Abstract

The Subdural Hematoma in the Elderly (SHE) score was developed as a model to predict 30-day mortality from acute, chronic, and mixed subdural hematoma in the elderly population after minor or no trauma. Emerging evidence suggests frailty to be predictive of mortality and morbidity in the elderly. In this study, we aim to externally validate the SHE for chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) alone, and we hypothesize that the incorporation of frailty into the SHE may increase its predictive power. A retrospective cohort of elderly patients with CSDH after minor or no trauma being treated at our institution was evaluated with the SHE. Thirty-day mortality and outcome were documented. Patients were assessed with the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), which was incorporated into a modified SHE (mSHE). Both the SHE and the mSHE were then assessed in their predictive powers through receiver operating characteristic statistics. We included 168 patients. Most (n = 124, 74%) had a favorable outcome at 30 days. Mortality was low at n = 7, 4%. The SHE failed to predict mortality (AUC = .564, p = .565). Contrarily, the mSHE performed well in both mortality (AUC = .749, p = .026) and outcome (AUC = .862, p < .001). A threshold of mSHE = 3 is predictive of mortality with a sensitivity of 50% and a specificity of 75% and of poor outcome with a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 64%. Frailty should be routinely evaluated in elderly individuals, as it can predict outcome and mortality, providing the possibility for medical, surgical, nutritional, cognitive, and physical exercise interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, there has been a steady increase in the elderly population, and current projections estimate a total of > 1.5 billion individuals aged > 65 years by 2050 [1]. For neurosurgeons, this demographic trend presupposes a concomitant, continuous increase in patients suffering from a chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH), a condition traditionally associated with old age [2]. Epidemiologic studies have shown the incidence of CSDH to increase from 3.4/100,000/year in individuals < 65 years, to up to 58–127/100,000/year in the elderly [3]. Thus, CSDH in the elderly will become an even more prevalent pathology in neurosurgery in future decades.

Geriatric patients present unique challenges, as studies have shown age to be a predictor of poor outcome and mortality, irrespective of surgical discipline and pathology treated [4, 5]. Careful and comprehensive counseling of elderly patients and their families thus becomes pivotal in clinical decision-making. When deciding which patients should undergo further treatment of their CSDH, proper assessment of their prognosis is key. To aid clinicians in their decision-making and advising, the Subdural Hematoma in the Elderly (SHE) score was published in 2019 as a model to predict 30-day mortality from a subdural hematoma in the elderly population after minor or no trauma [6].

To develop this score, patients suffering from acute SDH (ASDH), chronic SDH (CSDH), and mixed-acuity SDH (MASDH) from a consecutive retrospective cohort were analyzed [7]. Admission Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), age, and hematoma volume were identified as predictive variables. Emerging evidence however suggests that the relationship between age and outcome is not necessarily clear-cut and linear. Frailty, an age-related cumulative decline in multiple physiological systems, has been shown to be a better predictor of mortality and morbidity than chronological age alone in multiple conditions [4]. Furthermore, ASDH and CSDH are distinct clinical entities with different underlying pathophysiologies and clinical courses: e.g., CSDH usually presents with subtle symptoms not necessarily reflected by GCS [8], while ASDH usually leads to rapid neurologic deterioration. In this study, we aim to externally validate the SHE for CSDH alone, excluding ASDH and MASDH. Furthermore, we hypothesize that the incorporation of frailty assessment into the SHE can increase its predictive power for mortality and outcome in elderly patients with CSDH.

Materials and methods

Patient population, inclusion, and exclusion criteria

We conducted a retrospective study of consecutive elderly patients admitted to our center with CSDH from January 2015 to September 2019. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, no informed consent was necessary. The study was carried out in accordance with our institutional protocols and the 1964 Helsinki declaration (IRB 15/1/21). In analogy to the methods used by Alford et al. [6], patients were considered to be “elderly” if they were > 65 years. As stipulated by the SHE, only patients with a history of minor or no trauma were included. Patients who had sustained high-velocity trauma, such as a fall from a height > 3 m, motor-vehicle accident, or pedestrian struck were excluded. Baseline demographic characteristics, GCS at admission, and hematoma volume, as calculated by the A*B*C/2 formula, were recorded and scored according to the SHE. Additionally, presenting symptoms were evaluated by means of the Markwalder Grading System (MGS) for CSDH. All patients included were initially treated by means of minimally invasive twist-drill-craniostomy (TDC) under local anesthesia, as described by Reinges et al. [9].

