Abstract

Using data from social security records and an event study approach, we estimate the child penalty in Spain, looking at disparities for women and men across different labor outcomes following the birth of the first child. Our findings show that, the year after the first child is born, mothers’ annual earnings drop by 11% while men’s remain unchanged. The gender gap is even larger 10 years after birth. Our estimate of the long-run child penalty in earnings equals 28%, similar to those found for Denmark, Finland, Sweden or the USA. In addition, we identify channels that may drive this phenomenon, including reductions in working days and shifts to part-time or fixed-term contracts. Finally, we provide evidence of heterogeneous responses in earnings and labor market participation by educational level: college-educated women react to motherhood more on the intensive margin (working part-time), while non-college-educated women are relatively more likely to do so in the extensive margin (working fewer days).

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The significant wage gap between male and female workers remains, to date, an undeniable reality in all countries. For instance, women’s median gross salary in Spain represented 78.6% of that of men’s in 2018.Footnote 1 The literature has discussed several explanations for this gap, including the role of human capital and career choices (Bertrand 2011; Blau and Kahn 2017; Buser et al. 2014; Olivetti and Petrongolo 2016), gender-based discrimination (Goldin and Rouse 2000), as well as the role of child-rearing responsibilities.

Related to the last explanation, a recent study by Kleven et al. (2019a) concludes that most of the gender wage gap is linked to the effects of maternity. In their analysis, they use Danish administrative data to perform an event study around the birth of the first child. Intuitively, this empirical approach compares how earnings evolve in the years before and after giving birth, while flexibly accounting for age, as well as year and month effects. They find evidence of a large and persistent impact of having children on various labor market outcomes.Footnote 2 Specifically, they find a female child penalty in earnings of 30% in the first year after the first childbirth, which converges to about 20% in the long run.Footnote 3 By contrast, men’s earnings do not change in the event of having children. Moreover, Kleven et al. (2019a) provide evidence that women’s labor force participation, hours of work, and wage rate fall after the first childbirth, while this is not the case for men. Lastly, they conduct a decomposition analysis and find a striking increase in the fraction of child-related gender inequality from 40% in 1980 to about 80% in 2013.

In this paper, we provide evidence from Spain using longitudinal data from Social Security records. Our contribution is twofold. First, we fill an existing gap in the literature by estimating the child penalty in Spain. Second, our dataset allows us to provide novel evidence regarding effects by contract characteristics. Specifically, we can test how parenthood affects men’s and women’s probability of working part-time (versus full-time) and in temporary (versus permanent) jobs.

To estimate the effects of parenthood on women’s and men’s labor earnings, we follow closely the approach proposed by Kleven et al. (2019a). We find that female and male employees follow a similar trend until the birth of their first child. However, at the time of the birth event, their earnings progression abruptly diverge. Our findings suggest that the short-run child penalty, defined as the amount by which women fall behind men due to motherhood in the first year, equals 11.4%. This phenomenon is amplified in the long run, with the child penalty widening to 28% after ten years. Our results point to a gender gap that is in line with that found for Denmark, although with higher persistence in the case of Spain.

Next, we provide some additional results to shed some light on the drivers of this gap. First, there are similar child penalties (10% in the short-run and 23% after 10 years) on the number of days worked—women reduce considerably their working days after their first childbirth, while men’s do not change. Second, women become more likely to work part-time right after having the first child, while that probability barely changes for men. Third, women’s likelihood of working on a fixed-term contract increases steadily over time while, again, men’s do not change. Fourth, we provide results by the educational level of parents, showing that (i) the drops in earnings and days of work are substantially larger for non-college-educated than for college-educated women, (ii) the increase in women’s part-time work, by contrast, is larger for college than for non-college women, and (iii) the increase in fixed-term works is larger for non-college-educated women. Overall, our analysis of the mechanisms highlights the presence of substantial heterogeneity by educational level, suggesting that college-educated women react to motherhood more on the intensive margin (working part-time), while non-college-educated women are relatively more likely to do so in the extensive margin (working fewer days).

Finally, we put our findings from Spain in relation to those from other countries. Kleven et al. (2019b) extend the Denmark analysis from Kleven et al. (2019a) to five additional countries: the United Kingdom, the USA, Germany, Austria, and Sweden. On the one hand, the study confirms the existence of child penalties for all these countries; on the other, it finds important differences in the magnitude of motherhood effects on earnings. Even though Sweden features similar long-run penalties to Denmark (26%), in the short-run the child penalty in Sweden exceeds 60%, twice the rate for Denmark. Both the USA and the UK perform similarly, featuring penalties of almost 40% in the first year after childbirth that evolve to 31 and 44% after ten years. The most extreme cases are Austria and Germany, which feature short-run penalties of almost 80% and long-run penalties of 51 and 61%, respectively. Besides, Sieppi and Pehkonen (2019) complement the previous evidence by calculating the child penalty in Finland with similar results to those found for the other two Nordic countries: 61% in the short run and 25% in the long run.Footnote 4 Our estimate of the long-run earnings child penalty is similar in magnitude to that found for Sweden and the USA, and lower than that found in the UK, Austria, and Germany.Footnote 5

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the institutional framework, the data and the econometric specification of our analysis. Section 3 presents the results. Section 4 concludes. Supplementary information is available in the “Appendix”.

