Abstract

The development of New Belgrade, initiated in the post-war period, was based on the Modernist concept of urban structure. The planned central zone was never built, but the local community places, as urban hubs for meeting and gathering, have been developed within the initially conceived open public spaces. Considering their importance for establishing and strengthening local communities, the article focuses on the development tendencies detected in emerging urban hubs of the residential Blocks 37 and 38. Unlike many other blocks of New Belgrade, which have been exposed to drastic changes of their original Modernist structure, their authentic setting have remained mostly intact since their construction in the 1970s. Therefore, they are selected as the examples of a new process of community planning which has followed the activities of place making. Triggered both by the changed patterns of use and the specificities of original spatial features, these changes also influence the local neighborhood while shifting the perception of the previously neglected open public spaces. The emerging hubs are analyzed on the level of networks, configuration and places, providing an insight into ongoing transformation of both the space and the local community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The main focus of the article is the phenomenon of new urban hubs generated within the existing open public spaces of the Modernist super-blocks in New Belgrade, a municipality of the Serbian capital Belgrade. Triggered by both the changed patterns of use and the specificities of their original setting, they have instigated the process of community planning, influencing the strengthening of local neighborhoods, their social and environmental awareness.

The global tendencies of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) highlight the importance of local communities in urban development, encouraging the bottom-up approach (PPS 2007; ICLEI 2015; Habitat III 2016). The members of a community use local gathering places for social, cultural or recreational purposes and, consequently, these places have a significant role in a community strengthening (American Heritage® 2011). Although frequently spontaneous, their development also represents a place making process and a collaborative action, based on the shared values of physical, cultural, and social identities which define a place (UN Habitat 2015). Considering these elements and new practices, the article reconsiders the role of open public spaces in the Modernist super-blocks as a valuable resource for both spontaneous and planned emergence of urban hubs. Serving as gathering places, they also represent the possible nuclei of social empowerment and activism, especially in challenging situations which might threaten the general well-being and environmental comfort of residents.

This topic is especially important in the context of post-socialist cities (Andrusz et al. 1996; Tsenkova and Nedović-Budić 2006; Stanilov 2007) and the delayed process of socio-economic transition reflected in urban space of Serbian cities (Vujošević and Nedović-Budić 2006; Petovar and Vujošević 2008; Blagojević 2009; Vasilevska et al. 2020). During the last two decades, the Modernist super-blocks in New Belgrade have developed new urban hubs using the existing open public spaces, often underused and neglected. Developed between 1945 and the 1980s, when the Belgrade metropolitan territory was rapidly expanding, these blocks were planned as mostly residential.

As the representative examples of urban hubs developed by both the spontaneous place making and the community planning, Blocks 37 and 38 were chosen due to their limited exposure to the drastic changes of their original structure. Minor changes within the open public spaces (both physical and functional) have been detected since the 1990s, although a growing (and justified) fear of aggressive transformations is currently present. In order to relate their main features with the ongoing place making processes and the occurring community planning, three main spatial elements were considered—networks, configuration and places/hubs. Embedded into the original structure of Modernist open public spaces, they have followed the dynamism of community needs, especially the intrinsic need of gathering. Therefore, urban hubs could be considered as a specific infrastructure for strengthening social capital (Woolcock 1999).

The article consists of six parts. After the introduction part, the theoretical background is provided, including a brief historical overview of the Modernist principles applied in the case of New Belgrade and the ongoing studies on community planning. The next section highlights the elements of methodological approach, which were applied in the fourth part, dedicated to the selected case studies. The discussion section considers the results of the analysis, emphasizing both the positive and negative development tendencies of emerging urban hubs, while concluding remarks summarize the findings, suggesting further development possibilities.

Triggering the change: toward the community planning

The historical background

New Belgrade is a very specific area between two old cores of Belgrade, where the Modernist paradigm was applied in accordance with the original idea of The City of Tomorrow—Le Corbusier’s vision of a futuristic city (1929). Conceived as a solution for rapidly growing cities, this concept also influenced the 4th CIAM conference (1933), resulting in the Athens Charter (Corbusier 1943).

According to the Modernist interpretation, open green spaces within spacious residential blocks were collective areas, representing the extensions of apartments. Although Le Corbusier described them as the lungs of a city, numerous authors stressed out the physical, functional and social weaknesses of this concept resulting in cold and impersonal spaces dominated by cars, lacking the vibrancy of traditional squares and streets (Jacobs 1961; Perović 1985; Trancik 1986; Alexander 2005; Gehl 2011). However, the period after the World War II created the fertile ground for the application of this concept in Europe, due to massive migrations to cities perceived as the new generators of war-damaged national economies. The Modernist concept enabled a higher quality of life for the rising urban population, especially in the rapidly expanding urban fringes. This process was also noticeable in ex-Yugoslav context, particularly in its capital Belgrade, where the municipality of New Belgrade was exposed to an intensive urban development since the 1960s (Fig. 1).

