Abstract

Introduction

Pre-existing conditions relevant for adverse events (AE) and the potential for drug–drug interactions (DDIs) may limit safe pharmacotherapeutic augmentation options for patients with major depressive disorder (MDD). This concern may be heightened among patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD), who often have comorbid medical disorders.

Methods

Adults with MDD and ≥ 1 antidepressant claim within the first observed major depressive episode were identified in the MarketScan® Databases. Those initiating a new regimen after two regimens at adequate dose and duration were considered to have TRD. The index date was defined at TRD onset or on a random antidepressant claim among patients with non-TRD MDD. Pre-existing conditions 12 months pre-index and potential DDIs 3 months pre/post-index associated with specific non-antidepressant augmentation therapies, including atypical antipsychotics (APs), buspirone, psychostimulants, anticonvulsants, thyroid hormone, and lithium were compared between 1:1 matched TRD and non-TRD MDD cohorts.

Results

Overall, 3414 patients with TRD and non-TRD MDD (mean age 39.7 years, 69% female) were matched. Relative to non-TRD MDD, patients with TRD had 33% higher likelihood of ≥ 1 pre-existing condition relevant for AEs listed in product labels of non-antidepressant augmentation therapies (p < 0.001). Patients with TRD vs. non-TRD MDD had 12.9 and 6.4 times higher likelihood of ≥ 2 and ≥ 3 DDIs, respectively, based on their medication regimen (all p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Pre-existing conditions relevant for listed AEs and potential DDIs limit safe augmentation options in MDD, particularly among patients with TRD. Payer prior authorization policies requiring several augmentation therapy trials to access novel treatments may complicate clinical management of this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Among patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD), 82% had at least one pre-existing condition relevant for an adverse event (AE) listed in the product labels of non-antidepressant augmentation medications; 98% had a dispensed medication with potential for at least two moderate or severe drug–drug interactions (DDIs). |

In patients with TRD, the likelihood of at least one pre-existing condition relevant for a listed AE related to non-antidepressant augmentation medications was 33% higher, and the likelihood of at least two dispensed medications with potential for DDIs was 12.9 times greater compared to patients with non-TRD major depressive disorder (MDD). |

Pre-existing conditions relevant for listed AEs of non-antidepressant augmentation medications, as well as dispensed medications with potential for DDIs, limit the number of available safe augmentation options for MDD, particularly among patients with TRD. |

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a prevalent chronic condition associated with persistently depressed mood, loss of interest, and reduced social and occupational functioning [1]. An estimated 19.4 million adults experienced at least one major depressive episode (MDE) in 2019 in the USA, representing 7.8% of the adult US population [2].

Antidepressants are the standard of pharmacological care for patients with MDD, with approximately 50% of all patients experiencing an MDE reporting receiving pharmacological therapy [3]. Among patients with MDD who receive pharmacological therapy, between 10% and 33% fail to respond to at least two different antidepressant treatment courses of adequate dose and duration in the current MDE [4,5,6,7]. Failure to respond to at least two antidepressant treatment courses of adequate dose and duration is the most common definition of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in the medical literature, and cited by both the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medical Association (EMA); however, clinical guidelines have yet to endorse an operational definition of TRD [8, 9]. As such, on the basis of this definition, patients discontinuing treatment prematurely (prior to what is considered adequate duration) as a result of tolerability would not be considered to have experienced treatment failure for that medication. Reasons for treatment failure can vary and, in addition to the lack of efficacy, may include patient non-compliance, intolerable adverse events (AEs), or negative effects on treatment response caused by comorbid conditions and associated concomitant medications [10, 11]. Moreover, given the heterogeneity of MDD, patients may not be receiving treatments that are matched to their individual clinical profiles [12]. Irrespective of the definition employed, patients with TRD experience significantly higher healthcare resource utilization, direct and indirect healthcare costs, lower work productivity, and decreased health-related quality of life compared to patients with non-TRD MDD [13,14,15].

Patients with TRD typically require a combination of different pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies. The former may include dose optimizations, antidepressant treatment switches, combining multiple antidepressants, and augmentation with non-antidepressant augmentation medications [16, 17]. Clinical management of TRD can be challenging. Specifically, patients with TRD often present with comorbid physical (e.g., diabetes, hypertension) [18] and psychiatric (e.g., anxiety, substance use disorder) [19] conditions, which may complicate clinicians’ efforts to manage TRD and limit the array of safe pharmacological options for individual patients [20, 21]. As a result of comorbid conditions, patients with TRD may be using multiple medications concomitantly, increasing the risk of AEs and potential drug–drug interactions (DDIs). Payer pre-authorization requirements or formulary restrictions may limit access to safe treatment options and this may negatively impact clinical outcomes [22].

