Abstract

A better understanding of the social-structural factors that influence HIV vulnerability is crucial to achieve the goal of ending the HIV epidemic by 2030. Given the role of neighborhoods in HIV outcomes, synthesis of findings from such research is key to inform efforts toward HIV eradication. We conducted a systematic review to examine the relationship between neighborhood-level factors (e.g., poverty) and HIV vulnerability (via sexual behaviors and substance use). We searched six electronic databases for studies published from January 1, 2007 through November 30, 2017 (PROSPERO CRD42018084384). We also mapped the studies’ geographic distribution to determine whether they aligned with high HIV prevalence areas and/or the “Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for the United States”. Fifty-five articles met inclusion criteria. Neighborhood disadvantage, whether measured objectively or subjectively, is one of the most robust correlates of HIV vulnerability. Tests of associations more consistently documented a relationship between neighborhood-level factors and drug use than sexual risk behaviors. There was limited geographic distribution of the studies, with a paucity of research in several counties and states where HIV incidence/prevalence is a concern. Neighborhood influences on HIV vulnerability are the consequence of centuries-old laws, policies and practices that maintain racialized inequities (e.g., racial residential segregation, inequitable urban housing policies). We will not eradicate HIV without multi-level, neighborhood-based approaches to undo these injustices. Our findings inform future research, interventions and policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

HIV incidence rates in the United States (U.S.) have decreased and subsequently stabilized in the overall population [1]. However, while rates continue to decline in some groups (e.g., people who inject drugs, White men who have sex with men [MSM]), they increase or remain stable among others (e.g., Black MSM, Latinx MSM) [1]. Socially and economically disadvantaged populations experience heightened HIV vulnerability/risk of acquiring HIV; disease burden and prevention innovations are not equally distributed across populations. With sexual activity and injection drug use as the leading causes of HIV transmission, it is easy to place the onus of HIV inequities on people engaged in these behaviors. However, this negates the fact that researchers consistently demonstrate that highly affected groups are not “more risky” than other populations [2]. There are broader social-structural influences at play that shape not only individual behaviors, but also the concentration of HIV in an individual’s networks, which ultimately affects HIV vulnerability.

Brawner coined the term “geobehavioral vulnerability to HIV” to highlight that when examining HIV disease burden, one must acknowledge that it is not just what people do, but also where they do it, and with whom [3]. Where a person lives and who is in their networks is critical to understanding HIV inequities; this, however, is not always a choice. In the U.S., there are segregated geographies and constrained social and sexual networks that result from the historical legacies of slavery and institutional racial discrimination [4]. A host of social (e.g., White flight) and structural (e.g., mortgage redlining) factors govern where individuals live, as well as who is in their networks. This relegates some individuals (e.g., those from socially disadvantaged backgrounds) to neighborhoods and other geosocial spaces with limited resources. This directly affects risk for HIV through factors such as concentrated disadvantage, which is associated with limited health-related services, and increases resultant disease burden. A better understanding of the social-structural factors that increase or protect against HIV risk is crucial to the goal of ending the HIV epidemic. Neighborhoods are a concrete place to start.

The role of neighborhood-level factors in health is well documented in the literature [5]. There is increasing attention given to the mechanisms by which neighborhoods shape sexual risk and substance use [6,7,8]. Factors such as poverty/concentrated disadvantage, social capital and limited health-related resources are associated with HIV-related health disparities [9, 10]. Yet there is a paucity of literature to integrate findings across studies, which limits our ability to identify modifiable targets for neighborhood-level HIV prevention initiatives.

While neighborhoods themselves cannot cause HIV transmission, they do have social and psychological implications for the individuals who live and engage in those spaces [9]. Neighborhoods operate to enable or constrain individual behaviors and thus contribute to HIV vulnerabilities. Researchers have examined the impact of neighborhood on HIV risk, but as a whole, the mechanisms by which neighborhoods influence HIV vulnerability have yet to be well articulated. We conducted a systematic review to examine the relationship between neighborhood-level factors (e.g., poverty) and HIV vulnerability (via sexual behaviors and substance use) to inform future research, interventions and policies to reduce HIV disease burden in highly affected areas.

Methods

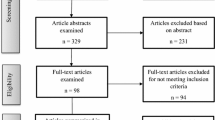

This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42018084384), a database of prospectively registered systematic reviews. We followed current Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines [11]. We searched six electronic reference databases (PubMed, Medline, PsychINFO, Social Sciences Citation Index [SSCI], the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL], and Sociological Abstracts). Our Boolean search strategy was developed by RJ, a biomedical sciences librarian. We used broad search terms relevant to neighborhoods (e.g., “neighborhood*”, “residence characteristics”, “communities”, “social environment”) and the outcomes (e.g., “risk factors”, "substance use”, “condom use”; see Table 1). The search was limited to data from U.S. studies published in English with abstracts and full-text available. The electronic reference database searches were conducted in January 2017 and updated in November 2017. We searched databases from January 1, 2007 through November 30, 2017 since the early 2000s experienced an uptick in work on neighborhood effects, as well as to enhance implications for current HIV prevention initiatives with more recent literature (Fig. 1).

