Abstract

Introduction

Coming out as gay can be a psychologically challenging event, and recall of a negative coming out experience can initiate subsequent identity changes in gay men. We tested whether baseline levels of identity resilience and internalized homonegativity moderate these effects.

Methods

A between-participant experimental study, with an ethnically diverse sample of 333 gay men in the United Kingdom (UK), examined levels of contemporaneous identity threat of reflecting upon recollections of either a coming out experience that had a negative or a stabilizing effect on self-schema. Data were collected in 2020 and analyzed using multiple regression and path analysis.

Results

Path analysis showed that a model predicting level of identity threat after recall of a negative coming out experience fitted the data well. Identity resilience was negatively correlated with internalized homonegativity and distress during memory recall. Both distress and homonegativity correlated positively with identity threat. The relationship between recalling a negative coming out experience and distress was mediated by the perceived typicality of the recalled experience.

Conclusions

Through its effects on distress and internalized homonegativity, identity resilience reduces the threatening effect of recollecting a negative coming out experience upon contemporary identity.

Policy Implications

Offering gay men awareness of the social and psychological routes to raising identity resilience may be beneficial in reducing internalized homonegativity and the ongoing effects of remembered negative coming out experiences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This article focuses on the impact of recalling a significant “coming out” experience (disclosure of one’s gay identity to others) for identity processes in a sample of gay men in the United Kingdom (UK). There has been research into the impact of coming out among gay men in a variety of cultural contexts, much of which shows the adverse psychological impact of coming out in homonegative social contexts (e.g. Ryan et al., 2015). This is especially the case for gay men who themselves exhibit internalized homonegativity (Brown & Trevethan, 2010; Jaspal et al., 2019), that is, the “direction of negative social attitudes [about their sexual orientation] toward the self” (Meyer & Dean, 1998, p. 161). However, there has been no experimental research among gay men in the UK examining the impact on identity threat of recalling an experience of coming out to someone significant. Furthermore, no research has hitherto examined the potential protective role of identity resilience among gay men who are at risk of negative affect, such as distress, and identity threat. This study begins to address this lacuna by examining the psychological impact of recalling a significant coming out experience in an ethnically diverse sample of gay men in the UK.

Identity Threat and Identity Resilience

This study draws on identity process theory (IPT) (Breakwell, 2001, 2015a, c), which posits that people strive to achieve a sense of identity characterized by self-esteem, self-efficacy, personal continuity, and positive distinctiveness. When these identity principles (which are also sometimes referred to as “motives”, Vignoles et al., 2011) are curtailed due, for instance, to a change in one’s social context, the individual experiences identity threat. Facing a negative reaction from someone significant when coming out as gay is likely to result in identity threat (Jaspal & Siraj, 2011).

People engage in varied types of activity operating at the intra-psychic, through to the interpersonal, group, intergroup, and societal levels in order to achieve personally satisfactory levels of the identity principles and, indeed, to protect them from threat—both pre-emptively and reactively (Breakwell, 2015b; Chryssochoou, 2014; Jaspal, 2019; Lyons, 1996). It is noteworthy that, although the four identity principles are distinct, under some circumstances they do tend to be correlated (Breakwell & Jaspal, 2021). For instance, having a negative experience of disclosing an important element of identity, such as one’s sexual orientation, may plausibly challenge all of the identity principles simultaneously, given that this can cause identity uncertainty, low self-esteem and negative distinctiveness (Bregman et al., 2013; Jaspal & Siraj, 2011; Willoughby et al., 2010). It is therefore reasonable to conceptualize identity threat in terms of perceived reductions to the overall level four identity principles.

Recent developments in IPT (Breakwell & Jaspal, 2021; Breakwell, 2020a, b) have focused upon the concept of identity resilience. Identity resilience is achieved when individuals perceive their identity configuration to be characterized by personally satisfactory levels of self-esteem, self-efficacy, continuity and positive distinctiveness. Identity resilience reflects the subjective belief in one’s capacity to understand and overcome challenges, one’s self-worth and value, certainty of who one is and will remain despite changes that occur in one’s context, and one’s self-construal as positively distinctive from others. Higher self-ratings of these four characteristics reflect greater resilience. Identity resilience reflects the capacity to maintain a stable sense of self against threats. Accordingly, IPT states that the extent to which one’s identity is characterized by self-esteem, self-efficacy, continuity and positive distinctiveness at any one time will significantly influence the capacity to cope with stressors with the potential to threaten identity, such as recalling an adverse reaction to one’s sexual identity disclosure.

Each of the four principles that comprise identity resilience has been shown individually to be instrumental in facilitating favourable coping responses to stressors (Brewer, 1991; Dumont & Provost, 1999; Sadeh & Karniol, 2012). However, the significance of overall identity resilience in influencing such reactions has not been established in gay men. Our study specifically examines the relationship between identity resilience and internalized homonegativity and distress to which gay men who experience a negative coming out experience are susceptible (Ryan et al., 2015; Williamson, 2000).