Although initially planned as a new administrative center of Yugoslavia, the limited funds postponed the implementation of the anticipated cultural, service and office spaces in the central zone, while focus shifted on housing. The character of New Belgrade was diverted from the original idea, creating so-called Big Dormitory, a settlement without basic urban services (Stojanović 1974). Since then, the population of Belgrade has increased more than five times, influencing the change within local communities—their structure, needs and, consequently, spatial identity (or lack thereof) (Đokić et al. 2016, 2018; Simić et al. 2017). The original planning paradigm was also adjusted to the needs of transitional post-socialist period, resulting in the transformation of the spatial structure of New Belgrade, in accordance with growing commercial and business activities (Petrović 2008).

There are several types of Modernist super-blocks used in Belgrade, but the ones originally applied in New Belgrade were the most similar to the initial idea of The City of Tomorrow. However, a few of them have preserved their original form (Fig. 2), while those creating the central zone of the area have been gradually transformed, in spite of being officially protected in January 2021. Since the 1990s, the’empty’ (i.e., unused) open public spaces of super-blocks have been occupied by commercial activities which were interpolated, especially in the central zone and along boulevards (Marić et al. 2010). The Big Dormitory became the Belgrade Business District, while the previously planned open public spaces, within drastically changed structures, lost their role of gathering places. Meanwhile, Blocks 37 and 38 had remained mostly intact—until recently.

Although ‘lost’ community spaces became very important due to the limitations imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., a lot of birthdays took place within the several urban hubs), the lack of official initiatives for their re-activation represents a serious obstacle for their community use. Furthermore, their (re)activation should tackle a number of issues regarding the awareness of changing needs and values, as well as the new imperatives of spatial and social integration and development.

The theoretical background

Although the open public spaces created within the Modernist super-blocks are often labeled as ‘lost spaces’ without traditional values, rethinking their management could enable a positive shift of general perception (Trancik 1986). Their urban design, based on the needs of users and their values, also represents the crucial development factor and the element of appreciation, often contested by and/or under pressure from different stakeholders (Madanipour 2010). The contemporary studies also emphasize the importance of organization and identification with the contemporary public spaces (Carmona 2010), while some authors underline the fact that public places should not be considered as individual components of the urban environment, but rather as a whole with the surrounding buildings, roads and open spaces (Tibbalds 2001). This approach contributes to the emergence of an urbanism which promotes social integration and tolerance (Madanipour 1999, 2003). Therefore, it is necessary to understand how a place works in order to make it better, and many successful examples confirm that short-term actions and visible changes conducted by communities could lead to positive effects (PPS 2000).

The problem of super-blocks, transition of their use and structure, as well as the (in)utility of their open public spaces have also been studied in Serbian context (Blagojevic 2014; Đokić et al. 2016; Milojević et al. 2019 etc.) revealing numerous problems generated by the changed socio-economic context and insufficiently developed collective awareness of both social and environmental issues, which reflected in spatial devastation and a serious lack of maintenance.

During the last 30 years, especially in the US and EU contexts, the need for including communities into planning process was recognized. Some authors emphasize that success and transformative power depend on a number of elements which have to ensure the sensitive, supportive, inquiring and carefully analytical nature of the process, which might be challenging but should not be directive or patronizing (Kennedy 1996; Community Places 2012). In general, the main goal of community planning is to establish collaboration between governmental structures and communities in order to improve social, economic and environmental well-being of communities within their physical neighborhoods (Crown Copyright© 2015; Blackson 2017). Community planning was considered as an important idea tackled by various studies conducted in Serbia, targeting the framework of collaboration (Lazarević-Bajec 2009), the integrative approaches to planning and design (Mrđenović 2010,2011,2014) and the role of participatory processes (Čolić 2014; Čolić and Dželebdžić 2018). The theme of place making and the sustainability of open public spaces—as new urban hubs and gathering nodes—has also become important for the planning practice, focusing on the issues of multi-functionality (Živković 2018), safety (Stanarević and Đukić 2014), the improvement of green infrastructure (Simić et al. 2017), real-time/space interaction and activism (Stupar et al. 2020) or the introduction of digital tools (Đukanović et al. 2004; Stupar et al. 2019).

Considering this, the selected cases of emerging urban hubs in New Belgrade will reveal the role and position of community planning in the overall process of transformation, targeting open public spaces inherited from the original Modernist framework.

Having all of this in mind, it should be highlighted that New Belgrade could still use the potential of open public spaces in mostly authentic blocks (e.g., Block 37 and 38) for strengthening communities within. Urban hubs and their place making represent one of the most important tools for achieving this aim. Also, community planning emphasizes the importance of collaboration between governmental structures and communities, but the main problem of New Belgrade is a non-transparency of governing system which inhabitants perceive as ‘the attack of profit’ (i.e., investors) which threatens their living environment. As a result of this process based on the neo-liberal logic, around 30 civil protests took place across Belgrade in June 2021. Since drastic changes of open public spaces can irrevocably transform the content and spatial comfort of super-blocks, only strong community interrelations can generate a social response which can stop or redirect invasive processes. Consequently, urban hubs have an important role in building community trust and generating power for a change.

