Abstract

In recent decades, many higher education systems around the world have been exposed to institutional mergers. While the rationale for mergers has often been related to issues of improved quality, effectiveness and/or efficiency at the institutional level, fewer studies have analysed how mergers may affect institutional diversity within the higher education landscape. Focusing on institutional missions, the current study analyses the strategic plans of both merged and non-merged institutions in Norway. The key finding is that mergers may not necessarily reduce system level diversity, although mergers indeed may affect the organisational mission of individual institutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mergers have become commonplace in higher education, reflecting perceived needs for structural changes that can boost the effectiveness, efficiency or quality of the institutions affected (Cai et al., 2016). The literature on mergers in higher education has identified several factors influencing the merger process regarding the success of the implementation process as well as outcomes. Voluntary mergers (De Boer et al., 2017) as well as mergers within sectors seem to be more successful than mergers across sectors (Cai et al., 2016). Governance, structural features such as geography and size and factors such as leadership are other important variables in determining the success of a merger process (Kyvik & Stensaker, 2013; Välimaa et al., 2014). Studies have also shown the importance of the difference between the merged institutions regarding history, values and culture (Norgård & Skodvin, 2002). Finally, studies have shown that mergers are costly (Locke, 2007) and in need of long-term effort (Pritchard & Williamson, 2008).

However, in the merger literature, less research has been devoted to how mergers influence system level characteristics including the diversity of the higher education system (although system diversity issues are frequently discussed at a more generic level (see Huisman, 1995; Huisman et al., 2015). Wollscheid and Røsdal (n.d.)(work in progress) find that most studies address factors related to merger decisions at the meso level, including efficiency (Johnes & Tsionas, 2019), research productivity (Liu et al., 2018), branding, leadership and management (Harman & Harman, 2003; Skodvin, 1999). Mergers in higher education have been primarily motivated by arguments of efficiency (Harman & Harman, 2003) and quality enhancement (Frølich et al., 2016) related to academic standards (Wollscheid & Røsdal, n.d., work in progress).

While the literature on system level characteristics including contributions such as Clark (1983), Kyvik (2004) and Huisman and Van Vught (2009) describe national systems of higher education and how policies aim at altering these by introducing, for example, unified or binary systems, thereby influencing systems diversity. The merger literature explores mergers as a policy tool to enhance quality and relevance; here less attention has been directed to how institutional strategies post-mergers result in a diversified system. The latter is somewhat surprising as many merger initiatives also tend to be linked to policy agendas addressing the need for academic excellence as well as societal relevance (de Boer et al., 2017). Higher education systems can be designed to allow for fulfilment of these policy goals in different ways. Yet, the consequences of post-merger processes on institutional landscapes are to our knowledge less explored.

From a policy perspective, it is important to understand the system level impact of institutional mergers. Such processes may have significant consequences with respect to the division of labour between institutions—i.e. system diversity—a feature often seen as a key characteristic of higher education systems able to cater for multiple expectations and societal needs (Clark, 1983; van Vught, 2009). Obtaining such system diversity is still a challenge for policymakers—especially in higher education systems where individual institutions have considerable autonomy. For individual institutions facing a high degree of uncertainty, merger processes could be imagined as resulting in what some label as ‘institutional drift’ (Kyvik, 2009), where opportunities for taking on new missions and profiles can make sense from an institutional perspective, but where the system level effect could be reduced institutional diversity (Morphew et al., 2018). Based on this, we argue that it is important to study how mergers influence systems diversity, to inform policies and the field of practice. Furthermore, our contribution to the merger literature is important because we address not only individual mergers between two or more higher education institutions but explore the consequences of several individual mergers on the system level post-merger. Most merger studies depart from policy objectives and investigate mergers as cases which could fulfil predefined policy objectives, while we explore the post-merger consequences for an important policy goal which has rarely been addressed. Thus, our ambition is to add to studies of system diversity by drawing on insights from studies of institutional missions. Such a contribution is valuable to the field of higher education research because it connects organisational studies with the highly relevant policy problem of understanding system dynamics and policy outcomes of merger reforms.

Academic excellence and societal relevance can be interpreted as two rather generic ambitions that higher education institutions exposed to mergers need to manage. In voluntary mergers where institutions have considerable discretion deciding upon their future identity, mission and profile, how academic excellence and societal relevance should be managed is more of an open question. In principle, one could argue that institutions may have three basic strategic options: they may focus on either excellence or relevance, or alternatively try to balance these elements.

Thus, how do institutional mergers affect system level diversity? We investigate this question by analysing how institutional missions have transformed over time in the Norwegian higher education system—a system which has experienced major merger processes over the last decade. By studying change over time in mission statements and strategic plans in both merged and non-merged institutions, the current study sheds light on (i) the role mergers may play in fostering diversity in higher education systems, and (ii) the processes fostering institutional stability and change at institutional level.

Why apply institutional mission as a lens to explore diversity? Mergers include two or more higher education institutions becoming one new organisational unit. The concept of institutional mission allows us to explore how merger processes balance competing demands as new missions most likely reflect both historic characteristics of the involved institutions, expectations from national authorities and anticipations concerning the positioning of the new institution in a reshaped sector. However, in this study, we are not focusing on what the specific choices of individual institutions are doing with respect to this balance, but the result of all choices at system level. A key assumption guiding this study is that a system which allows for much diversity in organisational missions is an effective one—in the sense that it caters for a multiplicity of needs (Clark, 1983; van Vught, 2009), while a system containing institutions with less diverse missions is less effective. Whether merger processes add to or reduce system level diversity is thus an interesting issue to investigate.

Mergers and missions: a theoretical reflection

Organisational mergers—driving complexity?

While mergers have become commonplace in higher education, they are far from being trivial processes. Research has demonstrated that both intrinsic and extrinsic factors play important roles in merger processes (Kyvik & Stensaker, 2013; Norgård & Skodvin, 2002; Pritchard & Williamson, 2008). Some of these factors can be said to be quite consistent and difficult to ignore for those institutions involved in merger processes. For example, due to the current emphasis on global competition and the academic excellence, perceived as vital to survive in this situation, merging institutions may want to develop missions and profiles that reflect global images of ‘world-class’ institutions (Välimaa et al., 2014). Other factors may be intrinsic and related to institutional characteristics, historical legacies or disciplinary scope (de Boer et al., 2017).

Consistent intrinsic and extrinsic factors such as these may sometimes develop into what Thornton and Occasio (1999) label as an institutional logic. Thornton and Ocasio (1999; 2008: 101) argue that internal and external structures, norms and symbols are three integrated dimensions of an institutional logic. A core assumption in this perspective is that agency—identities, values and assumptions—of individuals and organisations is embedded in persistent patterns of attitudes, behaviour and sense-making. Means and ends of individuals and organisations are enabled and constrained by these logics (Thornton & Ocasio, 2008: 103). Skelcher and Smith (2015: 437) argue that these ‘logics give identity and meaning to actors, while at the same time the contradictions inherent in the plurality of logics provide the space for actors to elaborate’.

Based on this, one can expect that merger processes are embedded in a range of different logics that can result in both tradition and transformation. Examples include institutional characteristics of the merging higher education institutions, such as the extent of fragmentation and the extent to which they are their previous organisation reflect inherent knowledge specialisations (Parsons & Platt, 1973) or disciplinary profiles (Seeber et al., 2019). As academic authority, and consequently much power, traditionally being located at the lower levels of the organisation, merger processes may also be difficult to coordinate and govern (Paradeise et al., 2009; see also Clark, 1983), potentially resulting in hybrid or expanding profiles and institutional missions. As indicated earlier, strengthened ‘rationalisation’ of higher education institutions may nevertheless also influence merger processes, as a more professional management and leadership may try to affect merger processes responding to perceived societal and policy expectations (Krücken & Meier, 2006), including those that prioritise academic excellence (Ramirez, 2010). However, extrinsic expectations may not necessarily be coherent, and merger processes may consequently be exposed to conflicting demands resulting in ‘penetrated’ merger processes creating internal tensions which may reduce hierarchical control (Bleiklie et al., 2015).

