Abstract

The Global North has over the years been a popular destination for migrants from the Global South. Most of the migrants are in their reproductive ages who go on to bear and raise children. The differences and subjectivity in the context of their experiences may have an impact on how they ensure that their children have the best possible health and well-being. This paper synthesises 14 qualitative research papers, conducted in 6 Global North countries. We gathered evidence on settled Southern African migrants experiences of bearing and raising children in Global North destination countries and how they conceptualise sustaining children’s health and well-being. Results of the review indicated a concerning need for support in sustaining children’s health and well-being. Cultural and religious beliefs underpin how the parents in these studies raise their children. More research is needed which engages with fathers and extended family.

Highlights

-

Fathers and extended family should be included in parenting research.

-

There is a need to expand work in investigating these groups separately and understand the nuances between them.

-

These findings can be used to support the voice of settled migrants in the evidence base.

Similar content being viewed by others

Parenting among Settled Migrants from Southern Africa: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

Since 1970, the world has seen increasingly large flows of migrants from the Global South to the Global North for better living conditions (Adserà & Tienda, 2012). The phrase Global South tends to be broadly used to refer to regions of Africa, Latin America, and developing Asia, including the Middle East. The term Global North encompasses regions of North America, Western Europe, and developed parts of East Asia (Confraria et al., 2017). Contemporary international migration has received considerable critical attention because it presents new challenges in sustaining health and well-being. All cultures aim for good children’s health and well-being, however, immigrant parents often seek a culture balance in destination countries to ensure that their children assimilate into the destination society and preserve some of their culture (Nesteruk & Marks, 2011). The term ‘migrant’ is defined by the United Nations (2019, n.p) as ‘someone who changes his or her country of usual residence, irrespective of the reason for migration or legal status’. Thus, they represent a highly heterogeneous population which may have different constructions of health. It is important to note that the experiences associated with migration vary as parents use different routes and sometimes include more opportunity to physical, economic and political security (Altschuler, 2013). Furthermore, almost half of all migrants are women, and most of the migrating population are of reproductive age; hence, many children are born to migrant parents (United Nations Population Fund, 2019). This gives rise to research on their welfare in the destination countries to ensure their life chances are not based on foundational inequalities.

Settlement is commonly linked to negotiation of social capital means, such as employment, often surrounded by perceived racism and discrimination, cultural adaptation, and integration factors (Alemi & Stempel, 2018; Nannestad et al., 2013; Renzaho et al., 2011; Vathi, 2015). The differences and subjectivity in the context of their experiences may have an impact on how they ensure that their children have the best possible health outcomes. Several studies suggest that migrants’ health deteriorates over time from their point of entry into a destination country (Fernández-Reino, 2020). It is still unclear whether the deterioration is due to acculturation (adoption of norms, values, and lifestyles prevalent in the destination country) or structural barriers to good health (socio-economic deprivation and poor access to services) (Condon & McClean, 2017). Children represent a vulnerable group as they mirror their parents’ health behaviours as a foundation for their lifelong health path. Deteriorating health behaviours among migrant parents predispose both adults and children to ‘lifestyle-related’ diseases (Condon & McClean, 2017). This indicates a need to understand the foundations for promoting children’s health as they represent a diverse and growing group.

Understanding migrant parents’ experiences may provide some ideas about how they sustain their children’s health and well-being. Since migrants constitute a highly heterogeneous population, the focus of this qualitative synthesis is on migrants from Southern Africa, a region in the Global South, who moved to a Global North destination country. It should be noted here that the Global North, for the purposes of this paper, consists of the countries of Western Europe, North America, and Australia and New Zealand which represent a common destination for a great number and growing population (Eten, 2017). This review gathers contemporary qualitative evidence on settled Southern African migrants’ experiences of bearing and raising children in Global North destination countries and collates qualitative evidence on how they conceptualise sustaining children’s health and well-being in these destination countries. Our use of the term Southern Africa is not meant to homogenise but to draw out common experiences while recognising the diversity within these. To date, no reviews synthesising qualitative research on this body of literature have been identified. This study aims to explore if there is a gap on migrant parenting and maintaining children’s health and well-being, as well as informing process and methodology for subsequent primary studies. Settled migrants were taken to define movers who have a lengthy stay (5 years) and have no limitations to be economically active in the destination countries. Bearing and raising children was taken to represent parenthood activities of caring for their children which prioritise their well-being, knowledge about their needs, how to accommodate them and creating an environment that promotes children’s development and happiness from birth or before until adulthood (Ainsworth, 1969; Helseth & Ulfsæt, 2005).

Methods

The study used a qualitative synthesis approach which Grant & Booth (2009) defined as ‘a method of integrating or comparing the findings from qualitative studies’. This was deemed appropriate because it generates knowledge which leads to an interpretive translation. It generates constructs and themes across individual qualitative studies focusing on parenting experiences.

