Abstract

Deformed wing virus (DWV) has been linked to the global decline of honey bees. DWV exists as three master variants (DWV-A, DWV-B, and DWV-C), each with differing outcomes for the honey bee host. Research in the USA showed a shift from DWV-A to DWV-B between 2010 to 2016 in honey bee colonies. Likewise, in the UK, a small study in 2007 found only DWV-A, whereas in 2016, DWV-B was the most prevalent variant. This suggests a shift from DWV-A to DWV-B might have occurred in the UK between 2007 and 2016. To investigate this further, data from samples collected in 2009/10 (n = 46) were compared to existing data from 2016 (n = 42). These samples also allowed a comparison of DWV variants between Varroa-untreated (feral) and Varroa-treated (managed) colonies. The results revealed that, in the UK, DWV-A was far more prevalent in 2009/10 (87%) than in 2016 (43%). In contrast, DWV-B was less prevalent in 2009/10 (76%) than in 2016 (93%). Regardless if colonies had been treated for Varroa (managed) or not (feral), the same trend from DWV-A to DWV-B occurred. Overall, the results reveal a decrease in DWV-A and an increase in DWV-B in UK colonies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, honey bee colonies have been declining, with many reasons given, including pests and pathogens [1,2,3,4], pesticides [5, 6], habitat loss [7, 8], and the synergy between these factors [9]. Pathogens are identified as a major driver behind recent colony declines, in particular the association between the Varroa destructor mite (Varroa) and deformed wing virus (DWV) [10, 11]. DWV is a small (30 nm), single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus belonging to the family Iflaviridae within the order Picornavirales. DWV diversity is reduced in the initial presence of Varroa, and one dominant master variant is selected [10, 12]. Prior to the introduction of Varroa to colonies of A. mellifera, DWV is typically absent or at very low prevalence and load, but with high viral diversity [10]. High DWV loads have been detected in over 55% of all colonies or apiaries surveyed across 32 countries [13]. Symptomatic DWV manifests with dead pupae and deformed wings, discolouration, and bloated abdomens in adult bees. Asymptomatic infected bees may have a reduced lifespan [14, 15], impaired learning and memory [16], precocious behaviour [17], and perturbed immunity [12]. At the colony level, large numbers of mites and DWV lead to colony collapse [15].

The DWV complex is a quasispecies and as such is comprised of a diverse population of variants. Three closely related master variants have been identified so far: DWV-A [18], DWV-B (Varroa destructor virus 1) [19], and DWV-C [20]. DWV-A has been linked to colony losses [10, 21], whilst there is contention in the literature about the effects of DWV-B on colony health. In 2015, long-lived healthy Varroa-resistant colonies were found only to be infected with DWV-B [22]. This suggested that DWV-B may offer protection to colonies, via a phenomenon known as superinfection exclusion (SIE) [22], where DWV-B outcompetes the virulent DWV-A [10, 23, 24]. Furthermore, DWV-B is present in healthy colonies [23] and in those in which overwintering colony losses are low [21, 24]. In laboratory experiments, DWV-naïve honey bee pupae injected with DWV-A were less likely to survive when compared to larvae injected with DWV-B [25]. However, DWV-B has been shown to be lethal when experimentally injected into adult bees [26], and has also been attributed to the loss of workers during the overwintering period [27]. Notably, the colonies in this study [27] nonetheless survived the overwintering period and were still viable the following spring. It was also observed in cage experiments that DWV-B was equal to DWV-A at causing pupal death and wing deformities [28]. DWV-C is rare in both the UK and USA [21], whilst it has been detected in stingless bee colonies in Brazil [29] and was found to be the dominant variant in small hive beetle (Aethina tumida) samples from Hawaii [30], suggesting that DWV variants may have favored hosts.

