fe bimetallic activation with H3PO4, the acidity character of activated carbon surface increased. In addition, the weak absorption bands/or shoulders at 800–600 cm−1 are usually associated with the residual presence of aliphatic stretching and particularly the out-of-plane deformation mode of C–H in the substituted benzene rings. Moreover, the bands at 560 and 445 cm−1 were associated with the Zn–O and Fe–O vibrations bonds (Tian et al. 2019; Guo et al. 2019). In sum, the strong acidity in the prepared activated carbons is owing to carboxylic or acidic functional groups; rather it should be associated with organic/inorganic phosphorus compounds. This behavior would increase the removal of Cr(VI) ions using the prepared ACs from corn husks.

Upon adsorption Cr(VI) ions onto ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe samples, FTIR spectra are recorded also and exhibited considerable changes in the stretching vibration modes of functional groups such as O–H, C = O, C–O and phosphorous groups (Fig. 1). Some of these functional groups are disappeared (like bands of OH groups) while others showed a decrease in its transmittance intensity. These findings indicated that the prepared AC samples by co-activation have a high affinity toward Cr(VI) ions adsorption through formation intermolecular bonds with these groups (Rai et al. 2016). Therefore, the adsorption of Cr(VI) ions on the surfaces of ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe samples is feasible.

Textural and crystalline characteristic

Figure 2a shows the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of ACP, ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe samples. It can be seen that ACP sample exhibited type I of adsorption isotherm. This finding indicates that ACP is mainly microporous sample. When activation is carried out using H3PO4 combined with Zn or Zn-Fe, the type of adsorption isotherms became a combination between I and IV. This is corresponded to generation of micro-mesoporous structures in ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe. Therefore, the combination of H3PO4 with Zn or Zn-Fe enhanced the mesoporosity with a considerable decrease in the uptake of nitrogen. And as illustrated in Fig. 2b, the pore size distributions of samples were different and uniform and the maximum peaks were observed at 1.12, 2.30 and 4.08 nm for ACP, ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe. This result affirmed that the presence of Zn or Zn-Fe salts within activation of corn husks with H3PO4 could enhance significantly the formation of mesopores. Table 1 summarizes the total specific surface areas and total pore volumes of the samples. The recorded total specific surface areas manifest that ACP had the highest surface area (474 m2/g) and lowest mesoporosity (22.6%). The addition of Zn– or Zn–Fe decreased the total specific surface area. This may be due to the damage of some pore or blocking pores However, the formation of mesopores might be attributed to the template-like effects of the obtained Zn– of Zn–Fe compounds inside the carbon structure (Xu et al. 2020). Some studies employed mixtures of iron chloride with other activating agents, even including an activating step in the presence of a gasification agent. In this sense, Tian et al. (Tian et al. 2019) also prepared activated carbon by activation of waste cotton with FeCl3/ZnCl2 mixture. According to this study, the pore development process is due to the creation of molten ZnCl2 and Fe species, which act as templates to create porosity, and the dehydration effect of ZnCl2 and FeCl3 on the carbonaceous cotton waste precursor. Guo et al. (Guo et al. 2019) found that FeCl3 and ZnCl2 are responsible for microporosity development.

To explore the crystalline phases obtained in the carbon structure, XRD patterns of ACP (highest total specific surface area) and ACP-Zn-Fe (lowest total specific surface area) are shown in Fig. 3. XRD pattern of ACP showed the peaks of graphite lattice at 2θ 29.5° (110) and 42.2° (200) with phosphates (P) at 2θ 35.5° (111) (Kilic et al. 2012; Rice et al. 2017). For further activation in the presence of Zn and Fe cations, several peaks were determined that related to formation of Fe2O3 and ZnO into surface of activated carbons obtained (Fig. 3). It can be deduced also that there was no reaction between FeCl3 and ZnCl2 during the activation process (Tian et al. 2019; Guo et al. 2019).

Studying the ability of ACP, ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe for adsorption of hexavalent chromium ions

From studying the ability of 0.5 g/L for each of ACP,ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe for adsorbing of 12 mg/l of Cr(VI) at pH 2.5 for 3 h, it was found that Cr(VI) ions uptake capacities were 3, 17.7 and 19.54 mg/g, respectively. This means that the uptake capacity of Cr(VI) ions for ACP-Zn-Fe and ACP-Zn was more efficient than ACP due to the presence of Zn or Zn–Fe salts within activation of corn husks with H3PO4 that could enhance significantly the formation of mesopores as shown in Table 1. Therefore, study is carrying out for ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe.