2 Institutional framework, data and empirical design

2.1 Institutional framework

In recent decades, the Spanish labor market has been characterized by the coexistence of fixed-term contacts with low firing costs and highly protected open-ended contracts, a rigid collective bargaining system and, above all, extraordinarily high fluctuations in the unemployment rate.Footnote 6 From a gender perspective, the unemployment rate has always been greater for women than for men: after 2008, the gap narrowed considerably until its virtual convergence in 2012, but then started widening again reaching more than 3% points in 2018. Temporary employment is also more common among young workers and women. Furthermore, since the late 1970s, women’s labor force participation in Spain has followed a persistent upward trend while men’s labor force participation has declined (see Fig. 1). As a result, the gender gap in labor force participation narrowed markedly from 49 to 11.5% points between 1980 and 2018. This is true for most OECD economies, but Spain experienced one of the strongest convergence processes in this period because of its extremely low female labor participation rates in the 1970s.

Although fertility has declined across OECD countries during the last four decades, Spain has experienced the sharpest changes. The Spanish total fertility rate has declined from 2.2 children per woman in 1980 to 1.3 in 2018 (see Fig. 2). Several competing forces are responsible for this demographic transformation, such as job insecurity, long periods of high and persistent unemployment, women’s increasing enrollment in college-degree education, and other cultural and institutional factors (De la Rica and Iza 2005; Adserà 2011; Guner et al. 2019; Lopes 2020; Bover et al. 2021).

Regarding family policies, the maternity leave as a family right was established in 1980. That year, mothers were entitled to six weeks of compulsory, fully compensated maternity leave, while fathers were granted two days of paid job absence. In 1989, the mother’s right was acknowledged to assign part of her maternity leave to the father. In 1999, families were granted additional ten weeks of full pay parental leave that were interchangeable between mother and father.After the paid leave period, either parent could take unpaid leave for up to 3 years, with the right to return to the same job, and reduce working hours by up to 50%, as well as the proportional pay, until the child turned 6.

The right to reduce working hours was lengthened twice: first, until the child turned 8 in 2007, and then 12 in 2012. However, in practice, very few fathers took paternity leave, made use of the unpaid leave, or reduced their working hours (Fernández-Kranz and Rodríguez-Planas, 2020). This left most of the burden of childcare and housework to women, who cut back on employment outcomes (Farré and Libertad 2018). The paid and non-transferable paternity leave was instituted in 2007 (see Fig. 3). For the first time, fathers were granted 13 days of leave at full pay, which could be taken at the same time or immediately after the maternity leave period. From then on, Spain has extended the paternity leave to four weeks in 2017, five weeks in 2018, eight weeks in 2019, twelve weeks in 2020,Footnote 7 and sixteen weeks in 2021, finally catching up with the duration of the maternity leave.Footnote 8

2.2 Data

We use administrative records from the Continuous Sample of Working Histories (in Spanish, Muestra Continua de Vidas Laborales, MCVL), a 4% random sample of all affiliates to the Social Security in each reference year. Information from those individuals is merged with richer data from the municipal census and the tax administration. From 2005 to 2018, the MCVL has a proper longitudinal design, following the same individuals over time as long as they keep registered to the Social Security at least for one day in the year either as active affiliate or pensioner. In addition to those individuals who were present in the previous wave, the sample is refreshed each wave with new members to ensure that the sample remains representative of the population of reference. Moreover, the MCVL includes historical labor market information dating as far back as 1967, with some earnings data being available since 1980, allowing us to construct the individuals’ employment history on a monthly basis. Also, whenever a member stops working for a number of months but re-enters later, we identify that spell as a career break and assign the value zero to earnings. Only those individuals who die, leave definitively the country, or stop working completely and who never come back afterward as pensioners are no longer listed as Social Security affiliates in further MCVL waves.

The estimation sample we use covers workers registered in the Social Security system under the general regime. Information on contribution bases for the remaining schemes (mainly self-employment) has poor quality.Footnote 9 Besides, the exact family relationship of the employees to the individuals with whom they live is not made explicit in the dataset, thus implying that some assumptions are required to identify their children. In this respect, we infer that a worker’s first child has been born when we observe an individual of age 0 to 1 living together with an adult worker, as long as the adult individual is between 18 and 45 years old at the birth momentFootnote 10, and no other child is present in the same household at that time.

