Abstract

Customer-perceived service wellbeing (CPSW) refers to a positive response resulting from the experiential, relational, processual, and interactive character of a service or service situation that contributes to individual customer wellbeing and broader societal wellbeing. This paper aims to offer a conceptual model of the relationships between the wellbeing-focused dimensions of a firm’s activities and CPSW. Building on scholarly insights from the marketing logic and transformative service research (TSR) literature, the paper develops a series of research propositions to articulate the relationships in the conceptual framework. On the basis of the literature review, five wellbeing-focused dimensions of a firm’s activities have been identified as antecedents to CPSW and five customer factors have been identified as potential moderators of the relationship between the wellbeing-focused dimensions and CPSW. This paper reveals arguments in the existing literature to promote a deeper understanding of the impact of the firm’s wellbeing-focused activities on CPSW in light of moderating effects of customers’ psychological and behavioral characteristics. The managerial implication resulting from the framework and the propositions presented here is that managers and service providers need to identify and understand both the wellbeing-focused dimensions of their business and the psychological and behavioral characteristics of their customers; in healthcare services, specifically, both are necessary in order to improve CPSW. This paper highlights a new perspective to better understand the mechanisms of transformative service design that firms should pursue to influence CPSW. This paper offers a theoretical framework depicting how CPSW is generated through the effective unification of the roles of businesses and customers in the context of healthcare services and provides researchers with a new outlook for the development of a multidisciplinary societal wellbeing model.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Scholars define “customer-perceived service wellbeing” as a positive consequence of a service situation that contributes to customer wellbeing (Falter & Hadwich, 2020; Sirgy & Lee, 2006). The construct elucidates the efforts made by firms and customers to create wellbeing values in services, and it advances knowledge in both service and wellbeing research. It has been deemed a “new measure” in the literature responding to paradigm shifts redefining service composition (i.e., more service work, less manufacturing work), addressing the firm’s value proposition, and accrediting the role of customers in value creation (Heinonen et al., 2010).

Journal of Service Research Special Issue on Transformative Service Research: A Multidisciplinary Perspective on Service and Well-being (2012) and recent publications in the area of transformative service research (TSR) have underscored the significance of customer service wellbeing in an array of services, including healthcare (Anderson & Ostrom, 2015; Anderson et al., 2013). The main agenda of TSR is to enhance customer service wellbeing through service design and practices. Extending the emphasis, in traditional service research, on service quality and customer satisfaction, TSR emphasizes customer wellbeing as the primary consideration in designing or providing services (e.g., configuring healthcare offerings or service designs to reduce health disparities) (Amorim Lopes & Alves, 2020).

Anticipating the importance services will hold for customers in the future, scholars argue that an economic advantage will accrue to firms that emphasize customer service wellbeing (Anderson & Ostrom, 2015; Blocker & Barrios, 2015). They highlight transformative service design (TSD) — the conceptual and empirical extension of TSR — and its potential contribution to service wellbeing. Transformative service design, which broadly includes service design, service practices, and transformative services (Blocker & Barrios, 2015) has a natural conceptual relation to CPSW. Patrício et al. (2020) note that service design can catalyze healthcare transformation. They offer research directions for leveraging service design towards people-centered, and creative and transformative approach, and underscore TSD approach to develop innovative solutions for healthcare change and wellbeing.

More work is needed to understand the process of creating customer service wellbeing and the unique roles of service design and service entities in improving CPSW (Alves et al., 2016; Amorim Lopes & Alves, 2020). At present, CPSW and its determinants are inadequately understood, and their connection to TSD remains to be established. Refining the conceptualization of CPSW and our knowledge of the factors that influence it is critical to service researchers and marketers alike. This paper aims to conceptualize CPSW and relate it to TSD through such issues as service design, service practices, and transformative services.

Under the wide umbrella of TSR, researchers single out the role of service design, service practices, and transformative services in developing a focus on wellbeing within a firm that has the potential to influence CPSW (Anderson & Ostrom, 2015; Blocker & Barrios, 2015). Scholars praise firms’ efforts to integrate resources in new or transformative ways (Baptista et al., 2021) and argue for the transformative potential of wellbeing value as a staged sustainable business strategies for business and society (Bhattacharya, 2017; Gauthier, 2017).

According to Service-Dominant (SD) logic, firms play an active role in value propositions through service design and practices, where value is co-created through customer–provider interaction (Vargo & Lusch, 2004, 2008). The SD logic is inherently compatible with the positive marketing movement (i.e., wellbeing marketing) (Alves et al., 2016; Sirgy & Lee, 2006) and with social construction theories (with their concepts of social structures, social systems, roles, positions, and interactions) (Edvardsson et al., 2011). The SD logic further expounds how the employee – customer interaction can deliver value to customers, firms, and society at large — including value-in-use (e.g., positive experience, personalization, relationship, engagement) and value-in-social-context (e.g., social construction). These values center on customers’ positive experiences (Sandström et al., 2008) that are akin to customer service wellbeing (Falter & Hadwich, 2020).

The wellbeing-focused factors studied in this paper include firms’ efforts in value co-creation, evidence-based design, service guarantee and complaint handling within the firm, social and ethical responsibility, and support for customers’ religious needs. These factors have been studied separately in customer satisfaction research; however, the question of how service wellbeing emerges for customers through value-generating processes facilitated by firms themselves remains to be addressed. No study has yet investigated these factors as antecedents of CPSW. Hence, the second objective here is to construct theoretical relationships between wellbeing-focused dimensions of a firm’s activities and CPSW.

Challenging the assumption of the customer’s passive role in service transactions or exchange processes, the customer-dominant (CD) logic adopts a more holistic view of how value emerges for the customer (Heinonen et al., 2010). According to CD logic, customers create value through their contexts, activities, practices, and experiences. Arnould and Thompson (2005) further note that service organizations have an interest in exploring customers’ contexts, activities, practices, and experiences. For instance, customer-centered healthcare providers treat patients as customers or active recipients of healthcare services — as partners in value co-creation — by putting customers at the heart of service design and the decision process (Frow et al., 2016; Joiner & Lusch, 2016). Based on these ideas, it can be argued that the CD logic supports the suggestion of a moderating role of customer factors on the link between the wellbeing-focused dimensions of a firm’s activities and CPSW.

To enrich the conceptual framework (Gonzalez-Mulé & Aguinis, 2018), research underscoring customers’ psychological and behavioral factors is necessary. The present study proposes a moderating role for five specific customer factors — the customer’s efforts in value-creation activities, customer-perceived value, customer expectation, customer personal moral philosophies, and customer religiosity — in the relationship between the wellbeing-focused dimensions of a firm’s activities and CPSW. Past research has delineated the effects of customer factors on dependent variables such as behavioral intentions, quality of life, and customer satisfaction (Muhamad & Mizerski, 2007; Sweeney et al., 2015). However, the moderating influence of customer factors in the link between the wellbeing-focused aspects of a firm’s activities and CPSW has yet to be examined. Hence, the third objective is to review the potential moderating role of customer factors on the relationship between the wellbeing-focused aspects of a firm’s activities and CPSW.

To summarize, developments in marketing logic and TSR press for a new, combined knowledge of TSD and customer service wellbeing. In this context, the present paper has three objectives: (1) to revisit the conceptualization of CPSW, considering the status of TSD as an antecedent to CPSW, (2) To propose theoretical propositions of the relationship between five wellbeing-focused aspects of a firm’s activities (the firm’s efforts in value co-creation, evidence-based design, service guarantee and complaint handling within the firm, social and ethical responsibility, and support for customers’ religious needs) and CPSW, and (3) To build theoretical propositions of the moderating roles of the five customer factors (the customer’s efforts in value-creation activities, customer-perceived value, customer expectation, customer personal moral philosophy, and customer religiosity) on the links between the wellbeing-focused dimensions of a firm’s activities and CPSW.

