Abstract

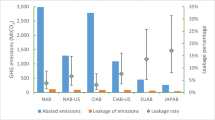

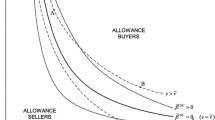

We contribute to the growing literature on how political support for domestic policies that contribute to global collective goods is impacted by other countries’ policy actions. To do so, we focus on carbon taxation, one of the most important yet contested policy instruments for mitigating global warming, in the world’s third largest economy, Japan. Using a combination of two experiments embedded in a representative public opinion survey, we examine arguments relating to how the adoption and level of ambition of other countries’ carbon taxes affect the public’s preferences for current and future carbon tax designs. We find evidence that the choices of other countries affect both support for carbon taxation and preferences over its design. More ambitious carbon pricing in other countries increases support for carbon taxation, while less ambitious pricing reduces support. Moreover, information about lower carbon prices in other countries decreases support more than other countries having no carbon taxation at all. Public support for more stringent domestic carbon pricing thus hinges on the policy choices of other countries, contrary to other environmental issues. Our research also shows, however, that particular domestic policy design choices can help in mitigating otherwise negative effects of non-cooperative behavior by other countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

https://unfccc.int/about-us/regional-collaboration-centres/the-ci-aca-initiative/about-carbon-pricing#eq-6 (last accessed on December 17, 2020)

https://www.env.go.jp/press/files/en/868.pdf (last accessed on April 27, 2021)

http://www.globalcarbonatlas.org/en/CO2-emissions (last accessed on April 27, 2021)

https://www.env.go.jp/en/earth/cc/2030indc.html (last accessed on December 26, 2019)

https://www.kikonet.org/info/press-release/2015-04-30/2030-climate-target (last accessed on December 26, 2019)

https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/japan/ (last accessed on December 26, 2019)

https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/strategies/2030_en (last accessed on December 26, 2019)

https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/japan/ (last accessed on December 26, 2019)

Other industrialized countries’ carbon tax rates are in fact much higher, including those in Sweden (1991, US$127), Switzerland (2008, US$96), Finland (1990, US$60–70), Norway (1991, US$3–59), France (2014, US$50), Iceland (2010, US$31), Denmark (1992, US$26), Ireland (2010, US$22), Slovenia (1996, US$19), Spain (2014, US$17), Portugal (2015, US$14), Latvia (2004, US$5), Chile (2017, US$5), Singapore (2019, US$4), and Estonia (2000, US$4) (World Bank 2019, 25-26). Information in parentheses shows the year of introduction and tax rates as of 2019 (World Bank 2019).

Countries with very low carbon taxes include Poland, Ukraine, Estonia, and Mexico.

Shortly before the introduction of the carbon tax, Keidanren called on the government to rethink the new tax because it raises energy costs further and might push companies to move operations to countries that regulate carbon emissions less. (https://www.reuters.com/article/us-energy-japan-tax/japans-new-carbon-tax-to-cost-utilities-1billion-annually-idUSBRE8990G520121010, last accessed on December 26, 2019).

https://country-level-scc.github.io/explorer/ (last accessed on December 26, 2019)

Likewise, policy diffusion studies analyze policy interaction among countries. However, they address the effect of a country’s policy “adoption” on other countries rather than the effect of its policy “level,” the latter of which is our main analytical focus. While diffusion studies suggest that geographically or socially similar or proximate countries have greater policy influences, we do not distinguish proximities of countries to avoid the complexity of our survey design.

The carbon price of 3 USD/tCO2 (from World Bank carbon price 2018) was converted into yen (340 yen/tCO2). Then, this was multiplied by Japan’s CO2 emissions per capita (9.5 tCO2) to calculate monthly carbon tax costs per person.

We conducted manipulation checks to make sure respondents understood each frame correctly. Details on manipulation checks are presented in A.2. in the Appendix.

As before, we present the conjoint results from the forced choices, but the main results hold with rating choices, which are presented in A.8. in the Appendix.

