Abstract

Steroid hormones play important roles in brain development and function. The signaling of steroid hormones depends on the interaction between steroid receptors and their coactivators. Although the function of steroid receptor coactivators has been extensively studied in other tissues, their functions in the central nervous system are less well investigated. In this study, we addressed the function of steroid receptor coactivator 3 (SRC3) – a member of the p160 SRC protein family that is expressed predominantly in the hippocampus. While hippocampal development was not altered in Src3+/− mice, hippocampus-dependent functions such as short-term memory and spatial memory were impaired. We further demonstrated that the deficient learning and memory in Src3+/− mice was strongly associated with the impairment of long-term potentiation (LTP) at Schaffer Collateral-CA1 synapses. Mechanistic studies indicated that Src3+/− mutation altered the composition of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits in the postsynaptic densities of hippocampal neurons. Finally, we showed that SRC3 regulated synaptic plasticity and learning mainly dependent on its lysine acetyltransferase activity. Taken together, these results reveal previously unknown functions of SRC3 in the hippocampus and thus may provide insight into how steroid hormones regulate brain function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Steroid hormones and their receptors play important roles in brain development and function [1], and steroid receptors act in a classic genomic signaling pathway to bind with target DNA and alter gene transcription [2]. In addition, these receptors can act in a rapid, non-genomic manner to activate intracellular signaling pathways [3]. The relative abundance and interactions between steroid receptors and their co-activators determine the cellular responses to steroid hormones [4, 5]. Steroid receptor co-activators (SRCs) have been extensively studied in the fields of cancer, metabolism, endocrinology, and development [6,7,8,9,10], but the functions of SRCs in the adult brain are relatively less well studied [11].

The SRC family of p160 proteins consists of SRC1, SRC2, and SRC3. These coactivators physically interact with steroid receptors, including androgen, progesterone, and estrogen receptors as well as receptors for glucocorticoids, in a ligand-dependent manner [12,13,14]. SRC1 and SRC2 are widely expressed in several brain regions such as the cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, cerebellum, and hypothalamus [15, 16]; they have been shown to regulate a variety of brain functions such as sexual behaviors [17, 18], energy homeostasis [19, 20], learning and memory [21, 22], and the motor function of the cerebellum [15]. Compared to SRC-1 and SRC-2 whose functions in the brain have been studied [23], the functions of SRC3 in the brain remains largely unknown.

SRC3 (also known as p/CIP, RAC3, AIB1, ACTR, TRAM1, and NCOA3) has been implicated in regulating steroid hormone signaling [24]. Its N-terminus contains a basic helix-loop-helix domain that is required for interaction with transcription factors. The central region of SRC3 contains a nuclear receptor interaction domain (RID) that is responsible for the interaction with nuclear receptors. The C-terminus of SRC3 contains the acetyltransferase (KAT) domain. Unlike SRC1 and SRC2, SRC3 is expressed predominantly in the hippocampus and very sparsely in the hypothalamus [6, 15]. In this study, we addressed the function of SRC3 in synaptic plasticity and hippocampus-dependent memory by virtue of the Src3+/− mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6N male mice 7–8 weeks old were used in experiments unless otherwise described. Animals were housed in rooms at 23 °C and 50% humidity under a 12 h light/dark cycle and with food and water available ad libitum. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of East China Normal University. Src3+/− mutant mice were described in a previous study [6] and were backcrossed with C57BL/6N mice for >10 generations before experiments.

Subcellular Fractions

Subcellular fractions were obtained as described previously [25] with modifications. Mouse brain tissue was homogenized in Buffer A (0.32 mol/L sucrose, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L PMSF, and a protease inhibitor cocktail). Homogenates were passed through a filter to remove cell debris and centrifuged at 500×g for 5 min in a fixed angle rotor to yield the P1 (nuclear) and S1 (cytosolic) fractions. The P1 fraction was washed in Buffer B containing 10 mmol/L KCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 500×g for 5 min. The pellets were dissolved in Buffer C containing 20 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.9), 25% glycerol, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1.4 mol/L KCl, 0.2 mmol/L EDTA, 0.2 mmol/L PMSF (phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride), 0.5 mmol/L DTT (1, 4 dithiothreitol) and incubated on a shaker at 4 °C for 30 min. After centrifugation at 12,000×g for 10 min, the supernatant of P1 was collected as nuclear proteins. The S1 fraction was centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min to yield P2 that contained membranes and synaptosomes, and the cytoplasmic S2. To further purify the postsynaptic fractions, synaptosomes in 0.8 mol/L sucrose were mixed with 1/19 volume of Buffer D containing 200 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.0), 20% Triton X-100, and 1.5 mol/L KCl. Samples were centrifuged at 20,800×g for 45 min using a fixed angle rotor. The pellets were re-suspended in Buffer E containing 1% Triton X-100 and 75 mmol/L KCl using a Dounce mini-homogenizer and centrifuged again at 20,800×g for 30 min to yield a final pellet—the PSD (postsynaptic density) fraction, which was washed with 20 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.9) and dissolved in 1 × SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

Western Blot

Western blotting was performed as described in previous studies [25, 26]. Nuclear and S2 solutions were mixed with 6 × SDS-PAGE sample buffer. P2 and PSD fractions were directly dissolved in 1 × SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Respective subcellular fractions were resolved on SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which were incubated in Tris-HCl buffer containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% milk for 1 h at room temperature before incubation with a primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. After washing, the membranes were incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody in the same TBS buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by the ChemiDocTM XRS+ Imaging System (BIO-RAD) using enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce) and analyzed with ImageJ (NIH). The primary antibodies used were as follows: anti-SRC3 (5765, Cell Signaling, Boston, USA); anti-α-tubulin (3873, Cell Signaling); anti-Synapsin1 (2312, Cell Signaling); anti-Histone H3 (9715, Cell Signaling); anti-Calmodulin (05-173, Millipore, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany); anti-CaMKIIα (11945, Cell Signaling); anti-phospho-CaMKIIα (pThr286) (SAB4300228, Sigma, Merck KGaA); anti-NR2A (04-901, Millipore); anti-NR2B (MAB5778, Millipore); anti-GluR1 (ab109450, Abcam, Cambridge, UK); anti-GluR2 (MABN71, Millipore).

