Abstract

Purpose

To examine the trajectory of psychological distress from 1 to 2 years after esophageal cancer surgery, and whether dispositional optimism could predict the risk of postoperative psychological distress.

Methods

This Swedish nationwide longitudinal study included 192 patients who had survived for 1 year after esophageal cancer surgery. We measured dispositional optimism with the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) 1 year post-surgery and psychological distress with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale 1, 1.5, and 2 years post-surgery. Latent growth curve models were used to assess the trajectory of postoperative psychological distress and to examine the predictive validity of dispositional optimism.

Results

One year after surgery, 11.5% (22 of 192) patients reported clinically significant psychological distress, and the proportion increased to 18.8% at 1.5 years and to 25.0% at 2 years post-surgery. Higher dispositional optimism predicted a lower probability of self-reported psychological distress at 1, 1.5, and 2 years after esophageal cancer surgery. For each point increase in the LOT-R sum score, the odds of psychological distress decreased by 44% (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.79).

Conclusion

The high prevalence and longitudinal increase of self-reported psychological distress after esophageal cancer surgery indicate the unmet demands for timely psychological screening and interventions. Measuring dispositional optimism may help identify patients at higher risk of developing psychological distress, thereby contributing to the prevention of postoperative psychological distress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the seventh most common cancer globally [1]. It carries poor overall 5-year survival rate (< 20%) [2] and ranks the sixth leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. The mainstay of curative treatment, esophagectomy, is a highly invasive operation, which improves survival but entails high risk of postoperative complications and substantially impaired health related quality of life (HRQL) [3]. The life-threatening cancer diagnosis and major surgery are traumatic stressors for patients, leading to increased symptoms of psychological distress before and after esophageal cancer surgery [4,5,6]. Based on a prospective hospital-based cohort study carried out in London, 33%, 28%, and 37% of patients had anxiety prior to surgery, at 6 and 12 months after surgery, respectively [5]. Contrary to the stable trajectory of anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms first increase and then level off [5]. Prior to surgery, 20% of patients reported depression, and the proportion increased to 27% and 32% at 6 and 12 months after surgery, respectively [5]. However, the trajectory of psychological distress after 1 year post-surgery remains unclear. Revealing this trajectory may help healthcare providers and patients build proper expectations about postoperative recovery, thus taking timely measures to improve psychological adjustment.

Previous studies have identified some risk factors for psychological distress including younger age, female sex, cohabitating status, low education level, and tumor histology [7, 8]. However, patients with similar characteristics in these aspects still reported varied psychological status, which suggests that other factors, such as personality traits, may also play an important role in the psychological adjustment after esophageal cancer surgery.

Dispositional optimism is a personality trait referring to the expectation that positive rather than negative outcomes will happen in the future [9]. It has been shown that higher dispositional optimism is associated with a lower risk of developing psychological distress in patients with heart disease or other subtypes of cancer such as breast cancer, urogenital cancer, head and neck cancer, and oral cavity cancer [10,11,12,13,14]. However, whether this association exists in patients with esophageal cancer remains unknown. Clarifying the predictive effect of dispositional optimism on psychological distress may help identify high-risk patients and contribute to the implementation of timely and personalized interventions. In addition, given that dispositional optimism could be increased through psychological interventions such as Best Possible Self exercise and Cognitive Behaviour Therapy [15], it may be a potential intervention target to partly prevent psychological distress after esophageal cancer surgery.

In this study, we aim to explore the trajectory of psychological distress from 1 to 2 years after esophageal cancer surgery, and also to examine whether dispositional optimism predicted this trajectory.

Methods

Study design and data collection

Data for this longitudinal study is from a prospective, ongoing Swedish-nationwide cohort study entitled Oesophageal Surgery on Cancer patients—Adaptation and Recovery (OSCAR). Detailed description of the OSCAR study can be found elsewhere [16, 17]. In brief, it includes patients undergoing esophagectomy for cancer in Sweden from January 1, 2013 and onwards. Potential patients are identified by contacting pathology departments at eight hospitals performing esophagectomy in Sweden. At 1 year after esophageal cancer surgery, all survivors are invited to participate in the study. Patient-reported outcomes are collected from 1 year until 5 years after surgery through personal interviews and mailing paper questionnaires. Patients’ demographics are retrieved from the national health data registries and Swedish Longitudinal Integration Database for Health Insurance and Labor Market Studies. Clinical data are collected from medical charts, the Swedish Patient Registry and the Swedish Cancer Registry. Mortality information is obtained through linkage to the Swedish Register of the Total Population and the Swedish cause of death register. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (diary number 2013/844–31/1, 2015/2142–32, 2016/1696–32/1, 2017/1301–32, 2018/1447–32, 2019–04,289 and 2020–01,304) and written consents were obtained from all participants before inclusion.