Following Kleven et al. (2019a), we track the same workers from up to five years before to up to ten years after the birth of their first child. In our setup, a balanced panel like this implies that individuals remain listed in the Social Security system for the whole period.Footnote 11 In contrast, “unbalanced” encompasses all individuals affiliated at any point in time with no specific duration. Although the balanced sample ensures comparability across individuals over time, given that we will track each individual’s labor market history for at least 15 years, this restriction also imposes some selection in terms of using information from individuals that managed to remain attached to the Spanish labor market for a long period of time.

Additionally to demographic characteristics of the individuals, the labor market side is well represented in the data with income records from two different sources—monthly contribution bases and taxable income information—job-specific variables, and the number of days worked per year.Footnote 12 Regarding the measurement of labor earnings, our preferred option is to use monthly contribution bases, for which comprehensive historical data are available since the late 1990s. Earnings from contribution bases are, however, top-coded due to regulatory constraints.Footnote 13 An alternative approach would be to use annual, unbounded labor income from tax records, yet the data start in 2005. Figure 6 in the “Appendix” shows average earnings profiles over time, comparing the different possible samples and income sources.Footnote 14 The main takeaways from this figure are: (i) for women, we observe a decrease in earnings after the birth of the first child, a feature not seen in men (ii) differences in earnings profiles between balanced and unbalanced samples are more pronounced starting in 2005 than in 1990 because of the huge impact that the Great Recession had on employment,Footnote 15 and (iii) the incidence of censorship for women is very small (note that the gray and brown lines overlap).

Our estimation sample covers 543,828 employees (264,391 mothers and 279,437 fathers) and almost 95 million monthly observations from 1990 to 2018. Table 1 shows the summary statistics. First, average monthly wages are higher for men than for women (1,893 vs. 1,281 euros, respectively), and for college-educated in relation to non-college-educated individuals. In terms of days worked in a month, men spend on average five days more at work than women; within the latter, college-educated women work substantially more days than non-college women. Also, part-time work occurs more frequently for women (4% for men vs. 23% for women), a feature also observed for fixed-term contracts though to a lesser extent. Finally, women are more likely than men to hold college education (63% vs. 53%, respectively).

2.3 Empirical design

We follow the event study specification proposed by Kleven et al. (2019a). This setup is based on comparing mothers’ labor market outcomes relative to fathers’ around the event of the first childbirth. The baseline specification stems from a balanced panel in which we observe each parent from five years before to ten years after their first child is born. Therefore, the event time t is indexed in relation to the year of the first childbirth, in a way such that \(t=0\) for the first year after the birthdate, with t ranging from -5 to +10.Footnote 16

In particular, we run the following regression separately for men and women:

where \(Y_{ist}^{g}\) represents the outcome of interest for individual i of gender g at calendar time s at event time t. Each individual i contributes with one observation per year t, referenced to the month of birth. The right-hand side of the specification includes age, calendar time (year \(\times \) month) interactions, and event time binary variables. We exclude the event time dummy corresponding to \(t=-1\), so that the event time coefficients capture the impact of parenthood relative to the year preceding the first childbirth. Moreover, the inclusion of age dummies controls nonparametrically for latent life-cycle trends and, similarly, the year and month dummies control for business cycle effects.Footnote 17

Our main outcome \(Y_{ist}^{g}\) is gross annual earnings. We construct this variable using monthly observations in the following way: for each individual, we take as a reference the year and month of birth of the first child; for each year until/since that point, we take the contribution base for the reference month and add the preceding 11 monthly bases. Besides, we have also considered two other measures yielding similar estimation results; however, the chosen baseline minimizes the observed differences in earnings between men and women before childbirth.Footnote 18

The effects on earnings might arise from changes in the extensive margin (number of days worked), the intensive margin (number of hours worked per day), or from changes in the wage rate. Given that our data do not contain information on hours worked, we cannot estimate effects on the wage rate. However, we can gauge the relative changes in the extensive and intensive margins, by considering as alternative outcomes “number of days worked per year,” “part-time job,” and “fixed-term job.” Finally, for each of these outcomes, we perform a heterogeneity analysis by running the estimating equation separately for college-educated and non-college-educated workers.

In a second step, the estimated level effects are converted into percentage figures, calculated as

where \(\tilde{Y}_{ist}^{g}\) is the predicted labor income net of the event time dummies, that is, the counterfactual in the hypothetical case of not having children:

and \(E[\tilde{Y}_{ist}^{g}|t]\) is the mean of the predicted values at time event t.