Methodology

The analysis conducted in this article is based on the review of available documents—the Master Plan of Belgrade (GUP 1950,1972,1984,2003,2016); competition entries; detailed and regulation plans for Blocks 37 and 38 (Mišković 1974); the national Law on Planning and Construction (OGRS, 145/2014); and the 2011 and 2018 Belgrade Statistical Yearbook. The methods of observation and interviews were applied considering the development of urban hubs.

The observation was focused on the selected Blocks 37 and 38 and based on the Google Earth software. The qualitative data were collected through interviews with 60 inhabitants, which included a set of questions providing the basic data on interviewees (age, gender, parental status, profession, free-time activities), as well as the specificities of communities, activities, physical structure and safety. Only the residents of two selected super-blocks were interviewed. The gender structure (female/male) was approximately 55:45%.

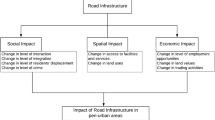

The spatial characteristics of public open spaces were examined according to the theoretical framework provided by Theory of social life of small urban spaces (Whyte 1980), Theory of the nature of order (Alexander 2005), Theory of integral urban design (Ellin 2006) and Theory of life between buildings (Gehl 2011). The focus was on three spatial levels (Norberg-Schulz 1990), targeting relevant elements listed in Table 1.

The network level describes the interconnections within the whole spatial system of hubs (Norberg-Schulz 1990; Alexander 2005; Ellin 2006). The frequency of path(s) indicates the permeability and connectivity, based on the observed daily motion of inhabitants toward/from the areas of influence, while the accessibility within the network reveals the areas with easy or limited physical approach.

The configuration level deals with the areas important for gathering (Norberg-Schulz 1990; Ellin 2006; Gehl 2011). The proximity to inhabitants (Gehl 2011) on a daily basis indicates the possibility for establishing certain activities. According to Gehl, a short and manageable routes between the private and the public environment (50 m) influence the connection between people and certain activities, as well as the opportunities for inhabitants’ involvement in activities, supplementing small, daily domestic routines. Meanwhile, the area of influence provides information on the spatial availability and capacity for certain activities, while its shape provides an insight into the possible/existing tendencies of further development. Consequently, frequency and variety of these activities within the area contribute to the importance of focal points and the radius of their impact.

The level of place (Norberg-Schulz 1990; Alexander 2005), i.e., an urban hub, considers several elements—seating capacity, as the most important one, as well as the presence of natural and protective elements and the presence of a table/focal point (Whyte 1980). Whyte empirically determined that one meter of sitting place substitutes eight square meters of the surface, while wind, sun and shadows create a greater variety of possibilities for the extended stay and activities of people. Furthermore, an appropriate focal point within the hub (e.g., table) also increases the possibilities for more intensive and extended use.

The case study: urban hubs in blocks 37 and 38

Basic units of Modernist structure could be defined as super-blocks since they are significantly larger than traditional urban blocks (Carmona et al. 2003). Their difference in size is the most obvious physical characteristic, but the most important difference is the way they function. The street is the most important spatial element for the development of social life in the traditional urban block, while within the super-block this role is carried by the open public space – the space between the high-intensity traffic routes and around buildings. The selected units of the Modernist urban structure of New Belgrade, Blocks 37 and 38, are the most similar to the original concept in terms of the basic structure (both physical and functional) Fig. 2.

However, the terminology describing Modernist structure of Belgrade has varied—the 1950 Master Plan used the term residential neighborhood, while Master plans from 1972 and 1984 used the name local community. Still, open public space represents the most important component of each unit (super-block) due to its physical and functional accessibility to all users. Therefore, it could be also perceived as a neighborhood of a local community (Brint 2001). However, the 2003 and 2016 documents used the term open block, triggering drastic transformations aiming at their unoccupied spaces, which later became mostly occupied by commercial activities (Marić et al. 2010). This process of questionable interpolation caused many other problems considering the lack of parking space, blocked apartment views or disturbed ecological comfort. In spite of the intensive changes in many New Belgrade areas, Blocks 37 and 38 have mostly preserved their original spatial characteristics (Jovanović and Đukanović 2019). They are surrounded by high-intensity traffic routes, with a local street between them (Fig. 3), while their open public spaces gradually included several urban hubs (including three selected for this case study).

The development of this area according to the Modernist concept started in 1966 (Mišković 1974). The residential buildings were built in 1970, as well as primary schools and nurseries, but the centers of local communities were not initiated until the 1980s. Since the 1990s, the inhabitants have become legal owners of apartments and the problem of maintenance of public or communal spaces has affected both the buildings and open spaces. Today, a half century after the construction of residential buildings, the urban parameters are drastically changed. For example, during the 1970s the degree of motorization was 0.7 vehicle/apartment (Mišković 1974), while today it reached 1.2 vehicle/apartment. Consequently, walking paths are nowadays partially occupied by cars, disconnecting certain spaces and activities. Cultural life is still underdeveloped, but the inhabitants have been more socially engaged through the spontaneously developed urban hubs.