Search Strategy

The electronic search journey began in MEDLINE where the search strategy was piloted and then proceeded to other databases; CINAHL, Scopus, Sociological Abstracts, ASSIA and ProQuest Dissertations. These databases were selected because they contain relevant journals in the field and Scopus for its multidisciplinary research base. Reference lists were also scanned to identify any potentially eligible studies not identified in the initial search. Grey literature was sought from the Migration Observatory website, experts, generic web searches through google scholar and review of book chapters. However, no new articles were identified. We derived search terms from concepts of migration, parenting and source country. An illustration of the exhaustive list of search terms as used in MEDLINE are in Table 1 below. The first author conducted all searches allowing for any adjustments to be made.

Search Terms

Article selection

The first author screened research title and abstracts which focused on Settled Southern African migrants experiences by hand. The next stage of full-text review was undertaken by the first author; a second reviewer (co-author) double screened 10% of selected studies and there was no disagreement between reviewers. Studies were included if they met the inclusion criteria. Studies were limited to those published in English, peer-reviewed journals from January 2000 to December 2019. This period was selected as the peak time of qualitative studies on migration from Southern Africa. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised in Table 2 below.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

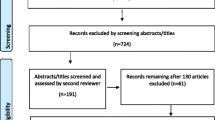

The search journey is documented in a PRISMA diagram below (Fig. 1). The primary studies were conducted in 6 Global North countries in the 14 studies included. Some authors were contacted at this stage to clarify the population of interest as some generalised ‘African’ in their studies. Authors for four papers were contacted and three of them responded.

The PRISMA Flow Diagram

Data charting and critical appraisal of studies

Some aspects (purpose, theoretical framework, methodology, sample, home country, destination country and main results) were extracted from the included studies and tabulated for each of the studies included in this review (see Table A1—Supplementary material). The quality of the studies was assessed using the NICE quality appraisal checklist—qualitative studies. The first author was involved in appraisal and 10% was cross-checked by a co-author. No paper was excluded based on the quality appraisal as none of the studies proved to be too weak in terms of methodological rigour.

Data Analysis

We adopted an approach to thematic synthesis by Thomas & Harden (2008). The first author independently conducted the initial analysis. The 14 included studies were added to analysis software, NVIVO, where their study findings sections were coded verbatim line by line as the first step; and descriptive themes were developed. The codes were created inductively as meaning-making progressed with line by line reading of each primary study. Each study was read repeatedly to ensure that all aspects of the parenting experiences were captured and to familiarise with the data. Free codes were developed at this stage, without any hierarchical structure. As coding for each new study progressed, codes were added to the existing bank of codes and new ones developed as appropriate. All the text which had been assigned codes was examined to see the consistency of interpretation across the synthesis and to see if codes had to be rearranged or added.

This process created a total of 158 codes. We further scrutinised the initial codes and condensed them by grouping them to new codes which captured meanings of the initial codes. This process led to the all co-authors coming to agreement on 12 descriptive themes. We further scrutinised the descriptive themes to finally generate analytical themes which capture experiences and conceptualisation of health and well-being from the parent’s views. This clear focus was necessary as the synthesis is based on literature from individual studies that represented a varied array of study aims. The analytical themes generated new interpretive constructs and explanations; necessary changes were made to ensure all new themes were sufficiently abstract to describe all the initial descriptive themes. We frequently and critically discussed the data analysis process at the different stages of the analysis. This ensured the appropriateness of the analysis process and confirmed that the results were derived from the data. We decided that eight analytical themes addressed directly the concerns of our review and these were categorised under three areas of interest. Figure 1A (supplementary material) outlines the development of themes.

Study Characteristics

The 14 qualitative studies included in this review were carried out in 6 Global North destination countries; Australia (n = 2), Canada (n = 1), New Zealand (n = 1), United States of America (n = 4), United Kingdom (n = 6). These were published between the years 2008 and 2018. Migrant parents’ home countries included Zimbabwe (n = 12), Zambia (n = 3) and South Africa (n = 1); these were within a pool of other countries which did not represent the inclusion criteria (Southern African) in the primary studies. Most of the studies included in this review were qualitative with exception of one (Cook & Waite, 2016) which utilised a mixed method. Six of the studies used exclusively individual interviews for data collection; two studies exclusively used focus group discussion; one study exclusively used group interviews; while the rest used a combination of methods. Two of the studies used photo elicitation techniques alongside individual interviews; one had focus groups and individual interviews; one study included participant observation, in-depth interviews, review of documents (school administered surveys, standardized test scores, school newsletters); the mixed methods study utilised standardized questionnaires and semi-structured individual interviews. Three of the studies did not specify which parent (either mother or father) participated (Dryden-Peterson, 2018; Stuart et al., 2010; McGregor, 2008). Only mothers participated in five of the studies (Agbemenu et al., 2018a, b; Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; Dune & Mapedzahama, 2017; Nyemba & Chitiyo 2018) and exclusively fathers participated in two of the studies (Williams et al., 2012, 2013). Of the remaining four studies both parents were represented; equally across 2 studies (Makoni, 2013; Mupandawana & Cross, 2016) and the other two had majority mothers (n = 56) compared to 36 fathers. Two of the studies also included children (Cook & Waite, 2016; Stuart et al., 2010); and one included resident teachers, school administrators and community leaders (Dryden-Peterson, 2018).

