Abstract

Emergency frames are mobilized in contemporary sustainability debates, both in response to specific events and strategically. The strategic deployment of emergency frames by proponents of sustainability action aims to stimulate collective action on issues for which it is lacking. But this is contentious due to a range of possible effects. We critically review interdisciplinary social science literature to examine the political effects of emergency frames in sustainability and develop a typology of five key dimensions of variation. This pinpoints practical areas for evaluating the utility of emergency frames and builds a shared vocabulary for analysis and decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The notion of emergency has become prominent in contemporary sustainability science and politics. Sustainability issues, especially climate change and biodiversity loss, are increasingly declared as society-wide emergencies by scientists, civil society groups, cities, national governments and international organizations in an attempt to focus attention and accelerate action. Only five years after the first climate emergency declaration in 2016, almost 2,000 such declarations have been issued (https://climateemergencydeclaration.org). At the same time, acute and unprecedented climate change-related impacts (for example, wildfires, droughts, floods) are occurring with increasing frequency and magnitude, creating sharply felt emergencies in specific locations, and anxiety about the futures they portend. An emergency frame is a sense-making lens that conveys the meaning that a given set of circumstances constitutes an emergency. However, the consequences of using emergency frames in sustainability governance are complex, and, so far, not well understood. Moreover, the strategic deployment of emergency frames is contentious. While the urgency and irreversibility of unfolding global environmental changes are highlighted as justification, scholars disagree about the implications and merits of emergency frames for advancing collective action, and sometimes even strongly caution against it. Making sense of this contradictory picture requires a critical synthesis of the diverse possible effects of emergency frames to inform effective and politically astute responses.

The political effects of emergency frames may vary across different times, places and issue domains, and depending on who mobilizes this framing. For example, emergency frames may convey the urgency necessary to avoid further destruction of the environment and promote positive action1, thereby opening up new political possibilities for consensual sustainability action. But emergency frames may also polarize debates2, lead to public fatigue over time, trigger political defensiveness or even enable power grabs. Different scholarly disciplines and fields identify various fragmented aspects of this picture, creating ambiguity and conflicting claims about the normative merit of emergency frames and, worryingly, their actual empirical effects. Therefore, whether emergency frames are conducive or counterproductive to mobilizing sustainability action—and ultimately societal transformations—is not clear. Despite growing attention to the emergence of emergency frames, there is a lack of systematic understanding of their effects in sustainability governance, as well as their variation within and across contexts. Furthermore, experiences under the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic give new impetus for understanding the range of effects that might arise under emergency involving governmental, social and even military actions.

This Review synthesizes interdisciplinary insights concerning the political effects of emergency frames across diverse but fragmented disciplines. This material draws from: political science (22.1%), sustainability science (16.8%), policy studies (13.3%), sociology (12.4%), human geography (10.6%), social psychology (8.8%) and others (including law and human rights, science and technology studies, science communication; 15.9%) (Supplementary Note 1). The focus is on emergency frames in the field of environmental sustainability, but also draws on insights from other substantive fields (for example, disaster/crisis, social justice, security studies, COVID-19) where this is particularly relevant for understanding the political effects of emergency frames in sustainability. This enables an interdisciplinary review of the specific issue of emergency in sustainability to uncover diverse insights on this topic and provide a foundation for future work.

The methodology involved: (1) an exploratory dialogue with a global interdisciplinary group of approximately 50 social scientists at the 2020 Virtual Forum on Earth System Governance (16 September 2020) to inductively identify key themes; (2) structured literature searches to identify relevant issues and debates; and (3) interpretive review3 among the interdisciplinary author team to identify key effects and debates. The material reviewed was evenly split between speculative work (that is, primarily conceptual and/or opinion; 49.6%) and empirically informed work (that is, empirical using original data 28.7% or synthesis compiling existing data 21.7%; 50.4%) (Supplementary Note 1). Our findings result in a typology comprising five dimensions of variation in the political effects of emergency frames: (1) engagement among mass publics; (2) empowerment or disempowerment of social actors; (3) shifts in formal political authority; (4) reshaping of discourse; and (5) impacts on institutions. The overall implication is that sustainability scholars, policymakers and civil society should not be too quick to embrace nor discard the notion of emergency, as its utility may vary across contexts (for example, in interplay with existing debates, and depending on the presence of safeguards against adverse consequences) and over time (for example, short-term versus long-term role in stimulating and reinforcing societal transformations).

Emergency frames

This section first empirically profiles the attention on emergency in current sustainability debates, and then elaborates on the notion of an emergency frame and its attributes.

Emergency in contemporary sustainability

The use of emergency frames occurs in two distinct ways in contemporary sustainability science and politics. First, emergency frames are employed in response to acute issues. Examples include the ‘day zero’ water crisis in Cape Town in 20184, unprecedented wildfires in Australia in 2019–20205, major wildfires in the Amazon (2019–2020) and the western United States (2020), and recent climate change-related disasters in India in 2018–2019, including a ‘day zero’ water crisis in Chennai and devastating floods in Kerala. Second, emergency frames are now being deployed as a strategic tool to mobilize attention, resources and effort to address an issue for which action is lagging. Examples include climate emergency declarations issued by scientists6,7,8, social movements9,10,11,12, cities and municipalities13,14,15, and parliaments, and also recently declarations of a biodiversity emergency1,16. The United Nations Environment Programme has been labelling both climate change and biodiversity as emergencies on its websites since 2019, and issued a report to “tackle the climate, biodiversity and pollution emergencies” in 202117. Furthermore, in a state of the planet address in December 2020, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres declared a climate and biodiversity emergency, normalizing these frames within the multilateral governance arena. Illustrative examples of these two ways of employing emergency frames are given in Table 1.

Climate emergency frames are becoming especially prominent, as reflected in the results of a survey conducted by the United Nations Development Programme in 2020, which found that 64% of people around the world thought of climate change as an emergency18. The diffusion of emergency frames has multiple drivers, both scientific (for example, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C in 20182,6) and socio-political (for example, social mobilization by climate movements). Importantly, emergency frames have a history in domains beyond sustainability, most obviously in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic19,20, but also in disaster management21,22,23,24, security25,26, migration27 and even colonialism28,29. The politics of emergency frames in sustainability is, therefore, unavoidably entangled with broader issues and debates.

