Abstract

HDL is a complex macromolecular cluster of various components, such as apolipoproteins, enzymes and lipids. Quality evidence from clinical and epidemiological studies led to the principle that HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) levels are inversely correlated with the risk of CHD. Nevertheless, the failure of many cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors to protect against CVD casts doubts on this principle and highlights the fact that HDL functionality, as dictated by its proteome and lipidome, also plays an important role in protecting against metabolic disorders. Recent data indicate that HDL-C levels and HDL particle functionality are correlated with the pathogenesis and prognosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus, a major risk factor for CVD. Hyperglycaemia leads to reduced HDL-C levels and deteriorated HDL functionality, via various alterations in HDL particles’ proteome and lipidome. In turn, reduced HDL-C levels and impaired HDL functionality impact the performance of key organs related to glucose homeostasis, such as pancreas and skeletal muscles. Interestingly, different structural alterations in HDL correlate with distinct metabolic abnormalities, as indicated by recent data evaluating the role of apolipoprotein A1 and lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase deficiency in glucose homeostasis. While it is becoming evident that not all HDL disturbances are causatively associated with the development and progression of type 2 diabetes, a bidirectional correlation between these two conditions exists, leading to a perpetual self-feeding cycle.

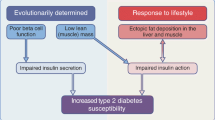

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

HDL consists of a variety of components, such as apolipoproteins, enzymes and lipids. HDL particles display large heterogeneity regarding their size, density, composition and hence functionality [1]. Proteomic analyses have revealed the presence of more than 85 different proteins in the HDL particle population [1, 2]. Apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA-1) is the main protein in this population but other apolipoproteins, such as apolipoprotein E (ApoE), apolipoprotein A2 (ApoA-2) and apolipoprotein C3 (ApoC-3), are also involved in HDL biogenesis [3].

The inverse correlation between HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) levels and the risk of CHD [4,5,6] highlights the role of HDL-C in health and disease. New evidence suggests that in addition to HDL-C levels, particle quality is very important [1]. Functional HDL has been reported to possess anti-atherosclerotic and antioxidant properties by which it prevents oxidised LDL (ox-LDL)-mediated endothelial dysfunction [3]. It also inhibits endothelial adhesion and leucocyte and platelet activation [7]. The anti-inflammatory effect of HDL is due to the alleviation of inflammation and immune activation at the site of atherosclerosis [1]. There is also evidence supporting the notion that these properties of HDL not only protect the coronary vessel wall against atherosclerosis but also directly benefit the myocardium [8]. Finally, HDL possibly acts as a coronary vasodilator via release of NO, leading to enhanced myocardial perfusion.

Recent studies have demonstrated that HDL proteome dictates both its lipidome and its functionality [3] and that different apolipoprotein-containing HDL particles have distinct functional properties. In one clinical paradigm, morbidly obese individuals had primarily ApoE-containing HDL (ApoE-HDL) and ApoC-3-containing HDL (ApoC-3-HDL), while after rapid weight loss following bariatric surgery they had primarily ApoA-1-containing HDL (ApoA-1-HDL) associated with significantly improved antioxidant properties [9]. In another clinical paradigm, young asymptomatic individuals who suffered an acute non-fatal myocardial infarction had elevated plasma ApoE-HDL and ApoC-3-HDL, correlated with reduced antioxidant activity [10]. Additional studies in mice support the notion that ApoA-1-HDL is functionally distinct from ApoE-HDL and ApoC-3-HDL. Specifically, only ApoA-1-HDL, ApoA-2-containing HDL (ApoA-2-HDL) and ApoC-3-HDL demonstrated significant antioxidant activity while ApoE-HDL had only a marginal capacity in inhibiting dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR123) oxidation [11,12,13]. When HDL particles were compared according to their ability to promote cholesterol efflux, ApoA-1-HDL turned out to be the most efficient, followed by ApoC-3-HDL, while ApoE-HDL and ApoA-2-HDL had the lowest ability [11,12,13]. Regarding anti-inflammatory activity, this has been demonstrated only for ApoE-HDL and ApoA-2-HDL, while ApoA-1-HDL and ApoC-3-HDL were found to have proinflammatory activity [11,12,13]. Therefore, not all HDL particles are equally active and the net impact of HDL is highly dependent on the relative amounts of HDL sub-particles present in circulation. However, it remains unclear which HDL functions are clinically relevant to human health and disease, and to what extent [2].

HDL pharmacology

Although high HDL-C levels in plasma were initially considered to be protective against the development of atherosclerosis, evidence from Mendelian randomisation analysis of several studies on SNPs of gene loci related to plasma HDL-C (LIPG, MLXIPL ABCA1, MMAB, MVK, TTC39B, LCAT, FADS1-FADS2-FADS3, LIPC, HNF4A) suggests that a causative relationship between HDL-C levels and CVD cannot be established [14, 15]. Recently, data from a meta-analysis of a genome-wide association study (GWAS) with 188,577 participants were analysed regarding 140 lipid-related SNPs and their relationship with type 2 diabetes [16]. Significant associations were found between gene variants determining higher LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) levels and lower type 2 diabetes risk, consistent with another study showing that lower plasma LDL-C due to specific polymorphism in HMGCR (the gene encoding the intended target of statins) appeared to associate with higher BMI and higher type 2 diabetes risk [17]. Nevertheless, no clear associations were found between genetically determined levels of plasma HDL-C, triacylglycerols (TAGs) and glucose levels, insulin secretion, or insulin sensitivity in diabetic or non-diabetic individuals. It should be noted, however, that Mendelian randomisation studies of this type suffer the major limitation that plasma lipoprotein concentrations are influenced by a wide variety of loci. Besides this, genetic variants that affect lipoprotein plasma levels have pleiotropic effects on other risk factors. In addition, plasma lipids are present in the circulation as structural components of lipoproteins and their levels are greatly affected by the biochemical mechanisms involved in lipoprotein metabolism. Efforts to overcome such limitations focus on incorporating the so-called allele scores, which appear to provide more powerful genetic instruments for complex traits [18]. Another way to overcome such challenges is to analyse data from large GWAS datasets using inverse variance-weighted and Mendelian randomisation Egger methods. Such methods provide the opportunity to re-address the effect of pleiotropy on the association between lipid levels and the metabolic syndrome [19].