Frailty assessment and the modified SHE

To test our hypothesis, we assessed patients by means of the Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CSHA) Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) [10, 11] (Table 1), a tool that has been validated for retrospective application [12]. We chose this scale because it was shown to correlate with outcome in a logistic regression analysis in a retrospective series of 211 CSDH elderly patients [13]. Thus, we maintained the same methodology for variable selection employed by Alford et al. in their original publication [6], namely the Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) and the Transparent Reporting of a multivariate prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) [14].

We included the CFS in the modified SHE (mSHE), allotting 0 points for CFS 1–3, 1 point for CFS 4–5, and 2 points for CFS 6–9. These thresholds were derived from retrospective validation studies, in which the CFS was evaluated in its ability to identify patients who would benefit from intensive care management [15] or resuscitation after cardiac arrest [16]. Table 2 summarizes the components of the SHE and the mSHE.

Outcome

Since the SHE was developed to predict 30-day mortality in SDH patients, we collected data on mortality in our patient population as the primary endpoint of this study. Furthermore, we assessed patient outcome at 30 days by means of the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) as a secondary endpoint. The outcome was dichotomized in “good” for GOS ≥ 4 and “poor” for GOS ≤ 3.

Statistical analysis

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were calculated for the SHE and the mSHE, for both mortality and dichotomized outcome (“good”/”poor”) in CSDH. Statistical significance was assumed at p < 0.05. Youden’s index was used to determine the best cutoff values in the SHE and the mSHE for the prediction of mortality and outcome. Analysis was performed using IBM® SPSS® v. 21.

Results

A total of 168 patients were included. Of these, n = 112, 67% were males. Median age was 79 years (interquartile range (IQR) 10.75). Most patients, n = 103, 61%, were on anticoagulants and/or antiaggregants. Clinically, n = 60, 36% presented with mild symptoms (MGS 0–1), n = 63, 38% with moderate symptoms (MGS 2) and n = 45, 27% with severe symptoms (MGS 3–4). Median hematoma volume was 121 ml (IQR 79).

Most patients (n = 124, 74%) had a favorable outcome of GOS 4–5 at 30 days. Mortality was low at n = 7, 4% in the entire cohort. As illustrated in Fig. 1, good outcome was observed in 75% of patients with SHE = 0, 88% with SHE = 1, 76% with SHE = 2, 21% in SHE = 3, and 0% with SHE = 4. For mSHE, good outcome was 100% at mSHE = 0, 97% at mSHE = 1, 85% at mSHE = 2, 60% at mSHE = 3, 33% at mSHE = 4, and 0% at mSHE = 5. Patients with SHE = 4 had 0% mortality. The distribution of outcome according to SHE/mSHE is summarized in Table 3.

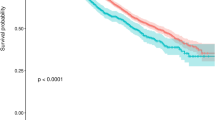

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the SHE failed to predict mortality in our patient cohort (AUC = 0.564, p = 0.565), but it was a sensitive prognostic tool for outcome, as objectivized by GOS (AUC = 0.740, p < 0.001*). On the contrary, the mSHE performed well in both mortality (AUC = 0.749, p = 0.026*) and outcome prediction (AUC = 0.862, p < 0.001*). A threshold of mSHE = 3 is predictive of mortality with a sensitivity of 50% and a specificity of 75%; the same threshold is predictive of poor outcome with a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 64%.

Discussion

In our cohort, the SHE was not a statistically significant model to predict 30-day mortality in CSDH. In the original publication by Alford et al. [6], the score also performed the worst in the CSDH subgroup, with an AUC of 0.8, compared to an AUC of 0.941 in ASDH. With almost twice as many patients with CSDH than the original cohort, 168 vs. 89, we could not validate the SHE for 30-day mortality prediction in CSDH. Thus, we recommend caution when relying on this model alone to guide clinical decision-making and counseling in patients with CSDH after no or minor trauma.