Considering these processes, Tables 2 and 3 provide a comparison of physical and functional characteristics identified in (a) The City of Tomorrow (Corbusier 1987), (b) the Plan for the super-blocks within the New Belgrade region III (which included Blocks 37 and 38) (Mišković 1974) and (c) the current state of Blocks 37 and 38 based on observations. The symbol “*” in both tables marks the statements by Le Corbusier (1987) and Mišković (1974), while other data were obtained by the AutoCAD software, mathematical approximation or observation.

The gross area of Blocks 37 and 38 is 400mx400m, defined by the axes of surrounding traffic corridors/main streets. The calculation of physical indicators uses the net area of each block, considered to be more accurate. The data provided in Table 2 indicate that the selected Blocks 37 and 38 are very similar to the original idea. Even though the share of open spaces is relatively high, the anticipated standard is not achieved due to a higher number of inhabitants.

The summary of activities listed in Table 3 reveals that the current situation is different from the original concept, since the selected blocks include some necessary commercial contents, as well as the lower-intensity streets.

Urban hubs vs. community planning process: emerging elements

In the recent legally binding planning documents (GUP 2003, 2016), Blocks 37 and 38 are defined as open blocks with diverse activities (e.g., housing, commercial activities, public services, former local community centers, traffic and parking areas, public spaces), indicating that their further development should be based on the multifunctional use of higher intensity. The term ‘(open) public space’ refers to originally planned sports/recreational fields and playgrounds (see Table 3) and public green areas, representing the space where several urban hubs have emerged spontaneously. Considering this, an open public space can be described as a space between buildings, with a complex system of intertwining activities connected by paths. There were not significant changes between 1966 and 1990, and there were only a few punctual interventions until 2000. Until 2005, the major change was the finalization of the last part of the Boulevard of Milutin Milanković. Consequently, the open spaces in selected super-blocks were not radically affected and the successful development of several urban hubs has emerged (Fig. 4). Before the activation, the area currently occupied by hubs had included only open public spaces without particular function – green areas or cul-de-suc.

In 2005 the local community made a ‘bowling terrain’ in Block 38 (UH3—Figs. 5 and 6), while ‘four benches’ emerged circumstantially in Block 37 (UH2—Figs. 5 and 6). When Block 37 experienced intensive building process along the Boulevard of Milutin Milanković (2007–2009), the hub of ‘four benches’ also became a coffee-break place for the people working in new office buildings. Currently, the increasing number of cars is devastating this area due to the lack of parking lots.

In the following period there was an upgrading of an existing building in Block 38 (2014), while the central area of Block 37 was renovated (2016), reviving old playground and sport fields and upgrading spontaneously developed ‘Tables and benches’ (UH1—Figs. 5 and 6). In 2020, the part of open public space in Block 38, along the Boulevard of Milutin Milanković, became the site of an infrastructural project, annulling the potential for the further development of this open public space. The assumption is that the renovation of the existing park and sitting places around bowling terrain was conducted by the municipal government in order to (at least declaratively) mitigate the irreparable damage to this space and avoid the justified anger of the local community.

The situation presented in Fig. 4 indicates that the elements of community planning process for UH1 and UH3 could be identified only in the phase related to establishing the final structure of the hubs, while the development of UH 2 was spontaneously initiated by the community and based on its enthusiasm. However, this effort cannot be sustained for a long time without proper legal framework which would adequately channel the initiatives and energy embedded in community planning—as already proven by similar cases which eventually lost their momentum.

The spatial characteristics of the hubs

The spatial features of the Blocks 37 and 38 also influenced both the establishment of hubs and community initiative. Their impact (or lack thereof) on three observed levels is presented in Table 4.

On the network level it is evident that urban hubs appeared along frequent paths. They are easily accessible, without any obstacles. The assumption is that frequently used paths connect places with activities which gather/attract more people. It could be expected that every unoccupied space along frequent paths and near the area of influence could become a new urban hub in the future. However, some parts of the network could be less accessible to the certain groups of users due to existing barriers (cars, damaged pavement, etc.).

The configuration level of urban hubs could be described as convenient. The probability of the longer retention of residents is higher in the immediate vicinity of residential buildings. Although some activities also triggered the appearance of sitting places within their areas of influence, the selected urban hubs have been established and used without that kind of functional trigger, although in their close proximity. However, hubs are situated closer to residential units, with the only exception of UH3, which is positioned more than 50 m from the nearest building entrance.

The level of place, i.e., urban hub, indicates the ability to retain people. The capacities of the selected hubs differ, but they are complementary to surrounding activities. The main problem for determining the amount of sitting places is that the boundaries of each urban hub area are functionally and spatially blurred and can only be assumed. All of the urban hubs contain trees and public green spaces, but lack protective elements (canopies). As an element which triggers a variety of gathering activities, a table exists only in UH1 and partly in UH3. It would be convenient to introduce this element to UH2, even though a café emerged next to it.

