Abstract

Introduction

The study investigates the emotional discomfort of cancer patients and their caregivers, who need to access the oncology day hospital to receive treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy.

Methods

This is a single-institution, prospective, cross-sectional study. From May to June 2020, the points of view of both patients and caregivers were compared through 2 different multiple-choice questionnaires, enquiring demographic characteristics, changes in emotional status, interpersonal relationships with health professionals (HCPs) and self-perception of treatment outcomes.

Results

Six hundred twenty-five patients and 254 caregivers were enrolled. Females were prevalent and patients were generally older than caregivers. Forty percent of patients and 25.6% of caregivers thought they were at a greater risk of contagion because lived together with a cancer patient or accessed the hospital. Both patients (86.3%) and caregivers (85.4%) considered containment measures a valid support to avoid the spread of infection. People with a lower education level were less worried about being infected with SARS-COV-2. Waiting and performing visits/treatments without caregivers had no impact on the emotional status of patients (64.4%), but generated in caregivers greater anxiety (58.8%) and fear (19.8%) of not properly managing patients at home. The majority of patients (54%) and caregivers (39.4%) thought the pandemic does not influence treatment outcomes. The relationship with HCPs was not negatively impacted for majority of patients and caregivers.

Conclusions

Starting from these data, we can better understand the current psychological distress of patients and their families in order to develop potential strategies to support them in this strenuous period of crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In February 2020, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak swept Italy. To prevent the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 infection, starting from March 9th, the Italian Government progressively introduced mitigation measures that drastically limited social interactions [1].

The “lockdown” led to substantial changes in people’s lifestyles with a consequent negative impact on their psychological well-being. The limitations in daily activities, the social isolation combined with the fear of contracting the infection and the uncertainties related to this new and unexpected condition have generated insecurity, anxiety and emotional distress [2]. Healthcare professionals (HCPs), who were on the frontline fighting the pandemic, have been one of the most physically and emotionally involved category [3]. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a reorganization of the Healthcare System, in particular for those people who needed to continue “life-saving” treatments, as in the case of cancer patients.

An important goal for the oncologist is to guarantee the continuum of care for cancer patients, even during a period of sanitary crisis, despite the potential risk of COVID-19 infection. Delaying treatment of metastatic cancer patients can lead to disease progression, performance status deterioration and worsening of symptoms. On the other hand, the omission or delay of adjuvant therapies can increase mortality. The main International Societies of Oncology have issued recommendations aimed to mitigate the negative effects of COVID-19 pandemic on diagnosis and treatment of cancer patients [4,5,6,7,8].

First of all, they recommended making a correct patient selection, categorising them into high, medium or low priority, in order to minimize hospital access for those patients who could continue the treatment/surveillance while staying at home through online medical counselling (telemedicine) or home drug delivery. For outpatients who needed to access the hospital, it was crucial to adopt all procedures aimed to reduce the risk of potential contagion, through a correct triage at the entrance of the day hospital and clinic, the use of individual protection devices and a reorganization of spaces in order to maintain social distancing [9]. The implementation of these procedures led to the unavoidable consequence that patients accessed the hospital without caregivers, who could not stay with them in the waiting room and during the visit. All the activities (visits and therapy administration) took place in a new and unusual way, which could destabilize the already fragile emotional balance of patients but also of their caregivers. During the pandemic, because of the strict social isolation and the travel limitation (including the use of public means of transport), caregivers could no longer share the burden of taking care of patients with others (friends or support groups) and this situation had enhanced the psychological, economic and practical burden of caregivers. Some surveys on patients’ insights were conducted but to date, just very few data are available about a direct comparison of patients and caregivers’ opinions on these topics [10].

The aim of our study is to evaluate how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted on the emotional approach to therapeutic path of cancer outpatients and their caregivers and to compare the points of view of both patients and caregivers about this topic. Investigating these aspects is important in order to understand the difficulties that cancer patients and their families are facing during this health crisis, and to develop adequate strategies to deal with them.

Materials and methods

This is a single-institution, prospective, cross-sectional study of the Department of Oncology at Luigi Sacco Hospital, one of the Italian hospitals which was mostly involved in the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey was conducted on outpatients who were receiving active cancer treatment and their caregivers. Data collection was performed from 5 May to 5 June 2020. We devised two different multiple-choice questionnaires (15 questions for patients and 17 for caregivers) enquiring about demographic characteristics, changes in emotional status, interpersonal relationships with health professionals (HCPs) and self-perception of treatment outcomes. The answers could be “Yes”, “No”, “I don’t know” and “Enough” (Enough = the responder partially agrees with the statement formulated in the question).