The differing outcomes of colony health due to the prevalence and abundance (viral load) of different DWV master variants leads to a requirement for longitudinal studies that provide continual monitoring of DWV variants and honey bee pathogens, especially before and after the overwintering period. These types of studies will help to identify trends in colony loss and survival. To date, comparisons of master DWV variant and year have been made in the USA, with an increase in DWV-B prevalence from 2010 to 2016 [31]. However, DWV-A remained the dominant USA variant and was linked to colony loss [21]. Analysis of English honey bee samples collected in Devon in 2007 revealed that colonies were mostly dominated by DWV-A, and DWV-B was absent [32]. A longitudinal study of a subpopulation of these Devon bees revealed that an increase in viral load of DWV-A and C was correlated with overwinter colony losses [24, 32]. A country-wide survey of the UK in 2016 found no difference in DWV load between spring and autumn [21], and also that DWV-B was by far the most dominant and prevalent DWV master variant [21]. This suggests that a similar change may be occurring in the USA, as it has over the last ten years in the UK. Furthermore, in 2009, a total of 389 honey bee and 95 mite samples from 32 geographic regions across four continents were analyzed [11]. Of these, 246 (63%) tested positive for DWV, 205 of which (83%) were DWV-A and 41 (17%) were DWV-B. Interestingly, in 2009, all DWV-B samples were from Europe (France, n = 25; Germany, n = 13; Romania, n = 2; UK, n = 1) and were the same recombinant, composed of DWV-B Lp and Vp3 genes and DWV-A helicase and RdRP genes, and similar recombinants were also reported in the UK [33]. In France, a DWV-A/DWV-B recombinant with three breakpoints in the 5’ UTR, Vp3 and helicase gene was found [34], when previous studies had only detected variants with one or two breakpoints. A recent study of Apis mellifera and A. cerana in Asia also identified DWV-A and DWV-B recombinants in the 5’ UTR, Lp, Vp1, Vp2, alongside recombinants of DWV-A and an unknown variant in the Vpg and RdRp genes [35] (Supplementary Fig. S1B).

To investigate the possibility that a variant shift from DWV-A to DWV-B has occurred in the UK, we screened both managed (Varroa-treated) and feral (Varroa-untreated) honey bee colonies from 2009/10 and compared them to colonies analyzed in 2016 [24].

Materials and methods

Sample collection

All colony samples contained approximately 30 adult bees, for both 2009/10 and 2016 samples. A total of 16 feral colonies from 2009/10 were kindly donated to this study by Catherine Thompson [36]. The 30 managed, Varroa-treated 2009/10 colonies were provided by the National Bee Unit (NBU). The 2016 samples were collected in England and Wales by beekeepers as part of a larger study conducted in 2016 [21]. The distribution of samples and month collected for 2009/10 and 2016 are shown in Figure 1. All feral colonies were from wild, free-living bees that had a history of >1 year at the nest site, as reported by Thompson et al. [36] and the Welsh beekeepers that took part in the 2016 study [21].

Regional map showing sampling locations. The map shows the region and number of colonies sampled by year. The 2009/10 colonies are yellow, the 2016 colonies are blue, and feral colonies are marked with *. Four feral samples are not listed on the map, as their location was unknown. The table at the bottom shows the number of samples taken for each group by year and month.

Sample processing

A pool of 30 honey bees from each colony was homogenized using the mesh bag method [37] for samples collected in 2009/10, whilst a pool of 30 honey bees from 2016 was exposed to liquid nitrogen and homogenized using a mortar and pestle. RNA was extracted from a ~30-mg subsample from previously homogenized honeybees using an RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN), following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and were diluted to 50 ng/µl. We used the ABC assay [24], which reports on the conserved RdRp gene and represents the 3’ region of the DWV master genomes only. This assay cannot report on the prevalence of any DWV recombinant but rather provides an overview of whether there is a shift from DWV-A and its associated recombinants, and DWV-B and its associated recombinants, using a conserved region of the viral genome. Real-time PCR was performed using a Sensifast SYBR No-Rox One Step Kit (Bioline) with primers for DWV-A, DWV-B, DWV-C as described previously [24]. The RT-qPCR program is as follows: 45 °C for 10 min and 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 58.5 °C (DWV-A and DWV-B) or 61.5 °C (DWV-C) for 15 s, and 72 °C for 15 s. Each plate included an RNA standard curve and a no-template control. Actin controls were used to confirm the viability of the RNA from the NBU due to long-term storage of the samples. Melt curve analysis confirmed the absence of DWV in the no-template control and that one PCR product was amplified.

In addition to the ABC assay [24], a recombinant PCR assay [38] was performed on a subset of samples collected in 2016. Four combinations of DWV strain-specific primers (Supplementary Table S1) were used to amplify fragments >5 kb of DWV master variants and recombinants. Briefly, total RNA was used as a template to synthesise cDNA using an Invitrogen SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR reactions were prepared using a Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase Kit and 10 mM dNTPs obtained from New England Biolabs. Each reaction contained 5 µl of 5x Q5 buffer, 0.5 µl of 10 mM dNTPs, 0.25 µl of Q5 high-fidelity DNA polymerase, 1.25 µl of forward DWV-variant-specific capsid primer, 1.25 µl of reverse DWV-specific RdRp primer, 14.75 µl of nuclease-free water, and 2 µl of cDNA template. The thermocycler was set to initial activation at 98°C for 30 s, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 98°C for 10 s, annealing at 54°C for 20 s, and extension at 72°C for 3 min, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 2 min. Results were then visualised via gel electrophoresis using a 1.4% agarose gel containing gel red and a 1-kb hyper ladder.

