Abstract

The purpose of this study is three fold; first, it attempts to show to what extent Fielding’s writings unfold the basic characteristics of the eighteenth century lines of thinking, foremost of which is the importance of context for the determination of meaning. Second, it attempts to show Fielding’s philosophy of human nature which, according to him, is a mixture of man’s selfishness, greediness, honesty and charity, all of which are characteristics of the ‘characters’ nature. Third, the present study sheds some light on Fielding’s technique in writing. The importance of introducing ironic techniques is to stimulate the reader’s mental imagination to understand opposite meanings and in consequence adopt a proper evaluation of the character’s behaviour. Fielding discusses through irony some important concepts such as chastity, reason and gentility, yet no direct clue is given to the readers to give a precise interpretation about them. It is also through irony that the interpretation of these concepts are hindered by perplexing assumptions as connotations of meaning make it difficult for the readers to give any judgment or adopt any evaluation. The study shows that Fielding’s technique in ‘Tom Jones’ is incorporated within a third omniscience narrative, which gives the narrator the chance to preside over his creation and commenting on certain attitudes and actions. It concludes that the mark of shame bestowed by earlier critics on Fielding as intrusive narrator is eliminated on the grounds that his presence within the text is directed for teaching purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Applying linguistics to the study of literature has been evolving an increasing desire for investigation and evaluation. The study of literature implies the evaluation of style, and style itself works as an intermediary between language and literature. The present study is a stylistic analysis of language use and characterization in Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones from a socio-pragmatic perspective. It claims that a close—reading of the work based on a socio-pragmatic perspective can help illuminate intriguing aspects of Fielding’s novel and its relationship with its intellectual context; the role of contextualization in the creation of meaning; the idea that ideal character is of a mixed nature, and the use of satire and irony as main features of Fielding’s style, though which he attempts to capture the dual understanding of ‘charity’, chastity’, and ‘benevolence’. Some points have already been discussed by many critics such as the picaresque features in Fielding’s literary work and his narrative omniscient point of view, the God-like narrator and the role of the reader (see Alter, 1964; Apostoli, 2004; Ardila, 2010, 2015; Claude, 2007; Eisenberg, 2018; Jakubjakova, 2017; Mancing, 2015; Wicks, 2002; Birke, 2015; Iser, 1978; O’Halloran, 2007).

The purpose

The present study, first, attempts to show to what extent Fielding’s writings unfold the basic characteristics of the eighteenth-century lines of thinking, foremost of which is the importance of context for the determination of meaning. Fielding’s concern is mostly directed to the flexibility of language, to ways of making the mind more flexible and capable of drawing shades of meaning. Second, it attempts to show Fielding’s philosophy of human nature, which, according to him, is a mixture of man’s selfishness, greediness, honesty and charity, all of which are characteristics of the ‘characters’ nature. Fielding’s target is to expound that vice contradicts virtue and that there is no way for evil to prevail, thus it is the latter which ultimately triumphs over the former. In addition, the present study sheds some light on Fielding’s technique in writing. The importance of introducing ironic techniques is to stimulate the reader’s mental imagination to understand opposite meanings and in consequence adopt a proper evaluation of the character’s behaviour. Fielding discusses through irony some important concepts, namely, chastity, reason and gentility, yet no direct clue is given to the readers to give a precise interpretation about them. It is through irony that interpretations of these concepts are hindered by perplexing assumptions as connotations of meaning make it difficult for the readers to give any judgment or adopt any evaluation.

Organization of the study

The present study consists of six interrelated sections as follows: (1) Introduction/the purpose; (2) methodological background; (3) literature review, which covers four pertinent issues. Section “Discourse: Three approaches to discourse analysis” presents a review of the term ‘discourse’ and the three approaches in discourse analysis. Section “Language, linguistics, and literature” examines the relationship between language, linguistics and literature. Section “Stylistics and literary studies” examines the relationship between stylistics and literary studies, and section “Controversial views of Henry Fielding” deals with the controversial views of Henry Fielding. Section “Discussion” consists of four sub-sections. Section “Fielding’s narrative technique” deals with Fielding’s narrative technique’, section “Henry Fielding and the technique of irony in Tom Jones” deals with Fielding’s technique of irony in Tom Jones, section “Fielding’s characters in Tom Jones” deals with Fielding’s characters in Tom Jones, with special reference to the two concepts of ‘chastity’ and ‘charity’; section “A political reading of Tom Jones: Fielding as a political operative” presents a political reading of Tom Jones and Fielding as a political operative, which is mainly based on Hume (2010); section “Conclusion” presents the conclusions of the study and, section “Bibliography” presents the references of the study.

Methodological background

According to Mcintyre (2012, pp. 1–2), “it is a good idea to start [our analysis] with [our] initial thoughts and feelings about the text [we] are going to analyse. Then when we do the actual analysis, we can see if we were right or wrong in our initial interpretation. The linguistic structure of the text, sometimes, does not support our interpretation, in which case we may have to reconsider this in the light of our analysis. This is why stylistics is useful as a method of interpreting texts”. The stylistic analysis carried out in the present study is embedded within a framework of critical discourse analysis (CDA), as will be clarified later.

The present study uses the content analysis technique. Content analysis is a highly flexible research method that has been widely used. It is applied in qualitative, quantitative, and sometimes mixed modes of research frameworks and employs a wide range of analytical techniques. As a research methodology, it has its roots in the study of mass communication in the 1950s (Berelson, 1952; Busha and Harter, 1980; de Sola Pool, 1959; Krippendorff, 2004). Since then, researchers in many fields have used content analysis and, in the process, they have adapted content analysis to suit the unique needs of their research questions. They, also, have developed a cluster of techniques and approaches for analysing texts grouped under the broad term of textual analysis. As defined by Krippendorff (2004, p. 18), content analysis is a research technique for making replicable and valid differences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use. Such a definition emphasizes the fact that the notion of inference is especially important in content analysis.

The present study uses qualitative content analysis (QCA) as a research methodology. Qualitative content analysis is one of the several qualitative methods currently available for analysing data and interpreting its meaning (Scheier, 2012). As a research method, it represents a systematic and objective means of describing and quantifying phenomena (Downe-Wamboldt, 1992; Schreier, 2012). A prerequisite for successful content analysis is that data can be reduced to concepts that describe the research phenomenon (Cavanagh, 1997; Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Hsieh and Shannon, 2005) by creating categories, concepts, a model, conceptual system, or conceptual map (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). The research question specifies what to analyse and what to create ((Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Schreier, 2012). QCA is mainly inductive; that is, research questions guide data gathering and analysis. Its main objective, is ‘to capture the meanings, emphasis, and themes of messages and to understand the organization and process of how they are presented’. Relatedly, Krippendorff (2004, p. 00) refers to the objective of QCA as follows: ‘[to] search for multiple interpretations by considering diverse voices (readers), alternative perspectives (from different ideological positions, oppositional readings (critiques), or varied uses of the texts examined (by different groups).

The data used in content analysis studies must satisfy, at least, two conditions; first, the data must provide useful evidence for testing hypotheses or answering research questions; and, second, the data communicate or provide a message from a sender to a receiver. Both conditions are quite satisfied in the data of the present study; namely, Fielding’s work, Tom Jones. Moreover, in QCA studies, including the present study, the data are subject to purposive sampling to allow for identifying complete, accurate answers to research questions. It is, also, important to emphasize the point that selection of the data has been a continuous process. Analysing the data is integrated into coding much more in qualitative content analysis than in quantitative content analysis. The emphasis is always on answering the research questions.

