Abstract

Challenging student behavior can have negative consequences for both educators and students. Although effective behavior management strategies can improve student behavior, they are not consistently implemented with fidelity. The purpose of this exploratory mixed-methods study is to investigate which resources educators and other school personnel use to find information on effective behavior management strategies and their perceptions of those resources. We surveyed 238 educators in four West Virginia counties regarding the degree to which they used, trusted, could access, could implement, and could understand information regarding behavior management strategies on six types of resources (i.e., search engines, internet media, professional organization websites, journals, colleagues, and professional development). Ten participants shared additional insights regarding why educators prefer specific resources and what they searched for in behavioral resources in follow-up interviews. Results indicated that educators primarily used colleagues because they provide information perceived to be accessible, understandable, trustworthy, and usable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Challenging student behavior, such as noncompliance, aggression, and being off-task, has detrimental effects on both students and educators. Such behavior has been linked to decreased academic achievement, increased encounters with the juvenile justice system, and student drop-out (Gage & Macsuga-Gage, 2017; Noltemeyer et al., 2015; Rausch & Skiba, 2004). In addition, challenging student behavior is among the top causes of teacher burnout and attrition (Brunsting et al., 2014; Garwood et al., 2018). Issues related to behavior management are not restricted to special education, because most educators report working with students who display challenging behaviors in their classrooms (Reinke et al., 2011; Westling, 2010). As such, it is imperative that all educators implement effective behavior-management practices. It may be especially important that educators use highly effective behavior-management practices when teaching students with special needs, as this population is most at risk for academic failure, school drop-out, and expulsion (Bradley et al., 2008; Vaughn & Dammann, 2001).

Effective behavior-management practices have been shown to increase appropriate student behavior, engagement, and, ultimately, academic achievement (Scott, 2017; Simonsen et al., 2008). Unfortunately, the majority of educators report not having received adequate training on effective behavior-management practices and feel unprepared to handle challenging behaviors (Freeman et al., 2014; Gable et al., 2012). In fact, research suggests that educators are not implementing research-based practices consistently or with fidelity (Burns & Ysseldyke, 2009; Gage et al., 2017; Hirn & Scott, 2014), and frequently use some instructional and behavioral practices not supported or even disproved by research (Mostert, 2010). This research-to-practice gap is concerning because in general implementing research-based practices improves student outcomes, and their absence may have negative implications for students and educators. Therefore, it is imperative that all students, and especially those who have or are at-risk for disabilities, be taught by educators who utilize research-based behavioral practices in their classrooms (Cook et al., 2016; Simonsen et al., 2008).

Carnine (1997) posited that efforts to bridge the research-to-practice gap would be stymied if educators perceive research evidence as untrustworthy, inaccessible, or unusable. Trustworthiness is the level of confidence educators have in research evidence. Carnine speculated that educators commonly view research as untrustworthy because of the controlled conditions in which many studies are conducted and the academic jargon found in many research articles. Boardman et al. (2005) found that many educators did indeed mistrust research. Educators have expressed that they tend to trust the information provided by colleagues (i.e., practice-based evidence) rather than evidence from research studies (Beahm & Cook, 2021; Boardman et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2010).

Carnine’s (1997) second factor, accessibility, refers to how easily educators can find and interpret evidence regarding instructional practices. Carnine highlighted the difficulties educators may experience when finding and deciphering research reports (see also Vanderlinde & van Braak, 2010). Hudson et al. (2016) found that educators and administrators had difficulty accessing journal databases to retrieve research and, many times, were unaware of how to obtain access to research. Moreover, most teachers do not have advanced training in research and statistics and may experience difficulties in interpreting research studies.

Carnine’s (1997) third factor is usability, which refers to the practicality of instructional information, and whether educators feel they can implement the practice based on the information provided. Carnine explained that research reports rarely describe how to implement the targeted practice in a classroom. Landrum et al. (2007) reported that educators found personal sources (e.g., a colleague) more usable than data-based sources (e.g., research in a journal article) when reading about instructional practices. Likewise, Smith et al. (2010) found that educators reported finding information from other educators more usable than information from a journal article. In sum, many educators do not find research trustworthy, accessible, or usable but appear to perceive instructional information from colleagues as more trustworthy, accessible, and usable.

With the advent of the internet, social media platforms (e.g., Pinterest and Teachers Pay Teachers) have given educators access to colleagues outside of their own schools. Perhaps because educators appear to find information from other educators trustworthy, accessible, and usable, emerging research suggests that many educators may be using social media platforms such as Teachers Pay Teachers and Pinterest to get information on instructional practices (Opfer et al., 2016). However, little is known about where educators are going to find behavior-management practices to support students who display challenging behavior.