Statistical methods

The answers were categorized into two groups: “Yes” and “Enough” versus “No”. If the proportion of subjects answering “I don’t know” was higher than 5% in patients’ questionnaires and 10% in caregivers’ questionnaires, the impact of the demographic characteristics on the answer “I don’t know” was investigated. Differences in the answers to questions in both patients and caregivers questionnaires were investigated by chi-squared test. Details on the matching of questions in the two questionnaires are provided in Table 1.

We also evaluated the impact of demographic characteristics on the answers to each question, which was investigated by univariable and multivariable logistic regression models. Results were expressed in terms of odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were carried out using SAS statistical software (version 9.4).

Results

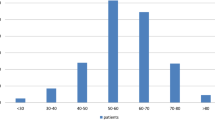

Six hundred twenty-five consecutive patients and 254 caregivers were enrolled. The whole population was mainly made up of females: 407 (65.1%) patients and 143 (56.3%) caregivers were females. Patients were generally older than caregivers: 436 (69.8%) were > 60 years while the majority of caregivers were 41–60 years old (128, 50.4%) (p < 0.001). Moreover, 315 (50.5%) patients had a low education level (primary and secondary school) while 170 (67.5%) caregivers had a higher degree (high school or greater) (p < 0.001). All the demographic characteristics of patients and caregivers are reported in Table 2.

About half of the patients (330, 52.8%) reached the hospital with their own caregivers, who were usually a son/daughter (104, 40.9%) or the partner (97, 38.2%), and frequently lived together (148, 58.3%). The answers of patients’ and caregivers’ questionnaires are reported in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Comparison between patients and caregivers

Table 5 reports the comparison between patients and caregivers’ answers (see Table 1 for details on matching questions).

About half of the cancer patients felt more vulnerable to COVID-19 compared to their caregivers (question P1: 250, 52.5%). Patients were more worried than caregivers about the risk of exposing cohabiting people to the COVID-19 infection because of their frequent access to the hospital (question P4 and question C2: yes/enough 117 [25.1%] vs. 32 [14.7%], p = 0.002).

Both patients and caregivers considered the containment measures (triage at the entrance, social distancing, personal protective equipment) a valid support to avoid the spread of infection (question P2 and C3: 538 [92.0%] vs 217 [88.9%] respectively, p = 0.163). Both patients and caregivers believed that the containment measures did not involve an excessive expenditure of time, with a major prevalence of positive judgments in caregivers compared to patients (questions P3 and C4: 489 [85.9%] vs. 225 [91.5%] p = 0.028).

A personal emotional change caused by waiting and performing visits and treatments without caregivers was reported more by caregivers (158, 66.1%) than by patients (195, 32.7%) (questions P6 and C6, p < 0.001). Specifically, 77 (58.8%) caregivers reported greater anxiety and 26 (19.8%) had a fear of not managing the patients properly at home (question C7). Moreover, caregivers thought that the pandemic caused a negative impact on the emotional state of the patients more than what the patients themselves stated (questions P6 and C5: 195 [32.7%] vs 155 [66.5%], p < 0.001).

The majority of patients (336, 73.2%) and caregivers (100, 62.1%) thought that the pandemic did not influence treatment outcomes, with a higher prevalence of positive answers in patients (questions P8 and C9, p = 0.008). The relationship with HCPs was not negatively affected for both patients (question P5: 457, 79.6%) and caregivers (question C8:167, 94.9%), but about a quarter of patients and caregivers thought that the attention of HCPs was more focused on COVID-19 than on cancer treatment (questions P9 and C10: 119 [25.0%] vs. 45 [29.2%], p = 0.300).

Impact of patients’ characteristics on answers

The results of logistic regression analyses on patients’ questionnaires are summarized in Table 6a, b, and c in the supplementary file.

No statistically significant associations were found between age and sex and the answers to questions, although males were more likely to answer “I don’t know” to the questions concerning the time spent for the triage and application of safety standards (question P3: adjusted OR [aOR] 1.78, 95%CI 1.01–3.15, p = 0.047, online table S1). Compared to patients with a lower education level, those with an upper secondary school degree were more likely to think that cohabiting people were more exposed to COVID-19 infection due to their frequent access to the hospital (question P4: aOR 2.18, 95%CI 1.08–4.41, p = 0.030) and to declare a possible negative effect of the pandemic on their treatment (question P8: aOR 2.35, 95%CI 1.11–4.99, p = 0.025). Moreover, patients with an upper secondary school degree were more likely to think that the attention of doctors was more focused on COVID-19 than on cancer treatment (question P9: aOR 2.60, 95%CI 1.28–5.28, p = 0.009). In regards to the possibility of receiving “I don’t know” as an answer, patients with a primary school degree had more difficulty in answering several questions (online table S1).

