Abstract

This paper examines the efficiency of destination-and origin-based consumption taxes, in the presence of consumption generated perfect cross-border pollution spillovers, when tax revenue either finances public pollution abatement or it is lump-sum distributed. When consumption tax revenue finances the provision of public pollution abatement and regions have identical and quasi-linear preferences then, the non-cooperative equilibrium origin-based consumption taxes are efficient, while the destination-based consumption taxes are inefficiently low. When, however, consumption tax revenue is lump-sum distributed, then, the destination-based tax principle leads to inefficiently low taxes, while the origin-based tax principle leads either to inefficiently high or low taxes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA, 2014) reports that in the US, about \(40\%\) of greenhouse gases are attributed to residential activity. In a highly influential study, Jambeck et al. (2015) estimate the mass of land-based plastic waste entering the ocean and calculate that 275 million metric tons (MT) of plastic waste was generated in 192 coastal countries in 2010, with 4.8 to 12.7 million MT entering the ocean. Other examples of goods generating tailpipe pollution are fuels, tobacco products, pesticides, and solvents.

For example, OECD (2014) pp. 135-160, reports: Per litre total taxation (VAT + excise) on premium unleaded gasoline: Australia 0.51, Canada 0.39, Germany 1.20, the U.K. 1.25, the U.S. 0.14.

Considering the specific case of pollution from motor vehicles, Adamou et al. (2014) attest that welfare can increase when appropriate taxes yield positive revenues at the expense of consumer and producer surplus.

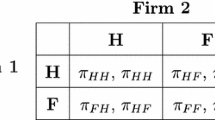

As noted in OECD (2014), p. 24, “...The key economic difference between the two principles is that the destination principle places all firms competing in a jurisdiction on an even footing whereas the origin principle places consumers in different jurisdictions on even footing...”.

A number of studies consider the environmental and welfare implications of consumption or emission taxes in the presence of local or cross-border consumption generated pollution, e.g., Chao et al. (2012), Michael and Hatzipanayotou (2013), Tsakiris et al. (2019). Other studies, using different analytical frameworks, examine the issue of efficiency of different policies in the presence of local or transboundary production generated pollution, e.g., Silva and Caplan (1997), Chen and Woodland (2013), Angelopoulos et al. (2017), Montagna et al. (2020).

Following examples such as the EU, the US, and Canada, Home and Foreign can be viewed either as two countries constituting an economic union vis-a-vis the ROW, or as two regions of a federal economy vis-a-vis the ROW.

This pattern of production specialization implies that the economic union is a net exporter of goods “\(1\)” and “\(2\)” to ROW and a net importer of the numeraire and is commonly used in the relevant literature of international commodity taxation, e.g., Haufler, 1994; Haufler and Pflüger, 2007; Moriconi and Sato, 2009.

The production of goods can be either a polluting or a clean activity. Note that we assume that Home and Foreign are small open economies where producer prices are not affected by consumption taxes. Therefore, changes in consumption taxes do not affect production and production generated emissions. Furthermore, in the present context, even if production was a polluting activity and production taxes were levied to control for production emissions, the results still would not change. Again, this is because of the assumption of small open economies in world commodity markets. Changes in consumption taxes do not affect production prices, production and revenue from taxes on production generated emissions.

In our context, pollution emissions do not affect factor productivity and production possibilities. For such an interesting extension, e.g., Kotsogiannis and Woodland (2013).

All subscripts of the expenditure function denote partial derivatives, e.g., \(e_{q_{1}q_{1}}=\partial e_{q_{1}}/\partial q_{1}\). The use of the duality approach via the GDP and minimum expenditure functions presents a great deal of algebraic simplicity and clarity of the results.