Α recent epidemiological study fine-tuned the hypothesis that elevated HDL-C levels affect cardiovascular health and suggested that there is a U-shaped relationship between HDL-C levels and CVD and all-cause mortality [20]. Low HDL-C levels (<1.036 mmol/l [40 mg/dl]) are associated with increased risk for CVD and all-cause mortality [20,21,22], while increasing the HDL-C levels results in substantial reduction in CVD risk [23]. HDL-C levels of between 1.036 and 1.813 mmol/l (40–70 mg/dl) correspond to the lowest risk for CVD and all-cause mortality [20]. Though HDL-C levels over 1.813 mmol/l (70 mg/dl), present in a very small percentage of the general population, correlate to gradually increased risk for CVD and all-cause mortality [20], this does not necessarily preclude a substantial benefit when raising ones HDL-C from below 1.036 mmol/l (40 mg/dl) to levels between 1.036 and 1.813 mmol/l (40–70 mg/dl).

The failure of cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors torcetrapib, dalcetrapib and evacetrapib to prove effective against CVD [24] casted significant doubt on the clinical relevance of HDL-C-raising strategies. Nonetheless, it is still unclear whether the lack of pharmacological efficacy was specific to these agents and whether they were the most suitable drugs for testing the HDL-C-raising hypothesis. Evidence suggests that lack of efficacy of CETP inhibitors may not be a class effect since anacetrapib resulted in an 18% reduction in mortality rate vs placebo, when administered on top of a statin in the REVEAL clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov registration no. NCT01252953) [25]. Along the same lines, when nicotinic acid (niacin) was declared ineffective against CVD, the quality of clinical evidence from the AIM-HIGH (ClinicalTrials.gov registration no. NCT00120289) and the HPS2-THRIVE (ClinicalTrials.gov registration no. NCT00461630) clinical trials was very low and highly questionable due to design flaws [26]. Indeed, in the AIM-HIGH trial, Niaspan (extended-release nicotinic acid) was administered in patients receiving maximal intensive lipid-lowering therapy with statin and ezetimibe, who already had a median plasma LDL-C level of 1.86 mmol/l (72 mg/dl) and median plasma TAG level of 1.84 mmol/l (163 mg/dl) [27]. According to the most recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) guidelines, most individuals with such LDL-C and TAG levels are within goal. Similarly, when Tredaptive (laropiprant and nicotinic acid) was tested in HPS2-THRIVE, the presence of laropiprant, a prostaglandin D2 receptor antagonist, could have blunted the pharmacological efficacy of nicotinic acid against atherosclerosis [28]. Importantly, very recent evidence from the REDUCE IT trial (Clinicatrials.gov registration no. NCT01492361) suggests that lowering plasma TAG levels by 0.44 mmol/l (39 mg/dl) with icosapent ethyl is effective in reducing CVD death and myocardial infarctions in individuals with hypertriacylglycerolaemia. Similar data are also available for other TAG-lowering agents such as pemafibrate (PROMINENT clinical trial; ClinicalTrials.gov registration no. NCT03071692). Since plasma HDL-C levels show an inverse relationship to plasma TAG levels, it might be hypothesised that any HDL-C-raising strategy that markedly decreases TAG levels will benefit hypertriacylglycerolaemic individuals at risk for a heart attack. Considering this, HDL-C-raising drugs must be carefully re-examined in proper clinical trials and in suitable individuals, such as those who are hypertriacylglycerolaemic with increased CVD risk. For example, nicotinic acid, which can increase HDL-C by 30%, and lower TAG by 30%, LDL-C by 14% and lipoprotein (a) by 32%, is one such suitable candidate and its case should be re-opened. It should be noted, however, that despite the demonstrated beneficial effect on atherosclerosis of lowering TAG levels no direct benefit on dysglycaemia is expected.

Animal studies with recombinant human ApoA-1 and sphingomyelin (CER-001) revealed a regression of atherosclerotic lesions [29], an effect that was not observed in on-statin patients with acute coronary syndrome [30]. A single infusion of another recombinant HDL formulation (native ApoA-1 and phospholipids [CSL-111]) in individuals with documented coronary artery disease led to reduced lipid content in the plaque, increased HDL-C levels and cholesterol efflux capacity [31]. However, in another randomised controlled study, CSL-111 failed to reduce atherosclerotic plaque while an increase in liver enzymes levels led to suspension of its further development [32]. The newest formulation of human ApoA-1 (human plasma-derived ApoA-1 and phosphatidylcholine [CSL-112]) demonstrated great efficacy in enhancing cholesterol efflux as well as promoting beneficial modifications in plaque lipid composition [33, 34]. Currently, the phase III clinical trial Study to Investigate CSL-112 in Subjects With Acute Coronary Syndrome (AEGIS-II) is recruiting volunteers to evaluate the efficacy and safety of CSL-112 in reducing the risk of major cardiovascular events in individuals with acute coronary syndrome [35]. The clinical benefits of CSL-112 in diabetes have not been investigated thus far.