Conceptualizing emergency frames

A ‘frame’ refers to an interpretive lens, comprising symbols, categorizations and stories for delimiting and making sense of an issue by providing comprehension and suggesting responses30,31. The concept of frames emerged within multiple disciplines, including language studies, sociology, psychology and political science32. A frame conveys the essence of a controversy33, shaping how controversies are dealt with by highlighting certain features of an issue but obscuring others34. Framing influences attitudes and behaviours of individuals and groups on political issues35. As such, frame competitions can arise22, which may risk capture by political elites but can also afford new opportunities to comprehend problems through challenges to dominant frames. However, any single frame can have varying effects on people, depending on, for example, their ideological affiliation36, as observed in climate policy37,38.

An emergency frame is a way of constructing a political issue as exceptional and urgent, which demands action to avoid catastrophe7,29,39. Frames have been found to play a key role in the politics of disasters/crises40, as various actors use frames to politicize events and assign or deflect blame41,42. Declarations of emergency may also enable the allocation of extraordinary powers and shifts in authority (including to unelected officials). Yet, defining what exactly constitutes an emergency is not straightforward, especially for emergencies that are more open-ended. For example, in climate emergency declarations, framing work involves ‘crisification’2, invoking specific qualities of unpredictability, irreversibility, rapid change and critical juncture43, but importantly also hope43 that action can lead to better outcomes. Recently, multiple emergency frames are being bundled (for example, climate and biodiversity as interconnected emergencies44, climate change as a public health8,45 and human rights46 emergency, links between climate change and racism47).

The notion of ‘emergency’ emphasizes a need for action or response to an acute threat or crisis. Yet, the very notion of emergency makes subtle assumptions about normalcy in the face of such threats. For emergency-as-reaction, the typical imperative is for a return to pre-existing conditions43. In contrast, emergency-as-strategy typically assumes the untenability of the status quo, where this status quo is ‘othered’ to observe its pathology and choose anew. In other words, emergency-as-strategy is about creating an exception to the norm as a political intervention to make an existing situation visible in a new way. Thus, despite emergency frames being central in both situations, the politics of emergency may be very different, particularly since climate or biodiversity emergencies are open-ended and without quick resolution, suggesting ongoing political struggles and complex consequences. Nonetheless, emergency-as-reaction may also have potentially far-reaching consequences, as witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic with reconfigurations of legal authority, expanded use of militaries in domestic tasks and expanded surveillance19,48,49.

Who is involved in defining an emergency is inherently political. This may involve networks of experts, the media, politicians and the general public. The construction of an emergency frame involves sense-making (that is, articulation and promotion of an explanatory narrative) within uncertain situations and incomplete information50,51. From a social constructivist perspective, emergencies are not treated as objectively existing, but rather as co-constructed through shared experiences, perceptions and communications of threat and urgency24,52. Elite capture of such deliberations can, however, lead to a singular focus and reductive logic that overlooks trade-offs across diverse issues in heterogeneous societies, and also privileges centralized state responses over pluralistic responses that could ultimately be more effective53,54,55. Notably for climate emergency, actors outside the mainstream (for example, youth movements and small local governments13,15) have played a crucial role, often closely tied to cognate demands for justice and equality. These demands have been embedded in the ‘green (new) deals’ currently debated in Europe56 and North America57. Clearly power plays a role in framing emergencies, but this may be more complex than simply reinforcing pre-existing asymmetries, suggesting that power should be seen within a longer-term perspective of evolving political struggle, that is, over which emergency, for whom and according to whom?

Also bound up in the notion of emergency are claims about the pace and scale of response. Emergency frames imply a need for rapid and substantive action that matches the scale of threat. For emergency-as-reaction, responses often attempt to overcome immediate danger, although doing so may require transformative action to address root causes of vulnerability58. There are also widespread examples of responses to emergency-as-reaction being used to advance the political goals of powerful incumbent actors (for example, public education reforms in New Orleans post-Hurricane Katrina)59. For emergency-as-strategy, the deployment of emergency frames is geared towards stimulating urgency (for example, speed) and increased ambition of action in the absence of immediate danger. Thus, a key difference between emergency-as-reaction and emergency-as-strategy is that the former centres on a response to impacts that have manifestly occurred, whereas the latter strategically aims to avoid impacts in the future. These stances can become enmeshed, as shown in the cases of the Australian wildfires and water-related crises in India (Table 1) where specific crisis events came to support the strategic deployment of emergency frames, through locating the source of crises within broader narratives about climate emergency.

Variation in political effects

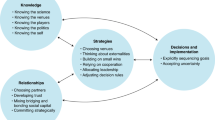

The political effects of emergency frames were found to vary across five key dimensions (Fig. 1): (1) engagement among mass publics, including affect, emotions and arousal, motivations, and behaviours; (2) empowerment or disempowerment of actors, including ability to accomplish tasks, influence over others and patterns of inclusion/exclusion; (3) exercise of formal political authority, including effects on rule of law, consent/legitimacy and democratic accountability; (4) reshaping of discourse, including effects on public attention, political imaginaries and embedding of new ideas (for example, transformation); and (5) impacts on institutions, including strengthening or weakening existing institutions, and new mechanisms of steering. This typology enables systematic analysis of variation in effects, both within individual cases and comparatively as illustrated in Boxes 1–3, which can support the derivation of contextually grounded policy implications.

Engagement among mass publics

Emergency frames typically aim to increase the engagement of mass publics by generating attention and political activism, changing perceptions of urgency and risk, and building support for action. This can have complex psychological and cognitive consequences, involving affect (that is, state of mind and bodily experience), emotions and psychological arousal (for example, distress, excitement), which influence motivation for action. Engagement may increase or decrease, and vary for different individuals and groups.