Moreover, patients who accessed the hospital for a visit were less likely to think they had a higher risk of contagion compared to patients who accessed it for the therapy (question P1: aOR 0.45, 95%CI 0.30–0.69,p < 0.001) and they were more likely to answer “I don’t know” to the same question (aOR 2.12, 95%CI 1.32–3.40,p = 0.002); more frequently, they thought that the application of safety procedures had changed the relationship with HCPs and that the attention of doctors was more focused on COVID-19 (question P5: aOR 1.86, 95%CI 1.12–3.09, p = 0.016; question P9: aOR 1.96, 95%CI 1.17–3.25, p = 0.010 respectively). Finally, they were more likely to answer “I don’t know” to this last question (question P9: aOR 1.76,95%CI 1.12–2.77, p = 0.015).

Impact of caregivers’ characteristics on answers

The results of logistic regression analyses on caregivers’ questionnaires are summarized in Table 7a, b, and c in the supplementary file.

No statistically significant associations were found between the answers and the demographic characteristics, except for sex and education level. Compared to female caregivers, males were less likely to believe in a negative effect of the pandemic on patients’ treatment (question C9: aOR 0.48, 95%CI 0.24–0.96, p = 0.039).

Compared to caregivers with a low education level, caregivers with a higher education level were more likely to think they were at a greater risk of contagion because they were accompanying (question C1: caregivers with upper secondary school degree: aOR 2.56, 95%CI 1.12–5.86, p = 0.026; caregivers with higher school degree: aOR 3.11, 95%CI 1.17–8.26, p = 0.023) or cohabiting with the patients (question C2: caregivers with upper secondary school degree: aOR 4.48, 95%CI 1.24–16.2, p = 0.022; caregivers with higher school degree: aOR 4.54, 95%CI 1.06–19.5, p = 0.042).

As for patients, some caregivers had difficulty in answering the questions and checked the “I don’t know” option. More details are available in online Table S2.

Discussion

This is the first Italian survey aimed to investigate the emotional approach to the care of cancer outpatients and their caregivers, who needed to access the day hospital and clinic of the Department of Oncology during the pandemic. With this study, we wanted to collect the points of view of both the “players” to compare them and evaluate differences and points of agreement, in order to identify the most suitable strategies to support patients and their families in this strenuous period of crisis.

We enrolled a large number of patients in only 1 month and these data reflect the attention of our cancer centre to the continuum of care and the participants’ involvement in this topic. Enrolled patients were mostly female, aged > 60 years old and with a low education level, while caregivers were usually younger, female and with a higher education level. About half of the patients reached the hospital with their own caregivers; however, the number of questionnaires filled in by caregivers was lower (77% of caregivers who accompanied patients to the hospital), probably because a part of them delivered patients to the hospital without accessing the cancer centre to avoid the potential risk of contagion.

What emerges from our survey is that the majority of patients felt more vulnerable to the SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to caregivers; this perception is coherent with the news reported by mass media, drawn from the scientific literature. The first data about COVID-19 in cancer patients were published by Liang and colleagues in March 2020: in their cohort of 1590 COVID-19 positive Chinese patients, 18 had a history of cancer. The authors found that cancer patients had a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 because of their systemic immunosuppression and had a poorer prognosis than those without cancer [11]. Zang et al. retrospectively studied the clinical features of 28 COVID-19-positive cancer patients from three hospitals in Wuhan: they observed that 15 (53.6%) patients developed severe events with a mortality rate of 28.6%, confirming that cancer patients presented a poor outcome with a high occurrence of clinically severe events and a high mortality [12]. The TERAVOLT study also confirmed the high mortality rate (33%) and low admission rate to intensive care units in patients with thoracic cancer [13].

Differently from patients, caregivers did not feel more exposed to infection although they were involved in taking care of someone who was undergoing active cancer treatment. This occurred even if they lived together with patients and needed to access the hospital for the patients’ treatment. Probably, caregivers did not feel more exposed to COVID-19 because they were generally in good general condition, with no significant comorbidity and on average younger than the patient.

Beyond this difference, we found that the education level influenced the perception of the risk of contagion: a higher education level probably led the person to gather more information about the pandemic and to a greater awareness of the severity of the health crisis, causing greater apprehension for their own safety. On the other hand, both patients and caregivers with a low education level were more likely to answer “I don’t know” to the question investigating this setting. These data are consistent with a previous survey aimed to analyse the different levels of risk perception in various populations during a health crisis, and the relative factors that influenced them [14, 15].

