Abstract

Morally speaking, what should one do when one is morally uncertain? Call this the Moral Uncertainty Question. In this paper, I argue that a non-ideal moral theory provides the best answer to the Moral Uncertainty Question. I begin by arguing for a strong ought-implies-can principle—morally ought implies agentially can—and use that principle to clarify the structure of a compelling non-ideal moral theory. I then describe the ways in which one’s moral uncertainty affects one’s moral prescriptions: moral uncertainty constrains the set of moral prescriptions one is subject to, and at the same time generates new non-ideal moral reasons for action. I end by surveying the problems that plague alternative answers to the Moral Uncertainty Question, and show that my preferred answer avoids most of those problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We can’t answer this question by appealing to claims about rational norms, because it’s conceivable that rational norms diverge from moral norms.

Note that I’m focusing on “pure” or “morally-based” moral uncertainty, that is, on moral uncertainty that isn’t traceable to non-moral uncertainty. Although the focus of this paper is on pure moral uncertainty, we can extend the view developed in this paper to instances of impure moral uncertainty, as well as to other types of uncertainty and ignorance.

In other words, a moral theory is “non-ideal” when its action-prescriptions are sensitive to the flaws—including moral flaws—of agents. Many non-ideal moral theories focus on the ways in which oppression morally compromises agents who are members of oppressed groups; the non-ideal theory I favor is also sensitive to agential imperfections that aren’t immediately traceable to the experience of oppression. See Mills (2005), Rivera-López (2013), and Tessman (2010).

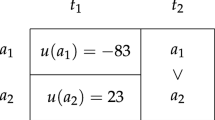

Not all deontic verdicts express prescriptions; for example, when a moral theory delivers the deontic verdict that \(\phi\)-ing is forbidden, we shouldn’t say that the theory “prescribes” \(\phi\)-ing. A paradigm case of a moral theory prescribing an action is a moral theory that delivers the deontic verdict that \(\phi\)-ing is obligatory. A moral theory can also be said to prescribe \(\phi\)-ing when it delivers the deontic verdict that \(\phi\)-ing is permissible, and no other action in the context is obligatory or permissible. As I will clarify in Sect. 1.2, on my view, it is possible for an agent to have only one permissible action available to them, and yet at the same time not be obligated to perform that action.

For example, philosophers disagree about whether “supererogatory” is a genuine deontic status. For an excellent overview of the main debates about supererogation, see Muñoz (forthcoming).

Portmore makes a similar observation when he writes, “Now, it would be very strange to think that morality could require me to respond inappropriately to my reasons given that what makes me the sort of subject to whom moral obligations and responsibilities apply is that I’m the sort of subject who’s capable of responding appropriately to my reasons—that is, a rational agent. And it seems nonsensical for some moral requirement to apply to me because I have the capacity to respond appropriately to my reasons if I can fulfill that requirement only by failing to respond appropriately to my reasons.” See Portmore (2019, pp. 177-178).

If a third party is deliberating about what someone else ought to do, it’s pointless for the third party to consider agency-compromising events that one could undergo. The consideration of agency-compromising events wouldn’t help the third party see what one ought to do, because an agency-compromising event is something that an agent can’t produce through a full-fledged exercise of their agency.

Notice that agential possibility is distinct from other types of possibility. First, it’s distinct from physical possibility. There are some physically possible actions that are not agentially possible, because they rely on intervening events. There could also be physically impossible actions that are agentially possible; this could happen if there are physically impossible worlds in which the agent continues to respond to reasons in a way that is characteristic for the agent. (Thus, even if physical determinism is true, an agent could still have multiple agentially possible courses of action.) Second, agential possibility is distinct from psychological possibility (although I suspect that the two are related). For example, an action could be psychologically possible for me, and yet might require that I not respond to normative reasons at all; that action would be psychologically possible but agentially impossible.