Emergency frames can be energizing, as witnessed by the diffusion of climate emergency declarations and school student strikes, which can imbue inspiration, hope43 and a sense of efficacy60. But emergency frames can also be emotionally draining and create exhaustion, anxiety, guilt and fear2,11,61,62. Fear can have ambiguous and sometimes counterproductive effects on motivation to act63,64. Research on climate change and fear reveals that existential threats can “increase commitment to one’s worldview, self-esteem, and relationships, and increase defence of these entities when threatened”65. In such situations, people are likely to cling to existing thoughts, values and ideology, regardless of necessary action to address the crisis. Existential fear can also trigger increased commitment to action from those already concerned about certain issues, such as protest or the pursuit of goals that outlive individuals (for example, change in legislation, new infrastructure)66. Recently, some scholars have questioned whether concerns about fear-based messaging are overstated67, suggesting the need to strike a balance between animating a sense of urgency and triggering denial or inaction2.

Typically, the notion of emergency is associated with a threat to survival or health, triggering heightened states of psychological arousal (for example, distress, excitement). However, arousal is a threshold property, and overwhelming this threshold closes down the capability to respond68. In cases of emergency-as-reaction, arousal is important to address an immediate threat. In cases of emergency-as-strategy, arousal will be difficult to sustain and could risk overwhelming some people with distress even while animating others. Arousal is related to the sense of urgency invoked by emergency. Yet, there is ambiguous evidence regarding the effect of time pressure on behavioural responses, including risk of inaction caused by optimism bias67,69 or increased willingness to cope with risk70. Under COVID-19, frustrations with sustained restrictions have emerged, even where initial solidarity was present. This suggests that motivation for collective action in response to sustained crises may erode over time (although evidence here is ambiguous71). Mismatches between rhetoric and action could also have adverse motivational consequences for mass publics (for example, disappointment, resignation), which could undermine the potential for future public ambition—what if the measure of last resort has been exhausted without the desired effects?

The deployment of emergency frames is underpinned by an assumption that recognizing emergency will promote radical responses, including individual behaviour change, norm following and policy support. While this could occur for emergency-as-reaction where behavioural responses are temporary, scholarly literature is mixed as to whether emergency-as-strategy will have similar effects. For example, despite widespread apocalyptic language in climate communication, policy interventions rarely move beyond technocratic, incremental interventions72. Dystopic imagery appears to have limited ability to change individual actions64,73,74. Elsewhere, a ‘boomerang effect’ has been observed in areas such as health and anti-littering campaigns, where psychological reactance or assertions of freedom increases the behaviour that is intended to be reduced75. Conversely, exposure to emergency frames (for example, as measured by familiarity with Greta Thunberg) may increase the propensity to engage in climate activism60. This suggests a complex range of possible consequences for engagement among mass publics, and variation among social groups (for example, based on gender and cultural worldview)76.

Empowerment or disempowerment of actors

Empowerment or disempowerment of actors refers to shifts in power that either increase (empower) or decrease (disempower) the power of a particular actor relative to others. This centres on the ‘power to’ accomplish tasks, as contrasted against ‘power with’ (that is, cooperation) or ‘power over’ others (that is, domination)77. Emergency frames may have different consequences for different actors, relating to the ability to accomplish tasks, level of influence over others and patterns of inclusion/exclusion.

Empowerment/disempowerment is shaped by the type of emergency frame deployed. For example, different combinations of actors and goals are involved in the emergency-as-reaction and emergency-as-strategy cases in Table 1. Emergency-as-reaction may empower those with existing responsibility for emergency response (for example, emergency services, certain government agencies, non-governmental organizations) through the wielding of formal powers and moral authority. The pressure to ‘return to normal’ may disempower those seeking ambitious changes or a radical break with the past. Emergency-as-strategy may empower new actors seeking to claim authoritative status (for example, scientists) and influence other actors (for example, social movements), or create a mandate for decisive action (for example, governments/parliaments). This approach also seeks to disempower those opposing radical action (for example, certain businesses, lobbyists, politicians).

Through mobilizing climate emergency frames, new actors seek influence in climate debates. Perhaps most prominently, Fridays For Future has elevated school students as a new category of actors through claiming (moral) power of youth, undermining that of existing leaders10. Extinction Rebellion has also become prominent in some countries. These actors argue that a climate and biodiversity emergency warrants extraordinary mobilization of attention and resources7. While they have received public attention and made some political gains (for example, creation of a UK citizen’s climate assembly), it is unclear whether they have mobilized necessary resources or power to create systemic political change. Furthermore, there have been struggles over empowerment. For example, in Australia, the credibility and authority of ‘youth’ has been challenged by actors holding formal authority (for example, the prime minister)78.

Further insights regarding emergency-as-strategy arise in the context of racism, colonization and violence. Black Lives Matter activists deployed the idea of emergency to draw attention to the normalization of ordinary violence in the context of institutionalized racism. Here, “naming a state of emergency is to recognize and interrupt an already existing condition of existence that mixes the endemic and evental”43. The act of declaring an emergency is used to build recognition of unendurable conditions of life that have long been ignored or denied. Indigenous studies scholars have criticized the deployment of emergency frames that rely on settler colonial social structures and deny the legacy of violence and loss experienced by Indigenous peoples79. These insights show that the potential for empowerment/disempowerment through emergency frames is contingent on broader social structures (for example, institutionalized racism, histories), but also the possibilities for society-wide action that may arise through naming long-ignored circumstances.

Relatedly, emergency frames may also resonate with longer-term patterns of inclusion/exclusion. Emergency frames demanding sweeping action by government could afford political coverage for unpopular actions and overcome veto points59. Yet, poor and/or minority communities may lose voice if emergency frames are oriented towards quick fixes53. For example, within international development, emergency frames have been criticized for potentially undermining developing states’ sovereignty and reinforcing inequalities80. This suggests tensions between emergency frames that empower certain actors while disempowering others.

Exercise of formal political authority

Exercise of formal political authority refers to instances where governments compel other actors to take action, through formal or normative authority. While this dimension partially overlaps with empowerment/disempowerment (which focuses on the relative balance in power between actors), the exercise of formal political authority relates to the use or intensification of power by a particular (core) actor: government. It thus centres on ‘power over’ others (for example, domination, exercise or threat of violence)77, relating to issues of rule of law, consent/legitimacy and democratic accountability.

