Abstract

Family factors are central both for adolescent development in general and for the development of delinquency. For female delinquency they appear to be particularly important. The aim of this study was to explore family-related statements in adolescent females’ delinquency narratives from a developmental perspective. Interviews with nine female adolescent offenders were analysed using consensual qualitative research (CQR). The main findings consisted of five themes concerning the family in relation to the participants’ delinquency. In the delinquency narratives, families were described as being involved in the entire process of delinquency. Urges both for proximity and distance in family relations were expressed in the narratives. Delinquency was also found to be related to transactions between participants and their families. Our findings indicate that the developmental perspective on family factors for females with limited delinquency is a meaningful way to further investigate this group of offenders. Furthermore, this perspective could in the long-term also potentially contribute to the design of adequate community-based measures for this yet under-researched group of young offenders.

Similar content being viewed by others

For both females and males, problem behaviours in general, and delinquency in particular, increase and peak during adolescence (Piquero, Diamond, Jennings, & Reingle, 2013). Delinquency is defined as a minor person or a nonadult, most often an adolescent, engaging in illegal behaviour or criminal activities (Estrada & Flyghed, 2017). In most cases, criminal behaviour can be regarded as a transitional developmental process, serving the purposes of emancipation and achievement of respect and independence (Bonnie, Johnson, Chemers, & Schuck, 2013; Laub & Sampson, 2001; Moffitt, 2006). There is limited research on this group of offenders (e.g., Kang, 2019). Available studies indicate however, that also young offenders with limited delinquency may be at risk of suboptimal development (Andersson, Levander, & Torstensson Levander, 2013; Nilsson & Estrada, 2009; Odgers et al., 2008; Roisman, Monahan, Campbell, Steinberg, & Cauffman, 2010). Independent of the long-term outcome, the increased levels of risk behaviour in adolescence coincide with parents having to gradually reduce their control and power in favour of adolescent autonomy and independence (Keijsers & Poulin, 2013). During childhood, no other developmental period comes with such a remarkable or rapid transformation as adolescence, and even for the most well-functioning families, this is a phase that challenges emotional resources (Steinberg & Silk, 2002).

Family factors have been regarded as key components for limiting the risk of involvement in criminality by several theories, for example, life-course developmental theories (e.g., Moffitt, 1993; Patterson & Yoerger, 2002), as well as social control theory (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990). The association between family factors and delinquency is also empirically supported. The results from both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that antisocial behaviour within the family (i.e., familial criminality, drug use, abuse) as well as inconsistent and harsh parenting are associated with criminal behaviour (e.g., Hoeve et al., 2009; Pardini, Waller, & Hawes, 2015). In contrast, attachment and bonding seem to be relevant protective factors (Hoeve et al., 2009; Pardini et al., 2015). Also, to what extent parents monitor their children, convey that delinquency is unacceptable, reward good behaviour and reprimand misbehaviour has been argued to reduce the likelihood of adolescent offending. How effective parental monitoring actually is in preventing problem behaviour has been a central issue in the scientific debate (Keijsers, 2016; Kerr, Stattin, & Burk, 2010; Stattin & Kerr, 2000). The development in this field of research has taken a direction where the reciprocal nature of interaction between parent and child, rather than the one-sided parental monitoring, has become increasingly emphasized (Kerr & Stattin, 2003; Walters, 2019). This suggests that not only parents affect their children but also children affect their parents, conceptualizing families as a transactional system. For female delinquents, family factors appear to be particularly important (Kroneman, Loeber, Hipwell, & Koot, 2009; Kruttschnitt & Giordano, 2009). Even if family-related factors are well established to be associated with delinquency, research has not yet provided any clear answers on this topic or on how parents can act preventively (Keijser, 2016). Whereas numerous cross-sectional studies (e.g., Hoeve et al., 2009; Pardini et al., 2015) have documented different risk factors related to female delinquency, only a small number of studies have investigated young offenders’ own perspective on their interpersonal relationships. However, most of these studies include only a small number or no females at all (e.g., Sander, Sharkey, Olivarri, Tanigawa, & Mauseth, 2010; Wester, MacDonald, & Lewis, 2008). Those who do include young female offenders have mostly focused on victimization and its potential connection to the young female’s delinquent behaviour and/or sampled incarcerated adolescents (e.g., Gaarder & Belknap, 2004; Herrman & Silverstein, 2012). To our knowledge the present study is one of the few studies to examine how adolescent females themselves understand and make sense of their delinquent behaviour and in particular how different risk factors such as family are, in their own perspective, related to their delinquent behaviour.

A Developmental Approach to Delinquency

A developmental approach to delinquency acknowledges adolescent offending as occurring in the context of a period of life where individuals tend to exercise poor judgment and take risks, which in turn can result in higher frequencies of offending. Delinquent behaviours during adolescence have been regarded as evolving from a normative endeavour to establish independence and from the development of identity (Barbot & Hunter, 2012; Moffitt, 1993). It has been suggested that most delinquent adolescents desist from offending merely as a result of maturation, even if timing and trajectories of desistance varies (Laub & Sampson, 2001). Desistance in delinquents has also been considered as a part of the transition to adulthood. One way which this transition is assumed to be achieved by is the development of identity. The presumption is that the occurrence of change in delinquency is a result of a successful transition into adulthood where the continued criminal activity becomes incompatible with a mature identity (Massoglia & Uggen, 2010). Female offenders are less underrepresented in the group of offenders where the offending is a part of a normative development and limited to adolescence, than among offenders with more pronounced behavioural problems that are at risk of life long criminality (Odgers et al., 2008).