The emerging challenges of neo-liberalism: block 37

The transitional period in Serbian economy has recently affected one of the selected super-blocks—Block 37. In the beginning of June 2021, along the Boulevard of Milutin Milanković, a fence emerged around an empty lot, which was previously used as a spontaneously created parking space, due to the increasing number of cars (Table 3). The local community was confused by sudden activities—the removal of trees and excavation, as well as the lack of any information regarding the transformation. After few days the info board appeared, showing a drawing of a huge office building (eight stories high and approx. 200 m long). A few days before the protest of local community started, the presentation of this project had also appeared on internet, revealing a number of contextual problems—from the position and exaggerated size to questionable circulation routes—which would severely affect the functionality and quality of life in the block (Fig. 7). Consequently, the residents named this building—‘The Monster’. One of the biggest problems would represent the newly anticipated number of cars (250–1000) which would affect the existing inner traffic, especially during the peak hours. The lack of parking space would increase further, causing the misuse of pedestrian streets, reducing accessibility to open public spaces (similar to the case of Block 38) and affecting traffic safety, especially for local children attending the primary school (Fig. 5).

Source: Authors. According to the information provided by https://ivastefanretail.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/PRESENTATION-BLOK-37-VARIANT_84840289616799889737.pdf?fbclid=IwAR1G-tGH2Rfs4I1p1IfPOO2mWSppsf6qyeLcKuCZD4_DdN1l6J7mzTH4trQ (accessed on June 3rd 2021)

The Monster building in the context - 3D visualization and section.

Consequently, the occurring protests represented the reaction of the local community to the insufficient transparency of the transformation process, which is the practice already noticed in the different areas of Belgrade. However, this initiative raised the attention of other local communities, revealing many similar situations and ‘plans’ they were unaware of.

The negotiation processes between city government, investor and the residents of Block 37 are still ongoing, but it should be noted that according to the Plan of General Regulation the critical site should be occupied by a three stories high building. Its construction would cause similar problems, but to a lesser extent. Therefore, the residents hope that the government might influence some changes in their favor, annulling the current planning documents and enabling the better quality of life.

Discussion

An integrated and inclusive community takes its shape through a complex system of relationships between human behavior and the ways of experiencing places and spaces (Madanipour 2011). The coherence between a city, its urban planning and architecture, neighborhoods and public places is very significant in these processes. The community planning process implies an official cooperation between local government and communities within a neighborhood, with an incremental approach to long-term processes (Esposito De Vita et al. 2016). Consequently, so-called ‘third places’, representing all the informal public places that people visit beyond housing and work, are of special importance for the social life of a neighborhood (Oldenburg 1999). These places should be accessible and open to all, regardless of their age, background, opportunity or social status. Due to that, they could be key nodes for social support, spontaneous encounters and community involvement. According to Oldenburg (1997), they could also serve as community centers, libraries, cafes, pubs and public parks, while their ideal location should be within a walking distance of a local neighborhood. The same author also underlines their role in uniting a neighborhood, while representing access points for visitors and new residents (Oldenburg 1997). These places/hubs could also attract people with common interests, providing the different kinds of social support, care and interaction on different topics (politics, environment, identity, equity etc.).

The selected cases of three urban hubs in New Belgrade represent the rudimentary modes of community planning process, supported by the municipal government only after the spontaneous development occurred. Recognizing the established gathering points around these urban hubs, the Municipality included their repair and maintenance into larger projects (e.g., playgrounds/parks in both blocks—UH1 and UH3), while the city utility company granted the requested street furniture to UH2. It should be also noted that the Municipality of New Belgrade has around 250.000 inhabitants and it is centrally governed, without any lower levels of (functional) government focused on neighborhoods. Although the so-called managers of residential communities represent a link to the local level, they mostly deal with the basic maintenance of a single residential building. Therefore, the lack of an interactive governing body on a neighborhood level, which would also consist of local residents, represents the main problem in initiating, conducting and implementing a successful community planning process.

However, with the support of modern technologies, it would be possible to establish similar modes of local government and management, which would function via small communities gathered around common issues—e.g., playground maintenance or collecting recyclable materials. Similar examples could be already found in other areas of New Belgrade, supported by digital channels and media—e.g., local groups 37 blok or FortyFives. Additionally, YouTube profile Blok Profil provides an insight into important discussions on everyday life and problems in local neighborhoods.

The digital platforms have also been used during the recent protests in Block 37 (e.g., Facebook), enabling the efficient and coordinated mobilization of local neighborhood. Still, it should be emphasized that the physical urban hubs, which were presented in this article, had a crucial role in the protest preparation. Acting as a common ground for everyday meetings of residents and their supporters, they represented the focal points of interaction, information exchange and transmission, as well as a unique platform for strengthening community awareness and cohesion.

Planning the development of a city is a dynamic and complex process, but it should not be exclusively profit-oriented. The Modernist urban structure of New Belgrade was based on specific rules, which differ from the ones applied in the traditional urban tissue. Therefore, its development should be adjusted both to its inherited qualities and the imperatives of sustainability. The latest activities undertaken by the local residents indicate that the importance of open public spaces has been recognized and appreciated, uniting them over the mutual cause of protecting the existing environmental comfort. Meanwhile, the urban hubs should continue their role in gathering people and enhancing their sense of belonging, while providing space for mutual empowerment and well-being.

