Abstract

The food environment has taken on much of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Evidence shows people's relationship and access to the food environment is a determinant of their health and wellbeing, and in relation to prevalence of chronic and non-communicable diseases. The spatial planning system forms part of a whole systems action in shaping the environment in a way that maximises population health gain. While these practices have had varying degrees of success, the sudden introduction and spread of COVID-19, and the responses to it, has forced us to re-examine the utility of current planning practice, particularly the impact on inequalities. In this commentary we aim to explore the post-pandemic role of spatial planning as a mechanism for improving public health by highlight a whole system perspective on the food environment, referring to experiences in Wales as a case study, and concluding with observation on future consumer trends around access to food.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tackling public health issues associated with non-communicable diseases such as obesity has been the focus of much public health policy prior to COVID-19. Action to tackle chronic disease has influenced the evolution of spatial planning frameworks of nations through using urban planning to shape and organise the built and natural environment in a way that maximises population health gain. Planning for health has benefited how we plan for active travel and transportation, nutrition and sustainable food systems, as exemplified in the UN-Habitat and World Health Organization (2020) publication on health in urban planning. Whilst these practices have had varying degrees of success, the sudden introduction and spread of COVID-19, and the responses to it, has forced us to re-examine the utility of current planning practice, particularly the impact on inequalities (PHE 2020(1); Bambra et al. 2020).

In this commentary, we aim to explore the post-pandemic role of spatial planning as a mechanism for improving public health by highlighting a whole system perspective on the food environment, referring to experiences in Wales as a case study, and concluding with observation on future consumer trends around access to food.

The global burden of disease from dietary risks is high, and in England, Newton et al. (2015) stated dietary risks are the largest contributor to disability-adjusted life year (DALYs)—or life years lost to ill health—in terms of low fruit and vegetables consumption, high processed meat consumption, high sugar-sweetened beverages consumption, high trans-fats intake and high sodium intake. Significant number of adults and children are overweight or obese and a recent Public Health England study highlighted being obese or excessively overweight increases the risk of severe illness and death from COVID-19 (PHE 2020(3)).

People’s dietary behaviour and food consumption patterns can be determined by the spatial organisation of the food environment; how it is licensed, available and accessible to the population, with research indicating a positive association between these spatial structured risk factors and obesity (Burgoine et al. 2014; Townshend and Lake 2017). The Food Foundation (2016) describes the food environment as a dynamic space in which a range of food options for consumers based on food availability, accessibility, affordability and appeal. The exposure of these factors was particularly acute during the height of the lockdown, though the effects continue to be felt with easing of restrictions.

Impact across the whole systems

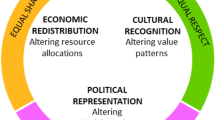

Despite major investment in both science and policy of obesity prevention, limited progress has been made, partly because most effort has primarily been expended on individual-level approaches to modifying obesity-related behaviours rather than population-level structural interventions. In recent years, there has been a focus on the food environment as a key driver of a continuing increase in population obesity and the widening of inequalities in obesity, as well as an increasing recognition of the potential of systems thinking in preventing and treating effects of unhealthy weight (Rutter et al. 2017).

The current pandemic can be seen a major disruption to the normal functioning of the systems that produce obesity, in particular the food system. As a result, there may be lasting short-, medium- and long-term impacts on food system behaviours that may affect population diet and health both positively and negatively. Plausible impacts may be felt on consumer behaviour; food availability, affordability, choice and price; and the structure of urban food retail systems driven by both commercial and consumer behaviour. Disruptions to global supply chains, temporary reductions in food availability due to increased demand and panic-buying, and rises in food insecurity among low-income households have emerged as key immediate challenges during the ongoing crisis (Costa-Font and Revoredo-Giha 2020). In the medium and longer term, the pandemic may induce other changes to the food system such as increasing re-localisation of food retailing and consumer food shopping, accelerating the current transition to digital grocery and takeaway food purchasing and a more fundamental re-structuring and shrinkage of the food environment in response to the impact of the post-pandemic economic environment (Cummins et al. 2020).

Of central importance is the need to monitor the impacts of these inevitable pandemic-related changes to the food system on inequalities in diet and diet-related disease. More disadvantaged households and communities will likely be most affected by post-pandemic changes to the food system. This observation is supported by the Public Health England (2020)(1) review of data on risk of COVID-19 on particularly the Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups.