A prior retrospective claims-based study quantified the prevalence of relevant pre-existing conditions (movement disorders, metabolic disorders, cardiac abnormalities, comorbid psychiatric disorders) and severity of potential DDIs among patients with MDD who were treated with atypical antipsychotics (APs) [21]. Among patients with MDD initiated on an atypical AP, at least 30% had a relevant pre-existing condition or a potential DDI, which may have made the use of certain atypical AP medications inappropriate in these patients [21]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study to date has evaluated pre-existing conditions relevant for listed AEs and potential DDIs associated with augmentation therapies, including APs, among patients with TRD.

The purpose of this study was to bridge this gap in knowledge and compare the prevalence of pre-existing conditions related to AEs listed in the product labels, as well as dispensed medications with potential for DDIs related to commonly used atypical APs and other non-antidepressant augmentation medications among adult commercially and Medicaid insured US patients with TRD vs. those with non-TRD MDD.

Methods

Data Source

The IBM® MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases (October 1, 2015–March 4, 2019) as well as Multi-State Medicaid Database (October 1, 2015–December 31, 2018) were used. The Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases contain information on privately insured individuals covering all US census regions, with a concentration in the South and North Central (Midwest) regions. The Multi-State Medicaid database contains information on beneficiaries from 11 states, but specific states included are unknown and cannot be differentiated. The information in the databases includes claimant demographics, insurance eligibility, and medical and prescription drug claims. Data that support the findings of this study were used under license from IBM® Watson Health™. All data are de-identified and fully comply with the patient confidentiality requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Per Title 45 of Code of Federal Regulations, Part 46.101(b)(4) [23], the analysis of our study is exempt from institutional review for the following reasons: (a) it is a retrospective analysis of existing data with no patient intervention or interaction, and (b) no patient identifiable information is included in the claims dataset.

Study Design

A retrospective matched cohort design was used. Adults with TRD (the TRD cohort) were matched and compared to adults with MDD but without TRD (the non-TRD MDD cohort). The study period spanned from October 1, 2015 to March 4, 2019.

For patients in the TRD cohort, the index date was the date of TRD onset identified using a claims-based algorithm (see Sect. “Cohort Definitions”). For patients in the non-TRD MDD cohort, the index date was randomly selected among all dates with an antidepressant claim. Patient characteristics and the prevalence of pre-existing conditions related to AEs listed in the product labels were evaluated in the 12-month period before the index date, which was defined as the baseline period. The prevalence of potential DDIs was based on medications dispensed in the 90 days before and after the index date; prescriptions filled outside of this window but with days of supply that overlap the index date were also considered for this analysis.

Cohort Definitions

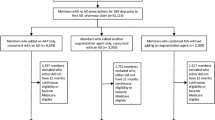

This section summarizes the definitions of study cohorts, while specific inclusion and exclusion criteria and patient attrition are presented in Fig. 1. The TRD and non-TRD MDD cohorts were identified within the first observed and treated MDE. The first observed MDE was defined as a period which started on the date of the first observed MDD diagnosis (no MDD diagnoses or antidepressant claims were permitted in ≥ 6 months before the MDE start). The end of the MDE (if observed in the data) was defined as the later of the two dates: either the last MDD diagnosis or the end of antidepressant medication supply before ≥ 6 months without MDD diagnoses or antidepressant claims.

Study participant flowchart. ICD-10-CM International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification, MDD major depressive disorder, MDE major depressive episode, TRD treatment resistant depression.1Diagnosis codes used for the identification of MDD are ICD-10-CM F32.X [excluding F32.8] and F33.X [excluding F33.8]. 2An MDE refers to a period with diagnoses and therapies received for MDD. The episode start date is the date of the first observed MDD diagnosis preceded by a period of ≥ 6 months (180 days) without MDD diagnoses or antidepressants (clean period). The episode end date is the later of the two followed by a ≥ 6 months clean period: date of the last MDD diagnosis or last day with antidepressant supply (last fill date + days’ supply). 3Adequate dose was defined on the basis of the recommended daily dose for ≥ 6 weeks as indicated in the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire, as included in Supplementary Table 1. Adequate duration was defined as ≥ 6 weeks of continuous therapy with no gaps > 14 days. 4TRD onset was defined as the initiation of a new antidepressant treatment course after absence of a response to two antidepressant treatment courses of adequate dose and duration. 5The index date for patients with non-TRD MDD was randomly selected among all dates with an antidepressant medication claim. 6Patients were excluded if they had ≥ 1 claim with a diagnosis for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ICD-10-CM: F90.x), bipolar disorder (ICD-10-CM: F31.xx), cyclothymic disorder (ICD-10-CM: F34.0x), dementia (ICD-10-CM: F01.xx, F02.xx, F03.xx, G30.xx, G31.0x, G31.1x), epilepsy (ICD-10-CM: G40.xxx), or psychosis, schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorder, and other non-mood psychotic disorders (ICD-10-CM: F06.0x, F06.2x, F20.xx, F21.xx, F22.xx, F23.xx, F24.xx, F25.xx, F28.xx, F29.xx)