A utility function compatible with these assumptions is an additively separable function, e.g., \(U\left( c_{0},c_{1},c_{2},r\right) =V\left( c_{0},c_{1},c_{2}\right) -f\left( r\right)\). We assume that the sub-utility \(V\left( c_{0},c_{1},c_{2}\right) =c_{0}+\nu (c_{1},c_{2})\) is quasi-linear and increasing in consumption, with income effects falling on the numeraire commodity 0. f(r) is increasing and convex in r. Because of the above specification, the expenditure function \(e\left( .\right)\) entails complete separability between consumption and pollution, i.e., \(e_{q_{i}r}=0\), e.g., Bandyopadhyay et al., 2013, ft. 15. That is, the relative demands are independent of the environmental damage. For the properties of the expenditure function, e.g., Kreickemeier (2005), Palivos and Tsakiris (2011), and Antoniou et al. (2019).

Qualitatively similar results can be obtained using general utility functions where income effects on all commodities are not zero, assuming that regions are symmetric. The analysis of this case is omitted since it is mathematically complex without providing significant insights to the results.

The assumption of an untaxed numeraire commodity is common in the international commodity taxation literature, since all tax systems exempt from taxation a share of national product, e.g., Moriconi and Sato (2009).

Alternative specifications of the government budget constraints can be easily introduced with the present analytical apparatus, e.g., the tax revenue partly finances the purchases of g and \(g^{*}\) and partly is either lump-sum returned to the representative household or it finances the purchases of other, interregional or local, public consumption goods. These specifications only raise additional algebraic complexities without contributing to the importance and clarity of the results. Furthermore, one may consider the case where public pollution abatement consists of purchases of the numeraire commodity. In this case, the unit price of \(g\left( g^{*}\right)\) is the fixed price of the numeraire good.

A more general formulation for the levels of pollution r and \(r^{*}\) could be that, \(r=\left[ e_{q_{1}}\left( .\right) +e_{q_{2}}\left( .\right) -g\right] +\theta \left[ e_{q_{1}^{*}}^{*}\left( .\right) +e_{q_{2}^{*}}^{*}\left( .\right) -g^{*}\right]\) and \(r^{*}= \left[ e_{q_{1}^{*}}^{*}\left( .\right) +e_{q_{2}^{*}}^{*}\left( .\right) -g^{*}\right] +\theta ^{*}\left[ e_{q_{1}}\left( .\right) +e_{q_{2}}\left( .\right) -g\right]\). \(0\le \theta \le 1\) and \(0\le \theta ^{*}\le 1\) denote the rates of cross-border pollution from Foreign to Home and vice-versa, with \(\theta =\theta ^{*}=0\) denoting local pollution and \(\theta =\theta ^{*}=1\) denoting perfect cross-border pollution.

In Haufler (1994), the two union countries apply the origin principle of commodity taxation for their mutual trade, and the destination principle for the trade between each of them and the ROW.

From Eq. (7), \(e_{r}^{-1}p_{g}e_{u}\frac{du}{ dt_{o}}\mid _{N}=0\Longrightarrow -\left( p_{g}-t_{o}\right) E_{q_{1}q_{1}}-\left( p_{g}-t_{o}^{*}\right) E_{q_{2}q_{1}}=-e_{r}^{-1}\left( e_{r}-p_{g}\right) e_{q_{1}}-e_{q_{1}^{*}}^{*}\). Substituting this expression into the expression for \(e_{r^{*}}^{*^{-1}}p_{g}e_{u}^{*}\frac{du^{*}}{dt_{o}}\), after some algebra, we arrive at the result in Eq. (10).

Since at Nash equilibrium \(e_{r}^{-1}p_{g}e_{u}\frac{du}{dt_{o}}\mid _{N}=0\) and \(e_{r^{*}}^{*^{-1}}p_{g}e_{u}^{*}\frac{du^{*}}{ dt_{o}^{*}}\mid _{N}=0,\) then from Eq. (5) we get that at Nash \((dr^{*}/dt_{o})=(-e_{q_{1}}/e_{r})<0.\)

