Abstract

Introduction

Fidaxomicin is as effective as vancomycin in treating Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) but more effective at preventing recurrence. However, because fidaxomicin is more costly than vancomycin, its overall value in managing CDI is not well understood. This study assessed the budget impact of introducing fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for the treatment of adults with CDI from a hospital perspective in the US.

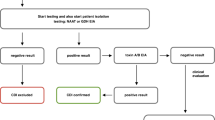

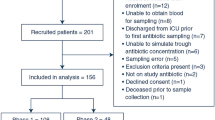

Methods

A cohort-based decision analytic model was developed over a 1-year horizon. A hospital with 10,000 annual hospitalizations was simulated. The model considered two adult populations: patients with no prior CDI episode and patients with one prior CDI episode. Two scenarios were assessed per population: 15% fidaxomicin/85% vancomycin use and 100% vancomycin use. Model inputs were obtained from published sources and expert opinion. Model outcomes included cost, payment, and revenue at the hospital level, per treated CDI patient, and per admitted patient. Budget impact was calculated as the difference in revenue between scenarios. One-way sensitivity analyses tested the effects of varying model inputs on the budget impact.

Results

In patients with no prior CDI episode, treatment with fidaxomicin resulted in potential savings over 1 year of $1105 at the hospital level, $14 per treated CDI patient, and $0.11 per admitted patient. In patients with one prior CDI episode, fidaxomicin use was associated with potential savings over 1 year of $1150 at the hospital level, $74 per treated CDI patient, and $0.12 per admitted patient. Savings were driven by a reduced rate of CDI recurrence with fidaxomicin treatment and uptake of fidaxomicin. Sensitivity analyses indicated savings when inputs were varied in most scenarios.

Conclusion

Budgetary savings can be achieved with fidaxomicin due to reduced CDI recurrence as a result of a superior sustained clinical response. Our results support considering the broader benefits of fidaxomicin, beyond its cost, when making formulary inclusion decisions.

Plain Language Summary

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is a common hospital-acquired infection that affects about half a million people in the US each year. In some patients who have already had CDI, it can recur. These recurrent infections can be difficult to treat, and they place a burden on the healthcare system. CDI is usually treated with the antibiotics fidaxomicin or vancomycin. Fidaxomicin is as effective as vancomycin for treating CDI but is even more effective than vancomycin at preventing CDI recurrence. However, fidaxomicin is more expensive. In this study, we estimated the impact of replacing vancomycin with fidaxomicin for treating CDI on the budget of a typical US hospital. We estimated that treating 15% of patients with CDI using fidaxomicin in place of vancomycin would save the hospital between $1105 and $1150 in a year. This means that despite the higher cost of fidaxomicin, treating as few as 15% of patients with CDI using fidaxomicin instead of vancomycin can be cost-saving for hospitals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

16 January 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-021-00583-8

References

Lessa FC, Gould CV, McDonald LC. Current status of Clostridium difficile infection epidemiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(Suppl 2):S65-70.

Reveles KR, Lee GC, Boyd NK, Frei CR. The rise in Clostridium difficile infection incidence among hospitalized adults in the United States: 2001–2010. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:1028–32.

McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:e1-48.

Barrett ML, Owens PL. Clostridium difficile hospitalizations, 2011–2015. U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2018. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/HCUPCDiffHosp2011-2015Rpt081618.pdf. Accessed 21 Sep 2020.

Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:825–34.

Aslam S, Hamill RJ, Musher DM. Treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated disease: old therapies and new strategies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:549–57.

Schroeder MS. Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:921–8.

Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431–55.

Khanna S, Gupta A, Baddour LM, Pardi DS. Epidemiology, outcomes, and predictors of mortality in hospitalized adults with Clostridium difficile infection. Intern Emerg Med. 2016;11:657–65.

Cornely OA, Miller MA, Louie TJ, Crook DW, Gorbach SL. Treatment of first recurrence of Clostridium difficile infection: fidaxomicin versus vancomycin. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(Suppl 2):S154–61.

Sheitoyan-Pesant C, Abou Chakra CN, Pepin J, Marcil-Heguy A, Nault V, Valiquette L. Clinical and healthcare burden of multiple recurrences of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:574–80.

McFarland LV. Alternative treatments for Clostridium difficile disease: what really works? J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:101–11.

Kuntz JL, Baker JM, Kipnis P, et al. Utilization of health services among adults with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a 12-year population-based study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38:45–52.

Ghantoji SS, Sail K, Lairson DR, DuPont HL, Garey KW. Economic healthcare costs of Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2010;74:309–18.

Zhang D, Prabhu VS, Marcella SW. Attributable healthcare resource utilization and costs for patients with primary and recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:1326–32.

Zhang S, Palazuelos-Munoz S, Balsells EM, Nair H, Chit A, Kyaw MH. Cost of hospital management of Clostridium difficile infection in United States-a meta-analysis and modelling study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:447.

Dificid (fidaxomicin), for oral use. Merck & Co., Inc.; 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/201699s011lbl.pdf. Accessed 21 Sep 2020.

Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM, et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:422–31.

Cornely OA, Crook DW, Esposito R, et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infection with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double-blind, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:281–9.