Another HDL-related pharmacological strategy that has been tested involves HDL-mimetic peptides. ApoA-1 mimetic peptides could be a promising therapeutic approach in the management of atherosclerosis, since they prevent lipoprotein oxidation and promote cholesterol efflux [36]. Specifically, D-4F peptides have been shown to bind more efficiently than endogenous ApoA-1 to oxidised lipids [37], while animal studies have revealed that they also increase cholesterol efflux, prevent LDL oxidation and reduce atherosclerotic lesions and the expression of endothelial cell vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) [38, 39]. Furthermore, the first-in-human multiple-dose, randomised controlled trial in high-risk individuals demonstrated that D-4F reduced HDL inflammatory index [40]. However, its effects on type 2 diabetes were not evaluated.

Type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes, a metabolic disorder characterised mainly by elevated blood glucose levels, constitutes a major global health burden, being among the top ten causes of death in adults. According to the WHO in 2014, 422 million people were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, increasing the global prevalence of the disease from 4.7% (in 1980) to 8.5%. Furthermore, it is estimated that the global prevalence will be 10.2% (578 million) by 2030 and 10.9% (700 million) by 2045 [41].

Fasting plasma glucose levels increase when beta cells become unable to produce or secrete sufficient amounts of insulin to meet metabolic demands, or when peripheral insulin-sensitive tissues lose their ability to respond to insulin stimulus, and hence develop insulin resistance [1]. Insulin resistance usually precedes the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and is accompanied by a characteristic dyslipidaemia, marked by elevated TAGs and NEFA, low levels of HDL-C and the predominance of the atherogenic small dense LDL particles [42]. Diabetic dyslipidaemia develops mainly due to impaired insulin sensitivity of adipose tissue and liver. In adipose tissue, insulin inhibits hormone-sensitive lipase leading to increased TAG storage while it influences TAG formation by promoting glucose absorption and its conversion to glycerol-3-phosphate and then to TAGs. When adipose tissue becomes insulin resistant, uncontrolled lipolysis is observed due to decreased hormone-sensitive lipase inhibition and glucose absorption, leading to increased circulating NEFA [42]. In the liver, insulin downregulates TAG-rich lipoprotein production, meaning that in insulin-resistant states, increased circulating VLDL is observed due to hepatic overproduction [42].

The existence of low HDL-C and increased TAG levels in diabetic dyslipidaemia suggest that a correlation between HDL-C and the development and progression of type 2 diabetes may exist.

Impact of type 2 diabetes on HDL

It is believed that the hyperglycaemia and hyperinsulinaemia that develop in type 2 diabetes may impact the structure as well as the functions of HDL [1] (Fig. 1). Indeed, insulin resistance and dyslipidaemia are inversely correlated with HDL-C levels, HDL particle size and diameter. As seen in NMR studies, the HDL population in type 2 diabetes consists mostly of small TAG-rich HDL particles accompanied by loss of large and very large particles [43]. The intensive formation of small HDL particles and the reduced overall HDL-C levels may be attributed to abnormal HDL metabolism, explained by either increased catabolic rate or impaired maturation and decreased biogenesis [44]. The precise mechanism for this phenomenon remains unknown and existing interpretations are based on HDL-C levels that, considering the importance of HDL functionality in type 2 diabetes, may be inadequate. It has been proposed that large amounts of VLDL are synthesised and secreted by the liver in response to increased levels of carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein (ChREBP) and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP1c) due to hyperinsulinaemia and hyperglycaemia [45], which in turn upregulates CETP expression, thereby facilitating HDL depletion from cholesteryl esters (CEs) and its enrichment with TAGs. Though not proven, it was suggested that such TAG enrichment could render HDL particles more susceptible to hydrolysis by hepatic and endothelial lipases, thereby reducing their size even further [46] and facilitating their interaction with scavenger receptor class B type 1 (SRB1) [47]. It is also proposed that due to lipid loss ApoA-1 could dissociate from HDL, leading to its subsequent catabolism [48].

Depiction of the functional crosstalk between HDL and type 2 diabetes. Type 2 diabetes impacts the quantity, composition and function of HDL, which in turn affects the secretory capacity of beta cells in pancreatic islets and skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity in a perpetual self-feeding cycle. FA, fatty acid. This figure is available as a downloadable slide

This hypothesis agrees with the altered proteomic composition of HDL particles that is commonly reported in the literature. Specifically, in the presence of type 2 diabetes, low levels of ApoA-1 and ApoE as well as reduced catabolism of apolipoprotein B (ApoB) and overexpression of ApoC-3 are observed [49]. Enrichment of HDL particles with the oxidative moieties myeloperoxidase and serum amyloid A (SAA) is also observed under diabetic conditions [50]. Lipid composition also seems to be affected by the presence of type 2 diabetes. In particular, HDL particles are enriched in oxidised fatty acids and TAGs, possibly due to enhanced CETP activity, while CEs are mostly depleted from HDL particles [51]. As a result, the particle surface becomes neutral, thus affecting its ability to interact with plasma enzymes, such as paraoxonase 1 (PON1), lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) and lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, leading to lipid peroxide accumulation.

Lipid peroxidation is also promoted by hyperglycaemia, which in turn contributes to dysfunctional HDL, since HDL particles containing glycated PON1 exhibit defective hydrolysis of lipid peroxides [52]. Additionally, depletion of PON1-rich HDL3 particles is commonly reported in type 2 diabetes [53], alongside impairment in their antioxidant capacity. Since HDL in type 2 diabetes is unable to provide antioxidant protection to LDL, there is a failure to counteract ox-LDL-induced vasoconstriction [54]. Glycation of HDL protein components, such as ApoA-1 and PON1, also negatively affects endothelial cell survival, proliferation and migration capacity by promoting vascular inflammation and endoplasmic reticulum stress and by direct activation of pro-apoptotic pathways [4].