The purpose of this study is to investigate which resources educators and other school personnel use to find information on effective behavior-management practices and the degree to which they find these resources to be usable, trustworthy, understandable, implementable, and accessible. We measured two different aspects of usability by asking educators how much they could (1) implement and (2) understand the information found on each resource. We used an explanatory sequential mixed methods design that involved collecting quantitative data first, then collecting in-depth qualitative data to help explain the quantitative results (Creswell & Clark, 2017). In the first part of the study, quantitative survey data was collected and analyzed. The qualitative phase (focus-group interviews) was then conducted as a follow-up to the quantitative survey to help explain the survey results. The research questions for this study are:

-

1.

What resources do educators report using first when faced with behavior-management challenges?

-

2.

To what degree do educators report regularly using behavior-management resources, and to what degree do they perceive information from these resources as trustworthy, accessible, understandable, and implementable?

-

3.

Do educators report using some resources more than others to address challenging behaviors?

-

4.

What are teachers’ perceptions of high-quality behavior management resources?

-

a.

Why do teachers prefer colleagues?

-

b.

What do teachers look for in an online behavior-management resource?

-

c.

Where are teachers spending money on the internet, and why?

-

a.

Method

We utilized an explanatory mixed-methods design (Creswell & Clark, 2017) to examine our research questions. First, we collected quantitative data in the form of a survey. Then we collected qualitative data from focus groups with a subgroup of survey participants to deepen our understanding of the survey results.

Participants

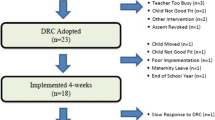

After receiving institutional review board approval, we asked six superintendents of county-level school districts from southwestern West Virginia to participate in the study. Four superintendents agreed to send the survey to professional personnel (i.e., teachers, principals, assistant principals, instructional guides, and speech therapists) in their districts. Following Dillman et al.’s (2014) recommendations, we sent an initial email to all 1,917 professional personnel in these four counties that explained the study and what participation entailed, provided information on informed consent, and included a secure link to the Qualtrics survey. We sent follow-up reminder emails after 1 and 2 weeks.

We received surveys from 238 respondents, resulting in a return rate of 12.43%. As shown in Table 1, most participants were white, female, taught in a general education classroom, taught in a Title-1 school, and had education beyond a master’s degree. Fifty-nine percent of the participants reported teaching in a general education setting, 20% taught in a special education environment, and 20% taught in other environments. Six administrators, five instructional coaches, five Title-1 teachers, four speech-language pathologists, four counselors, three social workers, two homebound teachers, and one librarian reported working in “other” environments. Fifteen of the “other” respondents taught in what could be considered a general education setting (e.g., art, music, career, and technical), whereas four indicated they taught in environments that could be considered a special education setting (e.g., self-contained special education classroom, autism classroom). Some of the respondents selected “other” but did not provide details regarding their teaching environment. Teaching experience ranged from 1 to 41 years, with an average of 14.29 years, with a relatively even distribution of respondents across grade levels. The average school size was 565 students (range = 110–1,900).

At the end of the survey, we invited respondents to participate in a focus group session. Survey respondents could click on a link that directed them to a google doc to provide their email address to be contacted about participating in a focus group. Ten individuals volunteered and ultimately participated in the focus group sessions. Eight of the participants were public school teachers, one was an administrator, and one was a school counselor. All focus group participants were white, and seven were females. Five of the teachers were teaching at the elementary level (three were special education teachers), and two were middle-school teachers.

Survey Development

To develop the survey, we asked a convenience sample of five currently practicing teachers (who did not participate in the survey) to list resources they frequently used to find behavior-management practices. Multiple teachers stated they used Teachers Pay Teachers, Pinterest, YouTube, teacher podcasts, teacher blogs, Google, information from professional development (PD) training, and textbooks. We chose not to include blogs and podcasts as resources on the survey because teachers indicated they found those resources via Pinterest or by using a search engine. We added (1) professional and academic journals and (2) professional websites (e.g., Intervention Central, IRIS Center) to our list because these resources are designed to bridge the research-to-practice gap and provide educators with information on research-based behavioral practices, and we were interested in educators’ perceptions of them. Two other teachers (who did not participate in the survey) and two special education professors reviewed the draft version of the survey. They provided feedback regarding clarity, language, and the possibility of survey fatigue, which informed the survey’s final iteration.

Survey respondents were asked how regularly they used eight resources (i.e., search engines [e.g., Google], Teachers Pay Teachers, Pinterest, professional websites, YouTube, professional and academic journals, colleagues, and PD training) to find information on addressing challenging and/or disruptive behaviors, as well as the degree to which they could trust, access, implement, and understand information from each resource. In particular, we asked participants to rate their agreement with each of the following statements on a 5-point Likert scale, from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) for each resource:

-

I regularly use [the resource] to find information on addressing challenging and/or disruptive behaviors.

-

I trust information found on [the resource] for addressing challenging and/or disruptive behavior.