Study Selection and Data Extraction

The initial search yielded a total of 2229 articles. RJ created an EndNote X8 library for data management and independently screened titles and abstracts to identify full-text articles for final eligibility review. We considered empirical articles (including qualitative and quantitative studies) with a specific focus on the relationship between neighborhoods and HIV risk behaviors. Articles were included if they: (a) measured neighborhood-level factors (e.g., poverty), (b) measured sexual risk behavior(s) (e.g., multiple sexual partners) and/or substance use/abuse outcomes (e.g., injection drug use), and (c) examined and reported on the relationship between neighborhood-level factors and HIV risk behaviors in the analyses. Articles with a primary focus on HIV outcomes (e.g., testing, medication adherence), dissertations, non-peer reviewed publications, commentaries, literature reviews and other conceptual/theoretical work, and articles that did not expressly address neighborhood-level influences on HIV risk behaviors were excluded.

After RJ excluded duplicates (n = 565) and 1438 titles and abstracts that did not meet the inclusion criteria, BMB and JK independently reviewed the remaining 226 full-text articles for final inclusion. They each created independent lists of articles to include/exclude, with a cumulative total of 60 articles between them for consideration. They reached initial agreement on 47 of the 60 articles, and held subsequent meetings with co-authors to reach consensus on 13 articles where there were disagreements. The co-authors made a determination to exclude these 13 articles from the review as they did not strictly adhere to the inclusion criteria (e.g., the studies did not provide adequate measurement or definition of neighborhoods in the analyses). Eight articles that were not identified in the search strategy but were relevant to the topic were discovered by hand-searching the references lists in the included articles. With the 47 articles identified from the search strategy, and eight discovered in the hand-search, complete agreement was reached by all authors on the final 55 articles included in this review.

JAB and BFC conducted data extraction based on a protocol for key study characteristics including: study year(s) and location, design, individual and neighborhood sample size and description, how neighborhoods were definition/operationalized, individual-level variables, neighborhood-level variables, outcome variables, key findings/conclusion, and directions for future research. We wanted to determine whether the study locations mapped onto areas with high HIV prevalence and/or were in the “Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America” (EHE)—a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) initiative to reduce new HIV infections in the U.S. by 90% by 2030 [12]. The EHE prioritizes efforts in 57 jurisdictions, including 48 counties, Washington, DC, San Juan, Puerto Rico, and seven states with a significant number of HIV diagnoses in rural areas (Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, Mississippi, Alabama, Kentucky, and South Carolina). SB created maps in ArcGIS 10.6 (ESRI, Redlands, CA) to visualize the geographic distribution of the studies.

Results

Of the 55 articles included in this review, 44 were quantitative, 8 were qualitative and three were mixed or multi-method studies (see Table 2). While the majority of the studies focused on adult populations, 9 included youth samples. The majority included participants regardless of race or ethnicity and had samples experiencing socioeconomic challenges (e.g., homelessness). Black/African American populations were the predominant focus among the studies targeted to specific racial or ethnic groups (n = 14); only one study explicitly focused on a Latinx population. The majority did not specify sexual identity; 16 studies focused on MSM, bisexual men and/or transwomen.

Four key findings were noted: (a) there is substantial variability in how authors define and operationalize neighborhood-level factors; (b) most sexual risk behavior studies focus on condom use instead of other outcomes, and most substance use studies focus on injection drugs instead of alcohol or other drugs; (c) tests of associations more consistently document a relationship between neighborhood-level factors and drug use than sexual risk behaviors; and (d) there is limited geographic distribution of studies, with a paucity of research in several populous metropolitan areas where HIV incidence/prevalence is a concern.

Definition and Operationalization of Neighborhood-Level Factors

The majority of the studies reviewed defined neighborhoods in terms of administrative boundaries such as region of the U.S., metropolitan statistical areas, census tracts or block groups, or a combination of the above (n = 48). One study did examine apartment complexes, providing a more granular analysis of the relationship between neighborhood social milieu and sexual risk [13]. Some also chose nontraditional definitions such as groups of individuals with existing social relationships and interaction patterns [14] or locales dominated by gay men (i.e., gay neighborhood residence versus non-residence) [15]. Others allowed the study participants to define their neighborhoods relative to historical or social markers [16, 17]. Neighborhood-level variables of interest included but were not limited to sociodemographics (e.g., percentage of adults in the zip code with a college education), HIV incidence and prevalence rates, social capital (e.g., trust and connections among community members), indicators of structural disadvantage in the built environment (e.g., vacant housing), community violence and racial residential segregation. Fewer studies examined factors such as social and geographic distance [18], or spatial clustering of locations for drug and alcohol use [19].

HIV Vulnerability Outcomes of Interest

Sexual risk behaviors were the main outcome in most of the quantitative studies (n = 28; see Table 3); condom use was the most commonly reported outcome. Articles related to sexual risk also included primary outcomes of HIV/STI incidence, number of sexual partners, sexual debut, exchange/transactional sex and behavioral norms. One study measured participants’ perceptions of their partner’s risk and concurrency [20]. For those that focused on substance use (n = 10), injection drug use was the most prominent, followed by alcohol. One study also examined participants’ membership in high prevalence drug networks [21]. Eight articles included sexual and substance use behaviors as primary outcomes, examining both behaviors such as receptive/distributive syringe sharing and number of sexual partners.