As mentioned previously only limited research has sampled this group of offenders (Andersson et al., 2013; Nilsson & Estrada, 2009; Odgers et al., 2008; Roisman et al., 2010). The results from these studies indicate that although these individuals do not display persistent criminality in adulthood, they do have other difficulties in life (Nilsson & Estrada, 2009; Odgers et al., 2008). For example, longitudinal studies conducted on females with adolescent limited offending indicate adjustment problems across multiple dimensions in adulthood, including mental health, substance dependence and educational deficits (Moffitt, 2001; Odgers et al., 2008; Roisman et al., 2010). On the other hand, other studies have found contradictory results, where a longitudinal study on a Swedish sample of female offenders showed that the adolescent limited group was quite similar to the females in the non-criminal group after entering adulthood (Andersson, Levander, Svensson, & Torstensson Levander 2012; Andersson et al., 2013). Given these inconclusive findings, and the lack of qualitative studies in particular, there is a need for further research on adolescent offenders where the behaviour can be regarded as a part of a normative development (Piquero et al., 2013). Although the majority of adolescents who commit crimes, have limited delinquency where their offences leads to non-custodial sanction, the emerging knowledge base is mostly limited.

Adolescents with Limited Delinquency: The Current Project

The present study is part of a research project in which the primary focus lies on research questions regarding offenders with limited delinquency who do not exhibit pronounced behavioural problems. Within this project studies based on samples of convicted Swedish youths receiving community-based measures have been conducted (Ginner Hau, 2010; Ginner Hau & Smedler, 2011a, b) indicating a need to further investigate this group of young offenders. Adolescent female offenders have been a priority, and to date we have conducted three studies focusing females with limited delinquency (Azad, Ginner Hau, & Karlsson 2017; Azad & Ginner Hau, 2018, 2020). Two of these studies (Azad & Ginner Hau, 2018, 2020) were focused on female offenders (n = 144) in a sample of Swedish youths sentenced to community service (total n = 938). In both studies, no pronounced behavioural problems were depicted, but the educational deficit that was identified indicated a possible risk for a deteriorating quality of life. In addition to these studies, the project also includes qualitative data from interviews with delinquent female adolescents. Qualitative research based on interviews with non-residential female offenders is more or less non-existent. Therefore, qualitative data collected in these interviews offer a possibility to identify valuable entry points for further research on this particular group of offenders. When the participants were allowed to tell their own delinquency narratives, two aspects appeared central: peers and family. The first study conducted on the data focused on the delinquency narratives concerning peers (Azad et al., 2017). The findings from this study indicated that from the female offenders’ perspectives, delinquent behaviour was regarded as a way to socialize and that pro-social and delinquent activities with peers seemed to serve similar developmental functions. Furthermore, the female offenders’ delinquency narratives showed awareness of the need to socialize with pro-social friends in order to refrain from delinquency. The present study focusses on the other central aspect of the interviews, i.e. the participants narratives concerning their families. From a developmental perspective, the social context of which the family is an important part, is an area that is particularly subject to change during adolescence (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Even so, the parents still serve as base of security in the exploration of the world outside the family (Peterson, 2005). The family context during adolescence also sets the stage for adulthood that lies just beyond (Kerig & Schultz, 2012). Exploration of the family-related challenges that female offenders with limited delinquency experience could offer a feasible way to build a deeper understanding of this under-researched group, which in turn can contribute to the support offered to these young females and their families.

Purpose

The overall purpose of this study is to contribute to the development of the understanding of young female offenders with limited delinquency by inductively explore family-related statements in adolescent females’ delinquency narratives from a developmental perspective. The overall research question formulated for the study was: How is family described and related to the delinquent behaviour in female adolescent offenders’ delinquency narratives?

Method

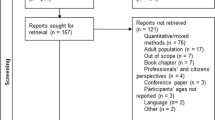

Participants were recruited from the part of the Swedish juvenile justice system that is presumed to deal with young offenders with limited delinquency, i.e. youth service. As the goal was to collect the participants perspective data was collected using semi-structured interviews. Consensual qualitative research (CQR) (Hill, 2012; Hill, Thompson, & Williams, 1997; Hill et al., 2005) was used for analysing the interviews. We chose this strategy for data analysis as it is well suited for an inductive approach and involves several researchers working together in a structured manner. We thus considered CQR to enable trustworthy results that captured the essence of the participants statements.

Participants

The participants included nine female offenders sentenced to youth service in two major Swedish cities. The interviewees were 15 - 21 years of age when interviewed but had committed the crimes they were convicted for at 15–17 years of age. Three of the participants reported that they were convicted for violent crimes, and five had been convicted for theft or shoplifting. For one participant, the crime was unclear, as she reported a felony that does not exist. The participant’s fictitious names, age and crime for which they are convicted of are presented in Table 1.

Two participants lived with both their parents and seven reported having separated parents. Five out of those seven reported living with single mothers or with their mothers and the mothers’ new partners, one lived with her boyfriend, one lived with relatives and one lived half the time with each parent. The participants had between one and six siblings.

Apart from the contact in connection to the interviews, described in the Procedure section, there were no interactions or relations between any member of the research team and the participants.

Procedure

In the Swedish juvenile justice system youth service is a penalty intended for young offenders under the age of 21. It is intended as a rehabilitative measure and consists of unpaid work, and a so-called advocacy program (Swedish Government, 2006). The advocacy program intends to meet the needs of this group of offenders and is specified in connection with the youth service sanction. Youth service has been an independent sanctioning since 2007 and has become one of the most common referrals for young offenders (Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention, 2019). Youths that are assessed as having limited “special care needs” are sentenced solely to youth service. If the social services identify “special care needs”, youth service is awarded in combination with youth care. Since the sanction was introduced the number of female young offenders assigned to youth service in Sweden has varied, in 2019 it was just over 200 (Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention, 2020).