Immunofluorescence

Brain slices were fixed in 4% PFA, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton-X 100 and 5% BSA in PBS and incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After washing 3 times with PBS, samples were incubated with Alexa Fluor-594-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500; A-11032, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. The samples were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector) and images were captured using a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope or by Leica stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy. The following primary antibody were used: rabbit anti-NeuN (Abcam, ab177487); rabbit anti-SRC3 (Cell Signaling, 5765); mouse anti-PSD95 (Millipore, MAB1596); Biocytin (Sigma, B4261); and Alexa Fluor-488-conjugated anti-Biocytin (Thermo Fisher, S32354).

β-Gal Detection

Src3+/− mice were killed and perfused with ice-cold saline. Brain slices embedded in 3% agar were cut into 100 μm slices on a Vibratome (VT 1000S, Leica). β-Gal activity was assessed using an in situ β-galactosidase staining kit (Beyotime, RG0039, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The slices were washed, mounted in Permount (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and imaged using a microscope with a high-sensitivity camera and equipped with a Plan-Neofluar 5×/0.30 NA objective lens (Leica DMI3000 B).

Chemical Long-Term Potentiation (LTP)

Chemical LTP stimulation in hippocampal slices was performed as previously described [27]. Briefly, chemical LTP was induced by incubating slices for 15 min in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) lacking MgCl2 and containing 4 mmol/L CaCl2, 100 μmol/L picrotoxin, 50 μmol/L forskolin, and 100 nmol/L rolipram. After stimulation, the slices were homogenized and the total lysates were subjected to Western blotting.

Electrophysiology

Slice Preparation

Male mice (7–8 weeks old) were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium, decapitated, and the brains were quickly removed and chilled in ice-cold aCSF for an additional 1 min. Transverse hippocampus slices (350 μm) were prepared using a Vibroslice (VT 1000S; Leica, Nussloch, Germany) in ice-cold aCSF. The slices were then incubated in regular aCSF containing (in mmol/L): 126 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1.0 MgSO4, 2.0 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 glucose for 30 min at 34 °C for recovery, and then at room temperature (25 ± 1 °C) for an additional 2–8 h. For whole-cell recording, mice were perfused transcardially for 1 min with ice-cold modified solution (in mmol/L): 110 NMDG (N-Methyl-D-glucamine), 2.5 KCl, 10 MgSO4, 0.5 CaCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 25 glucose, to protect neurons and maintain the functional connectivity of brain slices. All solutions were saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2 (vol/vol).

Whole-cell Patch-clamp Recording

CA1 neurons were visualized with infrared optics using an upright microscope equipped with a 40× water-immersion lens (BX51WI; Olympus, Monolith, Japan) and infrared-sensitive CCD camera. The pipettes were filled with the solution (in mmol/L): 105 K-gluconate, 30 KCl, 10 HEPES, 0.3 EGTA, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP, and 10 phosphocreatine sodium (pH 7.3, 280 mOsm). For the spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current (sEPSC) recording, the membrane potential was held at −70 mV under voltage-clamp. The action potential was recorded under current-clamp. Neurons were held at –70 mV, and injected with different currents (duration, 500 ms; increments, ±20 pA from −200 to 580 pA; interval, 10 s). All data were obtained with an EPC10 double patch-clamp amplifier (HEKA Elektronik, Reutlingen, Germany). Data were low-pass filtered at 10 kHz and digitally sampled at 10 kHz with PatchMaster version 2x90.1. Data were analyzed with Neuromatic version 3.0 (http://www.neuromatic.thinkrandom.com, London, England) which runs within Igor pro 6.7.3.2 (WaveMetrics, Poland, USA).

LTP Recording and Quantification

Hippocampal slices from 7–8-week-old male mice were placed in a recording chamber and continuously superfused with pre-warmed (32 ± 1 °C) aCSF at 3 mL/min. Field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSP) were evoked (0.1-ms current pulses at 0.033 Hz) in the CA1 stratum radiatum by stimulating Schaffer collaterals (SCs) with a concentric bipolar stimulating electrode (FHC, Bowdoin, USA) and recorded in current-clamp using an EPC 10 amplifier (HEKA Elektronik) with aCSF-filled glass pipettes (1–5 MΩ). LTP was induced using three trains of theta burst stimulation (10 bursts at 5 Hz, each of 50 pulses at 100 Hz) at inter-train intervals of 30 s [28, 29]. All data were acquired at a 10 kHz sampling rate using Patchmaster version 2x90.1 software (HEKA Elektronik) and filtered off-line at 2 kHz. Analysis was performed with Neuromatic version 3.0 (http://www.neuromatic.thinkrandom.com). Each EPSP trace was normalized to baseline. Two consecutive EPSP traces were averaged to generate a 1-min bin, which generated LTP summary time-course graphs. For LTP of field potentials, the magnitude of LTP was calculated as an average of normalized EPSP amplitudes 50–60 min after TBS.

Stereotaxic Injection of Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV)

To generate AAVs that express the KAT and RID domains of SRC3, we first subcloned the cDNA of the KAT or RID domain from human SRC3 into the pAAV-Syn1 promoter-EGFP-p2A-MCS-3Flag vector before packaging the AAVs. All the AAVs were generated by OBiO Technology Corp., Ltd.