HDL particles from diabetic individuals promote elevated synthesis of adhesion molecules (intercellular adhesion molecule 1 [ICAM-1], VCAM-1) and therefore monocyte infiltration and vascular inflammation [55]. In such chronic inflammatory states, the HDL subpopulation consists mainly of SAA-containing HDL alongside less functional ApoA-1-HDL particles [56]. Glycated ApoA-1, in particular, has been shown to activate the NF-κB signalling pathway and therefore triggers cytokine synthesis either by its interaction with the receptor for AGEs or by upregulating SRB1-mediated ox-LDL uptake from macrophages. Furthermore, SAA enrichment also contributes to NF-kB activation and therefore exaggerated cytokine production from macrophages. In general, such dysfunctional HDL particles display impaired anti-inflammatory activity and are proven to be defective in alleviating cytokine production from macrophages and LDL-induced monocyte chemotaxis [57].

Oxidative modifications as well as glycation of ApoA-1 negatively impact its stability and compromises its interaction with ATP-binding cassette sub-family A member 1 (ABCA1), leading to impaired cholesterol efflux in most individuals with type 2 diabetes [56, 58]. Additionally, AGEs interfere with ABCA1-mediated efflux and promote cholesterol accumulation by directly downregulating ABCA1 and ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 1 (ABCG1) expression [59]. However, a small number of studies failed to demonstrate any correlation between glucose levels and cholesterol efflux capacity, implying that hyperglycaemia per se is not the only factor for defective cholesterol efflux in type 2 diabetes.

Taken together, it appears that hyperinsulinaemia and hyperglycaemia lead to reduced HDL-C levels and a deterioration in HDL functionality, via various alterations in HDL particles’ proteome and lipidome. The altered HDL composition and structure noted in type 2 diabetes promotes the progression of atherosclerosis through defective cholesterol efflux, increased oxidative stress, exaggerated inflammatory responses, vascular dysfunction and reduced anti-apoptotic activity.

Impact of HDL on type 2 diabetes

HDL levels and functionality have been implicated in glucose homeostasis mainly by four distinct mechanisms: beta cell insulin secretion; peripheral insulin sensitivity; non-insulin-dependent glucose uptake; and adipose tissue metabolic activation [60] (Fig. 1). Increased HDL-C levels are considered protective against type 2 diabetes by facilitating insulin secretion and modifying glucose uptake. In contrast, reduced HDL-C levels predispose to the development of the disease, even though low HDL-C levels alone have not been directly associated with its induction. In addition to HDL-C levels, HDL particle size has been shown to relate to the regulation of glucose homeostasis. Strikingly, large spherical HDL (HDL2) particles correlate inversely with type 2 diabetes risk and good glycaemic control [44]. In contrast, smaller TAG-rich HDL particles are possibly associated with elevated plasma glucose levels [61].

Increasing HDL-C and ApoA-1 levels seems to enhance glycaemic control by improving two key anti-atherogenic HDL features: antioxidant capacity and reverse cholesterol transport [62, 63]. Reverse cholesterol transport has been reported to facilitate insulin secretion by protecting beta cells from cholesterol-induced toxicity, stress-induced apoptosis and inflammation through inhibition of cytokine-stimulated apoptosis [64]. In line with these findings, reduced ABCA1 activity has been linked to low levels of secreted insulin due to impaired cholesterol efflux and, thus, increased intracellular cholesterol and cholesterol membrane deposition leading to cell lipotoxicity [65]. It has been demonstrated that infusion of HDL in diabetic individuals improves pancreatic beta cell function, possibly due to reduced apoptosis [66, 67]. Many other HDL-related proteins and apolipoproteins also play an important role in insulin secretion and glucose homeostasis. It has been reported that ApoA-1 enhances insulin secretion resulting in improved glucose tolerance [68, 69]. Similarly, apolipoprotein A4 (ApoA-4) was shown to boost insulin secretion in hyperglycaemic states and reduce serum glucose levels [62, 70].

Besides insulin secretion, glucose uptake by peripheral tissues is also positively affected by HDL particle functionality, as defined by its composition and its functional interactions with other factors. ApoA-1 and -2 seem to boost glucose-stimulated insulin secretion through enhanced cholesterol efflux mediated by ABCA1 [66]. More specifically, ApoA-1 is strongly associated with enhanced insulin sensitivity and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion mainly via an ABCA1–Cdc42–cAMP–protein kinase A (PKA) pathway [71,72,73,74]. Furthermore, recent data suggest that ApoA-1 as well as reconstituted discoidal HDL particles modulate skeletal muscle glucose uptake via an insulin-independent pathway involving GLUT-4 translocation [71, 75]. Additionally, it was recently shown that ApoA-1-mediated heart and skeletal muscle glucose uptake could be independent of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway [76]. The rs670 variant of the APOA1 gene has been found to result in higher HDL-C levels, enhanced insulin levels and HOMA-IR modifications while it also correlated with reduced insulin resistance [77]. Furthermore, this variant enhances insulin secretion resulting in improved glucose tolerance [68, 78].

Recent data demonstrated that ABCA1 gene variants contribute to the development of type 2 diabetes by reducing serum HDL-C levels [79, 80] and by increasing intracellular non-esterified cholesterol levels, leading to cell lipotoxicity and thus impaired pancreatic beta cell function [81,82,83,84,85]. Moreover ABCA1 gene downregulation reduces insulin-dependent Akt phosphorylation and GLUT4 translocation, affecting insulin sensitivity [46, 48]. On the contrary, dysfunctional ABCA1 has been also linked to improved secretory ability of beta cells, potentially due to increased cholesterol supply for their secretory needs [86].