Recent research into the concept of identity resilience (Breakwell & Jaspal, 2021) has yielded two important findings: first, that identity resilience appears to perform a protective role against negative affective experiences, such as fear; and second, that negative affective experiences that do arise (when levels of identity resilience are low) prompt changes in the perceived contemporaneous levels of the identity principles. The latter point has also been demonstrated in empirical studies of event recall and the self—Ritchie et al., (2016) found that the extent to which recalling a past event was related to positive affect determined the “strength” of identity when it was recalled. In a similar vein, we predict that identity resilience will be inversely associated with distress when recalling a negative coming out experience. Indeed, it has been shown that gay men are especially susceptible to distress in view of negative social representations of homosexuality and coercive heteronormativity (Assi et al., 2020; Williamson, 2000). In this study, distress is defined as a state of emotional suffering characterized by self-focussed negative affective experiences, such as guilt and shame. As such, distress is in turn likely to be positively associated with identity threat.

Psychological Impact of (Internalized) Homonegativity

Since the decriminalization of homosexuality in Britain in 1967, social attitudes have changed significantly and survey studies consistently show that there are generally high levels of endorsement of same-sex relationships in British society (NatCen, 2019). However, sexual minorities do still report facing sexuality-related stigma, often manifested in more subtle ways (Nadal et al., 2016). There has also been some work on the impact of stigma associated with sexual orientation on the psychological wellbeing of sexual minorities, which shows that stigma results in poorer mental health (Meyer, 2003). However, there has been only limited research into the impact of coming out as gay on identity threat, in particular (e.g. Jaspal & Siraj, 2011). As a major stress-inducing experience for many gay men, the impact of coming out on identity threat is an important focus for research.

Existing research shows that stressors, such as victimization, rejection from significant others and homonegativity, increase the risk of depressive symptomatology, including depression, psychological distress, suicidal ideation and self-harm, in sexual minorities (Jaspal et al., 2019; Meyer, 2003). Stressors of this kind may follow a negative coming out experience (D’Augelli, 2002; Igartua et al., 2003; Legate et al., 2012) and, accordingly, are likely to result in identity threat.

Internalized homonegativity has been identified as a common psychological response to exposure to such stressors (Williamson, 2000). Internalized homonegativity refers to the assimilation-accommodation of negative social attitudes toward one’s sexual orientation at a psychological level and can contribute to a devaluation of the self and internal conflicts (Meyer & Dean, 1998). This self-schema constitutes a means of making sense of stigma encountered in one’s social context and its acceptance and incorporation within the identity structure. There is an established empirical link between internalized homonegativity and poor mental health outcomes in gay and bisexual men (Herek & Garnets, 2007), including negative affective experiences, such as distress (Meyer, 2003; Williamson, 2000). However, the implications of internalized homonegativity for identity threat have not yet been studied. As a negative self-hatred psychological schema, which is clearly aversive for self-esteem and positive distinctiveness, internalized homonegativity is likely to be positively associated with identity threat.

Coming Out and Subsequent Recall

In Western societies, such as the UK, coming out is frequently represented as a positive step in one’s social and psychological development and being out as the desirable end state for sexual minority people (Cain, 1991; Ragins, 2004). However, there is also a debate about the significance of coming out (Alonzo & Buttitta, 2019) and of identity labels (Hammack et al., 2019) in a so-called “post-gay” society, that is, in a society where it is assumed that there are high levels of social acceptance and little need to use sexual identity labels for self-definition (Ghaziani, 2011). We contribute to this debate by focusing on the psychological implications of distinct types of coming out experience—those perceived to precipitate some form of negative change vs. those perceived to result in stability.

Sexual minority people are more likely to come out, and to experience better psychological outcomes, in contexts in which their identity authenticity is supported by others (Wells & Kline, 1987). Conversely, hostility and silence from family members can challenge psychological wellbeing in gay men who contemplate coming out to their families (Nordqvist & Smart, 2014). However, an under-explored dimension of coming out is its impact on identity processes among gay men. A negative coming out experience may involve changes in relationships with others (especially significant others, such as one’s parents and siblings), and disruptions to self-esteem and continuity (Ryan et al., 2015; Weinstein et al., 2012). Therefore, we hypothesize that recalling a negative coming out experience is likely to cause feelings of identity threat.

Coming out may be best thought of in terms of a continuum (Mohr & Fassinger, 2000). Developmental stage-based models of coming out focus on the internal psychological and external social factors that shape the coming out experience (e.g. Coleman, 1982; see also Jaspal, 2019). People come out repeatedly as they meet new people. They vary in the extent to which they come out—some continue to discuss their sexual orientation with other people while others never revisit this topic after their initial coming out experience. While positive experiences of coming out can have affirmative outcomes for identity, psychological wellbeing and health outcomes, a negative coming out experience (especially to significant others) can have deleterious effects. The effects may be felt long after the actual coming out experience as individuals recall, or are reminded of, that experience (Ryan et al., 2015). Furthermore, they may be primed to recall the experience when anticipating coming out in the present or future, potentially shaping their decision-making and behavior in relation to coming out (see Meyer, 2003).