Relationships Between Neighborhood-Level Factors and HIV Vulnerability

Multiple neighborhood-level factors were associated with heightened HIV vulnerability, but this relationship varied by key factors including how neighborhood condition was defined (objective vs subjective) and whether HIV vulnerabilities stemmed from drug use or sexual risk behavior (see Table 4).

Objective Measurements

Living in a more disadvantaged neighborhood was associated with HIV vulnerability when assessed using objective measures of disadvantage such as existing data on percentage of residents living below the federal poverty level, violent crime rates and number of vacant housing units. Six studies indicated a relationship between HIV vulnerability and neighborhood-level factors based on examinations of economic indicators (i.e., income level, poverty) and HIV incidence as well as sexual network factors (e.g., sexual network density among Black and Latino young MSM). Buot et al. [22] found that income inequality and poverty were associated with elevated HIV incidence in cities. Income inequality and lower socioeconomic status was also consistently associated with increased risk of HIV transmission among heterosexuals and MSM. Four studies indicated that communities experiencing heightened HIV prevalence and risk behaviors contained individuals more likely to have dense sexual networks or networks that were spatially constrained [18, 19, 23, 24].

Neighborhood Composition

Fourteen studies examined neighborhood composition and HIV risk behavior, mainly focusing on the concentration of racial/ethnic and sexual minorities. Findings regarding racial and ethnic neighborhood composition and HIV risk behavior are mixed although ethnic heterogeneity was protective against HIV in two studies [22, 25]. For the other studies, one found that a larger African American neighborhood composition was protective against drug risk and sexual risk behaviors [26], another found greater presence of African Americans was associated with increased sexual risk behavior [27], and another did not identify a relationship between ethnic heterogeneity and HIV risk [28]. Of note, Knittel et al. [29] found that the incarceration rates of African American males increases HIV vulnerability via increased sexual partnerships at the community level. Neaigus et al. [30] looked at community bridging—sexual ties among individuals that bring sexually transmitted HIV from one locale to another—and discovered a greater percentage of Black or Latinx residents in high HIV-spread communities (high bridging and high HIV prevalence), and a greater percentage of Black residents in hidden bridging communities (high bridging and low HIV prevalence). Pachankis et al. [31] examined HIV transmission risk (e.g., number of condomless anal or vaginal sex acts with serodiscordant and unknown-status partners) among gay and bisexual migrants to New York City and found a higher odds of engaging in sexual risk behaviors among individuals who came from a smaller town, had recently arrived, and moved to pursue opportunity.

Three studies indicated that a higher composition of MSM in neighborhoods was associated with sexual risk (e.g., unprotected anal intercourse) [15, 32, 33]. One study did not find this association [34]. Tobin et al. [35] reported on spatial clustering of sex exchange behavior as well as norms, and identified a housing complex with the highest density of exchange sex. Duncan et al. [36] examined the concept of spatial polygamy, the ways individual move across and experience multiple neighborhood contexts, and noted that young MSM who reported concordance among their residential, socializing and sex neighborhoods were more likely to report recent engagement in condomless oral sex. Raymond et al. [37] found that Black MSM and transwomen were more likely to live in high HIV prevalence, low income areas, and that increasing neighborhood HIV prevalence was associated with an increase in the number of potentially serodiscordant unprotected sex acts.

Subjective Measurements

Lower perceived neighborhood condition among residents was consistently associated with more drug use and sexual risk behavior in seventeen studies. Twelve studies identified a relationship between poorer perceived neighborhood quality and increased sexual risks [7, 13, 20, 38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Perceived neighborhood social disorder (e.g., perpetuation of violence) was consistently associated transactional sex [13, 38, 46], STIs [7], having higher risk partners [20, 41], unprotected intercourse [40, 42], number of partners [43], and other indicators of sexual risk (i.e., sex while using drugs) [45].

Drug Risk and HIV Vulnerability

Six studies identified a relationship between living in a more disadvantaged neighborhood and increased HIV vulnerability due to drug risks [47,48,49,50,51,52]. Four studies indicated that individuals in more disadvantaged neighborhoods had less access to harm reduction services [50] and drug treatment [47, 49, 51]. Two studies found that lower socioeconomic status of neighborhoods was associated with increased drug use, particularly injection drugs [48, 52]. Contrasting these studies, one study of street recruited injection drug users found that residing in a census tract with concentrated poverty was associated with less syringe sharing; this was true for those who most often slept in concentrated poverty tracts, while those with more transient residence experienced increased odds in syringe sharing [53]. Another study also noted increases in injection drug use as residential segregation increased [54]. With findings from qualitative interviews with female drug users, Sterk et al. [55] interpreted the data to indicate that a neighborhood’s physical and social infrastructure could lead to alienation, in turn negatively affecting behavior change efforts, while social capital and social support could mediate these negative effects.

Sexual Risk Behaviors and HIV Vulnerability

Seven studies examined the relationship between objective measures of neighborhood-level factors and sexual risks behavior. Living in a more disadvantaged neighborhood was associated with inconsistent condom use [25, 56, 57]. However, findings regarding anal intercourse were mixed as one study identified an inverse relationship between neighborhood condition and anal sex [34] while another detected a direct relationship [57]. Young MSM in neighborhoods with greater disadvantage (e.g., percentage of households in poverty) were less likely to report serodiscordant partners [58]. Further, areas with fewer people completing high school contained individuals more likely to engage in transactional sex [6]. In cities with high levels of both poverty and Black residents, there were higher reports of men who have sex with men and women, and more heterosexual female HIV cases [59].