Results

The findings were categorised under three areas of interest; ‘parenting experiences’, ‘sustaining children’s health and well-being’ as well as their intersection ‘parenting experiences and sustaining children’s health and well-being’. Each of the areas of interest will be discussed in turn.

Parenting Experiences

Parenting in the destination countries has proved to be a highly demanding role where settled parents have to operate within new cultural norms and they have a strong desire to protect their children within their parenting practices. Two analytic themes were developed: a balance of many responsibilities and protecting children from the Western world.

A balance of many responsibilities (n = 7)

Most parents from seven papers characterised their parenting experience as involving the burden to tackle many responsibilities (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; Dryden-Peterson, 2018; McGregor, 2008; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018; Stewart et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2013). They feel pressure to balance children’s needs at home and school which are reported to demand a lot of their involvement (Dryden-Peterson, 2018; McGregor, 2008; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018; Stewart et al., 2015). Some referred to the parenting role as being always under time pressure as they balance paid work and raising children; such that they compensate children with technological gadgets (Stewart et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2013). However, some parents made all possible effort to tackle all the associated roles and responsibilities (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; McGregor, 2008; Williams et al., 2012). Several parents reported that they would be less overwhelmed with their parenting responsibility in their home countries where raising children is a shared responsibility in their extended families and the school cultures do not demand a lot of their involvement (Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018; Stewart et al., 2015).

Protecting children from the ‘Western world’ (n = 9)

We identified nine studies in which parents framed their experiences on how they emphasise on protecting their children from any factors that can affect their health, integration in society, education outcomes and cultural values (Agbemenu et al., 2018b; Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; Dune & Mapedzahama, 2017; McGregor, 2008; Mupandawana & Cross, 2016; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018; Stewart et al., 2015; Stuart et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2012). In 9 studies across the UK, Australia and USA some mothers and fathers talked about ensuring their children are well socialised and succeed by offering moral and educational guidance to them as a way to protect them now and their future (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018; Williams et al., 2012).

There were some concerns about racial abuse that children faced in the destination countries and parents revealed how they established open communication with their children to ensure that they are sheltered from racial abuse (Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018; Stewart et al., 2015). This was in reference to their perceptions of their environment being characterised with racial tensions and how minoritised populations were discriminated based on their race. A few articles revealed that parents’ concerns in protecting their children were gendered; where they protect girls from sex which they cited was common in the youth culture in their destination country; and boys from macho and anti-work cultures (Agbemenu et al., 2018b; McGregor, 2008). Some parents in studies on sexual health education reflected that their experiences were more protective in guarding against health interventions offered such as the cervical cancer vaccine because of mistrust of the system (Dune & Mapedzahama, 2017; Mupandawana & Cross, 2016).

However, most parents showed awareness and concern for children’s health and well-being in their practices; this was perceived to be society’s measure of how good they were in protecting their child (Agbemenu et al., 2018b; Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; Dune & Mapedzahama, 2017; Mupandawana & Cross, 2016; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018; Stuart et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2012). Some parents said their traditional cultural values and practices protected their children against risky behaviour; thus, they ought to retain their culture (Mupandawana & Cross, 2016; Stuart et al., 2010).

Sustaining Children’s Health and Well-being

Settled parents have a lot of ideas and ways of thinking about sustaining their children’s health and well-being within their new home. The parents thought of themselves as role models and believed the systems in their destination countries monitored them; as represented in the themes ‘Parents as role models’ and ‘they are keeping an eye on us’.

Parents as role models (n = 7)

Seven papers (50%) described how parents are positioned to influence their children while raising them (Agbemenu et al., 2018a; Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; Cook & Waite, 2016; McGregor, 2008; Stuart et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2013). Some parents revealed that they try and model good practices when thinking about sustaining their children’s health and well-being (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; Stuart et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2012). As such, they avoid displaying unhealthy behaviours such as smoking and drinking (Stuart et al., 2010). However, it proved difficult for some parents as they engaged in those unhealthy or unsocial activities (Williams et al., 2012). Role modelling discussion was linked to respect of religion and culture that was engrained in them from their home countries (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; Stuart et al., 2010). Several parents transfer what they were taught in their home countries out of emulation of how their parents raised them within their cultural context (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; McGregor, 2008; Williams et al., 2013).

In doing so, some parents believed teaching their children their home language would facilitate their identification with their parents’ ethnic culture (Stuart et al., 2010). With the existing destination country culture, they would be developing integrated identities. However, some mothers point out the dangers of what they were not taught by their mothers regarding reproductive health (Agbemenu et al., 2018a), and bringing up girls and boys the same (Cook & Waite, 2016); hence they actively chose to do things differently from their own parents in sustaining their children’s health and well-being.