The direct causative relationship between HDL structure and type 2 diabetes was investigated in a study evaluating the role of ApoA-1 and LCAT deficiency in diet-induced obesity and glucose homeostasis in mice [87]. ApoA-1 deficiency results in lack of classical ApoA-1-HDL, while LCAT deficiency results in mainly discoidal HDL particles, both of which constitute drastic changes in HDL structure and composition. Indeed, HDL from ApoA-1-deficient (Apoa1−/−) mice contained mainly ApoE, while HDL from LCAT-deficient (Lcat−/−) mice contained primarily ApoA-2; both strains displayed significantly reduced HDL-C levels [87]. The structural differences in the HDL of Apoa1−/− and Lcat−/− mice correlated with distinct metabolic abnormalities in each strain. Even though both strains developed obesity, the beta cells from only the Apoa1−/− mouse islets showed reduced capacity to secrete insulin in response to glucose stimulation. This observation was attributed to the increased rigidity of the beta cell membrane, a physicochemical property that is associated with reduced stimulation of ion channels, which are of paramount importance for insulin secretion [88]. Similarly, skeletal muscles of only the Apoa1−/− mice showed reduced glucose uptake upon insulin stimulation. Even though it is often mentioned that obesity is the cause of diabetes in individuals with the metabolic syndrome, these findings strongly suggest that HDL structure, rather than adipose tissue, is responsible for the observed glucose metabolic abnormalities.

Conclusions and future directions

Based on the current literature, a bidirectional correlation between HDL dysfunction and type 2 diabetes exists, leading to a perpetual self-feeding cycle (Fig. 1). It is increasingly evident that not all HDL disturbances are causatively associated with the development and progression of type 2 diabetes. Most recent clinical and epidemiological data indicate that an optimal range of plasma HDL-C concentrations exists in humans. Even though very high HDL-C levels appear to correlate with dysfunctional HDL, this does not necessarily preclude a substantial benefit when raising ones HDL-C from very low levels to levels within the optimal range. The notion that HDL proteome dictates its lipidome and subsequently HDL particle functionality [11] suggests that alterations in the HDL metabolic pathway have substantial influence on its properties and functions. However, the interrelation between HDL lipidome, proteome and particle functionality is a missing part of the puzzle, which remains as yet unsolved. HDL, the sleeping beauty of lipoproteins, is waiting for its prince to awake her therapeutic potential. Understanding HDL functionality and the factors affecting it in diabetic individuals remains a crucial step towards better glucose homeostasis.

Abbreviations

- ABCA1:

-

ATP-binding cassette sub-family A member 1

- ApoA-1:

-

Apolipoprotein A1

- ApoA-1-HDL:

-

ApoA-1-containing HDL

- ApoA-2:

-

Apolipoprotein A2

- ApoA-2-HDL:

-

ApoA-2-containing HDL

- ApoA-4:

-

Apolipoprotein A4

- ΑpoB:

-

Apolipoprotein B

- ApoC-3:

-

Apolipoprotein C3

- ApoC-3-HDL:

-

ApoC-3-containing HDL

- ApoE:

-

Apolipoprotein E

- ApoE-HDL:

-

ApoE-containing HDL

- CE:

-

Cholesteryl ester

- CETP:

-

Cholesteryl ester transfer protein

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association study

- HDL-C:

-

HDL-cholesterol

- LCAT:

-

Lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase

- LDL-C:

-

LDL-cholesterol

- ox-LDL:

-

Oxidised LDL

- PON1:

-

Paraoxonase 1

- SAA:

-

Serum amyloid A

- SRB1:

-

Scavenger receptor class B type 1

- TAG:

-

Triacylglycerol

- VCAM-1:

-

Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1

References

Constantinou C, Karavia EA, Xepapadaki E et al (2016) Advances in high-density lipoprotein physiology: surprises, overturns, and promises. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 310(1):E1–E14. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00429.2015

Karavia EA, Zvintzou E, Petropoulou PI, Xepapadaki E, Constantinou C, Kypreos KE (2014) HDL quality and functionality: What can proteins and genes predict? Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 12(4):521–532. https://doi.org/10.1586/14779072.2014.896741

Xepapadaki E, Zvintzou E, Kalogeropoulou C, Filou S, Kypreos KE (2020) Τhe Antioxidant Function of HDL in Atherosclerosis. Angiology 71:112–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003319719854609

Tsompanidi EM, Brinkmeier MS, Fotiadou EH, Giakoumi SM, Kypreos KE (2010) HDL biogenesis and functions: Role of HDL quality and quantity in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 208(1):3–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.05.034

Gofman JW, Glazier F, Tamplin A, Strisower B, De LO (1954) Lipoproteins, coronary heart disease, and atherosclerosis. Physiol Rev 34(3):589–607. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1954.34.3.589

Miller GJ, Miller NE (1975) Plasma-high-density-lipoprotein concentration and development of ischaemic heart-disease. Lancet 1(7897):16–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92376-4

Nofer JR, Kehrel B, Fobker M, Levkau B, Assmann G, von Eckardstein A (2002) HDL and arteriosclerosis: Beyond reverse cholesterol transport. Atherosclerosis 161(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9150(01)00651-7

Nagao M, Nakajima H, Toh R, Hirata KI, Ishida T (2018) Cardioprotective effects of high-density lipoprotein beyond its anti-atherogenic action. J Atheroscler Thromb 25:985–993. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.RV17025

Zvintzou E, Skroubis G, Chroni A et al (2014) Effects of bariatric surgery on HDL structure and functionality: Results from a prospective trial. J Clin Lipidol 8(4):408–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2014.05.001

Kavo AE, Rallidis LS, Sakellaropoulos GC et al (2012) Qualitative characteristics of HDL in young patients of an acute myocardial infarction. Atheroscler 220(1):257–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.10.017

Filou S, Lhomme M, Karavia EA et al (2016) Distinct Roles of Apolipoproteins A1 and e in the Modulation of High-Density Lipoprotein Composition and Function. Biochemistry 55(27):3752–3762. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00389

Zvintzou E, Lhomme M, Chasapi S et al (2017) Pleiotropic effects of apolipoprotein C3 on HDL functionality and adipose tissue metabolic activity. J Lipid Res 58(9):1869–1883. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M077925