Analysis of the results

The viral load is expressed as genome equivalents per honey bee, using the following equations [24]:

-

1)

Copy number RNA = (concentration RNA (ng/µL) × 6.022 × 1023)/(fragment length base pairs × 109 × 325)

-

2)

Genome equivalents = (average copy number generated by RT-qPCR) × (RNA dilution factor) × (elution volume of RNA) × (proportion of bee material*)

*Refers to the proportion of honey bee homogenate that was used to extract RNA (e.g., 30 mg homogenate / weight (mg) of a whole bee = the proportion of bee material).

The viral load of DWV variants was converted to a log10 value, and the total absence/presence and percentage of the DWV variant in each sample were determined. Any sample below 103 genome equivalents is too low to be reliably quantified, and samples with no amplification or melt curve were considered negative. Statistical analysis was conducted using non-parametric tests, as a Shapiro-Wilk test revealed that the viral load data were non-normally distributed. A Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the viral loads of each DWV variant. Comparisons of the 2009/10 and 2016 data sets were made for all the colonies and also between the feral (Varroa-untreated) and managed (Varroa-treated) colonies. Only DWV-A and DWV-B data were used for analysis, as DWV-C was rare. Post-hoc analysis was conducted using Dunn’s test of multiple pairwise comparisons [39]. The significance threshold was set at p < 0.05, and the significance levels were adjusted when multiple comparisons were made using Bonferroni correction (significance threshold/number of comparisons). A proportion Z test was used to calculate differences between percentage data.

Results

DWV prevalence and viral load for all colonies sampled in 2009/10 and 2016

A significant reduction in DWV-A-infected colonies occurred from 2009/10 (87%, n = 46) to 2016 (43%, n = 42; Z score, 4.3595, p < 0.0001; Fig. 2A), whereas the prevalence of DWV-B-infected colonies increased significantly from 76% to 93% between the years 2009/10 and 2016 (Z score, -2.1483, p = 0.03; Fig. 2A). During the study, there was no significant difference in DWV-A or DWV-B viral load from 2009/10 to 2016. Significant differences occurred when comparing DWV-A to DWV-B for each year, as DWV-B was always present at higher viral loads than DWV-A (Dunn’s test; 2009/10, p < 0.001; 2016, p < 0.00001; Fig. 2B). A small subset of samples from 2016 were analysed for DWV recombinants (Supplementary data). DWV recombinants did not dominate the 2016 dataset and were often detected in the presence of a master variant (Supplementary Fig. S1 [38]).

DWV prevalence and viral load in 2009/10 and 2016. (A) percentages of DWV-A- and DWV-B-positive colonies for the years 2009/10 and 2016. p-values were calculated using a proportional Z test. (B) Boxplots showing the DWV-A and B viral load of positive colonies for sample years 2009/10 and 2016. p-values were calculated using the Kruskal Wallis test and Dunn’s post-hoc test.

Regional DWV variant composition of managed colonies screened in 2009/10 and 2016

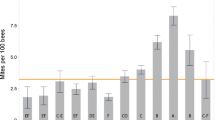

Individual analysis of each managed honey bee colony screened, per region, revealed that whilst DWV-B was the dominant variant for both years, DWV-A was far more prevalent in 2009/10 than in 2016 (Fig. 3A). A total of eight colonies were dominated by DWV-A in 2009/10, compared to only one colony in 2016 (Fig. 3A). The proportion of DWV-A in the 2016 colonies was less than 1% for six colonies and therefore cannot be visualised on the histogram (Fig. 3A), while the prevalence was 7% for one colony and >10% for three colonies (Fig. 3A). When comparing mean DWV loads in each region, DWV-A was >tenfold higher in samples collected in 2009/10 than in 2016 in all regions, whilst the DWV-B viral load increased >tenfold between 2009/10 and 2016 everywhere except in the South of England (Fig. 3B).

DWV composition in colonies. (A) location and proportional DWV composition (DWV-A, red; DWV-B, blue; not detected (N.D.), black) for each managed (Varroa treated) colony in 2009/10 and 2016. (B) The mean DWV-A and DWV-B viral load (log10), per region for all of the managed (Varroa-treated) colonies sampled in 2009/10 and 2016. Error bars show the standard error of the mean.