Conclusion

The Modernist concept applied in New Belgrade is still exposed to post-transitional transformation, which is visible even in the case of selected Blocks 37 and 38, although on a smaller scale. Unfortunately, some other super-blocks have already lost their urban hubs, lacking an official administrative and financial support necessary for their sustainability. Therefore, the importance of local government and its active participation in community planning, as well as in the support of spontaneous positive changes, is evident for the implementation of the process.

However, the differentiation between neighborhoods will be strengthened during the periods of social and spatial shifts (Petrović 2008), while the expansion of ever-increasing commercial activities and the privatization of public spaces seems to be inevitable, even in New Belgrade. Therefore, it is necessary to decrease the risk of drastic transformations and prevent the social and ecological misbalance which might occur in urban space. Integrated planning approach (Ellin 2006), which includes local community, as well as the recent trends of urban resilience, ecological awareness and urban activism, should be considered as a part of upcoming strategies, targeting numerous problems imposed by the environmental, economic and social transition of contemporary society.

The cases of urban hubs in Blocks 37 and 38 could be, therefore, used as a basis for a better understanding of inherited spatial capacities and emerging needs, which could be interlinked and used for activating unoccupied open public spaces of super-blocks. Although defined by the current planning documents as a part of public green spaces, in reality they represent areas covered by grass and trees, which are partly unused or covered by infrequent walking paths and devastated and neglected plateaus. However, it is difficult to estimate the direction of their development and redesign until some spontaneous activity (e.g., the introduction of seating places) or, oppositely, the formal or informal deprivation of public areas/well-being triggers the process. These kind of spaces have a great potential for the application of community-based and situated design, driven by specificities of both local spaces and users. This approach to open public space of super-blocks would contribute to sustainable practices, stimulating interaction between context (structures, activities, actors) and design (methods and professionals), while understanding the process of participation as a mutual learning, effort and development (Simonsen and Robertson 2012; Wates 2000; Frandsen and Petersen 2014). The sense of place attachment and place identity also needs to be created and/or reinforced within the process of implementation of neighborhood activities in order to improve the general life of the community, as well as to further ensure and facilitate public participation in planning process (Manzo and Perkins 2006).

Considering all these changes and challenges in the space of New Belgrade, it could be concluded that urban hubs in Blocks 37 and 38 represent structural elements, interconnected with inherited open public spaces originally planned within each super-block. The activities conducted in open public spaces, both planned and spontaneous, contribute to community awareness, self-recognition and the overall social sustainability of urban space, challenged by the process of post-socialist transition. Therefore, further studies on the potentials and challenges generated by the processes in the open public spaces of Modernist super-blocks could reveal the new directions of re-creation and/or re-activation. Stimulating their flexibility and adaptability, as well as updating the design and use of emerging urban hubs, their social and environmental potential could be increased, improving the living comfort of the current and future residents.

References

Alexander, C. 2005. The nature of order - A vision of a living world (Vol. 11). Berkeley, California, United States: The Center for Environmental Structure.

American Heritage®. 2011. Dictionary of the English language, Fifth Edition. American Heritage®, http://www.thefreedictionary.com/community+center. Accessed December 2016.

Andrusz, G., M. Harloe, and I. Szelenyi, eds. 1996. Cities after socialism: Urban and regional change and conflict in post-socialist societies. Oxford: Blackwell.

Blackson, H. 2017. The 5 'Cs' of community planning. CNU, https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2017/10/19/5-cs-community-planning. Accessed February 2021.

Blagojevic, L.J. (2009) A free market landscape’. In:, Z., (ed.) Differentiated Neighbourhoods of New Belgrade, ed. Z. Eric. Belgrade: Museum of ContemporaryArt, 128–33.

Blagojevic, L.J. 2014. Novi Beograd: reinventing Utopia. In: Urban revolution now: Henri Lefebvre in social research and architecture, ed. Christian Schmid, Łukasz Stanek and Ákos Moravánszky, Ashgate.

Brint, S. 2001. Gemeinschaft revisited: A critique and reconstruction of the community concept. Sociological Theory 19 (1): 1–23.

Carmona, M., T. Heath, T. Oc, and S. Tiesdell. 2003. Public places—Urban spaces. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Ltd.

Carmona, M. 2010. Contemporary public space: Critique and classification, part one: Critique. Journal of Urban Design 15 (1): 123–148.

Christopher, A. 2005. The nature of order: The vision of a living world. Berkeley: Center for Environmental Structure.

Community Places. 2012. Community Planning Toolkit. Community Places, https://www.communityplanningtoolkit.org/sites/default/files/CommunityPlanning.pdf. Accessed February 2021.

Corbusier, L. 1987. The city of tomorrow and its planning, 164–181. New York: Dover publications, inc..

Corbusier, L. 1943. La Charte d’Athènes. Paris: La Librairie Plon.

Crown Copyright©. 2015. Community planning. Crown Copyright©, https://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/articles/community-planning. Accessed February 2021.

