Abstract

Using a panel of establishments from the annual survey of industries, I study the impact of the 1991 trade liberalization episode in India on the employment share of women. Contrary to the predictions of a taste-based discrimination model, I find that establishments exposed to larger output tariff reductions and import competition reduced the share of female workers. I also find that input tariff reductions neither raised nor reduced female employment share. The negative association between output tariff reductions and female employment appears to be driven by establishments which increased the number of shifts per worker. Since women in India are prohibited by law from working long hours and night shifts, this hours-constraint appears to have reduced relative employment of women. This paper is the first to provide empirical evidence of how an ostensibly pro-women policy of limiting female work hours might have unintended side effects. In order to look at the overall effects of liberalization on the gender employment share, I use Census of India data to create a district level panel. I find that districts which were more exposed to the reforms experienced a reduction in the share of female workers. This was observed for both urban and rural areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I include only large establishments in the establishment-level panel as these are the census of all establishments in that category. I aggregate both the large and small establishments at the industry level and construct an industry level panel for the formal sector manufacturing establishments. See section Data for more details.

In the context of this study, I find that the output tariff change is also uncorrelated with the log female to male share in man-days in 1989, the log skill ratio in 1989 and log male intensity in 1989 at the industry level (the results are presented in Table 12).

See Data Section below for more details.

All establishments with 100 workers or above were surveyed in 1989, and all establishments with 200 workers or above were surveyed in 1998.

I aggregate up to 3-digit industry level. There are 90 industries.

I also look at the panel of smaller establishments. I do not include the results for smaller establishments in the paper since, in the ASI data, only a sample of the small establishments were reported in both years. Also, the sampling technique changed between 1989 and 1998. Earlier, 1/3rd of the firms were sampled, which changed to 1/7th. So if a small establishment was not part of the panel, one is not sure if it did not exist that year or was left out sampled because of the sampling scheme. The ASI provides multipliers for sampled establishments, which is a measure of the probability of being sampled. These were used to calculate the aggregates for the industry level.

see Appendix Table 13.

In my analysis, I do not look at the change in relative wages, as I do not have information for wages for the “pre” period in the ASI. Figure 3 shows that the correlation between log ratio of female to total share in man-days and log ratio of female to total share in the wage bill for 1998 is 0.95.

The change in tariffs is in percentage points.

I am grateful to Reshad Ahsan and Debashish Mitra for sharing their tariff data.

These classifications were revised between 1989 and 1998. I converted all industry classifications to the 1998 NIC codes using concordance tables provided by Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation (MOSPI).

Input tariffs were constructed by Ahsan and Mitra (2014) using the formula used by Amiti et al. (2012). Consider industry j that uses inputs from industry k. In this case \(\text{ Input } \text{ Tariff}_{jt}=\sum _{k}s_{jk}*\text{ Output } \text{ Tariff}_{kt}\), where \( s_{jk}\) is the share of input k used in producing output j. The share of inputs are obtained from the relevant input–output tables.

For convenience, however, I will use the terms “firm” and “establishment” interchangeably in the paper.

These are registered under the Factories Act of 1948. This includes all establishments using 10 or more workers if using power and 20 or more workers if not using power.

I use the detailed unit level data from the annual survey of industries. This is the most detailed version of the ASI data which gives the breakup of hours and employment by establishments for production workers. The ASI provides data at a greater level of aggregation such as summary data and industry level , all of which are used by some recent papers such as Banerjee and Veeramani (2017), Adhvaryu et al. (2013) and Nataraj (2011).

All establishments with 100 workers or above were surveyed in 1989 and all establishments with 200 workers or above were surveyed in 1998.

The sample scheme surveyed approximately one third of the establishments below the size cut-off every year, subject to the constraint that a sufficient number of establishments were sampled to assure representativeness at the state and industry level.

Around 43.40% of the big establishments in 1989 are matched and included in the panel data set. This is expected, given that Hsieh and Klenow (2014) find that the exit rate of large establishments is around 4% every year. The match rate among smaller establishments is even lower. Around 7% of the smaller establishments in the 1989 sample are matched and included in the panel data set.

Following the size cut-offs for being in the census of establishments, I classify establishments with > 60,000 man-days as “big” establishments. This definition of the census sector is taken according to 1998. However, only 5% of these establishments were not part of the census sector in 1989. Even if I drop these 5% establishments, the results remain similar. Also, I do not find any correlation between change in tariff and the total size of establishments.