Hence, while higher education institutions even in their ‘normal mode’ often are highly complex (Paradeise et al., 2009), one could argue that merger processes add substantially to this complexity (Battilana & Lee, 2014).

Organisational missions: managing complexity?

If mergers drive complexity, one could argue that missions and strategies are key organisational tools for managing this complexity. These concepts are closely interrelated in that missions are linked to what institutions intend to do and how they should be positioned within a specific field, while strategies contain information on how to get there (Morphew & Hartley, 2006).

The jury is still out on whether missions and strategies are effective organisational tools. An instrumental perspective—leaning heavily on research suggesting that higher education institutions have been transformed into more governed institutions (Frølich et al., 2016)—would suggest that formal missions and strategic plans are taken seriously, have budget consequences and are followed up by the institutional leadership (Morphew et al., 2018). This perspective would, in principle, emphasise that mergers would result in a new and distinct mission (Foster et al., 2017). Furthermore, such an overarching mission could create staff identification and build support and legitimacy for the merger. Gertsen and Zolner (2014) found, e.g. that organisational identification (to a given mission) may be enhanced across socio-cultural contexts and backgrounds of individual and professional groups—a finding of much relevance to merger processes.

An institutional perspective—inclined to acknowledge the incremental nature of change in higher education institutions due to inherent characteristics (Stensaker, 2015)—would on the other hand point to the symbolic nature of missions and strategies (Morphew & Hartley, 2006). The argument being that such tools are difficult to avoid due to the need for external legitimacy, but that there might be few links between stated ambitions and their implementation (Seeber et al., 2019). This perspective would suggest that mergers would produce missions that are externally legitimate, and that it would be difficult to develop more distinct, alternative missions as a result (Morphew et al., 2018).

However, Glynn (2008) has suggested that it is possible to identify combinations of instrumental and institutional perspectives—not least, as the need for external legitimacy increasingly is linked to specific results and outcomes. This situation makes ‘symbolic’ actions more difficult (see also Stensaker, 2015). Consequently, a hybrid perspective would emphasise that missions and strategies are increasingly influenced by the need for demonstrating links to institutional heritage, organisational identity and organisational memory—dimensions often embedded in an institutional perspective (Balmer & Burghausen, 2015). Bennett et al. (2016) have furthermore explored how leaders experience uncertainty and how they develop a capability for dealing with uncertainty referring amongst others to their sense of effective sense-making of external demands. Thus, in principle, the hybrid perspective opens for mergers leading to more generic, overarching, and even multiple missions (De Bernardis & Giustiniano, 2015; see also Seeber et al., 2019).

In this paper, we are interested in how institutional mergers affect system level diversity. We will investigate this by analysing how institutional missions have transformed over time. The three theoretical perspectives offered above provide different explanation regarding system diversity following mergers. These are summarised in the following expectations (Table 1).

Policy context, system characteristics, methodological approach and data

The Norwegian higher education system is the empirical context for the current study. This system is interesting as it has experienced a high number of mergers during recent decades, which allows us to explore to what extent the mergers have influenced system diversity. The empirical focus of the current study is the most recent mergers taking place as a result of the so-called structural reform of the system, where the Ministry of Education encouraged all institutions to identify potential partners and engage in mergers intended to result in more academically solid and societally relevant institutions (de Boer et al., 2017). Organisational redesign often forms part of policies launched to enhance system performance in higher education (De Boer et al., 2017). As a result of the Structural Reform in Norwegian higher education launched in April 2015 in the White Paper ‘Concentration for Quality’ (Kunnskapsdepartementet, 2014–2015), a large-scale organisational redesign of the higher education landscape is ongoing. As a result of the reform, the number of higher education institutions is significantly reduced. The mergers represent a new dynamic as they encompass mergers between different types of institutions (universities and university colleges), often across large geographic distances, creating large multi-campus institutions. The merger processes represent both horizontal (similar institutions, e.g. multiple university colleges) and vertical (universities ‘take-over’ over earlier university colleges) types (Harman & Harman, 2003). The redesign of the higher education landscape through mergers meant a gradual change from inter-institutional to intra-institutional variation. The Structural Reform focuses on a variety of politically desirable but not necessarily internally consistent objectives (e.g. high-quality education and research, robust academic environments, good access to education and competence, regional development, world leading academic environments and efficient use of resources). The reform aligns with the generic objectives behind structural reform initiatives, governments across the world aim to increase quality, efficiency (rationalisation/standardisation) and competitiveness through concentration of resources and diversification of the system. However, the White Paper also underlined that the merger processes was not aimed at reducing the overall diversity in the system. The ministry did not specify which institutions should merge; it was left to the institutions themselves to find merger partners. In practice, this way of structuring the policy process led to a number of new types of institutions in the Norwegian higher education landscape which may influence the traditional division of labour in the system between university colleges directed at societal relevance and universities directed at academic excellence. The Norwegian merger reform history may be a long-term government effort that, to varying extent and with varying force, has sought to order and simplify the landscape through standardising and mergers. Nevertheless, the 2015 Structural reform marked a clear milestone and introduced several new dynamics to the system. The process started in 2014, when the Ministry of Education and Research asked the higher education institutions to rethink their position in a future Norwegian higher education landscape consisting of fewer institutions (Frølich et al., 2016). In response, the institutions considered their preferred future strategic positions as well as steps to reach these positions. Based on inputs from higher education institutions, the 2015 White paper put forward five mergers of 14 institutions. The White Paper did not directly coerce institutions to merge, those that ‘did not fit into a voluntary merger were given the status of “mergers for further consideration” or “future location based on new quality measures”’ (Frølich et al., 2016: 2).

The merger processes that followed included the following:

-

Mergers between former university colleges, creating larger university colleges

-

Mergers between former university colleges, resulting in new universities

-

Merges between former university colleges and established universities, resulting in larger universities

All mergers resulted in quite complex multi-campus colleges and universities. Six institutions coming out of these merger processes make up the key cases for the present study (INN, NORD, HVL, USN, UiT and NTNU). As the Norwegian government initiating the mergers emphasised both academic excellence and social relevance, we have analysed mission statements and strategic plans of the newly merged institutions to study the visibility of these two dimensions in the strategic plans and mission statements of the six institutions, both before the merger process and after the merger was completed and a new institution was formed. Excellence and relevance are on the one hand key dimensions for understanding past missions of the institutions involved in the merger process, as relevance was a central element in the historical missions of university colleges, while excellence was a central element in the historical mission of many of the universities in Norway. However, excellence and relevance are also key to understanding future missions, as the coming together of these dimensions in more strategic, larger and more agile institutions was a key inspiration behind the structural reform.

In Norwegian higher education, mission statements are most often found within the strategic plan, but the strategic plans of institutions are also expected to be adapted to and reflect overarching political objectives and goals. Hence, strategic plans offer insight into institutional ambitions as well as issues concerning external legitimacy. To explore how systems diversity is affected by the mergers, we compare the mission statements and the strategic plans of the six newly merged institutions with institutions that were not part of these merger processes in the Norwegian higher education system (HiVolda, HiØ, NMBU, OsloMet, UiA, UiB, UiO, UiS). In addition, we analyse the previous institutions missions (HiÅ, HiG, UiT, HiHarstad, HiNT, HBV, HiT, HiB, HSF, HSH) discussing and reflecting upon system diversity and the role mergers are playing in maintaining system diversity.