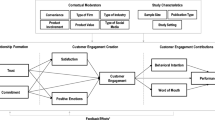

The paper is conceptual and follows a similar approach to the theme-based literature reviews of past studies, where several research propositions are developed to delineate the expected relationships among the selected constructs (e.g., Kalaignanam & Varadarajan, 2012; Karande et al., 2011). The paper has used past empirical findings to support arguments in building propositions. However, the propositions developed in this study states new relationships among constructs of the conceptual framework (see Fig. 1). The authors review research in the fields of service quality, healthcare service quality, and transformative service design as well as studies of wellbeing-focused dimensions within firms, customer factors, and customer service wellbeing. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The study first defines CPSW and discusses how TSD connects TSR and marketing logics. It then presents the theoretical framework and summarizes the various constructs of the model in Table 1 (Appendix). The paper next develops a series of research propositions regarding main effects and moderating effects. It then discusses the implications of the model for theory and practice. Finally, the authors conclude by proposing an agenda for future research.

2 Literature review and development of propositions

Customer-perceived service wellbeing combines concepts of wellbeing, consumer wellbeing, and customer service wellbeing. In seeking new ways to explain customer service wellbeing, the authors unite three service-related concepts — service design, service practices, and transformative services — that fall under the umbrella of TSD. The authors draw on multiple streams of literature to describe these aspects and their relationship with CPSW. The following discussion provides a theoretical backdrop against which to build a conceptual framework encompassing the wellbeing-focused aspects of a firm’s activities, CPSW, and customer factors.

2.1 Customer-perceived service wellbeing (CPSW)

Wellbeing includes quality of life, life satisfaction, and a general sense of happiness (Deci & Ryan, 2008). In marketing and service science, “customer service wellbeing” (or “consumer wellbeing”) refers to wellbeing that emerges from different service situations and service consumption processes (Sirgy & Lee, 2006). It describes a state in which consumers’ experiences with goods and services — experiences related to the acquisition, preparation, consumption, ownership, maintenance, and disposal of specific categories of goods and services in the context of their local environment — are judged to be beneficial to both consumers and society at large (Sirgy & Lee, 2006). More recently, Falter and Hadwich (2020, p.6) have defined customer service wellbeing by noting that “a positive response can be affective and cognitive and varies in intensity of positive emotions during the service process, engagement during the service process, positive relationship with service employees, service meaning, and service accomplishment,” further adding that customer service wellbeing includes both cognitive and affective aspects, is much stronger than customer satisfaction and service quality, and emerges from the service interaction and customer involvement.

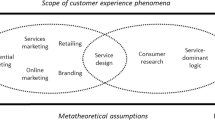

In advancing TSR, Anderson et al. (2013) provide a comprehensive view of how the interaction between service entities (e.g., employees, service processes or offerings, organizations) and consumer entities (e.g., individuals, collectives such as families or communities, the ecosystem) influences wellbeing outcomes for both. Although SD logic and TSR both highlight service interaction (Kuppelwieser & Finsterwalder, 2016), TSR, additionally, looks for socially and culturally desirable practices within service settings, where firms make deliberate attempts to enhance the wellbeing of vulnerable or marginalized consumers with diverse backgrounds, religious orientations, and so forth (Ostrom et al., 2015). The concept of CPSW can be refined by drawing on the field of TSR, which emphasizes service interaction and social dimensions, and SD logic, which focuses on value co-creation. When these perspectives are taken into account, we arrive at a definition of CPSW as a positive response resulting from the experiential, relational, processual, and interactive character of a service or service situation that contributes to individual customer wellbeing and broader societal wellbeing (adapted from Falter & Hadwich, 2020).

2.2 Transformative service design (TSD)

Transformative service design is an integrated concept that explains the firm’s value-generating process, including service design, service practices, and transformative services (Blocker & Barrios, 2015). Traditional service design is based on the goods-dominant concept, which assumes that value is embedded in the product/service. The components of service design are people, processes, and physical evidence (Flynn et al., 1995). Studies in this area focus on satisfying customers through reducing variation in service delivery and offering key service attributes (Bitner, 1992; Parasuraman et al., 1988). As in the sale-orientation perspective, customers play a role in service transactions and realize value at the point of sale (i.e., value-in-exchange). However, later, scholars have described service design as a consumer-centric activity and a continuous process of improving design elements that are likely to influence sales, satisfaction, and societal wellbeing (Amorim Lopes & Alves, 2020; Anderson et al., 2013).

Since service design is seen as static, whereas the nature of service is processual and relational, scholars have introduced the concept of service practices, which is a personalized, iterative, evolving concept relating to service interaction (Anderson et al., 2018). Value-in-use and value-in-context have been targeted through service practices with a particular goal during employee–customer interaction (Sangiorgi, 2011). The SD logic advances the concept of service practices and emphasizes the firm’s active role in service interaction (Vargo & Lusch, 2004). Hence, service practices reflect a firm’s purposeful service interaction (e.g., value facilitations from service provider) (de Jesus & Alves, 2019) and value co-creation practices (Grönroos, 2011). In healthcare, for instance, to improve CPSW, there is a need for service providers to facilitate overall value creation process by adding positive experiential value (Joiner & Lusch, 2016; Wells et al., 2015). In the context of public healthcare services, Amorim Lopes and Alves (2020) show that the process of coproduction/creation relates with enables, such as interactive and dynamic relationships between public care service providers and customers.

With the emergence of TSR, researchers have broadened the perspective of service design and practices to include the transformative potential of services into the firm’s service programs (Anderson & Ostrom, 2015). The aim is to generate transformative value, which reflects the contributions of both the firm and the customer to improving service wellbeing (Blocker & Barrios, 2015). These contributions are strongly tied to the firm’s service offerings (for instance, socially and culturally desirable medical practices) and facilitation of value (for instance, allowing customer engagement or co-design of services) (Amorim Lopes & Alves, 2020; Sangiorgi, 2011; Wells et al., 2015).

Transformative services that address how firms can reduce consumer stress through handling customer complaints and supporting customers’ religious needs are of interests to scholars and marketers (Friele et al., 2008; Muhamad & Mizerski, 2007). In the hospital context, there is evidence to suggest that transformative services can help healthcare providers manage diversity and cultural complexity through social and ethical responsibility, service guarantees and complaint handling processes, and support for customers’ religious needs. These wellbeing-focused activities contribute to positive experiences for consumers, quality of life that qualify as customer service wellbeing (Amorim Lopes & Alves, 2020; Falter & Hadwich, 2020).

Going forward, the role of specific customer psychological and behavioral factors in constructing the transformative value of service experiences are considered as an apparatus of comprehensive societal transformation (Blocker & Barrios, 2015). Past studies highlight the role of customer factors and the nature of their contribution to CPSW (Friele & Sluijs, 2006; Sweeney et al., 2015), focusing on inspiring changes that arise within the market and go beyond customer reactions within the purchase cycle (Blocker & Barrios, 2015). Heinonen et al. (2010) argue for placing the customer, rather than the service, service provider, or service system, at the center and underscore the role of the customer’s characteristics, context, and personal life. Accordingly, more emphasis on customer characteristics could contribute to understanding the transformational effect of the independent variables on the dependent variable. Customer factors may function as an intervening construct in relations between firms and customers. Such a view resonates well with the moderating role of customer factors in consumption of products and services as put forwarded by Prebensen et al. (2016) and Troye and Supphellen (2012). This model promises to accommodate the significant changes in the way services are designed and delivered in healthcare due to the rise of a patient-centered approach (Vogus & McClelland, 2016).