Once the children effect has been estimated separately for men and women, we measure child penalty as the percentage by which women fall behind men due to children at event time t:

As in Kleven et al. (2019a), there are two steps in the estimation of the child penalty: first, estimating the effect of the first child separately for men and women, and then estimating the child penalty. The former requires a stronger identification assumption: that mothers (fathers) having first child in year t would have followed the same trends as mothers (fathers) having first child in another year had neither of them had children. Hence, the separate earnings dynamics for mothers and fathers should be interpreted with caution. The second step (the child penalty), by contrast, relies on the milder smoothness assumption of event studies. This assumption is validated with tests of parallel trends before childbirth, i.e., the wage (or other outcome) trajectories of men and women being parallel for \(t<0\). Even under parallel trends, two remarks are in order: first, this approach requires no anticipation, as women who anticipate that next-year’s earnings will decline might decide (to try) to become pregnant; second, the smoothness around the date of birth may be less informative as we consider periods further away from the event.Footnote 19 Finally, it is important to note that our results for part time, and fixed-term-contract results are conditional on working and thus include any selection effects into employment. If, as traditional selection models would predict, workers are positively selected on wage rates, then our estimates of the penalty for those two outcomes will be biased downwards (see Kleven et al. 2019a; Costa-Dias et al. 2020).

3 Results

3.1 Impacts of first child

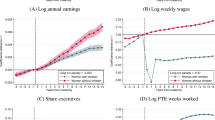

Graph (a) in Fig. 4 presents the gross annual earnings trajectory for men and women throughout a 15-year window around the birth of their first child. For that purpose, we plot the gender-specific estimates of total earnings before taxes and transfers, previously defined as \(P_{t}^{g}\), across event time. These outcome estimates at event time t are expressed relative to the year before the first childbirth, i.e., event time \(t-1\). Given that, like Kleven et al. (2019a), we focus on the first child, these estimates also include the penalties to subsequent births.

As can be seen in the graph, in the year following the birth of the first child, mothers face a loss in gross earnings of 11.2% with respect to their pre-birth rate, while fathers’ earnings increase by 0.15%. During the following year, women’s earnings continue declining to 19.5%. This diverging trend in earnings for male and female workers continues even ten years after the first childbirth, so that throughout the years, women’s earnings never return to levels prior to maternity. In fact, ten years after the birth of a first child, female earnings stabilize at around 33% lower, whereas male earnings drop by 5%. Hence, our estimate of the long-run child penalty is 28% points. These estimates resulting from the baseline specification confirm a significant and persistent negative effect for mothers in a ten-year bracket; moreover, the divergence remains when extending the analysis to 15 years ahead (see Fig. 8 in the “Appendix”).Footnote 20

Impacts of first child. Notes: The figure shows event time coefficients estimated from Eq. (2), absent children for men and women separately and for different outcomes. Each graph also reports a long-run child penalty—the percentage by which women are falling behind men due to children, calculated from equation (3) at event time \(t=10\). All of these statistics are estimated on a balanced sample of parents who have their first child between 1994 and 2009 and who are observed in the data during the entire period between five years before and ten years after child birth. The effects on earnings and days of work are estimated unconditional on employment status, while the effects on part time and fixed-term contract are estimated conditional on working

Next, we study some possible mechanisms underlying this gender gap. Graph (b) in Fig. 4 shows that, even when men and women are on similar trends in terms of their number of days worked in a year prior to becoming parents, women’s days worked fall significantly after childbirth, albeit men’s do not change. In particular, our estimates reveal that, 10 years after childbirth, women reduce the number of days worked by 26%, while the change for men is negligible. Moreover, graph (c) also shows large gender differences in the probability of working part-time. While men’s part-time probability decreases after parenthood, such probability increases considerably for women (indeed, the relative gap equals 43% after 10 years). Finally, graph (d) shows that women become more likely (29%) to work under a fixed-term contract after childbirth, while men’s probability becomes 6% lower.Footnote 21

Alternatively, we consider two additional mechanisms complementing our sample with information coming from a special module of the Spanish labor force survey in 2010. First, we merge both datasets using the economic activity of the firm (by means of the National Classification of Activities 2009 at two digits). Next, we define (i) long-hours sectors as those above the median in the proportion of workers working 40 (or, alternatively, 50) hours per week; and (ii) flexible sectors as those above the median in the proportion of workers who can adjust working time or can take days off due to family reasons. We measure the impact of the first child on the likelihood of working in such sectors (see Fig. 9 in the Appendix). We find, first, that women’s probability to work in long-hours sectors declines in the very first year after childbirth and reaches pre-birth values approximately six to ten years after. On the contrary, men show a continuous upward trend throughout the years, so that men’s probability to work in long-hours sectors is always above that of women.Footnote 22 Second, we estimate a higher probability for women to work in sectors allowing for flexible working hours or taking days off due to family reasons, while men’s probability barely changes. In both cases, the relative gap narrows rapidly and, for sectors granting days off due to family reasons, even disappears after three years.Footnote 23