The summary tables for the cross section are given in Table 15. The share of female to total man-days and numbers are slightly lesser in the panel establishments than in the cross section. In my analysis, I look at the percentage change in female shares in response to change in tariffs. When I include all the establishments and aggregate up to the industry, the direction of change is similar and statistically significant.

The 1991 census data was used by Topalova (2010) to construct the district level tariff intensity measures.

This is similar to usual activity status in the NSS data.

NIC 1987 codes 200 to 400.

I also look at the change in ratio of female to total man-days (in levels) and find no difference in results.

Years for outcome variables are 1991 and 2001. Using lagged tariffs should not make a lot of difference to the analysis as most of the tariff changes occurred between 1989 and 1997 (Fig. 5).

I also use the same specification as Topalova (2010) and the results remain similar.

I cluster standard errors at the 3-digit industry level.

I have also interacted the importer dummy with input tariff changes to check for differential effects and found none of the interactions to be statistically significant.

Figure 4 shows that the correlation between output and input tariff is 0.61.

The IT sector is not subject to these restrictions. Begum (2013) studies the effect of night shifts on the health of women in the IT sector. Recent newspaper articles reported that states are actively considering repealing this section of the Act. The state governments have been given authority to make amendments to the law.

The years are 2000 to 2007 which is much after our reference period. I assume here that the enforcement intensity in states have not undergone major changes.

In Table 17 columns (4) and (5), I look at the change in log ratio of plant and machinery to man-days and the change in log ratio of fixed capital to sales as alternative measures of skill upgrading. However, I do not observe evidence of skill upgrading with respect to output tariff changes.

I take controls for import status of the establishment in the initial year. As mentioned earlier, I do not have information on the export status of establishments. In order to take care of this issue, I take the share of fixed capital to sales and working capital to sales and use them as a proxy for exports.

In column (3), I look at the change in log ratio of total sales to man-days and find that there is a decline overall with respect to a decline in output as well as input tariffs.

References

Adhvaryu, A., A. Chari, and S. Sharma. 2013. Firing Costs and Flexibility: Evidence From Firms’ Employment Responses to Shocks in India. Review of Economics and Statistics 95(3): 725–740.

Afridi, F., T. Dinkelman, and K. Mahajan. 2017. Why are Fewer Married Women Joining the Workforce in India? A Decomposition Analysis Over Two Decades. Journal of Population Economics 31(3): 783–818.

Aguayo-Tellez, E., J. Airola, C. Juhn and C. Villegas-Sanchez. 2013. Did Trade Liberalization Help Women? the case of Mexico in the 1990s. Research in Labor Economics, in: Solomon W. Polachek & Konstantinos Tatsiramos (ed.), New Analyses of Worker Well-Being, volume 38, pages 1-35, Emerald Publishing Ltd.

Ahsan, R. 2013. Input Tariffs, Speed of Contract Enforcement, and the Productivity of Firms in India. Journal of International Economics 90(1): 181–192.

Ahsan, R. N. and D. Mitra. 2014. Trade Liberalization and Labor’s Slice of the Pie: Evidence from Indian Firms. Journal of Development Economics 108(C): 1–16.

Ahsan, R., R. Hasan, D. Mitra, and P. Ranjan. 2012. Trade Liberalization and Unemployment: Theory and Evidence from India. Journal of Development Economics 97(2): 269–280.

Amiti, M., L. Cameron, and D.R. Davis. 2012. Trade Liberalization and the Wage Skill Premium: Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of International Economics 87(2): 277–287.

Autor, D.H., D. Dorn, and G.H. Hanson. 2013. The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States. American Economic Review 103(6): 2121–2168.

Banerjee, P., and C. Veeramani. 2017. Analysis of India’s Manufacturing Industries: Trade Liberalisation and Women’s Employment Intensity. Economic and Political Weekly 52(35): 37.

Becker, G. 1957. The Economics of Discrimination. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Begum, Kousar, and Jahan Ara. 2013. WOMEN and BPOs in INDIA. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention 2: 2319–7722.

Berman, E., R. Somanathan, and H. Tan. 2005. Is Skill-Biased Technological Change Here Yet: Evidence from Indian Manufacturing in the 1990s. Annals of Economics and Statistics, GENES, (79-80): 299–321.

Bertrand, M., K. Goldin, and L.F. Katz. 2010. Dynamics of the Gender Gap for Young Professionals in the Finance and Corporate Sectors. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2: 228–255.