Colić, N. and Dželebdžić, O. 2018. Beyond formality: A contribution towards revising the participatory planning practice in Serbia. Spatium 39: 17–25

Čolić, R. 2014. Evaluation of the capacity development of actors within participatory planning process. Spatium International Review 31: 45–50.

Đokić, V., J. Ristić Trajković, D. Furundžić, V. Krstić, and D. Stojiljković. 2018. Urban garden as lived space: Informal gardening practices and dwelling culture in socialist and post-socialist Belgrade. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 30: 247–259.

Đokić, V., J. Ristić Trajković, and V. Krstić. 2016. An environmental critique: Impact of socialist ideology on ecological and cultural sensitivity of Belgrade large scale residential settlements. Sustainability 8 (9): 1–23.

Đukanović Z., Živković J., Lalović K. (2004). Developing ICT tools for public participation in public spaces improvement process - Public Art & Public Space (PAPS) Belgrade Pilot Project results. CORP 2004: Geo-Multimedia 04, meeting place for planners: proceedings of the 9th international symposium on information and communication technologies in urban and spatial planning and impacts of ICT on physical space: February 25–27, 2004 TU Vienna, 2004, 373–378.

Ellin, N. 2006. Integral Urbanism. New York: Routledge.

Esposito De Vita, G., C. Trillo, and A. Martinez- Perez. 2016. Community planning and urban design in contested places. Some insights from Belfast. Journal of Urban Design 21 (3): 320–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2016.1167586.

Frandsen, M.S., and L.P. Petersen. 2014. Urban Co-creation. In Situated Design Methods, ed. J. Simonsen, C. Svabo, S.M. Strandvad, K. Samson, M. Hertzum, and O.E. Hansen. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gehl, J. 2011. Life between buildings: Using Public Space. Washington: Island Press.

General Urban Plan of Belgrade – GUP. 1950. Belgrade: The Institute for Development Planning of the City of Belgrade.

General Urban Plan of Belgrade – GUP. 1972. Belgrade: The Institute for Development Planning of the City of Belgrade.

General Urban Plan of Belgrade – GUP. 1984. Belgrade: The Institute for Development Planning of the City of Belgrade.

General Urban Plan of Belgrade – GUP. 2003. Belgrade: The Institute for Development Planning of the City of Belgrade.

General Urban Plan of Belgrade – GUP. 2016. Belgrade: The Institute for Development Planning of the City of Belgrade.

Habitat III. 2016. New Urban Agenda. Habitat III. https://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/NUA-English.pdf. Accessed October 2018.

ICLEI. 2015. The importance of all Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for cities and communities. ICLEI, http://www.iclei.org/fileadmin/PUBLICATIONS/Briefing_Sheets/SDGs/04_-_ICLEI-Bonn_Briefing_Sheet_-_Cities_in_each_SDG_2015_web.pdf. Accessed September 2016.

Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage books.

Janić, M. 1971. Metodološki pristup planiranju gradskih centara. Urbanizam Beograda 13–14 (11–13): 32.

Jovanović P. and Đukanović Z. 2019. Belgrad’s dreams and nightmares. In Conference proceedings of the 2nd international forum on architecture and urbanism Pescara, Italy, ed. Pignatti, L., Rovigatti, P., Angelucci, F., Villani, M. Roma: Gangemi Editore spa, 784–791. ISBN: 978–88–492–3667–5

Kennedy, M. 1996. Transformative Community Planning: Empowerment Through Community Development. Planners Network, https://www.plannersnetwork.org/case-studies-and-working-papers/transformative-community-planning-empowerment-through-community-development/. Accessed February 2021.

Kostić, K. 1984. General urban plan of Belgrade. Belgrade: The Institute for Development Planning of the City of Belgrade.

Lazarević-Bajec, N. 2009. Rational or collaborative model of urban planning in serbia: Institutional limitations. Serbian Architectural Journal, No. 2: 81–106.

Madanipour, A. 1999. Why are the design and development of public spaces significant for cities? Environment and Planning b: Planning and Design 26 (6): 879–891.

Madanipour, A. 2003. Public and private spaces of the city. London: Routledge.

Madanipour, A., ed. 2010. Whose public space?: International case studies in urban design and development. London: Routledge.

Madanipour, A. 2011. Social Exclusion and Space. In The City Reader, ed. R.T. LeGates and F. Stout, 186–194. London: Routledge.

Manzo, L., and D. Perkins. 2006. Finding common ground: The importance of place attachment to community participation and planning. Journal of Planning Literature 4 (20): 335–350.

Marić, I., A. Ninković, and B. Manić. 2010. Transformation of the New Belgrade urban tissue: Filling the space instead of interpolation. Spatium 22: 47–56.

Milojević, M., M. Maruna, and A. Đorđević. 2019. Transition of collective land in modernistic residential settings in New Belgrade. Serbia. Land 8 (11): 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8110174.

Mišković, J. 1974. III Stambeni Rejon. Urbanizam Beograda 25: 22–23.

Mrđenović, T. 2010. Report from the workshop: participative approach in the shaping of Bač Fortress and its suburbium's open space, University of Belgrade - Faculty of Architecture. Belgrade: University of Belgrade - Faculty of Architecture.