From the properties of the expenditure function, we know that \(q_{_{0}}e_{q_{1}q_{0}}+q_{_{1}}e_{q_{1}q_{1}}+q_{_{2}}e_{q_{1}q_{2}}=0\), and \(e_{q_{i}q_{j}}=e_{q_{j}q_{i}}\). Since producer prices of both goods equal 1 and consumption taxes are the same, we have \(q_{_{1}}=q_{_{2}}=q.\) Thus, \(q_{_{0}}e_{q_{1}q_{0}}+q(e_{q_{1}q_{1}}+e_{q_{1}q_{2}})=q_{_{0}}e_{q_{1}q_{0}}+qZ_{q_{1}}=0.\) Similarly, \(q_{_{0}}e_{q_{2}q_{0}}+qZ_{q_{2}}=0\). Thus, \(q(Z_{q_{1}}+Z_{q_{2}})=-q_{_{0}}(e_{q_{0}q_{1}}+e_{q_{0}q_{2}})\), which can be written as \(q(Z_{q_{1}}+Z_{q_{2}})=\) \(\frac{q_{_{0}}}{q} (q_{_{0}}e_{q_{0}q_{0}})\) \(<0\).

From Eq. (12), we have \(e_{u}\frac{du}{dt_{d}}\mid _{N}=0\Rightarrow \frac{dr}{dt_{d}}=-e_{r}^{-1}\left( e_{q_{1}}+e_{q_{2}}\right)\), and \(e_{u^{*}}^{*}\frac{du^{*}}{ dt_{d}}=-e_{r^{*}}^{*}\frac{dr^{*}}{dt_{d}}\). Since by Eq. (11) \(\frac{dr}{dt_{d}}=\frac{ dr^{*}}{dt_{d}}\), then at Nash equilibrium we obtain Eq. (16).

Using Eqs. (27) and (28) in the presence of consumption generated cross-border pollution, the cooperative consumption taxes under the origin principle of taxation are given by Eq. (34). The cooperative taxes under the origin-based taxation principle are the same as those under the destination-based principle, since the two regimes are equivalent under cooperative taxation.

For example, if commodities 1 and 2 are complements, i.e., \(E_{q_{2}q_{1}}<0\), a higher \(t_{o}\) by Home also reduces aggregate consumption of commodity 2, thus Foreign’s consumption tax revenue and welfare.

Haufler and Pflüger (2007), without consumption pollution, demonstrate that the sum \(-e_{q_{1}^{*}}^{*}-E_{q_{2}q_{2}}^{-1}E_{q_{2}q_{1}}e_{q_{2}},\) is negative.

The assumption of a zero tax on the quantities consumed of the numeraire good is consistent with tax practices in many tax systems which exempt from taxation a list of goods and services. This exemption is applied not only to locally produced goods but also to imports at the same rates according to the rules of World Trade Organization (WTO). Another common feature of many tax systems is the reduced and the super-reduced rates of a list of commodities and services.

The efficiency of the origin-based consumption tax remains unaffected even if in each region the exported polluting good is taxed under the origin principle while the imported polluting one is taxed under the destination principle. This, however, implies double taxation on the good imported by each region.

The issue of the provision of international or interregional public goods and destination and origin-based commodity taxes has been examined in models of international or interregional tax harmonization, e.g., Karakosta et al. (2014). This, however, is a distinct literature not related to the present study.

That is, public sector activities which entails other types of positive interregional externalities, e.g., measures for the prevention of infectious diseases, or adapting measures against climatic changes.

This is an assumption for analytical simplicity, quite prevalent in the relevant literature, e.g., Bjorvatn and Schjelderup (2002). Alternatively, it is easy to model the case where each region finances the provision of a different interregional public good, enjoyed, however, by consumers in both regions.

The total differentiation of these two equations yields \(e_{u}du=-e_{r}dr+ \left( e_{q_{1}^{*}}^{*}+t_{o}E_{q_{1}q_{1}}\right) dt_{o}+\left( -e_{q_{2}}+t_{o}E_{q_{1}q_{2}}\right) dt_{o}^{*}\), and \(dr=\left( E_{q_{1}q_{1}}+E_{q_{2}q_{1}}\right) dt_{o}+\left( E_{q_{2}q_{2}}+E_{q_{1}q_{2}}\right) dt_{o}^{*}\). Substituting the expression for dr into that for du yields Eq. (27). Similar calculations apply for the derivations of \(e_{u^{*}}^{*}du^{*}\) and \(dr^{*}\).