In Sweden the social services are responsible for youth service. Social services are organized by 290 independent municipalities, of which the majority has less than 25,000 inhabitants. A convenience sampling in terms of from which municipalities participants were recruited was therefore necessary and the participants were recruited from two major cities. Participants were recruited during a period of 9 months. During data collection all female offenders enrolled in youth service programs in these two cities were given written information about the study through the social workers responsible for the implementation of the sentence. The information letter contained a short background of the study asking if the young female was interested in participating and if she agreed to be contacted by the researchers. A separate information letter was given to the parents. Those interested in participating provided their contact information to the social workers and were then contacted by the interviewer (second author). The researcher informed the potential participants about the study and asked for their consent to participate in the study. If the adolescent agreed to participate time and place for the interview were scheduled. Three individuals showed interest in participating but declined to participate when approached by the interviewer. Before the interview started the participants were given information that participation was voluntary and independent of their participation in the youth service or any contact with the social services, that the interview would be recorded and transcribed and that information such as the names of person or places would be omitted and/or changed in the transcriptions, and that data would be treated strictly confidential and not passed on to the police and the social services. The participants were also informed that they could interrupt their participation at any time during and after the interview and that they were free to decline to answer questions they experienced as uncomfortable. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the interview. The present study was approved by the Stockholm Regional Ethics Board (2012/1259-31). Parental consent is not always required for youths over the age of 15 in Sweden (in accordance with the Act Concerning the Ethical Review of Research Involving Humans, 2003, p. 460). With approval from the Regional Ethics Board in Stockholm, guardians were therefore not asked for consent but were informed about the study.

Interviews

The interviews took place in private rooms in local libraries or private rooms provided by the social workers. Data were collected using semi-structured interviews. The interviews focused on the participants’ attitudes and beliefs about their delinquent behaviour, their sentencing, the path leading to their delinquent behaviour and the future, this was also the purpose that was communicated to the participants. No specific questions regarding the family were included in the interview guide. However, since all participants mentioned their families on their own, follow-up questions concerning the family were included, although they differed somewhat between participants. One pilot interview was conducted with the first participant recruited. No major adjustments were needed, and the interview was thus included in the analysis. The interviews lasted 40–70 min and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcription also included contextual information, such as nonverbal sounds (e.g., laughs, sighs) as well as pauses in conversation and silence. Non-linguistic observations (e.g., facial expressions, body language and emotions) were not included. Information such as the names of person or places were omitted and/or changed in the transcriptions as well as in the write up of the study. The participants were offered a gift voucher of SEK 200 for their participation.

Data Coding and Analysis

Consensual qualitative research (CQR) (Hill, 2012; Hill et al., 1997, 2005) was used for analysing the interviews. In this method, several judges take part in the coding process and strive to reach consensus in the different steps. In addition, auditors check the work of the judges to reduce the effects of group think. The independent coding of several judges combined with systematic procedures for reaching consensus as well as the additional review of a researcher who did not participate in this process was considered as strengthening methodological integrity and thus promoting the trustworthiness of the results.

The Research Team

Five researchers constituted the primary team. Researcher A: first author, PhD and licensed psychologist and principal investigator of the research project. Researcher B: Second author, PhD student in psychology and a licensed high-school teacher in psychology. Researcher C: Female graduate student in psychology and research assistant. Researcher D: Male psychology-student. Researcher E: Male psychologist, psychotherapist and professor of clinical psychology. All of the researchers included had experience of working with similar research topics or had experience of working with young people with different type of psychological and/or behavioural problems. Within the research team there was also a profound knowledge of developmental psychology. The research team was constituted with the intention to deepen rather than broaden the areas of expertise. This did naturally limit the diversity of perspectives within the research team, but did on the other hand offer a deep and broad knowledge in areas relevant for the study’s purposes. The ages of team members ranged from 29 to 52 years (M = 36, SD = 10.34). All of the members read relevant litterateur on CQR (Hill, 2012; Hill et al., 1997, 2005) prior to analysis as well as exemplar studies (e.g., Diamond et al., 2011; Sander et al., 2010). The interviewer, Researcher B, had prior experience and training conducting general psychological interviews.

Analysis Process

Coding of domains (Hill, 2012): The first step included developing domains, based on all the material relating to the same area. Each judge read three interviews independently and categorised the raw material into an appropriate domain. Consensus was reached about the placement of text into different domains and the naming of each domain. Ten different domains were created, and one judge independently coded the rest of the interviews accordingly. No new domains emerged when coding the rest of the interviews. For this study, the data in the domain containing all material on the family were used, which was 24 percent of the total number of transcribed words.

Abstracting core ideas (Hill, 2012): The main focus of each domain was captured while still staying close to the data. The judges independently formulated core ideas for each domain. Consensus concerning the content and wording of the core idea was reached. Once consensus was reached, one of the judges wrote the core ideas for the remaining cases, and the rest of the team reviewed them and discussed them until reaching consensus.

Cross-analysis/identifying themes (Hill, 2012): The judges first independently looked for common patterns in the core ideas from all participants for the family domain and then developed themes that best captured these patterns. The judges then presented their themes to each other. The themes and the core ideas the themes contained were discussed until consensus was reached. For validation, the themes were double-checked with the raw material (i.e., the interviews with each participant). During this process we also controlled whether data saturation had been achieved, and all themes were assessed as saturated.

Auditing (Hill, 2012): The auditors took part in the process at three points during the coding process. The first point was after the first three interviews had been coded into domains. The second point was after the core ideas had been created for each interview, and the third point was after the cross-analysis. At each point, the auditors wrote individual comments, which were discussed by the judges. If agreed on by consensus, the comments were incorporated.

