Abstract

Symptoms of anxiety and depression often coexist, and evidence suggests that this has a genetic basis, among other possible causes. However, the current classification of comorbid generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) and depression (anxious depression) in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition; DSM-5) does not fully reflect the high prevalence of anxiety symptoms in people with depression and the International Classification of Diseases (10th and 11th revisions) has tended to identify anxious depression with minor disorders seen in primary care. As a result, few dedicated therapeutic trials have been conducted in patients with anxious depression, and specific treatment guidelines and recommendations are lacking. Fortunately, there is considerable therapeutic overlap between anxiety and depression, such that many agents with antidepressant efficacy are also effective for symptoms of GAD. The initial treatment of a patient with depression and symptoms of anxiety should be with an agent that is approved for both major depressive disorder and GAD, such as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. There is an obvious need for greater recognition of anxious depression in order to boost the volume of high-quality clinical data, which should translate over time into better, more specific treatment recommendations and improved outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Why carry out this review? |

Comorbid generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) and major depressive disorder is not yet universally recognised as a distinct disorder (i.e. as anxious depression), consequently therapeutic research and recommendations for this specific condition are lacking. |

What was learned from the review? |

Many antidepressant agents are also effective for symptoms of GAD, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). |

Likewise, drug classes used to treat GAD are also effective in the treatment of depression with anxious symptoms (e.g. SSRIs, serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants and agomelatine). |

Greater recognition of anxious depression and further clinical research in this specific patient population are required. |

Introduction

Among psychiatric disorders, generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) are the leading contributors to global disability and, indeed, both are among the top ten causes of disability-adjusted life-years worldwide [1].

Symptoms of anxiety and depression often coexist [2, 3]. Moreover, the presence of both GAD and MDD is strongly associated with a poor prognosis, an increase in severe symptoms, poorer quality of life, greater MDD recurrence, and a higher suicide risk than either disorder alone [4,5,6].

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

What is Anxious Depression?

Despite an increasing body of evidence describing the relationship between anxiety and depression [5,6,7], comorbid anxiety and depression does not have adequate recognition as a distinct clinical entity in the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Thus, a diagnosis of MDD does not require the presence of any symptoms of anxiety. DSM-5 includes anxious depression only as one among many subtypes of a major depressive episode, described by the specifier of anxious distress [8]. The two most recent versions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10 and ICD-11) include a rather different concept of ‘mixed anxiety and depressive disorder’. In ICD-10, it is defined as a condition (F41.2) where depression and anxiety are both present but neither to an extent that would justify a diagnosis of MDD or GAD separately. It was designed to capture minor disorders seen in primary care. One of the key differences between the criteria for a full syndrome of anxiety or depression is the time element. GAD requires 6 months of symptoms, MDD just 2 weeks. ICD-11 has introduced a clearer set of criteria, namely the presence of symptoms of both anxiety and depression on more days than not over at least 2 weeks [9, 10]. In primary care, anxious depression is much the commonest presentation amongst those seeking treatment. Despite its inclusion in ICD-10, a lack of randomised controlled trials means that guidelines cannot, at the present time, recommend evidence-based treatment options for patients with comorbid anxiety and depression [11].

Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression

The relative contributions of genetic and environmental factors to the development of anxiety and depression have been studied in pairs of monozygotic and dizygotic twins [7]. In these studies, MDD was found to be strongly genetic in origin, with very little contribution from the shared environment of the twin pairs; in contrast, GAD was more weakly associated with genetic factors, but more strongly correlated with the shared environment. The contribution of the non-shared (unique) environment was significant for both disorders, with ‘loss’ events promoting the development of MDD, and ‘threat’ events promoting the development of GAD.

In a recent study of the general UK population (N > 150,000), GAD and depression were found to have a strong genetic overlap but were partially distinct from fear-related disorders, such as phobias [2]. Phenotypically, GAD was strongly correlated with both depression and fear-related disorders, but there was a much weaker correlation between fear and depression. These findings imply a shared biology between GAD and depression, and suggest a close clinical relationship that is likely to have implications for treatment.

Treatment Options for Patients with Anxious Depression

Treatments for anxiety and depression include psychological interventions, pharmacological interventions, or a combination of both (Table 1) [12,13,14,15,16]. Psychological treatments, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, interpersonal therapy, behavioural activation, and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, are indicated in the management of MDD [14, 16]. However, although they are well tolerated [12], they may not be available or affordable, and tend to be time-consuming.