The empirical backbone of the paper is a thematic document analysis of strategic plans and position papers written by the merged institutions compared with a group of institutions that did not merge at the time (see Appendix). Strategic plans were retrieved from the institutions’ homepages, while the position papers were retrieved from the government’s homepage and by direct communication with the ministry. All documents were read and coded in process of back and forth reading aiming at identifying how the open concepts of excellence and relevance were thematised. Academic excellence was expressed in terms such as the pursuit of knowledge justified, reference to academic freedom and research excellence. Societal relevance was expressed in terms such as relevance to the labour market, students, other external stakeholders or society at large. The analysis explored in an inductive way how the strategies and position papers applied arguments and justifications that could be aligned with either academic excellence or with societal relevance or a combination of the two. The result of the analysis was then contextualised and validated by the two researchers’ in-depth knowledge of the institutions explored and of the development of the higher education sector over time.

Missions and system diversity before the mergers

Most of the institutions before the mergers catered to a large extent for societal relevance. Amongst the former universities, all three of them had, of course, academic ambitions, but looking into the position papers, only one of them—the technologically oriented university NTNU—clearly underlined this ambition. The University of Tromsø stated it was positive towards mergers with institutions in the region. The University of Nordland wanted to merge with university colleges to contribute to the knowledge needs of the region and nationally. The university had a strong regional profile and argued that a merger could strengthen this. In the preparatory phase, NTNU argued that it aimed to further develop programmes and measures to support the best researchers and provide them with the best possible framework conditions and working conditions.

The institutions which later merged consisted of a large group of institutions which catered for the systems’ relevance to the region, labour market and society. For example, Ålesund University College argued that a merger would realise their goals and enable them to emerge as an attractive campus that would meet the needs of business and industry and to meet the requirements that would be set for quality, efficiency and robustness in the future. Gjøvik University College pointed to the academic synergies and opportunities for the university college and the region. The merger would represent a clear reinforcement of the region’s development potential and opportunities for collaboration between regional social and working life. Harstad University College aimed to further develop its professional education for the benefit of its geographical region and the rest of the country. Narvik University College’s objective was to be an attractive campus which meets the needs of working life and industry. The main aim of Nesna University College was to safeguard an independent higher education institution in the region to contribute to regional needs. Nord-Trøndelag University College argued that a potential merger should not affect the distinct profile of the college as a strong regional actor. Buskerud and Vestfold University College’s vision was to develop into a professional and work-oriented university. Telemark University College’s mission was to be an attractive university in Southeast Norway with a clear profession and work-oriented profile characterised by proximity to students and society. Bergen University College wanted to further develop its academic profile, which was professional and work-oriented. Sogn of Fjordane University College aimed to develop further as an independent university college. The institution wanted to safeguard its local autonomy which the university college saw as a prerequisite for realising the regional commitments developed over the years where innovation within the professional fields of the college had high priority. Stord and Haugesund University College’s main goal was to become part of a new and strong professional university in Western Norway.

Yet, a couple of the university colleges had a more academically and excellence oriented strategic profile. Sør-Trøndelag University College argued consistently for merger to strengthen their academic quality and profile, and enable more collaboration with other institutions—nationally and internationally. Hedmark University College aimed at becoming even better at interacting with working and social life and at the same time continue the academic work that would qualify for university level. Lillehammer University College believed that a merger would provide academic synergies, strengthen the quality of research and education, and improve access to competence in the region.

Missions and strategic foci after the mergers

Analysis of the current strategic plans shows interesting changes in the institutional profiles after the mergers. Only two of the newly merged institutions have profiles resembling clearly the strategic profile of the former institutions: this concerns the University of South-East Norway and Vestlandet University College. The university colleges which became University of South-East Norway and the university colleges that formed Vestlandet University College had profiles mainly emphasising relevance.

The four other new institutions changed profile after the merger compared with the profiles of the former institutions. The newly merged NTNU emphasises mainly relevance in the current strategy, although this institution consists of four different institutions, of which two put a strong emphasis on relevance and two having an excellence profile. The newly merged Innlandet University College consists of former institutions emphasising relevance, while the current strategy has its focus on excellence. Both the University of Tromsø and Nord University in their current strategy emphasise both relevance and excellence, while each institution consists of former institutions which have relevance as their main priority. It seems as if the pattern of strategic foci has shifted to a large extent during the mergers; this has deep consequences for the system diversity before and after the mergers.

Three of the new institutions have a strategic profile after the mergers which put emphasis on relevance to the labour market, the region and society in their mission statements. NTNU states that the university develops and disseminates knowledge and manages expertise about nature, people, society and technology. Furthermore, NTNU promotes and disseminates cultural values, and contributes to innovation in society, business and public administration, and uses knowledge to benefit society. NTNU contributes to Norway’s development, creates value—economic, cultural and social—and has a national role in developing the technological foundation for future society. NTNU is an important partner for development in the cities and regions where the university is located. The University of South-East Norway aims to develop into an internationally oriented, regionally based and entrepreneurial university of a high international quality with a strong work community and with society and industry as close collaborative partners. Students at the University of South-East Norway will experience innovative teaching methods and challenging study programmes closely linked to the demands and needs of society. Furthermore, the University of South-East Norway aims for students to learn how to adapt to a society and working life that is in constant change. Vestlandet University College aims to create new knowledge and expertise, anchored internationally and translated into solutions that work locally. Furthermore, Vestlandet University College aims to be a university with a professional and labour-oriented profile.

After the mergers, only one of the new institutions has a clear strategic focus on excellence. Innlandet University College states that the institution is based on what has been the foundation since the nineteenth century for higher education, namely that research and education must mutually enrich each other. Furthermore, the institution underlines that these values include academic freedom, implying that research and education at Innlandet University College should promote independent and critical knowledge.

Two of the merged institutions have a hybrid and mixed strategic profile after the merger. University of Tromsø currently aims to contribute to knowledge-based development at the regional, national and international levels, using its geographic location in the High North as an argument for the need to balance these expectations. The other merged institution in the region, Nord University, is also emphasising the need to balance global challenges and regional embedding.

Strategic profile of other institutions

So far, the analysis has concentrated on changes in strategic profiles before and after the mergers at 15 institutions which formed 6 new institutions as result of mergers in 2016 and 2017. The analysis indicates that a few changes in strategic profiles have taken place. However, to analyse changes in system diversity as result of the ongoing merger processes, we must consider the current strategic profile of the remaining institutions as well. The remaining institutions are 8 institutions, 4 rather new universities, 2 old universities and 2 university colleges.

Amongst these, three institutions focus mainly on relevance in their strategy: one of the new universities and the 2 university colleges. Oslo Metropolitan University—a new university—has as its vision to deliver knowledge to solve society’s problems. The university aims to take a hands-on approach to meeting the needs of society and employers. The university will educate graduates to be engaged citizens who recognise the importance of, and are motivated for, lifelong learning. Volda University College aims to develop a study and academic environment to meet future knowledge and competence needs, regional and national. Østfold University College aims to be a nationally attractive college with regional anchorage. The university college aims to be a forward-looking knowledge actor through an employment-oriented study and professional portfolio focusing on quality, interdisciplinarity and flexibility. The core must be recognised Bachelor’s and Master’s programmes primarily derived from the region’s need for expertise. The university college aims to be a driving force in regional development and an attractive partner for work and social life both regional, national and international.