3.2 Impacts of first child by education

As noted by Kleven, Landais, and Søgaard (2020a), if there is heterogeneity in child penalties by education, this might be suggestive that a comparative advantage channel is driving (part of) the child penalty. To check whether women at the top of the education distribution incur the same penalty as women at the bottom, in Fig. 5 we perform the same analysis as in Fig. 4, but we condition on the educational level. We define education as the the maximum level reached pre-birth so that education cannot be a bad control (i.e., an outcome).

Graphs (a) and (b) show that the drops in earnings and days of work are significantly larger for non-college-educated than for college-educated women.Footnote 24 Graph (c) reveals that right after the birth the increase in women’s part-time work, by contrast, is larger for college than for non-college women (although the impacts tend to converge over time). Finally, the increase in fixed-term contracts is larger for non-college-educated women than for college-educated women. In this case, however, we also see some differences for men, with college-educated men also becoming significantly less likely to work on a fixed-term job over time once they become parents, while for non-college men that probability barely changes.

Impacts of first child, by education. Notes: Same data and estimating equation as in Fig. 4, conditioning on the educational level

Our results in this respect are not completely aligned with those in Kleven, Landais, and Søgaard (2020a), who show that there is essentially no heterogeneity in child penalties with respect to the relative education levels of the parents. The heterogeneity patterns we uncover for the Spanish case could be due to the comparative advantage channel, as proposed by the literature.Footnote 25

3.3 Comparison to other countries

Table 2 compares the long-run penalties in Spain with those found in other countries. For comparability purposes, the Spanish estimate has been recalculated as the average for event times five to ten (note that the penalty at \(t=10\) equals 28.2). The table also compares age at first birth and total number of children. The magnitude of the Spanish child penalty lies between those found for some Nordic countries—higher than Denmark and Finland, which present the lowest rates, though lower than Sweden—and the estimate for the USA. On the contrary, the German-speaking countries (Germany, Austria) feature the highest motherhood penalties, with the UK below. Although Spain has not achieved the degree of gender equality that characterizes Nordic countries,Footnote 26 Spain’s values have converged in recent years.Footnote 27 Nevertheless, Spain has the highest parent’s age at the first childbirth event and the lowest number of children among the countries considered in the comparison.

4 Concluding remarks

Motherhood explains a significant proportion of the gender gap in earnings. Using longitudinal data from the Social Security records, we follow the event study methodology proposed by Kleven et al. (2019a) to estimate the child penalty in Spain. We explore the profiles over time of different labor market outcomes for men and women. In general, there are no remarkable differences until the first childbirth but women diverge considerably from that moment on. Our findings suggest that the child penalty in earnings is 11.4% in the year after the first child is born and continues widening to 28% in the long run. Overall, the magnitude of the Spanish child penalty is between those found for Nordic countries and Anglo-saxon countries.

Moreover, we document a variety channels through which mothers present a lower earnings profile. For instance, women reduce considerably their working time after their first childbirth, with a 15% child penalty in the number of days worked in the first year and 26% 10 years after. In terms of alternative work arrangements, the probability of women working part-time rises by 38% one year after their first child, while for men that probability decreases by 15%. Besides, women become increasingly more likely to work under a fixed-term contract while for men that probability decreases by 6%. We also find that reductions in earnings and days worked after the first childbirth are substantially larger for women with no college degree. In contrast, college-graduated mothers appear more prone to remain employed but working part-time.

Notes

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE), Encuesta Anual de Estructura Salarial (2018).

Before them, several studies aimed at quantifying the importance of motherhood for explaining the gender wage gap using different methodologies and obtaining similar results. Adda et al. (2017) develop a dynamic life-cycle model of the interaction between fertility, career and labor supply choices. Bertrand (2013) compares well-being measures among college-educated women with career and/or family, and measures the impact of motherhood on earnings. Fernández-Kranz et al. (2013) use Spanish Social Security records to investigate the underlying mechanisms that drive mothers’ lower earnings track, such as part-time work, accumulation of lower experience, or transitioning to lower-paying jobs. Angelov et al. (2016) use an alternative approach focusing on the within-couple earnings gap. They find that 15 years after the first child has been born, the male-female gender gaps in income and wages increase by 32 and 10% points, respectively. Lundborg et al. (2017) introduce a strategy based on in vitro fertilization and find that fertility has negative, large, and long-term effects on earnings. See also recent work by Andresen et al. (2019), Kleven et al. (2019a), and Pora and Wilner (2019) looking into the drivers of the penalty and potential reforms to address it.