-

I can easily find relevant information on [the resource] for addressing challenging and/or disruptive behavior.

-

I can easily understand the information found on [the resource] for addressing challenging and/or disruptive behavior.

-

I can easily implement the information found on [the resource] for addressing challenging and/or disruptive behavior.

The survey also included eight demographic questions and four contextual questions regarding challenging behaviors (e.g., I feel prepared to deal with challenging and disruptive behaviors in my classroom). An open-ended question was also asked at the beginning of the survey to identify what resource respondents first use when faced with a behavior challenge that their initial efforts to manage were unsuccessful. Finally, to triangulate and expand on participants’ ratings of their use of various internet resources, we also asked respondents if they downloaded teaching materials from the internet and, if yes, how much money they spent in the previous year. The question regarding money was included because instructional materials can be downloaded for free or for a fee from many internet resources. As such, we wanted to understand if teachers downloaded materials and how much they spend doing so.

Focus Group Development

Twenty individuals expressed initial interest in the focus groups and were sent emails requesting dates and times convenient for them to participate. Ten individuals responded to these emails, and we created two focus group sessions. One session had three participants, and the other had six. Research suggests that small focus groups provide valid qualitative data (Kitzinger, 1995; Morgan & Spanish, 1984). One individual could not meet during either selected focus group time, so they were interviewed individually. As these sessions were conducted at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, both focus groups and the individual interview took place via Zoom. Given the study’s explanatory mixed-methods design (Creswell & Clark, 2017), focus group questions were developed after we had reviewed the survey results and were guided by Carnine’s (1997) conceptual framework. The interviews were semi-structured, with primarily open-ended questions and probes used for follow-up comments and questions (Merriam, 2009). Focus-group questions explored (1) where teachers searched for behavior-management resources and why; (2) what, if any, external support they currently had access to when dealing with challenging behavior (e.g., administrators, board certified behavior analysts) and why they felt supported by that external support; (3) what they wanted in an online resource; and (4) on what resources they thought teachers were spending money. The lead author conducted the focus group discussions and each lasted approximately 40 min.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to answer the first and second research questions. Because Teachers Pay Teachers, Pinterest, and YouTube are all internet resources not associated with professional education organizations, we created an Internet Media variable representing mean respondent ratings for these three resources, resulting in six resources being analyzed. Cronbach’s alpha across the five rating items for the six resources ranged from .85 to .95, indicating a high degree of consistency across participants’ perceived use, trust, findability, understandability, and implementability for each resource. We used a one-way repeated measures ANOVA to examine the third research question of whether differences exist among educators’ use of six resource categories. We used follow-up pairwise comparisons to examine whether educators reported different frequency of use between specific resources.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Audio recordings of each session were transcribed verbatim by the lead author. The first author undertook the first stage of coding, which involved a close reading of the transcripts with words or phrases coded into themes. Carnine’s (1997) framework was used to develop the first stage of codes and possible themes, as well as to select which relevant quotes to highlight. The second step included reviewing, reducing, and organizing codes by category to establish patterns within and between groups. In the final step, salient themes were derived from recurring codes across categories (Krueger, 2014; Rabiee, 2004). Next, the third author reviewed the transcripts and codes to check for accuracy. Interobserver agreement (IOA) was calculated by dividing the total number of codes minus the disagreements by the total number of codes (65%). Disagreements were then reviewed and discussed until agreement was reached. Finally, participants were invited to review and evaluate the final summary of themes to ensure the researchers’ interpretation reflected their reality (Creswell & Poth, 2016; Thomas, 2006). Participants were asked to agree or disagree with the presentation of the themes and to provide further explanations to clarify their perceptions (all agreed and did not provide further explanations).

Results

Quantitative Results

To provide context regarding survey respondents, Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations of participants’ responses to the four quantitative items examining educators’ perceptions related to challenging behaviors. The table shows that 72.99% of the educators somewhat agreed or agreed that their students exhibited challenging and disruptive behaviors; 80.17% somewhat agreed and agreed that they felt prepared to manage students’ challenging behaviors; 65.55% somewhat agreed or agreed that they had access to the resources that supported them in managing challenging behaviors; and 78.90% somewhat agreed or agreed that they would like to access more high-quality behavioral resources. In addition, 89.49% of the educators responded that they downloaded material related to teaching and instruction from the internet in the past year. Finally, 58.82% reported they paid for downloaded teaching material in the past year, with the amount of money spent ranging from US$5–$1,000 (M = $150).

Before the survey questions, participants responded to an open-ended question asking them to identify the first resource they used to get information about addressing challenging behavior. Respondents identified colleagues (n = 100); administrators (n = 30); internet (n = 24); school counselors, school psychologists, behavior specialists, and social workers (n = 31); parents (n = 16); the student’s individualized education plan or behavior support plan (n = 6), and other resources (n = 31; e.g., discussion with the student or school-wide behavior programs).