The group of institutions focusing mainly on excellence consists of two old universities. The University of Bergen states that the university has been, is now and shall continue to be an international research university in which all activity is based on academic freedom and curiosity-driven research. The mission of the university is to contribute to society through expertise acquired through excellent research, education, dissemination of knowledge and innovation. The University of Oslo’s ambition is to develop the university into a first-class international university, where the interaction across research, education, communication and innovation is at its best. One important task will be to come to terms with and clarify current challenges, and to conduct long-term, future-orientated research. The university states that an outstanding research-intensive university must be an active participant in international cooperation on research and education, and the University of Oslo will aspire to making a stronger contribution to this cooperation.

Those institutions focusing both on excellence and relevance consist of three rather new universities. The Norwegian University of Life Sciences aims to educate outstanding candidates, perform high-quality research that produces new perspectives and create innovation. The university will have open and respectful cooperation with the world around, with both the public and private sectors. The institution aims to be an internationally renowned university. The University of Stavanger aims to have an innovative and international profile and to be a driving force in knowledge development and in the process of societal change. The university states that it has a regional, national and global view throughout the academic activities, and staff and students have an international outlook. The university aims to offer future-oriented courses, and critical and independent research of a high international standard, in which ideas transform into value creation for the individual and society. The University of Agder’s vision is co-creation of knowledge. The university wishes to further develop education and research at a high international level. Together with the larger community, the University of Agder aims to develop new methods for internal and external cooperation. The university states that regional, national and global cooperation sets up new perspectives and solutions for the society of the future, and University of Agder is to be a driving force for developing society, culture, and industry and commerce.

Returning to the system level: the strategic profile of newly merged institutions compared with other institutions

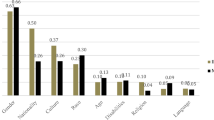

Comparing the profile of other institutions with how newly merged universities and university colleges balance excellence and relevance with the other institutions suggests that Norway currently has a diverse system (see Table 2).

One group of institutions has moved from focusing on relevance to developing a balanced profile (University of Tromsø, Harstad University College, Nord-Trøndelag University College and University of Nordland, Nesna University College). Another group of institutions has moved from emphasising excellence before the merger to emphasising relevance after the merger (NTNU and Sør-Trøndelag University College). And a third group of institutions has moved from a balanced profile to currently maintaining excellence (Hedmark University College and Lillehammer University College).

Thus, from a system diversity perspective, we may currently identify newly merged university colleges (Innlandet University College) emphasising their academic and research mission, newly merged universities and university colleges highlighting their contribution to society and relevance (NTNU, University of South-East Norway, Vestlandet University College) and institutions having a profile which expresses a combination of aspirations directed at excellence and relevance and includes newly merged universities and university colleges (University of Tromsø, Nord University).

Thus, on the level of system diversity, the higher education landscape after the mergers has ‘lost’ a number of institutions which mainly catered for relevance, and ‘gained’ a number of institutions with a balanced profile catering both for relevance and excellence.

It can be argued that newly merged universities and university colleges experience profound organisational transformations challenging the history of previous separate organisations at the same time as new missions are built. Excellence and relevance are mostly thought of as competing objectives that cannot be easily combined. The analysis indicates that most of the newly merged institutions seem to address either excellence or relevance in their new mission statement. Meanwhile, a third group of institutions containing mergers of universities and university colleges exhibit a joint effort to achieve both.

Concluding remarks

In this article, we have analysed organisational missions to understand how merger processes may affect system diversity. Using relevance and excellence as indicators for analysing the missions developed, we have found that the merged institutions ended up with quite mixed missions following the merger process. Three of the merged institutions ended up with mission statements clearly emphasising relevance, one institution ended up with a clear emphasis on excellence, while two institutions ended up with trying to balance relevance and excellence in their mission statement. Kyvik (2009) has argued that in many countries one could find a tendency of institutional drift where former colleges have transformed into universities, and that this shift in institutional status also will affect their previous focus on relevance (teaching orientation) in favour of academic excellence (research orientation). In our study, we find that one merged university college indeed has ended up with having a strong orientation to excellence, and that two previous universities which historically had an orientation towards relevance are now emphasising a combination. However, two merged institutions have maintained a focus on relevance in their strategic plans and mission statements suggesting that (at least so far) they have remained true to their historical legacy. One institution has changed its mission from trying to balance relevance and excellence, to ending up with emphasising relevance.

These complex outcomes reflect the need for multiple theoretical perspectives and explanations. As expected in the instrumental perspective, we can find examples of mergers where existing characteristics and strengths (relevance) also seem to have influenced the new missions (University of South-East Norway, Vestlandet University College) which are clear examples of this expectation. According to the institutional perspective, we expected that new missions would reflect external demands, and those institutions that currently combine relevance and excellence (University of Tromsø, Nord University) are indeed examples of such adjustments. However, the latter broadening of their mission could also be interpreted as a development more in line with what the hybrid perspective expected—towards building a more overarching mission.

However, some institutions are harder to fit into the theoretical perspectives offered. The fact that Innlandet University College shifted focus from relevance to excellence, only reflecting parts of the political expectations (excellence), while paying less attention to others (relevance) was not anticipated. That NTNU shifted focus from balancing relevance and excellence to ending up with a strong focus on relevance is also surprising. These shifts are not easily explained either by the instrumental or by the institutional perspective, and while the missions are new, they are not overarching as suggested in the hybrid perspective. However, these findings may indicate the need to develop the hybrid perspective further as it certainly indicates that merger processes can be quite dynamic and deliver unexpected outcomes. Theoretically, these unexpected findings may also suggest that the distinction between instrumental and the institutional perspectives perhaps should be toned down, and that we need to extend our conceptualisations of organisational dynamics (Stensaker, 2015). Whether and how multiple organisational missions (De Bernardis & Giustiniano, 2015) may co-exist over time, how historical characteristics may be overturned into mission statements that are transformative (Balmer & Burghausen, 2015; Iannone & Izzo, 2017) are also interesting issues to pursue further. Of course, a fundamental issue to research is also how the newly formed missions are ultimately perceived by staff and external stakeholders, and whether the missions developed is seen as legitimate and a source for identification (Gertsen & Zolner, 2014). However, these kinds of studies would require a different set of data and a different methodological approach from the current study. The fact that we observe quite mixed mission statements coming out of the merger processes indicates that we need to better understand the many mediating factors that may have affected these outcomes (Battilana & Lee, 2014).

Our findings stem from an in-depth analysis of Norwegian cases, which of course contain particularities as reported upon in our analysis. Cultural characteristics related to Nordic countries, including a long-standing focus on equality in the region, may shed some light on why an institutional perspective emphasising excellence played a less dominant role. Yet we would argue that the Norwegian case is not unique. While many merger processes around the world indeed are motivated by ‘world class’ ambitions (Välimaa et al., 2014), the emphasis on excellence is far from the only arguments driving mergers. Thus, the universality of our study is related to a better understanding of the potential outcome when merger processes are framed by competing policy objectives such as improved quality, efficiency and relevance.

For policymakers, our results are interesting in that they suggest that mergers may not negatively affect system diversity. If we compare the merged institutions with the mission statements of non-merged institutions in Norway (see Table 2), we could argue that the categories are quite similar, having a spread between institutions focusing on either relevance or excellence or a balance between them. Interestingly, we find institutions having the status of a university or of a university college in all categories, except for those aiming to balance relevance and excellence. Whether this latter category—where several institutions now seem to position themselves (cf. Table 2)—may represent potential long-term institutional drift (Kyvik, 2009) is too early to say, and given the policy objectives behind the structural reform in Norway, one could also argue that the potential drift observed is indeed a drift that has political support.