The authors postulate that their inability to validate the SHE was due to a methodological limitation of the original work, namely the pooling of patients with ASDH, MASDH, and CSDH from a retrospective study by Kuhn et al. [7]. In this study, mortality predictors from a multivariate analysis in the ASDH cohort were different from those in CSDH. GCS on admission, contusion volume, and age ≥ 80 years were predictive of mortality in ASDH. In the CSDH cohort, only GCS was associated with increased mortality. Evidently, the SHE relies on predictors more strongly associated with ASDH and obviates potential additional factors exclusively related to CSDH.

The observed differences in predictive factors in the study by Kuhn et al. [7] can be at least partially explained by the differing pathophysiologies of the hematoma types. On the one hand, ASDH is often associated with a rapid neurological decompensation and deterioration, due to the pooling of blood in the subdural space after tears in bridging veins or, in the majority, superficial cortical arteries, classically resulting from traumatic brain injury [17]. In the elderly, these tears can, and often do, result from minor trauma, such as falls while walking or from bed [18].

CDSH, on the other hand, is associated with neuroinflammatory processes. While the initial insult might be minor trauma, such as in ASDH, an inflammatory cascade with accompanying neo-angiogenesis, fibrinolysis, and excessive fluid exudation from newly formed membranes following an oncotic gradient characterizes this condition and explains its latency in clinical presentation and tendency to recurrence [19, 20]. Patients thus present with more subtle neurological symptoms [8, 21], and the natural history of this condition is often insidious [3]. Nevertheless, CSDH in the elderly has been termed a “sentinel health event,” heralding underlying systemic pathology in this patient population [2].

Notably, the mortality rate in ASDH in the elderly can be up to 60% [17, 18, 22]. In contrast, the mortality rate in CSDH in geriatric populations is almost half, at up to 32% [23, 24]. While mortality in ASDH can be attributed to the underlying brain injury and increased intracranial pressure [17, 18], mortality in CSDH varies greatly in its causes. Overall in-hospital mortality during index admission has been reported at 16% due to complications such as rebleeding, respiratory failure, and dementia; this rate rises to up to 32% at 6 months, with iatrogenic complications such as pulmonary embolism, stroke, or myocardial infarction taking on a more predominant role due to the discontinuation of anticoagulants in a highly comorbid population [25]. These greatly differing mortality rates provide further explanation as to why pooling patients with these two separate clinical entities for prediction modeling might not be advisable. Nonetheless, among neurosurgeons, CSDH is generally recognized as a benign condition and underestimation of fatality risk is common.

Another potential reason for our inability to externally validate the SHE for mortality prediction in CSDH might lie in the differing treatment algorithms. At our center, all patients with CSDH undergo TDC under local anesthesia as first-line surgical treatment [9]. In the original work by Kuhn et al. [7], on which the SHE was based, patients were treated by means of craniotomies, burr-hole evacuation, and minimally invasive techniques. A detailed subgroup analysis based on surgical techniques was not performed. Studies have failed to prove the superiority of one surgical technique over another, and medical management remains controversial [2, 26, 27]. In a systematic review by Ivamoto et al. [28], TDC and burr-hole evacuation were found to be equivalent. In a meta-analysis by Weigel et al. [29], all surgical techniques were found to have similar mortality (2–4%), but craniotomy was shown to have significantly higher morbidity than TDC. Seizures, empyema, pneumonia, and other medical complications more often ensue after more invasive surgical procedures [30]. Nevertheless, it is well established that geriatric patients have an increased risk for adverse outcomes when undergoing general anesthesia due to their comorbidities, polypharmacy, and decreased physiological reserve [5, 31]. Thus, the outcome in elderly patients undergoing treatment for CSDH can be greatly influenced by surgical and anesthetic techniques, which is not accounted for in the study by Kuhn et al. [7], and thus by the SHE. Due to our institutional protocols dictating TDC as first-line treatment for CSDH, our study population is more homogeneous, thus removing this potential confounder when evaluating scoring systems.