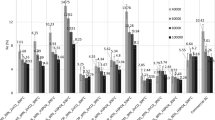

Effect of pH on removal efficiency of hexavalent chromium ions by ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe

The pH influence on removal efficiency of hexavalent chromium ions from its aqueous solutions by using ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe was investigated in the pH range from 2.0–8.0 at initial concentration of 12 mg/L. Figure 4 represents the efficiency of hexavalent chromium ions removal; it is decreased with raising the pH from 2.0 (54.16%) to 8.0 (16.67%) for ACP-Zn-Fe and from 2.0 (53.3%) to 8.0 (7.5%) for ACP-Zn. Thus, the pH range 2.0–2.5 is maintaining for all the following experiments of this study.

Effect of contact time

Equilibrium time is essential to study the time required for adsorption process (Maksin et al.2012).Figure 5 illustrates the removal of Cr(VI) by ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe. For ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn, the removal efficiency reached to 31.7% and 38.9% within 15 min, respectively. By increasing the contact time to 240 min., the removal efficiency is reached to 70.8% and 80%, respectively.

Effect of adsorbents dose

Sorbent surface area and accessibility of active sites play an important role for its removal efficiency, and it is a function of the sorbent dose (Saravanan and Ravikumar 2015b).

Figure 6 demonstrates the removal behavior of the Cr(VI) as a function of ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe sorbents doses, which ranged from 0.25 to 2 g/L. The equilibrium dose was attained at 1 g/L for both ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe, and there was a slight increase in the removal efficiency of Cr(VI) by increasing the sorbent dose. This means that there is accessibility of active sites for adsorption of Cr(VI) on the surface of sorbent.

Effect of initial Cr(VI) concentration on the removal efficiency the adsorbents

Different concentrations of Cr(VI)(5–30 mg/L) were employed at the optimum operating conditions of pH values (2–2.5), contact time (240 min) and sorbent dose (1 g/L) as demonstrated in Tables 2, 3. It is clear that by increasing the concentration of Cr(IV), the uptake capacity of both ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe was increased, while the removal percent of Cr(VI) decreased from 82 to 62% for ACP-Zn and from 86 to 70.5 for ACP-Zn-Fe.

Kinetic modeling

Applying of kinetic modeling (Lagergren pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order) is important for predicting the dynamics of the sorption process and designing of sorption system (Ho 2006; Plazinski et al. 2009). The model that fulfillment between the theoretical and experimental data with higher correlation coefficient will be used for explanation of the sorption process.

Pseudo-first-order kinetic model

The integral form of sorption rate and capacity would be expressed by the pseudo-first-order (Lagergren 1898) kinetic model (Eq. 3):

where k1(min−1)is the constant of first-order sorption (Lagergren rate constant), qe is the quantity of hexavalent chromium ions up taken on the sorbent at the equilibrium (meq/g) and qt(t, min)is the amount of chromium ions adsorbed on the sorbent at a time. From the slope and intercept of Fig. 7a and b,k1 and qe can be calculated.

The Lagergren pseudo-first order is a hypothesis model that is the direct relation for removal rate of hexavalent chromium ions to the number of free sorbent active sites.

The first-order model has not a realistic estimation of qe for uptake of hexavalent chromium ions where the experimental value of qe (1.962 and 2.5 meq/g) is not fitted the calculated value (1.086 and1.3335 meq/g) for ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe, respectively. Here the amount of binding sites (qe) at zero intercept are linked by the rapid uptake of the hexavalent chromium ions by ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe, which is lesser than the equilibrium uptake that gives misestimating this value. Table 4 shows that the correlation coefficient (R2) is < 0.95 for both ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe which also confirm the denial for the description of first-order reaction for the uptake of Cr (VI) ions onto ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe.

Pseudo-second-order model

Hexavalent chromium ions up taken is proportional to square of the sorbent unoccupied sites number according to presume of the pseudo-second-order model Eq. (4) (Ho et al. 2000).

where k2 is the reaction rate constant and Eq. (4) represents the second-order linearized plot of t/qt against t (Fig. 8a and b). From the y-intercept of the plot, k2 value was obtained (0.0159 and 0.0098); from the slope (2.168 and 2.5 meq/g) qe was obtained which are nearby to the experimental values (1.962 and 2.2 meq/g) for ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe, respectively. The data from Table 4 confirm that the chemisorption reaction follows the pseudo-second-order model with correlation coefficients > 0.97 for both ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe (Abramian and El-Rassy 2009). In general, the chemisorption reaction is done by a covalent forces and/or ion exchange of electrons with the hexavalent chromium ions and ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe (Ho and McKay 1998).