2.3 A conceptual model of CPSW

This study emphasizes the incorporation of the wellbeing-focused aspects of a firm’s activities and particular customer psychological and behavioral factors in order to develop a transformative service model for CPSW. The conceptual framework presented in Figure 1 identifies both firms and customers as resource integrators acting in a service setting, integrating five wellbeing-focused dimensions (the firm’s efforts in value co-creation, evidence-based design, service guarantee and complaint handling within the firm, social and ethical responsibility, and support for customers’ religious needs) with five customer factors (the customer’s efforts in value-creation activities, customer-perceived value, customer expectation, customer personal moral philosophies, and customer religiosity). The definitions and operational measures of each construct in the framework can be found in Table 1 (Appendix). The following section offers propositions regarding the theoretical relationships between the main effects and the moderation effects specified in the conceptual framework (Figure 1).

2.4 Theoretical propositions on the main effects

Firm’s efforts in value co-creation (Firm EVCC)

During the customer – employee interaction, a firm can participate with the customer as a co-creator of value (Vargo & Lusch, 2008). The firm needs to put effort into purposeful, strategic interaction with the customer either to facilitate customer value creation or to become a value co-creator (Grönroos, 2011). The firm makes these efforts through an open system and collaborative environments that are likely to improve the total customer service experience. Sandström et al. (2008) decode functional and emotional values from customer service experiences that, taken together, contribute to customer service wellbeing. Research on value co-creation shows that dimensions related to firm EVCC affect customer-perceived quality, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty (Albinsson et al., 2016). For instance, Parahoo and Al-Nakeeb (2019) provided empirical evidence for the role of service ecosystem in leading to social innovation and wellbeing creation in the public sector, underscoring technological factors that facilitate/enable interactions between the institution and its citizens and (b) its partners.

Hospitals’ efforts in value co-creation facilitate patients’ active involvement in the physician – patient interaction. Promoting patient involvement creates value and accessibility, improving healthcare outcomes (including increased medication adherence, reduced medical negligence, and healthcare satisfaction) (Raposo et al., 2009; Seiders et al., 2015). Research indicates that customer-centered practice helps professionals (including doctors, nurses, and staff) understand customers’ needs (Seiders et al., 2015). Albinsson et al. (2016) have demonstrated that a firm’s readiness to support strategic value co-creation impacts on service loyalty. Likewise, the patient-centered approach promotes the concept of supporting patients in their efforts at value creation (Vogus & McClelland, 2016). Russo et al. (2019) further show that allowing patients to be partners or co-producers enhances their value-creation behaviors and thus CPSW. Hence, the following proposition is offered.

-

P1: The firm’s efforts in value co-creation will have a positive influence on customer-perceived service wellbeing.

Evidence-based design (EBD)

Evidence-based design in healthcare is a holistic view of healthcare service design that ensures safety and security, promotes the recovery and healing process, creates a friendly environment for staff, physicians, patients, and families, and substantially affects service wellbeing. This holistic service design creates the potential for better medical outputs (including patients’ healing, satisfaction, and revisit intentions) (Hamed et al., 2017). From the service provider perspective, scholars have examined the impact of EBD on doctors, nurses, and medical staff. Healthcare professionals working with better physical conditions (for instance) feel more satisfied with their jobs and perceive higher wellbeing (Campos-Andrade et al., 2013). Evidence-based design has a significant influence on nurses’ perceptions of service climate (Steinke, 2015). It reduces the employee stress and contributes to efficient and effective delivery of services (Henriksen et al., 2007; Ulrich et al., 2010). Overall, research on EBD reveals the beneficial impact of evidence-based healthcare service design on service providers and customers (for review, Salonen et al., 2013). Therefore, the authors argue that EBD will have an impact on CPSW.

-

P2: Evidence-based design will have a positive influence on customer-perceived service wellbeing.

Service guarantees and complaint handling procedures

These practices of high-performance businesses involve promises to deliver a certain level of service quality. Such promises strengthen a hospital’s culture of service excellence and shape a responsibility to provide patients with positive service experiences and build trust-based relationships (Berry, 2019). Firms with such practices prepare their employees to deliver excellent service and recognize customer dissatisfaction (Hogreve & Gremler, 2009). The literature evidences the effect of these practices on the internal phenomena of employee motivation and service quality (Hays & Hill, 2006) as well as on healthcare customer perception and satisfaction (Kennett-hensel et al., 2012). The handling of patient complaints also influences CPSW (Friele & Sluijs, 2006). Beyond these general consequences, service guarantees and complaint handling procedures lead to psychological comfort, emotional attachment, recovery from negative emotions, and improved customer service wellbeing — all dimensions of CPSW (Falter & Hadwich, 2020). Based on this context, the following proposition is offered:

-

P3: Service guarantees and complaint handling procedures will have a positive influence on customer-perceived service wellbeing.

Social and ethical responsibility

Moral philosophies often articulate a relationship between social and ethical responsibility and a sense of wellbeing (Forsyth, 1992; Vitell et al., 1993). Consumers use moral criteria to identify contributions to wellbeing from firms that participate in social causes such as blood donation programs, supporting flood victims, and promoting environmental awareness. For instance, Sureshchandar et al. (2002) note that customers perceive high service quality when firms support social causes. Bhattacharya (2017) reveal that voluntary and strategic corporate social responsibility initiatives generate the most sustainable mutual benefit to the firm itself and its social beneficiaries. Firm’s cause-related campaign and/or social responsibility positively affects consumers’ attitudes toward the firm (Bianchi et al., 2020; Waris & Hameed, 2020), and it also encourages employees to be regular, punctual, sincere, ethical, honest, and dutiful and not to strike (Sureshchandar et al., 2002). This factor can be a vital indicator of a focus on wellbeing in the healthcare context. Duggirala et al. (2008) for example, find a significant relationship between patient satisfaction and social responsibility. Thus, the authors propose the following:

-

P4: Social and ethical responsibility will have a positive influence on customer-perceived service wellbeing.

Support for customers’ religious needs

Offering support for customers’ religious and spiritual needs generates scope for value creation because it expresses broader cultural and societal values. Fam et al. (2004) note that many of the values held by individuals and societies originate from religion. Religion influences people’s daily activities and decisions (Delener, 1994). Moreover, religious people are characterized as being more logical and more able to cope with mental dissonance. In the healthcare context, patients often experience stress, and stress is known to be related to wellbeing. Bonelli et al. (2012) have identified religious beliefs and practices as helpful in coping with a stressful life. Eid and El-Gohary (2015) show the significant effects of service attributes facilitating religious tasks on customer satisfaction. Notably, hospitals’ support for customers’ religious needs is a significant predictor of customer-perceived service quality (Tomes & Chee Peng Ng, 1995) and patient-reported outcomes (Moons et al., 2019). Additionally, patients express the highest level of satisfaction when service providers discuss religious concerns (Williams et al., 2011). This evidence suggests healthcare providers should support customers’ religious needs in a service setting. Hence, the authors offer the following proposition:

-

P5: The firm’s support for customers’ religious needs will have a positive influence on customer-perceived service wellbeing.

2.5 Theoretical propositions on the moderating effects

This section predicts the moderating roles of particular psychological and behavioral characteristics of customers on the main effect propositions developed in the previous section. For clarity, the authors discuss moderating constructs as though they are categorical variables. However, neither the conceptual arguments relating to the propositions nor their future empirical examination is confined to a categorical scale.