DWV variant load and prevalence in feral and Varroa-treated (managed) colonies from 2009/10 to 2016

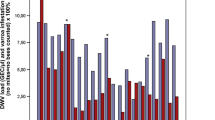

The same pattern of DWV-A prevalence was observed in both Varroa-treated (managed) and feral colonies, as DWV-A prevalence decreased from 2009/10 to 2016 (Fig. 4). Interestingly, almost 87% and 88% of managed and feral colonies, respectively, were DWV-A positive in 2009/10, whilst this was reduced by half in 2016 (Fig. 4). The opposite trend was seen in both managed and feral colonies for DWV-B. In 2009/10, 73% and 81% of managed and feral colonies were DWV-B positive, respectively. This increased to 90% in managed colonies and 100% in feral colonies in 2016 (Fig. 4). The DWV viral load between years remained consistent regardless of management or year (Fig. 5). However, 2009/10 feral colonies had a significantly higher DWV-A load than the 2009/10 managed colonies (Dunn’s test; p < 0.0001; managed, 1 × 105 – 1 × 108; feral, 1 × 108 – 1 ×1011; Fig. 5).

DWV load in feral versus treated colonies. A comparison of DWV-A and DWV-B viral loads (log10 DWV genome equivalents per bee) in feral and treated colonies from 2009/10 and 2016 is shown. Statistical comparisons were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn’s post-hoc test using Bonferroni correction. The samples sizes (n) are also given.

Discussion

In this study, we detected a DWV master variant shift from DWV-A to DWV-B between 2009/10 and 2016, occurring over a similar period to that in the USA [31]. We found that, between 2009/10 and 2016, DWV-A prevalence decreased, whilst DWV-B prevalence increased. The switch from DWV-A to DWV-B may be explained by the ability of DWV-B to replicate to higher loads than DWV-A [25, 26, 28, 40], which accounts for why DWV-B was detected at higher loads than DWV-A for both sample years. When coinfection with both variants occurs, the DWV-A viral load is initially higher than that of DWV-B, but at 72 hours post-inoculation, DWV-B replicates to higher loads [25]. Superinfection exclusion (SIE) occurs when a pre-existing viral infection prevents a secondary infection with a closely related virus [41]. SIE has been demonstrated for DWV-B, but only at the colony level, as it is yet to be proven if DWV-B can exclude DWV-A from cells or at the individual bee level [25, 28]. The detection of DWV-A/DWV-B recombinants [34] provides evidence that DWV-B cannot exclude DWV-A from entering the cell. However, at the colony level, DWV-B reaches saturation in populations. This may be because it is less lethal to pupae than DWV-A [25] and replicates to a higher load. However, it should be noted that the presence of other viruses may have confounded this result, as black queen cell virus (BQCV) was detected in the DWV-A inoculum in the cited study [25]. In another study in which the inocula did not contain any viruses other than DWV-A or DWV-B, pupal mortality was equal regardless of DWV variant or DWV coinfection. However, those injected with DWV-B had a higher viral load as adults than those injected with DWV-A [28]. Rather than excluding multiple infections within the host, it seems to be more likely that DWV-B competes with and gradually replaces DWV-A at the colony level.

The ability of DWV-B to replicate to higher loads than DWV-A provides a possible evolutionary advantage over DWV-A and may be an example of viral attenuation, since longer-term trends indicate Varroa-virus-associated overwintering losses may be declining [21, 42, 43]. Furthermore, evidence suggests that DWV-B is able to replicate in Varroa mites, while DWV-A cannot [44], and this may play a role in the increased prevalence of DWV-B in colonies. In the currently DWV-A-dominated USA [21, 31], the rate of decline is periodically higher than in other temperate regions [45]. Therefore, it is expected that, over time, DWV-A would lose dominance in honey bee populations, as evidenced here within. It is expected that colonies in the USA [21, 31] will eventually also switch to DWV-B dominance. Since DWV-A was not completely eradicated from the English honey bee colonies sampled, a re-emergence of DWV-A may occur, highlighting the need for long-term landscape level monitoring over time.

Mutation rates in RNA viruses are high, and a few single amino acid changes can alter the pathogenicity of a virus [46]. Nucleotide differences in the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) structures of DWV-A and DWV-B may provide DWV-B an evolutionary advantage over DWV-A [25]. The IRES secondary structure is an important feature for many RNA viruses, as IRES elements are used to initiate translation and the replication processes [47, 48]. The IRES elements of DWV-A and DWV-B are located at the 5’ end of the genome, and the secondary structures are predicted to be the same for both variants [49]. DWV-A and DWV-B have 84% nucleotide and 95% amino acid sequence identity [19] across the whole genome; however, comparison of the first 818 nucleotides shows a 65% sequence identity between DWV-A and DWV-B in the region where the IRES is located [49]. Mutations in the IRES have been shown to alter the virulence and replication efficiency of RNA viruses [50,51,52]. It is possible that evolution has favourably altered the success of DWV-B, allowing for this genotype to persist and outcompete or suppress other DWV variants in populations of honey bees. We propose that recombination is an important mechanism for viral variant switching, and there is some evidence in the literature to support this idea [11], since the earliest recorded recombinants were those between the structural genes of DWV-B and the non-structural genes of DWV-A. This study reports on a small region (RdRp) of the DWV genome and therefore does not include the detection of A/B recombinants; however, a subset of samples from 2016 for which recombination data exist has been provided in the supplementary data (Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Fig. S1).