For example, more affluent households are more likely to be able to take advantage of the transition to online food purchasing given their ability to meet minimum spend, delivery costs and better access to the internet whereas more disadvantaged communities have lower incomes, have greater digital exclusion and are more likely to live in communities where food businesses are less financially viable and are therefore more susceptible to failure. This may facilitate the widening of diet-related health inequalities. All of this presents a challenge to those within planning and public health who are striving to promote a healthier food environment and will be at the frontline of a combination of national and local post-pandemic response.

Impact of COVID-19 on the wider food environment in Wales as a case study

Whilst the focus and impact of COVID-19 and governmental responses to it has been on health, social care and supporting systems, many impacts have not been highlighted to the same extent. This includes the impact in relation to health behaviours such as diet, nutrition and alcohol consumption and the food environment. Political devolution has enabled the four UK nations (England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland) to tackle the pandemic in different ways and this includes their responses to the accessibility of food in and out of the home and food delivery services.

Using Wales as a case study, Public Health Wales (2020) has carried out a Health Impact Assessment (HIA) on the Staying at Home and Social Distancing Policy in Wales. It identified a range of positive impacts and opportunities in relation to food but also negative or unintended negative impacts. A summary of these is in Table 1. It identified a lack of evidence in peer-reviewed academic literature about the effects of quarantine and social distancing policies on people’s behaviour in relation to food and nutrition. In the absence of peer-reviewed evidence, many surveys have been carried out as stated earlier whilst the Staying at Home policy has been applied to start to address that gap, including across Wales.

Positively, the HIA identified that the introduction of the restrictions led to the immediate closure of many fast food outlets and takeaways, although many reopened for delivery services across the UK, including local fast food takeaways and larger businesses with drive-through facilities. It found that more meals have been eaten in the home and this has had an impact on buying behaviours such as food stockpiling. The restrictions have also driven the population to shop more locally and this could have a positive or negative impact on local businesses and future local procurement policies.

These subtle patterns in behaviour change can have short and long-term impacts to health and well-being for children, young people and adults and potentially undermine health and spatial planning policies established to address these pre-COVID-19.

For vulnerable children, governments have ensured that for those children who are eligible for free school meals (FSMs), there are alternative mechanisms by which they can still access food. However, participants in the HIA expressed concern for pupils who were usually eligible for FSMs, and for those whose circumstances had changed so that they were newly eligible for FSMs (for example due to a change in parental employment status). These concerns ranged from food insecurity (particularly access) through to take-up and nutritional quality of FSM replacements, for example, food parcels and the nutritional content of them.

In respect to alcohol use, retail premises permitted to sell alcohol or off-licences have been considered as essential retailers and as a result have been allowed to stay open during the pandemic. With restrictions for licensing and operation eased—this could have a negative impact in making alcohol more accessible with less restrictive opening times. Indeed, the WHO (2020) published a report which highlighted that during the COVID-19 pandemic, movement restrictions could potentially increase alcohol consumption and therefore exacerbate health vulnerability, risk-taking behaviours, mental health issues and domestic violence.

Impact on spatial planning systems on promoting healthier food environments

Medical and public health evidence and guidance has consistently recommended better management the food retail environment through planning (NICE 2010). Spatial planning decisions can help determine people’s health through the way land uses are created, managed and evolve, and how individuals and the whole population interact with them (Blackshaw et al. 2019).

In response to COVID-19 and to manage people’s access to food and drink for those nations imposing social isolation and physical distancing measures, governments such as in the UK have introduced temporary changes to the planning system. The UK Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government has, for example, in March, introduced urgent regulations in March to close all pubs, restaurants and cafes to on-site consumption but through a light touch notification system, allow them to operate takeaway food (UK Parliament 2020), and in Northern Ireland, the Department of Infrastructure issued an advisory to local authorities to provide flexibility to public houses, restaurants and cafes to keep operating. The scale of impact is unknown but there is evidence of both shop closures and some businesses operating in this new way (Savills 2020).

By August, these temporary regulations may have already been lifted, restaurants and pubs have begun to open to the public with social distancing measures and on pavements, and in the public realm, the opening of outdoor markets on closed-off streets encouraged. But these early months of lockdown, and subsequent futher national and localise restrictions, may have prompted irreversible changes to consumer behaviour, and undermine the effect of efforts to tackle obesity and other public health issues through planning and the food environment. Deliveroo’s CEO has already observed changes towards online and apps consumer behaviour brought forward by one to three years (BBC News, 29 June 2020). For policy-makers, it may be helpful to identify the impacts and effects of issues through impact assessments, such as health impact assessments, so they can be accounted for earlier in the process (see Fig. 1 for an impact pathway).