Bhatti T, Lum K, Holland S, Sassman S, Findlay D, Outterson K. A perspective on incentives for novel inpatient antibiotics: no one-size-fits-all. J Law Med Ethics. 2018;46:59–65.

Burton HE, Mitchell SA, Watt M. A systematic literature review of economic evaluations of antibiotic treatments for Clostridium difficile infection. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35:1123–40.

Foroutan N, Tarride J-E, Xie F, Levine M. A methodological review of national and transnational pharmaceutical budget impact analysis guidelines for new drug submissions. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;10:821–54.

Clancy CJ, Buehrle D, Vu M, Wagener MM, Nguyen MH. Impact of revised Infectious Diseases Society of America and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America clinical practice guidelines on the treatment of Clostridium difficile infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;72:1944–9.

Johnson S. Focused update on C. difficile infection treatment guidelines: fidaxomicin and bezlotoxumab. ID Week 2020 Virtual Meeting; 2020.

2018 annual report for the emerging infections program for Clostridioides difficile infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/eip/Annual-CDI-Report-2018.html. Accessed 13 Jan 2021.

Olsen MA, Yan Y, Reske KA, Zilberberg M, Dubberke ER. Impact of Clostridium difficile recurrence on hospital readmissions. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:318–22.

First DataBank AnalySource® Online. Wholesale acquisition cost (WAC). 2020. http://www.fdbhealth.com/fdb-medknowledge-drug-pricing. Accessed 21 Sep 2020.

FIRVANQ™ (vancomycin hydrochloride), for oral solution. CutisPharma; 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/208910s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 21 Sep 2020.

Rajasingham R, Enns EA, Khoruts A, Vaughn BP. Cost-effectiveness of treatment regimens for Clostridioides difficile infection: an evaluation of the 2018 Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70:754–62.

340B Health. Overview of the 340B drug pricing program. 2019. https://www.340bhealth.org/members/340b-program/overview/. Accessed 21 Sep 2020.

Zilberberg MD, Nathanson BH, Marcella S, Hawkshead JJ 3rd, Shorr AF. Hospital readmission with Clostridium difficile infection as a secondary diagnosis is associated with worsened outcomes and greater revenue loss relative to principal diagnosis: a retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12212.

HCUP: Healthcare Costs and Utilization Project. Overview of state inpatient databases (SID). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/sidoverview.jsp. Accessed 21 Sep 2020.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer price index. 2019. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/. Accessed 21 Sep 2020.

Feuerstadt P, Stong L, Dahdal DN, Sacks N, Lang K, Nelson WW. Healthcare resource utilization and direct medical costs associated with index and recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection: a real-world data analysis. J Med Econ. 2020;23:603–9.

Duhalde L, Lurienne L, Wingen-Heimann SM, Guillou L, Buffet R, Bandinelli PA. The economic burden of Clostridioides difficile infection in patients with hematological malignancies in the United States: a case-control study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41:813–9.

Gallagher JC, Reilly JP, Navalkele B, Downham G, Haynes K, Trivedi M. Clinical and economic benefits of fidaxomicin compared to vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:7007–10.

Watt M, McCrea C, Johal S, Posnett J, Nazir J. A cost-effectiveness and budget impact analysis of first-line fidaxomicin for patients with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in Germany. Infection. 2016;44:599–606.

Summers BB, Yates M, Cleveland KO, Gelfand MS, Usery J. Fidaxomicin compared with oral vancomycin for the treatment of severe Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a retrospective review. Hosp Pharm. 2020;55:268–72.

Lash DB, Mack A, Jolliff J, Plunkett J, Joson JL. Meds-to-beds: the impact of a bedside medication delivery program on 30-day readmissions. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2019;2:674–80.

Zillich AJ, Jaynes HA, Davis HB, et al. Evaluation of a “meds-to-beds” program on 30-day hospital readmissions. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020;3:577–85.

Cornely OA, Nathwani D, Ivanescu C, Odufowora-Sita O, Retsa P, Odeyemi IA. Clinical efficacy of fidaxomicin compared with vancomycin and metronidazole in Clostridium difficile infections: a meta-analysis and indirect treatment comparison. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:2892–900.

Okumura H, Ueyama M, Shoji S, English M. Cost-effectiveness analysis of fidaxomicin for the treatment of Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile infection in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2020;26:611–8.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and Rapid Service Fee were funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Medical writing, editorial, and other assistance

Medical writing assistance in the preparation of this article was provided by Julia Zolotarjova, MSc, MWC, and Phillip Leventhal, PhD, of Evidera. Support for this assistance was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Disclosures

Yiling Jiang is an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme (UK) Ltd., who may own stock and/or stock options in the company. Eric M Sarpong, Pamela Sears, and Engels N Obi are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA, who may own stock and/or stock options in the company.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Ethics committee approval was not required because this study was an economic simulation using data from previously conducted studies and did not involve any new studies of human subjects.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.

Prior presentation

The main findings of this study were presented as a poster at the Virtual International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) conference, May 18–20, 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original article was revised due to an error in copyright line.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, Y., Sarpong, E.M., Sears, P. et al. Budget Impact Analysis of Fidaxomicin Versus Vancomycin for the Treatment of Clostridioides difficile Infection in the United States. Infect Dis Ther 11, 111–126 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-021-00480-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-021-00480-0