Following the previous literature, throughout the document we refer to the short-run effect as the impact in the first year after the first childbirth, while the long-run effect refers to the impact 10 years after the first childbirth.

Note that Kleven et al. (2019b) and Sieppi and Pehkonen (2019) estimate the long-run effect as the average penalty five to ten years after the first childbirth. Berniell et al. (2020) estimate child penalties on the probability of working and other alternative modes of employment, such as part-time and self-employment, using retrospective data drawn from SHARE for 29 European countries.

The literature on child penalties has focused on the European and American cases but remains sparse for developing countries with different institutional settings and cultural norms. Berniell et al. (2018) show that, after the first childbirth, women’s gross earnings in Chile drop by 20 to 30%, and that this effect remains relatively stable in the long run. In a similar fashion, Querejeta (2020) studies the case of Uruguay and finds that formal employment falls by 30% in the short run; moreover, this penalty does not revert in the medium and long term, reaching 60% after ten years.

Unless stated otherwise, the statistics quoted in this section are taken from the Spanish Labor Force Survey (Encuesta de Población Activa) compiled by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

In 2020, fathers were forced to take leave the first four weeks after the childbirth, coinciding with the maternity leave, and the remaining eight weeks could be taken anytime within the first year. This enforcement was extended to six weeks in 2021.

Although further analysis for the Spanish case is needed, Kleven et al. (2020a, 2020b) examine family policy reforms in Austria and show that the expansion of parental leave and child care subsidies have no impact on gender inequality. In addition, Berniell et al. (2020) explore correlations between the maximum weeks of job-protected leave available to mothers, regardless of income, and the motherhood effects on employment finding a non-monotonic relationship between the duration of parental leave and female outcomes: while motherhood effects decrease with the length of job-protected maternity leave, there is a threshold beyond which that protection is ineffective.

In Spain, more than 80% of workers are enrolled in the general scheme of the social security system. There are alternative schemes for self-employed, workers in fishing, mining and agricultural activities, and domestic staff. For instance, as self-employed individuals choose how much to contribute themselves, García-Miralles et al. (2019) argue that income for self-employed can be poorly approximated using administrative data on tax returns. While this is a potential limitation of our analysis, we believe it may not have a big impact in practice. First, there are very few self-employed women (around 8% in our sample). Second, we do not observe a big change in the probability of being self-employed after childbirth.

We impose this age range to capture the parent-child relationship.

This does not imply that they appear as working employees for the whole period. They could have been not employed in between, even for long periods of time, as long as they have returned to work sometime after. They will be excluded from the balanced panel only in case of leaving the country, death, or having definitively left the labor market within those 15 years.

The MCVL does not include information on hours worked.

There is a legal upper bound on monthly contributions which, for the case of high-earners, makes a fraction of income unobservable.

Specifically, the figure shows results for unbalanced (“U.” lines) or balanced samples (“B.” lines); and for using contribution bases (“bases” lines) or uncapped taxable income (“tax-in.” lines) as income measures. For the contribution bases, we show results for samples starting in years 1990 and 2005.

In any case, we repeated our estimation in an unbalanced sample obtaining robust estimates for the long-run child penalty (see Fig. 7 in the “Appendix”).

Similarly, we extend our analysis to further capture very long-run effects by using observations up to 15 years after the first birth event.

Unlike Kleven et al. (2019a), we are able to pin down the month of birth of the first child.

Firstly, for each individual and year from / to the birth of the child we add the 12 monthly observations in that year (event year measure). Second, for each individual and natural year we add the 12 corresponding monthly observations and then compute the average over the time event variable (natural year measure).

The effects on labor market outcomes can also be determined by decisions anticipating fertility. For instance, women with a strong preference for children may invest less in education or work experience in anticipation of motherhood, which would lead to lower earnings. Our estimation approach does not capture such ex ante effects, but their relevance depends on how far earlier the labor market outcomes are measured with respect to the childbirth (Alba et al. 2009). Moreover, Adda et al. (2017) argue that occupational choices due to anticipated fertility represent a very small fraction of the total earnings loss from children.

Estimates of the child penalty in the year following the child birth using the alternative definition of annual earnings are 15.2 and 12.5 for the event year and the natural year measures, respectively, relative to the 11.4 in the baseline specification; whereas the estimates in the long run are 26.7 and 26.1, respectively, relative to the 28.2 in the baseline.

Collischon et al. (2020) study the impact of a German subsidy program (“Minijobs”) that allows women to reduce their working hours after childbirth. They find that the child penalty in earnings for women entering in “Minijobs” after birth was larger and more persistent eight years after compared to mothers who directly return to regular employment.