In a more nuanced way, access to the food environment isn’t all about absolute numbers but about exposure to potential less healthy food outlets in areas of higher socio-economic deprivation or around more at-risk populations such as children, and land uses, such as schools. Government guidance (PHE 2020(4)) and local authorities (Keeble et al. 2019) have policies and guidance relating to restriction of fast food outlets. In the medium term, once the temporary changes are lifted, there needs to be a recognition and awareness how relevant existing policies can still be to address a post-COVID retail environment.

Conclusions: opportunities for creativity and agility

The problem of obesity, exposed by existing inequalities, may have been exacerbated during COVID-19 (PHE 2020(2)) with an emerging body of research showing that obesity is a major risk factor in people becoming severely ill or dying from COVID-19 (PHE 2020(3)).

The package of lockdown actions taken during the height of the pandemic by governments will have changed, established and sustained how consumers interact with the food retail environment. There are already underlying trends such as the rise of dark kitchens and dietary inequalities around, affordable food access and food poverty which will have been potentially accelerated by COVID-19. This combination makes it potentially more challenging to tackle the complex issue of obesity through changing spatial land use planning controls in the short term.

COVID-19 is having impacts across the different systems, sectors and interventions, and there is a need to better understand the pros and cons in a delicate balancing act across social and economic drivers. Existing legislative and policy requirements may need to be reconciled with the impact of changes from COVID-19. We hope this commentary provides a useful contribution to ongoing discussions on the systemic impact on the food environment, and how they can be addressed through planning.

References

Bambra, C., R. Riordan, J. Ford, et al. 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-214401.

BBC News. 2020. Coronavirus: Restaurants are 'hurting', says Deliveroo boss. www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-53215411.

Blackshaw, J., M. Ewins, and M. Chang. 2019. Health Matters: addressing the food environment as part of a local whole systems approach to obesity, Public Health England, https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2019/08/08/health-matters-addressing-the-food-environment-as-part-of-a-local-whole-systems-approach-to-obesity/.

Burgoine, T., N.G. Forouhi, S.J. Griffin, N.J. Wareham, and P. Monsivais. 2014. Associations between exposure to takeaway food outlets, takeaway food consumption, and body weight in Cambridgeshire, UK: population based, cross sectional study. BMJ 348: g1464.

Costa-Font, M., and C. Revoredo-Giha. 2020. Covid-19: the underlying issues affecting the UK’s food supply chains, LSE Business Review, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2020/03/25/covid-19-the-underlying-issues-affecting-the-uks-food-supplychains/.

Cummins S., N. Berger, L. Cornelsen, J. Eling, V. Er, and R. Greener et al. 2020. COVID-19: impact on the urban food retail system and dietary inequalities in the UK. Cities & Health.

Green, L., L. Morgan, S. Azam, L. Evans, L. Parry-Williams, and L. Petchey et al. 2020. A health impact assessment of the ‘Staying at Home and Social Distancing Policy’ in Wales in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Executive Summary. Cardiff, Public Health Wales NHS Trust.

Keeble, M., T. Burgoine, M. White, C. Summerbell, S. Cummins, and J. Adams. 2019. How does local government use the planning system to regulate hot food takeaway outlets? A census of current practice in England using document review. Health & Place 57: 171–178.

Newton, J., et al. 2015. Changes in health in England with analysis by English regions and areas of deprivation 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet 386 (10010): 2257–2274.

NICE. 2020. Cardiovascular disease prevention, Public Health Guideline [PH25].

Public Health England. 2020. (1), Beyond the data: Understanding the impact of COVID-19 on BAME groups.

PHE. 2020. (2), Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19.

PHE. 2020. (3), Excess Weight and COVID-19 Insights from new evidence.

PHE. 2020. (4), Using the planning system to promote healthy weight environments.

Rutter, H., N. Savona, K. Glonti, J. Bibby, S. Cummins, D.T. Finegood, et al. 2017. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. The Lancet. 390 (10112): 2602–2604.

Savills. 2020. The initial impact of Covid-19 on the retail and leisure market.

The Food Foundation. 2016. Force-fed. Does the food system constrict healthy choices for typical British families?.

Townshend, T., and A. Lake. 2017. Obesogenic environments: Current evidence of the built and food environments. Perspectives in Public Health 137 (1): 38–44.

UK Parliament, Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) (Amendment) Order 2020.

UN-Habitat and WHO. 2020. Integrating health in urban and territorial planning: A sourcebook for urban leaders, health and planning professionals.

WHO. 2020. Alcohol and Covid-19: What you need to know factsheet.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, M., Green, L. & Cummins, S. All change. Has COVID-19 transformed the way we need to plan for a healthier and more equitable food environment?. Urban Des Int 26, 291–295 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-020-00143-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-020-00143-5