Six studies highlighted social determinants (e.g., lack of sexual health support services, lack of activities for young people, mass incarceration, poverty, neighborhood segregation) that restrict the types of individuals in one’s social/sexual networks, impair access to HIV prevention tools (e.g., condoms, PrEP), impact community norms about drug use and sexual behaviors, and foster HIV risk behaviors [44, 60,61,62,63,64]. Several multi-level pathways were identified between neighborhood quality and HIV vulnerability. Neighborhood condition affects sexual risks indirectly through psychological distress and substance use [39, 41]. Geographic restrictions constrain selection pools [62] and racial residential segregation concentrates African Americans in areas of higher HIV prevalence [8]. Among women, an imbalance of male partners increases HIV vulnerability and neighborhood disadvantage may also exacerbate the necessity of transactional sex [64].

Geographic Distribution of the Reviewed Studies

The majority of the studies were conducted in the Northeast and South regions of the U.S.; few took place in the Midwest or West (see Fig. 2). The Northeast and South have historically been hit hardest by the HIV epidemic, thus it is logical for more studies to be conducted in those areas. However, given HIV incidence and prevalence in the West, there were fewer studies conducted than anticipated. In all regions, studies tended to take place in large urban centers, with many studies concentrated in the New York-Washington, D.C. corridor. However, several populous metropolitan areas, including Dallas, San Antonio, Phoenix, and San Diego, were unstudied in the reviewed literature despite historical HIV incidence and prevalence rates that would warrant further investigation. Further, Nevada, Arizona, Oklahoma, Missouri, Kentucky and Ohio are states/have counties prioritized in the EHE, but were absent from the review. Alabama, Arkansas and South Carolina were only represented by one study each, and several counties were underrepresented in Texas.

Maps of the “Ending the HIV Epidemic” (EHE) jurisdictions (top) (source https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview) and locations of the included studies (bottom). In the bottom map, major cities are denoted with a square; each dot represents a single study

Discussion

In the context of HIV vulnerability, the neighborhoods where people live and/or frequent, and the sexual or substance use behaviors in which they engage while there, matter. Underscoring the importance of healthography [65], the notion that geography and where people live shapes health and well-being, this systematic review affirms the importance of neighborhood-level vulnerabilities for HIV risk. We advance knowledge about the relationship between neighborhoods and risk with five noteworthy contributions.

First, we highlight that neighborhood disadvantage, regardless of whether it is assessed objectively or subjectively, is one of the most robust correlates of HIV risk. Our review indicates that HIV is not randomly distributed in neighborhoods, but instead concentrated in neighborhoods characterized by factors such as high rates of poverty, crime, and abandoned buildings. These forms of neighborhood disadvantage are not naturally occurring. Rather, they are the consequence of laws, policies and practices to maintain racialized inequities such as residential segregation and inequitable urban housing policies (e.g., those that limit access to public housing for people with criminal or incarceration records). Historically, policies such as these have relegated people at the most marginalized intersections of social-structural inequality—people who are racial/ethnic minority, poor, immigrants and undocumented, those addicted to substances—to predominantly poor urban and rural neighborhoods characterized by risk factors (e.g., substance use, sexual networks with dense HIV concentration). This increases HIV vulnerability. This finding has important implications for structural interventions, namely local, state and federal initiatives to increase affordable housing and housing stability for low-income people. Building on evidence that stable housing programs are effective in improving HIV outcomes (e.g., Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS [HOPWA]) [66], it stands to reason that similar housing and neighborhood improvement programs at the population level could also be leveraged as an HIV prevention strategy.

Second, we illustrate key gaps in neighborhood and HIV prevention research. Although the Food and Drug Administration approved PrEP as an effective biomedical HIV intervention tool in 2012, and PrEP is included as a key pillar in the HIV Prevention Continuum, we found no studies in the 2007 to 2017 review period focused on neighborhood-level effects on PrEP uptake. There remains a critical need for research in this area; newer findings document PrEP access disparities among people from high poverty neighborhoods [67]. There is also a paucity of research with youth and transgender persons, and racial/ethnic diversity is lacking (i.e., only one study focused on Latinx populations). This highlights opportunities for research and interventions to expand HIV prevention services for diverse groups of people who live in or frequent disadvantaged neighborhoods. Specifically, it suggests that HIV/AIDS services organizations should adopt or expand mobile outreach units to deliver HIV prevention services such as HIV testing, condom distribution, and PrEP access to people in neighborhoods at increased HIV risk. Such a neighborhood-based approach to HIV prevention could provide an effective remedy to some of the barriers to HIV prevention services (e.g., lack of public transportation, limited childcare options).