The definition of TRD onset relied on several recent claims-based studies [14, 15, 18, 19, 24, 25]. Specifically, TRD onset was defined as the initiation of a new antidepressant treatment course (i.e., either a claim for a new antidepressant of adequate dose or a claim for a new non-antidepressant augmentation medication overlapping with a claim for an antidepressant of adequate dose) after the absence of a response to two antidepressant treatment courses of adequate dose and duration. The absence of response was defined as a change of a treatment course including a switch of an antidepressant or an initiation of augmentation therapy (i.e., an addition of a new antidepressant, or an addition of a new non-antidepressant augmentation medication). Adequate duration was defined as at least 6 weeks of continuous therapy with no gaps longer than 14 days. Adequate dose was defined as a minimum starting dose recommended by the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ) for non-geriatric and geriatric patients (Supplementary Table 1). Selection of non-antidepressant augmentation medications was based on the American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines for the treatment of patients with MDD [26], the FDA-approved product labels denoting the indication, and other options commonly used for MDD (Supplementary Table 2).

Patients with ≥ 1 claim for an antidepressant at adequate dose and duration during the first observed MDE and without observed evidence of TRD onset were considered to have non-TRD MDD.

Patients in both cohorts were required to have ≥ 12 months of continuous insurance eligibility prior to the index date, ≥ 3 months of continuous insurance eligibility after the index date, and be ≥ 18 years old at the index date. Patients were excluded from the study if they had diagnoses for specific exclusionary psychiatric conditions (i.e., attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, cyclothymic disorder, dementia, epilepsy, or psychosis/schizophrenia) during the study period.

Study Outcomes

Study outcomes included pre-existing conditions relevant for AEs listed in the product labels and potential DDIs with non-antidepressant augmentation medications. In the main analysis, outcomes in both cohorts were evaluated regardless of the receipt of medications analysed in two ways: (1) based on all medications including FDA-approved and other common options and (2) by medication class. For each class, the most commonly used non-antidepressant augmentation medications at TRD onset were considered (Table 2).

A subgroup analysis evaluated outcomes among patients with TRD newly initiated on non-antidepressant augmentation medications at TRD onset. New initiation was defined as the absence of a claim for the medication in the 12-month baseline period.

Pre-existing conditions relevant for AEs listed in the product labels of non-antidepressant augmentation medications were identified on the basis of the history of a given condition evaluated in the 12-month baseline period. The “Warnings and Precautions” and “Adverse Reactions” sections of the FDA Prescribing Information for each specific non-antidepressant augmentation medication of interest were used to identify qualifying relevant pre-existing conditions, with the rationale being that patients already having these conditions would likely be at a higher risk of developing AEs if treated with that medication [21, 27].

Potential DDIs with non-antidepressant augmentation medications, including both moderate and severe, were identified on the basis of pharmacy claims for other medications dispensed in the 90 days before and after the index date using the IBM Micromedex® Drug Interaction Checking tool.

Statistical Analysis

Patients with TRD were matched 1:1 to patients with non-TRD MDD on the basis of exact matching factors (i.e., year of the index date and insurance plan type) and propensity scores computed on the basis of age, sex, and time between the first antidepressant claim and the index date. The balance of baseline characteristics between cohorts after matching was assessed with standardized differences (< 10% indicated balanced) [28].

The likelihoods of presence of a relevant pre-existing condition for listed AEs and potential DDIs were compared between matched cohorts using univariate logistic regressions that accounted for the correlation between matched pairs. Results were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p values.

Results

Among 274,910 patients with an MDD diagnosis and an antidepressant claim at adequate dose and duration during the first observed MDE, 9740 (4%) were identified as having TRD (Fig. 1). Among patients with TRD, 3414 (35%) met all study selection criteria. In the non-TRD MDD cohort, a total of 110,354 patients were identified and matched to patients in the TRD cohort. Following matching, each of the cohorts included 3414 patients.