The relative gender gap equals 0.11 (0.10) after 10 years in sectors with a proportion of workers working 50 (40) hours per week above the median

In this vein, Bütikofer et al. (2018) exploit Norwegian administrative data to estimate the earnings penalty due to parenthood among different high-earnings careers. They find that women in occupations with nonlinear wage structures such as MBA and lawyers suffer from a larger and more persistent child earnings penalty in contrast to women in occupations characterized by more linear wage structures such as STEM occupations. In our data, however, the long-run child penalty for those who were working in long-hours sectors at time event -1 is lower than the child penalty estimated for the whole sample (12.5 versus 28.2). Indeed, among those who always remain in long-hours sectors after the child birth, the long-run child penalty is 2.6%.

Repeating the exercise in the unbalanced sample for college graduates starting in 2005 and using the uncapped taxable income as earnings measure, yield very similar results (a long run child penalty of 24% instead of 25%), implying that the lower impact for this group is not due to the censoring of contribution bases (see Fig. 10 in the Appendix).

Alba and Álvarez (2004) conclude that college-educated women show greater attachment to the labor market than non-college-educated women. Moreover, women who were more frequently unemployed before the childbirth face higher volatility in the labor market after becoming mothers than those who were employed, which enjoy greater job stability after motherhood.

Nordic countries were some of the earliest to adopt effective social policies in terms of gender equality. Thus, they have one of the most gender-equal labor markets in the OECD, along with small gender gaps in labor market participation, employment, and working hours.

For example, we have considered question R3 (“Do you think that women should work full-time, part-time, or not at all under certain circumstances...?”) from the ISSP (International Social Survey Programme) 2012 dataset and built an indicator of the share of people who answer Stay at home. This indicator takes values of 5.2% in Denmark, 10.5% in Sweden, 24.4% in Spain, 27.9% in the USA, 33.7% in the United Kingdom, 49.3% in Austria but 19.7% in Germany. If we plot this indicator against the long-run penalties in earnings, we obtain that the higher the share of those for whom women should stay at home, the higher the penalty. However, this correlation is obtained from just seven observations; hence, it would be at most suggestive.

References

Adda J, Dustmann C, Stevens K (2017) The career costs of children. Journal of Political Economy 125(2):293–337

Adserà A (2011) Where are the babies? Labor market conditions and fertility in Europe. European Journal of Population 27(1):1–32

Alba A, Álvarez G, Carrasco R (2009) On the estimation of the effect of labour participation on fertility. Spanish Economic Review 11(1):1–22

Alba A, Álvarez G (2004) La actividad laboral de la mujer en el entorno del nacimiento de un hijo. Investigaciones económicas 28(3):429–460

Angelov N, Johansson P, Lindahl E (2019) “What causes the child penalty and how can it be reduced? Evidence from same-sex couples and policy reforms”. Discussion Papers 902, Statistics Norway, Research Department

Angelov N, Johansson P, Lindahl E (2016) Parenthood and the gender gap in pay. Journal of Labor Economics 34(3):545–579

Berniell I, Berniell L, de la Mata D, Edo M, Marchionni M (2018) “Motherhood and the missing women in the labor market”. Working Papers 2018/13, Corporación Andina de Fomento

Berniell I, Berniell L, de la Mata D, Edo M, Fawaz Y, Machado Matilde P, Marchionni M (2020) “Motherhood, Labor Market Trajectories, and the Allocation of Talent: Harmonized Evidence on 29 Countries”. Documentos de Trabajo del CEDLAS N\(^{\underline{o}}\) 270, Noviembre, 2020, CEDLAS-Universidad Nacional de La Plata

Bertrand M (2011) “New Perspectives on Gender”. Handbook of Labor Economics, 4b., ed. O. Ashenfelter and D. Card, Chapter 17, 1543-1590. North Holland: Elsevier Science Publishers

Bertrand M (2013) Career, family, and the well-being of college-educated women. American Economic Review 103(3):244–50

Blau F, Kahn L (2017) The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations. Journal of Economic Literature 55(3):789–865

Bover O, Guner N, Kulikova Y, Ruggieri A, Sanz C (2021) “Family-Friendly Policies and Fertility: What Firms Got to Do With It?”, mimeo

Buser T, Niederle M, Oosterbeek H (2014) Gender, competitiveness, and career choices. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(3):1409–1447

Bütikofer A, Jensen S, Salvanes KG (2018) “The role of parenthood on the gender gap among top earners”. European Economic Review, 109(C): 103-123

Collischon M, Cygan-Rehm K, Riphahn RT (2020) “Long-run effects of wage subsidies on maternal labor market outcomes”, mimeo