Customer EVCA

Customer’s efforts in value creation activities (customer EVCA) refers to the customer’s efforts in a range of activities through which they may create value either independently or as a co-producer with the service provider (Sweeney et al., 2015). The customer plays an active role in the value-creating process through participative behavior (e.g., information seeking and sharing, responsible behavior, personal interaction) and citizenship behavior (e.g., feedback, advocacy, helping, tolerance) (Yi & Gong, 2013). Bennett (2013) explores that high engagement in terms of a donor’s enthusiasm when supporting an organization, passion for the charity, and deep interest in its activities leads to increased donations, and improved word of mouth. Customers can be classified as high or low in EVCA. In healthcare, a high customer EVCA reflects motivation, learning orientation, diligence in performing recommended activities, and ability to cope with stress (Sweeney et al., 2015), whereas a low customer EVCA indicates that little effort is put into engagement behavior that may create value.

The authors reason that customer EVCA could be an important moderator as customers go through the process of knowledge, persuasion, decision, and confirmation during service experience. Research shows that customers’ health knowledge moderates the association between evaluation of service quality and level of satisfaction (McColl et al., 1996). It also stands to reason that if a customer exercises self-learning behavior towards value creation in healthcare (e.g., being health-conscious, connecting with a physician), customer evaluation of the firm’s wellbeing-focused aspects will be affected.

Troye and Supphellen (2012, p. 33) demonstrate that active consumer engagement in a value-creation process (for instance, preparing a meal) positively biases the evaluation of the outcome (for example, a dish) and the input product (for example, a dinner kit). Another study similarly reveals that the level of customer value-creation activity moderates the relationship between customer experience and customer satisfaction (Prebensen et al., 2016). By the same logic, engagement from the customer with the service interaction makes their service consumption less stressful and more assured. In this respect, if a patient creates value actively (with the service provider), then his or her positive evaluation of wellbeing-focused aspects of services is likely to be amplified, spilling over to CPSW.

Customers with high EVCA are by definition more knowledgeable, more participative, and more independent than those with low EVCA. The firm’s efforts in value co-creation and customer EVCA join together in the value-generating process, meaning that the effect of firm EVCC on CPSW varies depending on the magnitude of customer EVCA. Similarly, the effects of a firm’s service guarantee and complaint handling procedure on CPSW vary with customer EVCA. For instance, customers with high EVCA provide feedback, help other customers, and remain tolerant in stressful or difficult situations. Conversely, customers with low EVCA are prone to breakdown in service failure situations and reluctant to provide constructive feedback, making it difficult to manage the service guarantee and complaint handling process. Therefore, the relationship between these wellbeing-focused aspects and CPSW will be more significant for customers with high EVCA than for those with low EVCA.

-

P1a: The positive relationship between firm EVCC and CPSW is stronger for customers with high EVCA than for customers with low EVCA.

-

P3a: The positive relationship between service guarantee and complaint handling within a firm and CPSW is stronger for customers with high EVCA than for customers with low EVCA.

Customer-perceived value of EBD

Customer-perceived value of EBD refers to the extent to which customers perceive EBD as beneficial (Van Rompay & Tanja-Dijkstra, 2010). In healthcare contexts, the attributes of EBD are evaluated as valuable and useful (Salonen et al., 2013; Ulrich et al., 2008). However, the effects of these attributes vary with contextual factors (e.g., the type of environment) and customer needs (e.g., the degree to which consumers value social contact or stimulation in a specific setting) (Van Rompay & Tanja-Dijkstra, 2010). Hence, customer’s perception of value helps increase the customer-perceived benefits (Jiménez-Castillo et al., 2013) and wellbeing associated with the EBD. The value of EBD depends on the customer’s need or desire in the service setting (Salonen et al., 2013). Customers with high perceived value for EBD are likely to perceive EBD as a substantial promoter of their wellbeing and to recognize that the firm will offer better support services, resulting in greater CPSW. In contrast, customers with low perceived value of EBD are typically less oriented toward the environment and have less desire to promote their wellbeing through the firm’s EBD. Thus, the effect of EBD on CPSW is likely to be dampened for these customers. In light of these arguments, the authors offer the following proposition:

-

P2b: The positive relationship between EBD and CPSW is stronger for customers with a high perceived value of EBD than for customers with low perceived value of EBD.

Customer expectation

Firms provide customers with information about their services through word of mouth, publicity, advertisement, explicit and implicit promises, and communication media (Zeithaml et al., 1993). Additionally, customers acquire information from other sources, including as their own experience, expert opinions, and so on. Hence, prior information and beliefs, either realistic or idealistic, inform customer expectations (Thompson & Suñol, 1995), which may be low or high. Since service guarantees and complaint handling policies indicate a high standard of service performance (Berry, 2019), they raise customer expectations. The existing literature explains that customer expectation is based on the customer’s psychological state (e.g., zone of tolerance, level of involvement) during the service purchase and consumption process (Thompson & Suñol, 1995; Zeithaml et al., 1993). This expectation can be expected to moderate the effect of service guarantees and complaint handling procedures on CPSW, since high expectations and favorable consequences lead to higher satisfaction (Linder-Pelz, 1982).

Zeithaml et al. (1993) argue that explicit or implicit service promises elevate the level of expectation while narrowing the zone of tolerance. Customers with high expectations tend to be delighted when the service performance matches the desired service level. In contrast, the zone of tolerance of customers with lower expectations is large; thus the positive effects of service promises (i.e., service guarantees and complaint handling procedures) on CPSW will be lower for customers with lower expectations than for those whose expectations are higher. Wong and Dioko (2013) find significant moderating effects of customer expectations on the relationships between perceived performance and perceived value and between perceived performance and customer satisfaction: the effect is stronger for customers with high expectations. Based on these arguments and results, the following proposition is offered:

-

P3c: The positive relationship between service guarantees and complaint handling procedures and CPSW is stronger for customers with high expectations than for customers with low expectations.

Customer personal moral philosophy

A customer’s personal moral philosophy influences his or her moral judgments of particular business practices and decisions to participate in those practices (Forsyth, 1992). This category can be expected to affect the customer’s evaluation of a firm’s social and ethical responsibility. Two types of customer perspectives on social and ethical responsibility are idealism and relativism (Vitell & Paolillo, 2004). Customers with high levels of idealism perceive that social and ethical practices result in positive consequences (Forsyth, 1980). In contrast, customers with highly relativist principles tend to avoid the idea of universal moral standards (Forsyth, 1980). The literature reveals that customers with idealistic outlooks seek to avoid harm to society and express concern for the welfare of others (Forsyth, 1992; Vitell et al., 2010) and tend to choose services that make them feel morally correct and socially responsible (Sureshchandar et al., 2002). In contrast, relativist customers live with skepticism and do not tend to consider moral rules and ethical judgments (Vitell et al., 2010). Idealistic customers tend to value social and ethical responsibility more highly than their relativist counterparts (Singhapakdi et al., 1995).

Idealistic people are likely to perceive a firm’s support for customers’ religious needs to be important to CPSW and overall success. Vitell et al. (2010) find that ethical idealism correlates to the perception of the importance of ethics and social responsibility to the success of the firm. Idealistic individuals have higher perceptions of moral intensity (e.g., putting effort into social and ethical responsibility, adherence to religious constraints) than relativistic individuals (Singhapakdi et al., 1999). When idealistic customers recognize the benefits of a firm’s social and ethical responsibility and support for customer religious needs, the positive effects of these wellbeing-focused dimensions on CPSW are enhanced. In this context, the authors present the following propositions:

-

P4d: The positive relationship between social and ethical responsibility and CPSW is stronger for idealistic customers than for relativistic customers.