As reported in Table 3, participating educators’ reported use and perceived trustworthiness, accessibility, understandability, and implementability of information varied by resource. In general, participants perceived colleagues, journals, PD sessions, and search engines positively. Ninety-one percent of participants strongly or somewhat agreed that they regularly used information from colleagues to address students’ challenging and disruptive behaviors. The most positive perception regarding colleagues was understandability of information; 92% strongly or somewhat agreed that information from colleagues was understandable. Participants felt positively regarding all attributes of information from colleagues. Sixty-four percent of respondents strongly or somewhat agreed that they regularly used information from professional and academic journals. The most positive perception of journals was trustworthiness (71% strongly or somewhat agreed), and the highest level of disagreement was for implementability of relevant information (9% strongly or somewhat disagreed). Fifty-six percent of respondents somewhat or strongly agreed that they regularly used information from PD sessions. Whereas 63% somewhat or strongly agreed that they could understand information from PD, 20% somewhat or strongly disagreed that it was easy to find relevant information from PD sessions. Fifty-one percent of participants somewhat or strongly agreed that they regularly used information using search engines such as Google. Whereas 62% strongly or somewhat agreed that the information from search engines was understandable, 20% of respondents strongly or somewhat disagreed that they trusted information from search engines.

Perceptions regarding information from professional websites and internet media (i.e., Teachers Pay Teachers, Pinterest, and YouTube) were more neutral. Only 27% and 8% of respondents somewhat or strongly agreed that they regularly used professional websites and internet media, respectively. The majority of respondents neither agreed nor disagreed that information from both resources was trustworthy, findable, understandable, and implementable.

Respondents’ use ratings differed across the six resource categories, F(5, 1170) = 120.74, p < .001. Follow-up pairwise comparison results, provided in Table 4, show that respondents agreed that they used colleagues as a source for information for behavior management significantly more than all other sources. Ratings of regular use were significantly lower for professional websites and internet media than all other sources (but were not different from one another). The reported use of search engines, journals, and PD did not differ significantly.

Qualitative Results

Focus group participants were asked why they chose a particular resource and what they wanted in an online resource. Themes were developed a priori based on Carnine’s (1997) framework and the survey results.

Theme 1: Understandability

We defined understandability as any response related to educators’ ability to interpret and understand the resource, including guidance for implementing the practice (e.g., a checklist of critical elements) and the ability to ask clarifying questions. Educators preferred resources that included familiar language that did not require further explanation. One participant suggested, “Make sure [the resource] uses simple language, not a lot of technical terms. If there are technical terms, they need to be explained.” Another participant indicated, “[The resource] doesn’t need to have a bunch of buzzwords because we already know those. Say it in plain English so we can read it and understand it quickly.” Eight participants either stated or agreed with the notion that resources should be free of academic jargon.

In addition, participants wanted resources to provide exact details on implementing the practice that included simple steps to understand the content better. One participant said, “It’s helpful to have an example, picture, or even a video.” Another participant noted, “Mostly having an example that is written within the text is helpful to see how it was specifically applied. [It is nice to] have a narrative to see how [the practice] was used with a student.” Another stated, “It would be nice to see, here’s what you do for the first week, second week, etc., and provide a step-by-step guide to implementing [the practice] in your classroom.” Five participants agreed that they would like to “see [the practice] in action” or have a detailed step-by-step guide.

Moreover, participants found colleagues to be their preferred resource because of how easy it is to understand their colleagues’ explanations of recommended practices. They also mentioned that colleagues provided clear descriptions of practices and offered continued support. One participant explained, “If you have questions or you’re trying to do something, it’s really easy to go back [to the colleague] and ask more questions [so you can understand the practice better].”

Finally, participants also wanted resources to be simple and straightforward in order to understand the material quickly. One participant stated, “Sometimes you can read all these research articles on what’s best, but it’s really hard to figure out what you need to do. I need it quick and easy. I don’t have time to figure out what it means.” Likewise, another explained, “[The resource] has got to be straight to the point, or I’m not going to read it.” Overall, participants wanted resources that clearly explained critical information using a common vocabulary that included a detailed guide to implementing a practice.

Theme 2: Accessibility

We defined accessibility as responses related to educators’ ability and ease of accessing resources, including finding resources for their particular situation (e.g., finding a practice for a second grader who is off task during math). Participants wanted resources that are easy to find, are simple to navigate and provide the necessary information efficiently. One participant stated they want a way to filter through information to see what was relevant quickly, and five participants agreed with this statement. In addition, participants wanted to be able to quickly make adjustments so the practice could easily be adapted to their needs. One suggested,

If [the resource] had a drop-down menu of options (e.g., a filtering system) [that allowed you to filter through] what happened, when did [the behavior] happen, did it happen when [the student] was triggered. It would give you options that might work for this child.