The most widely used criteria for evaluating qualitative content analysis are those developed by Lincoln and Guba (1985). They used the term trustworthiness. The aim of trustworthiness in a qualitative inquiry is to support the argument that the inquiry’s findings are ‘worth paying attention to’ (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). This is especially important when using inductive content analysis as categories are created from the raw data without a theory-based categorization matrix. Several other trustworthiness evaluation criteria have been proposed for qualitative studies (Emden et al., 2001; Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Neuendorf, 2002; Polit and Beck, 2012; Schreier, 2012). However, a common feature of these criteria is that they aspire to support the trustworthiness by reporting the process of content analysis accurately. Lincoln and Guba (1985) have proposed four alternatives for assessing the trustworthiness of qualitative research, that is, credibility, dependability, conformability, and transferability.

Literature review

Discourse: Three approaches to discourse analysis

Defining ‘Discourse’

‘Discourse’, used as a mass noun, means roughly the same as ‘language use’ or ‘language-in-use’. As a count noun (a discourse), it means a relatively discrete subset of a whole language, used for specific social or institutional purposes. More specifically, ‘discourse’ as a mass noun and its strict linguistic sense, refers to connected speech or writing occurring at suprasentential levels. As Van Dijk (1985) points out, our modern linguistic conception of discourse (as language use) owes much to the ancient distinction between grammar and rhetoric. Grammarians explored the possibilities a language can offer a ‘calculus’ for representing the world, and were concerned with correctness of usage. By contrast, rhetoricians focused upon practical uses of speech and writing as means of social and political persuasion. In this regard, Georgakopoulou and Goutsos (1999) point out “despite the centuries-old tradition of the mother discipline of rhetoric, three decades ago there were only two isolated attempts to study language beyond the sentence with specifically linguistic methods; namely Harris (1952) and Mitchell (1957).

The approaches to discourse analysis

There are three main approaches to discourse and its analysis in contemporary scholarship: (1) the formal linguistic approach (discourse as text); (2) the empirical sociological approach (discourse as conversation) and (3) the critical approach (discourse as power/knowledge). It should be borne in mind, however, that each approach is, in itself, a multi-disciplinary; each has its own controversies, and contradictions. However, each is sufficiently different from the others.

The Text-Linguistic Perspective is often referred to as the ‘formal approach’ to discourse. It tends, largely, to construe discourse as text. It is the most direct descendant of Harris (1952) and Mitchell (1957). Like Harris, it continues to have faith in formal linguistic methods of analysis. Like Mitchell, it moves linguistics, as a different discipline, as mainly been in the direction of social functions and naturally occurring samples. A more recent heir to the formalist approach has been ‘Text Linguistics’ (TL). The term was pioneered by Van Dijk (1972) and later developed by De Beaugrande (1980, 1984) though Van Dijk has, to some extent, recast TL as discourse analysis.

As previously mentioned, the ongoing use of texts in their communicative environment; that is, in their contexts, has been referred to as ‘discourse’. ‘Discourse’ and ‘text’ have been used in the literature in a variety of ways. In some cases, the two terms have been treated as synonyms, while in others the distinction between discourse and text has been taken to apply to units of spoken versus written communication. Consequently, discourse analysis is, in some accounts, regarded as concerned with spoken texts (primarily conversation). Text linguistics, as a different discipline, has mainly been associated with written texts. According to Georgakopoulou and Goutsos (1999, p. 3) the two terms do not refer to different domains (speech and writing) but reflect a difference in focus. In this regard, Slembrouk (2003, p. 1) points out that “Discourse analysis does not presuppose a bias towards the study of either spoken or written language. In fact, the monolithic character of the categories of speech and writing is increasingly being challenged”. Discourse, then, is the umbrella term for either spoken or written communication beyond the sentence. Text is the basic means of this communication, be it spoken or written, a monologue or an interaction. Discourse is, thus, a more embracing term that calls attention to the situated uses of text: it comprises both text and context. However, text is not just a product of discourse, as customarily assumed (Brown and Yule, 1983), that is, the actual (written or spoken) record of the language produced in an interaction. Text is the means of discourse, without which discourse would not be a linguistic activity (see El-dali, 2011, 2012, 2019a, 2019b; Boisvert and Thiede, 2020; Hart, 2020).

The empirical approach consists of sociological forms of analysis which have taken ‘discourse’ to mean human conversation. Its object has been not merely the formal description of conversational ‘texts’, but also the common sense knowledge at the basis of conversational rules and procedures. The most fruitful work to date has been accomplished in the area of conversation analysis (CA). The major strength of conversation analysis lies in the idea that an important area of interactional meaning is revealed in the sequence. Its most powerful idea is that human interactants continually display to each other, in the course of interaction, their own understanding of what they are doing. This, among other things, creates room for a much more dynamic, interactional view on speech acts.

In Fairclough’s words, (1992, p. 7) the critical approach “is not a branch of language study, but an orientation towards language … with implications for various branches. It highlights how language conventions and practices are invested with power relations and ideological processes which people are often unaware of”. To that end, this approach investigates language behavior in everyday situations of immediate and actual social relevance: discourse in education, media and other institutions. It does not view context variables to be correlated to an autonomous system of language; rather, language and the social are seen as connected to each other through a dialectical relationship. Texts are deconstructed and their underlying meanings made explicit; the object of investigation is discursive strategies which legitimize or ‘naturalize’ social processes (Orpin, 2005; K. O’Halloran, 2007; Campbell and Roberts, 2007). Van Dijk (2006, 2008a, 2008b) argues that it is not the social situation itself that influences the structure of text and talk, but rather the definition of the relevant properties of the communicative situation by the discourse participants. Van Dijk (2008a, p. ix) argues that “the new theoretical notion developed to account for these subjective mental constructs is that of context models, which play a crucial role in interaction and in the production and comprehension of discourse. They dynamically control how language use and discourse are adapted to their situational environment, and hence define under what conditions they are appropriate”. According to Van Dijk, context models are the missing link between discourse, communicative situations and society, and hence are also part of the foundations of pragmatics. As Van Dijk (2008a, p. vii) points out “in most of the disciplines of the humanities and social sciences there is growing but as yet unfocused interest in the study of context”.

In conclusion, “while it is correct to say that discourse analysis is a subfield of linguistics, it is also appropriate to say that discourse analysis goes beyond linguistics as it has been understood in the past … discourse analysts research various aspects of language not as an end in itself, but as a means to explore ways in which language forms are shaped by and shape the contexts of their use.” At the same time, discourse analysis is a cross-discipline and, as such, finds itself in interaction with approaches from a wide range of other disciplines. Discourse analysis is, thus, an interdisciplinary study of discourse within linguistics: “Discourse analysis is a hybrid field of enquiry. Its ‘lender disciplines’ are to be found within various corners of the human and social sciences, with complex historical affiliations and a lot of cross-fertilization taking place” (Slembrouk, 2003, p. 1). It must be emphasized, however, that a single, integrated and monolithic approach is actually less satisfactory than a piecemeal and multi-theoretical approach.

Language, linguistics, and literature

Language is one of the most important aspects of communication. Nowadays, we can find almost everybody around us using a particular language to communicate. Language is a wonder as it helps to spread our ideas, thoughts and let others know about our mood through time, space and culture. In addition, if one were to take an informal survey among non-linguists regarding the primary function of human language, the overwhelmingly most common answer would be, “language is used for communication”. As Van Valin (2001, p. 319) maintains, “this is the common sense view of what language is for”. However, some of the most prominent linguists in the field reject this view, and many others hold that the fact that language may be used for communication is largely, if not completely, irrelevant to its study and analysis (See Evans, 2018: Simpson et al., 2018; Mooney et al., 2011). In other words, the majority of professional linguists used to adopt a view of language which is at odds with the view held by non-linguists. The phenomenon of communication has often been thought of as peripheral in linguistic research. This view is a result of the strong hold the abstract objectivist language conception has had on modern linguistic thought. Communication has been reduced to a subordinate place amongst the possible functions of language. This low status attributed to communication is challenged by different pragmatic approaches to language. On the other hand, the content and use of the term ‘communication’ is even by humanistic standards extremely ambiguous, and it has, therefore, often been difficult to use in practical, empirical work.

