Abstract

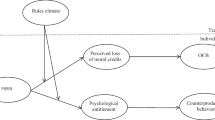

Employee reporting dishonesty is a significant area of concern for firms. In this study, we investigate how providing information about their prosocial actions, such as organizational citizenship behaviors, affects the extent of employee reporting dishonesty. We distinguish prosocial actions whose welfare effects are mutually beneficial (i.e., that help others and the employee), which are common in business practice, from those that are selfless in nature (i.e., that help others at a personal cost to the employee). In addition to examining the effect of the type of prosocial action on the extent of employee reporting dishonesty, we also examine the effect of construal (the manner in which individuals perceive and interpret the action). Using an experiment, we find that participants with high moral identity are less dishonest when they describe their selfless prosocial actions than when they describe their mutually beneficial prosocial actions, but only when they abstractly construe this information. However, we do not find evidence that the reporting dishonesty of participants with low moral identity is influenced by the type of prosocial action they provide information about or the construal of that information. We discuss implications of these results for theory and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data is available from the authors upon request.

Notes

For brevity, hereafter we refer to employee reporting dishonesty simply as employee dishonesty. An alternative way to frame our paper is to characterize employee dishonesty as employee honesty because the level of employee honesty is inversely related to the level of employee dishonesty.

Mutually beneficial prosocial actions are conceptually consistent with the theory of shared value (Ballou et al., 2012; Porter and Kramer 2006, 2011), which pertains to firms’ CSR activities. Specifically, the theory of shared value outlines that CSR activities can be symbiotic, enhancing social welfare while also creating economic benefits for firms. Similarly, CSR activities that employees conceive, design, and execute that benefit both society and the firm (and by extension the employees) fall under the umbrella of mutually beneficial prosocial actions we discuss in our study.

We acknowledge that prior research provides conflicting evidence about the consistency between past prosocial actions on subsequent behavior (Joosten et al., 2014), which provides tension for our H1 prediction. Namely, moral licensing theory predicts ethically inconsistent or compensatory behavior rather than consistent behavior. That is, moral licensing theory posits that past ethical behavior licenses individuals to subsequently behave unethically (Miller and Effron 2010). While some studies provide evidence consistent with a moral licensing effect, the effect has proven difficult to replicate (e.g., Blanken et al., 2014). This may in part be due to the fact that the “moral licensing effect is small to medium in effect size” (Blanken et al., 2015) in contrast to “decades of research in social psychology [that] support the notion that individuals have a strong drive toward consistency (e.g., Beaman et al. 1983, Burger 1999, Festinger 1954, Gawronski and Strack 2012)” (Mullen and Monin 2016). Thus, we rely on moral identity theory to formulate our predictions rather than moral licensing.

Similarly, accounting research documents evidence of consistency in prosocial behavior by firms’ decision-makers. This research reports that firms’ socially responsible behavior is negatively associated with unethical practices such as aggressive earnings management (Kim et al., 2012), insider trading (Gao et al., 2014), and high-profile misconduct (Christensen 2016). In addition, Hoi et al. (2013) find that firms with better CSR performance engage in less aggressive tax avoidance than those with poorer CSR performance.

For brevity throughout the paper, we discuss the accessibility of individuals’ moral and self-interested identities within their working self-concept simply as the accessibility within their self-concept.

Psychological distance is the subjective perception of something’s distance from the self and can vary along dimensions of time, space, social distance, and hypotheticality (Trope and Liberman 2010).

Recent research investigates the accounting implications of CLT and finds that different levels of construal can affect auditors’ professional skepticism and evidence processing (Rasso 2015), employees’ perception of managers’ evaluations (Choi et al., 2016), and how auditors evaluate management’s assumptions (Backof et al., 2018).

Many prior accounting studies have used the mTurk platform (e.g., Bonner et al., 2014; Grenier et al., 2015; Koonce et al., 2015; Rennekamp 2012; Rennekamp et al., 2015). See Mason and Suri (2012) and Rennekamp (2012) for a detailed overview of this subject pool. Studies conducted on mTurk have produced results consistent with those obtained in formal laboratory settings and have reliably replicated prior research that uses alternative experimental methods (see Farrell et al., 2017 and Prickett and Moreton 2014).