The fading affect bias (Ritchie & Batteson, 2013; Walker et al., 2003) refers to the tendency for negative affect, such as distress, to fade more rapidly than positive affect from the occurrence of an event (e.g. a significant coming out experience) to its subsequent recall. The fading affect bias is smaller for events that are subjectively deemed important for identity than for relatively unimportant events (Ritchie et al., 2006). Moreover, events for which there is not yet psychological closure are less susceptible to fading affect bias (Beike & Wirth-Beaumont, 2005; Ritchie et al., 2006). A negative coming out experience is likely to be psychologically significant because it concerns a typically important element of identity. Furthermore, when significant others (e.g. family members) are involved, a negative coming out experience may not be characterized by psychological “closure”.

In their study, Ritchie et al. (2016) found that negative affect associated with event recall was associated with three regulatory identity goals: esteem, continuity and meaningfulness. Ryan et al. (2015) found that recalling a negative coming out experience was related to negative affect but that recalling a positive experience had no discernible effect on affect. However, to understand this relationship further, we examine the potential mediating role of an additional variable which taps into the perceived typicality of one’s coming out experience of one’s overall coming out experiences. After all, a negative coming out experience which is deemed to be more typical is likely to reinforce the view that opposition to one’s sexuality is consensual and commonplace (Jolley & Jaspal, 2020); it may induce uncertainty and fear in relation to future and present, and therefore result in greater feelings of distress (Burgess et al., 2007). We therefore predict that the relationship between recalling a negative coming out experience and distress will be mediated by the perceived typicality of the recalled coming out experience, with greater typicality being associated with greater distress. More generally, this line of thinking is consistent with research showing that distress is prevalent in gay men struggling to assimilate and accommodate their sexual orientation in identity (Bybee et al., 2009; Williamson, 2000).

A Social Psychological Model Explaining Contemporaneous Identity Threat in Gay Men

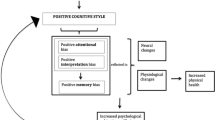

Consistent with IPT (and specifically the concept of identity resilience) and the literature on event recall, internalized homonegativity and negative affect, we propose the following model predicting identity threat in gay men who are asked to recall a significant coming out experience (Fig. 1). The following four specific hypotheses are tested:

-

1.

In comparison to those in the stability condition, participants in the negative change condition will report higher identity threat upon recall of their coming out experience, even when controlling for the effects of internalized homonegativity and distress on identity threat.

-

2.

The relationship between being in the negative change condition and feeling distress upon recall of one’s coming out experience will be mediated by the perceived typicality of the recalled experience, with greater perceived typicality being associated with greater distress.

-

3.

Identity resilience will be negatively associated with both internalized homonegativity and distress upon recall.

-

4.

Both internalized homonegativity and distress following recall will be positively associated with identity threat.

Method

Design

A between-participant experimental study was conducted to examine the effect of recalling the experience of coming out to someone significant which resulted in negative change (negative change condition) vs. that of coming out to someone significant which resulted in things staying the same (stability condition).

Participants

An ethnically diverse sample of 333 gay male participants in the UK was recruited on Prolific (https://www.prolific.co/), a popular online participant recruitment platform in 2020. To be eligible to take part in the study, participants had to be registered on the platform as being aged 18 or over and gay. Table 1 provides the main characteristics of the participant sample. Ethnic diversity in the sample was sought in order to explicitly avoid “White” bias and not in order to be used to examine ethnic differences.

Procedure

All questionnaires were administered and completed online. First, participants completed measures of identity resilience and internalized homonegativity. They were then randomly allocated to one of the following two experimental conditions: half were asked to recall and describe in 2–3 sentences a coming out experience which resulted in negative change (negative change condition) and half a coming out experience that resulted in things remaining the same (stability condition). The manipulation was intended to prime participants to recall, and keep in mind, a noteworthy coming out experience that brought about either negative change or stability. While keeping this specific experience in mind, participants were asked to indicate how typical this experience was of their other coming out experiences and how upset they felt by this particular coming out experience. (The latter was essentially a manipulation check.) They then completed measures of contemporaneous distress and identity threat. Finally, they provided demographic information, including age, self-identified gender, sexual orientation, religion, educational attainment, occupation and income. Participants provided electronic consent, were debriefed and thanked for their time. They were paid a token amount for participating in the study.

Measures

Identity Resilience

The Identity Resilience Index (Breakwell, Fino & Jaspal, 2021) comprising 16 items with responses on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) was used. Items included “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself” and “There is continuity between my past and present”. A higher score indicated higher identity resilience (α = 0.83).

Internalized Homonegativity

The Internalized Homophobia Scale (Herek et al., 2009) comprising 9 items with responses on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all true of me to 5 = very true of me) was used. Items included “I wish I weren’t gay” and “I have tried to become more sexually attracted to women”. A higher score indicated higher internalized homonegativity (α = 0.88).