‘There are keeping an eye on us’ (n = 4)

Issues related to fear that there was a lot of surveillance of some sort were not particularly prominent in most of the included studies. However, in four of the reviewed papers some parents revealed that they felt the strict social services in their destination countries restricted them from having some control over their children (Cook & Waite, 2016; McGregor, 2008; Stewart et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2012). The unacceptability of physical punishment in the destination countries threatened their cultural beliefs and control of their children’s behaviour (Cook & Waite, 2016; McGregor, 2008). In a study on Zimbabwean professionals re-examining their life in the UK, although some parents held on to disciplining practices such as smacking their children, they were more aware of drawing distinctions between abuse and discipline within the acceptable boundaries (McGregor, 2008). In another study on beliefs about fatherhood, health and preventive primary care services; fathers were concerned about the strictness of the safeguarding children function of the primary care services; which meant they had to be aware of and attend to all their children’s vaccinations and health checks (Williams et al., 2012).

Parenting Experiences and Sustaining Children’s Health and Well-being

Some concepts relating to parenting experiences intersected with those on sustaining children’s health and well-being. These contributed to the understanding of parents’ experiences and how they conceptualise children’s health and well-being. The identified themes are: gender role conflicts in parenting, support as being central to the parenting role, compromises and sacrifices for a brighter future for children, home countries influence in parenting practices and place of religion in raising children.

Gender role conflicts in parenting (n = 5)

We identified five studies which expressed a view amongst interviewees that parenting duties and their position in maintaining their children’s health and well-being were met with gender role conflicts (Cook & Waite, 2016; Makoni, 2013; McGregor, 2008; Mupandawana & Cross, 2016; Williams et al., 2013). Particularly with the general belief that women have to be subordinate to men and they are naturally nurturers. Both men and women in a study on gendered identities by dual-career Zimbabwean migrants identified gender differentiation in roles as part of Blackness and most were not willing to adjust to changing times (Makoni, 2013). However, some fathers who were willing to take on some physical parenting roles talked about how women were not confident of their capability (Makoni, 2013; Williams et al., 2013); some women simply did not feel comfortable of role reversal as it seems taboo from their home country (Makoni, 2013). Fathers felt being involved in child-raising responsibilities emasculates them and they were concerned about how their Southern African society would view them (Makoni, 2013). Some women strongly believed raising a baby is their birth-right and had no expectations from their husbands (Makoni, 2013). Renegotiating of roles was a likely cause of most tensions in Southern African migrant’s homes (McGregor, 2008; Mupandawana & Cross, 2016; Williams et al., 2013).

Parents expressed how decision making when it comes to consenting to vaccinate young girls against cervical cancer was mostly discussed by both parents but the final decision for uptake was left to the father (Mupandawana & Cross, 2016). Reinforcing the view that men are superior to women. One study investigating settlement and intergenerational relations in the UK revealed that, although they are gender role conflicts among parents’ generation, parents are more aware of the importance of raising girls and boys with the belief that they can have the same roles in the family and community (Cook & Waite, 2016).

Support as being central to the parenting role (n = 11)

A recurrent theme in 11 papers was a sense amongst parents that support was central to their parenting role (Agbemenu et al., 2018a; Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; Cook & Waite, 2016; Dryden-Peterson, 2018; Dune & Mapedzahama, 2017; McGregor, 2008; Mupandawana & Cross, 2016; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018; Stewart et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2012, 2013). Support from husbands to reflect the gender role dynamics in childcare within their destination countries was discussed (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; McGregor, 2008; Williams et al., 2013). While some mothers reported that fathers did not make role adjustments to support their wives in raising their children (Stewart et al., 2015), other fathers valued partnership in child-rearing and they evolved from the assigned gender roles they were raised into (Stewart et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2013). Some men discussed how child health services in the UK were mainly available for women and not designed for men, which limited their support in maintaining children’s health in early childhood (Williams et al., 2012).

Parents struggled with childcare even when both parents were working; this was extreme for single-parent households who faced worse financial struggles that strained child-care arrangements especially when they did not have close relatives for support (McGregor, 2008; Stewart et al., 2015). Social isolation was reported by some mothers who raised their children without the support of friends and family like they had in their home countries which would have eased their parenting (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; McGregor, 2008). Fathers also agreed that their home country offered opportunities for extended family to support in child-rearing (Stewart et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2013).

Parents also indicated the need for family support in assuming the role of sexual health teachers since their traditional culture makes it an uncomfortable topic to be discussed between parents and children (Agbemenu et al., 2018a; Dune & Mapedzahama, 2017; Mupandawana & Cross, 2016). However, some parents leaned on the church community for support or just stepped in themselves despite the uncomfortableness (Dune & Mapedzahama, 2017).

Lack of community support in their localities was highlighted as it limits their access to information about the services available to them (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018). Support from children’s schools was reflected in levels of communication (Dryden-Peterson, 2018; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018). However, one study reported that the schools did not offer extra support for the immigrant parents to understand resources available to them within the school and externally (Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018).

Compromises and sacrifices for a brighter future for children (n = 8)

Eight papers described a sense of compromises and sacrifices amongst parents in their parenting journey (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; Cook & Waite, 2016; Dryden-Peterson, 2018; McGregor, 2008; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018; Stuart et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2012, 2013). Being a parent was seen as a loss of self and adoption of ‘parent’ as the only or significant identity by many parents (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018; Williams et al., 2012). Other parents were not satisfied with the sacrifices they made (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; Williams et al., 2012). For instance, some fathers neglected their health to focus on the children’s well-being (Williams et al., 2012); while some women neglected interests and compromised their time to focus on the children’s well-being (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017). They were also focused on creating a successful future by providing the best educational opportunities for their children which they may not have had; hence, moving to the Global North was deemed a sacrifice to provide such (Dryden-Peterson, 2018; McGregor, 2008; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018; Stuart et al., 2010). Thus, when thinking about the choice of schools and their level of involvement; parents had a lot of considerations to put their children in an environment that values their future success path and in which they would get support to succeed (McGregor, 2008; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018; Stuart et al., 2010).