We have participants write about a real past personal action rather than using a hypothetical action because a real personal action is more likely to affect the accessibility of each participant’s moral identity and will therefore provide the best test of our theory. This design choice is also consistent with our setting of interest in which employees provide information about a decision for which they feel personally responsible. It is possible that employees also take ownership of the “firm’s actions” that they are not personally involved with. Consistent with this notion, guidelines such as the Security and Exchange Commission’s plain-English Handbook (SEC 1998) encourage employees to write narrative disclosures to stakeholders using first person personal pronouns to describe the firm’s actions. For example, footnote 4 of Lilly’s 2015 sustainability report states, “By reducing our waste, energy, and water use, we’ve saved more than $200 million over the past 7 years.” Likewise, General Electric’s 2014 report states, “We have generated more than $200 billion in revenue from Ecomagination technologies like these and have seen more than $300 million in savings from reduction in our greenhouse gas emissions and water use.”.

Like previous studies (Brown et al., 2009; Evans et al., 2001; Rankin et al., 2008) our setting does not include penalties for misreporting because we are interested in observing reporting behavior when employees have both the incentive and opportunity to misreport. This experimental design choice models any setting in which employees have an information advantage relative to the individuals who use or rely on their reports.

In a post-experimental question, we ask participants the extent to which they believe the reporting task represents an ethical dilemma. Participants respond on an 11-point scale anchored by “Not at all” (1) and “Completely” (11). Consistent with participants viewing the reporting task as an ethical dilemma, we find that the mean response across all manipulated conditions is 7.29, which is significantly higher than the mid-point of the scale (t762 = 11.06, p < 0.001). Including this variable in our analyses does not change any inferences of our hypotheses tests. This suggests that participants perceive the reporting task as an ethical dilemma and that this perception does not affect the differences in dishonesty we observe.

An additional group of mTurk workers was paid in a separate study based on the reporting decisions of the participants in this study.

Twenty-two participants incorrectly identify the true probability of a good outcome and seventeen participants incorrectly answer the question about the effect of their reporting choice on other mTurk workers. The inferences from our hypotheses tests are unchanged if we exclude participants who incorrectly answer the two comprehension check questions from our analyses.

Aquino and Reed’s (2002) moral identity scale consists of two 5-item subscales. The internalization subscale measures how important an individual’s moral identity is to their self-concept. The symbolization subscale measures the extent to which an individual’s actions attempt to display that they are an ethical person. We collect data for both subscales in our study. A confirmatory factor analysis reports two factors consistent with each of these subscales. The theory and predictions of our study are based on the internalization dimension of moral identity, and we do not find evidence that the symbolization dimension has any influence on our results. Therefore, we do not discuss it further, and throughout the paper we refer only to the internalization dimension when we discuss moral identity.

The inferences from our hypotheses tests are unchanged if we do not include age and gender as covariates in our analyses.

Chi-square tests of differences indicate the number of participants removed across each of our experimental conditions is not statistically significant (\(\chi_{2}^{2}\) = 4.08, p = 0.130).

The statistical inferences from our hypotheses tests are unchanged if we use participants’ assessment of how long ago the event they wrote about happened as the construal variable in our statistical models. Further, as an alternative manipulation check, two coders who are blind to our experimental conditions independently rate the construal level of each participant’s submission from the writing task on a 21-point scale, ranging from low construal level (-10) to high construal level (10) (Gamma et al., 2020; Trope and Liberman 2003). The inter-rater agreement is acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.755) and as expected, more abstract ratings are marginally significantly positively correlated with the Distant conditions (p = 0.070).

All reported p-values are two-tailed.

Dummy coding is the simplest method of coding a categorical variable with two or more groups when a researcher wants to compare other groups of the predictor variable with one specific group (the reference group) of the predictor variable (Pedhazur, 1997; Starkweather 2010). Without dummy coding, alternatively treating action type as a categorical variable without a reference group, the interaction terms that include action type would not isolate comparisons between the Selfless and Mutually Beneficial conditions; instead, the interaction terms would be jointly testing comparisons across all three action types. Dummy coding allows us to control for the Selfish condition while testing the interactions of interest. Dummy coding is the most common method for handling categorical independent variables in other general linear models such as OLS and logistic regression (Starkweather 2010). We use the Selfless condition as the reference group so that we can isolate comparisons with the Mutually Beneficial condition while controlling for the Selfish condition. Alternatively, using the Mutually Beneficial condition as the reference group has no impact on the interaction terms that include Selfless vs. Mutually Beneficial as these estimates remain exactly the same.