In a recent large network meta-analysis of 21 pharmacotherapies for depression, all of the agents studied were more efficacious than placebo (in terms of response rate), with odds ratios for response ranging from 1.37 with reboxetine to 2.13 with amitriptyline (Fig. 1) [13]. In terms of acceptability, defined as the inverse of all-cause treatment discontinuation, only agomelatine and fluoxetine were superior to placebo. Many drug classes used in the treatment of GAD are also effective in the treatment of depression with anxious symptoms (e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants and agomelatine), with the exception of benzodiazepines and anticonvulsants, such as pregabalin. However, benzodiazepines do have a place as adjuncts in the treatment of MDD associated with insomnia or other symptoms of anxiety, and there is evidence to support the addition of a benzodiazepine to antidepressant treatment in the short term (1–4 weeks) [17].

Forest plots from network meta-analyses showing a efficacy and b acceptability of various antidepressants when compared with placebo in patients with major depressive disorder [odds ratios (ORs) and 95% credible intervals (CrI)]; and c efficacy of pharmacological and psychological interventions for generalised anxiety disorder [standardised mean differences and 95% confidence intervals (CI)]. Panels a and b reprinted from The Lancet, Vol. 391, Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis, pages 1357–66, Copyright (2018) [13], under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Panel c was reprinted from the Journal of Psychiatric Research, Vol 118, Chen TR, Huang HC, Hsu JH, Ouyang WC, Lin KC. Pharmacological and psychological interventions for generalized anxiety disorder in adults: a network meta-analysis, pages 73–83, Copyright (2019) [12], with permission from Elsevier. ACV anticonvulsant, Analysis analysis-based psychotherapy, AppliedRelax applied relaxation, BZD benzodiazepine, CrI credible interval, GCBT group cognitive behavioural therapy, ICBT individual cognitive behavioural therapy, Mindful mindfulness-based psychotherapy, MRA melatonin receptor agonist, NaSSA noradrenaline and specific serotonin antidepressant, NDRI noradrenaline-dopamine reuptake inhibitor, OR odds ratio, Other other psychological intervention, PsyPlacebo psychological placebo, SGA second-generation antipsychotic, SHCG self-help control group, SHWS self-help with support, SModulator serotonin modulator, SNRI serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, SSRI selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

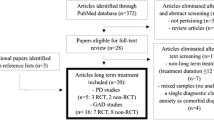

As there are only a few randomised controlled therapeutic trials specifically conducted in patients with comorbid anxiety and depression, evidence-based recommendations are lacking [11]. In guidelines issued by the British Association for Psychopharmacology in 2015 [14], antidepressants were described as being generally effective for the treatment of comorbid anxiety, but few specific recommendations were made. The authors noted that, although SSRIs were the most studied agents in this setting, there was little evidence that one class was superior to another [14]. The 2016 Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments clinical guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of MDD are more detailed, but still contain few specific recommendations on the treatment of anxious depression, including the use of an antidepressant that has proven efficacy in GAD [15].

Encouraging recent data do, however, come from the PREDICT study [18] and the PANDA trial [19]. PREDICT is a recent analysis of anxiety and depression symptoms in 900 patients who received treatment for MDD (mainly SSRIs) in primary care [18]. Scores on the General Anxiety Disorder-7 and Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-16 scales showed a high degree of correlation at both baseline and after 8 weeks’ treatment, indicating that treatment that was effective for depression was also effective for anxiety symptoms [18]. In the pragmatic PANDA trial [19], sertraline was found to improve anxiety symptoms compared with placebo in patients with depression (n = 655).

Some agents with a novel mechanism of action may be useful in patients with anxious depression. The serotonin modulator vortioxetine is a serotonin 5-HT3 antagonist and 5-HT1A agonist. It is approved for MDD and has been investigated in patients with GAD, but did not show sufficient therapeutic efficacy in this indication required to pursue regulatory approval in the USA [20]. However, there is evidence from a meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials that it is effective in treating anxiety symptoms in patients with MDD who also have high levels of anxiety [21]. Buproprion has broad pharmacological action—being a noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitor—and is approved for the treatment of patients with MDD, but is used off-label in GAD [20]. A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomised studies reported that bupropion improved symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with anxious depression, albeit to a slightly smaller degree than SSRIs [22].

At present, the most appropriate recommendation that can be made for patients who have symptoms of both anxiety and depression is to use an evidence-based antidepressant that has efficacy in the treatment of anxiety symptoms. Moving forward, there is a need for greater awareness and recognition of anxious depression by both the clinical and research communities; physicians should routinely screen for symptoms of anxiety in their patients with depression, and modify their approach to treatment and monitoring accordingly. In the research setting, dedicated trials in patients with comorbid anxiety and depression are needed, as is the more widespread inclusion of anxiety symptoms as an endpoint in studies of MDD.