Baseline Characteristics

After matching, the TRD and non-TRD MDD cohorts were well balanced in terms of demographic characteristics (Table 1). In both cohorts, the mean age was 39.7 years, 69% of patients were female, 4% had access to Medicare Supplemental, and 27% were covered by Medicaid. Race was available only in those with Medicaid coverage, and the majority of patients with data regarding race available were white in both cohorts. During the baseline period, patients with TRD compared to patients with non-TRD MDD received, on average, one additional unique antidepressant (a mean of 2.5 vs. 1.4). In the TRD cohort, 48% received a non-antidepressant augmentation agent during the baseline period, compared to 19% in the non-TRD MDD cohort.

In the TRD cohort, 1824 patients (53%) initiated non-antidepressant augmentation medications at TRD onset (Table 2). The most common medications received were adjunctive atypical APs (35%), buspirone (31%), and thyroid hormones (27%); lithium was the least commonly used medication (1%). Among patients who initiated non-antidepressant augmentation medications at TRD onset, 986 (54%) had not received the medication being initiated during the baseline period (i.e., were new initiators). Atypical APs was the most common class of newly initiated non-antidepressant augmentation medications (36%).

Pre-Existing Conditions

Among patients with TRD, the prevalence of ≥ 1 pre-existing condition relevant for listed AEs (based upon the “Warnings and Precautions” and “Adverse Reactions” sections in the prescribing information) related to any non-antidepressant augmentation medication was 82%. The likelihood of presence of ≥ 1 pre-existing condition relevant for a listed AE related to any non-antidepressant augmentation medication was 33% higher in patients with TRD relative to patients with non-TRD MDD (p < 0.001).

The proportion of patients with TRD with ≥ 1 pre-existing condition relevant for listed AEs related to the most commonly used medications in each specific non-antidepressant augmentation class (Table 2) ranged between 28% (anticonvulsants) and 65% (atypical APs; Fig. 2). Patients with TRD compared to patients with non-TRD MDD had 46%, 45%, and 40% higher likelihood of having ≥ 1 pre-existing condition relevant for a listed AE specific to atypical APs, amphetamine-related psychostimulants, and thyroid hormones, respectively (all p < 0.001; Fig. 2).

Likelihood of having any pre-existing condition relevant for AEs associated with specific non-antidepressant augmentation medications in patients with TRD vs. non-TRD MDD (N = 3414 per cohort)1. AE adverse event, CI confidence interval, FDA US Food and Drug Administration, MDD major depressive disorder, OR odds ratio, TRD treatment-resistant depression.*Significant at the 5% level. 1Pre-existing conditions were identified based on the “Warnings and Precautions” and “Adverse Reactions” sections of the FDA Prescribing Information for each medication included in each class of non-antidepressant augmentation medications. 2ORs, 95% CIs, and p values were calculated with univariate generalized estimating equations using logistic regression to account for the matched pairs

The most prevalent pre-existing conditions relevant for listed AEs among patients with TRD were respiratory conditions (51%; relevant to use of lithium), cardiovascular conditions (29%; relevant to use of atypical APs, non-benzodiazepine GABA-receptor modulators, modafinil- and amphetamine-related psychostimulants, thyroid hormones, and lithium), and hypertension (27%; relevant to use of non-benzodiazepine GABA-receptor modulators, modafinil- and amphetamine-related psychostimulants, and thyroid hormones). Common pre-existing conditions relevant for listed AEs specific to atypical APs, which were significantly more likely to be observed among patients with TRD relative to patients with non-TRD MDD, were cardiovascular (13% higher likelihood in the TRD cohort), obesity/weight gain (17% higher likelihood), and hyperlipidemia/dyslipidemia (15% higher likelihood; Fig. 3). These conditions were also similarly associated with the use of other classes of non-antidepressant augmentation medications.

Likelihood of having specific pre-existing condition relevant for AEs associated with atypical APs in patients with TRD vs. non-TRD MDD (N = 3414 per cohort)1. AE adverse event, AP antipsychotic, CI confidence interval, FDA US Food and Drug Administration, MDD major depressive disorder, OR odds ratio, TRD treatment-resistant depression.*Significant at the 5% level. 1Pre-existing conditions were identified based on the “Warnings and Precautions” and “Adverse Reactions” sections of the FDA Prescribing Information for each medication included in each class of non-antidepressant augmentation medications. 2ORs, 95% CIs, and p values were calculated with univariate generalized estimating equations using logistic regression to account for the matched pairs