However, mapping organisational mission statements for the whole educational system should have interest for policymakers, as such regular mapping provides insights into the overarching division of labour between institutions in the system. For policymakers having the ambition to steer the higher education system in a more active way, analysis such as the one conducted may also yield indications of how the overall balancing of system diversity is developing over time.

References

Balmer, J. M. T., & Burghausen, M. (2015). Introducing organisational heritage: Linking corporate heritage, organisational identity and organisational memory. Journal of Brand Management, 22(5), 385–411.

Battilana, J., & Lee, M. (2014). Advancing research on hybrid organizing - insights from the study of social enterprises. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 397–441.

Bennett, K., Verwey, A., & van der Merwe, L. (2016). Exploring the notion of a ‘capability for uncertainty’ and the implications for leader development. Sa Journal of Industrial Psychology, 42(1).

Bleiklie, I., Enders, J., & Lepori, B. (2015). Organizations as penetrated hierarchies. Environmental presures and control in professional organizations. Organization Studies.

Cai, Y., Pinheiro, R., Geschwind, L., & Aarrevaara, T. (2016). Towards a novel conceptual framework for understanding mergers in higher education. European Journal of Higher Education, 6(1), 7–24.

Clark, B. R. (1983). The higher education system: academic organization in cross-national perspective. University of California Press.

De Bernardis, L., & Giustiniano, L. (2015). Evolution of multiple organisational identities after an M&A event a case study from Europe. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(3), 333–355.

De Boer, H., File, J., Huisman, J., Seeber, M., Vukasovic, M., & Westerheijden, D. F. (Eds.). (2017). Policy analysis of structural reform in European Higher Education: processes and outcomes. Palgrave Macmillan.

Foster, W. M., Coraiola, D. M., Suddaby, R., Kroezen, J., & Chandler, D. (2017). The strategic use of historical narratives: a theoretical framework. Business History, 59(8), 1176–1200.

Frølich, N., Trondal, J., Caspersen, J., & Reymert, I. (2016). Managing mergers - governancing institutional integration. TEAM, 22(3).

Gertsen, M. C., & Zolner, M. (2014). Being a ‘modern Indian’ in an offshore centre in Bangalore: cross-cultural contextualisation of organisational identification. European Journal of International Management, 8(2), 179–204.

Glynn, M. A. (2008). Beyond constraint: how institutions enable identities. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism.

Harman, G., & Harman, K. (2003). Institutional mergers in higher education: lessons from international experience. Tertiary Education and Management, 9(1), 29–44.

Huisman, J. (1995) Differentiation, diversity and dependency in higher education. Dr.thesis, Enschede: University of Twente

Huisman, J., & Van Vught, F. A. (2009). Diversity in European higher education: historical trends and current policies. In F. A. Van Vught (Ed.), Mapping the higher education landscape Towards a European Classification of Higher Education. Springer.

Huisman, J., Lepori, B., Seeber, M., Frølich, N., & Scordato, L. (2015). Measuring institutional diversity across higher education systems. Research Evaluation, 24(4), 369–379.

Iannone, F., & Izzo, F. (2017). Salvatore Ferragamo: an Italian heritage brand and its museum. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 13(2), 163–175.

Johnes, J., & Tsionas, M. G. (2019). Dynamics of inefficiency and merger in English Higher Education From 1996/97 to 2008/9: A Comparison of Pre-Merging, Post-Merging and Non-Merging Universities Using Bayesian Methods. Manchester School, 87(3), 297–323.

Krücken, G., & Meier, F. (2006). Turning the university into an organizational actor. Globalization and organization: World society and organizational change, 241–257.

Kunnskapsdepartementet. (2014–2015). “Meld. St. 18 (2014–2015) Melding til Stortinget. Konsentrasjon for kvalitet. Strukturreform i universitets- og høgskolesektoren”

Kyvik, S. (2004). Structural changes in higher education systems in Western Europe. Higher Education in Europe, XXIX(3), 394–409.

Kyvik, S. (2009). Higher education dynamics. Springer.

Kyvik, S., & Stensaker, B. (2013). Factors affecting the decision to merge: the case of strategic mergers in Norwegian higher education. Tertiary Education and Management, 19(4), 323.

Liu, Q., Patton, D., & Kenney, M. (2018). Do university mergers create academic synergy? Evidence from China and the Nordic Countries. Research Policy, 47(1), 98–107.

Locke, W. (2007). Higher education mergers: integrating organisational cultures and developing appropriate management styles. Higher Education Quarterly, 61(1), 83–102.

Morphew, C., & Hartley, M. (2006). Mission statements: a thematic analysis of rhetoric across international type. Journal of Higher Education, 77(3), 456–471.

Morphew, C. C., Fumasoli, T., & Stensaker, B. (2018). Changing missions? How the strategic plans of research-intensive universities in Northern Europe and North America balance competing identities. Studies in Higher Education, 43(6), 1074–1088.

Norgård, & Skodvin. (2002). The importance of geography and culture in mergers: a Norwegian institutional case study. Higher Education, 44, 73–90.

Paradeise, C., Reale, E., Bleiklie, I., & Ferlie, E. (2009). University Governance. Western European Comparative Perspectives. Dordrecht.

Parsons, T., & Platt, G. M. (1973). The American university. Harvard University Press.

Pritchard, R. M. O., & Williamson, A. (2008). Long-term human outcomes of a ‘shotgun’ marriage in higher education. Higher Education Management and Policy, 20(1), 1–23.

Ramirez, F. (2010). Accounting for excellence: transforming universities into organizational actors. In V. Rust, L. Portnoi, & S. Bagely (Eds.), Higher education, policy, and the global competition phenomenon. Palgrave Macmillan.

Seeber, M., Berberio, V., Huisman, J., & Mampaey, J. (2019). Factors affecting the content of universities’ mission statements: an analysis of the United Kingdom higher education system. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 230–244.

Skelcher, C., & Smith, S. R. (2015). Theorizing hybridity: institutional logics, complex organizations, and actor identities: the case of nonprofits. Public Admin, 93, 433–448.

Skodvin, O. J. (1999). Mergers in higher education – success or failure? Tertiary Education Management, 5(1), 65–80.

Stensaker, B. (2015). Organizational identity as a concept for understanding university dynamics. Higher Education, 69(1), 103–115.

Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (2008). Institutional logics. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism (pp. 1–46). Sage Publications.

Thornton, & Occasio. (1999). Institutional logics and the historical contingency of power in organizations: executive succession in the higher education publishing industry, 1958–1990. American Journal of Sociology, 105(3), 801–843.

Välimaa, J., Aittola, H., & Ursin, J. (2014). University mergers in Finland: mediating global competition. New Directions for Higher Education, 2014(168), 41–53.

van Vught, F. A. (2009). Mapping the higher education landscape: towards a European Classification of Higher Education. Springer.

Wollscheid, S., & Røsdal, T. (work in progress)(n.d.). The impact of mergers in higher education on micro level processes – a literature review. submitted for review in Tertiary Education and Management.

Documents

HBV. (2014). Innspill til arbeidet med framtidig struktur i Universitets- og høgskolesektoren. https://www.regjeringen.no/nb/tema/utdanning/hoyere-utdanning/innsikt/struktur-i-hoyere-utdanning/Innspill/id2008761/: HBV

HiÅ. (2014). SAKS -Innspill til framtidig struktur i UH-sektoren. https://www.regjeringen.no/nb/tema/utdanning/hoyere-utdanning/innsikt/struktur-i-hoyere-utdanning/Innspill/id2008761/: HiÅ.