Emergency-as-reaction may bolster the political authority of governments in a particular crisis. However, this is unlikely to be straightforward as seen, for example, by the Brazilian government’s recent efforts to downplay major fires in the Amazon and associated resistance to emergency action. On the other hand, the unprecedented imposition of restrictions within COVID-19 pandemic responses across many areas of social life (for example, gathering, work, travel) shows that swift and radical action is possible. Yet, over time the legitimacy of these restrictions may erode. In relation to emergency-as-strategy, governments may resist adopting climate emergency stances to avoid expectations for swift and strong action. For example, despite the unprecedented scale and impact of the Australian wildfires in 2019–2020, the national government has resisted calls for climate action (Table 1) and dismissed students declaring climate emergency (see previous section). Under conditions of emergency, such as COVID-19, governments may extend authority into new areas (for example, surveillance), which may be in tension with liberal values48. Moreover, a legitimacy gap could arise if actions in response to a declared emergency are not proportionate to the scale of the threat—a dynamic already becoming visible where these declarations have been made by governments.

Many scholars express concerns over the democratic implications of emergency frames. A frequently raised issue is threats stemming from rapid decisions that foreclose democratic deliberation, fast-track action, and remove normal checks and balances29,39,49. Some argue that this can lead to new forms of control, potentially advancing securitized or militarized responses81. Within security studies, emergency governance is associated with overcoming constraints of the rule of law. This raises questions about the use of emergency frames, particularly under extended or permanent states of emergency25,29, and where emergency tools extend into non-traditional domains25,26 such as sustainability. Scholars in the ‘Copenhagen School’ draw attention to the ways in which speech acts can lead to an issue being portrayed as a security threat and ‘securitized’, thereby permitting extraordinary measures to be taken82. Emergency powers can enable state control over issues through means of violence, for example, to repress insurgencies or unrest. A historical perspective on states of emergency reveals the appropriation of the concept by capitalist and colonial states to repress class struggles and quell popular mobilization29. This legacy underlies many concerns regarding emergency declarations adopted as a state-led political strategy, due to tensions with liberal democratic values19,49. Nonetheless, while framing climate change as an emergency is viewed as an indicator of securitization by some83,84, others find limited evidence of this85.

Similar concerns in sustainability have arisen about whether the narrow framing of ‘climate emergency’ empowers a technocratic elite and undermines a plurality of goals and political creativity necessary to address justice and well-being concerns bound up in sustainability53,54. Deploying emergency-as-strategy could normalize a pre-emptive logic that could “close down debate and legitimize otherwise unpalatable options”86. Conversely, declarations of emergency that emerge from civil society may be viewed as a democratization of governance within gridlocked political systems. A recent review of climate emergency declarations by municipalities found no tendency towards authoritarian governance. Rather, participation was shaped by the history of engagement, type of political system and role of civil society in shaping political outcomes85. Moreover, a key question for emergency frames in sustainability is whether they are expected to usher in new modes of decision-making, or simply faster decision-making using existing political authority.

Reshaping of discourse

Discourse involves broad sets of ideas and conceptual schema by which meaning is communicated, which are reproduced or transformed through social practices87. While a frame is a specific interpretive device, discourse refers to the broader landscape of ideas and practices within which specific frames are situated. An emergency frame might reinforce or conflict with a dominant discourse, or influence the relationship between competing discourses (for example, directing public attention, introducing new imaginaries, embedding new ideas).

Emergency frames may contribute to reshaping dominant discourses (for example, business as usual), but this is not guaranteed. For emergency-as-reaction, such frames may fail to reshape existing discourse if they simply focus on returning to normal (see the Australian and Indian cases in Table 1). In contrast, emergency-as-strategy seeks to disrupt discursive stability, although it also contends with open-ended issues that lack a clear beginning or end and may not fit typical public understandings of an emergency. For example, ‘crisification’ of climate change may have been a key factor influencing discourse informing the Paris Agreement88. But policy scholars have long observed that public attention is ephemeral89, and argued that emergency involves struggle over meaning90. Thus, emergency frames may require ongoing political work to sustain discursive effects. Whether this will occur for current claims about climate and biodiversity emergencies is unclear because discourse change takes time.

Emergency frames can also introduce new imaginaries. These are (largely subconscious) images of the past or future imbued with meaning, narrative and norms about a community91, which make sense of changes beyond immediate experience92,93. Emergency-as-strategy has been criticized for reflecting technocratic53,54 and even apocalyptic94 imaginaries, which fail to generate alternative ideas about the future. The language “depicts the future to be both utterly uncertain and yet eschatological…[where] The next catastrophe is certain, but until it will have happened one cannot predict anything about it”95. Emergency frames risk obscuring root causes (for example, capitalism, viewing nature as an inexhaustible resource) through imaginaries involving rapid solutions that perpetuate the status quo, potentially fostering a depoliticized discourse that is void of imagination79,96. Yet, emergency can also invoke imaginaries that break with the past and create hope for the future43,97.

A key question is whether emergency frames usefully embed new ideas in prevailing discourse. For example, emergency-as-strategy could instil greater imperative for climate action in sluggish political systems, or open up new rhetorical strategies to avoid the easy dismissal of climate action98,99. But it could also prematurely close down discursive space in the search for concrete solutions94, and even trigger counterdiscourses (for example, charges of alarmism or reactionary conservatism) that stall action and reinforce polarization. Whether emergency is accommodated in sustainability discourse may, therefore, rest on the creation and acceptance of new notions of emergency that go beyond technocratic management and embrace normative directionality about the future. For example, the notion of a ‘long emergency’100 provides impetus for such an approach. This might also be an important step towards governance in the Anthropocene where deep time horizons become a key concern101.