References

Adamou, A., Clerides, S., & Zachariadis, T. (2014). Welfare implications of car feebates: A simulation analysis. Economic Journal, 124, F420–F443.

Angelopoulos, K., Economides, G., & Philippopoulos, A. (2017). Environmental public good provision under robust decision making. Oxford Economic Papers, 69, 118–142.

Antoniou, F., Hatzipanayotou, P., & Tsakiris, N. (2019). Destination vs. origin-based Commodity Taxation in Large Open Economies with Unemployment. Economica, 86, 67–86.

Antoniou, F., & Strausz, R. (2017). Feed-in subsidies, taxation, and inefficient entry. Environmental and Resource Economics, 67, 925–940.

Bandyopadhyay, S., Bhaumik, S., & Wall, H. J. (2013). Biofuel Subsidies and International Trade. Economics & Politics, 25, 181–199.

Bjorvatn, K., & Schjelderup, G. (2002). Tax competition and international public goods. International Tax and Public Finance, 9, 111–120.

Chao, C.-C., Laffargue, J.-P., & Sgro, P. (2012). Tariff and environmental policies with product standards. Canadian Journal of Economics, 45, 978–995.

Chao, C.-C., & Yu, E. S. H. (2015). Environmental impacts of tariff and tax reforms under origin and destination principles. Pacific Economic Review, 20, 310–322.

Chen, X., & Woodland, A. (2013). International trade and climate change. International Tax and Public Finance, 20, 381–413.

COM. (2011). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and Social Committee. On the Future of VAT Towards a Simpler, More Robust and Efficient VAT System Tailored to the Single Market. European Commission, December 2011, Retrieved June 2021: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52011DC0851&from=EN.

Cremer, H., & Gahvari, F. (2006). Which border taxes? Origin and destination regimes with fiscal competition in output and emission taxes. Journal of Public Economics, 90, 2121–2142.

Davies, R. B., & Paz, L. S. (2011). Tariffs versus VAT in the presence of heterogeneous firms and an informal sector. International Tax and Public Finance, 18, 533–554.

EPA. (2014). Sources of greenhouse emissions. Retrieved June 2021: http://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions.

Esteller-Moré, A., Galmarini, U., & Rizzo, L. (2012). Vertical tax competition and consumption externalities in a federation with lobbying. Journal of Public Economics, 96, 295–305.

Fullerton, D., & West, S. (2002). Can taxes on cars and on gasoline mimic an unavailable tax on emissions? Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 43, 135–157.

Hadjiyiannis, C., Hatzipanayotou, P., & Michael, M. S. (2013). Competition for environmental aid and aid fungibility. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 65, 1–11.

Haufler, A. (1994). Unilateral tax reform under the restricted origin principle. European Journal of Political Economy, 10, 511–527.

Haufler, A., & Pflüger, M. (2007). International oligopoly and the taxation of commerce with revenue-constrained governments. Economica, 74, 451–473.

Holladay, J.S. (2008). Pollution from consumption and the trade and environment debate, Working Paper No. 2008-4. University of Colorado Department of Economics Center for Economic Analysis.

Hu, B., & McKitrick, R. (2016). Decomposing the environmental effects of trade liberalization: The case of consumption-generated pollution. Environmental and Resource Economics, 64, 205–223.

Jambeck, J. R., Geyer, R., & Wilcox, C. (2015). Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science, 347, 768–771.

Karakosta, O., Kotsogiannis, C., & Lopez-Garcia, M.-A. (2014). Indirect tax harmonization and global public goods. International Tax and Public Finance, 21, 29–49.

Keen, M., & Lahiri, S. (1998). The comparison between destination and origin principles under imperfect competition. Journal of International Economics, 45, 323–350.

Keen, M., Lahiri, S., & Raimondos-Møller, P. (2002). Tax principles and tax harmonization under imperfect competition: A cautionary example. European Economic Review, 46, 1559–1568.

Keen, M., & Wildasin, D. (2004). Pareto-efficient international taxation. American Economic Review, 94, 259–275.