In the sensitivity analysis (i.e., in the subgroup of new initiators of non-antidepressant augmentation medications at TRD onset), 66% of patients who initiated an atypical AP had ≥ 1 pre-existing condition for a listed AE relevant to use of an atypical AP (Supplementary Fig. 1). The likelihood of presence of ≥ 1 pre-existing condition for listed AEs relevant to use of an atypical AP was 66% higher in patients with TRD initiating atypical APs compared to patients with non-TRD MDD (p < 0.001). With respect to specific conditions relevant to use of atypical APs, the likelihoods for cardiovascular conditions, obesity/weight gain, and hyperlipidemia/dyslipidemia were similar in patients with TRD initiating atypical APs and patients with non-TRD MDD; patients with TRD initiating atypical APs had 138% higher likelihood of insomnia and 50% higher likelihood of hypothyroidism relative to patients with non-TRD MDD (all p < 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 2).

Potential DDIs

All patients with TRD and non-TRD MDD had ≥ 1 potential moderate or severe DDI related to any non-antidepressant augmentation medication (Fig. 4). Moreover, virtually all patients with TRD (98% and 91%) had ≥ 2 and ≥ 3 potential moderate or severe DDIs related to any non-antidepressant augmentation medication, respectively. The likelihood of ≥ 2 and ≥ 3 potential DDIs was 12.9 and 6.4 times higher among patients with TRD relative to patients with non-TRD MDD, respectively (all p < 0.001).

Likelihood of potential severe or moderate DDIs in patients with TRD vs. non-TRD MDD (N = 3414 per cohort)1. CI confidence interval, DDI drug–drug interaction, MDD major depressive disorder, OR odds ratio, TRD treatment-resistant depression. *Significant at the 5% level. 1The number of dispensed medications with potential for DDIs for each class of non-antidepressant augmentation medications was identified during a 90-day window before and after index date or among prescriptions with days of supply that overlap the index date. 2ORs, 95% CIs, and p values were calculated with univariate generalized estimating equations using logistic regression to account for the matched pairs

The prevalence of ≥ 1 potential moderate or severe DDI specific to each class of medications (Table 2) among patients with TRD ranged from 59% for thyroid hormones to 100% for amphetamine-related psychostimulants and was 98% for atypical APs (Fig. 4). The likelihood of ≥ 1 potential DDI related to atypical APs and amphetamine-related psychostimulants was similar among patients with TRD and non-TRD MDD, but patients with TRD had higher likelihood of ≥ 1 potential DDI for all other classes of medications. The prevalence of ≥ 2 potential DDIs among patients with TRD ranged from 18% for anticonvulsants to 91% for amphetamine-related psychostimulants and was 85% for atypical APs. Patients with TRD compared to patients with non-TRD MDD had 4.5 and 3.4 times higher likelihood of ≥ 2 and ≥ 3 potential DDIs related to atypical APs (all p < 0.001), and, similarly, higher likelihood of ≥ 2 and ≥ 3 potential DDIs for all other classes of medications.

In the sensitivity analysis, 100%, 98%, and 81% of patients who newly initiated an atypical AP at TRD onset had ≥ 1, ≥ 2, and ≥ 3 potential DDIs relevant to use of atypical APs, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3). Patients with TRD newly initiating atypical APs had 36.2 and 9.8 times higher likelihood of ≥ 2 and ≥ 3 potential DDIs related to atypical APs compared to patients with non-TRD MDD (p < 0.001). A statistically significant higher likelihood of ≥ 2 and ≥ 3 potential DDIs was largely observed among patients with TRD initiating all other classes of medications, with the exception of modafinil-related psychostimulants (in this case, the likelihood of ≥ 3 potential DDIs was similar between cohorts).

Discussion

In this real-world observational study, the prevalence of pre-existing conditions relevant for AEs listed in the product labels of specific non-antidepressant augmentation therapies and potential DDIs were assessed between patients with TRD and non-TRD MDD. Our findings demonstrate that most patients with TRD had ≥ 1 pre-existing condition relevant for a listed AE and ≥ 3 potential moderate or severe DDIs associated with non-antidepressant augmentation therapy. The likelihoods of having relevant pre-existing conditions as well as the potential for multiple DDIs were significantly higher in patients with TRD compared to those with non-TRD MDD. Overall, these findings emphasize the challenges of pharmacological management of patients with TRD and the need for careful clinical decision-making to select therapies that minimize the risk of AEs and potential DDIs.