Study participants

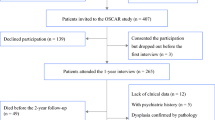

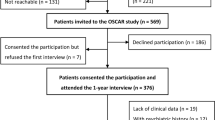

Between January 1, 2013 and February 28, 2018, 647 patients underwent esophagectomy for cancer in Sweden. Among them, 154 patients died within 1 year post-surgery and 86 patients lacked valid contact information. Thus, 407 patients were invited to participate in the OSCAR study; 265 (65%) patients consented and attended the first (1-year) interview. Nonparticipation was mainly related to unwillingness, severe illness, and cancer recurrence [16]. We further excluded patients who died within 2 years after surgery (n = 49), with histories of psychological disorders (n = 5), with dysphasia confirmed by pathological histology (n = 3), and with missing data in clinical information, patient-reported outcomes and/or sociodemographic information (n = 16). Thus, the final analysis included 192 patients; of these, 170 and 156 patients answered the 1.5- and 2-year follow-up questionnaires, respectively.

Psychological distress

Psychological distress was measured repeatedly at 1, 1.5, and 2 years after surgery using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [18, 19], which is a well-validated and widely used questionnaire consisting of anxiety and depression subscales [18, 19]. Both subscales contain seven questions and each question is scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3, with a higher score representing more severe symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha for the anxiety and depression subscales were 0.83 and 0.74, respectively. The correlation between the two subscales was 0.57. A score ≥ 8 on each subscale is indicative of a “possible-probable” case of anxiety or depression, respectively [18]. Because anxiety and depression usually coexist [20], we treated psychological distress as a binary outcome and classified patients scoring ≥ 8 on either subscale as having clinically significant psychological distress.

Dispositional optimism

Dispositional optimism was assessed at 1 year after surgery with the validated Swedish version of Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) [21, 22]. It consists of three positively worded items and three negatively worded items [21, 22]. Patients were asked to report their agreement with each five-point Likert item, ranging from 0 (“strongly disagree”) to 4 (“strongly agree”) [22].

The dimensionality of LOT-R remains controversial and no study has assessed its factor structure among patients with esophageal cancer. Therefore, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses (see Supplementary Content 1). In the best fitting model, the loading of the first negatively worded item was negative, even though its score had been reversed to account for the negative wording. Moreover, this item had bimodal response distribution and equivocal correlations with both positively worded items and negatively worded items, indicating that a substantial proportion of the participants most likely misread it. Thus, we removed this item and reassessed the factor structure based on the remaining five items. The model assuming one factor (dispositional optimism) with correlated errors between the two reversed negatively worded items was adopted because it had the best model fit and strong theoretical base. The internal reliability estimated by McDonald’s omega for this model was 0.49 [95% bootstrapped confidence interval (CI), 0.31 to 0.62]. We summed up the five items, of which the two negatively worded items were reversed. A higher LOT-R sum score represents higher dispositional optimism.

Statistical analysis

We compared the LOT-R sum score between patients with different sociodemographic and clinical characteristics using Student’s t-test and ANOVA. Latent growth curve model with maximum likelihood estimator and logit link was used to explore the trajectory of psychological distress from 1 to 2 years after esophageal cancer surgery [23]. This model includes two random parameters, an intercept and a slope [24]. Detailed descriptions about this model are presented in the Supplementary Content 2. In addition, there were very few missing data in HADS and LOT-R, which were handled with mean imputation [25].

In order to assess whether dispositional optimism predicted the risk of psychological distress, we regressed the random intercept on the LOT-R sum score. Three hierarchical models were built to adjust for potential confounders. Model A was a crude model. Model B adjusted for sociodemographic covariates including age, sex, cohabitation status and education level, which are previously identified confounders. Model C further adjusted for clinical factors including comorbidity, neoadjuvant therapy, tumor stage, histology, and postoperative complication within 30 days post-surgery, which are potential but unidentified confounders. Details about the analysis process including model diagrams are presented in the Supplementary Content 2. In addition, we compared model B and model C using the likelihood ratio test.