We verify that our trait measure of Moral Identity is independent of our primary manipulations by testing whether our manipulations have a significant effect on our trait measure. We find that neither our construal manipulation (Recent vs. Distant p = 0.590) nor our prosocial action manipulation (Selfless vs. Mutually Beneficial p = 0.752) have a significant effect on our trait measure, which is consistent with prior research that finds trait Moral Identity is relatively stable (Aquino et al., 2009; Blasi 2004).

To rule out the possibility that our results are driven by mood induced by the type of prosocial action participants write about, we ask participants in a post-experimental question to rate their mood on an 11-point scale anchored by “Extremely bad” (− 5) and “Extremely good” (5) with “Neutral” (0) labeled as the mid-point. When included as a covariate in each of our hypotheses tests, a more positive mood is negatively correlated with misreporting (p < 0.001), but the inferences from our predicted interactions for H2 and H3 are unchanged. Therefore, we conclude that our results are not explained by participants’ mood.

Fairness is believed to be an important behavioral motivator in the economics literature when rewards are divided and shared among individuals (see Camerer 2003). We therefore ask participants about fairness to address this as an alternative explanation for our results, but we do not expect fairness concerns to manifest in our study. That is, when our participants make their reporting decision, they know the payoff they will receive and the payoff a group of other mTurk workers will receive based on their decision; however, participants do not know the number of mTurk workers that will share the group payoff. Thus, our participants are unable to calculate an equitable payoff distribution.

If Fairness and Honesty are included, model fit (\(\chi_{3}^{2}\) = 1.39, p = 0.709) and model results are inferentially identical.

We have no a priori expectation that the link between Wealth Maximization and participants’ level of misreporting should differ between the Selfless and Mutually Beneficial conditions. Therefore, we constrain these link coefficient estimates and find that both are positively associated with participants’ misreporting.

In addition, we test for differences between conditional indirect effects (three-way interaction) using the PROCESS macro Model 11 (Hayes, 2013) and the results are consistent with moderated moderated mediation (90% CI, LLCI = − 25.122, ULCI = − 1.100, untabulated; bias-corrected bootstrap sample based on 5000 samples). Tests of conditional indirect effects indicate Wealth Maximization mediates the relationship between action type and misreporting only when participants have high trait moral identity (90% CI, LLCI = − 27.671, ULCI = − 9.937, untabulated) but not when participants have low trait moral identity (90% CI, LLCI = − 13.707, ULCI = 2.282, untabulated).

We did not disclose to participants the number of stakeholders that would split the stakeholder payoff or how the payoff would be split among stakeholders in order to mitigate any tendency among participants to settle on a “default split” (e.g., 50–50), which would decrease our power to detect differences among conditions.

References

Abbate, C. S., Ruggieri, S., & Boca, S. (2013a). The effect of prosocial priming in the presence of bystanders. The Journal of Social Psychology, 153(5), 619–622.

Abbate, C. S., Ruggieri, S., & Boca, S. (2013b). Automatic influences of priming on prosocial behavior. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 9(3), 479–492.

Aquino, K., Freeman, D., Reed, A., Lim, V. K. G., & Felps, W. (2009). Testing a social-cognitive model of moral behavior: The interactive influence situations and moral identity centrality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), 123–141.

Aquino, K., McFerran, B., & Laven, M. (2011). Moral identity and the experience of moral elevation in response to acts of uncommon goodness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(4), 703–718.

Aquino, K., & Reed, A. (2002). The Self-Importance of Moral Identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423–1440.

Backof, A. G., Carpenter, T. D., & Thayer, J. (2018). Auditing complex estimates: How do construal level and evidence formatting impact auditors’ consideration of inconsistent evidence? Contemporary Accounting Research, 35(4), 1798–1815.

Ballou, B., Casey, R. J., Grenier, J. H., & Heitger, D. L. (2012). Exploring the strategic integration of sustainability initiative: Opportunities for Accounting Research. Accounting Horizons, 26(2), 265–288.

Baumeister, R. F. (Ed.) (1999). The self in social psychology. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press (Taylor and Francis).

Beck, T., Bühren, C., Frank, B., & Khachtryan, E. (2020). Can honesty oaths, peer interaction, or monitoring mitigate lying? Journal of Business Ethics, 163, 467–484.