Atypical APs were the most commonly used class of non-antidepressant augmentation medications at the time of TRD onset while lithium was the least commonly used; this was consistent with recent claims-based analyses of patients with TRD [14, 29, 30]. A third of patients with TRD who used non-antidepressant augmentation medications at TRD onset were treated with an atypical AP (aripiprazole, quetiapine, or brexpiprazole). A previous claims-based study of patients with MDD and other psychiatric conditions initiated on atypical APs reported that the prevalence of ≥ 1 pre-existing condition relevant for a listed AE was 32% for aripiprazole and 77% for quetiapine [21]. In our study, we found that 65% of all patients with TRD regardless of the initiation of APs and 66% of those who initiated a new atypical AP at TRD onset had ≥ 1 relevant pre-existing condition potentially impacting them from safely using aripiprazole or quetiapine.

Physical comorbid conditions, including cardiovascular, metabolic, and respiratory disease, are prevalent among patients with TRD [18]. In this study, we found a significantly higher likelihood of cardiovascular disease, obesity/weight gain, and hyperlipidemia/dyslipidemia in patients with TRD vs. those with non-TRD MDD. These conditions may preclude the use of atypical APs because of an increased risk for clinically relevant AEs. The interplay of physical comorbidities and TRD is complex and has not been well elucidated. It is possible that these physical conditions impact the success of antidepressants and non-antidepressant augmentation medications among patients with MDD, resulting in a higher prevalence of comorbidities among patients with TRD, or alternatively individuals with comorbid conditions may experience poorer mental health outcomes.

The risk of potential moderate and severe DDIs due to being on multiple medications, which have an undesirable reaction with non-antidepressant augmentation medications, is high among patients with TRD. Almost all patients with TRD had ≥ 2 and ≥ 3 potential moderate or severe DDIs associated with any non-antidepressant augmentation therapy; moreover, 85% had ≥ 2 potential DDIs associated with an atypical AP, the most commonly used class of non-antidepressant augmentation medications. Careful assessment of potential DDIs is important in this population because of the concurrent treatment of other comorbidities, in addition to TRD.

The main analysis of this study focused on patients regardless of their actual initiation of non-antidepressant augmentation medications, but the sensitivity analysis assessed the outcomes in patients who newly initiated the medications at TRD onset. The prevalence of ≥ 1 pre-existing condition for a listed AE relevant for use of an atypical AP was similar, regardless of the initiation status, but the prevalence of cardiovascular conditions and hyperlipidemia was somewhat lower in new initiators of non-antidepressant augmentation medications relative to all patients with TRD. With respect to potential DDIs, their prevalence was higher in new initiators of non-antidepressant augmentation medications relative to all patients with TRD. Overall, it is recognized that the pharmacological management of patients with TRD with pre-existing conditions for which they are taking other medications is challenging for clinicians. In addition to these challenges, clinicians managing patients with TRD additionally face the difficulty of finding a treatment option that would help alleviate the symptoms of MDD, as few augmentation options are proven to be effective. While the scope of this study was to assess the prevalence of pre-existing conditions relevant for AEs listed in the product labels of non-antidepressant augmentation agents, future studies should consider evaluating the impact of antidepressant therapies on outcomes among patients with pre-existing conditions.

The current study found that 4% of patients with MDD treated with antidepressants met the criteria for TRD. Of note, the proportion of patients with MDD that appear to meet the definition of TRD in claims-based studies varies on the basis of several factors including the duration of follow-up, constraints imposed by patient exclusion criteria, the extent of non-antidepressant augmentation agents being considered, and the thresholds for definitions of adequate dose and duration for antidepressant treatment.

New therapeutic options are available to treat TRD and are generally covered by payers in the USA. However, payers may require pre-authorization, where patients must demonstrate failure to alternative augmentation therapy with non-antidepressant augmentation medications before they can receive access to these options. Requiring patients with TRD to fail adjunctive AP therapy prior to allowing treatment with newer therapeutic options restricts the clinician’s flexibility in this complex patient population, which has higher rates of comorbid medical conditions compared to patients with non-TRD MDD. Consequently, it may prolong the course of the patient’s illness, increase the risk of AEs and DDIs, and delay access to alternative treatments. While new therapeutic options similarly carry the risk of AEs, there is a clinical benefit to broadening the array of available options, rather than limiting choices on the basis of payer restrictions, to further aid in the creation of individualized treatment plans.