Impacts on institutions

Institutions refer to “rights, rules, and decision-making procedures that gives rise to a social practice, assign roles to the participants…and guide interactions among occupants of these roles”102. Thus, institutions stabilize social expectations and provide frameworks within which complex social and political activity becomes possible. While institutions are both formal and informal, we focus on the more readily observable formal aspects. Emergency frames may work within existing institutions (for example, constitutions, resource governance arrangements) or seek to disrupt them (for example, calls for extraordinary action or new mechanisms of steering action), raising questions about the consequences for existing institutions (for example, strengthening, weakening).

Emergency frames could strengthen policy portfolios core to state sovereignty, such as essential services, homeland security, intelligence, military and finance, but perhaps also others linked to a particular emergency (for example, health, infrastructure). Military involvement is now used in situations of emergency-as-reaction to extreme climate impacts (for example, hurricanes, floods, fires), which may increase as climate change threatens national security83,103. While proponents of climate and/or biodiversity emergency frames may hope that emergencies elevate sustainability policy portfolios, it seems equally likely that these will be subordinated to areas critical to state security. At an international level, emergency frames could strengthen institutional arrangements around specific issues. For example, biodiversity emergency could strengthen the fragmented global assemblage of assessments, treaties and agreements. Climate emergency could accelerate the formation of new assemblages around geoengineering particularly through re-appropriating demands for urgent action86,104.

Emergency frames may precipitate new mechanisms of steering action. For example, disaster/crisis scholars observe that ‘focusing events’105 (such as disasters106) may generate new frames that drive policy change. Public inquiries following disasters/crises may also lead to policy or legislative change. For open-ended emergencies (for example, climate, biodiversity) this is less clear. Institutional effects may depend on pre-existing capacities, such as the capacity to learn from experience and public inquiries107 and anticipate future problems. Municipalities declaring climate emergency may establish new mechanisms to influence planning and infrastructure decisions, such as citizens’ assemblies85. Yet, hopeful expectations should be tempered by the typically slow nature of institutional change due to path dependencies, inefficient adaptation to new circumstances, ‘lock-in’ of institutions with technologies and behaviours, and ephemeral opportunities for deliberate change108.

Implications and next steps

It is clear that emergency frames can have diverse effects in sustainability science and politics. It also seems likely that the use of emergency frames will persist, given growing disruption of the Earth system and public demand for ambitious action on issues such as climate change and biodiversity. This Review provides a foundation for future work to systematically examine the political effects of emergency frames, and builds a shared vocabulary for comparative analysis.

The question of whether emergency frames enhance or reduce prospects for mobilizing ambitious action defies straightforward answer. Evidence is ambiguous and sometimes conflicting, and different combinations of effects may occur in different contexts. Our illustrative cases (Table 1 and Boxes 1–3) provide at best limited evidence that emergency frames lead to new forms of ambitious and/or transformative action in the short term. Although this does not mean that indirect or longer-term effects (for example, enduring shifts in discourse or institutional change) will not occur. Over time, emergency frames could generate new discourses that draw attention to irreversible consequences of inaction and existential imperatives for action, or at least increase public awareness. Yet, emergency frames could legitimate new repertoires of action not intended by proponents, such as geoengineering86,109,110. Deployment of emergency frames also risks triggering exclusionary responses due to prioritization of urgency over deliberation. Current literature shows concerns over technocratic forms of knowledge and decision-making that run counter to calls to pluralize knowledge and action in response to diverse social, ecological and political concerns53. Long-term mobilization for issues such as climate change and biodiversity loss (for example, ‘long emergencies’100) begs the question of how long emergency frames can be credibly and meaningfully sustained.

A key next step is to look in depth within specific bodies of literature (for example, disciplines covered here, as well as particular fields such as disaster/crisis management and securitization) to draw out further conceptual and comparative insights. In doing so, it will be important to return to a broad view of multiple political effects as highlighted in Fig. 1. Another next step is to systematically review each of the five dimensions of the typology. Current evidence is diverse, patchy and sometimes contradictory. Our focus here has been on an interdisciplinary synthesis of evidence to identify points of agreement/disagreement and map the overall contours of the problem. Systematic evidence assessment within each effect dimension would be a valuable next step to generate hypotheses and identify scope conditions that can help to disentangle this complex picture.

Emergency frames are both an empirical claim about the world and a political intervention. As a strategy for generating collective action, this approach is complicated by existing ideas and practices connected to the notion of emergency, even though declarations of emergency by non-state actors may seek a new type of emergency politics that foregrounds ethical concerns. Commonly, emergency frames initiated by governments have an uncomfortable relationship with governing practices that have historically been used to exercise transgression of liberties, and even violence and oppression. Newer emergency frames advocated by civil society have come to be seen as a tool of political struggle towards sustainability and justice. Scholars frequently view government-initiated emergency with caution or even cynicism, but emergencies called by civil society challenge us to think about emergency in a new light, potentially even re-theorizing the very notion as a potential tool of emancipation within a longer-term perspective of societal transformations.

Scholars, policymakers and civil society should not be too quick to embrace nor discard emergency frames, as they may have different implications depending on time frame and context (Box 4). Some contexts may be able to absorb the risk of adverse consequences (for example, robust democracies), whereas others may be less well placed to do so48 (for example, those with authoritarian tendencies or strong political polarization). In the strategic deployment of emergency frames, there is a delicate balance between maintaining discomfort, but not overwhelming people and decision-makers. Such productive friction probably requires balancing critical calls for radical change with concrete (even if imperfect) actions, and positive or hopeful messages side by side. This balance will of course be challenging to navigate, will differ across societies and will continuously evolve. Within this mix, emergency frames may have a key, but probably only partial, role to play—relying entirely on emergency frames to motivate collective sustainability action may risk seizing up the gears of society and politics rather than lubricating them.

References

Tickner, D. et al. Bending the curve of global freshwater biodiversity loss: an emergency recovery plan. BioScience 70, 330–342 (2020).

Wilson, A. J. & Orlove, B. What do We Mean When We Say Climate Change is Urgent? (Earth Institute, Columbia Univ., 2019). This paper reflects on the notion of ‘urgency’ in climate change debates, finding that it acts as a boundary object between science, policy, civil society and media, but can also trigger a range of psychological effects.

Grant, M. J. & Booth, A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info. Libr. J. 26, 91–108 (2009).