Becton, J. B., Giles, W. F., & Schraeder, M. (2008). Evaluating and rewarding OCBs: Potential consequences of formally incorporating organisational citizenship behavior in performance appraisal and reward systems. Employee Relations, 30(5), 494–514.

Bergstresser, D., & Philippon, T. (2006). CEO incentives and earnings management. Journal of Financial Economics, 80(2006), 511–529.

Blanken, I., van de Ven, N., & Zeelenberg, M. (2015). A meta-analytic review of moral licensing. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215572134

Blanken, I., van de Ven, N., Zeelenberg, M., & Meijers, M. (2014). Three attempts to replicate the moral licensing effect. Social Psychology, 45(3), 232–238.

Blasi, A. (2004). Moral functioning: Moral understanding and personality. In D. K. Lapsley & D. Narvaez (Eds.), Moral development, self, and identity (pp. 335–347). Erlbaum.

Bonner, S. E., Clor-Proell, S. M., & Koonce, L. (2014). Mental accounting and disaggregation based on the sign and relative magnitude of income statement items. The Accounting Review, 89(6), 2087–2114.

Brown, J. L., Evans, J. H., & Moser, D. V. (2009). Agency theory and participative budgeting experiments. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 21(1), 317–345.

Brunner, M., & Ostermaier, A. (2019). Sabotage in capital budgeting: The effects of control and honesty on investment decisions. European Accounting Review, 28(1), 71–100.

Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Camerer, C. (2003). Behavioral game theory: Experiments in strategic interaction. Princeton University Press.

Celse, J., & Chang, K. (2019). Politicians lie, so do I. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 88, 1311–1325.

Choi, J. W., Hecht, G., Tafkov, I. D., & Towry, K. L. (2016). Vicarious learning under implicit contracts. The Accounting Review, 91(4), 1087–1108.

Christensen, D. M. (2016). Corporate accountability reporting and high-profile misconduct. The Accounting Review, 91(2), 377–399.

Church, B. K., Hannan, R. L., & Kuang, X. J. (2012). Shared interest and honesty in budget reporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 37(3), 155–167.

Cohen, T. R., Panter, A. T., Turan, N., Morse, L., & Kim, Y. (2014). Moral character in the workplace. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(5), 943–963.

Conway, P., & Peetz, J. (2012). When does feeling moral actually make you a better person? Conceptual abstraction moderates whether past moral deeds motivate consistency or compensatory behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(7), 907–919.

Culbertson, S. S., & Mills, M. J. (2011). Negative implications for the inclusion of citizenship performance in ratings. Human Resource Development International, 14(1), 23–38.

Dalla Via, N., Perego, P., & Van Rinsum, M. (2019). How accountability type influences information searchprocesses and decision quality. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 75, 79–91.

den Nieuwenboer, N. A., da Cunha, J. V., & Treviño, L. K. (2017). Middle managers and corruptive routine translation: The social production of deceptive performance. Organizational Science, 28(5), 781–803.

Douthit, J. D., & Stevens, D. E. (2015). The robustness of honesty effects on budget proposals when the superior has rejection authority. The Accounting Review, 90(2), 467–493.

Erikson, E. H. (1964). Insight and responsibility. Norton.

Evans, J. H., Hannan, R. L., Krishnan, R., & Moser, D. V. (2001). Honesty in managerial reporting. The Accounting Review, 76(4), 537–559.

Farrell, A. M., Grenier, J. H., & Leiby, J. (2017). Scoundrels or stars? Theory and evidence on the quality of workers in online labor markets. The Accounting Review, 92(1), 93–114.

Fu, R., Kraft, A., & Zhang, H. (2012). Financial reporting frequency, information asymmetry, and the cost of equity. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 54(2–3), 132–149.

Gamma, K., Mai, R., & Loock, M. (2020). The double-edged sword of ethical nudges: Does inducing hypocrisy help or hinder the adoption of pro-environmental behaviors? Journal of Business Ethics, 161, 351–373.

Gao, F., Lisic, L. L., & Zhang, I. X. (2014). Commitment to social good and insider trading. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 57(2), 149–175.

Giacomantonio, M., De Dreu, C. K. W., Shalvi, S., Sligte, D., & Leder, S. (2010). Psychological distance boosts value-behavior correspondence in ultimatum bargaining and integrative negotiation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 824–829.