Another participant said, “It would be useful if there was an app where I could plug in the problems that I’m having, and the app could generate, not only potential things that we could try, but the supporting documents to go with it.”

One participant commented how convenient printable items are by saying, “Printables, it’s about speed. It’s about getting on [the website] and getting off of there.” Not only did the participants want documents to print off, but the materials needed to be appropriate for their environment. One special education teacher explained that printable resources would need to be “specific to the population that I’m working with.” Overall, teachers wanted filtering systems that provided practices specific to their problems that could be quickly tailored to fit their unique needs and include printable sheets for data collection.

Theme 3: Trustworthiness

We coded responses as trustworthy if they related to trusting the effectiveness and appropriateness of recommended content (e.g., colleagues know my students well), including practice-based evidence (e.g., it’s worked for them before), and confidence that recommended practices are appropriate or effective for their students. Participants found practices that were supported by practice-based evidence trustworthy. Practice-based evidence is generated in real classrooms with real teachers (Beahm & Cook, 2021) and therefore is perceived as trustworthy by many educators. Six participants mentioned going to colleagues because their colleagues provided them with practices proven successful for the student. For example, one participant said, “I go to the prior teacher or the counselor because they understand and have prior experience.”

Likewise, teachers valued recommended practices that had been successful with other teachers and students. One participant stated, “[Colleagues] are only going to tell you stuff that they’ve tried, and it’s worked,” while another explained, “[My colleagues have] a good track record,” and one more said, “It’s [a practice] that has worked for them.”

Participants also preferred colleagues because they had intimate knowledge of classrooms and students. For example, one indicated, “[Colleagues] know my students, and they understand what I’m asking for and who I’m asking for.” Another noted,

[Colleagues] will ask you questions like, “what is the student doing” and “what do you need help with specifically,” so it kind of narrows down what your plan is instead of typing in a general what they did wrong and hoping that you get some good stuff like in a book or online.

Overall, educators found their colleagues trustworthy because they understood the situation, answered questions, and their suggested practices are supported by practice-based evidence.

Theme 4: Usability

Like the previous themes, teachers want resources to provide information that is easy to implement. To distinguish understandability from usability, we defined the latter as responses related to the feasibility of using recommended content, including implementing the practice independently. Six of the participants mentioned the need for quick and easy data collection. For instance, one stated, “data tracking has got to be simple.” Another participant suggested that it would be easy if teachers could input data into an app that was uploaded to a website that automatically graphed it. Also reflecting the notion of ease of use, one participant said,

I want [a resource] that allows me to tick off (i.e., collect behavioral data) what the student does, have [the resource] generate a plan, and collect data all from the same location. I want to be able to put it in an app and have the teacher input information and have this resource gather data, keep track of it, and continue to build a plan. Then I can print out a behavior plan [based on this information].

Others stated the desire for resources to provide editable documents so they can efficiently adapt the materials. As indicated by one participant, “It would be nice to have a printable, but also an editable documentation sheet that you can go through and tweak it to your needs.” When one participant was discussing an online resource they preferred, they said,

[The website] is very easy. It’s very robust. It’s got a lot of options. It’s very flexible, and I like the flexibility of it. I don’t want to hear the history of the practice. Just tell me how to do it. Just fix [the problem].

In response to the question of where teachers spend money on instructional, all participants stated they used Teachers Pay Teachers because of how quick and simple it is to use. One participant explained, “Teachers love Teachers Pay Teachers, and you can’t get them to stop. Teachers go to Teachers Pay Teachers because of usability. It’s easy to use; it’s easy to understand. It’s in a language they understand. It’s usable and user-friendly.” One participant mentioned that their school had purchased PowerPoints from Teachers Pay Teachers for an entire grade to go along with a language arts unit to save teachers time and effort. Overall, teachers found resources usable when the resource was quick, efficient, and made their job easier.

Discussion

Many educators report feeling unprepared to handle challenging student behavior and have not received adequate behavior-management training to support their students (Gable et al., 2012). This lack of preparation may lead to educators seeking out behavior-management resources on their own. Previous studies suggest that educators are primarily utilizing colleagues as instructional resources (Boardman et al., 2005) as well as websites like Pinterest and Teachers Pay Teachers (Opfer et al., 2016). However, little research has examined what resources educators use to inform their behavior and classroom management or why they use those resources. Therefore, the main purpose of this study was to investigate which resources educators use when facing classroom and behavior management challenges, their perceptions of those resources, and why they use those resources.