The themes were based on the Swedish transcriptions and initially formulated in Swedish. The second author translated the themes into English and the first author reviewed the translations. The translations were also reviewed by a third researcher that had not been involved in the previous steps of the analysis process.

Findings

The cross-analysis of the data in the family domain resulted in the identification of four descriptive themes (see Table 2), consisting of general descriptions of the participants’ family situation in general and five themes consisting of the participants’ view on their family in relation to their delinquency (see Table 3).

Themes Concerning the Family Situation in General

Four themes concerning the participants family situation in general were identified. Quotations exemplifying each theme are presented in Table 2.

Positive and Negative Aspects of Family Relationships

This theme is based on statements describing the participants’ relationships to their families. The descriptions are multi-faceted, both within and between the participants. The narratives contain expressions of feeling well in the family and having a good relationship with parents and siblings. Such feelings and relationships are expressed, for example, as enjoying being together with the family. They also contain descriptions of negative aspects such as not receiving enough attention and feeling a lack of trust. Sometimes a development of the relationship is described, referring to how the relationship used to be, in contrast to how it is now. These are narratives of both negative and positive developments.

Physical and/or Psychological Absence of the Parents

In the data, parental absence is described both in terms of a parent that is currently present but has previously been absent and vice versa. For example, this could be a parent that had started a new family after a divorce. Some participants also describe parents that always were absent, for example, a parent living in another country. In addition to these examples of physical absence, absence is also described in terms of a lack of engagement. Independent of the kind of absence, the parent described as absent is almost exclusively the father.

Violence and Abuse Within the Family

Violent and abusive aspects of family relations are described. This theme is not a prominent part of the data, but there are statements in the interviews describing both verbal and physical violence and abuse within the families. Even if scarce, the data contain descriptions of violent conflicts between siblings and physical abuse from parents. The data also contain some examples of family members who verbally offended the participants.

Criminality and Addiction

This theme includes narratives of criminality and alcohol/substance abuse in the immediate or extended family. As with violence and abuse, this is not a prominent part of the data. The data contain narratives about ongoing substance abuse as well as abuse as part of a family member’s history.

Family and Delinquency

Five of the identified themes were based on statements specifically concerned with the participants descriptions of their families in relation to their delinquency. These themes were characterised by a higher complexity of the narratives. They were also more clearly connected to the studies overall objective—to explore family-related statements in adolescent females’ delinquency narratives from a developmental perspective.

The five themes derived from narratives concerning the family in connection to the delinquency were regarded as the main findings from the CQR-analysis. Despite describing a great variation in their general description of their families, when the family was related to the delinquency and on a higher level of abstraction, clear common denominators could be identified.

The themes consisted of statements where the participants either attributed aspects of their family relations to their criminality or by described reactions and actions from their families in connection to the crime. Quotations exemplifying each theme are presented in Table 3.

Delinquency as a Consequence of Dissatisfaction in Family Relations

This theme contains narratives in which delinquency is attributed to the quality of family relationships. These narratives constitute a prominent part of the data. Statements belonging to this theme mainly concern the parents. There are no statements of accusations against the family nor expressions of holding the family responsible for the criminal behaviour. The participants do not blame their behaviour on their family. Instead, delinquency is explained in various ways as a consequence of the quality of the family relationship. The delinquent behaviour is for example described as a way of getting attention from parents when feeling unseen or as a way of achieving autonomy. Some of the statements express an explicit idea of engaging in delinquency as a way to alter participants’ relations with the parents, for example, as a way of obtaining attention. In contrast, other statements demonstrate delinquency as the result of a wish for a higher degree of independence from the family. As an example, shoplifting or stealing is expressed as a way to attain financial freedom from the parents. Another way of attributing delinquency to family relationships is to regard the behaviour as a way of dealing with a deficit in the parental relationship. For example, one participant states that she committed crime as a way of comforting herself during a problematic family situation.

Family Reactions to Delinquency

This theme consists of the participants’ descriptions of their experiences of how their families behave in terms of reactions to the participants’ crimes. This theme does not only contain descriptions of both parental and sibling reactions. Different ways of experiencing the family as supportive and understanding are expressed in the material, but there are also descriptions of families reacting with anger when they became aware of what the adolescent had done. Another kind of reaction that is described in the statements in this theme is reactions of disappointment and parents reacting with sadness rather than anger. However, a total lack of reaction is also described. In connection to these statements, some participant reflections question whether parents reacting with indifference were bothered at all by the crime. This kind of reaction is also described as the crime making the parents withdraw and not wanting to have anything to do with the criminal behaviour of their children.

Actions Undertaken by the Family in Connection to Delinquency

This theme also contains data concerning the participants’ descriptions of their families’ behaviour, but in these themes, behaviour in terms of the actions the family undertook in connection to the crime. One kind of action the parents undertook could be regarded as actions intended to prevent the adolescent from further delinquency. This kind of action is demonstrated, for example, in statements describing parents as actively restricting and controlling the adolescent. In the interviews, the participants shared experiences of parental actions such as forcing the adolescent to take drug tests, reporting to the police when the adolescent ran away from home and forcing the adolescent to go to a psychologist. Another kind of action is providing active parental support through the legal process. For example, the participants describe how parents had followed them to the police station and accompanied them to court trials. Some statements describe being heavily questioned by the family; for example, participants’ families demanded answers about delinquent behaviour and stated the participants’ responsibility for delinquency.

Participants’ Feelings About Family Actions and Reactions

This theme is constituted by statements of the adolescents’ feelings that the participants attribute to their parents’ actions and reactions when finding out about their delinquency. The material contains expressions of feeling guilty and ashamed about the misconduct, including being embarrassed because of knowing that one had done something wrong. There are also expressions of feeling remorseful towards the parents due to a perception that the misconduct has been a burden to them. There are also statements describing the difficulty and distress of seeing one’s parents angry, sad or disappointed, for example, during a trial. Furthermore, feelings of guilt and being worried about letting the parents down are expressed. The negative feelings described in connection to the parent’s actions and reactions to the crime are, however, not described as a hindering factor for committing new crimes.