For virus injection, 5-week-old Src3+/− mice were anesthetized with 1% pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg, i.p.) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (RWD Life Science, Shenzhen, China). Viruses were injected bilaterally into the CA1 regions of hippocampus at the coordinates: anteroposterior −2.7 mm, mediolateral ±2.25 mm, dorsoventral −1.625 mm relative to bregma. Each injection used 0.5 µL AAV and took 5 min. After the injection, the glass pipette was left in place for 5 min to facilitate diffusion of the virus. The injection sites were examined at the end of the experiments, and animals with incorrect injection sites were excluded from the data analysis. Three weeks after AAV injection, mice were subjected to experiments. All surgery was conducted using aseptic techniques.

Novel Object Recognition

In the habituation phase, individual adult male mice were placed in a chamber (50 cm × 50 cm × 40 cm) and allowed to freely explore the context for 10 min while being recorded by an overhead camera. In the sampling phase, the animal was placed in the same chamber containing two different objects and allowed to explore them for 5 min. To saturate the odor left by the previous mice and to make the mice more relaxed, we placed standard animal bedding in the chamber. Each mouse was tested 1 h after training. In the testing phase, one of the objects was replaced by a new one, and the time spent exploring each of the two objects was separately recorded using ANY-MAZE software. The discrimination index was calculated using the following formula: (time exploring novel object − time exploring familiar object)/(time exploring novel object + time exploring familiar object).

Morris Water Maze

The Morris water tank consisted of a circular pool (diameter 120 cm, height 50 cm) filled with water maintained at room temperature (25 ± 1 °C) and made opaque with nontoxic white paint. Mice were trained for 5 days with 4 trials per day and 120 s per trial. We used 3 extra-maze visual cues to ensure that visual spatial memory was used by the mouse to find the location of the hidden platform. Twenty-four hours after the last training trial (day 6), the platform was removed and each mouse were given one trial for 60 s of searching (probe test).

Statistics

All data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Comparisons between two groups were made using the two-sided t-test. Comparisons between three or more groups were made using one-way ANOVA analysis followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Data from Sholl analysis, paired-pulse facilitation, I/O curves of action potentials, LTP, locomotion, and the learning curve in Morris water maze were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. Statistically significant difference was indicated as follows: ***P <0.001, **P <0.01, and *P <0.05. The statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism 8.

Results

Subcellular Distribution of SRC3 in Mouse Hippocampus

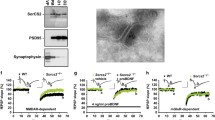

To investigate the subcellular distribution of SRC3, we separated adult mouse hippocampal cells into nuclear (N), cytosolic (S2), and membrane (P2) fractions. The purity of these fractions was confirmed by the enrichment of different markers: histone protein H3 in the N, α-tubulin in the S2, and synapsin 1 in the P2 fractions (Fig. 1A). In addition to the nucleus, SRC3 was also expressed in the cytoplasm and P2 fractions (Fig. 1A). To further study the distribution of SRC3 in the synapse, we purified the synaptosomal presynaptic (Pre) and postsynaptic density (PSD) fractions. The purity of the Pre and PSD fractions was evidenced by the enrichment of synapsin 1 in the Pre, and PSD95 in the PSD (Fig. 1B). We found that SRC3 was expressed in the synaptosomes and was more enriched in the PSD than Pre (Fig. 1B).

Subcellular distribution of SRC3 in adult mouse hippocampus. A Upper panels. expression of SRC3 in the nuclear (N), cytoplasmic (S2) and membrane (P2) fractions. Histone H3, α-tubulin, and synapsin 1 are the protein markers for the N, S2 and P2 fractions. Lower panel, Ponceau staining to show equal protein loading. B Upper panels, expression of SRC3 in synaptosome (Syn), presynaptic (Pre), and postsynaptic (PSD) fractions. Synapsin 1 and PSD95 are the protein markers for Pre and PSD fractions. Lower panel, Ponceau staining to show equal protein loading. C Confocal microscopic, immunofluorescence images of SRC3 in the mouse CA1 hippocampal region (scale bar, 50 µm). D Upper panel, STED microscopic immunofluorescence image of SRC3 and PSD95 in the mouse CA1 hippocampal region (scale bar, 1 µm). Lower panel, enlargement of the rectangle in the upper panel; arrows indicate co-localization of SRC3 and PSD95; scale bar, 200 nm).

To examine the distribution of SRC3 in a more direct way, we performed immunofluorescent (IF) assay in the mouse CA1 region. SRC3 was strongly expressed in the cytoplasm in addition to the nucleus (Fig. 1C), consistent with the results of Western blotting (Fig. 1A). To visualize the expression of SRC3 in the Pre and PSD, we performed IF assays using STED microscopy. In agreement with the results from subcellular fractionation, SRC3 was expressed in the PSD (Fig. 1D), suggesting that SRC3 regulates synaptic function.

Normal Glutamatergic Transmission at the Schaffer Collateral (SC)-CA1 Synapse in Src3 +/− Mice

To investigate the function of SRC3 in the synapse, we characterized Src3 mutant mice in which a cassette containing lacZ is inserted into the Src3 gene [6]. Because the Src3-null mutation causes overall growth retardation and partial lethality [6], we focused on Src3+/− mice that were normal in body and brain weights and did not display global morphological deficits in the hippocampus (Fig. 2A–D). However, the SRC3 protein levels were reduced to about half in the hippocampus of Src3+/− mice compared with wild-type (WT) littermates (Fig. 2E). β-Gal, which is expressed under the promoter of the Src3 gene, was high in the stratum pyramidale layer of the hippocampus where the somata of pyramidal neurons are enriched (Fig. 2F), in agreement with a previous report [6].

