Abstract

Objectives

To measure the effect of arranged marriages on criminal convictions among male ethnic minority youth in Denmark.

Methods

To identify the effect, we rely on administrative data from before and after a national policy reform in 2002 that restricted ethnic minority youths’ access to their most prevalent type of marriage until both spouses were at least 24 years of age. We use difference-in-differences estimation and meticulously analyze potential time trends in the data.

Results

Although the reform substantially decreased marriage rates in both the short (24 percent decrease at age 24) and longer (10 percent at age 30) run, this reform effect produced no response in criminal conviction risks in neither short nor long run.

Conclusion

Criminologists discuss whether social institutions, such as marriage, influence desistance from crime or whether the association is driven by unobserved heterogeneity. Several empirical strategies have been proposed to settle the discussion. Our contribution to this line of research is an alternative empirical strategy that relies on a natural experiment. Our study focuses only on one specific type of marriage in one context and focuses on criminal convictions rather than behavior per se—which are important limitations. Still, results uniformly reject the hypothesis that the marriages in our study influenced criminal convictions.

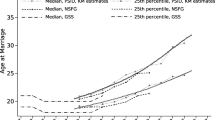

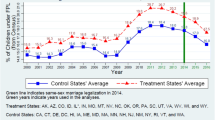

SOURCE: Own calculations based on data from Statistics Denmark

SOURCE: Own calculations based on data from Statistics Denmark

SOURCE: Own calculations based on data from Statistics Denmark

SOURCE: Own calculations based on data from Statistics Denmark

SOURCE: Own calculations based on data from Statistics Denmark

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Self-control is the capability to abandon short-term pleasures that potentially result in long-term negative consequences and is fundamentally established in childhood. Inadequate parenting (insufficient behavioral monitoring; insufficient recognition of bad behavior; and inconsistent punishment of bad behavior) produces a lack of self-control in children, and a person’s level of self-control is then more or less stable across the life course. The relative stability implies that self-control affects most outcomes in life, such as marriage or crime, and it matters for the persistence in maintaining these outcomes.

To the best of our knowledge, only one existing study uses policy reform to analyze marriage effects. This is Frimmel, Halla, and Winter-Ebmer (2014), who exploit the abolishment of a marriage subsidy in Austria to study the effect of divorce on fertility and fertility outcomes. Our study is the first to use policy reform to study the effect of marriage on crime.

The reform also limited access to family reunification for couples older than 24 years of age. After the reform, such applicants were required to present DKK 50,000 [2002 prices] to cover the basic costs of maintaining a reunified spouse, and the applicant in Denmark could not have received any social assistance within the past year. In addition, the reform required that applying couples’ aggregate attachment to Denmark should exceed their attachment to any other country, unless the applicant in Denmark has resided legally in the county for at least 28 years. These limitations to marriages after the reform applied similarly to both the pre and post reform groups and therefore do not matter for the impact of the 24-year age requirement, which we rely on in our analyses (the extra limitations only affects the level of marriages, not the difference between pre and post reform groups).

Note how the percentage of who marries within each month also decreases in mid-2000. This decrease is caused by another reform, which required family reunification applicants to have at least as strong attachment to Denmark as to any other country to be eligible for family reunification in Denmark. However, this reform had a limited impact on marriage rates (as was also seen in Fig. 1), and it cannot rule out selection issues in who applies for family reunification. Therefore, we do not use that reform for causal inference.

Figure A1 in the Online Supplementary Material shows the corresponding figure for young Danes. The figure shows that the reform had no impact on these men’s marriage rates, which is also what we would expect as family reunification is not their predominant type of marriage.

The group does, however, represent a significant and growing percentage of young men in Denmark. Among 24-year-old men, the percentage with ethnic minority backgrounds increased from below two percent in the early 1980s to 7.7 percent in 2002 (our reform year) and up to 14.5 percent in 2020 (own calculations based on data in Table FOLK2 at statistikbanken.dk (Statistics Denmark’s public statistical tool)).