Typicality of Coming out Experience

Participants was asked to indicate the extent to which the coming out experience they described was typical of their general experiences of coming out on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all typical to 5 = very typical).

Being Upset by the Coming out Experience Recalled

The following four items were used to measure the extent of being upset by the recalled coming out experience, which acted primarily as a manipulation check: “To what extent did this experience upset you at the time?”, “To what extent does remembering this experience upset you currently?”, “To what extent does remembering this experience upset you in general?” and “How often does remembering this experience upset you in general?” The four items were summed, and a higher score indicated feeling more upset by one’s coming out experience (α = 0.87).

Distress

Four items were used to index the extent to which participants were feeling a variety of emotions indicative of distress immediately after they had described a significant coming out experience while they were still completing the questionnaire. Participants indicated the extent (1 = very slightly or not at all to 5 = extremely) to which they were—at that moment—feeling guilty, ashamed, distressed and upset. Ratings of the four feelings were summed, and a higher score indicated feeling more distress (α = 0.81).

Identity Threat

The Identity Threat Scale was created consisting of 4 items (see Appendix) with responses on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all true of me to 5 = very true of me). A higher score indicated higher identity threat (α = 0.78).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics for the main variables in this study.

Correlations

Identity resilience was negatively associated with internalized homonegativity, perceived typicality of one’s coming out experience and distress. Internalized homonegativity was positively associated with feeling upset upon recall of one’s coming out experience, distress and identity threat. Perceived typicality of one’s coming out experience was negatively associated with feeling upset upon recall. Feeling upset upon recall was positively associated with distress and identity threat. Distress was positively associated with identity threat (Table 3).

Differences by Condition (Negative Change vs. Stability) in Pre- and Post-Manipulation Measures

Independent-sample t-tests bootstrapped at 1000 samples indicated no significant differences between those assigned to the negative change and those assigned to the stability conditions on the pre-manipulation measures of identity resilience or internalized homonegativity (p > 0.05).

As regards the post-manipulation measures, further tests showed that participants assigned to the negative change condition reported feeling more upset [t (331) = − 7.98, p = 0.001] and more identity threat [t (331) = − 4.36, p = 0.001] upon recall of their coming out experience than those assigned to the stability condition. They also perceived their recalled coming out experience to be less typical of their general coming out experiences [t (331) = 4.02, p = 0.001] than those assigned to the stability condition. There was no significant effect of the condition on distress.

Table 4 provides a summary of the means, standard deviations, Cohen’s D and 95% confidence intervals.

Multiple-Regression Model Predicting Identity Threat

Stepwise multiple regression was conducted to examine which variables predict the variance of identity threat. Internalized homonegativity, distress and the condition (stability = 0 vs. negative change = 1) were inserted as predictors, and identity threat as the dependent variable.

Internalized homonegativity was entered at step 1 and explained 12% of the variance in identity threat. At step 2, internalized homonegativity and distress explained 20% of the variance in identity threat. R-square change was 0.08, and F-change was 32.95 (p < 0.001). At step 3, internalized homonegativity, distress and the condition explained 26% of the variance in identity threat. R-square change was 0.06, and F-change was 27.95 (p < 0.001). The regression model was statistically significant [F (3, 332) = 39.47, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.26]. Of all predictors, distress with a β = 0.31, S.E. = 0.06, (t = 6.01, p < 0.001) was the most powerful, followed by the condition with a β = 0.25, S.E. = 0.31, (t = 5.29, p < 0.001), and internalized homonegativity with a β = 0.23, S.E. = 0.03, (t = 4.47, p < 0.001). This supports hypothesis 1.

Path Analysis

Path analysis was performed with a bootstrap at 1000 samples with the main predictors of identity resilience and condition (stability = 0 vs. negative change = 1) and the mediators (internalized homonegativity, perceived typicality of the recalled coming out experience, and distress upon recall) to predict the dependent variable of identity threat. Model fit was excellent with χ2 (7, 333) = 3.95, p > 0.05, a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.00, a Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) of 1.03 and a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of 1.00. As depicted in Fig. 2, there were four main pathways to identity threat.

First, identity resilience was negatively associated with distress with a β = − 0.17, S.E. = 0.02, p < 0.05.

Second, identity resilience was negatively associated with internalized homonegativity with a β = − 0.25, S.E. = 0.04, p < 0.001, which in turn was positively associated with identity threat with a β = 0.32, S.E. = 0.02, p < 0.001. There was also a mediation effect. Internalized homonegativity was also positively associated with distress, with a β = 0.37, S.E. = 0.02, p < 0.001, was in turn was positively associated with identity threat with a β = 0.31, S.E. = 0.06, p < 0.001.

Third, being in the negative change condition had a statistically significant positive effect on identity threat with a β = 0.25, S.E. = 0.30, p < 0.001.