Enqvist, J. P. & Ziervogel, G. Water governance and justice in Cape Town: an overview. WIREs Water 6, e1354 (2019).

Australian Government Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements Report (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020).

Ripple, W. J., Wolf, C., Newsome, T. M., Barnard, P. & Moomaw, W. R. World scientists’ warning of a climate emergency. BioScience 70, 8–12 (2019). This paper asserts that the world is facing a climate emergency, drawing on macro trends across a variety of Earth system processes, arguing that scientists have a moral obligation to bring this to public attention, and is signed by over 11,000 scientists.

Spratt, D. & Sutton, P. Climate Code Red: The Case for Emergency Action (Scribe Publications, 2008).

Solomon, C. G. & LaRocque, R. C. Climate change—a health emergency. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 209–211 (2019).

Gilding, P. Why I welcome a climate emergency. Nature 573, 311 (2019).

Holmberg, A. & Alvinius, A. Children’s protest in relation to the climate emergency: a qualitative study on a new form of resistance promoting political and social change. Childhood 27, 78–92 (2020).

Skrimshire, S. Activism for end times: millenarian belief in an age of climate emergency. Polit. Theol. 20, 518–536 (2019).

Thackeray, S. J. et al. Civil disobedience movements such as school strike for the climate are raising public awareness of the climate change emergency. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 1042–1044 (2020).

Cohen, D. A. Confronting the urban climate emergency: critical urban studies in the age of a green new deal. City 24, 52–64 (2020).

Davidson, K. et al. The making of a climate emergency response: examining the attributes of climate emergency plans. Urban Clim. 33, 100666 (2020).

Chou, M. Australian local governments and climate emergency declarations: reviewing local government practice. Aust. J. Publ. Adm. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12451 (2020).

Roe, D. Biodiversity loss—more than an environmental emergency. Lancet Planet. Health 3, e287–e289 (2019).

Making Peace with Nature: A Scientific Blueprint to Tackle the Climate, Biodiversity and Pollution Emergencies (United Nations Environment Programme, 2021).

The Peoples’ Climate Vote (United Nations Development Programme & Univ. Oxford, 2021).

Maerz, S. F., Lührmann, A., Lachapelle, J. & Edgell, A. B. Worth the Sacrifice? Illiberal and Authoritarian Practices During COVID-19 (The Varieties of Democracy Institute, Univ. Gothenburg, 2020).

Manzanedo, R. D. & Manning, P. COVID-19: lessons for the climate change emergency. Sci. Total Environ. 742, 140563 (2020).

’t Hart, P., Tindall, K. & Brown, C. Crisis leadership of the Bush presidency: advisory capacity and presidential performance in the acute stages of the 9/11 and Katrina crises. Pres. Stud. Q. 39, 473–493 (2009).

Boin, A., ’t Hart, P. & McConnell, A. Crisis exploitation: political and policy impacts of framing contests. J. Eur. Public Policy 16, 81–106 (2009).

Tierney, K., Bevc, C. & Kuligowski, E. Metaphors matter: disaster myths, media frames, and their consequences in Hurricane Katrina. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 604, 57–81 (2006).

Lizarralde, G., Johnson, C. & Davidson, C. Rebuilding after Disasters: From Emergency to Sustainability (Routledge, 2010).

Armitage, J. State of emergency: an introduction. Theory Cult. Soc. 19, 27–38 (2002).

Scarry, E. Thinking in an Emergency (WW Norton, 2012).

Lindley, A. Crisis and Migration: Critical Perspectives (Routledge, 2014).

Hussain, N. The Jurisprudence of Emergency: Colonialism and the Rule of Law (Univ. Michigan Press, 2019).

Neocleous, M. The problem with normality: taking exception to “permanent emergency”. Alternatives 31, 191–213 (2006). This paper provides a historical overview of the deployment of emergency declarations by governments as a tool for political oppression.

Goffman, E. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organisation of Experience (Northeastern Univ. Press, 1986).

van Hulst, M. & Yanow, D. From policy “frames” to “framing”: theorizing a more dynamic, political approach. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 46, 92–112 (2016).

Borah, P. Conceptual issues in framing theory: a systematic examination of a decade’s literature. J. Commun. 61, 246–263 (2011).

Rein, M. & Schön, D. Frame-critical policy analysis and frame-reflective policy practice. Knowl. Policy 9, 85–104 (1996).

Schön, D. A. & Rein, M. Frame Reflection: Toward the Resolution of Intractable Policy Controversies (Basic Books, 1994).

Chong, D. & Druckman, J. N. Framing theory. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 10, 103–126 (2007).

Slothuus, R. & de Vreese, C. H. Political parties, motivated reasoning, and issue framing effects. J. Polit. 72, 630–645 (2010).

Wiest, S. L., Raymond, L. & Clawson, R. A. Framing, partisan predispositions, and public opinion on climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 31, 187–198 (2015).

Nisbet, M. C. Communicating climate change: why frames matter for public engagement. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 51, 12–23 (2009).

Hodder, P. & Martin, B. Climate crisis? The politics of emergency framing. Econ. Polit. Wkly 44, 53–60 (2009).

Boin, A., McConnell, A. & ‘t Hart, P. Governing after Crisis: The Politics of Investigation, Accountability and Learning (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008).

Brändström, A. & Kuipers, S. From ‘normal incidents’ to political crises: understanding the selective politicization of policy failures. Gov. Oppos. 38, 279–305 (2003).

Hood, C. The Blame Game: Spin, Bureaucracy, and Self-preservation in Government (Princeton Univ. Press, 2011).

Anderson, B. Emergency futures: exception, urgency, interval, hope. Sociol. Rev. 65, 463–477 (2017). This paper discusses how emergency declarations can function as actions of hope, as they can allow conditions in the present to be recognized as emergencies while envisioning a future that is ‘other’ than the present.

Mori, A. S. Advancing nature‐based approaches to address the biodiversity and climate emergency. Ecol. Lett. 23, 1729–1732 (2020).

Hanna, L. Climate change: past and projected threats to food and water security = public health emergency. Eur. J. Public Health 30, ckaa165.010 (2020).