Consistent with previous research (Reinke et al., 2011; Westling, 2010), the majority of participants reported that students in their classrooms exhibit challenging or disruptive behaviors. Eighty percent of participants reported feeling prepared to deal with challenging student behaviors, which is inconsistent with previous findings (e.g., Gable et al., 2012). This may be related to the teaching experience (M = 14 years) and education level (57% held master’s degrees with additional professional hours) of our sample. Despite the majority of participants feeling prepared to deal with challenging behaviors, 80% of participants indicated that they wanted more access to high-quality behavior-management practices. This suggests that even highly trained and experienced educators want additional resources to help effectively manage challenging student behavior.

Participants’ most frequent response was colleagues when asked where they first go for behavior-management resources. This sentiment is echoed in participants’ use ratings for colleagues, which were significantly higher than all other resources and affirmed by all focus-group participants. Information from colleagues also received the highest ratings regarding accessibility, implementability, understandability, and trust. These findings are consistent with previous studies (e.g., Landrum et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2010), which reported that teachers prefer to use information from colleagues because it is perceived as trustworthy, accessible, and usable. This notion is supported by both the quantitative and qualitative results from this study.

The reasons participants gave in the focus-group interviews for prioritizing colleagues as their preferred resource for classroom and behavior management challenges varied. Some participants went to colleagues because they were available to answer questions and help make adjustments to the recommended practice as needed. In addition, the majority of participants liked colleagues because they are familiar with their student(s) and classrooms and provide practices that teachers trust to be effective. As one participant stated, teachers do not want to “reinvent the wheel,” and going to colleagues provides battle-tested advice.

Whereas colleagues being the top choice was not surprising, we were surprised that internet media (i.e., YouTube, Pinterest, and Teachers Pay Teachers) received the lowest ratings of all resources. Previous studies (Hott et al., 2018; Opfer et al., 2016) reported that teachers frequently use Pinterest and Teachers Pay Teachers. It is possible that the highly educated, experienced, and confident nature of our sample influenced their low ratings of internet media. Although the quantitative evidence suggests that teachers do not use internet media, the qualitative results suggest that at least some educators frequently use Teachers Pay Teachers. All focus group participants mentioned purchasing items from Teachers Pay Teachers. One participant said, “Teachers definitely use Teachers Pay Teachers and Pinterest,” and another noted, “I spend my money on Teachers Pay Teachers.” However, one participant mentioned that Teachers Pay Teachers has relatively few resources for behavior management, so that may help to explain the low ratings of use of these resources.

Another interesting result is, despite the relatively low ratings for internet resources, approximately 90% of participants indicated that they downloaded materials from the internet, and almost 60% spent money to access these materials. Although many educators may not have agreed that they regularly used internet media as a resource for classroom and behavior management, almost all used internet media as an instructional resource, and most spent money to access resources on these websites. The average respondent reported spending $150 on downloaded materials, and five educators reported spending over $500, with one educator reporting to have spent “at least $1,000.” Focus-group participants also indicated that teachers spend money on resources from Teachers Pay Teachers. These findings indicate that despite their relatively low ratings of trust for internet resources, many teachers still choose to spend money to download these resources. Additional research is needed to further examine this issue.

Implications and Recommendations for Practice

Study findings indicate that teachers prefer to use colleagues as a behavior-management resource because they are easy to access and understand, and they provide trustworthy and usable information. Thus, researchers should strive to imbue research-based behavioral resources with these same beneficial characteristics. To illustrate, researchers may want to (1) avoid technical terms in articles and other research-based resources and (2) provide step-by-step guides on implementing recommended practices. Although providing sound evidence to support the effectiveness of recommended behavior practices is important, supplementing that evidence with resources that are usable and easily understood may facilitate educators’ understanding and adoption of the practices. Qualitative data suggested that teachers prefer their colleagues because colleagues recommend practices that seem to have been effective in their classroom. As such, researchers may want to include practice-based evidence when discussing research-based information (see Beahm & Cook, 2021). Practice-based evidence is generated in real classrooms by real teachers. For example, researchers may want to include a description of how a teacher implemented a strategy in their classroom and any adaptations they made. In addition, researchers might disseminate information using video models that include examples of application in real classroom settings.

As participants reported using colleagues more frequently than other resources, other resources targeting practitioners (e.g., PD, professional websites, practitioner-focused journals) may want to feature examples or stories from real-world educators when providing information on effective behavior-management practices. Some possible examples include using videos of a teacher implementing a targeted behavior-management practice and testimonials from educators describing their experiences with a practice on a website and in PD training. As focus group participants stated the need to see the practice in action, it may be beneficial for teachers to role-play implementing the practice. Another possibility would be to provide teachers with video models that they can access after receiving PD training.

In addition, as teachers indicated the need for information that was “quick and to the point,” PD providers might consider explicitly highlighting and rehearsing the critical elements involved in implementing targeted behavior-management practices during PD sessions. It may also be helpful to provide more information regarding the effectiveness of targeted strategies for different students (e.g., age range, disability status), for different outcomes (e.g., increasing engagement, reducing maladaptive behavior), and in different environments (e.g., whole class, small group, 1:1) to make easier for teachers to select an appropriate EBP for their students.