Normal development of Src3+/− mice. A Images (left) and quantification (right) of body weight of 2-month-old Src3+/− and WT mice (NS, not significant, two-sided t-test; n = 12/group; mean ± SEM; scale bar, 2.5 mm0. B Images (left) and quantification (right) of brain weight of 2-month-old Src3+/− and WT mice (NS, not significant, two-sided t-test, n = 6/group; mean ± SEM; scale bar, 5 mm). C, D Hippocampal slices from 2-month-old WT (C) and Src3+/− mice (D) stained with anti-NeuN (pink) and DAPI (blue) showing intact global morphology in Src3+/− mice (scale bar, 400 µm). E, Representative blots (left) and quantification (right) of SRC3 protein/α-tubulin levels in hippocampi from Src3+/− and WT mice (n = 6/group; mean ± SEM normalized to WT; ***P <0.001, two-sided t-test). F Representative image of β-gal activity in a 2-month-old Src3+/− hippocampus (scale bar, 400 µm).

We first studied whether Src3+/− mutation affects dendritic arborization in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. To this end, we filled the neurons with biocytin during electrophysiological recording and used immunofluorescence to reveal the dendritic morphology (Fig. 3A). The extent of dendrite arborization was quantified by Sholl analysis (Fig. 3B). The arborization of basal and apical dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons was similar in the WT and Src3+/− mice (Fig. 3C, D), which suggest that Src3+/− mutation does not affect dendritic development.

Intact basal glutamatergic transmission in CA1 pyramidal neurons from Src3+/− hippocampus. A Dendritic morphology of a CA1 pyramidal neuron from a 2-month-old WT mouse; the neuron was filled with biocytin during recording and later fixed and immunostained with anti-biocytin antibodies (scale bar, 200 µm). B Diagram for Sholl analysis of the neuron in A (scale bar, 300 µm). C Basal dendritic arborization of CA1 pyramidal neurons is not altered in Src3+/− mice (n = 10 cells from 4 WT mice, n = 13 cells from 4 Src3+/− mice; mean ± SEM; Genotype F(1, 21) = 0.0000118, P = 0.9973, two-way ANOVA). D Apical dendritic arborization of CA1 pyramidal neurons is not altered in Src3+/− mice (n = 10 cells from 4 WT mice, n = 13 cells from 4 Src3+/− mice, mean ± SEM; Genotype F(1, 21) = 0.1046, P = 0.7496, two-way ANOVA). E Representative sEPSCs in CA1 pyramidal neurons from WT and Src3+/− mice. F Similar cumulative plots of sEPSC frequency (left) and amplitude (right) in CA1 pyramidal neurons from WT and Src3+/− mice (quantification in inserts; n = 16 cells from 4 WT mice, n = 18 cells from 4 Src3+/− mice; mean ± SEM; NS, not significant, two-sided t-test. G Representative traces (upper) and quantification (lower) showing similar paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) at SC-CA1 synapses in WT and Src3+/− mice (n = 12 slices from 4 WT mice, n = 9 slices from 4 Src3+/− mice; mean ± SEM; Genotype F(1, 95) = 3.271, P = 0.0737, two-way ANOVA). H Representative action potentials in CA1 pyramidal neurons from WT (upper) and Src3+/− (lower) mice. I I/O curves of CA1 pyramidal neurons showing comparable excitability of CA1 pyramidal neurons in WT and Src3+/− mice (n = 15 cells from 4 WT mice, n = 19 cells from 4 Src3+/− mice; mean ± SEM; Genotype F(1, 32) = 0.1999, P = 0.6578, two-way ANOVA.

To study whether Src3+/− mutation alters glutamatergic transmission, we used whole-cell patch clamp to record spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs) in CA1 pyramidal neurons. As shown in Fig. 3E and F, both the frequency and amplitude of sEPSCs were comparable in the WT and Src3+/− mice, indicating that glutamatergic transmission is normal in Src3+/− mice. Consistent with this result, the probability of glutamate release indicated by paired-pulse facilitation at SC-CA1 synapses was not altered in Src3+/− mice (Fig. 3G). Likewise, the excitability of CA1 pyramidal neurons was also normal in Src3+/− mice (Fig. 3H, I). Taken together, these results indicate that glutamatergic transmission is not altered by Src3+/− mutation.

An Important Role of SRC3 in Synaptic Plasticity

Next, we investigated whether Src3+/− mutation affects synaptic plasticity. The N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR)-dependent LTP at the SC-CA1 synapse is one of the most common forms of synaptic plasticity [30,31,32]. We recorded theta burst stimulation (TBS)-induced LTP at the SC-CA1 synapse from WT and Src3+/− hippocampal slices (Fig. 4A). Remarkably, TBS-elicited LTP at SC-CA1 synapses was impaired in Src3+/− mice compared with WT littermates (Fig. 4B, C), indicating an important role of SRC3 for LTP. SRC3 has a RID domain that interacts with the steroid hormone receptor and a KAT domain that exhibits lysine acetyltransferase activity [24]. To further determine whether the RID or KAT domain of SRC3 can rescue the LTP deficit in Src3+/− mice, we generated AAVs that expressed GFP or GFP plus a Flag-tagged RID or KAT domain of SRC3 (Fig. 4D). We delivered the AAV by stereotaxic injection into the hippocampus of 5-week-old Src3+/− mice, and 3 weeks later the EGFP and Flag-tagged proteins were detected in the hippocampus (Fig. 4E, F). The TBS-induced LTP at the SC-CA1 synapse was recorded from Src3+/− mice after hippocampal injection of AAV (Fig. 4G). Intriguingly, the LTP deficit in Src3+/− hippocampal slices was rescued by the KAT domain, but not the RID of SRC3 (Fig. 4H, I), suggesting that the KAT domain but not the RID of SRC3 is important for LTP.