HiB. (2014). Innspill fra Høgskolen i Bergen til arbeidet med fremtidig struktur i universitets- og høgskolesektoren

HiG. (2014). Innspill fra Høgskolen i Gjøvik til til arbeidet med framtidig struktur i universitets- og høyskolesektoren. https://www.regjeringen.no/nb/tema/utdanning/hoyere-utdanning/innsikt/struktur-i-hoyere-utdanning/Innspill/id2008761/: HiG

HiHarstad. (2014). Høgskolen i HArstad sitt innspill til arbeidet med framtidig struktur i universitetets- og høyskolesektoren samt plan for dialogmøtene. https://www.regjeringen.no/nb/tema/utdanning/hoyere-utdanning/innsikt/struktur-i-hoyere-utdanning/Innspill/id2008761/: HiHarstad.

HiHe. (2014). Innspill fra Høgskolen i Hedmark til arbeidet med framtidig struktur i universitets- og høgskolesektoren

HiL. (2014). Innspill til arbeidet med framtidig struktur i universitets- og høgskolesektoren

HiNarvik. (2014a). Innspill fra Høgskolen i Narvik til arbeidet med framtidig struktur i universitets- og høgskolesektoren.

HiNarvik. (2014b). Styret ved Høgskolen i Narvik hadde følgende sak til behandling den 10. desember 2014 og rektor Arne Erik Holdø ønsker å videreformidle dette resultatet for deres orientering. https://www.regjeringen.no/nb/tema/utdanning/hoyere-utdanning/innsikt/struktur-i-hoyere-utdanning/Innspill/id2008761/: HiNarvik.

HiNesna. (2014). Høgskolen i Nesnas inn spill til arbeidet med framtidig struktur i UH-sektoren. https://www.regjeringen.no/nb/tema/utdanning/hoyere-utdanning/innsikt/struktur-i-hoyere-utdanning/Innspill/id2008761/: HiNesna.

HiNT. (2014). HiNTs strategiske posisjon i 2020

HiØ. (2019). Strategic plan 2019-2022. . https://www.hiof.no/english/about/strategy/.

HiST. (2014). Innspill til arbeidet med framtidig struktur i universitets- og høyskolesektoren. https://www.regjeringen.no/nb/tema/utdanning/hoyere-utdanning/innsikt/struktur-i-hoyere-utdanning/Innspill/id2008761/: HiST.

HiStord/Haugesund. (2014). Innspill fra Høgskolen i Stord/Haugesund til arbeidet med framtidig struktur i universitets- og høyskolesektoren. https://www.regjeringen.no/nb/tema/utdanning/hoyere-utdanning/innsikt/struktur-i-hoyere-utdanning/Innspill/id2008761/: HiStord/Haugesund.

HiT. (2014). Høgskolen i Telemark sitt strategiske innspill ti lKunnskapsdepartemente (KD) i forbindelse med strukturendring i sektoren.

HiVolda. (2017). Strategiplan for Høgskulen i Volda 2017-2020. https://www.hivolda.no/sites/default/files/documents/Strategiplan%20for%20H%C3%B8gskulen%20i%20Volda%202017%202020_revidert%2008.03.2018.pdf.

HSF. (2014). Innspel frå Høgskulen i Sogn og Fjordane til strukturmeldinga til Kunnskapsdepartementet, 31.10.14

HSH. (2014). INNSPILL FRA HØGSKOLEN STORD/HAUGESUND TIL ARBEIDET MED FRAMTIDIG STRUKTUR I UNIVERSITETS- OG HØYSKOLESEKTOREN

HVL. (2019). Interaction. Sustainability. Innovation. Strategy 2019-2023 Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. https://www.hvl.no/globalassets/hvl-internett/dokument/strategi-og-plan/hvl-strategy2023_eng.pdf.

INN. (2018). Sterkere sammen. Strategi for 2018 - 2020. file:///C:/Users/py52/Downloads/H%C3%98IN0017_Strategi+2018-2020_web.pdf.

NMBU. (2019). NMBUs strategi 2019 til 2023. https://www.nmbu.no/om/strategi/2019-2023#innledning.

Nord. Nord Universitet. Strategi 2020. https://www.nord.no/no/aktuelt/nyheter/Documents/Nord%20universitet%20_%20Strategi%202020.pdf.

NTNU. (2014). Oppdrag til statlige institusjoner: Innspill til arbeidet med framtidig struktur i universitets- og høyskolesektoren. https://www.regjeringen.no/nb/tema/utdanning/hoyere-utdanning/innsikt/struktur-i-hoyere-utdanning/Innspill/id2008761/: NTNU.

NTNU. (2015). Vedrørende innspill til strukturmeldingen - KD ber styret ved NTNU om å vurdere alternativet flercampusmodell på linje med de to andre alternativene. https://www.regjeringen.no/nb/tema/utdanning/hoyere-utdanning/innsikt/struktur-i-hoyere-utdanning/Innspill/id2008761/: NTNU.

NTNU. (2018). Strategy 2018-2025. Konwledge for a better world. https://www.ntnu.no/documents/1277297667/1278198595/20180228_NTNU_strategi_web_ENG.pdf/cb19eb5b-bd82-453d-ac54-8e89c67509e3.

OsloMet. (2017). Strategi 2024. Ny viten - ny praksis. https://ansatt.oslomet.no/documents/585743/66116386/Strategi+2024_norsk2.pdf/57ad0d99-8cf7-a0fd-75ad-6d1eda2e7127.

UiA. (2016). Strategy 2016 - 2020. https://www.uia.no/en/about-uia/organisation/strategy-2016-2020.

UiB. (2019). Knowledge that shapes society. OCEAN, LIFE, SOCIETY STRATEGY 2019–2022 http://ekstern.filer.uib.no/ledelse/strategy.pdf.

UiN. (2014). Oppdrag til statlige høyere utdanningsinstitusjoner: Innspill fra Universitetet i Nordland til arbeidet med framtidig struktur i universitetets- og høyskolesektoren.

UiO. Strategy 2020. UiO. University of Oslo. https://www.uio.no/english/about/strategy/Strategy2020-English.pdf.

UiS. (2017). Strategy for the University of Stavanger 2017-2020. https://www.uis.no/getfile.php/13419590/Ansattsider/Grafisk%20profil/EN_Strategi%20for%20UiS%202017-2020-1.pdf.

UiT. (2014a). Innspill til arbeidet med framtidige strukturer i høyere utdanning. https://www.regjeringen.no/nb/tema/utdanning/hoyere-utdanning/innsikt/struktur-i-hoyere-utdanning/Innspill/id2008761/: UiT.

UiT. (2014b). Strategic plan for UiT The Arctic University of Norway 2014-2022. https://en.uit.no/utskrift?p_document_id=377752.

USN. (2017). USN Strategy 2017-2021. https://www.usn.no/getfile.php/13505990-1567582065/usn.no/en/About%20USN/Strategies/USN%20strategy%202017%20-%202021.pdf

Funding

The paper is part of the research-based evaluation of the Structural Reform, funded by the Research Council of Norway, grant number ES645248.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Approach and method

Empirically, the idea of this paper is to compare strategic plans and mission statements formulated by newly merged higher education institutions in order to explore how excellence and relevance is articulated. The comparison is done in two ways. First, the newly merged institutions’ mission statements are compared with a group of institutions less affected by mergers. Then, the strategic plans and mission statements of the newly merged institutions are compared with strategic plans the former institutions becoming part of the merged institutions.