-

P5d: The positive relationship between a firm’s support for customers’ religious needs and CPSW is stronger for idealistic customers than for relativistic customers.

Customer religiosity

Religiosity involves affiliation with or adherence to a religion and religious knowledge (Muhamad & Mizerski, 2010). Customers with higher religiosity believe in the teachings of a particular religion, possess religious knowledge, and attend and participate in religious activities. These elements shape their behavior in the marketplace and societal practices at large (Delener, 1994; Fam et al., 2004; Muhamad & Mizerski, 2007). As customer religiosity increases, firms’ support for customers’ religious can be expected to build CPSW. When customers with higher religiosity perceive firms’ support for their religious and spiritual needs as valuable, they perceive higher service wellbeing. In contrast, customers with lower religiosity have fewer requirements for religious support and less desire for religious involvement; therefore they do not perceive higher service wellbeing with the firm’s support for their religious needs. This is consistent with prior research (Eid & El-Gohary, 2015) in which religiosity has been shown to moderate the effects of the value of physical attributes on Muslim customer satisfaction. Rey-Moreno et al. (2018) show that religious beliefs moderate the citizen’s level of preference for the different channels to access public services (face-to-face, mail, phone and Internet).

Similarly, people with higher religiosity are more empathetic and concerned for the welfare of others; they tend to be more conservative and more idealistic than their less religious counterparts (Singhapakdi et al., 1999). Singhapakdi et al. (1999) also report that idealistic customers tend to perceive social and ethical responsibility as more important than their relativist counterparts. Thus, the highly religious customer is more interested in the social and ethical responsibility of service providers than the less religious one.

Customers with higher religiosity also hold stronger views on firms’ support for customers’ religious needs (Bloomer & Al-Mutair, 2013; Padela & Curlin, 2013). Hopkins et al. (2014) hypothesize that the highly religious customer perceives greater social responsibility of the sponsor than does the less religious group. If these moderation effects are verifiable, then the importance of considering supports for customers’ religious needs in healthcare institutions, especially in the context of service encounters and managing stressful events, will be evident. Thus, the authors propose the following:

-

P4e: The positive relationship between social and ethical responsibility and CPSW is stronger for customers with higher religiosity than for customers with lower religiosity.

-

P5e: The positive relationship between a firm’s support for customers’ religious needs and CPSW is stronger for customers with higher religiosity than for customers with lower religiosity.

3 Conclusion

This study develops a new framework by drawing on insights from the literature on TSR, marketing logics, and healthcare services. It proposes that CPSW is the result of a firm’s active involvement in the value-generating process and that particular customer psychological and behavioral factors have a moderating role on the relationship between a firm’s wellbeing-focused activities and CPSW. The authors pursue an interdisciplinary approach to propose a theoretical framework for sustaining a wellbeing advantage in the healthcare context. In line with Russell-Bennett et al. (2019) proposals, this study propels both TSR and social marketing forward: adopting more customer-oriented approaches; and taking a non-linear approach to theory development that innovates and co-creates solutions. By attending to the research agenda forwarded within TSR and applying SD and CD logics, this paper initiates academic discussion of the connection of CPSW with TSD, suggests implications for marketers, and proposes avenues for future research.

3.1 Implications for theory

The first theoretical contribution of this work is the revised conceptualization of CPSW to include a link between TSD and customer’s wellbeing outcomes. Previous studies on TSD contribute significantly to understanding of service design (Parasuraman et al., 1988), service practices (Vargo & Lusch, 2008), and transformative services (Anderson & Ostrom, 2015; Blocker & Barrios, 2015). The present authors argue that the research on TSD and that on CPSW draw on complementary conceptualizations and study similar phenomena. The concept of TSD integrates three service perspectives — service design, service practices, and transformative services — to influence CPSW. The present study focuses on the wellbeing outcomes of these perspectives, as do many studies in marketing and psychology. We suggest that these service perspectives of TSD should be considered in theorizing the wellbeing-focused dimensions of a firm’s activities.

The second theoretical contribution arises from the propositions regarding the effects of the five identified wellbeing-focused aspects of a firm’s activities on CPSW. The insights of these propositions advance Barry's (2020) case on the critical reflection on the enablers of transformative health promotion action. While the existing literature relates these aspects to customer satisfaction and focuses on services such as shopping, restaurants, finance, travel, music, and theaters, the present authors consider how these aspects impact CPSW in healthcare, synthesizing multiple streams of literature to underline the firm’s active role in enabling the generation of value (Grönroos, 2011). The study thus contributes to the literature that advocates for creating and maintaining a sustainable service environment (Hamed et al., 2017; Ulrich et al., 2008), a positive service experience (Berry, 2019), and positive emotions relating to social, ethical, cultural, religious, and community issues (Bonelli et al., 2012).

There is consensus among theorists that customers differ in their orientations and perceptions based on their social, cultural, religious, personal, and demographic characteristics. Hence, the third theoretical contribution concerns the role of specific customer factors on service experiences in healthcare. The paper explores how the customer’s psychological and behavioral characteristics might strengthen the effect of the wellbeing-focused aspects of a firm’s activities on CPSW and thereby contributes to the knowledge of marketing logics (Heinonen et al., 2010). The authors find arguments in the existing literature to promote a deeper understanding of the impact of the firm’s wellbeing-focused activities in light of customer characteristics, advancing the social support concept in relation to consumer research, segmentation and targeting, and marketing mix in future social marketing interventions (Baptista et al., 2020b). These propositions are new to the service wellbeing literature and build on interdisciplinary work on customer value creation activities. Thus, this paper attends the calls for future research on understanding – for example, what persuades customers towards value co-creation and how customers interact within service context and with other members of the society to create value – in order for service providers to understand what strategies are better to support consumers' value-creation processes and to achieve customers' loyalty (Alves et al., 2016).

Alves (2013) and Baptista et al. (2020a) note that the discussion of the co-creation of value, within the SD logic, in the public and nonprofit sector is still limited in scope. Hence, the final contribution is the transformative framework depicting how CPSW is generated through the effective unification of the roles of firms and customers in the context of healthcare services. The framework incorporating wellbeing-focused dimensions of a firm’s services as determinants of CPSW underscores the SD logic, and considering customer’s behavioral and psychological characteristics as boundary conditions extends the CD logic as well as social-psychological theory. The various constructs in this framework have not before been integrated to demonstrate the transformative potential service framework that generates CPSW. The theoretical framework addresses the central question of how firms can support societal practices, customers’ activities, service experiences, and psychological constructions and advances the current discussion on transformative service design, and value co-creation.

3.2 Managerial and societal implications

The first managerial implication is that firms need to upgrade their focus from the traditional view on customer satisfaction and service loyalty to an emphasis on customer service wellbeing. This new perspective means understanding the mechanisms of TSD that firms should pursue to influence CPSW. Another managerial implication resulting from the framework and the propositions presented here is that firms need to identify and understand both the wellbeing-focused dimensions of their business and the psychological and behavioral characteristics of their customers; in healthcare services, specifically, both are necessary in order to improve CPSW.

Baptista et al. (2021) for instance, suggest the use of online healthcare communities for groups of participants that are subject to treatment uncertainty in order for public health, private and not-for-profit health promotion institutions and managers to devise community-based social marketing involvement to improve the quality and increase the volume of social support. Berry (2019) cites the example of service guarantee applies to patients’ dissatisfaction with the service of Pennsylvania-based Geisinger Health System, and underscores the potential strategy of formally guaranteeing a high-quality patient experience, leading to strengthening an organization's culture of service excellence and elevating individual and team accountability to perform the service well and create trust-based relationships with patients. As one of the India’s largest multispecialty hospital chains, Narayana Health (NH) pursues a transformative potential framework to provide high-quality affordable cardiac care to everyone regardless of their ability to pay (www.narayanahealth.org). NH hospital management maintains databases of potential donors or fundraisers and helps patients to communicate with potential donors for possible fund collection. NH follows the production line approach to surgery, and leverages the economies of scale through reengineering service design, materials, use of medical equipment to reduce the cost (e.g. Joint Commission International or JCI-approved process of sterilization of the medical tools to reuse), and offering services through telemedicine networks and Mobile outreach vans.