Limitations

The current study is subject to some limitations. First, the definition of TRD was based uniquely on pharmacy claims for antidepressant and non-antidepressant augmentation medications, and clinical information related to the response to these medications, as well as evaluation of tolerability or actual AEs, was not available. Second, although the most common definition of TRD was used [8], there remains no established or consistent definition in clinical practice guidelines routinely used in the care of patients. Third, as with all claims database studies, pharmacy claims do not guarantee that the medication dispensed was taken as prescribed. It is possible that patients may have been instructed to stop taking a given medication before starting non-antidepressant augmentation medications, thus leading to the overestimation of the prevalence of potential DDIs. The present study assessed the prevalence of pre-existing conditions relevant for AEs listed in the product labels, not the prevalence of actual AEs, and there is no assumption that actual AEs occurred. Furthermore, patients may have been managing symptoms by using other medications, and certain pharmacodynamic interactions may have mitigated the actual likelihood of some AEs or DDIs. Diagnoses that are reported in claims databases are for administrative purposes and may be inaccurately reported. Reasons for potential underreporting may include social stigma associated with MDD, patient concerns regarding loss of insurance coverage, and preferred reporting of comorbid conditions when present with concurrent MDD [31]. Although matching techniques were used to minimize potential confounding, comparisons may be subject to residual confounding due to unmeasured confounders, e.g., level of education or marital status. Finally, results of this study may not be generalizable to patients without health insurance, or to patients covered by healthcare plans other than commercial insurance or Medicaid.

Conclusions

Effective and safe treatment options for patients with TRD may be limited given the high prevalence of pre-existing comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions relevant for AEs listed in the product labels of non-antidepressant augmentation therapies. Furthermore, patients with TRD receive medications that may result in DDIs with non-antidepressant augmentation therapies. Pre-existing conditions and the potential for DDIs associated with commonly used non-antidepressant augmentation therapies, such as atypical APs, further complicate the clinical management of patients with TRD. Pre-authorization conditions for novel therapeutic options in depression may pose an additional barrier to patient care in TRD.

References

Lin J, Szukis H, Sheehan JJ. Economic burden of treatment-resistant depression among patients hospitalized for major depressive disorder in the United States. Psych Res Clin Pract. 2019;1(2):68–76.

SAMHSA. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2019; https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2019-nsduh-annual-national-report. Accessed 19 Mar 2021.

National Institute of Mental Health. Major Depression. 2019; https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml. Accessed October 15, 2020.

Joshi K, Zhdanava M, Pilon D, Lefebvre P, Sheehan JJ. Health care use and associated cost among patients with treatment-resistant depression across US payers: a comprehensive analysis. Poster presented at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) Annual Meeting; March 25–28, 2019; San Diego, California.

Kubitz N, Mehra M, Potluri RC, Garg N, Cossrow N. Characterization of treatment resistant depression episodes in a cohort of patients from a US commercial claims database. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e76882.

Li G, Fife D, Wang G. All-cause mortality in patients with treatment-resistant depression: a cohort study in the US population. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2019;18:23.

Cepeda MS, Reps J, Ryan P. Finding factors that predict treatment-resistant depression: results of a cohort study Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(7):668–73.

Gaynes BN, Asher G, Gartlehner G, et al. Definition of treatment-resistant depression in the Medicare population. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2018.

Conway CR, George MS, Sackeim HA. Toward an evidence-based, operational definition of treatment-resistant depression: when enough is enough. JAMA Psychiat. 2017;74(1):9–10.

Voineskos D, Daskalakis ZJ, Blumberger DM. Management of treatment-resistant depression: challenges and strategies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:221.

Parikh RM, Lebowitz BD. Current perspectives in the management of treatment-resistant depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2004;6(1):53.

Ionescu DF, Rosenbaum JF, Alpert JE. Pharmacological approaches to the challenge of treatment-resistant depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17(2):111–26.

Mrazek DA, Hornberger JC, Altar CA, Degtiar I. A review of the clinical, economic, and societal burden of treatment-resistant depression: 1996–2013. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(8):977–87.

Amos TB, Tandon N, Lefebvre P, et al. Direct and indirect cost burden and change of employment status in treatment-resistant depression: a matched-cohort study using a US commercial claims database. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(2):17m11725.

Pilon D, Sheehan JJ, Szukis H. Medicaid spending burden among beneficiaries with treatment-resistant depression. J Comp Eff Res. 2019;8(6):381–91.

Al-Harbi KS. Treatment-resistant depression: therapeutic trends, challenges, and future directions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:369–88.

Taylor RW, Marwood L, Greer B, Strawbridge R, Cleare AJ. Predictors of response to augmentation treatment in patients with treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(11):1323–9.

Zhdanava M, Kuvadia H, Joshi K. Economic burden of treatment-resistant depression in privately insured US patients with physical conditions. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(8):996–1007.

Zhdanava M, Harsh K, Joshi K, et al. Economic burden of treatment resistant depression in privately insured US patients with behavioral comorbidities. US Psych Congress; October 3–6, 2019, 2019; San Diego, CA.