Implications and Recommendations for Future Research

This study provides preliminary insights into where educators go for behavior-management resources; their perceived use, trust in, accessibility to, implementability, and understanding of a variety of behavior-management resources; and preferred features of behavior-management resources. Future research should extend these initial findings by examining whether results vary by geographical region and across different professional roles (e.g., are there differences in how general and special educators perceive and use behavior-management resources?). We recommend that researchers continue to examine the features of behavior-management resources that teachers perceive as helpful and undesirable to inform and improve the design of behavior-management resources. As this research base matures, researchers can experimentally test the effects of various features of behavior-management resources on educators’ perceptions and of those resources and the implementation of targeted practices.

Limitations

One important limitation to the study is that both the survey and focus-group interviews relied on self-reported data, which are subject to response bias and may be influenced by social acceptability (Dillman et al., 2014). Although we attempted to minimize the possibility of response bias by informing participants that their responses were completely anonymous in the survey and confidential in the focus group, this limitation still exists. In addition, our response rate was only 12.4% on the survey. Although other studies involving web-based surveys of educators had similarly low response rates (e.g., Graziano & Bryans-Bongey, 2018; Webster et al., 2020) and Manfreda et al. (2008) found that low response rates are common in web-based surveys, it is important to consider that nonresponding educators may have responded differently. In addition, respondents tended to be highly confident, experienced, educated, white, and female; and were all from one region in a single state. It is possible that a more representative sample of educators may have responded differently to the survey items and in the focus groups.

Conclusion

Challenging student behavior occurs in most classrooms and, although most educators in our sample felt prepared to deal with behavioral challenges, they still expressed a need for more access to behavioral resources. Similar to previous findings (e.g., Boardman et al., 2005), our results suggest that educators primarily go to colleagues when faced with behavioral challenges because colleagues are easy to understand and provide usable information. Inconsistent with previous findings, professional and academic journals were rated as being used regularly by many educators, and internet media (i.e., YouTube, Pinterest, and Teachers Pay Teachers) were used relatively infrequently as resources for behavior-management strategies. Consistent with Carnine’s (1997) theory, our results suggest that educators’ use of resources aligns with perceived accessibility, usability, and trustworthiness. More research is necessary to understand what makes educators perceive resources as trustworthy, understandable, accessible, and usable; and how to manipulate these variables to influence educators’ use of behavior-management resources.

References

Beahm, L. A., & Cook, B. G. (2021). Merging practice-based evidence and evidence-based practices to lessen the research-to-practice gap. In B. G. Cook, M. Tankersley, & T. J. Landrum (Eds.), Advances in learning and behavioral disabilities: The next big thing (Vol. 32). Emerald.

Boardman, A. G., Argüelles, M. E., Vaughn, S., Hughes, M. T., & Klingner, J. (2005). Special education teachers’ views of research-based practices. Journal of Special Education, 39(3), 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224669050390030401.

Bradley, R., Doolittle, J., & Bartolotta, R. (2008). Building on the data and adding to the discussion: The experiences and outcomes of students with emotional disturbance. Journal of Behavioral Education, 17(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-007-9058-6.

Brunsting, N. C., Sreckovic, M. A., & Lane, K. L. (2014). Special education teacher burnout: A synthesis of research from 1979 to 2013. Education & Treatment of Children, 37(4), 681–711. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2014.0032.

Burns, M. K., & Ysseldyke, J. E. (2009). Reported prevalence of evidence-based instructional practices in special education. Journal of Special Education, 43(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466908315563.

Carnine, D. (1997). Bridging the research-to-practice gap. Exceptional Children, 63(4), 513–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440299706300406.

Cook, B. G., Cook, S. C., & Collins, L. W. (2016). Terminology and evidence-based practice for students with emotional and behavioral disorders: Exploring some devilish details. Beyond Behavior, 25(2), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/107429561602500202.

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. John Wiley & Sons.

Freeman, J., Simonsen, B., Briere, D. E., & MacSuga-Gage, A. S. (2014). Pre-service teacher training in classroom management: A review of state accreditation policy and teacher preparation programs. Teacher Education & Special Education, 37(2), 106–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406413507002.

Gable, R. A., Tonelson, S. W., Sheth, M., Wilson, C., & Park, K. L. (2012). Importance, usage, and preparedness to implement evidence-based practices for students with emotional disabilities: A comparison of knowledge and skills of special education and general education teachers. Education & Treatment of Children, 35(4), 499–519. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2012.0030.

Gage, N. A., & MacSuga-Gage, A. S. (2017). Salient classroom management skills: Finding the most effective skills to increase student engagement and decrease disruptions. Report on Emotional & Behavioral Disorders in Youth, 17(1), 13–18.