Regardless of the perceived risk of contagion, study participants appreciated the application of general risk prevention and mitigation measures, as reported in literature [16].

Caregivers were particularly worried about the psychological well-being of their relatives: they believed that the patients’ concern about the pandemic and the feelings of loneliness during the visit/therapy might add up to the apprehension for the disease and the effort to deal with a complex therapeutic plan. Moreover, since the access of the caregivers to the hospital was limited, patients were alone during the visit and could not share information with the GCs. This situation resulted in the concern of caregivers of not managing the patients properly at home. The most interesting finding of this study was that patients thought that the COVID-19 pandemic would not negatively impact the course of their treatment, the outcome of the therapy and the relationship with HCPs, despite the physical and mental load of their disease. This is probably due to the trust that a patient with a chronic disease has in the people who take care of him [17].

In a subgroup of survey participants, the fear of a “distraction effect” emerged. In fact, in our study we found that patients with a higher education level or patients who accessed the oncology department only occasionally (for example for a visit every 6 months) were concerned because they thought that COVID-19 captured all the HCP’s attention, overshadowing cancer treatment and prevention (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/20/health/treatment-delays-coronavirus.html, https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/news-and-events/blog/cancer-patients-the-forgotten-victims-of-the-covid-19-global-pandemic/, https://www.fightcancer.org/releases/survey-covid-19-affecting-patients%E2%80%99-access-cancer-care) [18].

All the information acquired through this survey allowed us to better understand the emotional changes which occurred in cancer patients and their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Starting from these data, we can develop potential strategies to help them cope better with the current psychological distress. Some suggestions could be for example to enhance online medical counselling (telemedicine) in order to minimize patients’ exposure to COVID-19; to reorganise internal spaces and adopt protective measures also for caregivers to allow them to have access to the visit with the patients in order to gain the necessary information about the patients’ care; to spend time with people who have a lower education level in order to better explain the consequences of the pandemic and the behaviours to adopt to avoid contagion; and to reassure patients and caregivers that the priority of oncologists is cancer care, which is their mission [19,20,21,22].

This study also has limitations. First of all, some selection bias exists due to the voluntary nature of participation. Moreover, even if the number of enrolled subjects is significant for a monocentric study, we have to consider that a number of data has been lost because of the inability of some patients to answer questionnaires (due to performance status, physical or cultural limitations) or the refusal to join the survey both of patients and caregivers. Finally, there is a percentage of particularly apprehensive patients who have postponed visits/therapies and caregivers who prefer not to access in the day hospital for fear of contagion: in these cases, submit the questionnaire was not possible.

To take care of a cancer patient does not only mean to administer therapy but to take care of a whole person, without disregarding the family environment and psychological well-being. Patient-centred care remains the best approach for a successful outcome, even more so during this devastating global pandemic.

Availability of data and material

All data are available in the manuscript and in the supplementary files.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Government of Italy Decree of the president of the Council of Ministers 9 March 2020. March 9, 2020. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/03/09/20A01558/sg. Accessed 10 May 2020

Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Jiang W, Wang H (2020) The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 291:113190

Berardi R, Torniai M, Cona MS, Cecere FL, Chiari R, Guarneri V, La Verde N, Locati L, Lorusso D, Martinelli E, Giannarelli D, Garassino MC, Women for Oncology Italy (2021) Social distress among medical oncologists and other healthcare professionals during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. ESMO Open. 6(2):100053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100053

NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) resources for the cancer care community. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/covid-19/. Accessed 20 Dec 2020

ASCO (American Society of Clinical Oncology). ASCO coronavirus resources. Available from: https://www.asco.org/asco-coronavirus-information. Accessed 20 Dec 2020

ESMO (European Society for Medical Oncology). ESMO COVID-19 and cancer. Available from: https://www.esmo.org/covid-19-and-cancer. Accessed 20 Dec 2020

AIOM (Associazione Italiana di Oncologia Medica). Assicurare il proseguimento delle terapie salva-vita per tutti i pazienti oncologici e onco-ematologici. Available from: https://www.aiom.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/20200407_appello_AIOM-AIRO-SIE.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2020

AIOM (Associazione Italiana di Oncologia Medica). Rischio infettivo da coronavirus covid 19: indicazioni per l’oncologia. Available from: https://www.aiom.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/20200313_COVID19_indicazioni_AIOM-CIPOMO-COMU.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2020