Importance of SRC3 in LTP at the SC-CA1 synapse. A Diagram of fEPSP recording at SC-CA1 synapses from WT and Src3+/− mice. B Normalized fEPSP amplitude versus time (1-min intervals) for WT and Src3+/− hippocampal slices. C Quantification of data as in B showing reduced LTP in Src3+/− slices compared with control slices (n = 9 slices from 5 WT mice, n = 11 slices from 5 Src3+/− mice; mean ± SEM; **P = 0.0066, two-sided t-test). D Upper, schematic of AAV construct expressing EGFP-P2A-hSrc3 KAT/RID-3FLAG (SYN, human synapsin 1 promoter. Lower, diagram of stereotaxic injection of AAV into the hippocampus of the Src3+/− mouse. E Expression of EGFP in the hippocampus 3 weeks after AAV injection (scale bar, 400 µm). F Expression of Flag, SRC3, and α-tubulin in the hippocampus 3 weeks after AAV injection. G Diagram of fEPSP recording at SC-CA1 synapses in the Src3+/− hippocampus infected by AAV as in panel D. H Normalized fEPSP amplitude versus time (1-min intervals) in hippocampal slices infected by the indicated AAV. I Quantification of data as in H showing that the KAT domain but not the RID of SRC3 rescues the LTP deficit in Src3+/− mice (n = 11 slices from 5 Src3+/− mice overexpressing GFP, n = 12 slices from 6 Src3+/− mice overexpressing SRC3-KAT, n = 9 slices from 5 Src3+/− mice overexpressing SRC3-RID; mean ± SEM; NS, not significant, ***P = 0.0007, one-way ANOVA vs GFP group).

Alteration of NMDAR Subunits in the Hippocampus of Src3 +/− Mice

Next, we investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying the LTP deficit in Src3+/− mice. The NMDAR-dependent AMPAR (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor) trafficking is considered the most important mechanism for LTP [33]. For this reason, we investigated whether the synaptic distribution of NMDARs or AMPARs is altered in Src3+/− mice. We purified the PSD fraction from WT and Src3+/− hippocampi and performed Western blots on their lysates. As shown in Fig. 5A and B, the NR2A subunit of the NMDAR was higher in the PSD fraction from the Src3+/− hippocampus than in controls. In contrast, the NR2B subunit of the NMDAR was lower in the PSD fraction from the Src3+/− hippocampus than in WT littermates (Fig. 5A, C). We did not find any difference in the PSD distribution of the AMPAR subunits GluR1 and GluR2 between the WT and Src3+/− hippocampus (Fig. 5A, D, E). The SRC3 protein levels were reduced by half in the hippocampus of Src3+/− mice compared with WT littermates (Fig. 5A, F). Given that the NR2B subunit of the NMDAR is required for LTP while the NR2A subunit inhibits LTP [34], our results suggest that the alteration of NMDAR subunits in the PSD fraction are responsible for the LTP deficits in the Src3+/− hippocampus. In support of this hypothesis was the finding that activation of CaMKIIα, a protein kinase critical for LTP and downstream of NMDARs, was impaired after chemical LTP stimulation in Src3+/− hippocampal slices compared with control slices (Fig. 5G, H). Altogether, these data suggest that abnormal composition of NMDAR subunits in the PSD region accounts for the LTP deficit in the hippocampus of Src3+/− mice.

Alteration of NMDAR subunits in the PSD of the Src3+/− hippocampus. A Western blots showing increased NR2A subunits but decreased NR2B subunits of NMDARs in the PSD of the Src3+/− hippocampus, compared with the WT hippocampus. B Quantification of NR2A/PSD95 as in panel A (n = 6/group; mean ± SEM; ***P <0.001, two-sided t-test). C Quantification of NR2B/PSD95 as in panel A (n = 6/group; mean ± SEM; ***P = 0.0003). D Quantification of GluR1/PSD95 as in panel A (n = 6/group; mean ± SEM; NS, not significant, two-sided t-test. E Quantification of GluR2/PSD95 as in panel A (n = 6/group; mean ± SEM; NS, not significant, two-sided t-test). F Quantification of SRC3 protein as in panel A s normalized to the WT showing reduced levels in the hippocampus from Src3+/− mice (n = 6/group; mean ± SEM; ***P <0.001, two-sided t-test). G Western blots showing reduced cLTP-induced CaMKIIα activation in Src3+/− slices, compared with WT slices. H Quantification of p-CaMKIIα/CaMKIIα normalized to WT slices under control conditions as in panel G (n = 6; mean ± SEM; NS, not significant, ***P <0.001, one-way ANOVA.

Importance of SRC3 in Hippocampus-dependent Learning and Memory

LTP at SC-CA1 synapses is coupled to hippocampus-dependent learning and memory [21, 35,36,37,38], thus we next investigated whether SRC3 is important for these processes. No difference was found between WT and Src3+/− mice in locomotor activity in the open field (Fig. 6A), indicating no deficits in the locomotion of these mice. The time spent in the center and margin of the open field was also similar in WT and Src3+/− mice (Fig. 6B), suggesting no anxiety-like behavior in these mice.

A critical role of SRC3 in novel object recognition (NOR). A Distance travelled during the first 30 min in the open field by WT and Src3+/− mice (n = 16/group; mean ± SEM; Genotype F(1, 30) = 0.4119, P = 0.5259). B Time spent in the center and margin of the open field during the first 5 min by WT and Src3+/− mice (n = 16/group; mean ± SEM; NS, not significant, two-sided t-test. C Occupancy plot of the heads of WT and Src3+/− mice around a novel (N) and a familiar (F) object. D Total exploration time with N and F in WT and Src3+/− mice (n = 15/group; mean ± SEM; NS, not significant, two-sided t-test. E Discrimination indexes showing impaired NOR in Src3+/− mice (n = 15/group; mean ± SEM; *P = 0.0218, two-sided t-test. F Occupancy plot of the heads of Src3+/− mice receiving different AAV treatment around a novel (N) and a familiar (F) object. G Total exploration time with N and F in Src3+/− mice receiving different AAV treatments (n = 15/group; mean ± SEM; NS, not significant, one-way ANOVA. H Discrimination index showing the KAT domain but not the RID of SRC3 rescues the NOR deficit of Src3+/− mice (n = 15/group; mean ± SEM; NS, not significant, **P = 0.0017, one-way ANOVA vs GFP group).