Fourth, being in the negative change condition was associated with perceiving the recalled coming out experience as being less typical of one’s general coming out experiences with a β = − 0.22, S.E. = 0.11, p < 0.001, with in turn was positively associated with distress with a β = 0.10, S.E. = 0.13, p < 0.05. As indicated above, distress was positively associated with identity threat. This supports hypotheses 2–4.

Discussion

We examined some of the factors that predict level of identity threat upon recall of a negative coming out experience. All four of the hypotheses that comprise our theoretical model were supported. The results indicate that the act of recalling even an isolated, atypical coming out experience that precipitates negative change has the power to induce identity threat. The data also suggest that negative affect (i.e. distress) and identity threat upon recall may be accentuated by internalized homonegativity but that an additional amount of the variance in identity threat is explained by the experimental condition (i.e. actually recalling a negative experience). This would appear to be consistent with the minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003, p. 675), which highlights “the excess stress to which individuals from stigmatized social categories are exposed as a result of their social, often a minority, position”. Stressors, such as homonegativity, rejection and victimization, to which gay men may be exposed—albeit to varying degrees—may render the experience of having a (minority) gay identity a threatening one (Breakwell, 2015a) and may in turn accentuate the adverse psychological effects of recalling even an atypical negative coming out experience (cf. Ritchie & Batteson, 2013). More generally, our findings demonstrate the psychological significance of coming out and of using sexual identity labels such as “gay” in contemporary gay society (cf. Alonzo & Buttitta, 2019).

Our theoretical model predicting perceptions of current identity threat that is aroused by being asked to recall and describe an experience of coming out to a significant other was supported by the path analysis. The experimental manipulation entailed asking participants to recall a coming out experience that resulted in a negative change in their lives or one that resulted in something staying the same. The model predicts the experimental condition will have a direct effect on identity threat, and it did: threat was greater if the recall involved negative change (Ritchie et al., 2016). It is notable that we compared a negative change with stability. Had we compared a negative change with a positive change, we might have expected an even greater disparity in the impact on identity threat. Identity threat was indexed in terms of perceived current challenge to the four identity principles described in IPT (self-efficacy, self-esteem, continuity and positive distinctiveness). It is worth emphasizing that the measure of identity threat was focussed upon the challenge to identity at the time of the experiment from recall of coming out events in the past. We did not ask participants to say how much identity threat they experienced immediately following the coming out experience.

As hypothesized, there was an indirect effect of recalling a negative coming out experience and distress through perceived typicality of the recalled experience. More specifically, perceiving a negative experience to be more typical of one’s overall coming out experiences (perhaps because it is perceived to be common) was associated with increased distress upon recall. This would suggest that perceiving negative coming out experiences to be commonplace in one’s life may compromise psychological wellbeing (manifested in our study as distress) upon recall of a negative coming out experience. This may be rooted in the perception that one’s sexuality is not accepted by others (especially by significant others) and that one’s value as a gay man is thus questionable and in the possible anticipation of negative experiences upon future sexual identity disclosure (Ryan et al., 2015; Weinstein et al., 2012). The latter has been referred to as hypervigilance and is characterized by negative psychological outcomes, such as avoidance behaviours (Jolley & Jaspal, 2020). Incidentally, this line of thinking is also consistent with the empirical observation in our study that internalized homonegativity is positively associated with both distress and identity threat.

In contrast to previous work which has examined the collective impact of esteem, continuity and meaningfulness on decreasing negative affect while recalling a past memory (Ritchie et al., 2016), identity resilience is a measure of the combined strength of the four identity principles which represent a broader conceptualization of selfhood, including self-efficacy and distinctiveness (Breakwell, 2015a). It was expected to affect the amount of current identity threat experienced through influencing the extent of internalized homonegativity and negative affect aroused by recall of the experience. This was found to be the case. Identity resilience is negatively related to internalized homonegativity and distress upon recall. This suggests that identity resilience may be protective against negative cognitive and affective states, such as internalized homonegativity and distress, which are in turn associated with the onset of identity threat (Breakwell, Fino & Jaspal, 2021).

The internalized homonegativity measure, which was taken prior to the introduction of the experimental condition and thus is not influenced by it, was hypothesized to be a direct predictor of current identity threat. This was the case. Internalized homonegativity, in part, reflects the contemporaneous inability of the assimilation-accommodation and evaluation processes of identity to comply with the identity principles of self-esteem, self-efficacy, continuity and positive distinctiveness. Since internalized homonegativity represents a negative self-schema (i.e. that being gay is a flaw in one’s identity), the assimilation-accommodation and evaluation of being gay are unlikely to produce satisfactory levels of the identity principles, resulting in identity threat (Breakwell, 2015a, b, c). In addition, greater internalized homonegativity was hypothesized to be positively associated with distress generated during recall of the coming out experience. This proved to be so. Finally, higher distress associated with the recalled experience was predicted to lead to greater identity threat, which was supported in the data.