The empirical backbone of the comparisons consist of the current strategic plans of 9 Norwegian universities and 5 university colleges (HiØ, 2019; HiVolda, 2017; HVL, 2019; INN, 2018; NMBU, 2019; Nord, 2020; NTNU, 2018; OsloMet, 2017; UiA, 2016; UiB, 2019; UiO, 2020; UiS, 2017; UiT, 2014b; USN, 2017) and the former institutions position papers produced as part of the merger process (HBV, 2014; HiÅ, 2014; HiB, 2014; HiG, 2014; HiHarstad, 2014; HiHe, 2014; HiL, 2014; HiNarvik, 2014a; HiNesna, 2014; HiST, 2014; HiStord/Haugesund, 2014; HiT, 2014; HSF, 2014; HSH, 2014; NTNU, 2014; NTNU, 2015; UiN, 2014; UiT, 2014a). The current 14 mission statements were mapped in three categories: institutions which focus mainly on relevance, those which focus mainly on excellence and those focusing on a combination of relevance and excellence. The same mapping was done with the former institutions’ position papers.

Analysis of current strategies

Strategic focus on relevance

The group of institutions which focus mostly on their contribution to relevant higher education consists of three newly merged institution and three other institutions. Both the newly merged group and the other group include universities and university colleges. The technology-oriented university NTNU (2018) states that the university develops and disseminates knowledge and manages expertise about nature, people, society and technology. Furthermore, NTNU promotes and disseminates cultural values, and contributes to innovation in society, business and public administration and use knowledge to benefit society. NTNU contribute to Norway’s development, create value—economic, cultural and social—and have a national role in developing the technological foundation for the future society. NTNU is an important partner for development in the cities and regions where the university located.

USN (2017), a new university consisting of a merger between two previous university colleges, aims to develop into an internationally oriented, regionally based and entrepreneurial university of a high international quality with a strong work community and with society and industry as close collaborative partners. Students at USN will experience innovative teaching methods and challenging study programmes closely linked to the demands and needs of society. Furthermore, USN aims at students to learn how to adapt to a society and working life that is in constant change.

HVL (2019) which is a newly merged institution consisting of three previous university colleges aims to create new knowledge and expertise, anchored internationally and translated into solutions that work locally. Furthermore, HLV aims to be a university with a professional and labour-oriented profile.

Three other institutions focus mainly on relevance as well. OsloMet (2017)—a new university—has as its vison to deliver knowledge to solve society’s problems. The new university aims to take a hands-on approach to meeting the needs of society and employers. The university will educate the graduates to be engaged citizens who recognise the importance of, and are motivated for, lifelong learning.

HiVolda (2017) aims to develop a study and academic environment to meet future knowledge and competence needs, regional and national.

HiØ (2019) aims to be a nationally attractive college with regional anchorage. The university college aims to be a forward-looking knowledge actor through an employment-oriented study and professional portfolio focusing on quality, interdisciplinarity and flexibility. The core must be recognised bachelor and master’s programmes primarily derived from the region’s need for expertise. The university college aims to be a driving force in regional development and an attractive one partner for work and social life both regional, national and international.

Strategic focus mainly on excellence

Three institutions, two old universities and a newly merged institution consisting of two previous university colleges emphasise mainly the excellence contribution to higher education. UiB (2019) states that the university has been, is now and shall continue to be an international research university in which all activity is based on academic freedom and curiosity-driven research. The mission of the university is to contribute to society through expertise acquired through excellent research, education, dissemination of knowledge and innovation.

UiO’s (UiO) ambition is to develop the university into a first-class international university, where the interaction across research, education, communication and innovation is at its best. One important task will be to come to terms with and clarify current challenges, and to conduct long-term, future-orientated research. The university states that an outstanding research-intensive university must be an active participant in international cooperation on research and education, and UiO will aspire to making a stronger contribution to this cooperation.

INN (2018)—which consists of a merger between two previous university colleges—states that the institution is based on what has been the foundation since the nineteenth century for higher education, namely that research and education must mutually enrich each other. Furthermore, the institution underline that these values include academic freedom, implying that research and education at INN should promote independent and critical knowledge.

Strategic focus on relevance and excellence

Those institutions focusing both on excellence and on relevance consist of two newly merged institutions, on institutions consisting of an old university merging with several university colleges and a new university consisting of several university colleges.

UiT (2014b) aims at contributing to knowledge-based development at the regional, national and international level. The university states that the central location in the High North, its broad and diverse research and study portfolio, the geographical breadth and interdisciplinary qualities make the university uniquely suited to meet the challenges of the future.

Nord University’s (Nord) vision is global challenges—regional solutions. The university states that good regional solutions are the basis for meeting global challenges. Furthermore, this requires regional, national and international research collaboration across subjects. Through research and research-based education, and through dissemination of new knowledge, Nord University aims to contribute with knowledge to support sustainability as well as social and human development.

NMBU (2019) aims to educate outstanding candidates, perform high-quality research that produces new perspectives and create innovation. The university will have open and respectful cooperation with the world around, with both the public and private sectors. NMBU aims to be an internationally renowned university.

UiS (2017) aims to have an innovative and international profile and to be a driving force in knowledge development and in the process of societal change. The university states that it has a regional, national and global view throughout the academic activities, and staff and students have an international outlook. The university aims to offer future-oriented courses, and critical and independent research of a high international standard, in which ideas transform into value creation for the individual and society.

UiA’s (2016) vision is co-creation of knowledge. The university wishes to further develop education and research at a high international level. Together with the larger community, UiA aims to develop new methods for internal and external cooperation. The university states that regional, national and global cooperation set up new perspectives and solutions for the society of the future, and UiA is to be a driving force for developing society, culture, and industry and commerce.

Analysis of how newly merged universities and university colleges balance two conflicting objectives, excellence and relevance, in their mission statements provide three mission profiles (Table 3).

The first mission profile includes newly merged university colleges (INN) emphasising their academic and research mission. The second mission profile includes newly merged universities and university colleges highlighting their contribution to society and relevance (NTNU, USN, HVL). The third mission profile expresses a combination of aspirations directed at excellence and relevance and includes newly merged universities and university colleges (UiT, Nord). It can be argued that newly merged universities and university colleges experience profound organisational transformations challenging the identity of previous separate organisations while at the same time new identities are built. Excellence and relevance are mostly thought of as competing objectives that cannot be easily combined. The analysis indicates that most of the newly merged institutions seem to address either excellence or relevance in their new mission statement, while a third group of institutions containing mergers of universities and university colleges exhibit a joint effort to achieve both.

Analysis of previous position papers

The newly merged institution NTNU was established by a merger between NTNU, HiST, HiÅ and HiG. In the preparatory phase, NTNU (2014) suggested to merge with HiST, HiÅ and HiG and argued that NTNU’s main approach would be multidisciplinary and multidisciplinary. At the same time, the university would further develop programmes and measures to support the best researchers and provide them with the best possible framework conditions and working conditions. Regarding education, the aim was to offer attractive and research-based study programmes.

HiST (2014) argued for a merger with NTNU and another university college, HiNT, which did not become a part of this merger, pointing at the institutions’ complementary academic environments. The argument was that complementary academic environments could trigger a number of academic disciplines as well as synergy effects related to teaching, research and innovation. Moreover, HiST argued that such a merger would in a Norwegian context have a particularly useful portfolio of educational programmes and in student numbers become one of the largest educational institutions in Norway. A third argument was about research environments. HiST argued that complementary and related academic environments would be brought together, which would provide opportunities for collaboration that would increase interdisciplinarity and increase the ability of the environments to realise their academic potential.