In order for a Varroa mite to complete its life cycle, it must enter an occupied brood cell, where it will reproduce and feed on the honey bee haemolymph [53] and fat body tissue [54]. If Varroa vectors a pathogen that is deadly to the host, the mite and its progeny die too. By comparing feral Varroa-untreated and managed Varroa-treated colonies, we were able to investigate whether the mite influenced which DWV variants were detected. Although we cannot confirm the complete absence of Varroa in the treated managed colonies, feral colonies are expected to have higher Varroa levels. It was speculated that a virulence trade-off must occur between Varroa, DWV, and the host for DWV populations to be maintained in the environment; however, vector-borne virulence trade-offs are hard to prove [55]. We found a similar level of prevalence of DWV-A and DWV-B in feral and managed colonies in both sample years, although feral colonies had a higher prevalence of DWV-B. No significant differences were recorded when comparing the DWV-B load in feral and managed colonies for both years. The DWV-A level was significantly higher in the 2009/10 feral colonies than in the 2009/10 managed colonies. It was found that management did not influence which DWV variant was present; the only difference observed was an increase in the proportion of DWV-B positives between feral and managed colonies. In addition, previous work conducted on these samples showed that the season (spring/late autumn) had no bearing upon DWV load or DWV prevalence [21], although increasing Varroa numbers have been shown to increase the DWV load. It has been demonstrated recently that the DWV-A load increases along with Varroa population growth, whilst Varroa numbers do not influence DWV-B load [56]. Therefore, it is entirely possible that the bees themselves are maintaining DWV-B infections within the colony. More colony-level studies are required to understand virulence trade-offs and the factors that influence them, as this type of study is lacking in the available scientific literature.

So far, DWV-B dominance in honey bee colonies may be beneficial, as DWV-B-infected colonies appear to be healthier than those infected with DWV-A [23], indicating that the disease induced by DWV-B may be lessening in severity naturally. The exact mechanism underlying the advantageous nature of DWV-B over DWV-A has yet to be identified; however, we demonstrate that DWV-A prevalence was dramatically reduced from 2009/10 to 2016, which coincided with an increase in DWV-B. This may be explained by genetic variations between the DWV master variants that favor host cell invasion and replication, as well as a potential tradeoff in DWV virulence initiated by the Varroa vectoring cycle.

References

Higes M, Martin-Hernandez R, Botias C, Bailon EG, Gonzalez-Porto AV, Barrios L, Del Nozal MJ, Bernal JL, Jimenez JJ, Palencia PG, Meana A (2008) How natural infection by Nosema ceranae causes honeybee colony collapse. Environ Microbiol 10(10):2659–2669. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01687.x

Higes M, Martin-Hernandez R, Garrido-Bailon E, Gonzalez-Porto AV, Garcia-Palencia P, Meana A, Del Nozal MJ, Mayo R, Bernal JL (2009) Honeybee colony collapse due to Nosema ceranae in professional apiaries. Environ Microbiol Rep 1(2):110–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00014.x

Le Conte Y, Ellis M, Ritter W (2010) Varroa mites and honey bee health: can Varroa explain part of the colony losses? Apidologie 41(3):353–363. https://doi.org/10.1051/apido/2010017

McMenamin AJ, Genersch E (2015) Honey bee colony losses and associated viruses. Curr Opin Insect Sci 8:121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2015.01.015

Simon-Delso N, San Martin G, Bruneau E, Minsart LA, Mouret C, Hautier L (2014) Honeybee colony disorder in crop areas: the role of pesticides and viruses. PLoS ONE 9(7):e103073. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103073

Williams GR, Troxler A, Retschnig G, Roth K, Yanez O, Shutler D, Neumann P, Gauthier L (2015) Neonicotinoid pesticides severely affect honey bee queens. Sci Rep 5:14621. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14621

Naug D (2009) Nutritional stress due to habitat loss may explain recent honeybee colony collapses. Biol Conserv 142(10):2369–2372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2009.04.007

Clermont A, Eickermann M, Kraus F, Hoffmann L, Beyer M (2015) Correlations between land covers and honey bee colony losses in a country with industrialized and rural regions. Sci Total Environ 532:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.05.128

Goulson D, Nicholls E, Botias C, Rotheray EL (2015) Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science 347(6229):1255957. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255957