The pivotal role of internalized homonegativity in this model should not be underestimated. As measured in this study, internalized homonegativity is focused upon feelings of dissatisfaction with being gay. Various factors have been shown to increase the risk of internalized homonegativity, such as prejudice, shame and group memberships perceived to be incompatible with one’s sexuality (Jaspal, 2019; Williamson, 2000). No research has previously examined the potential protective effect of identity resilience. Our data show that identity resilience was significantly negatively correlated with internalized homonegativity, supporting this hypothesis. Internalized homonegativity may be a cipher for ambivalence about gay identity and, as a consequence, when faced with recalling a negative coming out experience, may be intensifying both negative emotions (i.e. distress) and threat to current identity.

The effectiveness of the experimental manipulation in surfacing perceived contemporary identity threat is notable. Simply recalling and describing a negative change concomitant upon a coming out experience triggers feelings of reduced self-worth, competence and uniqueness besides increased pressure for change. The extent of this change is enhanced by the negativity of the emotion aroused by the memory and the level of pre-existent internalized homonegativity felt. This further clarifies the fading affect bias (Ritchie & Batteson, 2013; Walker et al., 2003), which would suggest that negative memories fade more rapidly—existing internalized homonegativity may play a key role in accentuating the effect of the negative memory on contemporary affect and identity processes.

One key contribution this study makes is to emphasize the continuing potency of negative experiences as part of coming out. This potency is manifest in both the emotion that is aroused during recall and recounting of the experience and in its ability to precipitate perceived changes in current identity. A further contribution the study makes is to illustrate that prior identity resilience is related to a less negative emotional reaction, and this militates against current identity threat. Consistent with other recent work in this area (Breakwell & Jaspal, 2021), the results suggest that identity resilience performs a protective function against negative affect and identity threat. It may therefore constitute a useful construct for psychological practitioners working with gay men who are experiencing, or at risk of, decreased psychological wellbeing due to sexuality-related minority stress.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has some limitations which should be addressed in future research. First, it will be important to extend the study to a larger and more representative sample in the future. Although we recruited an ethnically diverse sample, the relatively small subsamples of ethnic minority individuals (e.g. those of Indian heritage vs. those of Black Caribbean descent) precluded the analysis of group differences. This would be a worthwhile focus of future research. Second, the study examined the effects of recall of negative and stability experiences during coming out. It did not explore the effects of recall of positive experiences. This shifts the emphasis of the study toward the more damaging aspects of the process of coming out. Since the objective was to explore identity threat, this seemed reasonable. However, it would be advantageous to replicate the study using the recall of positive experiences of coming out. Third, we focused on distress as an indicator of negative affect because in previous research it has been shown to be relevant to the experience of gay men. Future work ought to examine other potentially relevant indicators of negative affect, such as guilt and shame, as well as those of positive affect, such as pride.

Social and Policy Implications

Some conclusions that can be drawn from this study have social and policy implications. The findings indicate that identity resilience is a useful predictor of emotional response to recalled negative experiences, and that negative affect is associated identity threat reflected in perceived changes across four elements of the self-schema (self-esteem, self-efficacy, continuity and distinctiveness). The insidious effects of internalized homonegativity are evident. It accentuates both distress and identity threat upon recall. Perceiving a negative coming out experience to be typical (perhaps because it actually is) is associated with greater distress upon recall. Distress and identity threat following recall are related. The findings indicate the potentially lasting effects of a negative coming out experience, with those who recall it reporting higher identity threat and (through perceived typicality of the recalled experience) higher distress.

Bridging IPT and minority stress theory, our findings suggest that recall of a negative coming out experience may be sufficient to compromise psychological wellbeing among gay men. Conversely, recalling a coming out experience that resulted in stability was associated with higher psychological wellbeing. There may therefore be merit in the directed recall of positive events in relation to coming out among gay men in therapeutic settings. This may serve to offset the psychological adversity that is clearly generated by the recall of negative coming out events. Such directed recall may function as a form of personal empowerment for gay men who may be struggling to assimilate and accommodate their sexuality in identity. Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that identity threat is not avoidable—it will inevitably occur over the life-course but the objective must be to enable people to manage threats to identity in effective, proactive and sustainable ways. In fact, some threats to identity may even be harnessed to promote positive change in identity and in one’s broader social context. Our data suggest that identity resilience is a core construct for facilitating the effective management of threats to identity.

Social and policy initiatives to challenge homonegativity in all its guises, and to promote more favourable conditions for coming out, are essential. These must be cognisant of the evolving nature of prejudice and especially “micro-aggressions” which may increase the risk of internalized homonegativity and have insidious effects for identity processes. Importantly, innovative approaches to reducing the risk of internalized homonegativity among gay men, would be advantageous in reducing distress and identity threat. Interventions to promote feelings of identity resilience, which may be a buffer against the negative psychological effects of negative coming out experiences, would be beneficial. Counselling and psychotherapy for gay men struggling with sexual identity issues may focus on developing a greater sense of identity resilience in clients, given its association with decreased threat and more effective coping, using techniques from cognitive-behavioural therapy whose aim is to change maladaptive patterns of thinking and behaviour (Jaspal, 2018). Furthermore, social prescribing approaches (e.g. Husk et al., 2016) that can facilitate the acquisition of social support may help build feelings of identity resilience in gay men.