I contrast normative reasons with motivating reasons. I treat normative reasons as a broad category; they include both moral reasons and reasons of rationality.

Note that a normative reason need not be a decisive reason; it can be “outweighed” by other reasons. Although I sometimes use the language of “weighing” reasons, I don’t intend for the reader to take the weight metaphor too seriously.

“Things” here can include objects, states of affairs, actions, or persons; I want to remain neutral on what, exactly, the bearers of value are.

Thus, it’s plausible that in order to perfectly successfully respond to a reason, one must also respond well to other reasons in one’s context; responding well to all reasons in a context is the only way to properly judge any particular reason’s relative strength.

An agent has a “de re” (vs. “de dicto”) desire for x when it’s true of x that the agent desires it, even if the agent does not desire it under the description “x.” (If an agent desires x under the description “x,” then the agent desires x “de dicto”.) An agent who has the capacity to respond to normative reasons must have some de re desires for things of genuine value, because a person who lacks de re desires for anything of genuine value does not have the ability to be motivated by any normative reasons, and thus lacks the capacity to respond to normative reasons. One might still have the capacity to develop de re desires for things of genuine value, in which case we can say that the person has the potential for agency.

There might be features other than an agent’s limitations (such as personality quirks) that determine the way in which the agent is disposed to respond to normative reasons; even so, an agent’s limitations play a significant role in determining the character of one’s agency.

The “character of one’s agency” must be distinguished from one’s “character,” in the virtue-theoretic sense. We can speak of the character of one’s agency—the specific way in which one is disposed to respond to normative reasons—at a particular time, whereas one’s character (in the virtue-theoretic sense) is determined by one’s long-standing dispositions.

This is a variation of a case made famous in Jackson (1991).

I have added some new details about the physician’s psychological dispositions. This is because, according to the view I’m arguing for, whether an action is “agentially possible” for an agent depends on the specific details of that agent’s psychology—details that are not normally mentioned in standard presentations of this example.

At this point, the reader might wonder whether I’m endorsing Williams’ reasons-internalism, according to which (roughly) S has a reason to \(\phi\) if and only if (1) S has a subjective motivational set some element of which motivates S to \(\phi\) or (2) there is a sound deliberative route by which S could come to have such a subjective motivational set (Williams 1981). However, my view is not the same as Williams’. First, note that Williams’ view concerns practical reasons in general, whereas I focus on moral prescriptions in particular. Second, note that Williams’ view is a view about reasons and not about prescriptions or oughts. Third, my rough account of the origin of normative reasons is arguably in tension with reasons-internalism.

The objector might think that such a disposition is constitutive of agency.

It need not be the promotion relation; but the promotion relation gives us a simple way of seeing how such a ranking can be generated. Note that the ranking assumption, combined with the assumption that the relevant relation between actions and moral values is the promotion relation, amounts to the assumption that an adequate moral theory has a teleological structure. See Dietrich and List (2017).

Although agentially impossible actions might be able to receive other sorts of deontic verdicts. For example, even if it’s agentially impossible for me to kill my beloved cat, perhaps an adequate moral theory can still deliver the deontic verdict that killing my cat is wrong (or that killing my cat would be wrong). All I claim here is that agentially impossible actions cannot be prescribed—they cannot be what one morally ought to do.

If some agentially possible actions are physically impossible, we will need to introduce additional ought-implies-can principles—such as ought implies physically can—that place further contraints on which actions the theory can prescribe. The introduction of additional ought-implies-can principles is consistent with the thesis of this paper.

See Sect. 3 for a more detailed explanation of why I treat this non-ideal theory as an “objectivist” theory.

My account can be extended to other, more complicated forms of empirical uncertainty, such as miners puzzles (Regan 1980). What one morally ought to do, if one is in a miners puzzle, is the most value-promoting agentially possible action. Which action that is depends on (a) what the correct axiological theory says about how much moral value is promoted by each item on one’s menu of options and (b) the character of one’s agency.