Conclusion

Depression and GAD are closely related and often coexist, suggesting a common biological basis for both disorders. Under-recognition of anxious depression as a clinical entity has hindered the availability of clinical data, such that there are few specific treatment guidelines or recommendations for people with symptoms of both disorders. Antidepressants with proven efficacy against anxiety symptoms should be the first choice of treatment, with the short-term addition of a benzodiazepine being considered when additional control of specific anxiety symptoms is needed.

References

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–22.

Morneau-Vaillancourt G, Coleman JRI, Purves KL, et al. The genetic and environmental hierarchical structure of anxiety and depression in the UK Biobank. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(6):512–20.

Saha S, Lim CCW, Cannon DL, et al. Co-morbidity between mood and anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2020;38(3):286–306.

Zhou Y, Cao Z, Yang M, et al. Comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and its association with quality of life in patients with major depressive disorder. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):40511.

McIntyre RS, Woldeyohannes HO, Soczynska JK, et al. The prevalence and clinical characteristics associated with diagnostic and statistical manual version-5-defined anxious distress specifier in adults with major depressive disorder: results from the international mood disorders collaborative project. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2016;7(3):153–9.

Gaspersz R, Nawijn L, Lamers F, Penninx B. Patients with anxious depression: overview of prevalence, pathophysiology and impact on course and treatment outcome. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31(1):17–25.

Kendler KS. Major depression and generalised anxiety disorder. Same genes, (partly) different environments--revisited. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168(Suppl 30):68–75.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric; 2013.

World Health Organization. ICD-10 Version: 2019 https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en. Accessed 26 January 2021.

World Health Organization. ICD-11 for mortality and morbidity statistics (version: 09/2020). https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en. Accessed 26 January 2021.

Möller HJ, Bandelow B, Volz HP, Barnikol UB, Seifritz E, Kasper S. The relevance of “mixed anxiety and depression” as a diagnostic category in clinical practice. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;266(8):725–36.

Chen TR, Huang HC, Hsu JH, Ouyang WC, Lin KC. Pharmacological and psychological interventions for generalized anxiety disorder in adults: a network meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;118:73–83.

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1357–66.

Cleare A, Pariante CM, Young AH, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2008 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(5):459–525.

Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 3. Pharmacological treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):540–60.

Parikh SV, Quilty LC, Ravitz P, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 2. Psychological treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):524–39.

Ogawa Y, Takeshima N, Hayasaka Y, et al. Antidepressants plus benzodiazepines for adults with major depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6:CD001026.

Browning M, Bilderbeck AC, Dias R, et al. The clinical effectiveness of using a predictive algorithm to guide antidepressant treatment in primary care (PReDicT): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-021-00981-z.

Lewis G, Duffy L, Ades A, et al. The clinical effectiveness of sertraline in primary care and the role of depression severity and duration (PANDA): a pragmatic, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(11):903–14.

Garakani A, Murrough JW, Freire RC, et al. Pharmacotherapy of anxiety disorders: current and emerging treatment options. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:595584.

Baldwin DS, Florea I, Jacobsen PL, Zhong W, Nomikos GG. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of vortioxetine in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and high levels of anxiety symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2016;206:140–50.

Papakostas GI, Stahl SM, Krishen A, et al. Efficacy of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of major depressive disorder with high levels of anxiety (anxious depression): a pooled analysis of 10 studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(8):1287–92.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This supplement has been sponsored by Servier, France. This funding includes payment of the Journal’s Rapid Service Fee and Open Access Fee.

Medical Writing Assistance

We would like to thank Alma Orts-Sebastian, PhD, and Richard Crampton of Springer Healthcare Communications, who wrote the first and subsequent drafts of this article. Funding for this medical writing assistance was provided by Servier.

Authorship

The named author meets the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and has given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Prof Goodwin prepared the lecture on which this article is based, read, revised and edited all drafts, and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Prior Presentation

This review and the accompanying articles in this supplement are based on presentations made by the authors at a Servier-funded virtual symposium titled “GAD and Depression: Contemporary Treatment Approaches” as part of the Industry Science Exchange sessions that took place at the European College of Neuropsycopharmacology 33rd Congress in September 2020.

Disclosures

Guy M. Goodwin is a NIHR Emeritus Senior Investigator and Medical Director at P1vital products, holds shares in P1vital and P1vital products, has served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker in the last 3 years for Beckley Psytech, Clerkenwell Health, Compass pathways, Evapharma, Janssen, Lundbeck, Medscape, Novartis, Ocean Neuroscience, P1Vital, Sage, Servier, and has received an honorarium from Servier for the presentation on which this publication is based. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Goodwin, G.M. Revisiting Treatment Options for Depressed Patients with Generalised Anxiety Disorder. Adv Ther 38 (Suppl 2), 61–68 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01861-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01861-0