HiÅ’s (2014) board concluded that a merger was necessary in order for HiÅ to realise its goals, and to emerge as an attractive campus that would meet the needs of business and industry and to meet the requirements that will be set for quality, efficiency and robustness in the future. The board wanted the following non-prioritised alternatives to be further explored and concretised: Merger with NTNU based on a satellite model; Merger with Molde University College, Volda University College and Sogn and Fjordane University College.

HiG’s (2014) board’s conclusion was that a merger with NTNU as a key player would best support the university college’s vision and ambition. The board pointed at the academic synergies and opportunities for the university college and the inland region. A merger with NTNU would be the best framework for furthering the initiatives HiG had. Such a merger would represent a clear reinforcement of the region’s development potential and opportunities for collaboration between Campus Gjøvik, regional social and working life and the University College of Lillehammer. The merger would provide a strong brand in relation to national and international education, recruitment, research, innovation and social contact. Because Campus Gjøvik could utilise existing PhD programmes at NTNU, this would allow for complete educational courses within all HiG’s academic pillars (provided that supervisor expertise is available locally), without the establishment of a new PhD programme.

USN was formed by a merger between two university colleges, HBV and HiT. HBV’s (HBV, 2014) vision was to develop into a professional and work-oriented university. Within a national structure based on regionally based institutions, HBV saw a merger with HiT as the most relevant alternative at the time. However, if the government chooses a national model where it would be opened up for national multi-campus institutions, HBW would consider that a merger with HiT would be less relevant. HBV would then want instead to become part of such a structure.

HiT’s (2014) vision was to be an attractive university in Southeast Norway with a clear profession and work-oriented profile characterised by proximity to students and the society. HiT’s aim was to be the preferred competence, research, development and innovation partner for regional social and business life. At the same time, HiT aimed to be amongst the country’s leaders in priority areas and be internationally oriented. HiT argued that a national structure based on regionally established institutions would best meet the ambitions that the government had signalled for higher education and research. Based on this, HiT saw a merger with Buskerud University College and Vestfold (HBV) as the most relevant alternative at this time.

HVL was formed by a merger between three university colleges, HiB, HSF and HSH. HiB (2014) wanted to further develop its academic profile, which was professional and work-oriented. The long-term goal was to become a professional university in Western Norway. The board saw two alternative ways to realise this, either merger between university colleges in Western Norway with the aim of establishing a professional university, with HSH, HiSF and HiVo as relevant merger partners, or merger between HiB and UiB. HiB argued that such a merger might also include other university colleges in the region.

HSF’s (2014) position was that the university college develops further as an independent university college. HSF wanted to safeguard its local autonomy which the university college saw as a prerequisite for realising the desired strategic profile. HSF aimed at a profile of high academic quality with attractive study centres located in small-scale communities, where the university college would further develop its expertise and utilise the favourable conditions the institution saw it had for creating engaging and stimulating research and learning environment. The aim was to develop research-based knowledge and innovation within the professional fields HSF had based on geographical location, expertise and regional community and working life.

HSH’s (2014) main goal in the future university and college landscape was to become part of a new and strong professional university in Western Norway and suggested a merger with UiS. UiS and HSH are geographically close to each other, which will be strengthened when Rogfast (a new road including the world longest below sea tunnel) is completed. There was a great degree of academic similarity and complementarity that made HSH wanting to accept UiS’s invitation about discussing merger. The educational programme and R&D project at Stord/Haugesund University College are the result of the knowledge, the skills and skills’ needs of the regional working life and have similarities to the University of Stavanger’s portfolio and profile.

INN became a new university college as a result of a merger between HiHe and HiL. HiHe (2014) aimed at being even better at interacting with working and social life and at the same time continue the academic work that can eventually qualify for university level. HiHe had a common goal of qualifying for university status with HiG and HiL. HiHe’s university vision was high ambitions about research-based educations, two robust research educations and nationally and internationally collaboration to promote high quality in all our disciplines as well as a goal to succeed compete for national and international research funding. HiHe was committed to being innovative and respond to the workforce’s need for expertise and new insights while they gradually and purposeful worked to qualify the institution for a university level. In order to succeed with the academic ambitions and the desired strategic profile, the university college foresaw to strengthen the ongoing internal quality work with education and research. First and foremost, HiHe wanted to develop and strengthen more committed cooperation with others—both higher educational institutions and working and community life. Such cooperation should promote high quality in education and research, but also contribute to profiling and division of labour within various disciplines and to strengthen work-life relevance and work-life attachment.

HiL (2014) believed that a merger between HiL and HiG provided academic synergies, strengthen the quality of research and education and improve access to competence in the region. In the case that a merger with HiG would not be realised, the board of HiL believed that the institution should be further developed within the current institutional framework. If a merger with HiG should not be applicable, HiL would be able to stand strong alone, given their position as national flagship in film and television, with strong professional environments and high competence profile, continuous study and good quality as well as good recruitment and good throughput.

UiT was established as a merger between UiT, HiHarstad and HiNarvik. UiT (2014a) stated they were positive to mergers with institutions in the region, mentioning HiNesna, HiHarstad and HiNarvik.

HiHarstad (2014) wanted to further develop its professional education for the benefit of its own region, Northern Norway and the rest of the country. HiHarstad had long been a driving force for the development of decentralised educational programmes. Furthermore, by opening up more actors, students in Harstad were given a greater scope of study choices than would otherwise be possible. The university college foresaw an orientation north towards UiT Norway’s Arctic University or south towards the University of Nordland. In both alternatives, HiHarstad saw it as a clear advantage that the HiNarvik went the same way. The board had assessed the various alternatives against each other and concluded that several factors spoke in favour of merging with UiT.

HiNarvik, 2014a, b main priority was the establishment of a university of the region. Since the ministry did not want such a university, the priority of HiNarvik was to remain independent. The objective of HiNarvik was to be an attractive campus which meet the need of the working life and industry. The second alternative is to merge with NTNU, UiT or the University in Nordland.

Nord University was established as a merger between University of Nordland, HiNesna and HiNT. University of Nordland (UiN, 2014) wanted to merge with HiHarstad, HiNarvik and HiNesna to contribute to the knowledge needs of the region and nationally.

HiNesna (2014) wanted to remain independent. Alternatively, HiNesna wanted to merge with UiN. HiNesna’s main aim was to safeguard an independent higher education institution in the region to contribute to regional needs.

HiNT (HiNT, 2014) argued that three different options would strengthen the institution’s role as a regional actor. First, as an independent institution, HiNT would be able to fulfil the social mission in a good way. However, in order to accommodate future and reported changes in teacher education, HiNT had to implement measures to ensure that HiNT could serve this purpose. Second, a merger with HiST would open for a larger and stronger academic environment in several of the educational programmes. Third, a merger with UiN. As a university, UiN has a strong regional profile. Thus, a merger could strengthen both institutions.

The analysis of the position papers indicate that most former institutions put main emphasis on relevance, two former institutions emphasis mainly excellence and two former institutions both excellence and relevance (Table 4).

Yet only two of the newly merged institutions consist of former institutions that all had as main strategy to focus on the same type of objective that the merged institution does (Table 5). This regards USN and HVL, all these former institutions had as their profile to put main emphasis on relevance. The newly merged NTNU emphasises mainly relevance in the current strategy, while the institution consists of former institutions out of which two had relevance as the main emphasis and two excellence. The newly merged INN consists of former institutions emphasising relevance, while the current strategy has its main focus on excellence. Both Tromsø and Nord in their current strategy emphasises both relevance and excellence, while both institutions consist of former institutions which has relevance as their main priority.

Main focus on relevance | Main focus on excellence | A combined focus on relevance and excellence | |

|---|---|---|---|