Zvintzou E, Xepapadaki E, Kalogeropoulou C, Filou S, Kypreos KE (2020) Pleiotropic effects of apolipoprotein A-II on high-density lipoprotein functionality, adipose tissue metabolic activity and plasma glucose homeostasis. J Biomed Res 34(1):14–26. https://doi.org/10.7555/JBR.33.20190048

Voight BF, Peloso GM, Orho-Melander M et al (2012) Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: A mendelian randomisation study. Lancet 380(9841):572–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60312-2

Haase CL, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Ali Qayyum A, Schou J, Nordestgaard BG, Frikke-Schmidt R (2012) LCAT, HDL cholesterol and ischemic cardiovascular disease: A mendelian randomization study of HDL cholesterol in 54,500 individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97(2):248–256. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-1846

Fall T, Xie W, Poon W et al (2015) Using genetic variants to assess the relationship between circulating lipids and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 64(7):2676–2684. https://doi.org/10.2337/db14-1710

Swerdlow DI, Preiss D, Kuchenbaecker KB et al (2015) HMG-coenzyme A reductase inhibition, type 2 diabetes, and bodyweight: Evidence from genetic analysis and randomised trials. Lancet 385(9965):351–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61183-1

Swerdlow DI, Sattar N (2015) Blood lipids and type 2 diabetes risk: Can genetics help untangle the web? Diabetes 64:2344–2345. https://doi.org/10.2337/db15-0458

Thomas DG, Wei Y, Tall AR (2021) Lipid and metabolic syndrome traits in coronary artery disease: A Mendelian randomization study. J Lipid Res 62:100044. https://doi.org/10.1194/JLR.P120001000

Bowe B, Xie Y, Xian H, Balasubramanian S, Zayed MA, Al-Aly Z (2016) High density lipoprotein cholesterol and the risk of all-cause mortality among U.S. veterans. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11(10):1784–1793. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.00730116

Ko DT, Alter DA, Guo H et al (2016) High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Cause-Specific Mortality in Individuals Without Previous Cardiovascular Conditions: The CANHEART Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 68(19):2073–2083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.038

Madsen CM, Varbo A, Nordestgaard BG (2017) Extreme high high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is paradoxically associated with high mortality inmen and women: Two prospective cohort studies. Eur Heart J 38(32):2478–2486. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx163

Kannel WB (1983) High-density lipoproteins: Epidemiologic profile and risks of coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 52(4):9–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(83)90649-5

Kypreos KE, Bitzur R, Karavia EA, Xepapadaki E, Panayiotakopoulos G, Constantinou C (2019) Pharmacological Management of Dyslipidemia in Atherosclerosis: Limitations, Challenges, and New Therapeutic Opportunities. Angiology 70(3):197–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003319718779533

Bowman L, Hopewell JC, Chen F et al (2018) Effects of Anacetrapib in Patients With Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease. J Vasc Surg 67(1):356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2017.11.029

Zeman M, Vecka M, Perlík F et al (2015) Niacin in the treatment of hyperlipidemias in light of new clinical trials: Has niacin lost its place? Med Sci Monit 21:2156–2162. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.893619

Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T et al (2011) Niacin in Patients with Low HDL Cholesterol Levels Receiving Intensive Statin Therapy. N Engl J Med 365(24):2255–2267. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1107579

Landray MJ, Haynes R, Hopewell JC et al (2014) Effects of Extended-Release Niacin with Laropiprant in High-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med 371(3):203–212. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1300955

Tardy C, Goffinet M, Boubekeur N et al (2014) CER-001, a HDL-mimetic, stimulates the reverse lipid transport and atherosclerosis regression in high cholesterol diet-fed LDL-receptor deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 232(1):110–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.10.018

Nicholls SJ, Andrews J, Kastelein JJP et al (2018) Effect of serial infusions of CER-001, a pre-β High-density lipoprotein mimetic, on coronary atherosclerosis in patients following acute coronary syndromes in the CER-001 atherosclerosis regression acute coronary syndrome trial: A randomized clinical tria. JAMA Cardiol 3(9):815–822. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2018.2121

Shaw JA, Bobik A, Murphy A et al (2008) Infusion of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein leads to acute changes in human atherosclerotic plaque. Circ Res 103(10):1084–1091. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182063

Tardif JC, Grégoire J, L’Allier PL et al (2007) Effects of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein infusions on coronary atherosclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc 297(15):1675–1682. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.15.jpc70004

Gibson CM, Korjian S, Tricoci P et al (2016) Safety and Tolerability of CSL112, a Reconstituted, Infusible, Plasma-Derived Apolipoprotein A-I, after Acute Myocardial Infarction: The AEGIS-I Trial (ApoA-I Event Reducing in Ischemic Syndromes I). Circulation 134(24):1918–1930. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025687

Diditchenko S, Gille A, Pragst I et al (2013) Novel formulation of a reconstituted high-density lipoprotein (CSL112) dramatically enhances ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33(9):2202–2211. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301981

ClinicalTrials.gov (2018) Identifier NCT03473223, Study to investigate CSL112 in subjects with acute coronary syndrome (AEGIS-II). Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03473223. Accessed 8 June 2021

D’Souza W, Stonik JA, Murphy A et al (2010) Structure/function relationships of apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptides: Implications for antiatherogenic activities of high-density lipoprotein. Circ Res 107(2):217–227. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.216507

Van Lenten BJ, Wagner AC, Jung CL et al (2008) Anti-inflammatory apoA-I-mimetic peptides bind oxidized lipids with much higher affinity than human apoA-I. J Lipid Res 49(11):2302–2311. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M800075-JLR200

Navab M, Hama S, Hough G, Reddy S, Anantharamaiah M, Fogelman A (2003) Oral administration of the apoA-I mimetic peptide D-4F causes the rapid formation and clearance of small anti-inflammatory HDL-like particles in mice. Circ 108(17):232

Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Reddy ST et al (2004) Oral D-4F causes formation of pre-beta high-density lipoprotein and improves high-density lipoprotein-mediated cholesterol efflux and reverse cholesterol transport from macrophages in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Circulation 109(25):3215–3220. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000134275.90823.87

Dunbar RL, Movva R, Bloedon LAT et al (2017) Oral Apolipoprotein A-I Mimetic D-4F Lowers HDL-Inflammatory Index in High-Risk Patients: A First-in-Human Multiple-Dose, Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Transl Sci 10(6):455–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.12487

Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P et al (2019) Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 157:107843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843

Filippatos T, Tsimihodimos V, Pappa E, Elisaf M (2017) Pathophysiology of Diabetic Dyslipidaemia. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 15(6):886–899. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570161115666170201105425

Mora S, Otvos JD, Rosenson RS, Pradhan A, Buring JE, Ridker PM (2010) Lipoprotein particle size and concentration by nuclear magnetic resonance and incident type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes 59(5):1153–1160. https://doi.org/10.2337/db09-1114

Tabara Y, Arai H, Hirao Y et al (2017) Different inverse association of large high-density lipoprotein subclasses with exacerbation of insulin resistance and incidence of type 2 diabetes: The Nagahama study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 127:123–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.018

Koo SH, Dutcher AK, Towle HC (2001) Glucose and insulin function through two distinct transcription factors to stimulate expression of lipogenic enzyme genes in liver. JBiolChem 276(12):9437–9445

Rashid S, Watanabe T, Sakaue T, Lewis GF (2003) Mechanisms of HDL lowering in insulin resistant, hypertriglyceridemic states: The combined effect of HDL triglyceride enrichment and elevated hepatic lipase activity. Clin Biochem 36:421–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-9120(03)00078-X

Thuahnai ST, Lund-Katz S, Dhanasekaran P et al (2004) Scavenger receptor class B type I-mediated cholesteryl ester-selective uptake and efflux of unesterified cholesterol: Influence of high density lipoprotein size and structure. J Biol Chem 279(13):12448–12455. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M311718200

Sparks DL, Davidson WS, Lund-Katz S, Phillips MC (1995) Effects of the neutral lipid content of high density lipoprotein on apolipoprotein A-I structure and particle stability. J Biol Chem 270(45):26910–26917. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.270.45.26910

Zhang P, Gao J, Pu C, Zhang Y (2017) Apolipoprotein status in type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications (Review). Mol Med Rep 16:9279–9286. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2017.7831

Kheniser KG, Osme A, Kim C, Ilchenko S, Kasumov T, Kashyap SR (2020) Temporal Dynamics of High-Density Lipoprotein Proteome in Diet-Controlled Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes. Biomolecules 10(4):520. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10040520

Morgantini C, Meriwether D, Baldi S et al (2014) HDL lipid composition is profoundly altered in patients with type 2 diabetes and atherosclerotic vascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 24(6):594–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2013.12.011

Mastorikou M, Mackness B, Liu Y, Mackness M (2008) Glycation of paraoxonase-1 inhibits its activity and impairs the ability of high-density lipoprotein to metabolize membrane lipid hydroperoxides. Diabet Med 25(9):1049–1055. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02546.x

Kotur-Stevuljević J, Vekić J, Stefanović A et al (2020) Paraoxonase 1 and atherosclerosis-related diseases. BioFactors 46:193–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/biof.1549

Perségol L, Vergès B, Foissac M, Gambert P, Duvillard L (2006) Inability of HDL from type 2 diabetic patients to counteract the inhibitory effect of oxidised LDL on endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Diabetologia 49(6):1380–1386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-006-0244-1

Lemmers RFH, van Hoek M, Lieverse AG, Verhoeven AJM, Sijbrands EJG, Mulder MT (2017) The anti-inflammatory function of high-density lipoprotein in type II diabetes: A systematic review. J Clin Lipidol 11(3):712–724.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2017.03.013

Srivastava RAK (2018) Dysfunctional HDL in diabetes mellitus and its role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Mol Cell Biochem 440:167–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-017-3165-z

Estruch M, Miñambres I, Sanchez-Quesada JL et al (2017) Increased inflammatory effect of electronegative LDL and decreased protection by HDL in type 2 diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis 265:292–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.07.015

Shao B, Tang C, Heinecke JW, Oram JF (2010) Oxidation of apolipoprotein A-I by myeloperoxidase impairs the initial interactions with ABCA1 required for signaling and cholesterol export. J Lipid Res 51(7):1849–1858. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M004085

Tsujita M, Hossain MA, Lu R, Tsuboi T, Okumura-Noji K, Yokoyama S (2017) Exposure to high glucose concentration decreases cell surface abca1 and hdl biogenesis in hepatocytes. J Atheroscler Thromb 24(11):1132–1149. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.39156

Drew BG, Rye KA, Duffy SJ, Barter P, Kingwell BA (2012) The emerging role of HDL in glucose metabolism. NatRevEndocrinol 8(4):237–245

Liu J, van Klinken JB, Semiz S et al (2017) A Mendelian Randomization Study of Metabolite Profiles, Fasting Glucose, and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 66(11):2915–2926. https://doi.org/10.2337/db17-0199

Rye K-A, Barter PJ, Cochran BJ (2016) Apolipoprotein A-I interactions with insulin secretion and production. Curr Opin Lipidol 27(1):8–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOL.0000000000000253

Calkin AC, Drew BG, Ono A et al (2009) Reconstituted high-density lipoprotein attenuates platelet function in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus by promoting cholesterol efflux. Circulation 120(21):2095–2104. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.870709

Kruit JK, Brunham LR, Verchere CB, Hayden MR (2010) HDL and LDL cholesterol significantly influence beta-cell function in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Lipidol 21(3):178–185

Kruit JK, Kremer PHC, Dai L et al (2010) Cholesterol efflux via ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) and cholesterol uptake via the LDL receptor influences cholesterol-induced impairment of beta cell function in mice. Diabetologia 53(6):1110–1119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-010-1691-2