The primary concern of linguists such as Franz Boas and Ferdinand de Saussure at the start of the 20th century was to lay out the foundations for linguistic science and to define explicitly the object to be investigated in linguistic inquiry. Carston (1988, p. 206) points out that “before Chomsky, linguistics tended to be a taxonomic enterprise, involving collecting a body of data (utterances) from the external world and classifying it without reference to its source, the human mind.” Chomsky (1965) proposed a distinction analogous but not identical to Saussure’s and Bloomfield’s, namely competence vs. performance. In his distinction, Chomsky sees that the proper domain of linguistic inquiry is competence only. In the Chomskyan linguistic tradition, well-formedness plays the role of the decision-maker in questions of linguistic ‘belonging’. That is, a language consists of a set of well-formed sentences: it is these that ‘belong’ in the language, no others do. This is the definition that has been the bulwark of the Chomskyan system since the late 1950s.

Linguistic studies which depend upon elicitations from only one or a few informants are now recognized as leaving unanswered many significant questions about the relation between language and the social context in which it is always embedded. Language is no longer viewed “as a closed system, but as one which is in perpetual flux” (Johnson, 2002, p. 16). Moreover, the extraordinary growth of sociolinguistics in the last decade or so has shown convincingly that language is closely linked to its context and that isolating it artificially for study ignores its complex and intricate relation to society.

The idea of extending linguistic analysis to include communicative functions was, first, proposed by Czech linguists. As Van Valin (2001, p. 328) points out, “all contemporary functional approaches trace their roots back to the work of the Czech linguist Mathesius. By the end of the 1970s, a number of functional approaches were emerging in both U.S. and Western Europe. Some of the most important and coherent attempts of communication-relevant approaches to language are (1) Soviet Semiotic Dialogism; (2) The Prague School, and (3) Functionalism (see McHoul, 1994). More specifically, Halliday attempted to explain the structure of language as a consequence of social dialogue. According to Halliday (1978, p. 2), language does not consist of sentences; it consists of interactional discourse. People exchange meanings in socially and culturally defined situations. When they speak to each other, they exchange meanings, which reflect their feelings, attitudes, expectations and judgments. In this regard, Bates (1987) noted that functionalism is like ‘Protestantism’, a group of warring sects, which agree only on the rejection of the authority of the Pope. All functionalists agree that language is a system of forms for conveying meaning in communication and, therefore, in order to understand it, it is necessary to investigate the interaction of structure, meaning and communication. As Van Valin (2001) points out, functionalists normally focus on linguistic functions from either of two perspectives; the first is referred to as the ‘pragmatics’ perspective, and the second as the ‘discourse’ perspective. The first concentrates on the appropriate use of different speech acts. The second perspective is concerned with the construction of discourse and how grammatical and other devices are employed to serve this end.

Employing the linguistic rules on artistic works results in what is known as stylistics. It has to do with the different uses of words, expressions, sentence-structures and speech sounds in a given text. Stylistics is a branch of linguistics, while the latter investigates no units larger than a sentence, the former examines bigger units of linguistic formation. Such bigger units of linguistic formation, constitute the context of a work, known as the style of an author. The way of writing of an author is also called register. Chapman (1973, p. 11) states that the distinctive usages of languages are known as styles; and that the “Linguistic study of different styles is called stylistics”. Stylistic analysis of a given text which functions through linguistics, primarily aims at the analysis of discourse in such text. Short (1986, p. 158) states that the stylistic analysis has to do with criticism, through which evaluation, interpretation, and textual description of a literary work are identified. The realtion of linguistics to literary criticism is what Chomsky (1968, p. 81) has called, “The close relation between innate properties of the mind and features of linguistic structure”.

The importance of conducting a study of literary language by means of linguistics, has taken the form of ‘Discourse Analysis’. However, the application of linguistic characteristics to literary texts, has proved that literature has linguistic form and that some sort of harmony exists between linguistics and literature. Stylistics which is a branch of linguistics, investigates the relationship between style and literary function or the application of linguistic characteristics to literary language. Richards (1985) states that stylistics is associated with the study of style, based on the situation in which the writer, speaker or addressor intends to create on the reader, hearer or addressee. Although stylistics sometimes contemplates spoken language, it mainly refers to the study of written language. The different uses of words, expressions, sentence-structures and speech sounds are incorporated with the stylistic characteristics of a given text. Carter (1986, p. 19) says that there are two branches of stylistics, namely linguistic stylistics and literary stylistics. The former kind studies ways of anlysing samples of style and language, especially the non-liteary language. The latter kind of stylistics, namely, literary stylistics, studies methods of conceiving, interpretating and estimating the literary works, by virtue of criticism. It also studies ways of analysing literary discourse, especially as regards the narrative techniques. Leech (1981, p. 11) states that stylistics, “is simply defined as the linguistic study of style … (and) simply (is) an exercise in describing what use is made of language”. In the meantime Leech tries to explain the aim of literary stylistics, indicating that its target is to expound the relationship between language and the artistic function.

The function of stylistics is to expound interpretations already existing within the context of a comprehensive unit of linguistic performance. Short (1986) attempts to enumerate levels of interpretation within a literary discourse. “Copiousness”, for instance examines sentences in case that “they are long and have lots of clauses within them”. “Simplicity” examines the style, if it is simple or not. Simple style shows that an author does not attempt to puzzle the reader by complex formations. “Sequencing” among the levels of interpretations reflects the order in which the events of a discourse has taken place, the order in which the thoughts of a character in a literary work have occurred and the order in which the addressor or the writer depicts the information to his addressees or readers.

Style indicates the route in which language operates in a given context. Style is a term used to show the function of language in spoken and written discourse as well as in literary and non-literary fields. The word in its wide sense, covers also the way of writing of any author; and it is an instrument by virtue of which, a linguist could examine the choices worked out by an author in a particular context. Style also identifies the method of using language either during a certain era or by a certain school of writing. In this connection Leech (1981) states that style is “the linguistic characteristic of a particular text”. He adds that style is “a property of all texts”. Fowler (1971) states that style is examined on two levels; the first is the level of context which includes all utterances within a text and utterances in their term are formed through a successinve sequence of sentences. Brown (1983) differentiates between sentences and utterances, stating that the features of spoken language are considered the features of utterances and that the characteristics of written language belong to sentences. However, the features of utterances are the output of ordinary language beahviour. The second level of style is examined within the framework of the form including ways of organisation within a text. Style includes two models. Lang (1983) says that the first model of style is associated with the noun, dealing with the stylistic practice, only to attach to an object the names of genres, figures of speech or periods of time. The second model of style is that which has a nominative function dealing with categories of style, including life styles, styles in dress or artistic style. Chapman (1973, p. 6) quotes Quiller Couch’s remark on style saying that, “Style in writing is much the same as food manners in other human intercourse”.