Giglere, F., Kanodia, C., Sapra, H., & Venugopalan, R. (2014). How frequent financial reporting can cause managerial short-termism: An analysis of the costs and benefits of increasing reporting frequency. Journal of Accounting Research, 52(2), 357–387.

Grenier, J. H., Pomeroy, B., & Stern, M. T. (2015). The effects of accounting standard precision, auditor task expertise, and judgment frameworks on audit firm litigation exposure. Contemporary Accounting Research, 32(1), 336–357.

GRI. (2015). G4 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines. Available at: https://www.globalreporting.org/resourcelibrary/GRIG4-Part2-Implementation-Manual.pdf

Grover, L. S. (2005). The truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth: The causes and management of workplace lying. Academy of Management Executive, 19(2), 148–157.

Haidar, F. (2017). Two Mumbai airport staff suspended for ‘fudging’ on-time data. Hindustan Times (January 20). Available at: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/mumbai-airport-staff-suspended-for-fudging-on-time-data/story-kh5oY3RgLhRIafNAtNV8OP.html

Hakim, D., Kessler, A. M., and Ewing, J. (2015). “As Volkswagen pushed to be No. 1, ambitions fueled a scandal.” New York Times, September 27, 2015 A1.

Hannan, R. L., Rankin, F. W., & Towry, K. L. (2006). The effect of information systems on honesty in managerial reporting: A behavioral perspective. Contemporary Accounting Research, 23(4), 885–918.

Hardy, S. A., & Carlo, G. (2011). Moral identity: What is it, how does it develop, and is it linked to moral action? Child Development Perspectives, 5(3), 212–218.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. The Guilford Press.

Hoi, C. K., Wu, Q., & Zhang, H. (2013). Is corporate social responsibility (CSR) associated with tax avoidance? Evidence from irresponsible CSR activities. The Accounting Review, 88(6), 2025–2059.

Jayaraman, S., & Milbourn, T. (2014). CEO equity incentives and financial misreporting: The role of auditor expertise. The Accounting Review, 90(1), 321–350.

Johannsdottir, L., & Olafsson, S. (2015). The role of employees in implementing CSR strategies. In L. O’Riordan, P. Zmuda, & S. Heinemann (Eds.), New perspectives on corporate social responsibility FOM-Edition (FOM Hochschule für Oekonomie and Management). Wiesbaden: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-06794-6_20

Johnson, J. A., Sutton, S. G., & Theis, J. (2020). Prioritizing sustainability issues: Insights from corporate managers about key decision-makers, reporting models, and stakeholder communications. Accounting in the Public Interest, 20(1), 28–60.

Johnson, S. K., Holladay, C. L., & Quinones, M. A. (2009). Organizational citizenship behavior in performance evaluations: Distributive justice or injustice? Journal of Business Psychology, 24, 409–418.

Joosten, A., van Dijke, M., Van Hiel, A., & De Cremer, D. (2014). Feel good, do good!? On consistency and compensation in moral self-regulation. Journal of Business Ethics, 123, 71–84.

Kim, Y., Park, M. S., & Wier, B. (2012). Is earnings quality associated with corporate social responsibility? The Accounting Review, 87(3), 761–796.

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Harrison, D. A., & Trevino, L. K. (2010). Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 1–31.

Koonce, L., Miller, J., & Winchel, J. (2015). The effects of norms on investor reactions to derivative use. Contemporary Accounting Research, 32(4), 1529–1554.

Kraft, A. G., Vashishtha, R., & Venkatachalam, M. (2018). Frequent financial reporting and managerial myopia. The Accounting Review, 93(2), 249–275.

Lehnert, K., Park, Y. H., & Singh, N. (2015). Research note of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: Boundary conditions and extensions. Journal of Business Ethics, 129(1), 195–219.

Lemoine, G. J., Parsons, C. K., & Kansara, S. (2015). Above and beyond, again and again: Self-regulation in the aftermath of organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(1), 40–55.

Lennox, C., Lisowsky, P., & Pittman, J. (2013). Tax aggressiveness and accounting fraud. Journal of Accounting Research, 51(4), 739–778.

Liberman, N., Sagristano, M. D., & Trope, Y. (2002). The effect of temporal distance on level of mental construal. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 523–534.