As mentioned earlier, there is a level of perceived limitation on the disciplinary practices that parents can exercise, with some widely experiencing a sort of independence by children in the destination countries (Cook & Waite, 2016; McGregor, 2008; Stuart et al., 2010). Parents compromised by adopting their destination countries approach to instilling discipline in their children, by mostly using communication as a tool instead of physical punishment (Stuart et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2013). Cultural disparities related to discipline raised concerns about whether to send children to be raised by extended family in their home countries so they can embrace their traditional culture (McGregor, 2008). However, Cook & Waite (2016) revealed that some parents were embracing new parenting approaches in the destination country to enable them to live transnationally across two cultures. The arising conflict between parents and children fuelled positive outcomes by improving communication (Stuart et al., 2010).

Place of religion in raising children (n = 4)

We identified four papers reporting a variety of perspectives about the place of religion in raising children. Parenting role was partly defined by being able to provide religious protection and applying its guiding principles in raising children (Dune & Mapedzahama, 2017; Mupandawana & Cross, 2016; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018; Williams et al., 2012). In one study, some parents revealed their choice of sending their children to Catholic schools which they believed nurtured good behaviour (Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018). In this light, some parents believe religious children will not be at risk of sexual diseases (Dune & Mapedzahama, 2017; Mupandawana & Cross, 2016). Some parents believed that the best source of information relating to sexual health was the church which considers their home country identity; and the combination of faith, education and priorities would reduce their children’s risk (Dune & Mapedzahama, 2017; Mupandawana & Cross, 2016).

Discussion

This qualitative synthesis identified eight analytic themes describing the experiences of migrant parents in their destination countries. These themes were drawn from the perspectives of the parents who shared their lived experience of parenting across 14 primary studies. An extensive amount of qualitative research exists on migrants’ parenting experiences; this is however, the first qualitative synthesis to gather contemporary qualitative evidence on settled Southern African migrants’ experiences of bearing and raising children in Global North destination countries; and to collate qualitative evidence on how they conceptualise sustaining children’s health and well-being in these destination countries. Our themes illuminate the nature of Southern African families and how their values shape their experiences.

This study used a systematic search process, followed a transparent planning and reporting guideline (ENTREQ statement), and documented the analysis process using Thomas & Harden’s (2008) thematic synthesis procedure. Another strength of the study is the approach to the review which allowed a broad range of parenting experiences to be captured from diverse populations living in a few high-income Global North destination countries. The analysis integrated all these aspects and some studies had methodological strongpoints because of use of visual methods to elicit responses and support parents to give voice to their responses (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017; Makoni, 2013). Although several efforts were put to enhance the rigour of the study, the results of this synthesis should be interpreted with consideration of several limitations. Firstly, although a specific broad migrant group (Southern Africa) was studied, the authors synthesised primary studies where source countries of participants included in the primary studies were diverse including other migrant groups from other African Countries. Critics have also argued that most studies suffer from viewing Black families as a homogenous entity instead of explaining differences in experiences according to ethnicities (Ochieng & Hylton, 2010). Experiences are shaped by multiple factors; hence future research should study migrants as distinct groups to better apply a transnational lens to further understand these experiences in their home countries. Approaching this synthesis, we expected to gather a diverse data set comprising of different Southern African Countries. However, the systematic search strategy and objective selection led to the inclusion of dominantly Zimbabwean migrant groups (twelve studies) and Zambian migrants (three studies). Therefore, interpretation of this synthesis might be most relevant to these Southern African groups. In line with the nature of qualitative research, the primary studies included small samples that at times have unique characteristics which limit the confidence with which generalisations can be made from the themes identified. However, these findings may help us to understand the nature of the literature on migrant parents’ experience. From the demographics represented, most of the participants represented in the included studies are mothers. These results should be interpreted with caution; future research should engage experiences of both parent figures and also extended family. Lastly, although we have documented the analysis process, it is possible that other researchers may interpret the data differently as our interpretation was influenced by our backgrounds and identities. One author self-identified as Black African, another Black Caribbean and the rest identified as White British. One of the authors was raised in a migrant family, another migrated as an adult after being raised in a Southern African family, whilst the rest were born and raised in the UK. Four of the authors were also mothers at the time of drafting this manuscript. These findings should be considered in the context of their strengths and limitations.

This synthesis shows that migrant parents’ loss of support from extended family after migration makes parenting an isolating experience. This is echoed by another qualitative synthesis focusing on African parents’ practices, which revealed that kinship is lost post-migration (Salami et al., 2017). Within their diversity, most African families come from an extended family which constitutes biological relations, non-biological relations and extended cousins who function in a collective culture where supporting each other in raising children is central (Mugadza et al., 2019). The findings of our study show how parenting in destination countries has changed to become a matter only for both parents. International migration has broken social bonds of amity that African families thrive on.