The modern work in linguistic stylistics have divided style into various types. Freeman (1970) says that there are three types of style; style deviating from a specified course; style as divergence of textual pattern and style utilizing grammar potentials. The former kind of style is that which suggests that an author’s method of writing could differ in certain ways in various fields of utilization. The second kind of style is associated with examination of the coherence elements within a text. Cohesion for instance examines the use of determiners, pronouns, demonstratives, and adverbs as being hinted before. Lack of cohesion affects the literary prose. The last kind of style accounts for a kind of grammar that foretells the language used in a text. In this connection, language is to be judged on two levels of representaiton, the deep and surface syntactic structures. Semantic interpretation proceeds from deep structure and phonetic interpretation proceeds from deep structure and phonetic interpretation stems from surface structure. The two levels are related by a set of transformations and the use of particular sets of transformations shape the syntactic style of an author. Any kind of style to be undertaken by an author is to be called “register”. Using a particular kind of style such as the religious style or the legal style, probably means that an author is adopting a ‘register’. Fowler (1971) quotes Leech attempting to identify register saying “(it distinguishes) for example, sopken language from written language, the language of respect from the language of condescension, the language of advertising from the language of science”. Register is a speech variety used by a particular group of people usually sharing the same occupation. Richards (1985) says that register is, “a particular style … referred to as a stylistic variety”.

Chapman (1973) states that it is highly important that a writer chooses registers aligning the situations they depict. Combining a number of registers together without idnetifying the speakers and the shifting of utterances are subjects worthy of study through stylistics. According to Leech (1981) style in discourse is divide dinto three categories of language use, namely, domain, mode and tenor. Domain is the scale of register. The professional jargon in a certain variety of language is the typical feature of domain. The language of science differes from that of engineering. Thus domain seems to deal with the activity of language within a specific context. The distinction between speech and writing is oncorportated within the category of mode. The relaitonship between the speaker and the addressee(s) is the focal point in the category of tenor. Their relationship whether official and distant, or unofficial and close determines the way of use, either formal and complex or informal and simple; polite showing indirect request or familiar showing direct imperative, impersonal done in the passive form of personal done in the active form. However, the category of tenor in the literary works has to do with the point of view operational in such activities. As long as such viewpoint is to be communicated through language, then the medium of language has to be also investigated (see Peck, 2011; Hardavella et al., 2017; Fong Ha et al., 2010).

Stylistics and literary studies

Referring to the title of her article ‘Fielding’s Style’, Campbell (2005, p. 407) made the following remark: “The topic announced by this essay’s title is seemingly old-fashioned—perhaps some would even say, reactionary. The word “style” invokes questions of aesthetic appreciation that several decades of contextualizing criticism in the 1970s, and 1990s moved far from the center of literary study; to attempt to describe an individual author’s style might seem to bespeak an antiquated belief in some ineffable quality adhering in that author, independent of his historical period or circumstances and of the import of his work”. In what follows, I will show how important it is to link linguistics to literature and to what extent stylistics is valuable. As Levine (1996) points out “[W]e have to understand that if there is no literature, there is no profession [of literary studies]”. Less strictly pragmatically, he added his spare attestation of faith that literary study consists of “reading the sorts of texts that test most fully the possibilities of language and meaning, and using skills developed to engage those texts successfully. In this regards, McIntyle (2012, p. 1) points out that since the emergence in the 1960s of English Language as a university subject in its own right, the relationship between the study of literature and the study of language has often been one of bitter rivalry. Literary critics have railed against the ‘cold’, ‘scientific’ approach used by scholars of language in their analyses of literary texts, whilst linguists have accused their literary colleagues of being too vague and subjective in the analyses they produced. Nowhere is this disagreement more clearly seen than in the clash between Bateson and Fowleer (see Fowler, 1971), which had the unfortunate effect of dragging the debate down to the level of personal insult. Fowler’s famous question to Bateson asking him whether he would allow his sister to marry a linguist represents, perhaps, the nadir of this particular argument. The relationship between literature and language, then, has, for the most part, been an unhappy one, and this is unfortunate since undoubtedly scholars in both disciplines have much to learn from one another. It is possible to bridge the divide between language and literature by using the anlytical techniques available within the sub-discipline of language study known as stylistics. Taking a linguistic approach to the analysis of a literary text does not have to mean disregarding interpretation. Stylistic analysis can often illuminate just why a particular literary text is regarded so highly. Stylistics acknowledges the skills of the writer by assuming that every decision made in the production of a text is deliberate, despite whether these decisions were made consciouly or unconsciously. Consequently, stylistics aims to explain the link between linguistic form and literary effect, and to account for what it is that we are responding to when we praise the quality of a particular piece of writing.

A further aspect of textual analysis with which some stylisticians concern themselves and about which others have reservations, is the study of the extent to which interpretation is influenced by tensions between the text and its reception in the wider context of social relations and socio-political structures. In some contexs stylistic analysis has become embedded within a framework of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). In this way, explorations of ideology and social power feature as part of a stylistic analysis with attention paid both to the formal features of the text and to its reception within a reading community. This development has been the subject of some controversy, not least because all texts chosen for analysis may generate ideological considerations and interpretations according to the disposition of the individual analyst. Nevertheless, despite such criticisms, CDA has been the first attempt so far to formalise a methodology that seeks to articulate the relationship between a text and the context in which it is produced, received and interpreted, thus moving beyond a concern with wholly text immanent interpretation and considering wider social and cultural issues. Thus, what has emerged in both theory and classroom practice is the view that, although there are not an infinite number of possible interpretations and although it would be wrong to suggest that anything goes, there is no single ‘correct’ way of analysing and interpreting the text. In this sense, the appropriate method is very much a hands-on approach taking each text on its own merits, using what the reader knows, what the reader is aiming for in his or her learning context, and employing all of the available tools, both in terms of language knowledge and methodological approaches. It is a process-based methodology which encourages learners to be active participants in and explorers of linguistic and cultural processes both with an awareness of and an interest in the process itself, including the development of a metalanguage for articulating responses to it.

On the other hand, the last twenty years have seen significant advances in linguistics, education and literary and cultural theory, a development that has provided a strong basis for exploring texts using a diverse range of methodologies (see Hall, 2005 for a comprehensive survey). Literary theory has embraced many topics, including the nature of an author’s intentions, the character and measurement of the responses of a reader and the specific textuality of a literary text. In particular, there has also been a continuing theorisation of the selection of literary texts for study, which has had considerable resonance for the teaching of literature and for its interfaces with the language classroom. On the one hand, there is a view, widespread still internationally, that the study of literarure is the study of a select number of great writers judged according to the enduringly serious nature of their examination of the human condition. On the other hand, there is the view that the notion of literature is relative and that ascriptions of value to texts are a transient process dependent on the given values of a given time. How tastes change and evaluations shift as part of a process of canon formation are therefore inextricably bound up with definitions of what literature is and what it is for. ln this respect, deftnitions of literature, and of literacy language are either ontological establishing an essential, timeless property of what literature or literary language is - or functional - establishing the specific and variable circumstances within which texts are designated as literary, and the ends to which these texts are and can be used. Recent work on creativity and language play has reinforced this awareness of both continuities and discontinuities in degrees of literariness across discourse types (Cook, 1994, 2000; Pope, 2005). One outcome has been the introduction into language curricula, for both first and for second or foreign language learners, of a much greater variety of texts and text-types so that literary texts are studied alongside advertisements, newspaper reports, magazines, popular song lyrics, blogs, internet discourse and the many multi-modal texts to which we have become accustomed (see Carter, 2010).

In the early part of the twentieth century, learning a foreign language meant a close study of the canonical literature in that language. In the period from the 1940s to the 1960s literature was seen as extraneous to everyday communicative needs and as something of an elitist pursuit. However, in the 1970 and 1980s the growth of communicative language teaching methods led to a reconsideration of the place of literature in the language classroom with recognition of the primary authenticity of literary texts and of the fact that more imaginative and representational uses of language could be embedded alongside more referentially utilitarian output. This movement has been called the ‘proficiency movement’ which saw in literature ’an opportunity to develop vocabulary acquisition, the development of reading strategies, and the training of ctitical thinking, that is reasoning skills’. They point out how awareness dawned that literature, since it had cominuittes with other discourses, could be addressed by the same pedagogic procedures as those adopted for the treatment of all texts to develop relevant skills sets, especially reading skills, leading in particular to explorations of what it might mean to read a text closely (see Alderson, 2000).