Kotsogiannis, C., & Lopez-Garcia, M-A. (2007). Imperfect competition, indirect tax harmonization and public goods. International Tax and Public Finance, 14, 135–149.

Kotsogiannis, C., & Woodland, A. (2013). Climate and international trade policies when emissions affect production possibilities. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 66, 166–184.

Kreickemeier, U. (2005). Unemployment and the welfare effects of trade policy. Canadian Journal of Economics, 38, 194–210.

Linster, M., & Zegel, F. (2007). Pollution abatement and control expenditure in OECD countries, Discussion Paper. ENV/EPOC/SE (March 2007) 1. Paris: OECD.

Lockwood, B. (2001). Tax competition and tax co-ordination under destination and origin principles: a synthesis. Journal of Public Economics, 81, 279–319.

Martin, R., Muüls, M., de Preux, L. B., & Wagner, U. J. (2014). Industry compensation under relocation risk: A firm-level analysis of the EU emissions trading scheme. American Economic Review, 104, 2482–2508.

Michael, M. S., & Hatzipanayotou, P. (2013). Pollution and reforms of domestic and trade taxes towards uniformity. International Tax and Public Finance, 20, 753–768.

Mintz, J., & Tulkens, H. (1986). Commodity tax competition between member states of a federation: equilibrium and efficiency. Journal of Public Economics, 29, 133–172.

Montagna, C., Pinto, A. N., & Vlassis, N. (2020). Welfare and trade effects of international environmental agreements. Environmental and Resource Economics, 76, 331–345.

Moriconi, S., Picard, P. M., & Zanaj, S. (2019). Commodity taxation and regulatory competition. International Tax and Public Finance, 26, 919–965.

Moriconi, S., & Sato, Y. (2009). International commodity taxation in the presence of unemployment. Journal of Public Economics, 93, 939–949.

Ng, Y. K. (2008). Environmentally responsible happy nation index: Towards an internationally acceptable national success indicator. Social Indicators Research, 85, 425–446.

Nimubona, A.-D., & Rus, H. A. (2015). Green technology transfers and border tax adjustments. Environmental and Resource Economics, 62, 189–206.

OECD. (2014). Consumption Tax Trends 2014: VAT/GST and Excise Rates, Trends and Policy Issues, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Palivos, T., & Tsakiris, N. (2011). Trade and tax reforms in a cash-in-advance economy. Southern Economic Journal, 77, 1014–1032.

Pantelaiou, I., Hatzipanayotou, P., Konstantinou, P., & Xepapadeas, A. (2020). Can cleaner environment promote international trade? Environmental policies as export promoting mechanisms. Environmental and Resource Economics, 75, 809–833.

Silva, E. C. D., & Caplan, A. J. (1997). Transboundary pollution control in federal systems. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 34, 173–186.

Silva, E. C. D., & Yamaguchi, C. (2010). Interregional competition, spillovers and attachment in a federation. Journal of Urban Economics, 67, 219–225.

Vella, E., Dioikitopoulos, E., & Kalyvitis, S. (2015). Green spending reforms, growth, and welfare with endogenous subjective discounting. Macroeconomic Dynamics, 19, 1240–1260.

Tsakiris, N., Hatzipanayotou, P., & Michael, M. S. (2019). Border tax adjustments and tariff-tax reforms with consumption pollution. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 21, 1107–1125.

Vlassis, N. (2013). The welfare consequences of pollution-tax harmonization. Environmental and Resource Economics, 56, 227–238.

Welsch, H. (2006). Environment and happiness: Valuation of air pollution using life satisfaction data. Ecological Economics, 58, 801–813.

Zhao, H., Geng, G., Zhang, Q., et al. (2019). Inequality of household consumption and air pollution-related deaths in China. Nature Communications, 10, 4337.