Changes in Family Relations After Delinquency

The participants express how their family relationships changed after delinquency, either directly or indirectly attributing these changes to their delinquency. These changes are both negative and positive. Examples of positive changes are a closer relationship with fewer conflicts and a greater appreciation of the family. Negative changes are mainly expressed in terms of having lost parents’ trust. However, changes are also described as an ongoing process; for example, one participant describes that she is now working to improve her relationship with her parents. In the same way, just as there are elements in the data attributing delinquency to family relational aspects, there are also statements attributing both positive and negative changes in the family relations to delinquency.

Relational Aspects of Participants’ Views of Their Families’ in Relation to Their Delinquency

The themes describing the family in relation to delinquency revealed additional patterns in terms of how the delinquency was affected by the family, and how the family was affected by the delinquency. Although not necessarily chronologically reported in the interviews, these themes could also be regarded as having different temporal positions in relation to the crime, the themes and illustrative quotes are presented in Table 4. While theme 5 (Delinquency as a consequence of dissatisfaction in the family relations) refers to what happened prior to delinquency and contains narratives of family-related factors that brought the crime about, themes 6, 7, and 8 (Family reactions to delinquency; Actions undertaken by the family in connection to delinquency; and Participants’ feelings about family actions and reactions) consist of participants’ statements concerning what happened when their delinquency ‘entered the family’. Finally, the last theme (Changes in family relations after delinquency) concerns how family relations are perceived in the aftermath of delinquent behaviour. In some cases, changes are seen as a consequence of delinquency (see Table 4).

To further investigate the relational aspects from the identified themes, the crucial points of what happened between adolescent and family were identified across both themes and participants from a developmental perspective. The key relational aspects were identified as ‘proximity’, ‘transactions’ and ‘distance’, which could be regarded as different relational positions in relation to the family (see Table 4).

Aspects of the themes of closeness or a desire for closeness (e.g., closer relationship, attention) on part of the participants or of parental actions to keep the adolescent close (e.g., support, control) were considered to convey ‘proximity’. This relational aspect included both the participants wanting their families to be closer, as well as parents being there for the participants and supporting them or keeping them close by controlling them in different ways. Aspects of the theme of the family and adolescent seeking distance from one another (e.g., independence, withdrawal, loosing trust) were regarded to convey ‘distance’. This relational aspect was expressed in terms of both the participants striving for independence and the parents distancing themselves from the crime. Finally, aspects that appeared to be expressions of some sort of emotional turbulence (e.g., conflicts, disappointment, questioning, guilt), where the families and the adolescents affected each other in various ways, were considered transactions. Sometimes these transactions could be interpreted as processes going back and forth between the parents and the participants, for example, the parents being disappointed or angry because of their children’s delinquency or the participants feeling ashamed or remorseful because of the parents’ disappointment and anger. These ‘transactions’ were regarded as having a position between proximity and distance, as this transactional process could potentially lead the relation in the direction of proximity, as well as in the direction of distance (see Table 4).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to explore family-related statements of nine Swedish adolescent females’ delinquency narratives, with an emphasis on a developmental perspective. The most prominent finding was that the families’ role in the delinquency was expressed in a way where the delinquent behaviour could be regarded as a part of the adolescent transformation of the family context. For example, expressions of the delinquency as serving the purpose of both becoming closer and more distant from the family was prominent in the data. From a developmental perspective, this could be regarded as the delinquency being a part of the ambivalence that characterizes the adolescent development of increasing autonomy while at same time, maintaining a strong sense of connection and meaningful emotional bond with parents (Barbot & Hunter, 2012). The participants are thus similar to adolescent females in general in their need for emotional closeness while at the same time desiring behavioral autonomy. The exception is that they, among other things, use delinquency to express these needs. In this view, taking part in delinquent acts can for some of the participants be viewed as part of their autonomy development (Bonnie et al., 2013).

These common denominators among the participants on a higher level of abstraction was identified despite the participants’ heterogeneity in how they described their families in general, and despite a great variation on the manifest level. Collecting the participants’ delinquency narratives unconstrained, i.e., by both collecting and coding data without presuppositions, the family appear to be central from the participants perspective. In the statements concerning family in relation to the delinquency, the family was represented in several parts of the delinquency process. This is in line with previous research where adolescent males have emphasised the role of family from their point of view (Fawole, Yusuf, & Obor, 2020; Sander et al., 2010), and adds to the literature by suggesting similar expressions from female delinquents. The participants described their family’s behaviour in connection to their delinquency, as well as attributed their delinquency to their family relations. Narratives regarding the family relations were represented in several parts of the delinquency. The families were involved in what could be regarded as the prologue of delinquency, i.e., aspects of the family before delinquency. In their narratives the participants also reported on what happened when the family had to deal with their delinquency. Finally, the family was also involved in the epilogue of delinquency, in terms of statements concerning the state of the family relations after the events related to delinquency.