Third, our findings underscore methodological and data-related barriers to advancing the science of neighborhood-level effects on HIV-related outcomes. There is no standardized way to define neighborhoods, and best practices to generate and analyze data on the relationship between neighborhoods and HIV vulnerability are lacking. This hinders our ability to fully understand the role of neighborhoods in HIV vulnerability, as well as to implement interventions to mitigate the negative effects. Novel partnerships are needed among health departments, community-based organizations, academic institutions and others to collect and organize data across multiple levels for more nuanced analyses. Given prior critiques, it will be important to account for residential and nonresidential exposures in such work to avoid confounding effects from the places people visit over time [68]. Additionally, while diverse theoretical approaches were applied in the reviewed studies (e.g., ecology-oriented theories), most of the research used the same frameworks. There remains a need to apply, and even develop, theories that account for the mediating role of factors such as the intersectional identities of neighborhood residents, unintended consequences of spatialized policies (e.g., drug reform and targeting of racial and other minoritized communities) and resource availability in the relationship between HIV vulnerability and neighborhood context. This will contribute to the generation of theory driven hypotheses to clearly articulate how neighborhoods are linked to this key outcome [69].

Our assessment of geographical distribution is the fourth noteworthy contribution. Our analyses indicate that the majority of the counties/states identified in the EHE were represented in the studies included in this review (89%, n = 51). However, there were considerable gaps with underrepresentation of research in highly affected rural areas and Southern states. This key knowledge can be used to set future research priorities and allocate resources to underserved communities. Such priority setting is increasingly important given intersections among healthography, structural injustice (e.g., inequitable drug policies, over-policing) and HIV-related outcomes. For example, communities with higher rates of mass incarceration demonstrate elevated HIV rates [70]. Thus, actions within the criminal justice system may increase HIV vulnerability in neighborhoods. Specifically, the War on Drugs and “get tough on crime” policies from the late twentieth century may impact neighborhood viability and subsequently facilitate elevated HIV vulnerability, particularly in Black communities. These policies foster over-policing in Black communities [71]. Coupled with harsher charges (often for similar crimes as White people) and sentencing disparities, this approach to criminal justice has helped facilitate the large scale removal of many Black people, particularly Black men, from their homes and communities [71]. This increases HIV vulnerability through several pathways including alteration of sexual networks (e.g., monogamy interruption, imbalanced sex ratio) and the downstream deleterious impacts on intimate relationship dynamics (e.g., condom negotiation, negotiation against sexual concurrency) [72]. Moreover, the increased risk for economic disenfranchisement and undermined access to HIV prevention resources following incarceration further increases HIV vulnerability [72].

Lastly, our work aligns with mounting advocacy to jettison the socially constructed concept of “race” as an explanatory variable for health inequities such as HIV—and now COVID-19—that disproportionately affect Black, Latinx, Indigenous and other racial/ethnic minority communities. Instead, we must emphasize the role of structural injustice based on race in constraining the ability of people in disadvantaged and impoverished neighborhoods to protect themselves from HIV compared with people who inhabit resource and income-rich neighborhoods. Applied to our focus on neighborhoods and HIV vulnerability, the historical legacy of structural racism affects virtually every aspect of where Black people live in the U.S., and in turn their HIV ulnerability, access to HIV prevention services, and even HIV viral suppression [73, 74]. Indeed, there is now ample empirical evidence that people in diverse Black communities (e.g., young heterosexual adults; gay, bisexual and other MSM) are at disproportionate risk for HIV despite engaging in fewer sexual and substance use risk behaviors than their White counterparts [75,76,77]. Assessing risk at the neighborhood level underscores that many racial differences in HIV incidence and prevalence reflect shared experiences of oppression structured by race (e.g., residential segregation), not genetic or biological predispositions to HIV. This knowledge is promising, because it lays a foundation for the field to prioritize factors that are modifiable. This supports the development and implementation of multilevel interventions, such as simultaneously providing comprehensive individual education and enacting policies to desegregate communities and reduce neighborhood poverty concentration [4]. Ultimately, such an approach will address the neighborhood-level structural inequities that increase HIV risk—rather than continue to reify the intractability of inequality by highlighting factors (i.e., “race”) that are in essence, immutable [78].

Limitations

This review examined articles from 2007 through 2017 in a proscribed set of databases. While a substantive number of studies were included in the review, we missed related papers published outside of this window. With the focus narrowed to HIV risk behaviors, we are unable to provide implications for other highly relevant HIV outcomes (e.g., medication adherence). However, this more focused approach allowed us to provide richer insights on behavior, and the methods can be replicated to examine additional relevant outcomes.

Conclusion

We spotlight neighborhoods as a critical context for understanding HIV vulnerability above and beyond the exclusively individual-level that has conventionally characterized most social and behavioral HIV prevention research. Our findings underscore a need to challenge solely individualistic explanations for HIV risk behaviors, in favor of a more expansive structural approach, focused on neighborhood-level influences. Conversely, more research is also needed to advance knowledge and interventions about the neighborhood-level factors that are protective, particularly in poor and under-resourced neighborhoods (e.g., initiatives designed to foster social cohesion). As for HIV prevention and other health equity researchers, our findings underscore a need for structural competency. Albeit developed primarily for clinical trainees, the structural competency paradigm has applied utility for those who conduct HIV prevention research and design interventions and policy. The structural competency approach proposes five steps to increase knowledge about how “… the organization of institutions and policies, as well as of neighborhoods and cities…” (p. 127) determine health [79]. Greater attention to understanding and developing interventions to address which particular aspects of neighborhoods increase and reduce HIV risk, how, and for whom (i.e., key intersections of race, gender, class, sexual and gender minority status, and/or immigration status), will likely hold greater promise for meeting the goals of the EHE than continuing to ignore the role of neighborhoods in increasing HIV vulnerability.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States and Dependent Areas 2019 [cited 2020 February 6]. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics/overview/cdc-hiv-us-ataglance.pdf.

Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21(15):2083.

Brawner BM. A multilevel understanding of HIV/AIDS disease burden among African American women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43(5):633–43.

Smedley BD. Multilevel interventions to undo the health consequences of racism: the need for comprehensive approaches. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2019;25(1):123–5.

Meijer M, Röhl J, Bloomfield K, Grittner U. Do neighborhoods affect individual mortality? A systematic review and meta-analysis of multilevel studies. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(8):1204–12.

Stevens R, Icard L, Jemmott JB, O’Leary A, Rutledge S, Hsu J, et al. Risky trade: individual and neighborhood-level socio-demographics associated with transactional sex among urban African American MSM. J Urban Health. 2017;94(5):676–82.

Kerr JC, Valois RF, Siddiqi A, Vanable P, Carey MP. Neighborhood condition and geographic locale in assessing HIV/STI risk among African American adolescents. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(6):1005–13.

Brawner BM, Guthrie B, Stevens R, Taylor L, Eberhart M, Schensul JJ. Place still matters: racial/ethnic and geographic disparities in HIV transmission and disease burden. J Urban Health. 2017;94(5):716–29.

Latkin CA, German D, Vlahov D, Galea S. Neighborhoods and HIV: a social ecological approach to prevention and care. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):210–24.

Wilson PA, Nanin J, Amesty S, Wallace S, Cherenack EM, Fullilove R. Using syndemic theory to understand vulnerability to HIV infection among Black and Latino men in New York City. J Urban Health. 2014;91(5):983–98.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. J Am Med Assoc. 2019;321(9):844–5.

Parrado EA, Flippen C. Community attachment, neighborhood context, and sex worker use among Hispanic migrants in Durham, North Carolina, USA. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(7):1059–69.

Akers AY, Muhammad MR, Corbie-Smith G. “When you got nothing to do, you do somebody”: a community’s perceptions of neighborhood effects on adolescent sexual behaviors. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2011;72(1):91–9.

Buttram ME, Kurtz SP. Risk and protective factors associated with gay neighborhood residence. Am J Mens Health. 2013;7(2):110–8.

Braine N, Acker C, Goldblatt C, Yi H, Friedman S, Desjarlais DC. Neighborhood history as a factor shaping syringe distribution networks among drug users at a U.S. Syringe Exchange. Soc Netw. 2008;30(3):235–46.

Egan JE, Frye V, Kurtz SP, Latkin C, Chen M, Tobin K, et al. Migration, neighborhoods, and networks: approaches to understanding how urban environmental conditions affect syndemic adverse health outcomes among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(Suppl 1):S35-50.

Gindi RM, Sifakis F, Sherman SG, Towe VL, Flynn C, Zenilman JM. The geography of heterosexual partnerships in Baltimore city adults. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(4):260–6.

Tobin KE, Latkin CA, Curriero FC. An examination of places where African American men who have sex with men (MSM) use drugs/drink alcohol: a focus on social and spatial characteristics. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):591–7.

Cooper HLF, Linton S, Haley DF, Kelley ME, Dauria EF, Karnes CC, et al. Changes in exposure to neighborhood characteristics are associated with sexual network characteristics in a cohort of adults relocating from public housing. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(6):1016–30.

Rudolph AE, Crawford ND, Latkin C, Fowler JH, Fuller CM. Individual and neighborhood correlates of membership in drug using networks with a higher prevalence of HIV in New York City (2006–2009). Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23(5):267–74.

Buot M-LG, Docena JP, Ratemo BK, Bittner MJ, Burlew JT, Nuritdinov AR, et al. Beyond race and place: distal sociological determinants of HIV disparities. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e91711.

Mustanski B, Birkett M, Kuhns LM, Latkin CA, Muth SQ. The role of geographic and network factors in racial disparities in HIV among young men who have sex with men: an egocentric network study. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(6):1037–47.

Rothenberg RB, Dai D, Adams MA, Heath JW. The Human immunodeficiency virus endemic: maintaining disease transmission in at-risk urban areas. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(2):71–8.

Frye V, Nandi V, Egan JE, Cerda M, Rundle A, Quinn JW, et al. Associations among neighborhood characteristics and sexual risk behavior among Black and White MSM living in a major urban area. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(3):870–90.

Bluthenthal RN, Do DP, Finch B, Martinez A, Edlin BR, Kral AH. Community characteristics associated with HIV risk among injection drug users in the San Francisco Bay Area: a multilevel analysis. J Urban Health. 2007;84(5):653–66.

Lutfi K, Trepka MJ, Fennie KP, Ibanez G, Gladwin H. Racial residential segregation and risky sexual behavior among non-Hispanic blacks, 2006–2010. Soc Sci Med. 2015;140:95.

