Abstract

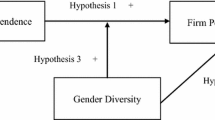

This research paper aims to examine the association between product market competition and gender diversity on the corporate board. More specifically, this paper examines the likely corporate governance determinants of firms operating by female directors. This study included all the Australian listed companies in the primary list of samples from 2001 to 2015. This research explored that low competition increases the probability of existing female directors on the corporate board. Results also reveal that low product market competition is positively associated with firms’ female directors where female directors are the member of the audit committee and have long service experience. This research obtains evidence that low-competitive firms encourage board gender diversity even if their presence is insignificant (as a token). This study contributes to the literature by providing evidence that first, low competition drives managers to appoint female directors on board as few primarily large firms with low competition show fairness to comply with corporate governance regulations, especially on gender diversity. Moreover, low competition forces firms to search for unique competitive advantage, and gender diversity is one of them which can increase the visibility of female directors. Finally, a firm’s board gender diversity can ensure intense monitoring, rational decision, advising, calculative risk-taking comparing with a gender bias board and leading to a good firm image for the stakeholders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Women directors can provide intense monitoring, valuable, practical input, because they may have a deeper understanding of what drives consumers since they make the purchasing decisions for their families (Stoiljkovic, 2011).

In a large firm, managers may take more risks by investing their high profit in research and development activities. However, sometimes, large firms are found less inventive to innovate and invest in the absence of competitive pressures. They may not try very hard to improve themselves. Therefore, workers and managers may simply lack the necessary motivation to work hard, which encouraging x-inefficiency (organizational slack). This kind of situation may arise principal-agent problem.

The opposite scenario may exist like, competition can produce better managerial incentives as in a highly competitive market, the space of profit may be compressed or plundered by others, and only efficient firms can survive. Therefore, to avoid aggregate shocks by competitors, bankruptcy, and to ensure efficiency firms used to provide incentives to managers, which ultimately reduces free cash flows and improves monitoring quality. Thus, managers in a highly competitive industry are more vigilant as they have the fear of the loss of their jobs, so managers distribute excess cash to shareholders as dividends to avoid agency problems between the shareholders and the manager. Therefore, this may increase the managerial reputation and suppress the urge for diverse monitoring by increasing the corporate board's female directors’ ratio.

References

Abbott, L. J., Parker, S., & Presley, T. J. (2012). Female board presence and the likelihood of financial restatement. Accounting Horizons, 26(4), 607–629. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-50249

Adams, R. B., Gray, S., & Nowland, J. (2010). Is there a business case for female directors? Evidence from the market reaction to all new director appointments. In 23rd Australasian Finance and Banking Conference.

Adams, R. B., & Ferreira, D. (2009). Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 94(2), 291–309.

Aghion, B. P., Reenen, J. V., & Zingales, L. (2013). Innovation and institutional ownership. American Economic Review, 103(1), 277–304.

Ahern, K. R., & Dittmar, A. K. (2012). The changing of the boards: The impact on firm valuation of mandated female board representation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(1), 137–197.

Ahmed, A., Higgs, H., Ng, C., & Delaney, D. A. (2018). Determinants of women representation on corporate boards : Evidence from Australia. Accounting Research Journal, 31(3), 326–342. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-11-2015-0133

Alsaeed, K. (2005). The association between firm-specific characteristics and disclosure: The case of Saudi Arabia. Managerial Auditing Journal, 21(5), 476–496. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900610667256

Arnegger, M., Hofmann, C., Pull, K., & Vetter, K. (2014). Firm size and board diversity. Journal of Management & Governance, 18, 1109–1135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-013-9273-6

Baggs, J., & de Bettignies, J.-E. (2005). Product market competition and agency costs. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 55(2), 289–323.

Becker, G. S. (1957). The economics of discrimination. University of Chicago Press.