We highlighted that power distribution when it comes to vaccination decision was more skewed towards the father as the key decision-maker. In most African societies the gender system fosters power imbalances that support men as the key decision makers. These studies have also highlighted that gender roles changed post-migration; challenging the traditionally assigned roles when raising children in their home countries. There is no single model of gender roles in Southern Africa, however, in the African culture and traditional life there is a general understanding that men assume dominant roles of being the breadwinners and key decision makers while women are expected to be subordinate homemakers dealing with childrearing and household upkeep (Ngubane, 2010). The notion that men are losing their power in their families through their involvement in child-rearing due to migration is apparent in this synthesis. Although there are several parallels between the findings, a large number indicated they were comfortable with renegotiating roles within their households, especially given the involvement of women in the workforce. The social constructionist theory helps us to understand this renegotiation as it recognises that role allocation varies widely based on norms for masculinity and femininity that are subscribed to (Benza & Liamputtong, 2017). Gender roles are often mutually agreed upon; hence both parents go through the process of changing their attitudes towards gender roles in raising the children in a new environment.

We found that parents incorporate religion into most aspects of their parenting including school choices, teachings on acceptable behaviour, source of protection, and consequently sustaining one’s health and well-being. These results are in agreement with those obtained by Munroe et al. (2016) on African immigrant mothers with an autistic child/ren in the UK who place religion as central to all activities. Furthermore, religion is also a protective feature in many Global North families’ accounts of challenges in raising their children (Marshall & Long, 2010). This study confirms that parents’ religiosity can influence what behaviours and beliefs are modelled for children (Petro et al., 2018). It is noteworthy that other factors such as culture, parenting styles and faith community structures affect how religion is incorporated in raising children.

Engagement and investment in their children’s education and future success was viewed as priority, especially as it was a factor which motivated their decisions to settle in the destination countries. Involvement in children’s education was portrayed as an important part of parenting practices. However, other parents identified pressures which limit their engagement. These results seem to be consistent with other research which found that migrant parents are less involved in their children’s education (Bergset, 2017; Free et al., 2014; Hamilton, 2013). This has an impact on the establishment of meaningful links with schools. Other studies found that institutional barriers and stereotypical assumptions are some of the factors inhibiting the establishment of meaningful connections and consequently impact on children’s life chances (Bubikova-Moan, 2017; Hamilton, 2013). Therefore it is crucial for institutions to understand migrant families within the context of the layers of influence that shape them and not perpetuate deficit views.

In this study, parents were found to be highly conscious of their actions because of the safeguarding measures placed on children concerning discipline and vaccinations. This also accords with earlier findings, which showed that children are informed by the schools and government agencies of their rights and freedoms which was deemed interference by Somali parents (Degni et al., 2006). In contrast, Ochieng & Hylton (2010) noted a rise in children from Black families in the social care system. A recent review by Mugadza et al. (2019) based on Australian studies also noted a rise in notifications to child protection services regarding suspected abuse and neglect by families from migrant backgrounds. This might indicate how the families are disempowered in navigating the socio-political environment. For most immigrants from African countries, government involvement in family life is foreign to them and the significance of corporal punishment is shared by many disciplinary actors. Their view of the government involvement is largely suspicious (Rasmussen et al. 2012). It is also possible that foreign-born parents make a lot of assumptions about how the system facilitates the integration of children into the destination society based of misconceptions about the system (Degni et al., 2006; Ochieng & Hylton, 2010). Understanding their perceptions on public authority is important to determine their willingness to engage with public institutions which are critical in maintaining a healthy family life.

This synthesis demonstrates that communication has been adopted as a tool to strengthen parent–child relationships and to better understand children’s needs. The results seem to be consistent with other research which found that parents from collective cultures now living in individualistic cultures which are dominant in the Global North move towards allowing their children to have the autonomy, individual responsibility and establish firm individual boundaries (Renzaho et al., 2017). This study supports evidence from previous observations of a hierarchy system that operates in most African families which only gives voice to the parents (Bukuluki, 2013). This means parents move from the authoritarian parent style they were raised on to a more power balanced style where communication is open; this likely raises difficulties in negotiating cultures (Andre et al., 2017; Degni et al., 2006; Londhe, 2014).

Considerations for sending children to home countries to reinforce their ethnic identity were represented in one of the studies as shown in the theme ‘Compromises and sacrifices for a brighter future for children’. This was intended to also bridge the struggles they have in balancing between the home culture and destination country norms in maintaining their children’s health and well-being. ‘Culture is to society what memory is to individuals’ (Diener & Suh, 2000, p.13). Therefore, it is possible that in their effort to build their children’s identities, immigrant parents send their children to their home countries to uphold practices and values they were raised in (Londhe, 2014). This combination of findings provides some insight into the significant role played by culture in shaping experiences of parenting and influencing parenting practices.