References

Abreu D (1988) On the theory of infinitely repeated games with discounting. Econometrica 56(2):383–396

Anderson B et al (2017) Public opinion and environmental policy output: a cross-national analysis of energy policies in Europe. Environ Res Lett 12:114011

Axelrod RM, Hamilton WD (1984) The evolution of cooperation. Basic Books, New York

Axelrod R, Keohane RO (1986) Achieving cooperation under an-archy: strategies and institutions. In: Oye K-n (ed) Cooperation under Anarchy. Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp 226–254

Bansak K, Hainmueller J, Hopkins D, Yamamoto T (2019) Beyond the breaking point? Survey satisficing in conjoint experiments. Polit Sci Res Methods:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.13

Barrett S (2003) Environment and statecraft: the strategy of environmental treaty-making: the strategy of environmental treaty-making. OUP Oxford, Oxford

Barrett S (2016) Coordination vs. voluntarism and enforcement in sustaining international environmental cooperation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113(51):14515–14522

Bechtel MM, Scheve KF (2013) Mass support for global climate agreements depends on institutional design. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110(34):13763–13768

Beiser-McGrath LF, Bernauer T (2019a) Commitment failures are unlikely to undermine public support for the Paris Agreement. Nat Clim Chang 9(3):248

Beiser-McGrath LF, Bernauer T (2019b) Could revenue recycling make effective carbon taxation politically feasible? Sci Adv 5(9):eaax3323

Bergquist P, Mildenberger M, Stokes L (2020) Combining climate, economic, and social policy builds public support for climate action in the US. Enviromental Research Letters 15(5):054019

Bernauer T, Gampfer R (2015) How robust is public support for unilateral climate policy? Environ Sci Pol 54:316–330

Bernauer T, Dong L, McGrath LF, Shaymerdenova I, Zhang H (2016) Unilateral or reciprocal climate policy? Experimental evidence from China. Politics Gov 4(3):152–171

Böhmelt T (2020) Environmental disasters and public-opinion formation: a natural experiment. Environ Res Commun 2(8):081002

Böhringer C, Rutherford TF (1997) Carbon taxes with exemptions in an open economy: a general equilibrium analysis of the German tax initiative. J Environ Econ Manag 32(2):189–203

Bristow G (2019) Yellow fever: populist pangs in France: reflections on the gilets jaunes movement and the nature of its populism. Soundings 72(72):65–78

Burstein P (2003) The impact of public opinion on public policy: a review and an agenda. Polit Res Q 56(1):29–40

Cabinet Office (2007) Questionnaire survey on measures for global warming control, (in Japanese). https://survey.gov-online.go.jp/h17/h17-globalwarming/2-4.html. Accessed 28 June 2021

Carattini S, Carvalho M, Fankhauser S (2018) Overcoming public resistance to carbon taxes. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 9(5):e531

Chan G, Stavins R, Ji Z (2018) International climate change policy. Ann Rev Resour Econ 10:335–360

Davenport C (2016) Carbon pricing becomes a cause for the World Bank and IMF. The New York Times

Davidovic D, Harring N, Jagers SC (2020) The contingent effects of environmental concern and ideology: institutional context and people’s willingness to pay environmental taxes. Environ Polit 29(4):674–696

Dolšak N, Adolph C, Prakash A (2020) Policy design and public support for carbon tax: evidence from a 2018 US national online survey experiment. Public Adm 98(4):905–921

Douenne T, Fabre A (2020) French attitudes on climate change, carbon taxation and other climate policies. Ecol Econ 169:106496

Fairbrother M (2019) When will people pay to pollute? Environmental taxes, political trust and experimental evidence from Britain. Br J Polit Sci 49(2):661–682

Fesenfeld LP, Wicki M, Sun Y, Bernauer T (2020) Policy packaging can make food system transformation feasible. Nat Food 1(3):173–182

Fischer C, Fox AK (2012) Comparing policies to combat emissions leakage: border carbon adjustments versus rebates. J Environ Econ Manag 64(2):199–216

Gilardi F, Wasserfallen F (2019) The politics of policy diffusion. Eur J Polit Res 58(4):1245–1256

Goldstein JS, Pevehouse JC (1997) Reciprocity, bullying, and international cooperation: time-series analysis of the Bosnia conflict. Am Polit Sci Rev 91(3):515–529

Grieco JM (1988) Realist theory and the problem of international cooperation: analysis with an amended prisoner's dilemma model. J Polit 50(3):600–624

Guilluy C (2018) France is deeply fractured. Gilets jaunes are just a symptom. The Guardian, December, 2, 2018

Hainmueller J, Hopkins DJ, Yamamoto T (2014) Causal inference in conjoint analysis: understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Polit Anal 22(1):1–30