Beiner, S., Schmid, M., & Wanzenried, G. (2011). Product market competition, managerial incentives and firm valuation. European Financial Management, 17(2), 331–366.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Pavelin, S. (2009). Corporate reputation and women on the board. British Journal of Management, 20, 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00600.x

Carter, D. A., Simkins, B. J., & Simpson, W. G. (2003). Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. The Financial Review, 38(1), 33–53.

Chen, J., Leung, W. S., & Evans, K. P. (2018). Female board representation, corporate innovation and firm performance. Journal of Empirical Finance, 48(July), 236–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2018.07.003

Chou, J., Ng, L., Sibilkov, V., & Wang, Q. (2011). Product market competition and corporate governance. Review of Development Finance, 1(2), 114–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdf.2011.03.005

Collin, S., & Bengtsson, L. (2000). Corporate Governance and strategy : A test of the association between governance structures and diversification on Swedish data. Corporate Governance, 8(2), 154–165.

Cox, T. H., & Blake, S. (2013). Managing cultural implications for competitiveness organizational. Academy of Management Executive, 5(3), 45–56.

Davidson, W. N., & Rowe, W. (2004). Intertemporal Endogeneity in Board composition and Financial Performance. Corporate Ownership & Control, 1(4), 49–60.

de Cabo, R. M., Gimeno, R., & Nieto, M. J. (2012). Gender diversity on European banks ’ boards of directors. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(2), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/sl0551-011-1112-6

Dickinson, V. (2011). Cash flow patterns as a proxy for firm life cycle. The Accounting Review, 86(6), 1969–1994. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-10130

Eastman, M. T. (2017). Women on Boards: Progress Report 2017. MSCI, December 2017.

Farrell, K. A., & Hersch, P. L. (2005). Additions to corporate boards: The effect of gender. Journal of Corporate Finance, 11(1–2), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2003.12.001

García-Meca, E., & Palacio, C. J. (2018). Board composition and firm reputation: The role of business experts, support specialists and community influentials. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 21(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2018.01.003

Ghosal, V. (2002). Potential foreign competition in US manufacturing. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 20(10), 1461–1489.

Giroud, X., & Mueller, H. M. (2009). Does Corporate Governance Matter in Competitive Industries?

Gujarati, D. N. (2003). Basic Econometrics. McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Gujarati, D., & Porter, D. (2009). Basic Econometrics (5th ed.). Mc Graw-Hill.

Gul, F. A., Fung, S. Y. K., & Jaggi, B. (2009). Earnings quality : some evidence on the role of auditor tenure and auditors ’ industry expertise. Journal of Accounting and Economics, (March).

Gul, F. A., Srinidhi, B., & Ng, A. C. (2011). Does board gender diversity improve the informativeness of stock prices? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 51(3), 314–338.

Habib, A., Bhuiyan, B. U., & Hasan, M. M. (2017). Firm life cycle and advisory directors. Australian Journal of Management, 00, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896217731502

Habib, A., Bhuiyan, M. B. U., & Sun, X. S. (2019). Audit partner busyness and cost of equity capital, (September 2018), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12144

Hair, J. J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (3rd ed.). Macmillan.

Hart, O. D. (1983). The market mechanism as an incentive scheme. The Bell Journal of Economics, 14(2), 366–382.

Herring, C. (2009). Does diversity pay?: Race, gender, and the business case for diversity. American Sociological Review, 34(2), 208–224.

Hill, C. W. L., & Hansen, G. S. (1991). A longitudinal study of the cause and consequences of changes in diversification in the U.S. Strategic Management Journal, 12(3), 187–199.

Hillman, A. J., & Dalziel, T. (2003). Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. The Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 383–396.

Hillman, A. M. Y. J., Shropshire, C., & Cannella, A. A. (2007). Organizational predictors of women on corporate boards. Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 941–952.

Huse, M., & Solberg, A. G. (2005). Gender-related boardroom dynamics: How Scandinavian women make and can make contributions on corporate boards. Women in Management Review, 21(2), 113–130.