In the prologue of the delinquency, the participants’ delinquent behaviour was attributed to their relation to the family. It should be noted; however, that the participants never explicitly blamed their families or regarded the family as a resource for desisting from future delinquency. This finding contrasted with the findings from our previous study focusing on peer relations (Azad et al., 2017), where peers were regarded by female offenders as the root cause for both committing and desisting from delinquency. When the family had to deal with the delinquency, the participants described the families’ actions and reactions, which included both emotional responses (e.g., getting upset or sad) as well as taking actions (e.g., making them see a psychologist, forcing them to take a drug test). These responses are similar to those expressed by parents of delinquent adolescents in response to their children’s offending (Church, MacNeil, Martin, & Nelson-Gardell, 2009). The participants also attributed their family’s actions and reactions to feelings of guilt, shame and remorse. In the narratives these feelings were however not expressed as reasons to desist from future delinquency. In the epilogue of the crime, the participants attributed changes in family relations to the delinquency. Here, the most surprising finding was that the crime was not always described as having had a negative effect on the relationship; it had in some cases instead led to a closer relationship with the family. This is noteworthy as previous studies have mainly focused on loss of trust, closer supervision and/or fewer liberties as the biggest changes in the parent–child relationships due to delinquency (e.g., Church et al., 2009).

In the delinquency narratives, the family context is, as previously mentioned, described neither as a cause of delinquency nor as a reason to desist. From a developmental perspective this content could be viewed as a notion of being close/becoming closer to or being independent/becoming more distant from the family, content that was depicted in the data across both participants and themes. Furthermore, from a developmental perspective the way the participants related to their parents in connection to delinquency could be regarded as conveying central aspects of the developmental phase they were in. During this period of life, the parent–adolescent relationship starts to be reorganised from a hierarchical structure to a more egalitarian structure (Smetana, Campione-Barr, & Metzger, 2006). As adulthood begins, the relation is fundamentally different than it was at the transition to adolescence. The aspects of the themes that were regarded to convey either proximity or distance could be interpreted as being linked to this process towards a more egalitarian relationship. However, even if adolescents orientate themselves away from the family, parents continue to be an important resource for advice and emotional support (Smetana et al., 2006). The key aspects of the themes conveying both proximity and distance, as well as participants’ views of their families’ roles in their delinquency, could also be regarded as capturing the ambiguity of this process.

In identifying the key relational aspects of the themes from a developmental perspective, themes constituted by narratives containing aspects of the families and the adolescent participants affecting each other in various ways were considered as ‘transactions’. As these transactional processes could potentially lead the relationship in the direction of proximity, as well distance, they were positioned between ‘proximity’ and ‘distance’ in the findings section. In connection to delinquency, these transactions were to a large extent characterised by negative aspects such as conflicts. However, these negative aspects do not necessarily mean that the conflict-laden transactions described in the delinquency narratives had a negative effect on the family relationships. Conflicts between parents and an adolescent can be regarded as a process through which the adolescent relationship transformation occurs, and depending on the context, these conflicts can offer benefits to psychosocial adjustment and development (Branje, 2018). Even if we do not know if that was the case in the participants’ families, we cannot exclude the possibility that delinquency-related conflicts can also serve these purposes.

The social context, of which the family naturally is an important part, is an area that is particularly subject to change (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). For example, Kubrin, Stucky, & Krohn (2008) posit that during adolescence there is a movement from restricted (e.g., family) to unrestricted environment (e.g., peers). The social context is also a part of the adolescent’s life that has been theoretically central, for example, in Erikson’s (1980) psychosocial theory of development, where adolescent identity development is defined as a process of the interactions between person and context (Kroger, 2004). The need for conceptualising identity formation as a process of the interactions or transactions between the person and context has also been stressed by other authors (e.g., Bosma & Kunnen, 2001; Kroger, 2004). From this perspective, the balance between the self and those the adolescent is surrounded by is what conceptualises identity in adolescence (Kroger, 2004), which might be a way of understanding the role of both peers and family in relation to delinquency. In comparison to for example Moffitt’s (1993) theory, suggesting that delinquency limited to adolescence is a way of achieving autonomy, the developmental perspective offers a more complex picture that also capture the ambiguity of this developmental phase. Furthermore, viewing adolescent limited delinquency in terms of adolescent development can contribute with dynamic and more nuances to the transactional family system.

Implications

The rehabilitation of young offenders tends to focus on the delinquent behaviour and its causes (e.g., Andrew & Bontana, 2010). Our findings suggest that for females with limited delinquency, a potential option could be to explore the role that delinquency plays in the adolescent family context. A constructive way of understanding limited delinquency, both in research and practice, might be to view this behaviour as an ingredient of the adolescent transformation of the family context. This could mean to consider delinquency as serving the purpose of becoming closer to as well as more distant from each other within the family context. It could also be meaningful to consider that the transactions between family members in connection to the crime, even if problematic, could be regarded as fairly normal for this developmental phase. Providing both the adolescents and their families with a developmental perspective as a tool for understanding the delinquent behaviour might be a helpful way of making sense of a behaviour, likely to cause distress and conflicts within the family context, which is of fundamental importance for the adolescents’ continuous development.

These findings, together with our previous findings (Azad et al., 2017), also highlights the importance of support in finding pro-social contexts, behaviours and resources that meet the needs of expressing the adolescents’ increasing independence (Farrell, Thompson, & Mehari, 2017).

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has intentionally exclusively focused on the developmental aspects of adolescence. Exclusive focus on one perspective naturally excludes other perspectives and the alternative explanations these would lead to. Our findings must therefore be regarded as one out of many possible ways of understanding this field of research.

We consider the small-sample size as the main limitation of this study. The findings from this study should therefore mainly be regarded as potential entry points for future research. It is likely that the female offenders who agreed to participate differed substantially from those who did not. Recruiting participants from two larger cities, compared to smaller municipalities, might also have had an impact on the findings. The interviews were open and did not specifically focus on family factors but rather asked general questions about the participants’ views on their delinquency. The findings could have been different if the focus had been explicitly on family factors. However, the spontaneous focus on the family, unguided by the interviewer, can also be regarded as a strength, as the spontaneous reports on the families’ roles show that the participants viewed their families as central in relation to their delinquency.