Mapp, S. & Gatenio Gabel, S. The climate crisis is a human rights emergency. J. Hum. Rights Soc. Work 4, 227–228 (2019).

Tuana, N. Climate apartheid: the forgetting of race in the Anthropocene. Crit. Philos. Race 7, 1 (2019).

Greitens, S. C. Surveillance, security, and liberal democracy in the post-COVID world. Int. Organ. 74, E169–E190 (2020).

Thomson, S. & Ip, E. C. COVID-19 emergency measures and the impending authoritarian pandemic. J. Law Biosci. 7, lsaa064 (2020).

Boin, A., Stern, E. & Sundelius, B. The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership Under Pressure (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2016).

Van Buuren, A., Vink, M. & Warner, J. Constructing authoritative answers to a latent crisis? Strategies of puzzling, powering and framing in Dutch climate adaptation practices compared. J. Comp. Policy Anal. 18, 70–87 (2016).

Brinks, V. & Ibert, O. From corona virus to corona crisis: the value of an analytical and geographical understanding of crisis. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 111, 275–287 (2020).

Hulme, M. Climate emergency politics is dangerous. Issues Sci. Technol. 36, 23–25 (2019). This paper argues that climate emergency frames the narrow scope of sustainability concerns, which leads to technocratic responses and undermines the possibility for including plural perspectives in shaping action towards sustainability.

Hulme, M., Lidskog, R., White, J. M. & Standring, A. Social scientific knowledge in times of crisis: what climate change can learn from coronavirus (and vice versa). WIREs Clim. Change 11, e656 (2020).

Funtowicz, S. From risk calculations to narratives of danger. Clim. Risk Manag. 27, 100212 (2020).

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: The European Green Deal (European Commission, 2019).

Ocasio-Cortez, A. House Resolution 109—116th Congress (2019–2020): Green New Deal Resolution—Recognizing the duty of the Federal Government to Create a Green New Deal (United States Congress, 2019).

Pelling, M. Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation (Routledge, 2011).

Klein, N. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (Knopf Canada, 2007).

Sabherwal, A. et al. The Greta Thunberg effect: familiarity with Greta Thunberg predicts intentions to engage in climate activism in the United States. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 51, 321–333 (2021).

Kleres, J. & Wettergren, Å. Fear, hope, anger, and guilt in climate activism. Soc. Mov. Stud. 16, 507–519 (2017). This paper explores the emotions of youth climate activists, finding that these actors develop strategies to manage complex combinations of negative and positive emotions, giving rich insights from in-depth qualitative investigation.

Goodwin, J., Jasper, J. M. & Polletta, F. in The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements (eds Snow, D. A. et al.) 413–432 (Blackwell, 2007).

Ruiter, R. A. C., Abraham, C. & Kok, G. Scary warnings and rational precautions: a review of the psychology of fear appeals. Psychol. Health 16, 613–630 (2001).

O’Neill, S. & Nicholson-Cole, S. “Fear won’t do it”: promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Sci. Commun. 30, 355–379 (2009).

Pyszczynski, T., Lockett, M., Greenberg, J. & Solomon, S. Terror management theory and the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Humanist. Psychol. 61, 173–189 (2021).

Wolfe, S. E. & Tubi, A. Terror management theory and mortality awareness: a missing link in climate response studies? WIREs Clim. Change 10, e566 (2019).

Hornsey, M. J. & Fielding, K. S. Understanding (and reducing) inaction on climate change. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 14, 3–35 (2020).

Weick, K. E. Small wins: redefining the scale of social problems. Am. Psychol. 39, 40–49 (1984).

Sharot, T. The optimism bias. Curr. Biol. 21, R941–R945 (2011).

Madan, C. R., Spetch, M. L. & Ludvig, E. A. Rapid makes risky: time pressure increases risk seeking in decisions from experience. J. Cogn. Psychol. 27, 921–928 (2015).

Michie, S., West, R. & Harvey, N. The concept of “fatigue” in tackling COVID-19. Br. Med. J. 371, m4171 (2020).

Methmann, C. & Rothe, D. Politics for the day after tomorrow: the logic of apocalypse in global climate politics. Secur. Dialogue 43, 323–344 (2012).

Moser, S. C. & Dilling, L. Making climate HOT. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 46, 32–46 (2004).

Lowe, T. et al. Does tomorrow ever come? Disaster narrative and public perceptions of climate change. Public Underst. Sci. 15, 435–457 (2006).

Byrne, S. & Hart, P. S. The boomerang effect: a synthesis of findings and a preliminary theoretical framework. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 33, 3–37 (2009).

Hung, L.-S. & Bayrak, M. M. Comparing the effects of climate change labelling on reactions of the Taiwanese public. Nat. Commun. 11, 6052 (2020).

Partzsch, L. ‘Power with’ and ‘power to’ in environmental politics and the transition to sustainability. Environ. Polit. 26, 193–211 (2017).

Feldman, H. R. A rhetorical perspective on youth environmental activism. J. Sci. Commun. 19, C07 (2020).

Anson, A. Master metaphor: environmental apocalypse and settler states of emergency. Resil. J. Environ. Hum. 8, 60–81 (2021).

Pupavac, V. The politics of emergency and the demise of the developing state: problems for humanitarian advocacy. Dev. Pract. 16, 255–269 (2006).

McDonald, M. After the fires? Climate change and security in Australia. Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 56, 1–18 (2020).

Buzan, B., Wæver, O. & de Wilde, J. Security: A New Framework for Analysis (Lynne Rienner, 1998).

Oels, A. in Climate Change, Human Security and Violent Conflict (eds Scheffran, J. et al) 185–205 (Springer, 2012).

Trihartono, A., Viartasiwi, N. & Nisya, C. The giant step of tiny toes: youth impact on the securitization of climate change. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 485, 012007 (2020).

Ruiz Campillo, X., Castan Broto, V. & Westman, L. Motivations and intended outcomes in local governments’ declarations of climate emergency. Polit. Gov. 9, 17–28 (2021).