Besley, T., and R. Burgess. 2004. Can Labor Regulation Hinder Economic Performance? Evidence from India. Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(1): 91–134.

Bhalotra, S. 1998. The Puzzle of Jobless Growth in Indian Manufacturing. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 60(1): 0305–9048.

Black, S., and E. Brainerd. 2004. Importing Inequality? The Impact of Globalization on Gender Discrimination. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 57(4): 540–559.

Bollard, A., P.J. Klenow, and G. Sharma. 2013. India’s Mysterious Manufacturing Miracle. Review of Economic Dynamics 16: 59–85.

Currie, J., and A. Harrison. 1997. Trade Reform and Labor Market Adjustment in Morocco. Journal of Labor Economics 15: S44-71.

Desai, S., R. Vanneman, and NCAER. 2005. India Human Development Survey (IHDS), 2018-08-08. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR22626.v12, Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research [Distributor].

Deshpande, A. and N. Kabeer. 2019. (In)Visibility, Care and Cultural Barriers: The Size and Shape of Women’s Work in India. Discussion Paper Series in Economics, No 10, Department of Economics, Ashoka University.

Dix-Carnerio, R., and B. Kovak. 2015. Trade Liberalization and the Skill Premium: A Local Labor Markets Approach. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 105: 551–557.

Duflo, E. 2003. Grandmothers and Granddaughters: Old Age Pension and Intra-household Allocation in South Africa. World Bank Economic Review 17(1): 1–25.

Duflo, E. 2012. Women Empowerment and Economic Development. Journal of Economic Literature 50(4): 1051–1079.

Ederington, J., J. Minier, and K. Troske. 2010. Where the Girls Are: Trade and Labor Market Segregation in Colombia, Lexington, KY. New York: University of Kentucky.

Edmonds, E., N. Pavcnik, and P. Topalova. 2010. Trade Adjustment and Human Capital Investments: Evidence from Indian Tariff Reform. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2(4): 42–75.

Feliciano, Z. 2001. Workers and Trade Liberalization: The Impact of Trade Reforms in Mexico on Wages and Employment. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 55(1): 95–115.

Fletcher, K., R. Pande, and C. T. Moore. 2017. Women and Work in India: Descriptive Evidence and a Review of Potential Policies. CID Faculty Working Paper No. 339. Center for International Development at Harvard University.

Gaddis, I., and J. Pieters. 2017. The Gendered Labor Market Impacts of Trade Liberalization: Evidence from Brazil. Journal of Human Resources 52: 457–490.

Goldberg, P., A. Khandelwal, N. Pavcnik, and P. Topalova. 2009. Trade Liberalization and New Imported Inputs. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 99(2): 494–500.

Goldberg, P., A. Khandelwal, N. Pavcnik, and P. Topalova. 2010. Imported Intermediate Inputs and Domestic Product Growth: Evidence from India. Quarterly Journal of Economics 125(4): 1727–1767.

Goldberg, P.K., A. Khandelwal, N. Pavcnik, and P. Topalova. 2010. Multi-product Firms and Product Turnover in the Developing World: Evidence from India. Review of Economics and Statistics 92(4): 1042–1049.

Goldberg, P. K., and N. Pavcnik. 2007. Distributional Effects of Globalisation in Developing Countries. NBER Working Papers 12885, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Goldin, K., and L.F. Katz. 2011. The Cost of Workplace Flexibility for High-Powered Professionals. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 638: 45–67.

Gupta, A. and J. Pieters. 2018. Poverty and Gender Inequality: Household Responses to India’s Trade Reforms. Unpublished Manuscript.

Hanson, G., and A. Harrison. 1999. Who Gains from Trade Reform? Some Remaining Puzzles. Journal of Development Economics 59: 125–154.

Hasan, R., D. Mitra, and K.V. Ramaswamy. 2007. Trade Reforms, Labor Regulations and Labor Demand Elasticities: Empirical Evidence from India. Review of Economics and Statistics 89(3): 466–481.

Hsieh, C.-T. and P. J. Klenow. 2014. The Life Cycle Of Plants In India And Mexico. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(3): 1035–1084.

Jayachandran, Seema. 2015. The Roots of Gender Inequality in Developing Countries. Annual Review of Economics 7(1): 63–88.

Juhn, C., G. Ujhelyi, and C. Villegas-Sanchez. 2014. Men, Women, and Machines: How Trade Impacts Gender Inequality. Journal of Development Economics 106: 179–193.