In line with this, this paper provides opportunities for those businesses that are willing to enhance individual customer and broader societal wellbeing value through more transparent and socially responsible practices. A holistic understanding of customer-related factors allows firms to embed service in the context of society, to segment and target customers and to construct messages for societal marketing programs that will appeal to them (Baptista et al., 2020b). Similar to the findings of Xie et al. (2020), the moderating propositions of customer’s factors imply that firms should consider customer psychological and behavioral factors and encourage customer participation to enhance their service experience and well-being. Finally, healthcare providers need to engage with TSD and consider wellbeing-focused dimensions as new indicators of welfare in order to assist policymakers in designing culturally competent, socially acceptable, and sustainable healthcare practices.

3.3 Future research agenda

The study argues for the adoption of TSD in order to improve CPSW. Although the application to healthcare services is emphasized here, the authors believe that the propositions and the framework apply to many service settings, from financial institutions to restaurants. Empirical research is needed to clarify and test the framework.

It is vital to investigate the influence of moderators to identify their role in the model and the merits of the antecedent and consequent variables. Understanding the role of moderators is critical for insight into the purported relationship and its boundaries (Gonzalez-Mulé & Aguinis, 2018). Apart from the moderating influence, proposed here, of customer characteristics, there are other possible moderating effects. For instance, religiosity plays a significant role in the relationship between service recovery and recovery satisfaction (Rashid & Ahmad, 2014) and firm’s religiosity influences on corporate social responsibility practices (Zaman et al., 2018). The authors suggest focusing on the direct relationship between customer characteristics and other dependent variables — for example, between customer efforts in value-creation activities and behavioral intentions and quality of life (Sweeney et al., 2015) and between customer religiosity and behavioral patterns in the marketplace (Muhamad & Mizerski, 2007).

Although a conceptual foundation can be found in this paper for the relationship between wellbeing-focused aspects within the firm and wellbeing outcomes such as quality of life and life satisfaction, the explicit inclusion of these outcomes in future would result in a more comprehensive framework. In a similar vein, customer satisfaction with healthcare services can, by its nature, be considered “customer service wellbeing” because healthcare directly affects quality of life (Berry & Bendapudi, 2007). Hospital satisfaction influences life satisfaction via personal community healthcare satisfaction and personal healthcare satisfaction (Sirgy et al., 1994). In support of this agenda, Falter and Hadwich (2020) evidence that customer service wellbeing (in healthcare as elsewhere) affects customers’ behavioral intentions and life satisfaction.

This study represents an effort to enhance consumer, employee, community, societal, and global wellbeing through service functions or design elements. Future research on wellbeing-focused factors in other industries and other customer aspects should be considered to extend the theoretical, empirical, and conceptual reach of the framework. Examples of such factors can be derived from several scholarly works (Anderson & Ostrom, 2015; Anderson et al., 2013) and include transformative service networks, transformative technology, transforming lives through charity participation (e.g., services for homeless, ethnic minority groups, childhood healthcare), and workplace wellness programs (Islam et al., 2020; Tremblay, 2020). These factors including ethical qualities of forgiveness and generosity could be a course for future research as they help businesses to become more socially responsible. The role of other customer characteristics, including demographics (e.g., age, gender, income), consumer clusters (e.g., who engage in promoting or boycotting), cultural and societal differences, and psychological aspects (e.g., education, consumer expertise, social support), could also be a subject for future research (Baptista et al., 2020b; Baptista & Rodrigues, 2018). More research is needed to understand the scope of the effects of the collaboration of firms and customers in the context of other entities or actors. For instance, Feng et al. (2019) evidence that interactions with employees, peers and outsiders appeared as necessary conditions to achieve social well-being.

To conclude, combining insights from the marketing logic and transformative service research literature, the present work offers a revised understanding of the wellbeing-focused aspects of a firm’s activity as they relate to customers’ psychological and behavioral characteristics. The combined lens of TSR and marketing logics on CPSW offers a sustainable and integrated view of addressing a more challenging context, i.e., COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing compels firms to redesign service platform and find ways to ensure positive service experience (Barnes et al., 2020). This crisis context has underlined the truth that drivers of customer satisfaction in a “traditional” context are not the same in a crisis context (Barnes et al., 2020; Prentice et al., 2021). The aspects of firms and customers factors reviewed and discussed in this paper are those associated with TSD. By coordinating between TSD and CPSW, this work provides healthcare services with new perspectives on the role of the service provider in service design and the service process and in their customers’ lives. In the authors’ view, the framework is conducive to increasing social, existential, and psychological wellbeing for service providers and customers.

References

Albinsson, P. A., Perera, B. Y., & Sautter, P. T. (2016). DART scale development: Diagnosing a firms readiness for strategic value co-creation. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 24(1), 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2016.1089763

Alves, H. (2013). Co-creation and innovation in public services. Service Industries Journal, 33(7–8), 671–682. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2013.740468

Alves, H., Fernandes, C., & Raposo, M. (2016). Value co-creation: Concept and contexts of application and study. Journal of Business Research, 69(5), 1626–1633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.029

Amorim Lopes, T. S., & Alves, H. (2020). Coproduction and cocreation in public care services: A systematic review. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 33(5), 561–578. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-10-2019-0259

Anderson, L., & Ostrom, A. L. (2015). Transformative service research: Advancing our knowledge about service and well-being. Journal of Service Research, 18(3), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670515591316

Anderson, L., Ostrom, A. L., Corus, C., Fisk, R. P., Gallan, A. S., Giraldo, M., …, Williams, J. D. (2013). Transformative service research: An agenda for the future. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1203–1210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.013

Anderson, S., Nasr, L., & Rayburn, S. W. (2018). Transformative service research and service design: Synergistic effects in healthcare. Service Industries Journal, 38(1–2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2017.1404579

Arnould, E. J., & Thompson, C. J. (2005). Consumer Culture Theory (CCT): Twenty years of research. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 868–882. https://doi.org/10.1086/426626

Baptista, N., Alves, H., & Matos, N. (2020a). Public sector organizations and cocreation with citizens: A literature review on benefits, drivers, and barriers. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 32(3), 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2019.1589623

Baptista, N., Alves, H., & Pinho, J. C. (2020b). Uncovering the use of the social support concept in social marketing interventions for health. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, in press(ahead-of-print), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2020.1760999

Baptista, N., Pinho, J. C., & Alves, H. (2021). Examining social capital and online social support links: A study in online health communities facing treatment uncertainty. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 18(1), 57–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-020-00263-2

Baptista, N. T., & Rodrigues, R. G. (2018). Clustering consumers who engage in boycotting: New insights into the relationship between political consumerism and institutional trust. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 15(1), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-018-0192-8

Barnes, D. C., Mesmer-Magnus, J., Scribner, L. L., Krallman, A., & Guidice, R. M. (2020). Customer delight during a crisis: Understanding delight through the lens of transformative service research. Journal of Service Management, 32(1), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-05-2020-0146

Barry, M. (2020). A critical refection on the enablers of transformative health promotion action. European Journal of Public Health, 30(Supplement_5). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa165.301.