Furthermore, we consider applying the perspective of normative adolescent development on this group of offenders as one of the strengths of this study. Our findings indicate that the developmental perspective on the family factor for females with limited delinquency is a meaningful way to further investigate this group of offenders. In particular, this perspective might enable to capture the ambiguity that characterizes the emancipatory process of adolescence. To further explore the family factor from the perspective of adolescent development could in the long-term also potentially contribute to the design of meaningful community-based measures for this yet under-researched group of young offenders.

References

Andersson, F., Levander, S., Svensson, R., & Torstensson Levander, M. (2012). Sex differences in offending trajectories in a Swedish cohort. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 22, 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.1822.

Andersson, F., Levander, S., & Torstensson Levander, M. T. (2013). A life-course perspective on girls’ criminality. In A.-K. Andershed (Ed.), Girls at risk (pp. 119–137). New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4130-4_7.

Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2010). Rehabilitating criminal justice policy and practice. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 16(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018362.

Azad, A., & Ginner Hau, H. (2018). Adolescent females with limited delinquency: At risk of school failure. Children and Youth Services Review, 95, 384–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.11.015.

Azad, A., & Ginner Hau, H. (2020). Adolescent females with limited delinquency: A follow up on educational attainment and recidivism. Child & Youth Care Forum, 49(2), 325–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-019-09530-8.

Azad, A., Ginner Hau, H., & Karlsson, M. (2017). Adolescent female offenders’ subjective experiences of how peers influence norm-breaking behaviour. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 35(3), 257–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-017-0526-0.

Barbot, B., & Hunter, S. R. (2012). Developmental changes in adolescence and risks for delinquency. In E. L. Grigorenko (Ed.), Handbook of juvenile forensic psychology and psychiatry. Boston: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0905-2_2.

Bonnie, R. J., Johnson, R. L., Chemers, B. M., & Schuck, J. A. (2013). Reforming juvenile justice: A developmental approach. Washington: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/14685.

Bosma, H. A., & Kunnen, E. S. (2001). Determinants and mechanisms in ego identity development: A review and synthesis. Developmental Review, 21(1), 39–66. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.2000.0514.

Branje, S. (2018). Development of parent–adolescent relationships: Conflict interactions as a mechanism of change. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 171–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12278.

Church, W. T., MacNeil, G., Martin, S. S., & Nelson-Gardell, D. (2009). What do you mean my child is in custody? A qualitative study of parental response to the detention of their child. Journal of Family Social Work, 12(1), 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10522150802654286.

Diamond, G. M., Shilo, G., Jurgensen, E., D’Aguelli, A., Samarova, V., & White, K. (2011). How depressed and suicidal sexual minority adolescents understand the causes of their distress. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health, 15(2), 130–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2010.532668.

Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the life cycle. New York, NY: Norton.

Estrada, F., & Flyghed, J. (2017). Den svenska ungdomsbrottsligheten [The Swedish juvenile delinquency]. Studentlitteratur AB.

Farrell, A. D., Thompson, E. L., & Mehari, K. R. (2017). Dimensions of peer influences and their relationship to adolescents’ aggression, other problem behaviours and prosocial behaviour. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(6), 1351–1369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0601-4.

Fawole, A. O., Yusuf, M. S., & Obor, D. O. (2020). Could my home be responsible for this? Adolescents’ reports on family situations and delinquency in Iwo, Osun State, Nigeria. Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology, 17(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.36108/njsa/6102/14(0270).

Gaarder, E., & Belknap, J. (2004). Little women: Girls in adult prison. Women & Criminal Justice, 15(2), 51–80. https://doi.org/10.1300/J012v15n02_03.

Ginner Hau, H. (2010). Swedish young offenders in community based rehabilitative programmes: Patterns of antisocial behaviour, mental health and recidivism (Doctoral dissertation). Department of Psychology, Stockholm University. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00792.x.

Ginner Hau, H., & Smedler, A.-C. (2011a). Different problems: same treatment. Swedish juvenile offenders in community-based rehabilitative programmes. International Journal of Social Welfare, 20(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2009.00697.

Ginner Hau, H., & Smedler, A. (2011b). Young male offenders in community-based rehabilitative programmes: Self-reported history of antisocial behaviour predicts recidivism. International Journal of Social Welfare, 20(4), 413–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00792.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Herrman, J. W., & Silverstein, J. (2012). Girls’ perceptions of violence and prevention. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 29(2), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370016.2012.670569.

Hill, C. E. (2012). Consensual qualitative research: A practical resource for investigating social science phenomena. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Hill, C. E., Knox, S., Thompson, B. J., Williams, E. N., Hess, S. A., & Ladany, N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196.

Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., & Williams, E. N. (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. The Counseling Psychologist, 25(4), 517–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000097254001.

Hoeve, M., Dubas, J. S., Eichelsheim, V. I., Van Der Laan, P. H., Smeenk, W., & Gerris, J. R. (2009). The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(6), 749–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8.

Kang, T. (2019). The transition to adulthood of contemporary delinquent adolescents. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 5(2), 176–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-019-00115-6.

Keijsers, L. (2016). Parental monitoring and adolescent problem behaviours: How much do we really know? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40(3), 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415592515.

Keijsers, L., & Poulin, F. (2013). Developmental changes in parent–child communication throughout adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 49(12), 2301–2308. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032217.

Kerig, P. K., & Schulz, M. S. (2012). Introduction to the volume the transition from adolescence to adulthood. In P. K. Kerig, M. S. Schulz, & S. T. Hauser (Eds.), Adolescence and beyond: Family processes and development (pp. 3–12). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2003). Parenting of adolescents: Action or reaction? In A. C. Crouter & A. Booth (Eds.), Children’s influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships (pp. 121–151). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kerr, M., Stattin, H., & Burk, W. (2010). A reinterpretation of parental monitoring in longitudial perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 39–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00623.