Because the reliability analysis indicated that roughly half of the variation in the LOT-R sum score could be attributed to measurement error, and measurement error in the exposure can attenuate the regression coefficient [26], we conducted a sensitivity analysis using a latent (i.e., error free) factor to represent dispositional optimism. Three similar hierarchical models were built and related model diagrams are presented in Supplementary Content 2.

We used Mplus 8.2 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, USA) to build the latent growth curve models and Stata 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) for data cleaning. All 95% CIs were 2-sided.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 192 patients. The mean age was 66.3 years [standard deviation (SD), 8.5; range, 38.2 to 83.7], and 85.4% patients were male. The mean of LOT-R sum score was 15.2 (SD, 3.0; range, 6 to 20). There was no statistically significant difference in the LOT-R sum score between patients with different sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Trajectory of psychological distress from 1 to 2 years post-surgery

One year after surgery, 11.5% (22 of 192) patients reported clinically significant psychological distress, and the proportion increased to 18.8% (32 of 170) at 1.5 years and to 25.0% (39 of 156) at 2 years post-surgery. The random intercept model with linear slope fit the data well, and the estimated probability of clinically significant psychological distress doubled from 1 year (11.8%) to 2 years (25.1%) after surgery, which is in line with the observed proportions (Fig. 1). In addition, there was no statistically significant variation in this longitudinal growth trajectory of psychological distress (p = 0.305), whereas substantial individual differences were found in the probability of reporting psychological distress at 1 year after surgery (variance = 23.17, p = 0.016).

Predictive effect of dispositional optimism on psychological distress

Higher dispositional optimism was associated with a lower risk of psychological distress at 1, 1.5, and 2 years after surgery and this association was not modified by time. Figure 2 displays the estimated probability of psychological distress as a function of LOT-R sum score, separated by different time points after surgery. In the crude model, for each point increase in the LOT-R sum score, the odds of reporting psychological distress decreased by 44% [odds ratio (OR) 0.56, 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.80; Table 2, model A]. The results remained almost unchanged after adjusting for sociodemographic covariates and clinical factors, with ORs equalling to 0.56 (95% CI, 0.40 to 0.79) and 0.55 (95% CI, 0.39 to 0.78), respectively (Table 2, model B and C). However, based on the likelihood ratio test, compared with the model B with adjustment for sociodemographic covariates, the model C with further adjustment for clinical factors did not show better model fit.

Estimated probability of psychological distress as a function of LOT-R sum score for three assessment time points after esophageal cancer surgery. Note. LOT-R: Life Orientation Test-Revised. The estimated probability is calculated from latent growth curve model, holding other included variables (age, sex, cohabitating status and education level) at their mean values

Sensitivity analysis fitting a latent factor to represent dispositional optimism also demonstrated similar results among the three hierarchical models, with fully standardized log-odds equalling to − 0.55, − 0.58, and − 0.66, respectively (Table 2, sensitivity analysis). However, the coefficients from the sensitivity analysis were larger than the coefficients from the main analysis. For example, in the crude model, with 1 SD increase in the dispositional optimism, the log-odds decreased 0.36 SD in the main analysis, whereas the log-odds decreased 0.55 SD in the sensitivity analysis (Table 2, model A). This difference is most likely because measurement error in the exposure could attenuate the observed coefficient [26], and the sensitivity analysis using latent factor has removed the measured error in the LOT-R.

Discussion

This Swedish nationwide population-based longitudinal study showed that the proportion of self-reported clinically significant psychological distress roughly doubled from 1 to 2 years after esophageal cancer surgery. Moreover, higher dispositional optimism predicted a lower risk of psychological distress at 1, 1.5, and 2 years post-surgery.

The self-reported psychological distress at 1 year after esophageal cancer surgery was 11.5% in the current study, which was lower than the proportions reported by one previous study conducted in the UK [5]. The inconsistency might be because the previous study was only conducted in one British hospital while the current study was Swedish nationwide population–based. Moreover, another previous study with large sample size using British hospital and primary care databases has found that 13.9% patients had psychiatry morbidity based on the diagnosis and prescription codes within 1 year after esophageal cancer surgery [27], which is similar to the proportion found in the current study. In addition, given that non-participation in the current study was mainly related to unwillingness, severe illness and cancer recurrence [16], the non-participants might suffer more from psychological distress compared with the participants, which could make the observed proportion underestimated.