Conclusion

The added value of this qualitative synthesis is that all in-cooperated studies collectively cover diverse disciplinary angles, topics, and target groups in relation to the study focus. Migrants bring with them diverse knowledge and cultural practices relating to health. It is crucial to understand how they conceptualise health, in order to give their children a good start in life. The results of this review indicate the migrant parents’ experiences are largely rooted in the way they were raised in their home countries. Although the articles had heterogeneous populations, the experiences were common across groups such as loss of support, religion’s influence in parenting and gender role conflicts. The different Global North destination countries can influence the common themes because they share some common values, systems and social policies which influence family life. Nevertheless, these commonalities should not mask the need to understand experiences of specific groups in terms of country of origin, destination country, belief systems and cultural references. We have sacrificed depth for scope, and recognise the need to expand work in extensively investigating these groups separately as well as understand the nuances between them. These findings can be also used to support the voice of settled migrants in the evidence base that can be used to facilitate their integration in the Global North destination countries. It is important to understand their experiences in providing appropriate services and support. This study represents an opportunity to ‘give voice’ to these under-represented and under-researched migrant parents’ experiences. Future research should extend beyond the broad geographical focus.

References

Adserà, A., & Tienda, M. (2012). Comparative perspectives on international migration and child well-being. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 643(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716212445742

Agbemenu, K., Devido, J., Terry, M. A., Hannan, M., Kitutu, J., & Doswell, W. (2018a). Exploring the experience of African immigrant mothers providing reproductive health education to their daughters aged 10 to 14 years. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 29(2), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659616681848

Agbemenu, K., Hannan, M., Kitutu, J., Terry, M., & Doswell, W. (2018b). “Sex will make your fingers grow thin and then you die”: The interplay of culture, myths, and taboos on African immigrant mothers’ perceptions of reproductive health education with their daughters aged 10–14 years. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20(3), 697–704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0675-4

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1969). Object relations, dependency, and attachment: a theoretical review of the infant–mother relationship. Child Development, 969–1025. https://doi.org/10.2307/1127008

Alemi, Q., & Stempel, C. (2018). Discrimination and distress among Afghan refugees in Northern California: the moderating role of pre- and post-migration factors. PloS ONE, 13(5), e0196822. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196822

Altschuler, J. (2013). Migration, illness and health care. Contemporary Family Therapy; An International Journal, 35(3), 546–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-013-9234-x

Andre, M. N. R., Dhingra, N., & Georgeou, N. (2017). Youth as contested sites of culture: the intergenerational acculturation gap amongst new migrant communities-parental and young adult perspectives. PLoS ONE, 12, e0170700. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170700

Benza, S., & Liamputtong, P. (2017). Becoming an ‘Amai’: meanings and experiences of motherhood amongst Zimbabwean women living in Melbourne, Australia. Midwifery, 45, 72–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.12.011

Bergset, K. (2017). School involvement: refugee parents’ narrated contribution to their children’s education while resettled in Norway. Outlines: Critical Practice Studies, 18(1), 61–80

Bubikova-Moan, J. (2017). Negotiating learning in early childhood: narratives from migrant homes. Linguistics and Education, 39, 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2017.04.003

Bukuluki, P. (2013). “When I steal, it is for the benefit of me and you”: Is collectivism engendering corruption in Uganda? International Letters of Social and Humanistic. Sciences, 5, 27–44

Condon, L. J., & McClean, S. (2017). Maintaining pre-school children’s health and well-being in the UK: a qualitative study of the views of migrant parents. Journal of Public Health, 39(3), 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdw083

Confraria, H., Godinho, M. M., & Wang, L. (2017). Determinants of citation impact: a comparative analysis of the Global South versus the Global North. Research Policy, 46(1), 265–279

Cook, J., & Waite, L. (2016). ‘I think I’m more free with them’—conflict, negotiation and change in intergenerational relations in African families living in Britain. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(8), 1388–1402. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1073578

Degni, F., Seppo, P., & Mulki, M. (2006). Somali parents’ experiences of bringing up children in Finland: exploring social-cultural change within migrant households. Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-7.3.139

Diener, E., & Suh, E. M. (2000). Culture and subjective well-being (well-being and quality of life). The MIT Press

Dryden-Peterson, S. (2018). Family–school relationships in immigrant children’s well-being: the intersection of demographics and school culture in the experiences of Black African immigrants in the United States. Race Ethnicity and Education, 21(4), 486–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2017.1294562

Dune, T., & Mapedzahama, V. (2017). Culture clash: Shona (Zimbabwean) migrant women’s experiences with communicating about sexual health and well-being across cultures and generations. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 21(1), 18–29

Eten, S. (2017). The role of development education in highlighting the realities and challenging the myths of migration from the global south to the global north. Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, 24, 47–69

Fernández-Reino, M. (2020). The health of migrants in the UK. The Migration Observatory. https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/the-health-of-migrants-in-the-uk/

Free, J. L., Križ, K., & Konecnik, J. (2014). Harvesting hardships: educators’ views on the challenges of migrant students and their consequences on education. Children and Youth Services Review, 47, 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.08.013