Next, we studied whether SRC3 is important for novel object recognition (NOR), a paradigm for investigating hippocampus-dependent short-term memory [39]. Although the total exploration time around novel and familiar subjects was similar in the WT and Src3+/− mice (Fig. 6C, D), the discrimination index was significantly lower in the Src3+/− mice than in WT littermates (Fig. 6C, E). These results suggest that SRC3 is important for NOR. To address whether the KAT or RID domain of SRC3 is critical for NOR, we delivered AAVs expressing GFP, KAT, or RID of SRC3 by stereotaxic injection into the hippocampus of 5-week-old Src3+/− mice. Strikingly, 3 weeks later, the NOR deficit in Src3+/− mice was rescued by the AAV expressing KAT but not that expressing RID (Fig. 6F–H), similar to the rescue of LTP (Fig. 4G–I). These data indicate that SRC3 regulates NOR through the KAT domain.

Lastly, we investigated whether SRC3 is important for hippocampus-dependent spatial memory in the Morris water maze [40, 41]. Although the swimming speed was similar in WT and Src3+/− mice (Fig. 7A), the learning process was slower in Src3+/− mice than in WT littermates (Fig. 7B). During probe tests, the time spent in the target area and the number of platform crossings were significantly lower in Src3+/− mice than in WT littermates (Fig. 7C–E). These results indicate that SRC3 is important for hippocampus-dependent spatial memory. Remarkably, the water-maze deficits in Src3+/− mice were rescued by the hippocampal injection of AAVs expressing the KAT domain but not RID of SRC3 (Fig. 7F–J), similar to the rescue of NOR (Fig. 6F–H). Taken together, these results demonstrate that SRC3 is important for hippocampus-dependent learning and memory.

Importance of SRC3 in spatial memory in the Morris water maze (MWM). A Swimming speeds in WT and Src3+/− mice (n = 18/group; mean ± SEM; NS, not significant, two-sided t-test). B Learning curves in Src3+/− and WT mice during training (n = 18/group; mean ± SEM; **Genotype F(1, 170) = 8.842, P = 0.0041, two-way ANOVA, Tar, target quadrant; Opp, opposite quadrant; Lef, left quadrant; Rig, right quadrant). C Swimming traces of WT and Src3+/− mice during probe tests. D Times spent in the target quadrant by Src3+/− and WT mice (n = 18/group; mean ± SEM; *P = 0.0216, two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test). E Platform crossings in the Src3+/− and WT mice during probe tests (n = 18/group; mean ± SEM; **P = 0.0064, two-sided t-test). F Swimming speeds in Src3+/− mice receiving indicated AAV treatment (n = 18/group; mean ± SEM; NS, not significant, one-way ANOVA). G Time to platform showing the KAT domain but not the RID of SRC3 rescues the learning deficit of Src3+/− mice (n = 15/group; mean ± SEM; ***Genotype F(2, 225) = 11.23, P <0.001, two-way ANOVA). H Swimming traces of Src3+/− mice receiving different AAV treatment during probe tests. I Time spent in the target quadrant during probe tests showing the KAT domain but not the RID of SRC3 rescues the memory deficit of Src3+/− mice (n = 18/group; mean ± SEM; *P = 0.0283, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test). J Numbers of platform-crossings during probe tests showing that the KAT domain but not the RID of SRC3 rescues the memory deficit of Src3+/− mice (n = 18/group; mean ± SEM; NS, not significant, *P = 0.0218, one-way ANOVA vs GFP group).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated a previously unknown function of SRC3 in regulating synaptic plasticity and hippocampus-dependent learning and memory. SRC3 is known to be expressed in the brain; however, its function in the brain is largely unknown. We showed here that Src3 mRNA is enriched in the pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus, in agreement with a previous report [6] and data from the Allen Brain Institute (https://mouse.brain-map.org/). An early study reported that female but not male Src3 mutant mice show increased anxiety in the open field test [42], consistent with our finding. Although a previous study indicated that knockdown of SRC3 by shRNA increases dendritic arborization in cultured hippocampal neurons [43], our results suggested that dendritic arborization is not altered in the CA1 pyramidal neurons of Src3+/− mice. The discrepancy between these two studies might be a result of the different approaches to down-regulating SRC3 (shRNA versus heterozygous mutation), or the different conditions in vitro and in vivo.

SRC3 is critically involved in the classical genomic signaling of steroid hormones [24]. On the other hand, steroid hormones can act in a non-classical manner through receptors on the cell membrane [44]. We showed here that SRC3 is strongly expressed in the cytoplasm and synapses, in addition to the nucleus in the mouse hippocampus. These findings suggest that SRC3 may regulate both the genomic and non-genomic signaling pathways of steroid hormones. The synaptic distribution of NMDAR subunits and the downstream kinase activation were impaired in Src3+/− mice, suggesting crosstalk between steroid hormone signaling and NMDAR expression or function. In support of this hypothesis are previous studies showing that steroid hormones such as estrogen and progesterone regulate the expression or function of NMDARs in the brain [45,46,47].

Src3−/− mice exhibit growth retardation while Src3+/− mice show the same growth rate as WT littermates [6]. The exact reasons why Src3+/− mice have a normal body weight and length are not clear. The SRC family of proteins (SRC1, SRC2, and SRC3) are all expressed in the nucleus to regulate gene expression. We speculate that half of SRC3 protein level might be sufficient for the regulation of gene expression required for body growth, along with compensation by SRC1 or SRC2.

We also demonstrated that the KAT domain rather than the RID of SRC3 is critical for regulating synaptic plasticity and memory. The RID of SRC3 contains three LXXLL (X represents any amino-acid) motifs, which form amphipathic α-helices and are responsible for binding with nuclear receptors [24]. The KAT domain is localized in the C terminus of SRC3 and exhibits histone acetyltransferase activity [48], although its cellular substrates are incompletely identified.