A main result of our study is that by incorporating frailty assessment into the SHE, we were able to increase its accuracy in mortality prediction in our patient cohort. Frailty is a geriatric syndrome characterized by decreased functional reserve and increased vulnerability against stressors [32]. It results from the cumulative decline of many physiological systems during a lifetime, and it is not necessarily dependent on other distinct comorbidities; it rather reflects their impact on the organism [12]. A study by Shimizu et al. [13] on 211 elderly patients with CSDH showed that those with frailty, objectivized by means of the CFS, had a poorer prognosis than those without. A systematic review of the literature on ASDH in the elderly [33] identified the presence of comorbidities to influence the outcome but also evinced the lack of literature objectively assessing comorbidities and frailty with validated instruments. While the evidence is only beginning to emerge on the importance of frailty assessment in CSDH, recent studies have illustrated how it can aid clinicians in prognostication in other neurosurgical pathologies, including glioblastoma [34], meningioma [35], and other primary central nervous system tumors [36]. Thus, the inclusion of this additional criterion into prognostication tools in CSDH appears warranted.

Alford et al. [6] suggest the SHE might be superior to other existing prediction models for SDH [37] thanks to the simplicity and readily availability of its components. The CFS is an easy-to-use scale, amply validated [10, 38] in multiple settings, both in medicine and surgery, so that the authors believe that its incorporation into the SHE does not make it more cumbersome.

Importantly, frailty is not an irreversible pathology, and it can be improved upon. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials showed that physical exercise interventions in frail elderly individuals can improve their outcomes [39]. Additionally, nutritional and cognitive interventions can reverse frailty [40]. Therefore, frailty assessment provides a tremendous opportunity for risk stratification and the incorporation of early, aggressive rehabilitation programs to optimize patient outcome. Scoring systems and clinical prediction models are critical to inform and counsel patients and their families. With the mSHE, the authors believe that clinicians can guide patients not only about CSDH, but also about the necessary rehabilitation interventions to recover from it.

Limitations

This study has several limitations due to its retrospective nature. The data obtained from medical records might be inaccurate, especially when relying on them to extract the degree of frailty and judging on the outcome using GOS in a retrospective manner. In particular, due to the insidious nature of CSDH, the degree of frailty might have been misjudged, for CSDH might have had an unrecognized effect on the patient’s independence and physiological reserve before neurosurgical consultation. Finally, we did not assess the social network of the patients, which might have had an impact on their outcome.

Conclusion

We failed to externally validate the SHE for mortality prognostication in elderly individuals suffering from CSDH. Thus, the authors warrant caution when relying on this model alone for patient counseling. By incorporating an objective, easy-to-perform clinical frailty assessment into the SHE, we were able to increase its performance and predict both mortality and outcome in geriatric patients with CSDH. Frailty should therefore be routinely evaluated in elderly individuals, for it can aid clinicians, caregivers, and patients develop a holistic therapeutic approach, including medical, surgical, nutritional, cognitive, and physical exercise interventions.

Data availability

Pertinent data are presented in the manuscript. Raw data can be made available at request pseudonymized.

Code availability

N/A.

References

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019) World population ageing 2019: highlights. United Nations, New York

Shapey J, Glancz LJ, Brennan PM (2016) Chronic subdural haematoma in the elderly: is it time for a new paradigm in management? Curr Geriatr Rep 5:71–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-016-0166-9

Yang W, Huang J (2017) Chronic subdural hematoma: epidemiology and natural history. Neurosurg Clin N Am 28:205–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nec.2016.11.002

Lin HS, Watts JN, Peel NM, Hubbard RE (2016) Frailty and post-operative outcomes in older surgical patients: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 16(1):157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0329-8

Maxwell CA, Patel MB, Suarez-Rodriguez LC, Miller RS (2019) Frailty and prognostication in geriatric surgery and trauma. Clin Geriatr Med 35:13–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2018.08.002

Alford EN, Rotman LE, Erwood MS, Oster RA, Davis MC, Pittman BHC, Zeiger HE, Fisher WS (2020) Development of the Subdural Hematoma in the Elderly (SHE) score to predict mortality. J Neurosurg 132:1616–1622. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.1.JNS182895

Kuhn EN, Erwood MS, Oster RA, Davis MC, Zeiger HE, Pittman BC, Fisher WS (2018) Outcomes of subdural hematoma in the elderly with a history of minor or no previous trauma. World Neurosurg 119:e374–e382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.07.168