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Hamilton, P. (2013). Fostering effective and sustainable home-school relations with migrant worker parents: a new story to tell? International Studies in Sociology of Education, 23(4), 298–317. 10.1080/09620214.2013.815439

Helseth, S., & Ulfsæt, N. (2005). Parenting experiences during cancer. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03562.x

Londhe, R. (2014). Acculturation of Asian Indian parents: relationship with parent and child characteristics. Early Child Development and Care, 185(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2014.939650

Makoni, B. (2013). ‘Women of the diaspora’: a feminist critical discourse analysis of migration narratives of dual career Zimbabwean migrants. Gender and Language, 7(2), 201–229. https://doi.org/10.1558/genl.v7i2.203

Marshall, V., & Long, B. C. (2010). Coping processes as revealed in the stories of mothers of children with autism. Qualitative Health Research, 20(1), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309348367

McGregor, J. (2008). Children and ‘African values’: Zimbabwean professionals in Britain reconfiguring family life. Environment and Planning A, 40(3), 596–614. 10.1068/a38334

Mugadza, H., Mujeyi, B., Stout, B., Wali, N., & Renzaho, A. (2019). Childrearing practices among Sub-Saharan African migrants in Australia: a systematic review. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2927–2941. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01463-z

Munroe, K., Hammond, L., & Cole, S. (2016). The experiences of African immigrant mothers living in the United Kingdom with a child diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder: an interpretive phenomenological analysis. Disability & Society, 31(6), 798–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2016.1200015

Mupandawana, E. T., & Cross, R. (2016). Attitudes towards human papillomavirus vaccination among African parents in a city in the North of England: a qualitative study. Reproductive Health, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-016-0209-x

Nannestad, P., Svendsen, G. T., Dinesen, P. T., & Sønderskov, K. M. (2013). Do institutions or culture determine the level of social trust? The natural experiment of migration from non-western to western countries. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(4), 545–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.830499

Nesteruk, O., & Marks, L. D. (2011). Parenting in immigration: experiences of mothers and fathers from Eastern Europe raising children in the United States. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 42(6), 809–825

Ngubane, S. J. (2010). Gender roles in the African culture: implications for the spread of HIV/AIDS. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Stellenbosch. http://hdl.handle.net/10019.1/4195

Nyemba, F., & Chitiyo, R. A. (2018). An examination of parental involvement practices in their children’s schooling by Zimbabwean immigrant mothers in Cincinnati, Ohio. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 12(3), 124–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595692.2017.1408585

Ochieng, B. M. N., & Hylton, C. (2010). Black families in Britain as the site of struggle (1st ed.). Manchester University Press

Petro, M. R., Rich, E. G., Erasmus, C., & Roman, N. V. (2018). The effect of religion on parenting in order to guide parents in the way they parent: a systematic review. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 20(2), 114–139

Rasmussen, A., Akinsulure-Smith, A., Chu, T., & Keatley, E. (2012). “911” among West African immigrants in New York City: a qualitative study of parents’ disciplinary practices and their perceptions of child welfare authorities. Social Science & Medicine, 75(3), 516–525

Renzaho, A. M. N., Dhingra, N., & Georgeou, N. (2017). Youth as contested sites of culture: the intergenerational acculturation gap amongst new migrant communities-parental and young adult perspectives. Plos ONE, 12(2), e0170700. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170700

Renzaho, A. M. N., Green, J., Mellor, D., & Swinburn, B. (2011). Parenting, family functioning and lifestyle in a new culture: the case of African migrants in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Child & Family Social Work, 16(2), 228–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2010.00736.x

Salami, B., Hirani, S. A. A., Meherali, S., Amodu, O., & Chambers, T. (2017). Parenting practices of African immigrants in destination countries: a qualitative research synthesis. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 36, 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2017.04.016

Stewart, M., Dennis, C., Kariwo, M., Kushner, K., Letourneau, N., Makumbe, K., Makwarimba, E., & Shizha, E. (2015). Challenges faced by refugee new parents from Africa in Canada. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17(4), 1146–1156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0062-3

Stuart, J., Ward, C., Jose, P. E., & Narayanan, P. (2010). Working with and for communities: a collaborative study of harmony and conflict in well-functioning, acculturating families. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34(2), 114–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.11.004

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(45). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

United Nations. (2019). Refugees and migrants. https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/

United Nations Population Fund. (2019). Migration. http://www.unfpa.org/migration

Vathi, Z. (2015). Migrating and settling in a mobile world: Albanian migrants and their children in Europe. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13024-8

Williams, R., Hewison, A., Stewart, M., Liles, C., & Wildman, S. (2012). ‘We are doing our best’: African and African‐Caribbean fatherhood, health and preventive primary care services, in England. Health & Social Care in the Community, 20(2), 216–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01037.x

Williams, R., Hewison, A., Wildman, S., & Roskell, C. (2013). Changing fatherhood: an exploratory qualitative study with African and African Caribbean men in England. Children & Society, 27(2), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2011.00392.x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Machaka, R., Barley, R., Serrant, L. et al. Parenting among Settled Migrants from Southern Africa: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. J Child Fam Stud 30, 2264–2275 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02013-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02013-2