Lill, J. B. (2020). When the Boss is far away there is shared pay: The effect of monitoring distance and compensation interdependence on performance misreporting. Organizations and Society, In Press.

Lin, C., Lyau, N., Tsai, Y., Chen, W., & Chiu, C. (2010). Modeling Corporate Citizenship and Its Relationship with Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 357–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0364-x

Lord, R. G., Hannah, S. T., & Jennings, P. L. (2011). A framework for understanding leadership and individual requisite complexity. Organizational Psychology Review, 1, 104–127.

Maas, V. S., & Van Rinsum, M. (2013). How control system design influences performance misreporting. Journal of Accounting Research, 51(5), 1159–1186.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

Markus, H., & Kunda, Z. (1986). Stability and malleability of the self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(4), 858–866.

Mason, W., & Suri, S. (2012). Conducting behavioral research on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Behavior Research Methods, 44(1), 1–23.

Miller, D. T., & Effron, D. A. (2010). Psychological license: When it is needed and how it functions. In P. Z. Mark & M. O. James (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 43, pp. 115–155). Elsevier Academic Press.

Mullen, E., & Monin, B. (2016). Consistency versus licensing effects of past moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 363–385.

Murphy, P. R. (2012). Attitude, machiavellianism and the rationalization of misreporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 37(4), 242–259.

Murphy, P. R., Wynes, M., Hahn, T. A., & Devine, P. G. (2020). Why are people honest? Internal and external motivations to report honestly. Contemporary Accounting Research, 37(2), 945–981.

Nichol, J. E. (2019). The effects of contract framing on misconduct and entitlement. The Accounting Review, 94(3), 329–344.

Nussbaum, S., Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2003). Creeping dispositionism: The temporal dynamics of behavior prediction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 485–497.

Opoku-Dakwa, A., Chen, C. C., & Rupp, D. E. (2018). CSR initiative characteristics and employee engagement: An impact-based perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(5), 580–593.

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington Books.

Palmer, D. (2012). Normal organizational wrongdoing: A critical analysis of theories of misconduct in and by organizations. Oxford University Press on Demand.

Palmer, D. (2013). The new perspective on organizational wrongdoing. California Management Review, 56(1), 5–23.

Pedhazur, E. J. (1997). Multiple regression in behavioral research: Explanation and prediction (3rd ed.). Harcourt Brace.

Podaskoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Paine, J. B., & Bachrach, D. G. (2000). Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Management, 26(3), 513–563.

Podaskoff, N. P., Whiting, S. W., Podaskoff, P. M., & Blume, B. D. (2009). Individual- and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(1), 122–141.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78–92.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 89(1–2), 62–77.

Prickett, B., and Moreton, E. (2014). The effect of complexity versus the effect of naturalness on phonological learning. Carolina Digital Repository.

Rankin, F. W., Schwartz, S. T., & Young, R. A. (2008). The effect of honesty and superior authority on budget proposals. The Accounting Review, 83(July), 1083–1099.

Rasso, J. T. (2015). Construal instructions and professional skepticism in evaluating complex estimates. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 46, 44–55.

Reed, A., & Aquino, K. F. (2003). Moral identity and the expanding circles of moral regard toward out-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(6), 1270–1286.

Rennekamp, K. (2012). Processing fluency and investors’ reactions to disclosure readability. Journal of Accounting Research, 50(5), 1319–1354.

Rennekamp, K., Rupar, K. K., & Seybert, N. (2015). Impaired judgment: The effect of asset impairment reversibility and cognitive dissonance on future investment. The Accounting Review, 90(2), 739–759.

Reynolds, S. J., & Ceranic, T. L. (2007). The effects of moral judgment and moral identity on moral behavior: An empirical examination of the moral individual. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1610–1624.

Rigdon, E. E., Schumacker, R. E., & Wothke, W. (1998). A comparative review of interaction and nonlinear modeling. In R. E. Schumacker & G. A. Marcoulides (Eds.), Interaction and Nonlinear Effects in Structural Equation Modeling. Erlbaum.

Roser, C. (2015). Lies, Damned Lies, AND KPI—Part 1: Examples of Fudging [Blog post]. Available at: https://www.allaboutlean.com/kpi-lies-examples/

Sage, L., Kavusannu, M., & Duda, J. (2006). Goal orientations and moral identity as predictors of prosocial and antisocial functioning in male association football players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24(5), 455–466.