Fox (1975) shows that the degree of homogamy is similar in “love marriages” and in arranged marriages in Ankara, Turkey. And that although arranged marriages tend to be more traditionalist, there is little evidence of differential impact of the two marriage types on behavior; behavioral differences are likely the result of selection into the two types of marriage. Results from comparing the two marriage types within the same city and population in Turkey in the 1970s are hardly informative regarding the comparability of the two marriage types for Danes versus ethnic minority youth in 2002, however.

Our definition of ‘non-western ethnic minority backgrounds’ merges two official definitions from Statistics Denmark (Statistics Denmark 2017). ‘Minorities’ are immigrants and their children. Immigrants moved to Denmark and neither of their parents were born in Denmark and had Danish citizenship. For children, if no information is available on the parent yet the child has foreign citizenship, the child is also counted as a belonging to a minority. ‘Non-western’ refers to countries not on this list: the 27 EU countries, England, Andorra, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Monaco, Norway, San Marino, Switzerland, the Vatican, Canada, the United States of America, Australia, and New Zealand.

Empirical setups that benefit from plausibly exogenously induced variation in treatment propensities would often be analyzed using an instrumental variable (IV) approach. The IV approach is, however, highly sensitive to time trends in the data, which the difference-in-differences estimator is much better designed to handle. In fact, we ran the IV approach on our data and – discomfortingly – were able to “detect” reform effects at points when there was no reform, which emphasizes the IV approach’s vulnerability to time trends. Results from this exercise are available on request from the corresponding author.

For these calculations, we rely on Stata’s nlcom command.

General time trends, such as increasing hostility towards immigrants, would not impact our results, however, as the difference-in-differences model would effectively factor these out.

References

Agnew R (1992) Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology 30(1):47–88

Allendorf K, Ghimire DJ (2013) Determinants of marital quality in an arranged marriage society. Soc Sci Res 42(1):59–70

Andersen LH (2018) “Danish Register Data: Flexible Administrative Data and their Relevance for Studies of Intergenerational Transmission”. In: Eichelsheim VI, Steve GA van de Weijer (eds) Intergenerational continuity of criminal and antisocial behaviour: An international overview of studies, Cambridge, UK: Routledge

Beaver KM, Wright JP, DeLisi M, Vaughn MG (2008) Desistance from delinquency: the marriage effect revisited and extended. Soc Sci Res 37(3):736–752

Bersani BE, Doherty EE (2013) When the ties that bind unwind: examining the enduring and situational processes of change behind the marriage effect. Criminology 51(2):217–474

Bersani BE, Doherty EE (2018) Desistance from offending in the twenty-first century. Ann Rev Criminol 1:311–334

Blokland AAJ, Nieuwbeerta P (2005) The effects of life circumstances on longitudinal trajectories of offending. Criminology 43(4):1203–1240

Bushway SD, Tahamont S (2016) Modeling long-term criminal careers: what happened to the variability? J Res Crime Delinq 53(3):372–391

Cobbina JE, Huebner BM, Berg MT (2012) Men, women, and postrelease offending: an examination of the nature of the link between relational ties and recidivism. Crime Delinq 58(3):331–361

Craig JM, Diamond B, Piquero AR (2014) “Marriage as an Intervention in the Lives of Criminal Offenders.” In: Effective Interventions in the Lives of Criminal Offenders, edited by Humphrey JA, Cordella P, New York City, NY: Springer, pp 19–37

Danish Immigration Service (2002) Nøgletal på udlændingeområdet 2001. Danish Immigration Service, Copenhagen

Dunning T (2012) Natural experiments in the social sciences. A design-based approach, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

Forrest W (2014) Cohabitation, relationship quality, and desistance from crime. J Marriage Fam 76(3):539–559

Fox GL (1975) Love match and arranged marriage in a modernizing nation: mate selection in Ankara, Turkey. J Marriage Fam 37(1):180–193

Frimmel W, Halla M, Winter-Ebmer R (2014) Can pro-marriage policies work? An analysis of marginal marriages. Demography 51(4):1357–1379

Giordano PC, Cernkovich SA, Rudolph JL (2002) Gender, crime, and desistance: toward a theory of cognitive transformation. Am J Sociol 107(4):990–1064