Isotherm models

The sorption route of hexavalent chromium ions in the presence for both ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe sorbents is examined using Langmuir, Freundlich and Dubinin–Kaganer–Radushkevich (DKR) isotherm models to optimize the parameters of system design treatment (Mittal et al. 2015).

A linear simplified Eq. (5) for Langmuir isotherm model is presume a monolayer sorption of hexavalent chromium ions onto a surface for both ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe with a finite number of identical sites (Langmuir 1916).

where Ce is the equilibrium concentration of Cr(IV) in solution (mg/L), qe is the adsorbed quantity at equilibrium onto ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe(mg/g), K is Langmuir constant relating to enthalpy of the sorption process and qmax is the maximum sorption capacity of chromium ions per unit mass of the sorbent when all binding sites are occupied (saturation).

Equation (6) is presume a simplified form of Freundlich isotherm model

where kf and n are constants, corresponding to the sorption capacity and intensity parameters of chromium sorption onto both samples (ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe), respectively. Equilibrium data were obtained from the main isotherm models (Schiewer and Volesky 2000; Saygideger et al. 2005). The isotherm parameters of both models are represented in Table 4. Values of R2 were 0.9048 and 0.9243 for ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe, respectively, for Langmuir model, which reveal that monolayer sorption process of hexavalent chromium ions onto a surface of both ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe may be occurred.

Moreover, the heterogeneous sorption reaction interpreted by Freundlich isotherm model (Freundlich 1906). The implementation of Freundlich isotherm gives R2of 0.95 and 0.98 for ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe, respectively, which confirm the strength of Freundlich isotherm model for sorption process. The result of Langmuir model gives the maximum sorption capacity (qmax) of 24.8 and 30.3 mg Cr(IV)/g using ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe(Figs. 9a, b and 10a,b), respectively. Table 5 shows that 1/n is 0.54 and 0.59 for the adsorption process on the ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe, respectively, which concluded that the sorption process can be significantly remove chromium ions from aqueous solutions and efficiently occurs at low concentration as 0.1 < 1/n < 1.0 (Guo et al. 2017; Ayawei et al. 2015).

Dubinin–Kaganer–Radushkevich (DKR) model

DKR model is a broad model as it is not assuming a constant sorption potential or homogeneous surface (Naima et al. 2013). Equation (7) simplifies the linear equation of DKR isotherm:

where Xm (mol/g) is the maximum quantity of chromium ions that may be adsorbed onto a gram unit of the ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe, β (mol2/J2)is a constant to the sorption energy and ε is the Polanyi potential that can be calculated by using the following equation:

where R (8.314 J/mol K) is the gas constant and T (T = 298 Kelvin) is the absolute temperature (Foo and Hameed 2010; Dubinin et al. 1947). Figure 11a, b represents the relationship between lnqe against to ε2, and thus, the slope was the sorption capacity (Xm) (− 0.2544 × 10–8 mol2/J2) of the (ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe), respectively. The free energy of sorption is acquainted as the free energy change when one mole of chromium ions is transferred from the solution infinity to the surface of ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe. Accordingly, the sorption energy can be calculated by the following Eq. (9):

Table 5 and Fig. 11a, b show the sorption free energy (E) of ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe for chromium ions removal which was around ≈10 kJ/mol. The endothermic reaction confirmed by the positive free energy. The E value (10 kJ/mol) that ranged between 8 and 16 kJ/mol means that the sorption process onto ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe is chemical in nature (Samadi et al. 2015) as confirmed before by the pseudo-second-order model.

Conclusions

Activated carbon sorbents had been prepared from the activation of corn husks (CHs) powder as carbonaceous precursor by using three schemes of chemical activation route including phosphoric acid, phosphoric acid–zinc chloride and phosphoric acid–zinc chloride–ferric chloride. The presence of phosphoric acid–zinc chloride–ferric chloride increases the chemical activity of the resulting adsorbents by increasing the number of active functional groups and by generation of micro-mesoporous structures. The significant removal efficiency of Cr(VI) ions was achieved using micro-mesoporous sorbents which reached to 82% for ACP-Zn and 86% for ACP-Zn-Fe under optimized conditions. The free energy for Cr+6 ions removal reaction by ACP-Zn and ACP-Zn-Fe is endothermic reached to ≈10 kJ/mol.