Schrand, C. M., & Zechman, S. L. C. (2012). Executive overconfidence and the slippery slope to financial misreporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 53(1–2), 311–329.

SEC. (1998). A plain-English handbook. Available at: https://www.sec.gov/pdf/handbook.pdf.

Shao, D., Aquino, K., & Freeman, D. (2008). Beyond moral reasoning: A review of moral identity research and its implications for business ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18, 513–540.

Slack, R. E., Corlett, S., & Morris, R. (2015). Exploring employee engagement with (corporate) social responsibility: A social exchange perspective on organizational participation. Journal of Business Ethics, 127, 537–548.

Starkweather, J. (2010). Categorical variables in regression: Implementation and interpretation. Benchmarks Online.

Tenbrunsel, A. E., & Messick, D. M. (1999). Sanctioning systems, decision frames, and cooperation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 684–707.

Trevino, L. K. (1986). Ethical decision making in organizations: A person-situation interactionist model. Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 601–617.

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2003). Temporal construal. Psychological Review, 110(3), 403–421.

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440–463.

Young, D. (2021). How Social Norms and Social Identification Constrain Aggressive Reporting Behavior. The Accounting Review, forthcoming.

Zhang, Y. (2008). The effects of perceived fairness and communication on honesty and collusion in a multi-agent setting. The Accounting Review, 83(4), 1125–1146.

Zhong, C., Liljenquist, K., & Cain, D. M. (2009). Moral self-regulation: Licensing and compensation. In D. De Cremer (Ed.), Psychological perspectives on ethical behavior and decision making. Information Age Publishing.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate helpful comments from Charles Cho (editor) and anonymous reviewers as well as John Anderson (discussant), Scott Asay, Jason Brown, Eddy Cardinaels, Willie Choi, Ted Christensen, Mike Durney, Devon Erickson, Harry Evans, Paul Fischer, Sarah Gochnauer, Jeff Hales, Emily Hornok, Leslie Hodder, Vicky Hoffman, Pat Hopkins, Kathryn Kadous, Khim Kelly, Theresa Libby, Chris Miller, Don Moser, Joel Owens (discussant), Jeff Pickerd, Adam Presslee, Kristi Rennekamp, Lori Shefchik Bhaskar, Greg Stone, Todd Thornock, Mike Tiller, Flora Zhou (discussant) and brownbag and workshop participants at Emory University, Indiana University, the University of Cincinnati, the University of Mississippi, the University of Pittsburgh, the 2015 BYU Accounting Research Symposium, the 2016 Management Accounting Section Meeting, the 2016 Accounting, Behavior and Organizations Section Meeting, and the 2017 Public Interest Section Meeting. We are also grateful to Stefan Hill, Andrew Kim, Jacob Lennard, Aaron McCullough, and Jordan Samet for their research assistance, and to the Scheller College of Business and Dixon School of Accounting for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Participant Payoffs

We calculated each participant’s payoff as follows:

πi = participant i's payoff; pr = the probability of a good outcome reported by the participant, from a minimum of 20% (the true probability) up to 95% in 5% increments; pt = the true probability of a good outcome (20%).

Thus, participant payoffs increased as they inflated the probability of a good outcome that they report. Participants who reported the true probability of a good outcome (20%) earned $1.50 while those who reported the maximum probability (95%) earned $3.00. Participants knew that although they could increase their own payoff by inflating the reported probability of a good outcome, doing so would decrease the payoff of other participants. Specifically, the payoff for other participants was calculated as:

\({\pi }_{i}^{\text{s}}\) = the payoff for participant i's impacted participants; pr = the probability of a good outcome reported by the participant, from a minimum of 20% (the true probability) up to 95% in 5% increments; pt = the true probability of a good outcome (20%).

Thus, each participant’s group of impacted participants shared between $0.30 (if the participant reported the probability of a good outcome to be 95%) and $6.30 (if the participant reported the true probability of a good outcome of 20%).Footnote 27

Appendix B

See Table 4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, J.A., Martin, P.R., Stikeleather, B. et al. Investigating the Interactive Effects of Prosocial Actions, Construal, and Moral Identity on the Extent of Employee Reporting Dishonesty. J Bus Ethics 181, 721–743 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04915-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04915-z