Issa, A., Elfeky, M. I., & Ullah, I. (2019). The impact of board gender diversity on firm value: Evidence from Kuwait. International Journal of Applied Science and Research, 2(1), 1–22.

Kajola, S. O., Olabisi, J., Soyemi, K. A., & Olayiwola, P. O. (2019). Board gender diversity and dividend policy in Nigerian listed firms. ACTA VŠFS, 13(2), 135–151.

Kang, H., Cheng, M., & Gray, S. J. (2007a). Corporate governance and board composition : Diversity and independence of Australian boards. Journal of Corporate Governance : An International Review, 15(2), 194–207.

Kang, H., Cheng, M., & Gray, S. J. (2007b). Corporate governance and board composition : Diversity and independence of Australian boards. Journal of Corporate Governance : An International Review, 15(2), 194–207.

Karuna, C. (2007). Industry product market competition and managerial incentives. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 43(August), 275–297. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.775284

Kim, J. H., & Lee, W.-M. (2018). How does board structure affect customer concentration? SSRN Electronic Journal 1–43. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3238644

Laksmana, I., & Yang, Y. (2015). Product market competition and corporate investment decisions. Review of Accounting and Finance, 14(2), 128–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAF-11-2013-0123

Milliken, F. J., & Martins, L. L. (1996). Searching for common threads: Understanding the multiple effects of diversity in organizational groups. Academy of Management Review, 21(2), 402–433.

Mirza, S. S., Majeed, M. A., & Ahsan, T. (2020). Board gender diversity, competitive pressure and investment efficiency in Chinese private firms. Eurasian Business Review, 10, 417–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-019-00138-5

Nickell, S. J. (1996). Competition and corporate performance. Journal of Political Economy, 104(4), 724–746.

Pandey, R., Biswas, P. K., Ali, M. J., & Mansi, M. (2019). Female directors on the board and cost of debt: evidence from Australia. Accounting and Finance.https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12521

Peress, J. (2010). Product market competition, insider trading, and stock market efficiency. The Journal of Finance, 65(1), 1–43.

Post, C., & Byron, K. (2015). Women on boards and firm financial performance: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 58(5), 1546–1571.

Prevost, A. K., Rao, R. P., & Hossain, M. (2002). Board composition in New Zealand : An agency perspective. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 29(5–6), 731–760.

Pucheta-mart, C., Bel-Oms, I., & Olcina-Sempere, G. (2016). Corporate governance, female directors and quality of financial information. Business Ethics: A European Review, 1–23.https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12123

Quinones, M. A., Ford, J. K., & Teachout, M. S. (1995). The relationship between work experience and job performance: A conceptual and meta-analytic review. Personnel Psychology, 48(4), 887–910.

Rossi, F., Hu, C., & Foley, M. (2017). Women in the boardroom and corporate decisions of italian listed companies : Does the “ critical mass ” matter ? Management Decision, 55(7), 1578–1595.

Rumsey, D. (2007). Intermediate Statistics for Dummies. Wiley Publishing Inc.

Schmidt, K. M. (1997). Managerial incentives and product market competition. The Review of Economic Studies, 64(2), 91–213.

Searby, L., & Tripses, J. (2006). Breaking perceptions of "old boys’ networks": Women leaders learning to make the most of mentoring relationships. Journal of Women in Educational Leadership, 4(3), 29–46.

Shen, W. (2003). The dynamics of the Ceo-board relationship: An evolutionary perspective. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 466–476.

Shin, Y. Z., Chang, J., Jeon, K., & Kim, H. (2019). Female directors on the board and investment efficiency : evidence from Korea. Asian Business & Management, (April), 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-019-00066-2

Slade, M. (2004). Competing models of firm profitability. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 22, 289–308.