The current study found that the proportion of psychological distress increased from 1 to 2 years after esophageal cancer surgery. This indicates unmet demands for early psychological screening and timely interventions to improve mental health. After esophageal cancer surgery, patients often face lingering symptoms (e.g., dumping, reflux and eating difficulty), malnutrition, decreased HRQL and risk of cancer recurrence [3, 28]. Moreover, most patients with esophageal cancer are old [29, 30], and may have comorbidities relating to aging and risk factors associated with cancer [29]. These chronic stresses could induce increased glucocorticoid stress hormones, cause structural change in the brain, and result in persistent vulnerability to mental illness [31], therefore leading to increased psychological distress over time after esophageal cancer surgery. Interventions helping patients cope with these postoperative challenges may contribute to the improvement of mental health.

The present study further found that higher dispositional optimism predicted a lower probability of self-reported psychological distress after esophageal cancer surgery. This result is in line with previous studies [10,11,12,13,14]. Potential mechanisms for the protective effect of dispositional optimism may be related to coping strategies, goal adjustment and social support [32,33,34,35,36,37]. Studies have shown that more optimistic people seem to be more flexible in coping and goal adjustment. When the situation is perceived as controllable, more optimistic people tend to persistently seek measures to overcome the adversity, but if the situation is perceived as uncontrollable, they are also more likely to accept the reality and disengage from the unattainable goals rapidly [32,33,34,35]. These strategies may lead to less negative experiences and rumination and therefore better mental health [32,33,34,35]. In addition, people with higher dispositional optimism are prone to receive more social support due to their positive outlook [36, 37], which may help relieve the perceived stress and thus reduce the risk of psychological distress.

The predictive effect of dispositional optimism has both clinical and research implications. Dispositional optimism may not only be used to predict prognosis, but also help differentiate patients with similar sociodemographic and clinical characteristics to identify those needing additional psychological support. Early identification of high-risk patients could lead to more frequent mental health surveillance and timely psychological interventions, thereby ameliorating or perhaps even preventing later psychological distress. Moreover, compared with general surveillance, such a risk-based strategy may be more cost-effective and could allocate medical resources to patients with more dire needs. In addition, because dispositional optimism appears at least partly modifiable through psychological interventions [15], it would be worth investigating whether psychological distress after esophageal cancer surgery could be prevented or treated through increasing dispositional optimism. Results from the present study provide a base for future interventional studies.

This study has several methodological strengths. First, it is the first longitudinal study examining the association between dispositional optimism and psychological distress among patients with esophageal cancer. Second, the prospective, nationwide, and longitudinal design facilitates its generalizability and enables the assessment of trajectory over time. Third, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analysis to determine the proper factor structure of LOT-R, and to the best of our knowledge, it is the first study assessing the dimensionality of LOT-R among patients with esophageal cancer. Moreover, in addition to the observed LOT-R sum score, we used a latent factor to represent dispositional optimism, which further confirmed the predictive validity of dispositional optimism by removing the potential bias attributable to measurement error in the LOT-R.

This study also has limitations. First, psychological distress was measured by a self-reported screening questionnaire HADS instead of being defined by clinical diagnosis. Although HADS has been recommended to be used in oncology settings [38, 39], such subjective reporting might result in underestimation [40]. Second, less optimistic patients and those suffering from psychological distress might be prone to decline the participation, withdraw or miss the follow-ups, which could make the observed proportion of psychological distress and the protective effect of dispositional optimism underestimated. Third, this observational study found that dispositional optimism predicted postoperative psychological distress, but prediction does not mean causality. Unmeasured common causes such as genetic factors [41] could result in a spurious association between dispositional optimism and psychological distress, and whether increasing dispositional optimism could ameliorate psychological distress needs to be examined by future interventional studies.

In conclusion, this study found that psychological distress increased over time from 1 to 2 years after esophageal cancer surgery and higher dispositional optimism predicted a lower risk of psychological distress. It highlights the need for timely psychological screening and interventions. In addition, early assessment of dispositional optimism may help identify patients with higher risk of developing psychological distress after esophageal cancer surgery, thereby providing personalized mental health surveillances and tailored psychological interventions, and contributing to the prevention of postoperative psychological distress.

Data and materials availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Code availability

Codes supporting the findings of this study are stored at the server of Karolinska Institutet, and they can be made available upon request.