References

Abramian L, El-Rassy H (2009) Adsorption kinetics and thermodynamics of azo-dye orange II onto highly porous titania aerogel. Chem Eng J 150:403–410

Ahmad Z, Gao B, Mosa A, Yu HW, Yin XQ, Bashir A, Ghoveisi H, Wang SS (2018) Removal of Cu(II), Cd(II) and Pb(II) ions from aqueous solutions by biochars derived from potassium-rich biomass. J Clean Prod 180:437–449

Ayawei N, Ekubo AT, Wankasi D, Dikio ED (2015) Mg/Fe layered double hydroxide for removal of lead (II): Thermodynamic, equilibrium and kinetic studies. Eur J Sci Eng 3:1–17

Baraka A, Heslop PJ (2007) Preparation and characterization of melamine-formaldehyde DTPA chelating resin and its use as an adsorbent for heavy metals removal from wastewater. React Funct Polym 67:585–600

Demiral H, Demiral I, Tümsek F, Karabacakoğlu B (2008) Adsorption of chromium (VI) from aqueous solution by activated carbon derived from olive bagasse and applicability of different adsorption models. Chem Eng J 144:188–196

Dubinin MM, Zaverina ED, Radushkevich LV (1947) Sorption and structure of active carbons. I. Adsorption of organic vapors. Zh Fiz Khim 21:1351–1362

Essawy H, Ibrahim H (2004) Synthesis and characterization of poly (vinylpyrrolidone-co-methylacrylate) hydrogel for removal and recovery of heavy metal ions from wastewater. React Funct Polym 61:421–432

Fan Z, Zhang Q, Gao B, Li M, Liu C, Qiu Y (2019) Removal of hexavalent chromium by biochar supported nZVI composite: batch and fixed-bed column evaluations, mechanisms, and secondary contamination prevention. Chemosphere 217:85–94

Foo KY, Hameed BH (2010) Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem Eng J 156:2–10

Freundlich HMF (1906) Over the adsorption in solution. J Phys Chem 57:385–470

Futalan C, Tsai W, Lin S, Hsien K, Dalida M, Wan M (2012) Copper, nickel and lead adsorption from aqueous solution using chitosan-immobilized on bentonite in a ternary system. Sust Environ Res 22:345–355

Guo Z, Zhang J, Liu H, Kang Y (2017) Development of a nitrogen-functionalizedcarbon adsorbent derived from biomass waste by diammonium hydrogen phosphateactivation for Cr (VI) removal. Powder Technol 318:459–464

Guo F, Jiang X, Jia X, Liang S, Qian L, Rao Z (2019) Synthesis of biomass carbon electrode materials by bimetallic activation for the application in supercapacitors. J Electroanal Chem 844:105–115

Heidarinejad Z, Dehghani MH, Heidari M, Javedan G, Ali I, Sillanpää M (2020) Methods for preparation and activation of activated carbon: a review. Environ Chem Lett 18:393–415

Ho YS (2006) Review of second-order models for adsorption systems. J Hazard Mater 136:681–689

Ho YS, McKay G (1998) A comparison of chemisorption kinetic models applied to pollutant removal on various sorbents. Proc. Saf. Environ. Prot. (Trans IChem. E., Part B) 76:332–340

Ho YS, Mckay G, Wase DJ, Foster CF (2000) Study of the sorption of divalent metalions onto peat. Adv Sci Technol 18:639–650

Kilic M, Apaydin-Varol E, Pütün AE (2012) Preparation and surface characterization of activated carbons from Euphorbiarigida by chemical activation with ZnCl2, K2CO3, NaOH and H3PO4. Appl Surf Sci 261:247–254

Kirupha S, Murugesan A, Vidhyadevi T, Baskaralingam P, Sivanesan S, Ravikumar L (2013) Novel polymeric adsorbents bearing amide, pyridyl, azomethine and thiourea binding sites for the removal of Cu (II) and Pd (II) ions from aqueous solution. Sep Sci Technol 48:254–262

Kumar A, Jena HM (2017a) Adsorption of Cr(VI) from aqueous phase by high surface area activated carbon prepared by chemical activation with ZnCl2. Process Safe Environ Protect 109:63–71

Kumar A, Jena HM (2017b) Adsorption of Cr(VI) from aqueous solution by prepared high surface area activated carbon from Fox nutshell by chemical activation with H3PO4. J Environ Chem Eng 5:2032–2041

Lagergren S (1898) Zur theorie der sogenannten adsorption geloster stoffe. Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens, Handlingar 24:1–39

Langmuir I (1916) The constitution and fundamental properties of solids and liquids. J Am Chem Soc 38:2221–2295