Martin SJ, Highfield AC, Brettell L, Villalobos EM, Budge GE, Powell M, Nikaido S, Schroeder DC (2012) Global honey bee viral landscape altered by a parasitic mite. Science 336(6086):1304–1306. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1220941

Wilfert L, Long G, Leggett HC, Schmid-Hempel P, Butlin R, Martin SJM, Boots M (2016) Deformed wing virus is a recent global epidemic in honeybees driven by Varroa mites. Science 351(6273):594–597. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac9976

Ryabov EV, Wood GR, Fannon JM, Moore JD, Bull JC, Chandler D, Mead A, Burroughs N, Evans DJ (2014) A virulent strain of deformed wing virus (DWV) of Honeybees (Apis mellifera) prevails after Varroa destructor-mediated, or in vitro, transmission. Plos Pathog. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004230

Martin SJ, Brettell LE (2019) Deformed wing virus in honeybees and other insects. Annu Rev Virol 6:49–69. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-virology-092818-015700

Benaets K, Van Geystelen A, Cardoen D, De Smet L, de Graaf DC, Schoofs L, Larmuseau MHD, Brettell LE, Martin SJ, Wenseleers T (2017) Covert deformed wing virus infections have long-term deleterious effects on honeybee foraging and survival. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.2149

Schroeder DC, Martin SJ (2012) Deformed wing virus: the main suspect in unexplained honeybee deaths worldwide. Virulence 3(7):589–591. https://doi.org/10.4161/viru.22219

Iqbal J, Mueller U (2007) Virus infection causes specific learning deficits in honeybee foragers. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 274(1617):1517–1521. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2007.0022

Traniello IM, Bukhari SA, Kevill J, Ahmed AC, Hamilton AR, Naeger NL, Schroeder DC, Robinson GE (2020) Meta-analysis of honey bee neurogenomic response links Deformed wing virus type A to precocious behavioral maturation. Sci Rep-Uk. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59808-4

Lanzi G, De Miranda JR, Boniotti MB, Cameron CE, Lavazza A, Capucci L, Camazine SM, Rossi C (2006) Molecular and biological characterization of deformed wing virus of honeybees (Apis mellifera L.). J Virol 80(10):4998–5009. https://doi.org/10.1128/Jvi.80.10.4998-5009.2006

Ongus JR, Peters D, Bonmatin JM, Bengsch E, Vlak JM, van Oers MM (2004) Complete sequence of a picorna-like virus of the genus Iflavirus replicating in the mite Varroa destructor. J Gen Virol 85:3747–3755. https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.80470-0

Mordecai GJ, Wilfert L, Martin SJ, Jones IM, Schroeder DC (2016) Diversity in a honey bee pathogen: first report of a third master variant of the Deformed Wing Virus quasispecies. Isme J 10(5):1264–1273. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2015.178

Kevill JL, de Souza FS, Sharples C, Oliver R, Schroeder DC, Martin SJ (2019) DWV-A Lethal to Honey Bees (Apis mellifera): a Colony Level Survey of DWV Variants (A, B, and C) in England, Wales, and 32 States across the US. Viruses-Basel. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11050426

Mordecai GJ, Brettell LE, Martin SJ, Dixon D, Jones IM, Schroeder DC (2016) Superinfection exclusion and the long-term survival of honey bees in Varroa-infested colonies. Isme J 10(5):1182–1191. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2015.186

Barroso-Arevalo S, Vicente-Rubiano M, Molero F, Puerta F, Sanchez-Vizcaino JM (2019) Nucleotide sequence variations may be associated with virulence of deformed wing virus. Apidologie 50(4):482–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-019-00660-5

Kevill JL, Highfield A, Mordecai GJ, Martin SJ, Schroeder DC (2017) ABC assay: method development and application to quantify the role of three DWV master variants in overwinter colony losses of European honey bees. Viruses-Basel. https://doi.org/10.3390/v9110314

Norton AM, Remnant EJ, Buchmann G, Beekman M (2020) Accumulation and competition amongst deformed wing virus genotypes in naive Australian honeybees provides insight into the increasing global prevalence of genotype B. Front Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00620

McMahon DP, Natsopoulou ME, Doublet V, Furst M, Weging S, Brown MJF, Gogol-Doring A, Paxton RJ (2016) Elevated virulence of an emerging viral genotype as a driver of honeybee loss. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.0811

Natsopoulou ME, McMahon DP, Doublet V, Frey E, Rosenkranz P, Paxton RJ (2017) The virulent, emerging genotype B of Deformed wing virus is closely linked to overwinter honeybee worker loss. Sci Rep-Uk. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05596-3