Fryirs MA, Barter PJ, Appavoo M et al (2010) Effects of high-density lipoproteins on pancreatic beta-cell insulin secretion. Arter 30(8):1642–1648

Von EA, Widmann C (2014) High-density lipoprotein, beta cells, and diabetes. Cardiovasc 103(3):384–394

Domingo-Espín J, Lindahl M, Nilsson-Wolanin O, Cushman SW, Stenkula KG, Lagerstedt JO (2016) Dual actions of apolipoprotein A-I on glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and insulin-independent peripheral tissue glucose uptake lead to increased heart and skeletal muscle glucose disposal. Diabetes 65(7):1838–1848. https://doi.org/10.2337/db15-1493

Matsumura K, Tamasawa N, Daimon M (2018) Possible insulinotropic action of apolipoprotein A-I through the ABCA1/Cdc42/cAMP/PKA pathway in MIN6 cells. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 9(OCT):645. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00645

Wang F, Kohan AB, Kindel TL et al (2012) Apolipoprotein A-IV improves glucose homeostasis by enhancing insulin secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109(24):9641–9646. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1201433109

Dalla-Riva J, Stenkula KG, Petrlova J, Lagerstedt JO (2013) Discoidal HDL and apoA-I-derived peptides improve glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. J Lipid Res 54(5):1275–1282

Song P, Kwon Y, Yea K et al (2015) Apolipoprotein a1 increases mitochondrial biogenesis through AMP-activated protein kinase. Cell Signal 27(9):1873–1881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.05.003

Stenkula KG, Lindahl M, Petrlova J et al (2014) Single injections of apoA-I acutely improve in vivo glucose tolerance in insulin-resistant mice. Diabetol 57(4):797–800. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-014-3162-7

Manandhar B, Cochran BJ, Rye KA (2020) Role of High-Density Lipoproteins in Cholesterol Homeostasis and Glycemic Control. J Am Heart Assoc 9(1):e013531. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.013531

Tang S, Tabet F, Cochran BJ et al (2019) Apolipoprotein A-I enhances insulin-dependent and insulin-independent glucose uptake by skeletal muscle. Sci Rep 9(1):1350. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38014-3

Fritzen AM, Domingo-Espín J, Lundsgaard AM et al (2020) ApoA-1 improves glucose tolerance by increasing glucose uptake into heart and skeletal muscle independently of AMPKα2. Mol Metab 35:100949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2020.01.013

de Luis D, Izaola O, Primo D, Aller R (2019) Role of rs670 variant of APOA1 gene on metabolic response after a high fat vs. a low fat hypocaloric diets in obese human subjects. J Diabetes Complicat 33(3):249–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2018.10.015

Edmunds SJ, Liébana-García R, Nilsson O et al (2019) ApoAI-derived peptide increases glucose tolerance and prevents formation of atherosclerosis in mice. Diabetologia 62(7):1257–1267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-019-4877-2

Ochoa-Guzmán A, Moreno-Macías H, Guillén-Quintero D et al (2020) R230C but not − 565C/T variant of the ABCA1 gene is associated with type 2 diabetes in Mexicans through an effect on lowering HDL-cholesterol levels. J Endocrinol Investig 43(8):1061–1071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-020-01187-8

Gamboa-Meléndez MA, Galindo-Gómez C, Juárez-Martínez L et al (2015) Novel Association of the R230C Variant of the ABCA1 Gene with High Triglyceride Levels and Low High-density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels in Mexican School-age Children with High Prevalence of Obesity. Arch Med Res 46(6):495–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcmed.2015.07.008

de HW, Karasinska JM, Ruddle P, Hayden MR (2014) Hepatic ABCA1 expression improves beta-cell function and glucose tolerance. Diabetes 63(12):4076–4082

Brunham LR, Kruit JK, Pape TD et al (2007) Beta-cell ABCA1 influences insulin secretion, glucose homeostasis and response to thiazolidinedione treatment. Nat Med 13(3):340–347

Kruit JK, Wijesekara N, Fox JE et al (2011) Islet cholesterol accumulation due to loss of ABCA1 leads to impaired exocytosis of insulin granules. Diabetes 60(12):3186–3196. https://doi.org/10.2337/db11-0081

Kruit JK, Wijesekara N, Westwell-Roper C et al (2012) Loss of both ABCA1 and ABCG1 results in increased disturbances in islet sterol homeostasis, inflammation, and impaired beta-cell function. Diabetes 61(3):659–664. https://doi.org/10.2337/db11-1341

Wijesekara N, Zhang LH, Kang MH et al (2012) miR-33a modulates ABCA1 expression, cholesterol accumulation, and insulin secretion in pancreatic islets. Diabetes 61(3):653–658. https://doi.org/10.2337/db11-0944

Rickels MR, Goeser ES, Fuller C et al (2015) Loss-of-function mutations in ABCA1 and enhanced β-cell secretory capacity in young adults. Diabetes 64(1):193–199. https://doi.org/10.2337/db14-0436

Xepapadaki E, Maulucci G, Constantinou C et al (2019) Impact of apolipoprotein A1- or lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase-deficiency on white adipose tissue metabolic activity and glucose homeostasis in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Basis Dis 1865(6):1351–1360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2019.02.003

Gleason MM, Medow MS, Tulenko TN (1991) Excess membrane cholesterol alters calcium movements, cytosolic calcium levels, and membrane fluidity in arterial smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 69(1):216–227. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.69.1.216

Authors’ relationships and activities

The authors declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were responsible for drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM

(PPTX 199 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xepapadaki, E., Nikdima, I., Sagiadinou, E.C. et al. HDL and type 2 diabetes: the chicken or the egg?. Diabetologia 64, 1917–1926 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05509-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05509-0