Bennett, R. (2013). Elements, causes and effects of donor engagement among supporters of UK charities. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 10(3), 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-013-0100-1

Berry, L. L. (2019). Service guarantees have a place in health care. Annals of Internal Medicine, 170(2), 116. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-2412

Berry, L. L., & Bendapudi, N. (2007). Health care: A fertile field for service research. Journal of Service Research, 10(2), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670507306682

Bhattacharya, S. (2017). Does corporate social responsibility contribute to strengthen brand equity? An empirical study. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 14(4), 513–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-017-0185-z

Bianchi, E. C., Daponte, G. G., & Pirard, L. (2020). The impact of cause-related marketing campaigns on the reputation of corporations and NGOs. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-020-00268-x

Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of phsical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(April), 57–71.

Blocker, C. P., & Barrios, A. (2015). The transformative value of a service experience. Journal of Service Research, 18(3), 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670515583064

Bloomer, M. J., & Al-Mutair, A. (2013). Ensuring cultural sensitivity for Muslim patients in the Australian ICU: Considerations for care. Australian Critical Care, 26(4), 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2013.04.003

Bonelli, R., Dew, R. E., Koenig, H. G., Rosmarin, D. H., & Vasegh, S. (2012). Religious and spiritual factors in depression: Review and integration of the research. Depression Research and Treatment, 2012, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/962860

Campos-Andrade, C., Hernández-Fernaud, E., & Lima, M.-L. (2013). A better physical environment in the workplace means higher well-being? A study with healthcare professionals. Psyecology, 4(1), 89–110. https://doi.org/10.1174/217119713805088324

de Jesus, C. M., & Alves, H. M. B. (2019). Consumer experience and the valued elements in the three phases of purchase of a cultural event. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 16(2–4), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-019-00224-4

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1

Delener, N. (1994). Religious contrasts in consumer decision behaviour patterns: Their dimensions and marketing implications. European Journal of Marketing, 28(5), 36–53. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569410062023

Duggirala, M., Rajendran, C., & Anantharaman, R. N. (2008). Patient‐perceived dimensions of total quality service in healthcare. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 15(5), 560–583. https://doi.org/10.1108/14635770810903150

Edvardsson, B., Tronvoll, B., & Gruber, T. (2011). Expanding understanding of service exchange and value co-creation: A social construction approach. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(2), 327–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0200-y

Eid, R., & El-Gohary, H. (2015). The role of Islamic religiosity on the relationship between perceived value and tourist satisfaction. Tourism Management, 46, 477–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.08.003

Falter, M., & Hadwich, K. (2020). Customer service well-being: Scale development and validation. The Service Industries Journal, 40(1–2), 181–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1652599

Fam, K. S., Waller, D. S., & Erdogan, B. Z. (2004). The influence of religion on attitudes towards the advertising of controversial products. European Journal of Marketing, 38(5/6), 537–555. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560410529204

Feng, K., Altinay, L., & Olya, H. (2019). Social well-being and transformative service research: Evidence from China. Journal of Services Marketing, 33(6), 735–750. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-10-2018-0294

Flynn, B. B., Schroeder, R. G., & Sakakibara, S. (1995). The impact of quality management practices on performance and competitive advantage. Decision Sciences, 26(5), 659–691. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.1995.tb01445.x

Forsyth, D. R. (1980). A taxonomy of ethical ideologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(1), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.1.175

Forsyth, D. R. (1992). Judging the morality of business practices: The influence of personal moral philosophies. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(5–6), 461–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00870557

Friele, R. D., & Sluijs, E. M. (2006). Patient expectations of fair complaint handling in hospitals: Empirical data. BMC Health Services Research, 6(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-6-106

Friele, R. D., Sluijs, E. M., & Legemaate, J. (2008). Complaints handling in hospitals: An empirical study of discrepancies between patients’ expectations and their experiences. BMC Health Services Research, 8(1), 199. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-199

Frow, P., McColl-Kennedy, J. R., & Payne, A. (2016). Co-creation practices: Their role in shaping a health care ecosystem. Industrial Marketing Management, 56, 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.03.007

Gauthier, J. (2017). Sustainable business strategies: Typologies and future directions. Society and Business Review, 12(1), 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBR-01-2016-0005

Gonzalez-Mulé, E., & Aguinis, H. (2018). Advancing theory by assessing boundary conditions with metaregression: A critical review and best-practice recommendations. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2246–2273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317710723

Grönroos, C. (2011). Value co-creation in service logic: A critical analysis. Marketing Theory, 11(3), 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593111408177

Hamed, S., El-Bassiouny, N., & Ternès, A. (2017). Evidence-based design and transformative service research application for achieving sustainable healthcare services: A developing country perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140, 1885–1892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.161

Hays, J. M., & Hill, A. V. (2006). Service guarantee strength: The key to service quality. Journal of Operations Management, 24(6), 753–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2005.08.003

Heinonen, K., Strandvik, T., Mickelsson, K. J., Edvardsson, B., Sundström, E., & Andersson, P. (2010). A customer-dominant logic of service. Journal of Service Management, 21(4), 531–548. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231011066088

Henriksen, K., Isaacson, S., Sadler, B. L., & Zimring, C. M. (2007). The role of the physical environment in crossing the quality chasm. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 33(11 SUPPL.), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(07)33114-0

Hirschman, E. C. (1982). Religious Differences in Cognitions Regarding Novelty Seeking and Information Transfer. ACR North American Advances, NA-09. Retrieved from http://acrwebsite.org/volumes/5997/volumes/v09/NA-09. Accessed 31 May 2019.

Hogreve, J., & Gremler, D. D. (2009). Twenty years of service guarantee research. Journal of Service Research, 11(4), 322–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670508329225

Hopkins, C. D., Shanahan, K. J., & Raymond, M. A. (2014). The moderating role of religiosity on nonprofit advertising. Journal of Business Research, 67(2), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.03.008

Islam, S., Hoque, M. R., & Jamil, M. AAl. (2020). Predictors of users’ preferences for online health services. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 37(2), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-05-2018-2689

Islam, S., & Muhamad, N. (2021). Patient-centered communication: An extension of the HCAHPS survey. Benchmarking: An International Journal, ahead-of-p(ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-07-2020-0384

Jiménez-Castillo, D., Sánchez-Fernández, R., & Iniesta-Bonillo, M. Á. (2013). Segmenting university graduates on the basis of perceived value, image and identification. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 10(3), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-013-0102-z

Joiner, K., & Lusch, R. (2016). Evolving to a new service-dominant logic for health care. Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Health, 3, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.2147/IEH.S93473

Journal of Service Research Special Issue on Transformative Service Research: A Multidisciplinary Perspective on Service and Well-being. (2012). Journal of Service Research, 15(4), 363–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670512463639

Kalaignanam, K., & Varadarajan, R. (2012). Offshore outsourcing of customer relationship management: Conceptual model and propositions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(2), 347–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0291-0

Karande, K., Merchant, A., & Sivakumar, K. (2011). Erratum to: Relationships among time orientation, consumer innovativeness, and innovative behavior: The moderating role of product characteristics. AMS Review, 1(2), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-011-0009-y

Kennett-hensel, P. A., Min, K. S., & Totten, J. W. (2012). The impact of health-care service guarantees on consumer decision- making: An experimental investigation. Health Marketing Quarterly, 29(2), 146–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/07359683.2012.678258

Kuppelwieser, V. G., & Finsterwalder, J. (2016). Transformative service research and service dominant logic: Quo vaditis? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 28, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.08.011

Ladhari, R., Pons, F., Bressolles, G., & Zins, M. (2011). Culture and personal values : How they in fl uence perceived service quality. Journal of Business Research, 64(9), 951–957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.11.017

Linder-Pelz, S. (1982). Social psychological determinants of patient satisfaction: A test of five hypotheses. Social Science and Medicine, 16(5), 583–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(82)90312-4

McColl, E., Thomas, L., & Bond, S. (1996). A study to determine patient satisfaction with nursing care. Nursing Standard, 10(52), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.10.52.34.s47

Moons, P., Luyckx, K., Dezutter, J., Kovacs, A. H., Thomet, C., Budts, W., … Apers, S. (2019). Religion and spirituality as predictors of patient-reported outcomes in adults with congenital heart disease around the globe. International Journal of Cardiology, 274(July 2018), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.07.103

Muhamad, N., & Mizerski, D. (2007). Muslim religious commitment related to intention to purchase taboo products. Journal of Business and Policy Research, 3(1), 74.