Controversial views of Henry Fielding

In his survey of Henry Fielding, Hume (2010) attempted to remind readers of two major issues: (1) just how wildly views of Fielding have varied, early and late; and (2) how radically the dominanat late twentieith-centrury reading contradicts eighteenth-century assessments of Fielding and his work. Henry Fielding, according to Hume, proved exceptioally controversial and his reputation has variously soared and crashed in the course of three centuries. Fielding’s reputation suffered from two factors. The first is that he wrote about low subjects. He did not always preserve the dignity of the clergy; his work features bastards and fornicators; the world of crime and squalor depicted even in the relatively exemplary Amelia bothered many of his genteel readers. For his time, he was much more radical writer than most readers now realize. The second factor that guaranteed the blackening of Fielding’s reputation was the history of his changing political allegiances and his scandalous personal life. His appointment as justice of the peace for Westminister in October 1748 and his becoming magistrate for Middlesex County provoked ridicule and hostile outcry.

Fielding’s disorderly personal life put ammunition into the hands of his litrary enemies, who seized on the lowness of his fictional subjects with spiteful glee. The picture one gets from public and private commentary during Fielding’s lifetime is of a hard-living man of violent passions (positive and negative) who could not manage money competently and could or would not accommodate himself to the codes and pretenses of an urbane upper class to which he did not really belong. Fielding’s reputation, as Rawson (1959) observes “always suffered from that eighteenth-century cult of ‘sensibility’ which professed itself too refined for scenes of coarse or low life, and too tender-hearted for satire”. Fielding was not without some defenders. Harold Child points out that “Fielding established the form of the novel in England”; that Tom Jones (1749) entitles him to be called “the father of the English novel”; and that he “had fixed the form of a new branch of literature”.

Early nineteenth-century writers are less fixated on the writer’s life. During the twentieth-century, critical evaluation of his writing underwent a drastic change. For fully two hundred years, Fielding was usually seen as “the great structuralist and technician” and contrasted with Richardson—“the great moralist”. Fielding was sometimes condemned for being crude and immoral, sometimes praised for realism, and sometomes just enjoyed as a creator of jolly English romps. His literary morals were sometimed defended, but hardly anyone saw him as a writer whose cenrtral concern was moral instruction. The radical reorientation that occurred in the ways Fielding was read and understood is now largely associated with Battestin’s The Moral Basis of Fielding’s Art (1959). For a majority of the critics of the last half century, moral sermonizing is what has been taken as “most characteristic” of Fielding. In addition, Hume (2010, p. 258) argues that Fielding’s writing has three major characteristics. The first is that Fielding is experimental; in the sense that he is not trying to associate himself closely with predecessors and traditions. Fielding’s debts to earlier writers are unusually minimal, and he does not stick to one or two models in drama or fiction. He innovates, experiments, and takes chances. A second major feature of Fielding’s writing is that it is circumstantial. Fielding deals with and reacts to the events, issues, politics, quarrels, social problems, and stresses of his place and time, and he does so as a hackney writer out to make a quid. He does not imagine alternative worlds, idealized worlds, or past worlds. He is an engaged observer, a participant, a partisan. He is an opportunist who will keep silent or change sides; he puts the advantage of occasion above abstract principle, moralist through he is. Fielding deals—sometimes humorously, sometimes not—with a grubby milieu of crime, deceit, and lust. What many of his contemporaries condemned as “low” we should regard as “realistic”, at least in the terms of literature as it was written in Fielding’s time.

A third characteristic of Fielding’s writing is its didacticism:

I say this with some hesitation, because didacticism is not a positive quality for most present-day readers, academic or otherwise, who regard it as boring, irritating, and preachy (Hume, 2010, p. 259).

Today Fielding is universally acknowledged as a mjor figure in the development of the novel, although there is still niggling about whether he or Richardson is the “father” of the British novel.

Discussion

Fielding’s narrative technique

Choosing a narrative point of view is perhaps the most important and most difficult decision a writer of a story can make. Point of view, like plot, character, setting, and language is a creative decision; however, it is also very much a technical decision. Someone has to tell the story. That someone is called the narrator. The question is who will that narrator be and what does that narrator know. Abrams (1981, p. 142) identifies the point of view, saying that it “Signifies the way a story gets told, the mode or perspective established by an author by means of which the reader is presented with the characters, actions, setting and events which constitute the narrative in a work of fiction”.

The point of view in a literary composition represents the aspect from which the story telling and seeing is calibrated. It does not only represent the dimension from which the author projects his scene but also sets out the aspect from which the reader is to view it. Point of view is the perspective from which a story is narrated. Every story has a perspective, though there can be more than one type of point of view in a work of literature. The choice of the point of view from which to narrate a story greatly affects both the reader’s experience of the story and the type of information the author is able to impart. First person creates a greater intimacy between the reader and the story, while third person allows the author to add much more complexity to the plot and development of different characters that one character wouldn’t be able to perceive on his or her own. The point of view in an artistic work represents the significance of its overall form. Tackling the significance of the point of view, Allot (1959, p. 181) indicates that the most complicated matter in the craft of fiction is “… to be governed by the question of the point of view—the question of the relation in which the narrator stands to the story”. Point of view is very closely linked with the concept of a narrator. Point-of-view impacts how close the reader feels to what’s happening in the story. The narrator acts, as a proxy for the reader and how close the narrator is to the story is how close the reader will be to the story (see Peck, 2011; Hardvell et al., 2017).

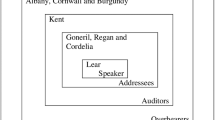

The narrators of Fielding’s Tom Jones focus on the omniscient point of view in which the third-person narrative is outside the story referring to characters either by their name or by the pronouns, “he, she and they”. An omniscient narrator is more able to present a complete and unbiased story. We can learn not only what a character does, but also what other characters do when the main character is not present. Abrams (1981, p. 143) sees that the narrator of the omniscient point of view “knows everything that needs to be known about the agents and events; that he is free to move as he will in time and place, and to shift from character to character, reporting …what he chooses of the speech and actions; and also that he has privileged access to a character’s thoughts and feelings and motives, as well as to his overt speech and actions”. The narrator begins Joseph Andrews: “Mr. Joseph Andrews, the hero of our ensuing history, was esteemed to be the only son of Gaffer and Gammer Andrews … whose virtue is at present so famous” (Book 1, Ch. 2, p. 41). It is also the way that the narrator of Tom Jones starts “In that part of the Western division of this kingdom which is commonly called Somerset-Shire, there lately lived, and perhaps still lives a gentleman, whose name was Allworthy …” (Book 1, Ch. 2, p. 53).

The narrator tends to put the overall work into a wellbeing form; he plays the God-like role and the ruler who presides over his fictitious or real formation. The narrator spells out the function he undertakes “The writer may be celled in aid to spread their history farther, and to present the amiable pictures to those who have not the happiness of knowing the originals; and so by communicating such valuable patterns to the world, he may perhaps do a more extensive service to mankind …” (Book 1, Ch. 1, p. 39). The writer in this respect seems to have almost cognizance of the historical aspects and thus he presents just those patterns which are of vital importance to the service of mankind. Allot (1959, p. 188) states that the eighteenth century writers among them Fielding, attempt to adopt the first person narrative view-point within the context of an exterior third person narrative. This is of course, clearly hinted in the digressive tales of the two books which are merely old methods of narration.