Uno M, Toi H, Hirai S (2017) Chronic subdural hematoma in elderly patients: is this disease benign? Neurol Med Chir 57:402–409. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmc.ra.2016-0337

Reinges MHT, Hasselberg I, Rohde V, Küker W, Gilsbach JM (2000) Prospective analysis of bedside percutaneous subdural tapping for the treatment of chronic subdural haematoma in adults. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 69:40–47. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.69.1.40

Pulok MH, Theou O, van der Valk AM, Rockwood K (2020) The role of illness acuity on the association between frailty and mortality in emergency department patients referred to internal medicine. Age Ageing 49(6):1071–1079. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaa089

Rockwood K, Mitnitski A (2007) Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 62:722–727. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/62.7.722

Wallis SJ, Wall J, Biram RWS, Romero-Ortuno R (2015) Association of the clinical frailty scale with hospital outcomes. QJM 108:943–949. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcv066

Shimizu K, Sadatomo T, Hara T, Onishi S, Yuki K, Kurisu K (2018) Importance of frailty evaluation in the prediction of the prognosis of patients with chronic subdural hematoma. Geriatr Gerontol Int 18:1173–1176. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13436

Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KGM (2015) Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD) the TRIPOD statement. Circulation 131:211–219. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014508

Scale CF, Cfs T, Scale CF (2020) Clinical Frailty Scale in prediction of mortality, disability and quality of life for patients in need of intensive care. 1–21

Ibitoye SE, Rawlinson S, Cavanagh A, Phillips V, Shipway DJH (2020) Frailty status predicts futility of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in older adults. Age Ageing 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaa104

Hsieh CH, Rau CS, Wu SC, Liu HT, Huang CY, Hsu SY, Hsieh HY (2018) Risk factors contributing to higher mortality rates in elderly patients with acute traumatic subdural hematoma sustained in a fall: a cross-sectional analysis using registered trauma data. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(11):2426. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112426

Taussky P, Hidalgo ET, Landolt H, Fandino J (2012) Age and salvageability: analysis of outcome of patients older than 65 years undergoing craniotomy for acute traumatic subdural hematoma. World Neurosurgery 78:306–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2011.10.030

Castellani RJ, Mojica-Sanchez G, Schwartzbauer G, Hersh DS (2017) Symptomatic acute-on-chronic subdural hematoma a clinicopathological study. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 38:126–130. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAF.0000000000000300

Edlmann E, Giorgi-Coll S, Whitfield PC, Carpenter KLH, Hutchinson PJ (2017) Pathophysiology of chronic subdural haematoma: inflammation, angiogenesis and implications for pharmacotherapy. J Neuroinflammation 14:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-017-0881-y

Ishikawa E, Yanaka K, Sugimoto K, Ayuzawa S, Nose T (2002) Reversible dementia in patients with chronic subdural hematomas. J Neurosurg 96:680–683. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2002.96.4.0680

Kerezoudis P, Goyal A, Puffer RC, Parney IF, Meyer FB, Bydon M (2020) Morbidity and mortality in elderly patients undergoing evacuation of acute traumatic subdural hematoma. Neurosurg Focus 49:E22. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.7.FOCUS20439

Kolias AG, Chari A, Santarius T, Hutchinson PJ (2014) Chronic subdural haematoma: modern management and emerging therapies. Nat Rev Neurol 10:570–578. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.163

Wang S, Ma Y, Zhao X, Yang C, Gu J, Weng W, Hui J, Mao Q, Gao G, Feng J (2019) Risk factors of hospital mortality in chronic subdural hematoma: a retrospective analysis of 1117 patients, a single institute experience. J Clin Neurosci 67:46–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2019.06.026

Edlmann E, Hutchinson PJ, Kolias AG (2017) Chronic subdural haematoma in the elderly. Brain Spine Surg Elderly 353–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40232-1_20

Iorio-Morin C, Touchette C, Lévesque M, Effendi K, Fortin D, Mathieu D (2018) Chronic subdural hematoma: toward a new management paradigm for an increasingly complex population. J Neurotrauma 35:1882–1885. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2018.5872