Muhamad, N., & Mizerski, D. (2010). The constructs mediating religions’ influence on buyers and consumers. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 1(2), 124–135. https://doi.org/10.1108/17590831011055860

Ostrom, A. L., Parasuraman, A., Bowen, D. E., Patrício, L., & Voss, C. A. (2015). Service research priorities in a rapidly changing context. Journal of Service Research, 18(2), 127–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670515576315

Padela, A. I., & Curlin, F. A. (2013). Religion and disparities: Considering the influences of Islam on the health of American muslims. Journal of Religion and Health, 52(4), 1333–1345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9620-y

Parahoo, S. K., & Al-Nakeeb, A. A. (2019). Investigating antecedents of social innovation in public sector using a service ecosystem lens. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 16(2–4), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-019-00229-z

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(January), 12–40.

Patrício, L., Sangiorgi, D., Mahr, D., Čaić, M., Kalantari, S., & Sundar, S. (2020). Leveraging service design for healthcare transformation: Toward people-centered, integrated, and technology-enabled healthcare systems. Journal of Service Management, 31(5), 889–909. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-11-2019-0332

Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20015

Prebensen, N. K., Kim, H (Lina)., & Uysal, M. (2016). Cocreation as moderator between the experience value and satisfaction relationship. Journal of Travel Research, 55(7), 934–945. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515583359

Prentice, C., Altinay, L., & Woodside, A. G. (2021). Transformative service research and COVID-19. The Service Industries Journal, 41(1–2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2021.1883262

Raposo, M. L., Alves, H. M., & Duarte, P. A. (2009). Dimensions of service quality and satisfaction in healthcare: A patient’s satisfaction index. Service Business, 3(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-008-0055-1

Rashid, M., & Ahmad, F. (2014). Service recovery and satisfaction: The moderating role of religiosity. In Theory and Practice in Hospitality and Tourism Research (pp. 535–539). https://doi.org/10.1201/b17390-106

Rey-Moreno, M., Medina-Molina, C., & Barrera-Barrera, R. (2018). Multichannel strategies in public services: Levels of satisfaction and citizens’ preferences. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 15(1), 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-017-0188-9

Russell-Bennett, R., Fisk, R. P., Rosenbaum, M. S., & Zainuddin, N. (2019). Commentary: Transformative service research and social marketing – converging pathways to social change. Journal of Services Marketing, 33(6), 633–642. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-10-2018-0304

Russo, G., Moretta Tartaglione, A., & Cavacece, Y. (2019). Empowering patients to co-create a sustainable healthcare value. Sustainability, 11(5), 1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051315

Salonen, H., Lahtinen, M., Lappalainen, S., Nevala, N., Knibbs, L. D., Morawska, L., & Reijula, K. (2013). Physical characteristics of the indoor environment that affect health and wellbeing in healthcare facilities: A review. Intelligent Buildings International, 5(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508975.2013.764838

Sandström, S., Edvardsson, B., Kristensson, P., & Magnusson, P. (2008). Value in use through service experience. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 18(2), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520810859184

Sangiorgi, D. (2011). Transformative services and transformation design. International Journal of Design, 5(2), 29–40.

Seiders, K., Flynn, A. G., Berry, L. L., & Haws, K. L. (2015). Motivating customers to adhere to expert advice in professional services. Journal of Service Research, 18(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670514539567

Singhapakdi, A., Kraft, K. L., Vitell, S. J., & Rallapalli, K. C. (1995). The perceived importance of ethics and social responsibility on organizational effectiveness: A survey of marketers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23(1), 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02894611

Singhapakdi, A., Vitell, S. J., & Franke, G. R. (1999). Antecedents, consequences, and mediating effects of perceived moral intensity and personal moral philosophies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070399271002

Sirgy, M. J., Hansen, D. E., & Littlefield, J. E. (1994). Does hospital satisfaction affect life satisfaction? Journal of Macromarketing, 36(fall), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/027614679401400204

Sirgy, M. J., & Lee, D.-J. (2006). Macro measures of consumer well-being (CWB): A critical analysis and a research agenda. Journal of Macromarketing, 26(1), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146705285669

Sobh, R., & Perry, C. (2006). Research design and data analysis in realism research. European Journal of Marketing, 40(11–12), 1194–1209. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560610702777

Steinke, C. (2015). Assessing the physical service setting: A look at emergency departments. Health Environments Research and Design Journal, 8(2), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1937586714565611

Sureshchandar, G. S., Rajendran, C., & Anantharaman, R. N. (2002). Determinants of customer-perceived service quality: A confirmatory factor analysis approach. Journal of Services Marketing, 16(1), 9–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040210419398

Sweeney, J. C., Danaher, T. S., & McColl-Kennedy, J. R. (2015). Customer effort in value cocreation activities: Improving quality of life and behavioral intentions of health care customers. Journal of Service Research, 18(3), 318–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670515572128

Thompson, A. G., & Suñol, R. (1995). Expectations as determinants of patient satisfaction: Concepts, theory and evidence. International Journal for Quality in Health Care : Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 7(2), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/7.2.127

Tomes, A. E., & Chee Peng Ng, S. (1995). Service quality in hospital care: The development of an in-patient questionnaire. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 8(3), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/09526869510089255

Tremblay, M. (2020). Equality versus equity: Barriers to health care access for Indigenous populations in Canada. European Journal of Public Health, 30(Supplement_5). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa165.778

Troye, S. V., & Supphellen, M. (2012). Consumer participation in coproduction: “I made it myself” effects on consumers’ sensory perceptions and evaluations of outcome and input product. Journal of Marketing, 76(2), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.10.0205

Tucker, J. L., & Adams, S. R. (2001). Incorporating patients’ assessments of satisfaction and quality: An integrative model of patients’ evaluations of their care. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 11(4), 272–287. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005611

Ulrich, R. S., Berry, L. L., Quan, X., & Parish, J. T. (2010). A conceptual framework for the domain of evidence-based design. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 4(1), 95–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/193758671000400107

Ulrich, R. S., Zimring, C., Zhu, X., DuBose, J., Seo, H.-B., Choi, Y.-S., …, Joseph, A. (2008). A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 1(3), 61–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/193758670800100306

Van Rompay, T. J. L., & Tanja-Dijkstra, K. (2010). Directions in healthcare research: Pointers from retailing and services marketing. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 3(3), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/193758671000300309

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.1.1.24036

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2008). Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0069-6

Vitell, S. J., & Paolillo, J. G. P. (2004). A cross-cultural study of the antecedents of the perceived role of ethics and social responsibility. Business Ethics: A European Review, 13(2–3), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2004.00362.x

Vitell, S. J., Rallapalli, K. C., & Singhapakdi, A. (1993). Marketing norms: The influence of personal moral philosophies and organizational ethical culture. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 21(4), 331–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02894525