Tehel A, Vu Q, Bigot D, Gogol-Doring A, Koch P, Jenkins C, Doublet V, Theodorou P, Paxton R (2019) The two prevalent genotypes of an emerging infectious disease, deformed wing virus, cause equally low pupal mortality and equally high wing deformities in host honey bees. Viruses-Basel. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11020114

de Souza RS, Kevill JL, Correia-Aveira ME, de Carvalho CAL, Martin SJ (2019) Occurrence of deformed wing virus variants in the stingless bee Melipona subnitida and honey bee Apis mellifera populations in Brazil. J Gen Virol 100(2):289–294. https://doi.org/10.1099/jgv.0.001206

Brettell LE, Schroeder DC, Martin SJ (2019) RNAseq Analysis Reveals Virus Diversity within Hawaiian Apiary Insect Communities. Viruses-Basel. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11050397

Ryabov EV, Childers AK, Chen YP, Madella S, Nessa A, vanEngelsdorp D, Evans JD (2017) Recent spread of Varroa destructor virus-1, a honey bee pathogen, in the United States. Sci Rep-Uk. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17802-3

Baker A, Schroeder D (2008) Occurrence and genetic analysis of picorna-like viruses infecting worker bees of Apis mellifera L. populations in Devon, South West England. J Invertebr Pathol 98(2):239–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2008.02.010

Highfield AC, El Nagar A, Mackinder LCM, Noel LMLJ, Hall MJ, Martin SJ, Schroeder DC (2009) Deformed wing virus implicated in overwintering honeybee colony losses. Appl Environ Microb 75(22):7212–7220. https://doi.org/10.1128/Aem.02227-09

Moore J, Jironkin A, Chandler D, Burroughs N, Evans DJ, Ryabov EV (2011) Recombinants between Deformed wing virus and Varroa destructor virus-1 may prevail in Varroa destructor-infested honeybee colonies. J Gen Virol 92:156–161. https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.025965-0

Dalmon A, Desbiez C, Coulon M, Thomasson M, Le Conte Y, Alaux C, Vallon J, Moury B (2017) Evidence for positive selection and recombination hotspots in Deformed wing virus (DWV). Sci Rep-Uk. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41045

Fei DL, Guo YX, Fan Q, Wang HQ, Wu JD, Li M, Ma MX (2019) Phylogenetic and recombination analyses of two deformed wing virus strains from different honeybee species in China. PeerJ. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.7214

Thompson CE, Biesmeijer JC, Allnutt TR, Pietravalle S, Budge GE (2014) Parasite Pressures on Feral Honey Bees (Apis mellifera sp.). Plos One 9 (8). doi:ARTN e10516410.1371/journal.pone.0105164

Evans JD, Schwarz RS, Chen YP, Budge G, Cornman RS, De la Rua P, de Miranda JR, Foret S, Foster L, Gauthier L, Genersch E, Gisder S, Jarosch A, Kucharski R, Lopez D, Lun CM, Moritz RFA, Maleszka R, Munoz I, Pinto MA (2013) Standard methods for molecular research in Apis mellifera. J Apicult Res. https://doi.org/10.3896/Ibra.1.52.4.11

Kevill J (2019) The role of resistance to Varroa destructor and Deformed wing virus in the European honey bee (Apis mellifera). University of Salford

Dunn OJ (1961) Multiple comparisons among means. J Am Stat Assoc 56(293):52–000. https://doi.org/10.2307/2282330

Dubois E, Dardouri M, Schurr F, Cougoule N, Sircoulomb F, Thiery R (2020) Outcomes of honeybee pupae inoculated with deformed wing virus genotypes A and B. Apidologie 51(1):18–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-019-00701-z

Folimonova SY (2012) Superinfection exclusion is an active virus-controlled function that requires a specific viral protein. J Virol 86(10):5554–5561. https://doi.org/10.1128/Jvi.00310-12

BBKA (2019) Record low level of winter losses of honeybees. British Beekeepers Association. Accessed 06 May 2020

Brodschneider R, Gray A, Adjlane N, Ballis A, Brusbardis V, Charriere JD, Chlebo R, Coffey MF, Dahle B, de Graaf DC, Drazic MM, Evans G, Fedoriak M, Forsythe I, Gregorc A, Grzeda U, Hetzroni A, Kauko L, Kristiansen P, Martikkala M, Martin-Hernandez R, Medina-Flores CA, Mutinelli F, Raudmets A, Ryzhikov VA, Simon-Delso N, Stevanovic J, Uzunov A, Vejsnaes F, Wohl S, Zammit-Mangion M, Danihlik J (2018) Multi-country loss rates of honey bee colonies during winter 2016/2017 from the COLOSS survey. J Apicult Res 57(3):452–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2018.1460911