Throughout The History of Tom Jones, A Foundling (1749) Henry Fielding makes his presence felt. He lectures, teases and cajoles the reader, ponders the difficulties of his task, and draws attention to his deft arrangement of material. In short, he never lets us forget that he is telling a story, and that we are reading a book. One of the most prominent features of Fielding’s intrusive narration is his frequent direct address to an imagined reader. The characteristic Fielding most frequently attributes to his reader is sagacity. Early in the novel, for example, after comparing Mrs. Wilkins—Squire Allworthy’s formidable housekeeper—to a bird of prey, he breaks off:

The sagacious Reader will not, from this Simile, imagine these poor people had any Apprehension of the Design with which Mrs. Wilkins was now comong towards them; but as the great beauty of the Simile may possibly sleep these hundred years, till some future commentator shall take this Work in hand, I think proper to lend the reader a little Assistance in the Place.

Fielding constantly makes reference to the reader’s sagacity, or speculates as to how his ‘Sagacious Reader’ might interpret a particular scene. In all, he uses the word sagacious and its cognates (‘sagacity’, ‘sagaciousness’, etc.) 41 time when speaking in his own person. It is never used by any other character. Fielding narrative style was much imitated in the decade following the publication of Tom Jones. Early in the novel, having introduced us to the principla characters, Fielding announces that he wil pass over a space of around twelve years in silence (since the incidents which took place in this period are not immediately relevant to his narrative), and in doing so reflects on the nature of his relationship with the reader:

We give him all such Seasons an Opportunity of employing that wonderful sagacity, of which he is Master, by filling up these vacant Spaces of Time with his own Conjectures; for which Purpose, we have taken care to qualify him in the preceding Pages (T.J. III.i, p. 116).

From the very beginning of the book, the reader is acquainted with the fact that the story will be formed in proportion to the self-conscious caprice of an individual, pertaining to the outward existence of the world of the book. The work is categorized as an art as much as a reflection of life. The book begins with the introduction of the author as regards the narrative role. The course of events is worked out by a skilful artist and the progress of the novel’s picaresque episodes are not known in advance. Fielding’s technique in his novels is dissimilar to that adopted in Richardson’s novels, mostly undermines the existence of genuine suspense, “what will happen next?” Although heroic persons and sublime thoughts are major components of characters and sentiments in the epic genre, they are undermined in Tom Jones. As for the epic diction, it is highly used in burlesque form. Fielding’s marked imitation of the epic action is the mock heroic battles with obvious realism and with the life of the time. A distinction has been drawn between burlesque and comedy, while the former makes a subject appears ridiculous by treating it in an incongruous style as by presenting a lofty subject with vulgarity, the latter makes a subject appear humorous in its treatment of theme and character. Incongruity and absurdity are the sources from which we derive our delight at burlesque. They are also the essence of our delight at affectation, being the representation of the ridiculous. On attempting a distinction between burlesque, or its synonym ridicule, and comedy, Fielding is rectifying what has been said by Locke about the ‘abuse of words’, which is manifested in a gap between word and things (see Simpson et al., 2018; Mooney et al., 2011; Hammudin, 2012): “An author ought to consider himself, not as a gentleman who gives a private or eleemosynary treat, but rather as one who keeps a public ordinary, at which all persons are welcome for their money” (Fielding’s Tom Jones, Bk 1, Ch. 1, p. 51). Meeting the narrator early in the book before the hero, is significant; since the narrator is neither objective nor omniscient, but rather a deliberate awareness whose relationship with the reader influences his interpretation and judgment of what is going on.

James (1968, pp. 13–14) has felt sorry that Tom, the hero, has fallen a prey to clouds of mind, perplexity and confusion, although a hero in his own eyes ought not to be in such a situation. He suggests that the author of Tom Jones: “handsomely possessed of a mind, has such an amplitude of reflexion for him and round him that we see him through the mellow air of Fielding’s fine old moralism, fine old humour and fine old style, which somehow really enlarge, make everyone and everything important”. Werner (1973, p. 71) points out that Fielding’s narrative technique is indeed complex. Miller indicates that his rhetoric is carefully calculated to achieve specific ends. All these are indicators that Fielding, unlike Richardson, does not explore the depths of human nature but registers the external surface of the human behaviour (Miller, 1981, p. 209). Fielding’s most successful works stand closely with Swift rather than Richardson. Fielding resembles swift as both stress the importance of the uses of language. Accordingly, the narrative consciousness becomes important; it does not only project awareness but also affects the response of the reader and his reappraisal of the presented material.

Henry Fielding and the technique of irony in Tom Jones

Hume (2010, p. 285) points out that our concept of early eighteenth-century satire is heavily colored by the array of books and articles published in the third quarter of the twentieth century by such eminent scholars as Maynard Mack, Ian Jack, Robert C. Elliott, Alvin Kernan, and Paulson. Their notions came largely from Pope and Swift, for whom attack was the basic motivation of satire. This is rarely true for Fielding, for whom instruciton is much more central.

Arriving at the truth is a focal point on the level of the plot of Tom Jones. The story begins with an esoteric and obscure birth and ends with the unraveling of this mystery. When the truth is revealed the book has given a line of unity. The theme of the novel is marked by ways of unfolding truth and divulging deceit. Irony which is used throughout the book enhances this theme, since it is built on double meaning, and on this account one attempts to seek the truth, which, lies behind the false appearance. Hatfield claims that Fielding: “Takes a word which, by virtue of the abusage of ‘custom’ has already a kind of built-in ironic potential, and playing this ironigenic corrupt sense against the ‘proper and original’ meaning of the word that is developed in the definition of action, seeks to restore the word to its rightful dignity of meaning” (Hatfield, 1968, pp. 191–192). Irony relies on double connotations of meaning that, are to be supplied by the narrator, but this does not suggest that it is based on custom. A further point, Fielding does not intend by writing a novel to restore a word to its rightful dignity of meaning, unless it is meant by Hatfield that he attempts to eliminate any corrupt use of a word. Hutchens (1965, p. 111) proposes that irony is produced by a gap between the accepted meaning of a word and its meaning in the context it occurs. However, Hutchens seems to be like Levine, as both consider irony not only a means through which, the nature of the characters is exposed but also it serves as a means of establishing truth. Hutchens states that: “The … techniques, of connotative irony … by suggesting what is not true or good or appropriate, throw into sharp relief what is" (Hutchens, 1965, p. 146).

Irony as one of the distinguished devices exploited in Tom Jones, mainly unravels connotations of meanings and the nature of the characters. Irony in the limited sense of the word is relevant to the use of words for conveying the opposite of their literal meaning; or it might be identified as an expression or utterance marked by a deliberate contrast between apparent and intended meaning. The aim behind these contrasts of meaning is to initiate humours or rhetorical effects. It might be notable as well that incongruity arises between what might be expected and what actually occurs. Fielding’s target for fully exploiting the device of irony in Tom Jones is to delineate characters’ behavior and conduct. Fielding’s technique sheds light on the significance of irony end underlines the fact that language is not merely an inflexible conveyer of information but rather the reader’s mind has to be more flexible end capable of grasping shades of meaning. Fielding’s technique of irony also destabilizes the reader’s assurance of his unscrutinized notions. It is the attitudes of the reader as much as those of the characters that are being subject to examination by the novelist (see Le Boeuf, 2007; Gibbs, 1994; Attardo, 2000; Chen, 1990; Barbe, 1995; Kruez and Roberts, 1993; Clark and Gerrig, 1984).