Khandelwal, A., and P. Topalova. 2011. Trade Liberalization and Firm Productivity: The Case of India. The Review of Economics and Statistics 93(3): 995–1009.

Kijama, Y. 2006. Why did Wage Inequality Increase? Evidence from Urban India 1983–99. Journal of Development Economics 81: 97–117.

Kis-Katos, K., J. Pieters, and R. Sparrow. 2018. Globalization and Social Change: Gender-Specific Effects of Trade Liberalization in Indonesia. IMF Economic Review 66: 763–793.

Klasen, S., and J. Pieters. 2015. What Explains Stagnation of Female Labor Force Participation in Urban India? World Bank Economic Review 29: 448–478.

Klasen, S. S. Sahoo and S. Sarkar. 2017. Employment Transitions of Women in India: A Panel Analysis. World Development 115: 291–309.

Kovak, B.K. 2013. Regional Effects of Trade Reform: What Is the Correct Measure of Liberalization? American Economic Review 103(5): 1960–76.

Krishna, P., and D. Mitra. 1998. Trade Liberalization, Market Discipline and Productivity Growth: New Evidence From India. Journal of Development Economics 56(2): 447–462.

Kumar, U., and P. Mishra. 2008. Trade Liberalization and Wage Inequality: Evidence from India. Review of Development Economics 12(2): 291–311.

Menon, N., and Y. Rodgers. 2009. International Trade and Gender Wage Gap: New Evidence from India’s Manufacturing Sector. World Development 37(5): 965–981.

Nataraj, S. 2011. The Impact of Trade Liberalization on Productivity: Evidence from India’s Formal and Informal Manufacturing Sectors. Journal of International Economics 85(2): 292–301.

Oster E. and B. S. Millett. 2013. Do IT Service Centers Promote School Enrollment? Evidence from India. Journal of Development Economics 104(C): 123–135.

Qian, N. 2008. Missing Women and the Price of Tea in China: The Effect of Sex-Specific Earnings on Sex Imbalance. Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(3): 1251–1285.

Revenga, A. 1997. Employment and Wage Effects of Trade Liberalization: The Case of Mexican Manufacturing. Journal of Labor Economics 15: 20–43.

Sapkal, R.S. 2016. Labour Law, Enforcement and the Rise of Temporary Contract Workers: Empirical Evidence from India’s Organised Manufacturing Sector. European Journal of Law and Economics 42(1): 157–182.

Sen, A. 2001. Many Faces of Gender Inequality. New Republic: Harvard University Press.

Sharma, S. 2018. Heterogeneity of Imported Intermediate Inputs and Labour: Evidence from India’s Input Tariff Liberalization. Applied Economics 50(11): 635–664.

Sundaram, K. and S. Tendulkar. 1988. An Approximation to the Size Structure of Indian Manufacturing Industry. In ed. K. B. Suri, Ed., Small Scale Enterprises in Industrial Development, Sage Publication, New Delhi.

Tejani, S. 2016. Jobless Growth in India: An Investigation. Cambridge Journal of economics 40: 49–57.

Thomas, D. 1990. Intra-household Resource Allocation: An Inferential Approach. The Journal of Human Resources 25(4): 635–664.

Thorat, A. 2004. NSS Employment Surveys; Problems in Comparisons Over Time. http://www.networkideas.org/doc/sep2004/nss_data_critique.pdf.

Topalova, P. 2010. Factor Immobility and Regional Impacts of Trade Liberalization: Evidence on Poverty from India. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2(4): 1–41.

UNDP. 2016. Human Development Report. United Nations Development Program: Technical Report.

UNDP. 2018. Human Development Report 2016. Human Development for Everyone. New York. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-2016.

Acknowledgements

This work was done as part of my Ph.D. dissertation at the university of Houston. I am thankful to Chinhui Juhn, Aimee Chin and Elaine Liu for their useful comments and suggestions. I am also thankful to the faculty and my fellow graduate students at the university of Houston for useful discussions. I thank university of Houston for the research support. I also thank the faculty and students at Wageningen University for various useful comments. I thank Janneke Pieters, Reshad Ahsan, Sourav Chakraborty, Allan Collard-Wexler, Siddharth Kothari and Shaibal Gupta for providing very insightful suggestions and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

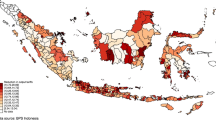

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

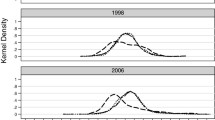

See Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and Tables 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21.