Availability of Data and Materials

The dataset can be accessed by contacting the corresponding author.

References

Alonzo, D. J., & Buttitta, D. J. (2019). Is “coming out” still relevant? Social justice implications for LGB-membered families. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 11(3), 354–366.

Assi, M., Maatouk, I., & Jaspal, R. (2020). Psychological distress and self-harm in a religiously diverse sample of university students in Lebanon. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 23(7), 591–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2020.1788524

Beike, D. R., & Wirth-Beaumont, E. T. (2005). Psychological closure as a memory phenomenon. Memory, 13(6), 574–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210444000241

Breakwell, G. M. (2001). Social representational constraints upon identity processes. In K. Deaux & G. Philogène (Eds.), Representations of the Social: Bridging Theoretical Traditions (pp. 271–284). Blackwell Publishing.

Breakwell, G. M. (2015a). Coping with threatened identities. Psychology Press, Taylor & Francis.

Breakwell, G. M. (2015b). Risk: Social psychological perspectives. In J. D. Wright (eds), The International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.) (pp.711–716). Elsevier.

Breakwell, G. M. (2015c). Identity process theory. In G. E. Sammut, E. E. Andreouli, G. E. Gaskell, & J. E. Valsiner (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Social Representations (pp. 250–266). Cambridge University Press.

Breakwell, G. M. (2020a). In the age of societal uncertainty, the era of threat. In D. Jodelet, J. Vala, & E. Drozda-Senkowska (Eds.), Societies under threat: A pluri-disciplinary Approach (pp. 55–74). Springer-Nature.

Breakwell, G. M. (2020b). Mistrust, uncertainty and health risks. Contemporary Social Science, 15(5), 504–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2020.1804070

Breakwell, G. M., Fino, E., & Jaspal, R. (2021). The Identity Resilience Index: Development and validation in two samples from the United Kingdom. Under review.

Breakwell, G. M., & Jaspal, R. (2021). Identity change, uncertainty and mistrust in relation to fear and risk of COVID-19. Journal of Risk Research, 24(3–4), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1864011

Bregman, H. R., Malik, N. M., Page, M. J., Makynen, E., & Lindahl, K. M. (2013). Identity profiles in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: The role of family influences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(3), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9798-z

Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(5), 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167291175001

Brown, J., & Trevethan, R. (2010). Shame, internalized homophobia, identity formation, attachment style, and the connection to relationship status in gay men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 4(3), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988309342002

Burgess, D., Tran, A., Lee, R., & van Ryn, M. (2007). Effects of perceived discrimination on mental health and mental health services utilization among gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender persons. Journal of LGBT Health Research, 3(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15574090802226626

Bybee, J. A., Sullivan, E. L., Zielonka, E., & Moes, E. (2009). Are gay men in worse mental health than heterosexual men? The role of age, shame and guilt, and coming-out. Journal of Adult Development, 16(3), 144–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-009-9059-x

Cain, R. (1991). Relational contexts and information management among gay men. Families in Society, 72(6), 344–352.

Chryssochoou, X. (2014). Identity processes in culturally diverse societies: How is cultural diversity reflected in the self? In R. Jaspal & G. M. Breakwell (Eds.), Identity process theory: Identity, social action and social change (pp. 135–154). Cambridge University.

Coleman, E. (1982). Developmental stages of the coming-out process. American Behavioral Scientist, 25(4), 469–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276482025004009

D’Augelli, A. R. (2002). Mental health problems among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths ages 14 to 21. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7(3), 433–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104502007003010

Dumont, M., & Provost, M. A. (1999). Resilience in adolescents: Protective role of social support, coping strategies, self-esteem, and social activities on experience of stress and depression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28, 343–363. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021637011732

Ghaziani, A. (2011). Post-gay collective identity construction. Social Problems, 58(1), 99–125. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2011.58.1.99

Hammack, P. L., Frost, D. M., & Hughes, S. D. (2019). Queer intimacies: A new paradigm for the study of relationship diversity. Journal of Sex Research, 56(4–5), 556–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1531281

Herek, G. M., & Garnets, L. D. (2007). Sexual orientation and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 353–375. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091510

Herek, G. M., Gillis, J. R., & Cogan, J. C. (2009). Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 32–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014672

Husk, K., Blockley, K., Lovell, R., Bethel, A., Lang, I., Byng, R., & Garside, R. (2016). What approaches to social prescribing work, for whom, and in what circumstances? A realist review. Health and Social Care in the Community, 28(2), 309–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12839

Igartua, K. J., Gill, K., & Montoro, R. (2003). Internalized homophobia: A factor in depression, anxiety, and suicide in the gay and lesbian population. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 22(2), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2003-0011