Mrđenović, T. 2011. Integrative urban design in regeneration - principles for achieving sustainable places. Journal of Applied Engineering Science, 9(2): 305–316

Mrđenović, T. 2014. Teaching method: ‘Integrative Urban Design Game’ for soft urban regeneration. Spatium International Review, No. 31: 57–65.

Norberg-Schulz, C. 1990. Stanovanje - stanište, urbani prostor, kuća. (M. Višnjić, M. Dodić, O. Arsenijević, Eds., M. Oda, & N. Karapešić, Trans.) Beograd: Građevinska knjiga.

Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, No. 145/2014. https://www.aers.rs/FILES/Zakoni/Eng/EnergyLaw%20SG%20145-14.pdf. Accessed January 2020.

Oldenburg, R. 1997. Our vanishing ‘Third Places’. Planning Commissioners Journal, 25 (Winter 1996–1997), 6–10.

Oldenburg, R. 1999. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community. New York: Marlowe & Company.

Perović, M. 1985. Lesons of the past. Belgrade: The Institute for Development Planning of the City of Belgrade: 26.

Petovar, K., and M. Vujošević. 2008. Koncept javnog interesa i javnog dobra u urbanističkom i prostornom planiranju. Sociologija i Prostor 179 (1): 24–51.

Petrović, M. 2008. Istraživanje socijalnih aspekata urbanog susedstva: Percepcija stručnjaka na Novom Beogradu. Sociologija 50 (1): 55–78.

Project for Public Spaces. 2000. How to turn a place around: A handbook for creating successful public spaces. Project for Public Spaces.

Project for Public Space (PPS). 2007. What is Placemaking?. PPS, http://www.pps.org/reference/what_is_placemaking. Accessed July 2016.

Simić, I., Stupar, A., Đokić, V. 2017. Building the green infrastructure of Belgrade: the importance of community greening. Sustainability 9/7(1183): 1–16, https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071183.

Simonsen, J., and T. Robertson, eds. 2012. Routledge international handbook of participatory design. New York: Routledge.

Stanarević S., Đukić A. 2014. Planning and designing safe and secure open public spaces in Serbia. Places and Technologies 2014 [Elektronski izvor]: keeping up with technologies to improve places: conference proceedings: 1st international academic conference, Belgrade, pp. 118–129

Stanilov, K. 2007. The post-socialist city: Urban form and space transformations in central and Eastern Europe after socialism. Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media.

Stupar, A., V. Mihajlov, K. Lalović, R. Čolić, and P. Petrović. 2019. Participative placemaking in Serbia: The use of the limitless GIS application in increasing the sustainability of universal urban design. Sustainability 11 (19): 5459. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195459.

Stupar, A., P. Jovanović, and J. Ivanović Vojvodić. 2020. Strengthening the social sustainability of super-blocks: Belgrade’s emerging urban hubs. Sustainability 12 (3): 903. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030903.

Tibbalds, F. 2001. Making people friendly towns: Improving the public environment in towns and cities. Spon Press.

Trancik, R. 1986. Finding lost space: Theories of urban design. New York: Wiley.

Tsenkova, S., and Z. Nedovic-Budic, eds. 2006. The urban mosaic of post-socialist Europe. Heidelberg; New York: Physica Verlag.

UN-Habitat. 2015. Habitat III issue papers: 11-public space. UN-Habitat workshop report, April, http://unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Habitat-III-Issue-Paper-11_Public-Space-2.0.compressed.pdf. Accessed July 2016.

Vasilevska, L., J. Zivkovic, M. Vasilevska, and K. Lalovic. 2020. Revealing the relationship between city size and spatial transformation of large housing estates in post-socialist Serbia. J. Hous. Built Environ 35: 1099–1121.

Vujošević M. and Nedović-Budić Z. 2006. Planning and societal context—The case of Belgrade, Serbia. In: Tsenkova S., Nedović-Budić Z. (eds.) The urban mosaic of post-socialist Europe. Contributions to Economics. Heidelberg; New York: Physica Verlag.

Wates, N. 2000. The community planning handbook: How people can shape their cities, towns, and villages in any part of the world. London: Earthscan.

Whyte, W.H. 1980. The social life of small urban spaces. New York: PPS.

Woolcock Michael, N.D. 1999. Social capital: Implications for development theory, research and policy, world bank research observer, pp. 1–49.

Živković, J., Lalović, K., Milojević, M., Nikezić, A. . 2019. Multifunctional public open spaces for sustainable cities: Concept and application. Facta Universitatis, Series: Architecture and Civil Engineering 17 (2): 205–219.

Acknowledgements

The paper represents the part of the research project “Spatial, Environmental, Energy and Social Aspects of Developing Settlements and Climate Change—Mutual Impacts” (36035), financed by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Serbia (2011–2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Special Issue: Balkans Special Issue.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jovanović, P.R., Stupar, A.B. The emerging community planning in the super-blocks of New Belgrade. Urban Des Int 27, 275–287 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-021-00169-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-021-00169-3