Change history

25 February 2022

The original version of this paper was updated to add the missing compact agreement Open Access funding note.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F (2021) Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71(3):209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

Office for National Statistics (2019) Cancer survival in England - adults diagnosed. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/datasets/cancersurvivalratescancersurvivalinenglandadultsdiagnosed. Accessed 27 Jun 2021

Lagergren J, Smyth E, Cunningham D, Lagergren P (2017) Oesophageal cancer. Lancet 390(10110):2383–2396. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31462-9

Johansson R, Carlbring P, Heedman A, Paxling B, Andersson G (2013) Depression, anxiety and their comorbidity in the Swedish general population: point prevalence and the effect on health-related quality of life. PeerJ 1:e98. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.98

Hellstadius Y, Lagergren J, Zylstra J, Gossage J, Davies A, Hultman CM, Lagergren P, Wikman A (2017) A longitudinal assessment of psychological distress after oesophageal cancer surgery. Acta Oncol 56(5):746–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2017.1287945

Hellstadius Y, Lagergren J, Zylstra J, Gossage J, Davies A, Hultman CM, Lagergren P, Wikman A (2016) Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression among esophageal cancer patients prior to surgery. Dis Esophagus 29(8):1128–1134. https://doi.org/10.1111/dote.12437

Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, Greig D (2012) Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord 141(2–3):343–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025

Hellstadius Y, Lagergren P, Lagergren J, Johar A, Hultman CM, Wikman A (2015) Aspects of emotional functioning following oesophageal cancer surgery in a population-based cohort study. Psychooncology 24(1):47–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3583

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Segerstrom SC (2010) Optimism. Clin Psychol Rev 30(7):879–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006

Ai AL, Carretta H (2020) Optimism/hope associated with low anxiety in patients with advanced heart disease controlling for standardized cardiac confounders. J Health Psychol 25(13–14):2520–2527. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105319864633

David D, Montgomery GH, Bovbjerg DH (2006) Relations between coping responses and optimism-pessimism in predicting anticipatory psychological distress in surgical breast cancer patients. Pers Individ Dif 40(2):203–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.05.018

Zenger M, Brix C, Borowski J, Stolzenburg JU, Hinz A (2010) The impact of optimism on anxiety, depression and quality of life in urogenital cancer patients. Psychooncology 19(8):879–886. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1635

Horney DJ, Smith HE, McGurk M, Weinman J, Herold J, Altman K, Llewellyn CD (2011) Associations between quality of life, coping styles, optimism, and anxiety and depression in pretreatment patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 33(1):65–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.21407

Rajandram RK, Ho SM, Samman N, Chan N, McGrath C, Zwahlen RA (2011) Interaction of hope and optimism with anxiety and depression in a specific group of cancer survivors: a preliminary study. BMC Res Notes 4:519. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-4-519

Malouff JM, Schutte NS (2016) Can psychological interventions increase optimism? A meta-analysis. J Posit Psychol 12(6):594–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1221122

Schandl A, Johar A, Anandavadivelan P, Vikstrom K, Malberg K, Lagergren P (2020) Patient-reported outcomes 1 year after oesophageal cancer surgery. Acta Oncol 59(6):613–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2020.1741677

Liu Y, Pettersson E, Schandl A, Markar S, Johar A, Lagergren P (2021) Higher dispositional optimism predicts better health-related quality of life after esophageal cancer surgery: a nationwide population-based longitudinal study. Ann Surg Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-10026-w

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D (2002) The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 52(2):69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3

Hranov LG (2007) Comorbid anxiety and depression: illumination of a controversy. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 11(3):171–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651500601127180

Muhonen T, Torkelson EVA (2013) Kortversioner av frågeformulär inom arbets- och hälsopsykologi—om att mäta coping och optimism. Nordisk Psykologi 57(3):288–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291463.2005.10637375

Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW (1994) Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol 67(6):1063–1078. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063

Lee TK, Wickrama K, O’Neal CW (2018) Application of latent growth curve analysis with categorical responses in social behavioral research. Struct Equ Modeling 25(2):294–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2017.1375858

Duncan TE, Duncan SC (2009) The ABC’s of LGM: an introductory guide to latent variable growth curve modeling. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 3(6):979–991. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00224.x

Bell ML, Fairclough DL, Fiero MH, Butow PN (2016) Handling missing items in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): a simulation study. BMC Res Notes 9(1):479. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-2284-z

Hutcheon JA, Chiolero A, Hanley JA (2010) Random measurement error and regression dilution bias. BMJ 340:c2289. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c2289

Bouras G, Markar SR, Burns EM, Mackenzie HA, Bottle A, Athanasiou T, Hanna GB, Darzi A (2016) Linked hospital and primary care database analysis of the incidence and impact of psychiatric morbidity following gastrointestinal cancer surgery in England. Ann Surg 264(1):93–99. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001415