Biello KB, Niccolai L, Kershaw TS, Lin H, Ickovics J. Residential racial segregation and racial differences in sexual behaviours: an 11-year longitudinal study of sexual risk of adolescents transitioning to adulthood. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(1):28–34.

Knittel AK, Snow RC, Riolo RL, Griffith DM, Morenoff J. Modeling the community-level effects of male incarceration on the sexual partnerships of men and women. Soc Sci Med. 2015;147:270–9.

Neaigus A, Jenness SM, Reilly KH, Youm Y, Hagan H, Wendel T, et al. Community sexual bridging among heterosexuals at high-risk of HIV in New York City. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(4):722–36.

Pachankis JE, Eldahan AI, Golub SA. New to New York: ecological and psychological predictors of health among recently arrived young adult gay and bisexual urban migrants. Ann Behav Med. 2016;50(5):692–703.

Egan JE, Frye V, Kurtz SP, Latkin C, Chen M, Tobin K, et al. Migration, neighborhoods, and networks: approaches to understanding how urban environmental conditions affect syndemic adverse health outcomes among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:S50.

Kelly BC, Carpiano RM, Easterbrook A, Parsons JT. Sex and the community: the implications of neighbourhoods and social networks for sexual risk behaviours among urban gay men. Sociol Health Illn. 2012;34(7):1085–102.

Frye V, Koblin B, Chin J, Beard J, Blaney S, Halkitis P, et al. Neighborhood-level correlates of consistent condom use among men who have sex with men: a multi-level analysis. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(4):974–85.

Tobin KE, Hester L, Davey-Rothwell MA, Latkin CA. An examination of spatial concentrations of sex exchange and sex exchange norms among drug users in Baltimore, Maryland. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 2012;102(5):1058–66.

Duncan DT, Kapadia F, Halkitis PN. Examination of spatial polygamy among young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in New York City: the P18 Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(9):8962–83.

Raymond HF, Chen YH, Syme SL, Catalano R, Hutson MA, McFarland W. The role of individual and neighborhood factors: HIV acquisition risk among high-risk populations in San Francisco. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):346–56.

Bobashev GV, Zule WA, Osilla KC, Kline TL, Wechsberg WM. Transactional sex among men and women in the south at high risk for HIV and other STIs. J Urban Health. 2009;86(1):32–47.

Bowleg L, Neilands TB, Tabb LP, Burkholder GJ, Malebranche DJ, Tschann JM. Neighborhood context and Black heterosexual men’s sexual HIV risk behaviors. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(11):2207–18.

DePadilla L, Elifson KW, Sterk CE. Beyond sexual partnerships: the lack of condom use during vaginal sex with steady partners. Int Public Health J. 2012;4(4):435–46.

Latkin CA, Curry AD, Hua W, Davey MA. Direct and indirect associations of neighborhood disorder with drug use and high-risk—sexual partners. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(6):S241.

Quinn K, Voisin DR, Bouris A, Schneider J. Psychological distress, drug use, sexual risks and medication adherence among young HIV-positive Black men who have sex with men: exposure to community violence matters. AIDS Care. 2016;28(7):866–72.

Senn TE, Walsh JL, Carey MP. Mediators of the relation between community violence and sexual risk behavior among adults attending a public sexually transmitted infection clinic. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45(5):1069–82.

Stevens R, Gilliard-Matthews S, Nilsen M, Malven E, Dunaev J. Socioecological factors in sexual decision making among urban girls and young women. Jognn. 2014;43(5):644–54.

Voisin DR, Hotton AL, Neilands TB. Testing pathways linking exposure to community violence and sexual behaviors among African American youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43(9):1513–26.

Rudolph AE, Linton S, Dyer TP, Latkin C. Individual, network, and neighborhood correlates of exchange sex among female non-injection drug users in Baltimore, MD (2005–2007). AIDS Behav. 2013;17(2):598–611.

Cooper HL, Linton S, Kelley ME, Ross Z, Wolfe ME, Chen Y-T, et al. Racialized risk environments in a large sample of people who inject drugs in the United States. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2016;27:43–55.

Crawford ND, Borrell LN, Galea S, Ford C, Latkin C, Fuller CM. The Influence of neighborhood characteristics on the relationship between discrimination and increased drug-using social ties among illicit drug users. J Community Health. 2013;38(2):328–37.

Genberg BL, Gange SJ, Go VF, Celentano DD, Kirk GD, Latkin CA, et al. The effect of neighborhood deprivation and residential relocation on long-term injection cessation among injection drug users (IDUs) in Baltimore, Maryland. Addiction. 2011;106(11):1966–74.

Heimer R, Barbour R, Palacios WR, Nichols LG, Grau LE. Associations between injection risk and community disadvantage among suburban injection drug users in Southwestern Connecticut, USA. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(3):452–63.

Nandi A, Glass TA, Cole SR, Chu H, Galea S, Celentano DD, et al. Neighborhood poverty and injection cessation in a sample of injection drug users. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(4):391–8.

Williams CT, Latkin CA. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, personal network attributes, and use of heroin and cocaine. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(6):S203–10.

Martinez AN, Lorvick J, Kral AH. Activity spaces among injection drug users in San Francisco. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):516–24.

Cooper HLF, Friedman SR, Tempalski B, Friedman R. Residential segregation and injection drug use prevalences among Black adults in US metropolitan areas. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(2):344–52.