Scerrati A, Visani J, Ricciardi L, Dones F, Rustemi O, Cavallo MA, de Bonis P (2020) To drill or not to drill, that is the question: nonsurgical treatment of chronic subdural hematoma in the elderly. A systematic review. Neurosurg Focus 49:E7. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.7.FOCUS20237

Ivamoto HS, Lemos HP, Atallah AN (2016) Surgical treatments for chronic subdural hematomas: a comprehensive systematic review. World Neurosurg 86:399–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2015.10.025

Brodbelt A, Warnke P, Weigel R, Krauss JK (2004) Outcome of contemporary surgery for chronic subdural haematoma: evidence based review [3] (multiple letters). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 75:1209–1210

Rohde V, Graf G, Hassler W (2002) Complications of burr-hole craniostomy and closed-system drainage for chronic subdural hematomas: a retrospective analysis of 376 patients. Neurosurg Rev 25:89–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s101430100182

Steinmetz J, Rasmussen LS (2010) The elderly and general anesthesia. Minerva Anestesiol 76:745–752

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A (2005) A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 173:489–495. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050051

Evans LR, Jones J, Lee HQ, Gantner D, Jaison A, Matthew J, Fitzgerald MC, Rosenfeld JV, Hunn MK, Tee JW (2019) Prognosis of acute subdural hematoma in the elderly: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma 36:517–522. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2018.5829

Katiyar V, Sharma R, Tandon V, Goda R, Ganeshkumar A, Suri A, Chandra PS, Kale SS (2020) Impact of frailty on surgery for glioblastoma: a critical evaluation of patient outcomes and caregivers’ perceptions in a developing country. Neurosurg Focus 49:E14. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.7.FOCUS20482

Theriault BC, Pazniokas J, Adkoli AS, Cho EK, Rao N, Schmidt M, Cole C, Gandhi C, Couldwell WT, Al-Mufti F, Bowers CA (2020) Frailty predicts worse outcomes after intracranial meningioma surgery irrespective of existing prognostic factors. Neurosurg Focus 49:E16. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.7.FOCUS20324

Shahrestani S, Lehrich BM, Tafreshi AR, Brown NJ, Lien B, v., Ransom S, Ransom RC, Ballatori AM, Ton A, Chen XT, Sahyouni R, (2020) The role of frailty in geriatric cranial neurosurgery for primary central nervous system neoplasms. Neurosurg Focus 49:E15. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.7.FOCUS20426

Kwon CS, Al-Awar O, Richards O, Izu A, Lengvenis G (2018) Predicting prognosis of patients with chronic subdural hematoma: a new scoring system. World Neurosurg 109:e707–e714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.10.058

O’Caoimh R, Costello M, Small C, Spooner L, Flannery A, O’Reilly L, Heffernan L, Mannion E, Maughan A, Joyce A, William Molloy D, O’Donnell J (2019) Comparison of frailty screening instruments in the emergency department. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16:1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193626

de Labra C, Guimaraes-Pinheiro C, Maseda A, Lorenzo T, Millán-Calenti JC (2015) Effects of physical exercise interventions in frail older adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials Physical functioning, physical health and activity. BMC Geriatr 15:154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0155-4

Ng TP, Feng L, Nyunt MSZ, Feng L, Niti M, Tan BY, Chan G, Khoo SA, Chan SM, Yap P, Yap KB (2015) Nutritional, physical, cognitive, and combination interventions and frailty reversal among older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med 128:1225-1236.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.06.017

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Alisa von Seydlitz-Kurzbach, MD, and Christina Wolfert, MD, for their support in data acquisition.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

- S.H.D.: Study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

- D.B.: Analysis and interpretation of data, review of the manuscript

- V.R.: Study supervision, interpretation of data, review of the manuscript

- C.V.D.B.: Study concept, analysis and interpretation of data, and review of the manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was approved by our local ethics committee (15/1/21) and carried out according to the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

Consent to participate

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, no explicit informed consent was obtained from subjects.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

Veit Rohde receives personal fees from Aesculap and Storz outside this work. All other authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hernández-Durán, S., Behme, D., Rohde, V. et al. A matter of frailty: the modified Subdural Hematoma in the Elderly (mSHE) score . Neurosurg Rev 45, 701–708 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-021-01586-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-021-01586-2