Irony is largely exploited and the distinction between ‘love’ and ‘lust’ is also voiced throughout the book. ‘Justice’ and ‘mercy’ as abstract values are also examined. The shifts in the narrative voice impels the reader to derive information either, from relying completely on the narrator or, from depending upon his own potentials for measuring the value of the narrator’s claim, to know a particular fact or not. Empson (1982, p. 142) indicates that double irony is a means through which, the narrator, instead of adopting one level of meaning by exposing the flaws in another, ‘may hold some wise balanced position between them, or contrariwise may be feeling a plague on both your houses. Empson seems to initiate a third indicator, namely ‘qualified irony’ in which, the narrator asserts that there is merit on both sides which, is one method of explaining the prudence of Mrs. Adams. Thus we can say that the basis of judgment of characters is gone under complex attempts. Levine (1996, p. 79) views irony in Tom Jones as a means of satirtic characterization. He concentrates on the way through which the characters are presented, but my concentration will be on the way through which, the nature of the characters is unfolded. Their nature shares some aspects of the reader’s nature and thus the reader is invited implicitly to re-evaluate and perfectly judge the real aspects and qualities of the characters themselves as well as those of himself (see Kruez and Glucksberg, 1989; Brown, 1980; Mao, 1991; Glucksberg, 1995; Myers, 1977; Giora, 1995, 1997; Giora et al., 1997; Amante, 1981).

Irony is one of the four kinds of humour which might be operational in a fictional world. Satire, romance and farce are also regarded as types of humour. The difference among the four kinds could be reflected in the actions they represent. Lang (1983) says that farce emphasizes a kind of comedy characterized by loud, noisy and rough behavior. It leaves people at its end as they were at its beginning. The repetition which the farce suggests is the point which increases attraction to it. Romance often brings agreements in feelings, always in the form of marriage. Satire suggests ridicule and a form of mockery aiming to bring about a conflict. While farce depends upon the physical use of power and romance upon hopes and expectations, satire is designed to serve its end without elaboration.

Irony has a doubling effect, a surface level and a real depth, weakness and strength, affirmation and denial, all are included within an ironic view. The doubling effects of irony are forced on the investigator and it is his part to recognize the hidden ground. Irony is the major form of humour found in Fielding’s discourse of his classics. Leech (1981) says, basing his view on Booth’s (1974) ideas that irony represents some kind of ‘secret communion’ between the author and the reader. In case that such communion is undermined, then it is to be the author’s inability to bring the reader in line with him, and not the reader’s deficiency to comprehend the values presented by the author. Irony which represents contrasts in values within the framework of two different viewpoints could take place either in one sentence or in a comprehensive work. To depict the heroes and their companions with these changes in their characters, the author has employed ironic devices in his work to illuminate it. The importance of employing ironic techniques is to set up two opposite meanings for reinforcing the style and for urging the readers to understand properly the characters’ behavior.

Fielding’s Tom Jones, which is built on satire, tackles also two important concepts namely, charity and chastity, and it is through connotations of meaning that the author makes it difficult for the readers to make a simple judgment and thus complications arise for the evaluation of characters. Some puzzling questions are set up; do mercy, compassion and forgiveness contradict justice or not? But whether they contradict justice or whether they do not, are they regarded as virtues or vices? Do mercy, compassion, and forgiveness cause harm or reconcile? The problem is incorporated in the fact that the Christian religious doctrine asks for forgiveness, while the laws of justice ask for punishment; a culprit should get his deserts. The problem is also incorporated in the fact that it is difficult to know which cases deserve forgiveness and compassion and which do not. Those who wish to be charitable with either encourage vice and infringe the laws of justice or fulfil the laws of justice and condemn others. In both cases, no assertions of judging correctly are underscored as long as the evidence is not sufficient to communicate the truth. A judge has to avoid hasty judgment as long as judgment constitutes a major significance. He has to judge not only in accordance with the laws of justice but also in accordance with the laws of the religious doctrine.

Finally, Hume (2010, p. 260) made it clear that if we are trying to make sense of literature as it was written in the middle of the eighteenth century, we have to understand that most authors—Fielding prominent among them—genuinely wanted to change the thinking and behaviour of their readers. They attempted to influence specific attitudes and actions relative to particular events, persons, and ideas, as well as more general loyalties. They sought to persuade—in personal, moral, and political terms. Battestin (1989) concurred in finding Fielding “fundamentally a moralist”, but he insisted that “what is most memorable about Fielding is not his morality or his religion, but his comedy—the warm breath of laughter that animates his fiction”. Fielding’s writing is didactic but it is not preaching and there is a major difference. Fielding unquestionably has “designs” upon the reader: he almost always writes with conscious instructional purpose, not just for entertainment. He presents us with “realistic” lives and characters—realistic in his terms, not in ours—and he means us to sympathize, criticize, enjoy, and ultimately judge. Fielding has enormous bounce and humour and high spirits, but he is a profoundly didactic writer.

Fielding’s characters in Tom Jones

The demonstration of characters is a two-edged weapon; it gives the narrator the freedom to expose specific moral or ethical considerations, in addition to expressing implications and restraining information, which affect the judgement of the reader. Actions and situations also contribute to defining the nature of certain concepts, such as charity and chastity. Fielding’s characters are considered flat or,that is, static that they have no ‘convincing inner life’. They do not change or enhance the course of events of the story. Fielding seems to be a close associate to Aristotle and Horace, as regards the flatness of characters. He proclaims that actions: “Should be likely for the very actors and characters themselves to have performed; for what may be only wonderful and surprising in one man, may become improbable, or indeed impossible, when related to another … This requisite is what dramatic critics cell conservation of character, and it requires a very extraordinary degree of judgement” (Fielding’s Tom Jones, BK viii, Ch. 1, p. 366).

Fielding is less inclined to describe the psychology of the characters but rather the qualities and peculiarities of them. Sometimes flat characters are described in a way which could not be mistakenly understood. For instance, it is stated that “Allworthy was, and will here after appear to be, absolutely innocent of any criminal intention whatever, ‘which is one way describing an aspect of Allworthy’s character to be fully perceived by the reader”. In other cases, flat characters add complications to the reader’s response, such as those described as ‘notorious rogues’ or ‘abandoned jades’, because in these cases, it is the reader’s assumption of the qualities of the characters that is subject to change. Obviously, flat characters do not change or develop but rather it is the reader’s perception of them that changes. Early in the book, the narrator makes fun of epithets given to persons, in accordance to one’s needs. On blaming Jenny Jones for having a bastard son, she is described by Mrs. Deborah Wilkins as "a very sober girl” and by the housekeeper as an “audacious strumpet”. Bridget on the other hand, states that she is one of those "good, honest, plain girl(s)" who are deceived by wicked men. Despite, Wilkins’ previous condemnation of Jenny’s attitude, she agrees with her mistress in her characterization. Referring to epithets to characterize the nature of persons, serves as a means of measurement and judgment. Sometimes the public judgment aligns that of the narrator, as is the case when Bilfil exposes the illicit catch incident of Tom and Black George?: “When this story became public, many people differed from Square and Thwackum in judging the conduct of the two lads on the occasion. Master Bilfil was generally called a sneaking rascal, a poor-spirited wretch; with other epithets of the like kind; whilst Tom was honoured with the appellations of a brave lad, a jolly dog and an honest fellow” (Fielding’s Tom Jones, BK 111, Ch. 5, p. 134).