Of course, if Ayo only has two options—(a) and (b)—then both options could be agentially possible for Ayo; this is because which options are agentially possible for an agent depends on the entire menu of options from which an agent chooses. For example, if I’m choosing between eating a cookie and sawing off my foot, sawing off my foot will be agentially impossible for me; but if I’m choosing between dying while trapped under a boulder and sawing off my foot, sawing off my foot could become agentially possible for me. Similarly, if Ayo has no one to turn to for consultation (and so (c) is no longer on Ayo’s menu of options), Ayo might be agentially able to choose (a) or (b).

I borrow the terms “transitional” and “non-transitional” from Berg (2018).

Hicks (2019).

The fact that my answer satisfies the second desideratum, while “half-satisfying” the first, allows me to avoid most of the critiques of non-ideal moral theory in Tessman (2010).

I develop this point in detail in Hicks (forthcoming).

Graham (2010).

Similarly, such objectivist views will also violate OIAC is cases of moral uncertainty. For example, Graham’s view entails that it’s not the case that Ayo, in the Triage example from Sect. 2.1, should pursue option (c).

Note that proponents of these non-ideal moral theories take their theories to be objective and mental state-sensitive, like my own.

Lawford-Smith (2013, pp. 655–658).

Lawford-Smith (2013, 662).

Lawford-Smith (2013, p. 662). Lawford-Smith says that even when an agent “has no reason” to act in a particular way, that action is still within the agent’s option set.

Berg (2018).

Berg (2018, p. 19).

Muñoz and Spencer make a similar point in section 4 of “Knowledge of Objective ‘Oughts’: Monotonicity and the New Miners Puzzle” (forthcoming).

Rosenthal (2019, p. 10).

See Rosenthal (2019, p. 14), for a discussion of how procedural oughts can be determined by more objective or more subjective factors.

Zimmerman (2014).

Whether one can have a rational credence in a horrifying moral proposition is controversial; however, rational credences in horrifying moral propositions seems to be possible, on Zimmerman’s view. Gideon Rosen highlights this potential weakness in a review of Zimmerman’s Ignorance and Obligation. Rosen writes, “Consider the Nazi doctor who experiments on prisoners in the honest belief that the misery he causes counts for nothing. The only sane thing to say about such cases is that whatever the Nazi may think, people have a right not to be treated in these ways simply in virtue of being persons, and that it is one of the great discoveries in moral history that people have always had this right. The ‘total evidence’ version of the Prospective View can say this, provided we think that universally available evidence justifies the belief that human suffering always matters morally. Zimmerman’s more subjectivist view must say instead that such rights only exist when the bearers of the corresponding duties appreciate the values that underlie them.” See Rosen (2015).

This claim is partly supported by the intuitive assumption I flagged in Sect. 1.1, that an agent usually has multiple agentially possible actions.

Recall from footnote 13 that when someone has a de dicto desire for x, they desire x under the description “x.” Someone who has de dicto concern for morality desires to do the right thing as such.

This is an extremely implausible assumption; I make it only for the purposes of illustration.

Hicks (2019).

See footnote 13.

But not always; there are some cases in which the agent has no time to reflect.

References

Berg, A. (2018). Ideal theory and ought implies can. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 99(4), 869–890. https://doi.org/10.1111/papq.12228.

Dietrich, F., & List, C. (2017). What matters and how it matters: A choice-theoretic representation of moral theories. The Philosophical Review, 126(4), 421–479. https://doi.org/10.1215/00318108-4173412.

Graham, P. (2010). In defense of objectivism about moral obligation. Ethics, 121(1), 88–115. https://doi.org/10.1086/656328

Harman, E. (2015). The Irrelevance of Moral Uncertainty. In Russ Shafer-Landau (Ed.), Oxford studies in Metaethics (Vol. 10). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198738695.003.0003

Hicks, A. (2019). Moral hedging and responding to reasons. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 100(3), 765–789. https://doi.org/10.1111/papq.12274.