Srinidhi, B., Gul, F. A., & Tsui, J. (2011). Female directors and earnings quality. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28(5), 1610–1644. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2011.01071.x

Srinidhi, B., Zhang, H., & Chen, S. (2020). How do female directors improve board governance? A mechanism based on norm changes. Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, 16(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcae.2019.100181

Stoiljkovic, N. (2011). Women on boards: A conversation with male directors. In M.-L. Guy, C. Niethammer, & A. Moline (Eds.), Global Corporate Governance Forum (pp. 1–60). The International Finance Corporation.

Terjesen, S., Sealy, R., & Singh, V. (2009). Women directors on corporate boards : A review and research agenda. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(3), 320–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2009.00742.x

Terjesen, S., Couto, E. B., & Francisco, P. M. (2015). Does the presence of independent and female directors impact firm performance ? A multi-country study of board diversity. Journal of Management & Governance, 20(3), 447–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-014-9307-8

Wang, S. F., Jou, Y. J., Chang, K. C., & Wu, K. W. (2014). Industry competition, agency problem, and firm performance. Romanian Journal of Economic Forecasting, 17(4), 76–93.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2009). Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach (4th ed.). USA Cengage Learning.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the insightful input of two anonymous reviewers. The authors are thankful to Md Borhan Uddin Bhuiyan for his constructive suggestions on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A Variable definition

Appendix A Variable definition

Variables | Definition | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

Dependent variables | ||

FD | Female/woman directors | We have considered three different proxies of female/woman directorship (FD) |

%FD | % of female/woman representation | Total number of female/woman directors divided by total board size |

D_FD | Dummy variable of the female/woman director | Assigned a value equal to 1 if the firms have a female/woman director, otherwise 0 |

%INDFD | % of an independent female/woman director | Dividing the number of independent female/woman directors by total board size |

FD t-1 | Previous year percentage of female/woman directors on board | Lagged percentage of female/woman directors on board |

D_FD t-1 | Previous year female/woman director’s dummy | Lagged of female/woman directors’ dummy |

%INDFD t-1 | Previous year percentage of independent female/woman directors on board | Lagged percentage of independent female/woman directors on board |

FAC | Dummy variable of the Audit committee | Assigned a value 1 if the audit committee has 1 or more female/woman director, otherwise 0 |

FD TENURE | Dummy variable of female/woman directors' service tenure | Used as a proxy of female/woman experience. Assign value 1 if a female/woman director has more than 8 years of service tenure, otherwise 0 |

FD1 | Firms with only one female/woman director | Used as a proxy of tokenism. Assign value 1 if a firm has only one female/woman director, otherwise 0 |

FD2 | Firms with three or more female/woman directors | Assigned value 1 if a firm has two or more female/woman directors, otherwise 0 |

Independent variables | ||

HHI | Herfindahl–Hirschman Index. It is used as a proxy for product market competition (PMC) | It was calculated as the sum of the squared market share |

HHI1 t-1 | Previous year competition | Firm’s competition with a lag of one period |

CR4 | Four-firm concentration ratio also used as an alternative proxy of competition in the addition test section | Four-firm concentration ratio, calculated as the sum total market share of the four firms with the largest market share for each industry (classified by the two-digit GICS codes) and each year |

BODSIZE | Board size | Total number of directors in a board |

BODIND | Board independence | Measured by the proportion of independent directors on the total board |

CEODUAL | CEO duality | CEO was set equal to “1” if the role is held by the same individual and “0” otherwise |

CEOTENURE | CEO Tenure | Measured as the absolute number of years of CEO tenure |

OWNCON | Ownership concentration | Measured as the percentage shares owned by substantial shareholders |

ROA | Return on assets | It was measured by dividing net income by total assets |

LFSIZE | A natural log value of firm size | It was measured by total assets |

LEVERAGE | Firm’s leverage | This is the ratio of total debt to total assets |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salma, U., Qian, A. Determinants of firm’s holding female directors: evidence from Australia. Asian J Bus Ethics 10, 245–273 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-021-00129-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-021-00129-8