Our results support the importance of the lysine acetyltransferase activity of SRC3 in regulating brain functions. Apart from histone proteins in the nucleus, the substrates of SRC3 in the brain remain largely unknown. Given that SRC3 is expressed in the cytoplasm and synapses, it is possible that SRC3 may acetylate cytoplasmic or synaptic proteins. Recent studies indicate that Src3 is genetically linked with some neurodegenerative disorders such as multiple sclerosis and hearing loss [49, 50]. Future work is required to address how dysregulation of Src3 leads to brain disorders.

References

McEwen BS. Steroid hormones: Effect on brain development and function. Horm Res 1992, 37: 1–10.

Yamamoto KR, Alberts BM. Steroid receptors: Elements for modulation of eukaryotic transcription. Annu Rev Biochem 1976, 45: 721–746.

Levin ER, Hammes SR. Nuclear receptors outside the nucleus: Extranuclear signalling by steroid receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016, 17: 783–797.

Yu C, York B, Wang S, Feng Q, Xu J, O’Malley BW. An essential function of the SRC-3 coactivator in suppression of cytokine mRNA translation and inflammatory response. Mol Cell 2007, 25: 765–778.

Suen CS, Berrodin TJ, Mastroeni R, Cheskis BJ, Lyttle CR, Frail DE. A transcriptional coactivator, steroid receptor coactivator-3, selectively augments steroid receptor transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem 1998, 273: 27645–27653.

Xu J, Liao L, Ning G, Yoshida-Komiya H, Deng C, O’Malley BW. The steroid receptor coactivator SRC-3 (p/CIP/RAC3/AIB1/ACTR/TRAM-1) is required for normal growth, puberty, female reproductive function, and mammary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97: 6379–6384.

Louie MC, Zou JX, Rabinovich A, Chen HW. ACTR/AIB1 functions as an E2F1 coactivator to promote breast cancer cell proliferation and antiestrogen resistance. Mol Cell Biol 2004, 24: 5157–5171.

Liu Z, Liao L, Zhou S, Xu J. Generation and validation of a mouse line with a floxed SRC-3/AIB1 allele for conditional knockout. Int J Biol Sci 2008, 4: 202–207.

Wu Z, Yang M, Liu H, Guo H, Wang Y, Cheng H. Role of nuclear receptor coactivator 3 (Ncoa3) in pluripotency maintenance. J Biol Chem 2012, 287: 38295–38304.

Chen W, Lu X, Chen Y, Li M, Mo P, Tong Z, et al. Steroid receptor coactivator 3 contributes to host defense against enteric bacteria by recruiting neutrophils via upregulation of CXCL2 expression. J Immunol 2017, 198: 1606–1615.

Tetel MJ, Acharya KD. Nuclear receptor coactivators: Regulators of steroid action in brain and behaviour. J Neuroendocrinol 2013, 25: 1209–1218.

Chen X, Liu Z, Xu J. The cooperative function of nuclear receptor coactivator 1 (NCOA1) and NCOA3 in placental development and embryo survival. Mol Endocrinol 2010, 24: 1917–1934.

Zhou HJ, Yan J, Luo WP, Ayala G, Lin SH, Erdem H, et al. SRC-3 is required for prostate cancer cell proliferation and survival. Cancer Res 2005, 65: 7976–7983.

Zhou XE, Suino-Powell KM, Li J, He Y, Mackeigan JP, Melcher K, et al. Identification of SRC3/AIB1 as a preferred coactivator for hormone-activated androgen receptor. J Biol Chem 2010, 285: 9161–9171.

Nishihara E, Yoshida-Komiya H, Chan CS, Liao L, Davis RL, O’Malley BW, et al. SRC-1 null mice exhibit moderate motor dysfunction and delayed development of cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurosci 2003, 23: 213–222.

Yore MA, Im D, Webb LK, Zhao Y, Chadwick JG, Molenda-Figueira HA, et al. Steroid receptor coactivator-2 expression in brain and physical associations with steroid receptors. Neuroscience 2010, 169: 1017–1028.

Auger AP, Tetel MJ, McCarthy MM. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1) mediates the development of sex-specific brain morphology and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97: 7551–7555.

Molenda-Figueira HA, Williams CA, Griffin AL, Rutledge EM, Blaustein JD, Tetel MJ. Nuclear receptor coactivators function in estrogen receptor- and progestin receptor-dependent aspects of sexual behavior in female rats. Horm Behav 2006, 50: 383–392.

Yang Y, van der Klaauw AA, Zhu L, Cacciottolo TM, He Y, Stadler LKJ, et al. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 modulates the function of Pomc neurons and energy homeostasis. Nat Commun 2019, 10: 1718.

Stashi E, Lanz RB, Mao J, Michailidis G, Zhu B, Kettner NM, et al. SRC-2 is an essential coactivator for orchestrating metabolism and circadian rhythm. Cell Rep 2014, 6: 633–645.

Bian C, Huang Y, Zhu H, Zhao Y, Zhao J, Zhang J. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 knockdown decreases synaptic plasticity and impairs spatial memory in the Hippocampus of mice. Neuroscience 2018, 377: 114–125.

Zhou W, He Y, Rehman AU, Kong Y, Hong S, Ding G, et al. Loss of function of NCOR1 and NCOR2 impairs memory through a novel GABAergic hypothalamus-CA3 projection. Nat Neurosci 2019, 22: 205–217.

Sun Z, Xu Y. Nuclear receptor coactivators (NCOAs) and corepressors (NCORs) in the brain. Endocrinology 2020, 161: bqaa083.

Xu J, Wu RC, O’Malley BW. Normal and cancer-related functions of the p160 steroid receptor co-activator (SRC) family. Nat Rev Cancer 2009, 9: 615–630.

Yin DM, Chen YJ, Lu YS, Bean JC, Sathyamurthy A, Shen C, et al. Reversal of behavioral deficits and synaptic dysfunction in mice overexpressing neuregulin 1. Neuron 2013, 78: 644–657.