Hicks, A. (forthcoming). Dispensing with the subjective moral ‘Ought.' In M. Timmons (Ed.), Oxford studies in normative ethics (Vol. 11). Oxford University Press.

Jackson, F. (1991). Decision-theoretic consequentialism and the nearest and dearest objection. Ethics, 101(3), 461–482. https://doi.org/10.1086/293312.

Lawford-Smith, H. (2013). Non-ideal accessibility. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 16(3), 653–669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-012-9384-1.

List, C. (2019). Why free will is real. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674239807.

Lockhart, T. (2000). Moral uncertainty and its consequences. Oxford University Press.

MacAskill, W. (2014). Normative uncertainty, Dissertation. University of Oxford.

Mills, C. (2005). Ideal theory as ideology. Hypatia, 21(3), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2005.tb00493.x.

Muñoz, D. (forthcoming). Three paradoxes of supererogation. Nous. https://doi.org/10.1111/nous.12326.

Muñoz, D., & Spencer, Jack. (forthcoming). Knowledge of objective ‘Oughts’: Monotonicity and the new miners puzzle. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpr.12702.

Nefsky, J. (2017). How you can help, without making a difference. Philosophical Studies, 174(11), 2743–2767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-016-0808-y.

Portmore, D. (2019). Opting for the Best: Oughts and Options. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190945350.001.0001.

Prichard, H. A. (1968). Duty and Ignorance of Fact. Moral Obligation (and) Duty and Interest: Essays and Lectures (pp. 18–39). Oxford University Press.

Regan, D. (1980). Utilitarianism and cooperation. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198246091.001.0001.

Rivera-López, E. (2013). Ideal and Nonideal Ethics and Political Philosophy. In Hugh LaFollette (Ed.), International encyclopedia of ethics. Blackwell.

Rosen, G. (March 2015). Review of Ignorance and Obligation by Michael Zimmerman. Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews. https://ndpr.nd.edu/news/ignorance-and-moral-obligation/.

Rosenthal, C. (2019). Ethics for fallible people, Dissertation. New York: New York University.

Sepielli, A. (2009). What to do when you dont know what to do. In Russ Shafer-Landau (Ed.), Oxford studies in Metaethics (Vol. 4). Oxford University Press.

Smith, H. M. (2018). Making morality work. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199560080.001.0001.

Tarsney, C. (2018). Intertheoretic value comparison: A modest proposal. Journal of Moral Philosophy, 15(3), 324–344. https://doi.org/10.1163/17455243-20170013.

Tessman, L. (2010). Idealizing morality. Hypatia, 25(4), 797–824. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2010.01125.x.

Weatherson, B. (2014). Running risks morally. Philosophical Studies, 167(1), 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-013-0227-2.

Williams, B. (1981). Internal and External Reasons. Moral Luck. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139165860.009.

Zimmerman, M. (2014). Ignorance and moral obligation. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199688852.001.0001.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank the participants at the 3rd Annual Chapel Hill Normativity Workshop for their feedback on this paper, especially Christa Johnson for her excellent comments. I′m very grateful to Chris Howard and Alex Worsnip for organizing such a fantastic workshop. I’d also like to thank the participants in the 2019 Ohio State University/Maribor/Rijeka Philosophy Conference in Moral Epistemology for helpful discussion of the main ideas in this paper; I’m particularly grateful to David Faraci and Tristram McPherson for their feedback on this project. And finally, I’d like to thank my colleagues in the Philosophy Department at Kansas State University for their feedback on an early draft of this paper, especially Shanna Slank, Reuben Stern, Graham Leach-Krouse, Scott Tanona, Jim Hamilton, and Bruce Glymour.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hicks, A. Non-ideal prescriptions for the morally uncertain. Philos Stud 179, 1039–1064 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-021-01686-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-021-01686-1