Citrome L. A review of the pharmacology, efficacy and tolerability of recently approved and upcoming oral antipsychotics: an evidence-based medicine approach. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(11):879–911.

Citrome L, Johnston S, Nadkarni A, Sheehan J, Kamat AS, Kalsekar I. Prevalence of pre-existing risk factors for adverse events associated with atypical antipsychotics among commercially insured and Medicaid insured patients newly initiating atypical antipsychotics. Curr Drug Saf. 2014;9(3):227–35.

Park Y, Raza S, George A, Agrawal R, Ko J. The effect of formulary restrictions on patient and payer outcomes: a systematic literature review. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(8):893–901.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 45 CFR 46: pre-2018 requirements. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html#46.101. Accessed 16 Oct 2020.

Lafeuille MH, Patel C, Pilon D, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and economic burden of schizophrenia among Medicaid beneficiaries. Presented at Psych Congress2019; San Diego, California, USA.

Benson C, Szukis H, Sheehan JJ, Alphs L, Yuce H. An evaluation of the clinical and economic burden among older adult Medicare-covered beneficiaries with treatment-resistant depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;28(3):350–62.

American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder: third edition. 2010; https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Accessed 17 Oct 2019.

Citrome L, Nasrallah HA. On-label on the table: what the package insert informs us about the tolerability profile of oral atypical antipsychotics, and what it does not. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(11):1599–1613.

Austin P. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2009;38(6):1228–34.

Zhdanava M, Kuvadia H, Joshi K, et al. Economic burden of treatment-resistant depression in privately insured US patients with co-occurring anxiety disorder and/or substance use disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020:37(1):123–33.

Pilon D, Sheehan JJ, Szukis H. Is clinician impression of depression symptom severity associated with incremental economic burden in privately insured US patients with treatment resistant depression? J Affect Disord. 2019;255:50–9.

Peng M, Southern D, Williamson T, Quan H. Under-coding of secondary conditions in coded hosptial health data: impact of co-existing conditions, death status and number of codes in a record. Health Inform J. 2017;23(4):260–7.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, including the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees. The sponsor was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation, and publication decisions.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Maryia Zhdanava, Dominic Pilon, Carmine Rossi, Laura Morrison, and Patrick Lefebvre contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. Swapna Karkare, Kruti Joshi, John Sheehan, Oliver Lopena, and Leslie Citrome contributed to study conception and design, and data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript.

Prior Presentation

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the 2020 Virtual US Psych Congress, September 10–13, 2020.

Disclosures

Maryia Zhdanava, Dominic Pilon, Carmine Rossi, Laura Morrison, and Patrick Lefebvre are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript. Swapna Karkare, Kruti Joshi, John Sheehan, and Oliver Lopena are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC and stockholders of Johnson & Johnson. Leslie Citrome has received consulting fees from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC for the conduct of this study. In the past 12 months, Leslie Citrome has served as consultant: AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Astellas, Avanir, Axsome, BioXcel, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cadent Therapeutics, Eisai, Impel, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen, Karuna, Lundbeck, Lyndra, Medavante-ProPhase, Merck, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Ovid, Relmada, Sage, Sunovion, Teva, University of Arizona, and one-off ad hoc consulting for individuals/entities conducting marketing, commercial, or scientific scoping research; speaker: AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Eisai, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, Lundbeck, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, and CME activities organized by medical education companies such as Medscape, NACCME, NEI, Vindico, and Universities and Professional Organizations/Societies; owns stocks (small number of shares of common stock): BristolMyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, J & J, Merck, Pfizer purchased >10 years ago; and received royalties: Wiley (Editor-in-Chief, International Journal of Clinical Practice, through end 2019), UpToDate (reviewer), Springer Healthcare (book), Elsevier (Topic Editor, Psychiatry, Clinical Therapeutics).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All data are de-identified and fully comply with the patient confidentiality requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Per Title 45 of Code of Federal Regulations, Part 46.101(b)(4)23, the analysis of our study is exempt from institutional review for the following reasons: (a) it is a retrospective analysis of existing data with no patient intervention or interaction, and (b) no patient identifiable information is included in the claims dataset.

Data Availability

Data that support the findings of this study were used under license from IBM® Watson HealthTM. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which are not publicly available and cannot be shared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhdanava, M., Karkare, S., Pilon, D. et al. Prevalence of Pre-existing Conditions Relevant for Adverse Events and Potential Drug–Drug Interactions Associated with Augmentation Therapies Among Patients with Treatment-Resistant Depression. Adv Ther 38, 4900–4916 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01862-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01862-z