Pinto E, Cavallin F, Scarpa M (2019) Psychological support of esophageal cancer patient? J Thorac Dis 11(Suppl 5):S654–S662. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2019.02.34

Smyth EC, Lagergren J, Fitzgerald RC, Lordick F, Shah MA, Lagergren P, Cunningham D (2017) Oesophageal cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 3:17048. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.48

Cancer Research UK (2021) Oesophageal cancer statistics. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/oesophageal-cancer#heading-Zero. Accessed 29 July 2021

Chetty S, Friedman AR, Taravosh-Lahn K, Kirby ED, Mirescu C, Guo F, Krupik D, Nicholas A, Geraghty A, Krishnamurthy A, Tsai MK, Covarrubias D, Wong A, Francis D, Sapolsky RM, Palmer TD, Pleasure D, Kaufer D (2014) Stress and glucocorticoids promote oligodendrogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Mol Psychiatry 19(12):1275–1283. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2013.190

Nes LS, Segerstrom SC (2006) Dispositional optimism and coping: a meta-analytic review. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 10(3):235–251. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_3

Buyukasik-Colak C, Gundogdu-Akturk E, Bozo O (2012) Mediating role of coping in the dispositional optimism-posttraumatic growth relation in breast cancer patients. J Psychol 146(5):471–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2012.654520

Ramirez-Maestre C, Esteve R, Lopez-Martinez AE, Serrano-Ibanez ER, Ruiz-Parraga GT, Peters M (2019) Goal adjustment and well-being: the role of optimism in patients with chronic pain. Ann Behav Med 53(7):597–607. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kay070

Willis K, Timmons L, Pruitt M, Schneider HL, Alessandri M, Ekas NV (2016) The relationship between optimism, coping, and depressive symptoms in hispanic mothers and fathers of children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 46(7):2427–2440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2776-7

Trunzo JJ, Pinto BM (2003) Social support as a mediator of optimism and distress in breast cancer survivors. J Consult Clin Psychol 71(4):805–811. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.805

Garner MJ, McGregor BA, Murphy KM, Koenig AL, Dolan ED, Albano D (2015) Optimism and depression: a new look at social support as a mediator among women at risk for breast cancer. Psychooncology 24(12):1708–1713. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3782

Castelli L, Binaschi L, Caldera P, Mussa A, Torta R (2011) Fast screening of depression in cancer patients: the effectiveness of the HADS. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 20(4):528–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01217.x

Annunziata MA, Muzzatti B, Altoe G (2011) Defining hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) structure by confirmatory factor analysis: a contribution to validation for oncological settings. Ann Oncol 22(10):2330–2333. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdq750

Thalen-Lindstrom AM, Glimelius BG, Johansson BB (2016) Identification of distress in oncology patients: a comparison of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and a Thorough Clinical Assessment. Cancer Nurs 39(2):E31-39. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000267

Mosing MA, Zietsch BP, Shekar SN, Wright MJ, Martin NG (2009) Genetic and environmental influences on optimism and its relationship to mental and self-rated health: a study of aging twins. Behav Genet 39(6):597–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-009-9287-7

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients in the OSCAR study and the patient representatives in our research partnership group for their participation. We thank our OSCAR project team for their contribution in data collection and validation.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. The OSCAR study is supported by the Swedish Cancer Society (grant number 180685); the Region Stockholm ALF (grant number LS 2018–1157); and the Cancer Research Funds of Radiumhemmet (grant number 171103). Yangjun Liu is supported by the Karolinska Institutet and China Scholarship Council joint program. Pernilla Lagergren is supported by the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) for her position at Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom. The funding sources have not been involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation and publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: All authors.

Methodology: All authors.

Data validation and analyses: Yangjun Liu, Erik Pettersson, Asif Johar.

Data interpretation: All authors.

Writing—original draft preparation: Yangjun Liu.

Writing—review and editing: All authors.

Funding acquisition: Pernilla Lagergren, Yangjun Liu.

Provision of study materials: Pernilla Lagergren.

Supervision: Erik Pettersson, Anna Schandl, Sheraz Markar, Asif Johar, Pernilla Lagergren.

Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (diary number 2013/844–31/1; 2015/2142–32; 2016/1696–32/1; 2017/1301–32; 2018/1447–32; 2019–04289 and 2020–01304). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent regarding publishing their data.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Pettersson, E., Schandl, A. et al. Psychological distress after esophageal cancer surgery and the predictive effect of dispositional optimism: a nationwide population-based longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer 30, 1315–1322 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06517-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06517-x