Jaspal, R. (2018). Enhancing sexual health, self-identity and wellbeing among men who have sex with men: A guide for practitioners. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Jaspal, R. (2019). The social psychology of gay men. Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27057-5

Jaspal, R., Lopes, B., & Rehman, Z. (2019). A structural equation model for predicting depressive symptomatology in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic lesbian, gay and bisexual people in the UK. Psychology and Sexuality. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2019.1690560

Jaspal, R., & Siraj, A. (2011). Perceptions of ‘coming out’ among British Muslim gay men. Psychology and Sexuality, 2(3), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2010.526627

Jolley, D., & Jaspal, R. (2020). Discrimination, conspiracy theories and pre-exposure prophylaxis acceptability in gay men. Sexual Health, 17(6), 525–533. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20154

Legate, N., Ryan, R. M., & Weinstein, N. (2012). Is coming out always a “good thing”? Exploring the relations of autonomy support, outness, and wellness for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(2), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611411929

Lyons, E. (1996). Coping with social change: Processes of social memory in the reconstruction of identities. In G. M. Breakwell & E. Lyons (Eds.), International series in social psychology. Changing European identities: Social psychological analyses of social change (p. 31–39). Butterworth-Heinemann.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Meyer, I. H., & Dean, L. (1998). Internalized homophobia, intimacy, and sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men. In G. M. Herek (Ed.), Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals (pp. 160–186). Sage Publications.

Mohr, J. J., & Fassinger, R. E. (2000). Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 33(2), 66–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2000.12068999

Nadal, K. L., Whitman, C. N., Davis, L. S., Erazo, T., & Davidoff, K. C. (2016). Microaggressions toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and genderqueer people: A review of the literature. Journal of Sex Research, 53(4–5), 488–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1142495

NatCen (2019). Over the rainbow? https://www.natcen.ac.uk/blog/over-the-rainbow

Nordqvist, P., & Smart, C. (2014). Troubling the family: Coming out as lesbian and gay. Families, Relationships and Societies, 3(1), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674313X667380.

Ragins, B. R. (2004). Sexual orientation in the workplace: The unique work and career experiences of gay, lesbian and bisexual workers. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 23, 35–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(04)23002-X

Ritchie, T. D., & Batteson, T. J. (2013). Perceived changes in ordinary autobiographical events’ affect and visual imagery colorfulness. Consciousness and Cognition, 22(2), 461–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2013.02.001

Ritchie, T. D., Skowronski, J. J., Wood, S. E., Walker, W., & R., Vogl, R. J., & Gibbons, J. A. (2006). Event self-importance, event rehearsal, and the fading affect bias in autobiographical memory. Self and Identity, 5(2), 172–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860600591222

Ritchie, T. D., Sedikides, C., & Skowronski, J. J. (2016). Emotions experienced at event recall and the self: Implications for the regulation of self-esteem, self-continuity and meaningfulness. Memory, 24(5), 577–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2015.1031678

Ryan, W. S., Legate, N., & Weinstein, N. (2015). Coming out as lesbian, gay, or bisexual: The lasting impact of initial disclosure experiences. Self and Identity, 14(5), 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2015.1029516

Sadeh, N., & Karniol, R. (2012). The sense of self-continuity as a resource in adaptive coping with job loss. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.04.009

Vignoles, V. L (2011) Identity motives. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research: structures and processes. Springer (pp. 403-432). Springer.

Walker, W. R., Skowronski, J. J., & Thompson, C. P. (2003). Life is pleasant—And memory helps keep it that way! Review of General Psychology, 7, 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.7.2.203

Weinstein, N., Ryan, W. S., DeHaan, C. R., Przybylski, A. K., Legate, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Parental autonomy support and discrepancies between implicit and explicit sexual identities: Dynamics of self-acceptance and defense. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 102(4), 815–832. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026854

Wells, J. W., & Kline, W. B. (1987). Self-disclosure of homosexual orientation. Journal of Social Psychology, 127(2), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1987.9713679

Williamson, I. R. (2000). Internalized homophobia and health issues affecting lesbians and gay men. Health Education Research, 15(1), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/15.1.97

Willoughby, B. L. B., Doty, N. D., & Malik, N. M. (2010). Victimization, family rejection, and outcomes of gay, lesbian, and bisexual young people: The role of negative GLB identity. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 6(4), 403–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2010.511085

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by [REMOVED FOR PEER REVIEW].

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the research findings.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix. The Identity Threat Scale

Appendix. The Identity Threat Scale

Please think carefully about the experience you just described. While doing so, please indicate the extent to which you each statement is true of you when you think about this experience.

-

1.

It undermines my sense of self-worth.

-

2.

It makes me feel less competent.

-

3.

I feel that my identity has changed.

-

4.

It makes me feel less unique as a person.

Items are scored as follows: (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Breakwell, G.M., Jaspal, R. Coming Out, Distress and Identity Threat in Gay Men in the UK. Sex Res Soc Policy 19, 1166–1177 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00608-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00608-4