Hovi J, Sprinz DF (2006) The limits of the law of the least ambitious program. Glob Environ Polit 6(3):28–42

Jagers SC, Hammar H (2009) Environmental taxation for good and for bad: the efficiency and legitimacy of Sweden's carbon tax. Environ Polit 18(2):218–237

Keohane RO (1986) Reciprocity in international relations. Int Organ 40(1):1–27

Klenert D, Mattauch L, Combet E, Edenhofer O, Hepburn C, Rafaty R, Stern N (2018) Making carbon pricing work for citizens. Nat Clim Chang 8(8):669–677

Latré E, Perko T, Thijssen P (2017) Public opinion change after the Fukushima nuclear accident: the role of national context revisited. Energy Policy 104:124–133

Leeper TJ, Hobolt SB, Tilley J (2020) Measuring subgroup preferences in conjoint experiments. Political Analysis 28(2):207-221

Lockwood B, Whalley J (2010) Carbon-motivated border tax adjustments: old wine in green bottles? World Econ 33(6):810–819

McGrath LF, Bernauer T (2017) How strong is public support for unilateral climate policy and what drives it? Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 8(6):e484

Mildenberger M (2019) Support for climate unilateralism. Nat Clim Chang 9(3):187–188

Oye KA (1986) Cooperation under anarchy. Princeton Universi-ty Press, Princeton

Poortinga W, Aoyagi M, Pidgeon NF (2013) Public perceptions of climate change and energy futures before and after the Fukushima accident: a comparison between Britain and Japan. Energy Policy 62:1204–1211

Rhodes C (1989) Reciprocity in trade: the utility of a bargaining strategy. Int Organ 43(2):273–299

Ricke K, Drouet L, Caldeira K, Tavoni M (2018) Country-level social cost of carbon. Nat Clim Chang 8(10):895

Rudolph S (2018) Carbon pricing in Japan and the prospects for northeast Asia carbon market linking. Carbon Market Cooperation in Northeast Asia: assessing Challenges and Overcoming Barriers 94–102

Sandler T (1997) Global challenges: an approach to environmental, political, and economic problems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Stadelmann-Steffen I, Dermont C (2018) The unpopularity of incentive-based instruments: what improves the cost–benefit ratio? Public Choice 175(1-2):37–62

Stadelmann-Steffen I, Dermont C (2020) Citizens’ opinions about basic income proposals compared–A conjoint analysis of Finland and Switzerland. J Soc Policy 49(2):383–403

Tingley D, Tomz M (2014) Conditional cooperation and climate change. Comp Pol Stud 47(3):344–368

Tingley D, Tomz M (2020) International commitments and domestic opinion: the effect of the Paris Agreement on public support for policies to address climate change. Environ Polit 29(7):1135–1156

Uji A, Prakash A, Song J (2021) Does the “NIMBY syndrome” undermine public support for nuclear power in Japan? Energy Policy 148:111944

Underdal A (1998) Explaining compliance and defection: three models. Eur J Int Relat 4(1):5–30

Wicki M, Fesenfeld L, Bernauer T (2019) In search of politically feasible policy-packages for sustainable passenger transport: insights from choice experiments in China, Germany, and the USA. Environ Res Lett 14(8):084048

World Bank (2019) State and trends of carbon pricing 2019 (English). World Bank Group, Washington, D.C. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/191801559846379845/State-and-Trends-of-Carbon-Pricing-2019. Accessed 28 June 2021

Jagers SC, Martinsson J, Matti S (2019) The impact of compensatory measures on public support for carbon taxation: An experimental study in Sweden. Climate Policy 19(2);147-160

Bernauer T (1995) The effect of international environmental institutions: how we might learn more. International Organization 351-377

Acknowledgements

We thank Patrick Bayer, Lukas Fesenfeld, Dennis Kolcava, Vally Koubi, Matto Mildenberger, Michael Tomz, and two anonymous reviewers for very valuable comments. This research was made possible by generous funding from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (#18H03623).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author ordering is alphabetical, reflecting the authors’ equal contribution. LFB-M, TB, JS, and AU jointly designed the study. JS and AU collected the data. JS analyzed the data. LFB-M, TB, and AU wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Kobe University approved the survey experiment described in this article. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 6222 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beiser-McGrath, L.F., Bernauer, T., Song, J. et al. Understanding public support for domestic contributions to global collective goods. Climatic Change 166, 51 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03137-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03137-6