Gage, N. A., Adamson, R., MacSuga-Gage, A. S., & Lewis, T. J. (2017). The relation between the academic achievement of students with emotional and behavioral disorders and teacher characteristics. Behavioral Disorders, 43(1), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0198742917713211.

Garwood, J. D., Werts, M. G., Varghese, C., & Gosey, L. (2018). Mixed-Methods Analysis of Rural Special Educators’ Role Stressors, Behavior Management, and Burnout. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 37(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756870517745270.

Graziano, K. J., & Bryans-Bongey, S. (2018). Surveying the national landscape of online teacher training in K–12 teacher preparation programs. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 34(4), 259–277.

Hirn, R. G., & Scott, T. M. (2014). Descriptive analysis of teacher instructional practices and student engagement among adolescents with and without challenging behavior. Education & Treatment of Children, 37(4), 589–610. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2014.0037.

Hott, B. L., Dibbs, R.-A., Naizer, G., Raymond, L., Reid, C. C., & Martin, A. (2018). Practitioner Perceptions of Algebra Strategy and Intervention Use to Support Students With Mathematics Difficulty or Disability in Rural Texas. SAGE Journals. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756870518795494

Hudson, R. F., Davis, C. A., Blum, G., Greenway, R., Hackett, J., Kidwell, J., Liberty, L., McCollow, M., Patish, Y., Pierce, J., Schulze, M., Smith, M. M., & Peck, C. A. (2016). A socio-cultural analysis of practitioner perspectives on implementation of evidence-based practice in special education. Journal of Special Education, 50(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466915613592.

Kitzinger, J. (1995). Qualitative research: Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal, 311(7000), 299–302. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299.

Krueger, R. A. (2014). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Sage publications.

Landrum, T. J., Cook, B. G., Tankersley, M., & Fitzgerald, S. (2007). Teacher perceptions of the useability of intervention information from personal versus data-based sources. Education and Treatment of Children, 30(4), 27–42.

Manfreda, K. L., Bosnjak, M., Berzelak, J., Haas, I., & Vehovar, V. (2008). Web surveys versus other survey modes: A meta-analysis comparing response rates. International Journal of Market Research, 50(1), 79–104.

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass.

Morgan, D. L., & Spanish, M. T. (1984). Focus groups: A new tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Sociology, 7(3), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00987314.

Mostert, M. P. (2010). Asserting the fanciful over the empirical: Introduction to the special issue. Exceptionality, 18(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/09362830903462409.

Noltemeyer, A. L., Ward, R. M., & Mcloughlin, C. (2015). Relationship between school suspension and student outcomes: A meta-analysis. School Psychology Review, 44(2), 224–240. https://doi.org/10.17105/spr-14-0008.1.

Opfer, V. D., Kaufman, J. H., & Thompson, L. E. (2016). Implementation of K–12 state standards for mathematics and English language arts and literacy. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Rabiee, F. (2004). Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proceedings of the nutrition society, 63(4), 655–660.

Rausch, M. K., & Skiba, R. (2004). Disproportionality in school discipline among minority students in Indiana: Description and analysis. Children left behind policy briefs. Supplementary analysis 2-A. Center for Evaluation and Education Policy, Indiana University.

Reinke, W. M., Stormont, M., Herman, K. C., Puri, R., & Goel, N. (2011). Supporting children’s mental health in schools: Teacher perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. School Psychology Quarterly, 26(1), 1.

Scott, T. M. (2017). Training classroom management with preservice special education teachers: Special education challenges in a general education world. Teacher Education & Special Education, 40(2), 97–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406417699051.

Simonsen, B., Fairbanks, S., Briesch, A., Myers, D., & Sugai, G. (2008). Evidence-based practices in classroom management: Considerations for research to practice. Education & Treatment of Children, 31(3), 351–380. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.0.0007.

Smith, G. J., Richards-Tutor, C., & Cook, B. G. (2010). Using teacher narratives in the dissemination of research-based practices. Intervention in School and Clinic, 46(2), 67–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451210375301.

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748.

Vanderlinde, R., & van Braak, J. (2010). The gap between educational research and practice: Views of teachers, school leaders, intermediaries and researchers. British Educational Research Journal, 36(2), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920902919257.

Webster, C. A., Mîndrilă, D., Moore, C., Stewart, G., Orendorff, K., & Taunton, S. (2020). Measuring and comparing physical education teachers’ perceived attributes of CSPAPs: An innovation adoption perspective. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 39(1), 78–90.

Westling, D. L. (2010). Teachers and challenging behavior: Knowledge, views, and practices. Remedial and Special Education, 31(1), 48–63.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Research approved by UVA IRB – SBS #303

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beahm, .A., Yan, X. & Cook, B.G. Where Do Teachers Go for Behavior Management Strategies?. Educ. Treat. Child. 44, 201–213 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43494-021-00046-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43494-021-00046-2