A different evaluation of the public is suggested later and it is Sophia’s perception which maintains that "To say the truth, Sophia, when very young, discerned that Tom, though an idle, thoughtless, rattling rascal, was no-body’s enemy but his own and that Master Bilfil, though a prudent, discreet, sober, young gentleman, was at the same time, strongly attached to the interest only of one single person; and who that single person was, the reader will be able to divine without any assistance of ours" (Fielding’s Tom Jones, BK iv, Ch. 5, p. 162). Epithets in the above-mentioned quotation are made obvious through inherent irony. Epithets also mirror the evaluation of the community. Tom at the age of twenty is called a "pretty fellow among the woman in the neighborhood; Allworthy when he dismisses Tom from his household is an "inhuman father"; Square is "what is called a jolly fellow or a widow’s man”. These epithets give the reader information which aids him in attempting judgment. Refraining from giving complete information about the characters evokes not only misconception among the characters themselves, but also misunderstanding about the characters in the reader’s eyes. This is the case of Jenny Jones or Mrs. Waters. Her character is a little bit conserved as long as, it is not completely unfolded as Allworthy’s or Tom’s. Actions undertaken by the character’s work consistently with their natures. Black George, for example, attempts to take possession of the five-hundred-pound note extended from Allworthy to Tom when banished from Allworthy’s house. When Black George has met Tom after being dismissed, he is anxious lest Tom asks to borrow some money although "he had … amassed a pretty good sum, in Mr. Western’s service”. In a further, situation, he gives Tom a sum of money amounting to sixteen guineas, sent by Sophia to him, because if he attempts to pocket the sum as he has done in the previous case, the matter will be unfolded; thus "by the friendly aid of fear, conscience obtained a complete victory in the mind of Black George”. George’s ingratitude to Tom is apparent, although Tom in return attempts to save his family from starvation.

In a further situation, the reader as much as Tom doubts George’s behaviour on meeting Partridge in London and knowing that Bilfil is coming to town in pursuit of Sophia to marry her. Partridge in his course of conversation with George, hints at Tom’s relationship with Bellaston and when Tom accuses Partridge of’ betraying him, he confirms George’s loyalty: "I can assure you, George is sincerely your friend, and wished Mr. Bilfil at the devil more than once; nay, he said he would do anything in his power upon earth to serve you” (Fielding’s Tom Jones, BK xv, Ch. 12, p. 737). Partridge seems to know little about George in comparison either with Tom or with the reader. George appears in a different air, near the end of the book. The reader seems to forgive him from his previous lapses, as when Tom has been imprisoned and George has been acquainted with reports among the Westerns, that Tom is about to be hanged; George appears of a “a compassionate disposition”, rapidly offers services and money to Tom and quickly brings news about Sophia to Tom. Empson is puzzled by such narrative shift: “No doubt we are to believe the details, but Fielding still feels free, … to give a different picture of the man’s character at the other end of the novel; I take it be refused to believe that the "inside" of a person’s mind … is much use for telling you the reel source of his motives” (Empson, 1982, p. 135).

It is only through full cognizance of the inside of a person’s mind, that one is being acquainted with that person’s motives. The theme of the novel, however, suggests that the outward appearance of a person could lead to delusion and it is the prudence and the acute insight of the reader that unravel connotations. It is through reduced information that the reader makes evaluation; that is why Black George is seen in two contradictory extremes in the reader’s eyes. Therefore, it is not the character of George, which changes but rather the reader’s evaluation in the light of the given information that changes. Partridge is also introduced as flat character; at first he is seen as a learned, good-natured and a successful school master; “... tho’ this poor men had undertaken a profession to which learning must be allowed necessary, this was the least of his commendations" (Fielding’s Tom Jones, BK, 11, p. 91). The last sentence in the quotation maintains inherent meaning, either learning is among other professions that are worthy of commendation or his learning is terribly ranked. This irony, of course, does not reflect directly the narrator’s view of Partridge. A little bit later, he is seen afraid of his wife. His motives when the reader has met him at Hambrook presents him in a different view, he wishes to accompany Tom in his military pursuit, in which, he sees an opportunity to persuade Tom to come back home in order to gain a reward from Allworthy. Later his cowardice is reaffirmed, when he is afraid to take part in the battle between Tom and Northerton to rescue Mrs. Waters. He is seen shivering on his knees, afraid of being shot by the highwayman. He is also afraid of a ghost, which has been participating in the performance of Hamlet.

A different presentation of Partridge is celebrated, suggesting that his probity and adherence to moral codes are not so far underscored. This presentation is maintained when he offers to borrow two horses from an inn, "now as the honesty of Partridge was equal to his understanding, and both dealt only in small matters, he would never have attempted a roguery of this kind, had he not imagined it altogether safe". In spite of Partridge’s early presentation in the book, he is revealed to be neither honest, nor charitable, in addition to being a coward and an opportunist, who sees that accompanying Tom to convince him to return home, is a chance to win a reward from Mr. Allworthy. When Partridge realizes in London that Tom has entirely no money, he urges him to break his relationship with Sophia and return to Allworthy. Such an attitude does not suggest his selfish motives, as much as his good nature: “… that Partridge, among whose vices ill-nature or hardness of heart were not numbered, burst into tears; and after swearing he would not quit him in his distress, he began with the most earnest entreaties to urge his return home. "For Heaven’s sake, sir’, says he, ’do but consider … How is it possible you can live in this town without money? Do, what you will, sir, or go wherever you please, I am resolved not to desert” (Fielding’s Tom Jones, BK XIII, Ch. 6, p. 629).

Just as it is revealed late in the book that Black George has a "compassionate disposition", it is the same, that Partridge is not ill-natured or hard-hearted, but good natured as was proposed by the narrator, early in the book. The scenes, in which Partridge appears, shed no light on his good nature, as when he rejects to give a shilling to a lame beggar. He seems to be interested in financial affairs. He is desirous to know the amount of money given to Tom by Allworthy, and he is less inclined to extend his own money to Tom in an attempt, either to impel Tom to use Sophia’s bank note or return home. A distinguishing feature of Partridge’s character is feelings of devoted attachment and affection to Tom. He insists to keep by Tom’s side, not merely for reasons of self-interest.

Described as ‘faithful servant’, Partridge was greatly frightened at not hearing from his master so long, when Tom has been put in jail for wounding Fitzpatrick. The narrator’s earlier definition of Partridge and the reader’s evaluation of him are discovered to be both inadequate. Partridge’s dishonesty is rebuked in the reader’s eyes, yet it is only in one instance that his dishonesty is praised; when he attempts to conceal the truth from Allworthy lest he knows that Tom and his mother have committed incest ignorantly. The label that suggests Partridge to be an ‘honest fellow’ does not strictly speaking suggest that he is honest, nor does it indicates him to be dishonest. Each case has its own justifications. The epithet ‘honest fellow’ resembles that given in the introduction, that he is ‘one of the best-natured fellows in the world. The context emphasizes the opinion of the world rather than that of the narrator. The character of Partridge is displayed, to be neither so good, nor so bad. In both the cases of Partridge and Black George, there are inconsistencies; the characters are presented in a certain view, contrasted a little bit later by another appearance. However, the narrator aims at concealing information which influences the reader’s judgment, and in the meantime exhibits new evidence which destablizes the reader’s former response, suggesting inadequacy.

Nightingale who appears at the very end of the book is introduced as one of those "men of wit and pleasure about town", who devote their more serious hours to criticizing new plays, writing love poems, gaming, hack-writing and considering of methods to bribe a corporation"· The narrator confirms that he was a modern fine gentleman "only … by imitation, and meant by nature for a much better character". When the reader next meets him he is presented in a different air, seems to be a niggard. When Tom is acquainted with the terrible situation of Mrs. Miller′s cousins, he offers fifty pounds to relieve their distress, while Nightingale, not acquainted with Tom’s offer, states, "I will give them a guinea with all my heart”.