Maksin DD, Kljajević SO, Đolić MB, Marković JP, Ekmeščić BM, Onjia AE, Nastasović AB (2012) Kinetic modeling of heavy metal sorption by vinyl pyridine based copolymer. Hem Ind 66:795–804

Mittal H, Maity A, Ray SS (2015) The adsorption of Pb2+ and Cu2+ onto gum ghatti-grafted poly(acrylamide-co-acrylonitrile) biodegradable hydrogel: Isotherms and kinetic models. J Phys Chem B 119:2026–2039

Monier M, Ayad D, Wei Y, Sarhan A (2010) Adsorption of Cu(II), Co(II), and Ni(II) ions by modified magnetic chitosan chelating resin. J Hazard Mater 177:962–970

Naima A, Mohamed B, Hassiba M, Zahra S (2013) Adsorption of lead from aqueous solution onto untreated orange barks. Chem Eng Trans 32:55–60

Plazinski W, Rudzinski W, Plazinska A (2009) Theoretical models of sorption kinetics including a surface reaction mechanism: a review. Adv Colloid Inter Sci 152:2–13

Rai MK, Shahi G, Meena V, Meena R, Chakraborty S, Singh RS, Rai BN (2016) Removal of hexavalent chromium Cr (VI) using activated carbon prepared from mango kernel activated with H3PO4. Resour Effic Technol 2:S63–S70

Rice EW, Baird RB, Eaton AD (2017) Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 23rd Edition, American public health association, american water works association, Water Environment Federation, ISBN: 9780875532875

Samadi N, Hasanzadeh R, Rasad M (2015) Adsorption isotherms, kinetic, and desorption studies on removal of toxic metal ions from aqueous solutions by polymeric adsorbent. J Appl Polym Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/APP.41642

Saravanan R, Ravikumar L (2015a) The use of new chemically modified cellulose for heavy metal ion adsorption and antimicrobial activities. J Water Res Prot 7:530–545

Saravanan R, Ravikumar L (2015b) The use of new chemically modified cellulose for heavy metal ion adsorption and antimicrobial activities. J Water Res Prot 7:530–545

Saygideger S, Gulnaz O, Istifli ES, Yucel N (2005) Adsorption of Cd(II), Cu(II) and Ni(II) ions by Lemna minor, effect of physicochemical environment. J Hazard Mater 126:96–104

Schiewer S, Volesky B (2000) Environmental microbe–metal interactions. ASM Press, Washington, pp 329–362

Sych NV, Trofymenko SI, Poddubnaya OI, Tsyba MM, Sapsay VI, Klymchuk DO, Puziy AM (2012) Porous structure and surface chemistry of phosphoric acid activated carbon from corncob. Appl Surf Sci 261:75–82

Tian D, Xu Z, Zhang D, Chen W, Cai J, Deng H, Sun Z, Zhou Y (2019) Micro–mesoporous carbon from cotton waste activated by FeCl3/ZnCl2: preparation, optimization, characterization and adsorption of methylene blue and eriochrome black T. J Solid State Chem 269:580–587

Ukanwa KS, Patchigolla K, Sakrabani R, Anthony E, Mandavgane S (2019) A review of chemicals to produce activated carbon from agricultural waste biomass. Sustainability 11(6204):1–35

Xiao R, Wang S, Li R, Wang JJ, Zhang Z (2017) Soil heavy metal contamination and health risks associated with artisanal gold mining in Tongguan, Shaanxi, China. Ecotoxicol Environ Safety 141:17–24

Xu Z, Zhou Y, Sun Z, Zhang D, Huang Y, Gu S, Chen W (2020) Understanding reactions and pore-forming mechanisms between waste cotton woven and FeCl3 during the synthesis of magnetic activated carbon. Chemosphere 241:125120

Yang J, Yu M, Chen W (2015) Adsorption of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solution by activated carbon prepared from longan seed: kinetics, equilibrium and thermodynamics. J Ind Eng Chem 21:414–422

Yildiz U, Kemik O, Hazer B (2010) The removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions by novel pH-sensitive hydrogels. J Hazard Mater 183:521–532

Funding

This work was carried out with technical support of National Research Centre including chemicals and equipments.The author(s) received no specific financial funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed equally in the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ammar, N.S., Fathy, N.A., Ibrahim, H.S. et al. Micro-mesoporous modified activated carbon from corn husks for removal of hexavalent chromium ions. Appl Water Sci 11, 154 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-021-01487-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-021-01487-1