Dalu D, Rota S, Cona MS, Brambilla AM, Ferrario S, Gambaro A, Meroni L, Merli S, Farina G, La Verde N (2021) A proposal of a “ready to use” COVID-19 control strategy in an Oncology ward: utopia or reality? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 157:103168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.103168

Ng KYY, Zhou S, Tan SH, Ishak NDB, Goh ZZS, Chua ZY, Chia JMX, Chew EL, Shwe T, Mok JKY, Leong SS, Lo JSY, Ang ZLT, Leow JL, Lam CWJ, Kwek JW, Dent R, Tuan J, Lim ST, Hwang WYK, Griva K, Ngeow J (2020) Understanding the psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with cancer, their caregivers, and health care workers in Singapore. JCO Glob Oncol 6:1494–1509. https://doi.org/10.1200/GO.20.00374

Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, Wang W, Li J, Xu K, Li C, Ai Q, Lu W, Liang H, Li S, He J (2020) Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol 21(3):335–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6

Zhang L, Zhu F, Xie L et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of COVID-19-infected cancer patients: a retrospective case study in three hospitals within Wuhan, China. Ann Oncol 31(7):894–901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.296

Garassino MC, Whisenant JG, Huang LC et al (2020) COVID-19 in patients with thoracic malignancies (TERAVOLT): first results of an international, registry-based, cohort study. Lancet Oncol 21(7):914–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30314-4

de Zwart O, Veldhuijzen IK, Elam G, Aro AR, Abraham T, Bishop GD, Voeten HA, Richardus JH, Brug J (2009) Perceived threat, risk perception, and efficacy beliefs related to SARS and other (emerging) infectious diseases: results of an international survey. Int J Behav Med 16(1):30–40

Ding Y, Du X, Li Q, Zhang M, Zhang Q et al (2020) Risk perception of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and its related factors among college students in China during quarantine. PLoS One 15(8):e0237626

Erdem D, Karaman I (2020) Awareness and perceptions related to COVID-19 among cancer patients: a survey in oncology department. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 29(6):e13309. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13309

Palmer Kelly E, Meara A, Hyer M, Payne N, Pawlik TM (2020) Characterizing perceptions around the patient-oncologist relationship: a qualitative focus group analysis. J Cancer Educ 35(3):447–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-019-1481-6

Cortiula F, Pettke A, Bartoletti M, Puglisi F, Helleday T (2020) Managing COVID-19 in the oncology clinic and avoiding the distraction effect. Ann Oncol 31(5):553–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.286

Sirintrapun SJ, Lopez AM (2018) Telemedicine in Cancer Care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 23(38):540–545

Al-Shamsi HO, Alhazzani W, Alhuraiji A, Coomes EA, Chemaly RF, Almuhanna M, Wolff RA, Ibrahim NK, Chua MLK, Hotte SJ, Meyers BM, Elfiki T, Curigliano G, Eng C, Grothey A, Xie C (2020) A practical approach to the management of cancer patients during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: An International Collaborative Group. Oncologist 25(6):e936–e945

Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa PA, Nov O (2020) COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: Evidence from the field. J Am Med Inform Assoc 27(7):1132–1135

Ohannessian R, Duong TA, Odone A (2020) Global telemedicine implementation and integration within health systems to fight the COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action. JMIR Public Health Surveill 6(2):e18810

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Maria Silvia Cona: conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing

Eliana Rulli: data curation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing

Davide Dalu: writing—review and editing

Francesca Galli: data curation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing

Selene Rota: data curation; Sabrina Ferrario: data curation

Nicoletta Tosca: data curation

Anna Gambaro: data curation

Virginio Filipazzi: data curation

Sheila Piva: writing—review and editing

Nicla La Verde: conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, supervision

All authors contributed to manuscript revision and have read and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was gained from the internal Ethical Committee of the Luigi Sacco Hospital in Milan (Prot. nr: 34675/2020). Participants gave informed consent before filling the questionnaires. The information sheet included details on data anonymity and procedures for stopping participation.

Consent to participate

All participants signed informed consent before filling the questionnaires.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Dr. N. La Verde reports: grants from EISAI, speaker bureau, travel expences for conference from ROCHE , GENTILI, advisory role from NOVARTIS and CELGENE, advisor role, travel expences for conference from PFIZER, advisory board from MSD. Dr D. Dalu reports: speaker bureau, travel expences for conference from ROCHE, GENTILI. The other authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cona, M.S., Rulli, E., Dalu, D. et al. The emotional impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on cancer outpatients and their caregivers: results of a survey conducted in the midst of the Italian pandemic. Support Care Cancer 30, 1115–1125 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06489-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06489-y