Sterk CE, Elifson KW, Theall KP. Individual action and community context: the health intervention project. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(6):S181.

Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA, Caldwell CH. Neighborhood disadvantage and changes in condom use among African American adolescents. J Urban Health. 2011;88(1):66–83.

Haley DF, Haardorfer R, Kramer MR, Adimora AA, Wingood GM, Goswami ND, et al. Associations between neighborhood characteristics and sexual risk behaviors among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in the southern United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(4):252–9.

Bauermeister JA, Eaton L, Andrzejewski J, Loveluck J, VanHemert W, Pingel ES. Where you live matters: structural correlates of HIV risk behavior among young men who have sex with men in metro Detroit. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(12):2358–69.

Raymond HF, Al-Tayyib A, Neaigus A, Reilly KH, Braunstein S, Brady KA, et al. HIV among MSM and heterosexual women in the United States: an ecologic analysis. JAIDS. 2017;75:S280.

Akers AY, Muhammad MR, Corbie-Smith G. “When you got nothing to do, you do somebody”: a community’s perceptions of neighborhood effects on adolescent sexual behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(1):91–9.

Boyer CB, Greenberg L, Chutuape K, Walker B, Monte D, Kirk J, et al. Exchange of sex for drugs or money in adolescents and young adults: an examination of sociodemographic factors, hiv-related risk, and community context. J Community Health. 2017;42(1):90–100.

Brawner BM, Reason JL, Hanlon K, Guthrie B, Schensul JJ. Stakeholder conceptualisation of multi-level HIV and AIDS determinants in a Black epicentre. Cult Health Sex. 2017;19(9):948–63.

Cené CW, Akers AY, Lloyd SW, Albritton T, Powell Hammond W, Corbie-Smith G. Understanding social capital and HIV risk in rural African American communities. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(7):737–44.

Frew PM, Parker K, Vo L, Haley D, O’Leary A, Diallo DD, et al. Socioecological factors influencing women’s HIV risk in the United States: qualitative findings from the women’s HIV SeroIncidence study (HPTN 064). BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):803.

Greenberg MR. Healthography. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2022.

Wolitski RJ, Kidder DP, Pals SL, Royal S, Aidala A, Stall R, et al. Randomized trial of the effects of housing assistance on the health and risk behaviors of homeless and unstably housed people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):493–503.

Salcuni P, Smolen J, Jain S, Myers J, Edelstein Z. Trends and associations with PrEP prescription among 602 New York City (NYC) ambulatory care practices, 2014–2016. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(suppl_1):S21-S.

Chaix B, Duncan D, Vallée J, Vernez-Moudon A, Benmarhnia T, Kestens Y. The, “residential” effect fallacy in neighborhood and health studies. Epidemiology. 2017;28(6):789–97.

Bishop AS, Walker SC, Herting JR, Hill KG. Neighborhoods and health during the transition to adulthood: a scoping review. Health Place. 2020;63:102336.

Ojikutu BO, Srinivasan S, Bogart LM, Subramanian S, Mayer KH. Mass incarceration and the impact of prison release on HIV diagnoses in the US South. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(6):e0198258.

Alexander M. The New Jim Crow. New York, NY: The New Press; 2011.

Kerr J, Jackson T. Stigma, sexual risks, and the war on drugs: examining drug policy and HIV/AIDS inequities among African Americans using the Drug War HIV/AIDS Inequities Model. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;37:31–41.

Khazanchi R, Sayles H, Bares SH, Swindells S, Marcelin JR. Neighborhood deprivation and racial/ethnic disparities in HIV viral suppression: a single-center cross-sectional study in the U.S. midwest. Clinical Infect Dis. 2020

Olatosi B, Weissman S, Zhang J, Chen S, Haider MR, Li X. Neighborhood matters: impact on time living with detectable viral load for new adult HIV diagnoses in South Carolina. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(4):1266–74.

Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, Hart TA, Jeffries WL 4th, Wilson PA, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2012;380(9839):341–8.

Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, Miller WC, Bauer DJ. Sexual and drug behavior patterns and HIV/STD racial disparities: the need for new directions. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1–8.

Kanny D, Jeffries WL, Chapin-Bardales J, Denning P, Cha S, Finlayson T, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in HIV preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men–23 Urban Areas, 2017. Morb Mortal Mon Rep (MMWR). 2019;68(37):801–6.

Bauer GR. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc Sci Med. 2014;110:10–7.

Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126–33.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; grant R25MH087217, Brawner pilot project PI; grant R01 MH100022-02, Bowleg PI). J. A. B. received support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholars Program. S. B. received support from the Rita & Alex Hillman Foundation Hillman Scholars Program in Nursing Innovation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the funding sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study and manuscript writing. BMB and JK conceptualized and lead the study. RJ created the reference library for data management and independently screened titles and abstracts to identify full-text articles for final eligibility review. BFC and JAB conducted data extraction based on a protocol for key study characteristics. SB created maps to visualize the geographic distribution of the studies. RS and LB reviewed and edited manuscript drafts.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brawner, B.M., Kerr, J., Castle, B.F. et al. A Systematic Review of Neighborhood-Level Influences on HIV Vulnerability. AIDS Behav 26, 874–934 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03448-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03448-w