Acknowledgements

The authors graciously acknowledge the constructive comments and suggestions by the Editor and two anonymous referees of the Journal, C. Kotsogiannis, A. Litina, A. Philippopoulos, participants in Asian Meetings of the Econometrics Society (AMES) Kyoto-Japan and 22nd Annual Conference EAERE Zurich-Switzerland. The authors remain responsible for any shortcomings of the paper. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Consumption pollution without public pollution abatement: Origin-based consumption taxes

Totally differentiating Eqs. (18) and (17) yields:Footnote 35

Sufficient, but not necessary conditions, for a higher origin-based consumption tax to improve a region’s own welfare are that: (i) the consumption tax is smaller than the marginal environmental damage of pollution in the region, i.e., \(\left( -e_{r}+t_{o}\right) <0\) and \(\left( -e_{r^{*}}^{*}+t_{o}^{*}\right) <0\), and (ii) commodities 1 and 2 are complements in consumption, i.e., \(E_{q_{1}q_{2}}=E_{q_{2}q_{1}}<0\). However, a higher tax by one region still exerts an ambiguous impact on the other’s welfare.

Setting \(e_{u}\left( du/dt_{0}\right) =0\) and \(e_{u^{*}}^{*}\left( du^{*}/dt_{o}^{*}\right) =0\), in Eqs. (27) and (28), the Nash equilibrium origin-based consumption taxes are given as follows:

Consumption pollution without public pollution abatement: Destination-based consumption taxes

Totally differentiating Eq. (17), we obtain:

Totally differentiating Eqs. (20) and (17), after some algebra, yields:

An increase in the own destination-based consumption tax improves (worsens) Home’s welfare if it is lower (higher) than the household’s marginal willingness to pay for pollution abatement, e.g., \(\left( -e_{r}+t_{d}\right) <0(>0)\). A higher destination-based tax by Foreign improves Home’s welfare. Similar results are derived for changes in \(t_{d}\) and \(t_{d}^{*}\) on Foreign’s welfare.

Setting \(e_{u}\left( du/dt_{d}\right) =0\) and \(e_{u^{*}}^{*}\left( du^{*}/dt_{d}^{*}\right) =0\), in Eqs. (31) and (32), the Nash equilibrium destination-based consumption taxes are given as follows:

Using Eqs. (31), (32) and setting \(e_{u}\left( du/dt_{d}\right) +e_{u^{*}}^{*}\left( du^{*}/dt_{d}\right) =0\) and \(e_{u}\left( du/dt_{d}^{*}\right) +e_{u^{*}}^{*}\left( du^{*}/t_{d}^{*}\right) =0\) gives the cooperative destination-based consumption taxes:

Clearly, \(t_{d}^{C}>t_{d}^{N}\), \(t_{d}^{*C}>t_{d}^{*N}\).

Appendix 2

Interregional public consumption goods and the efficiency of Nash origin-based consumption taxes

Totally differentiating Eqs. (1) and (23), we obtain the effects of changes in \(t_{o}\) and \(t_{o}^{*}\) on G as follows:

Totally differentiating Eq. (24), changes in Home and Foreign’s welfare are given as:

Using Eq.(35) in Eq. (36), we obtain:

where \(e_{G}<0\) and \(e_{G}^{*}<0\), respectively, denote the marginal willingness to pay for the provision of the public consumption good in Home and Foreign. Contrary to \(e_{r}\) and \(e_{r^{*}}^{*}\) which are positive, \(e_{G}\) and \(e_{G}^{*}\) are negative. This is because, on the one hand, higher levels of r and \(r^{*}\) reduce welfare, thus requiring higher level of expenditure on private consumption goods to maintain a constant level of utility. On the other hand, higher levels of G increase welfare, thus requiring lower level of expenditure on private consumption goods to maintain a constant level of utility.

Interregional public consumption goods and the efficiency of Nash destination-based consumption taxes

Totally differentiating Eqs. (23) and (2), we obtain the effects of changes in \(t_{d}\) and \(t_{d}^{*}\) on aggregate G as follows:

Totally differentiating Eq. (24), changes in Home and Foreign’s welfare are given as:

Using Eq. (39) in Eq. (40), we obtain:

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Antoniou, F., Hatzipanayotou, P., Michael, M.S. et al. Tax competition in the presence of environmental spillovers. Int Tax Public Finance 29, 600–626 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-021-09680-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-021-09680-3