Gisder S, Genersch E (2021) Direct evidence for infection of Varroa destructor Mites with the bee-pathogenic deformed wing virus variant B, but not variant A, via fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis. J Virol. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01786-20

Gray A, Brodschneider R, Adjlane N, Ballis A, Brusbardis V, Charrire JD, Chlebo R, Coffey MF, Cornelissen B, da Costa CA, Cski T, Dahle B, Danihlk J, Drazic MM, Evans G, Fedoriak M, Forsythe I, de Graaf D, Gregorc A, Johannesen J, Kauko L, Kristiansen P, Martikkala M, Martn-Hernndez R, Medina-Flores CA, Mutinelli F, Patalano S, Petrov P, Raudmets A, Ryzhikov VA, Simon-Delso N, Stevanovic J, Topolska G, Uzunov A, Vejsnaes F, Williams A, Zammit-Mangion M, Soroker V (2019) Loss rates of honey bee colonies during winter 2017/18 in 36 countries participating in the COLOSS survey, including effects of forage sources. J Apicult Res 58(4):479–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2019.1615661

Domingo E, Sheldon J, Perales C (2012) Viral Quasispecies evolution. Microbiol Mol Biol R 76(2):159–216. https://doi.org/10.1128/Mmbr.05023-11

Martinez-Salas E (2008) The impact of RNA structure on picornavirus IRES activity. Trends Microbiol 16(5):230–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2008.01.013

Pfingsten JS, Costantino DA, Kieft JS (2006) Structural basis for ribosome recruitment and manipulation by a viral IRES RNA. Science 314(5804):1450–1454. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1133281

Ongus JR, Roode EC, Pleij CWA, Vlak JM, van Oers MM (2006) The 5 ’ non-translated region of Varroa destructor virus 1 (genus lflavirus): structure prediction and RES activity in Lymantria dispar cells. J Gen Virol 87:3397–3407. https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.82122-0

Gromeier M, Alexander L, Wimmer E (1996) Internal ribosomal entry site substitution eliminates neurovirulence in intergeneric poliovirus recombinants. P Natl Acad Sci USA 93(6):2370–2375. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.93.6.2370

Kauder SE, Racaniello VR (2004) Poliovirus tropism and attenuation are determined after internal ribosome entry. J Clin Invest 113(12):1743–1753. https://doi.org/10.1172/Jci200421323

Orlinger KK, Kofier RM, Heinz FX, Hoenninger VM, Mandl CW (2007) Selection and analysis of mutations in an encephalomyocarditis virus internal ribosome entry site that improve the efficiency of a bicistronic flavivirus construct. J Virol 81(22):12619–12629. https://doi.org/10.1128/Jvi.01017-07

Rosenkranz P, Aumeier P, Ziegelmann B (2010) Biology and control of Varroa destructor. J Invertebr Pathol 103:S96–S119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2009.07.016

Ramsey SD, Ochoa R, Bauchan G, Gulbronson C, Mowery JD, Cohen A, Lim D, Joklik J, Cicero JM, Ellis JD, Hawthorne D, vanEngelsdorp D (2019) Varroa destructor feeds primarily on honey bee fat body tissue and not hemolymph. P Natl Acad Sci USA 116(5):1792–1801. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1818371116

Froissart R, Doumayrou J, Vuillaume F, Alizon S, Michalakis Y (2010) The virulence-transmission trade-off in vector-borne plant viruses: a review of (non-)existing studies. Philos T R Soc B 365(1548):1907–1918. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0068

Norton AM, Remnant EJ, Tom J, Buchmann G, Blacquiere T, Beekman M (2021) Adaptation to vector-based transmission in a honey bee virus. J Anim Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13493

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Martin Smith of Bee Disease Insurance (BDI) Ltd, the British and Welsh beekeepers, the National Bee Unit, and Dr. Catherine Thompson. Funding to the Schroeder Lab was through a joint award by the BDI, CB Dennis Trust, and BBKA.

Funding

This project was funded by the British Beekeepers Association (BBKA), Bee Disease Insurance (BDI) Ltd, CB Dennis Trust, Defra and Welsh government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, JLK, SJM, and KCS; methodology, JLK and KCS; validation, JLK and KCS; formal analysis JLK; investigation, JLK and KCS; resources, SJM, DCS and KCS; data curation, JLK and KCS; writing original draft JLK; review and editing, JLK, SJM, KCS, and DCS All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Simona Abba'.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kevill, J.L., Stainton, K.C., Schroeder, D.C. et al. Deformed wing virus variant shift from 2010 to 2016 in managed and feral UK honey bee colonies. Arch Virol 166, 2693–2702 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-021-05162-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-021-05162-3