Costa-Dias M, Joyce R, Parodi F (2020) The gender pay gap in the UK: children and experience in work. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 136(4):855–881

De la Rica S, Iza A (2005) Career Planning in Spain: Do Fixed-Term Contracts Delay Marriage and Parenthood? Review of the Economics of the Household 3(1):49–73

Farré L, González L (2018) “Does paternity leave reduce fertility?”. Journal of Public Economics, 172(C): 52-66

Fernandez-Kranz D, Lacuesta A, Rodriguez-Planas N (2013) The Motherhood Earnings Dip: Evidence from Administrative Records. Journal of Human Resources 48:169–197

Fernandez-Kranz D, Rodriguez-Planas N (2020) “Too family friendly? The consequences of parents’ right to request part-time work”. Journal of Public Economics, 197(2): 104-407

García-Miralles E, Guner N, Ramos R (2019) The Spanish personal income tax: facts and parametric estimates. SERIEs 10:439–477

Goldin C, Rouse C (2000) Orchestrating impartiality: The impact of blind auditions on female musicians. American Economic Review 90(4):715–741

Guner N, Kaya E, Sánchez-Marcos V (2019) “Labor Market Frictions and Lowest Low Fertility”. CEPR Discussion Papers 14139

Kleven H, Landais C, Søgaard JE (2019) Children and Gender Inequality: Evidence from Denmark. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11(4):181–209

Kleven H, Landais C, Posch J, Steinhauer A, Zweimüller J (2019) Child Penalties across Countries: Evidence and Explanations. AEA Papers and Proceedings 109:122–126

Kleven H, Landais C, Søgaard JE (2020a) “Does Biology Drive Child Penalties? Evidence from Biological and Adoptive Families”. American Economic Review: Insights, forthcoming

Kleven H, Landais C, Posch J, Steinhauer A, Zweimüller J (2020b) “Do Family Policies Reduce Gender Inequality? Evidence from 60 Years of Policy Experimentation”. NBER Working Paper w28082

Lopes M (2020) “Job Security and Fertility Decisions”. mimeo

Lundborg P, Plug E, Würtz Rasmussen A (2017) Can women have children and a career? IV evidence from IVF treatments. American Economic Review 107(6):1611–37

Olivetti C, Petrongolo B (2016) The Evolution of the Gender Gap in Industrialized Countries. Annual Review of Economics 8:405–434

Pora P, Wilner L (2019) “Child Penalties and Financial Incentives: Exploiting Variation along the Wage distribution”. Working Papers 2019-17, Center for Research in Economics and Statistics

Querejeta M (2020) “Impacto de la maternidad sobre el ingreso laboral en Uruguay”. Serie Estudios y Perspectivas, 47, CEPAL

Sieppi A, Pehkonen J (2019) “Parenthood and Gender Inequality: Population-based Evidence on the Child Penalty in Finland”. Economics Letters, 182(C): 5-9

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We are grateful for useful comments to the Editor, three anonymous referees, Olympia Bover, and Ernesto Villanueva, as well as conference participants at 2021 RES conference, and the 2021 SEHO meeting. All errors remain our own. The opinions and analyses are the responsibility of the authors and, therefore, do not necessarily coincide with those of the Banco de España or the Eurosystem.

Appendix

Appendix

Earnings profiles. Notes: The figure represents averages of annual earnings (in 2018 thousand euros), calculated separately for men (on the left) and women (on the right). Each sample consists of individuals having their first child at event time \(t = 0\). Solid lines represent averages obtained from balanced panels (B) starting in 1990 (black) or in 2005 (gray for contribution bases and brown for uncapped taxable income). Dashed lines represent averages obtained from unbalanced panels (U) starting in 1990 (black) or in 2005 (gray for contribution bases and brown for uncapped taxable income)

Impact of the first child on earnings, balanced vs. unbalanced samples. Notes: Same estimating equation as in graph (a) of Fig. 4 but in both a balanced and an unbalanced panel of 15 years

Impact of the first child on working in long hours and flexible sectors. Notes: The effects are estimated as the probability of working in long hours and flexible sectors conditional on being working. Long hours sectors refer to those above the median in the share of workers working more than 40 (or 50) hours per week. Flexible sectors refer to those above the median in the share of workers that are allowed to adjust working time or take leave due to family reasons

Impact of the first child on earnings, college. Notes: Same estimating equation as in graph (a) of Fig. 4 but in the unbalanced sample for college graduates starting in 2005 and using the uncapped taxable income as earnings measure

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Quinto, A., Hospido, L. & Sanz, C. The child penalty: evidence from Spain. SERIEs 12, 585–606 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-021-00241-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-021-00241-9