Markusson, N., Ginn, F., Singh Ghaleigh, N. & Scott, V. ‘In case of emergency press here’: framing geoengineering as a response to dangerous climate change. WIREs Clim. Change 5, 281–290 (2014). Using the example of geoengineering, this paper argues that emergency frames can provide pre-emptive justification for certain solutions and foreclose deliberations in environmental governance.

Hajer, M. A. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process (Oxford Univ. Press, 1995).

Paglia, E. The socio-scientific construction of global climate crisis. Geopolitics 23, 96–123 (2018).

Weible, C. M. & Sabatier, P. A. Theories of the Policy Process (Westview, 2017).

‘t Hart, P. & Tindall, K. Framing the Global Economic Downturn: Crisis Rhetoric and the Politics of Recessions (ANU E Press, 2009).

Diehl, P. Temporality and the political imaginary in the dynamics of political representation. Soc. Epistemol. 33, 410–421 (2019).

Milkoreit, M. in Reimagining Climate Change (eds Wapner, P. & Elvar, H.) 171–191 (Routledge, 2016).

Norgaard, K. M. The sociological imagination in a time of climate change. Glob. Planet. Change 163, 171–176 (2018).

Swyngedouw, E. Apocalypse forever? Theor. Cult. Soc. 27, 213–232 (2010).

Opitz, S. & Tellmann, U. Future emergencies: temporal politics in law and economy. Theor. Cult. Soc. 32, 107–129 (2015).

Schinkel, W. The image of crisis: Walter Benjamin and the interpretation of ‘crisis’ in modernity. Thesis Eleven 127, 36–51 (2015).

Slaughter, R. A. Sense making, futures work and the global emergency. Foresight 14, 418–431 (2012).

Wilkinson, C. & Clement, S. Geographers declare (a climate emergency)? Aust. Geogr. 52, 1–18 (2021).

Spoel, P., Goforth, D., Cheu, H. & Pearson, D. Public communication of climate change science: engaging citizens through apocalyptic narrative explanation. Tech. Commun. Q. 18, 49–81 (2008).

Orr, D. W. Dangerous Years: Climate Change, the Long Emergency, and the Way Forward (Yale Univ. Press, 2016).

Biermann, F. The Anthropocene: a governance perspective. Anthr. Rev. 1, 57–61 (2014).

Young, O. R., King, L. A. & Schroeder, H. Institutions and Environmental Change: Principal Findings, Applications, and Research Frontiers (MIT, 2008).

McDonald, M. Discourses of climate security. Polit. Geogr. 33, 42–51 (2013).

Asayama, S., Bellamy, R., Geden, O., Pearce, W. & Hulme, M. Why setting a climate deadline is dangerous. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 570–572 (2019).

Kingdon, J. W. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies (Pearson Education, 2014).

Birkland, T. A. Lessons of Disaster: Policy Change After Catastrophic Events (Georgetown Univ. Press, 2006).

Eburn, M. & Dovers, S. Learning lessons from disasters: alternatives to royal commissions and other quasi-judicial inquiries. Aust. J. Publ. Admin. 74, 495–508 (2015).

Patterson, J. J. Remaking Political Institutions: Climate Change and Beyond (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Sillmann, J. et al. Climate emergencies do not justify engineering the climate. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 290–292 (2015).

Horton, J. B. The emergency framing of solar geoengineering: time for a different approach. Anthr. Rev. 2, 147–151 (2015).

van Oldenborgh, G. J. et al. Attribution of the Australian bushfire risk to anthropogenic climate change. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 941–960 (2021).

Lockie, S. Sociological responses to the bushfire and climate crises. Environ. Soc. 6, 1–5 (2020).

Dash, P. & Punia, M. Governance and disaster: analysis of land use policy with reference to Uttarakhand flood 2013, India. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 36, 101090 (2019).

Wilshusen, P. R., Brechin, S. R., Fortwangler, C. L. & West, P. C. Reinventing a square wheel: critique of a resurgent ‘protection paradigm’ in international biodiversity conservation. Soc. Natur. Resour. 15, 17–40 (2002).

Yu, P., Xu, R., Abramson, M. J., Li, S. & Guo, Y. Bushfires in Australia: a serious health emergency under climate change. Lancet Planet. Health 4, e7–e8 (2020).

Hunt, K. M. R. & Menon, A. The 2018 Kerala floods: a climate change perspective. Clim. Dynam. 54, 2433–2446 (2020).

Ahmadi, M. S., Sušnik, J., Veerbeek, W. & Zevenbergen, C. Towards a global day zero? Assessment of current and future water supply and demand in 12 rapidly developing megacities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 61, 102295 (2020).

Padma, T. V. Mining and dams exacerbated devastating Kerala floods. Nature 561, 13–14 (2018).

Joseph, J. K. et al. Community resilience mechanism in an unexpected extreme weather event: an analysis of the Kerala floods of 2018, India. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 49, 101741 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all participants of the Innovative Session: ‘Helping or hindering? The political effects of ‘emergency’ frames in environmental governance’, held at the 2020 Virtual Forum on Earth System Governance. J.P. received funding from the European Research Council as principal investigator of the project BACKLASH (grant agreement number 949332). C.W. received funding from the Australian Research Council as principal investigator of the project Foresight in Times of Disruption (grant agreement noumber DE200100922). L.W. received funding from the European Research Council as a member of the project LO-ACT (grant agreement number 804051).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (J.P., C.W., L.W., M.C.B., M.M. and D.J.) contributed to conception and design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Sustainability thanks Edward Maibach and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–4 and Figs. 1–3.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patterson, J., Wyborn, C., Westman, L. et al. The political effects of emergency frames in sustainability. Nat Sustain 4, 841–850 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00749-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00749-9

This article is cited by

-

Political economy of just urban transition

Nature Climate Change (2024)

-

Assumptions and contradictions shape public engagement on climate change

Nature Climate Change (2024)

-

A watershed moment for healthy watersheds

Nature Sustainability (2023)

-

Climax thinking on the coast: a focus group priming experiment with coastal property owners about climate adaptation

Environmental Management (2022)

-

Compound urban crises

Ambio (2022)