Giordano P, Schroeder RD, Cernkovich SA (2007) Emotions and crime over the life course: a neo-Meadian perspective on criminal continuity and change. Am J Sociol 112(6):1603–1661

Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T (1990) A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA

King RD, Massoglia M, Macmillan R (2007) The context of marriage and crime: gender, the propensity to marry, and offending in early adulthood. Criminology 45(1):33–65

Laub JH, Sampson RJ (2001) Understanding desistance from crime. Crime Justice 28:1–69

Laub JH, Sampson RJ (2003) Shared beginnings, divergent lives: delinquent boys to age 70. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Laub JH, Nagin DS, Sampson RJ (1998) Trajectories of change in criminal offending: good marriages and the desistance process. Am Sociol Rev 63(2):225–238

Laub JH, Rowan ZR, Sampson RJ (2019) “The age-graded Theory of informal social control”. In: Farrington DP, Lila Kazemian, Piquero AR (eds): The Oxford Handbook of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, Oxford University Press, pp 295–322

Lyngstad TH, Skardhamar T (2011) Nordic register data and their untapped potential for criminological knowledge. Crime Justice 40:613–645

Lyngstad TH, Skardhamar T (2013) Changes in criminal offending around the time of marriage. J Res Crime Delinq 50(4):608–615

Massenkoff M, Rose EK (2020) “Family formation and crime.” Unpublished Working Paper: http://maximmassenkoff.com/FamilyFormationAndCrime.pdf

Matthiessen PC (2009) Immigration to Denmark. Rockwool Foundation Research Unit and University Press of Southern Denmark, Odense

McGloin JM, Sullivan CJ, Piquero AR, Blokland A, Nieuwbeerta P (2011) Marriage and offending specialization: expanding the impact of turning points and the process of desistance. Eur J Criminol 8(5):361–376

Nguyen H, Loughran T (2018) On the measurement and identification of turning points in criminology. Ann Rev Criminol 1:335–358

Osgood DW, Lee H (1993) Leasure activities, age, and adult roles across the lifespan. Soc Leis 16(1):181–207

Osgood DW, Wilson JK, O’Malley P, Bachman JG, Johnston LD (1996) Routine activities and individual deviant behavior. Am Sociol Rev 61(4):635–655

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1993) Crime in the making: pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (2005) A life-course view of the development of rime. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 602(1):12–45

Sampson RJ, Laub JH, Wimer C (2006) Does marriage reduce crime? A counterfactual approach to within-indivicual causal effects. Criminology 44(3):465–508

Simons RL, Stewart E, Gordon LC, Conger RD, Elder Jr GH (2002) A test of life-course explanations for stability and change in anti-social behavior from adolescence to young adulthood. Criminology 40(2):401–434

Skardhamar T, Savolainen J, Aase KN, Lyngstad TH (2015) Does marriage reduce crime? Crime Justice 44(1):385–446

Sobotka T (2008) The diverse faces of the second demographic transition in Europe. Demogr Res 19:171–224

Statistics Denmark (2017) Indvandrere i Danmark 2017. Copenhagen, Denmark: Statistics Denmark

van Schellen M, Apel R, Nieuwbeerta P (2012) ‘Because you’re mine, i walk the line’? Marriage, spousal criminality, and criminal offending over the life course. J Quant Criminol 28(4):701–723

Walmsley R (2016) World prison population list. Institute for Criminal Policy Research, London

Warr M (1998) Life-course transitions and desistance from crime. Criminology 36(2):183–216

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mads Meier Jæger, Christopher Wildeman, numerous seminar participants, and the reviewers and editor at Journal of Quantitative Criminology for excellent comments to previous versions of the manuscript. The authors bear full responsibility for any errors. The authors thank the ROCKWOOL Foundation for funding this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andersen, L.H., Andersen, S.H. & Skov, P.E. Restricting Arranged Marriage Opportunities for Danish Minority Youth: Implications for Criminal Convictions. J Quant Criminol 38, 921–947 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-021-09521-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-021-09521-w