Kroger, J. (2004). Identity in adolescence: The balance between self and other (3rd ed.). Hove, UK: Routledge.

Kroneman, L. M., Loeber, R., Hipwell, A. E., & Koot, H. M. (2009). Girls’ disruptive behaviour and its relationship to family functioning: A review. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18(3), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-008-9226-x.

Kruttschnitt, C., & Giordano, P. (2009). Family influences on girls’ delinquency. In M. A. Zahn (Ed.), The delinquent girl (pp. 107–126). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Kubrin, C. E., Stucky, T. D., & Krohn, M. D. (2008). Researching theories of crime and deviance. New York: Oxford University Press.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2001). Understanding desistance from crime. Crime and Justice, 28, 1–69. https://doi.org/10.1086/652208.

Massoglia, M., & Uggen, C. (2010). Settling down and aging out: Toward an interactionist theory of desistance and the transition to adulthood. American Journal of Sociology, 116(2), 543–582. https://doi.org/10.1086/653835.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behaviour: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.100.4.674.

Moffitt, T. E. (2001). Sex differences in antisocial behaviour: Conduct disorder, delinquency, and violence in the Dunedin longitudinal study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moffitt, T. E. (2006). A review of research on the taxonomy of life-course-persistent versus adolescence-limited antisocial behaviour. In F. T. Cullen, J. P. Wright, & K. R. Blevins (Eds.), Taking stock: The status of criminological theory (pp. 277–311). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Nilsson, A., & Estrada, F. (2009). Kriminalitet och livschanser. Uppväxtvillkor, brottslighet och levnadsförhållanden som vuxen [Criminality and life prospects. Childhood conditions, crime and living conditions in adults age]. Arbetsrapport 2009:20. Stockholm: Institute for Future Studies.

Odgers, C. L., Moffitt, T. E., Broadbent, J. M., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., … & Caspi, A. (2008). Female and male *****antisocial trajectories: From childhood origins to adult outcomes. Development and Psychopathology, 20(2), 673–716. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579408000333

Pardini, D. A., Waller, R., & Hawes, S. W. (2015). Familial influences on the development of serious conduct problems and delinquency. In J. Morizot & L. Kazemina (Eds.), The development of criminal and antisocial behaviour (pp. 201–220). Cham: Springer.

Patterson, G. R., & Yoerger, K. (2002). A developmental model for early- and late-onset delinquency. In J. B. Ried, G. R. Patterson, & J. J. Shyder (Eds.), Antisocial behaviour in children and adults: A developmental analysis and the Oregon model for intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10468-007.

Peterson, G. W. (2005). Family influences on adolescent development. In T. P. Gullotta & G. R. Adams (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent behavioral problems (pp. 27–55). US: Springer.

Piquero, A. R., Diamond, B., Jennings, W. G., & Reingle, J. M. (2013). Adolescence-limited offending. In C. L. Gibson & M. D. Krohn (Eds.), Handbook of life-course criminology: Emerging trends and directions for future research (pp. 129–142). New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5113-6_8.

Roisman, G. I., Monahan, K. C., Campbell, S. B., Steinberg, L., & Cauffman, E. (2010). Is adolescence-onset antisocial behaviour developmentally normative? Development and Psychopathology, 22(2), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579410000076.

Sander, J. B., Sharkey, J. D., Olivarri, R., Tanigawa, D. A., & Mauseth, T. (2010). A qualitative study of juvenile offenders, student engagement, and interpersonal relationships: Implications for research directions and preventionist approaches. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 20(4), 288–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2010.522878.

Smetana, J. G., Campione-Barr, N., & Metzger, A. (2006). Adolescent development in interpersonal and societal contexts. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 255–284. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190124.

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71(4), 1072–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00210.

Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. S. (2001). Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 83–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83.

Steinberg, L., & Silk, J. S. (2002). Parenting adolescents. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (Vol. 1, pp. 103–133)., Children and parenting Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Swedish Government. (2006). Ingripanden mot unga lagöverträdare. [Interventions against young offenders]. Proposition 2005/06:165.

Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. (2019). Straffrättsliga reaktioner på ungas brott 2010–2016. [Legal reactions on young person’s crimes 2010-2016]. Stockholm: Brottsförebyggande rådet (Brå).

Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. (2020). Kriminalstatistik 2019. Personer lagförda för brott. Slutlig statistik. [Crime statistics 2019. Persons prosecuted for crimes. Final statistics.]. Stockholm: Brottsförebyggande rådet (Brå).

Walters, G. D. (2019). Mothers and fathers, sons and daughters: Parental knowledge and quality of the parent-child relationship as predictors of delinquency in same-and cross–sex parent-child dyads. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(7), 1850–1861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01409-5.

Wester, K. L., MacDonald, C. A., & Lewis, T. F. (2008). A glimpse into the lives of nine youths in a correctional facility: Insight into theories of delinquency. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 28(2), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1874.2008.tb00036.x.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by grants from the Children’s House Foundation (Grant No. FOA12-0050) and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (Grant No. 2011-1208), both to Hanna Ginner Hau. We are very grateful to the participants for sharing their stories with us, as well as the social workers for helping us with the recruitment. Finally, we thank Markus Karlsson, Stephan Hau and Sigríður Sigurjónsdóttir, for their contributions in the process of analysing the data.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The present study was approved by the Stockholm Regional Ethics Board (2012/1259-31).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ginner Hau, H., Azad, A. Swedish Adolescent Female Offenders with Limited Delinquency: Exploring Family-Related Narratives from a Developmental Perspective. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 39, 219–232 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00719-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00719-8