Liu JH, Li ZL, Liu YS, Chu HD, Hu NY, Wu DY, et al. Astrocytic GABAB receptors in mouse Hippocampus control responses to behavioral challenges through astrocytic BDNF. Neurosci Bull 2020, 36: 705–718.

Otmakhov N, Khibnik L, Otmakhova N, Carpenter S, Riahi S, Asrican B, et al. Forskolin-induced LTP in the CA1 hippocampal region is NMDA receptor dependent. J Neurophysiol 2004, 91: 1955–1962.

West PJ, Saunders GW, Remigio GJ, Wilcox KS, White HS. Antiseizure drugs differentially modulate theta-burst induced long-term potentiation in C57BL/6 mice. Epilepsia 2014, 55: 214–223.

Kouvaros S, Papatheodoropoulos C. Theta burst stimulation-induced LTP: Differences and similarities between the dorsal and ventral CA1 hippocampal synapses. Hippocampus 2016, 26: 1542–1559.

Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: Long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature 1993, 361: 31–39.

Huganir RL, Nicoll RA. AMPARs and synaptic plasticity: The last 25 years. Neuron 2013, 80: 704–717.

Malenka RC, Bear MF. LTP and LTD: An embarrassment of riches. Neuron 2004, 44: 5–21.

Shi SH, Hayashi Y, Petralia RS, Zaman SH, Wenthold RJ, Svoboda K, et al. Rapid spine delivery and redistribution of AMPA receptors after synaptic NMDA receptor activation. Science 1999, 284: 1811–1816.

Foster KA, McLaughlin N, Edbauer D, Phillips M, Bolton A, Constantine-Paton M, et al. Distinct roles of NR2A and NR2B cytoplasmic tails in long-term potentiation. J Neurosci 2010, 30: 2676–2685.

Baudry M, Zhu G, Liu Y, Wang Y, Briz V, Bi X. Multiple cellular cascades participate in long-term potentiation and in hippocampus-dependent learning. Brain Res 2015, 1621: 73–81.

Liu JH, You QL, Wei MD, Wang Q, Luo ZY, Lin S, et al. Social isolation during adolescence strengthens retention of fear memories and facilitates induction of late-phase long-term potentiation. Mol Neurobiol 2015, 52: 1421–1429.

Wang SL, Sheng T, Ren SQ, Tian T, Lu W. Distinct roles of PKCι/λ and PKMζ in the initiation and maintenance of hippocampal long-term potentiation and memory. Cell Rep 2016, 16: 1954–1961.

Kojima N, Yasuda H, Hanamura K, Ishizuka Y, Sekino Y, Shirao T. Drebrin A regulates hippocampal LTP and Hippocampus-dependent fear learning in adult mice. Neuroscience 2016, 324: 218–226.

Goh JJ, Manahan-Vaughan D. Role of inhibitory autophosphorylation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (αCAMKII) in persistent (>24 h) hippocampal LTP and in LTD facilitated by novel object-place learning and recognition in mice. Behav Brain Res 2015, 285: 79–88.

Morris R. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J Neurosci Methods 1984, 11: 47–60.

Zhang PA, Sun Q, Li YC, Weng RX, Wu R, Zhang HH, et al. Overexpression of purinergic P2X4 receptors in hippocampus rescues memory impairment in rats with type 2 diabetes. Neurosci Bull 2020, 36: 719–732.

Stashi E, Wang L, Mani SK, York B, O’Malley BW. Research resource: Loss of the steroid receptor coactivators confers neurobehavioral consequences. Mol Endocrinol 2013, 27: 1776–1787.

Störchel PH, Thümmler J, Siegel G, Aksoy-Aksel A, Zampa F, Sumer S, et al. A large-scale functional screen identifies Nova1 and Ncoa3 as regulators of neuronal miRNA function. EMBO J 2015, 34: 2237–2254.

Simoncini T, Genazzani AR. Non-genomic actions of sex steroid hormones. Eur J Endocrinol 2003, 148: 281–292.

Cyr M, Ghribi O, Thibault C, Morissette M, Landry M, Di Paolo T. Ovarian steroids and selective estrogen receptor modulators activity on rat brain NMDA and AMPA receptors. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2001, 37: 153–161.

Tameh AA, Karimian M, Zare-Dehghanani Z, Aftabi Y, Beyer C. Role of steroid therapy after ischemic stroke by n-methyl-d-aspartate receptor gene regulation. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2018, 27: 3066–3075.

Waters EM, Mazid S, Dodos M, Puri R, Janssen WG, Morrison JH, et al. Effects of estrogen and aging on synaptic morphology and distribution of phosphorylated Tyr1472 NR2B in the female rat hippocampus. Neurobiol Aging 2019, 73: 200–210.

Chen HW, Lin RJ, Schiltz RL, Chakravarti D, Nash A, Nagy L, et al. Nuclear receptor coactivator ACTR is a novel histone acetyltransferase and forms a multimeric activation complex with P/CAF and CBP/p300. Cell 1997, 90: 569–580.

Vilariño-Güell C, Zimprich A, Martinelli-Boneschi F, Herculano B, Wang Z, Matesanz F, et al. Exome sequencing in multiple sclerosis families identifies 12 candidate genes and nominates biological pathways for the genesis of disease. PLoS Genet 2019, 15: e1008180.

da Silva RS, Dantas VLG, Alves LU, Batissoco AC, Oiticica J, Lawrence EA, et al. NCOA3 identified as a new candidate to explain autosomal dominant progressive hearing loss. Hum Mol Genet 2021, 29: 3691–3705.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970900), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and the Program for Special Appointment Professors (Eastern Scholars) at Shanghai Institutions of Higher Learning.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, HL., Zhao, B., Yang, P. et al. Steroid Receptor Coactivator 3 Regulates Synaptic Plasticity and Hippocampus-dependent Memory. Neurosci. Bull. 37, 1645–1657 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-021-00741-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-021-00741-5